Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (born January 11, 1757 or 1755 in Nevis , West Indies , today St. Kitts and Nevis , † July 12, 1804 in New York City ) was an American statesman, one of the founding fathers of the United States and its first Treasury Secretary . He is also considered to be one of the first state theorists of representative democracy and the American school of economics.

Hamilton was born an illegitimate child in St. Kitts and Nevis. With a scholarship from business leaders and the governor of St. Croix , where Hamilton was living at the time, he was able to study in New York at King's College, later Columbia University . After the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War , Hamilton joined the military company Hearts of Oak , where he was quickly promoted to captain . George Washington noticed him and appointed him his aide-de-camp , as which he excelled. Desiring to find glory on the battlefield, he resigned from this position to take command of the Battle of Yorktown , in which his wish was granted.

He married Elizabeth Schuyler , the daughter of General Philip Schuyler . After the War of Independence he became a lawyer and was a member of the Continental Congress from 1782 to 1783 . In the Constitutional Convention of the United States , he advocated the election of the president and senators for life and wanted to establish a strong central government - vis-à-vis the individual states. Hamilton only partially prevailed with the latter requirement. In the Federalist Papers, he promoted and defended the United States Constitution with John Jay and James Madison .

In the Washington cabinet he was Treasury Secretary from 1789 to 1795. In this post he proposed in several reports to Congress financial reforms that contributed significantly to the development of the economy of the young United States. He initiated the founding of the First Bank of the United States in 1790 and thus created the basis for today's Federal Reserve System . He preferred industry and trade, with which he made no friends in the agrarian southern states . Around 1792 the Federalist Party was formed around him , the opposing party to the Democratic-Republican Party of Thomas Jefferson , his greatest political opponent. Even after his resignation on January 31, 1795, Hamilton remained an important politician, but his criticism of the federalist candidate John Adams during the presidential election in 1800 heralded his political end. Hamilton died on July 12, 1804 of an injury sustained the previous day from a duel with his longtime political rival, incumbent Vice President Aaron Burr .

In 1780 he was elected to the American Philosophical Society and in 1791 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . Hamilton's portrait is on the $ 10 banknote.

Life

Early life (1755 / 1757–1775)

Little is known about Hamilton's early life, as Hamilton himself reported little of his early life to his own family. In the books The Life of Alexander Hamilton (1840) and Life of Alexander Hamilton: A History of the Republic of the United States of America (7 volumes, 1857–1864) by Hamilton's son John Church Hamilton , this collected his knowledge about his father. However, his reports are often questioned. Remaining knowledge of Hamilton's youth comes from administrative records in the Caribbean, where Hamilton grew up. The most important research in this area was carried out from 1901 by HU Ramsing and Gertrude Atherton . Ramsing's research was published in Personal-Historik Tiddskrift in 1939 , while Atherton used her findings for her novel The Conqueror (1902). Major discoveries include the identities of Hamilton's mother and his maternal grandparents. The historian Harold Larson found further documents in the archives of the Virgin Islands . He used this together with the research of Ramsing for an article in the William and Mary Quarterly . More is known about Hamilton's studies from the notes of his friends Hercules Mulligan and Robert Troup , but their “narratives” differ in several important details.

parents house

On the maternal side, Hamilton is descended from Huguenots who fled France to the island of Nevis as a result of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV . On his father's side, he comes from the Scottish clan Hamilton . The relationship between his parents Rachael Faucett (several other spellings are also possible; often Anglicized Fawcett) and James Hamilton was illegitimate, which his political opponents ridiculed even after his death. To this day, famous is John Adams description of Hamilton as " bastard brat of a Scottish trader" ( English bastard brat of a Scotch Pedler ).

It was also alleged that his mother, and thus he too, were partly black. The famous black scholar WEB Du Bois Hamilton called "our" and the African-American abolitionist William Hamilton (1773-1836) claimed to be his son. The Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow commissioned the geneticist Gordon Hamilton, who tested the DNA of the Hamilton family, to also test the descendants of Alexander Hamilton. At the time of the publication of his biography, the results were not yet known. In an interview from 2016 with the interviewer Brian Lamb on the broadcaster C-SPAN , he announced that the test was inconclusive, but Hamilton's skin color in portraits would indicate Scottish ancestry.

Childhood and adolescence

Historians consider the date of birth January 11th to be certain, but there are still discussions about the year of birth to this day. Hamilton himself almost always stated 1757 - possibly in order not to be rejected from college because of his age, which was already advanced for his contemporaries. In contrast, several Caribbean documents indicate the year of birth 1755.

In January 1766, James Hamilton left his family, for which the motivation is still unknown. Alexander Hamilton, who later exchanged letters with his father, suspected that his father could no longer support his family. A symbolic end to Hamilton's childhood was the death of his mother, who fell ill with a fever to which she succumbed on February 19, 1768. Alexander also fell ill, but was able to recover until his mother's funeral. The half-orphans were placed in the care of their cousin Peter Lytton, who only committed suicide a year later because of the death of his wife. Neither his possessions, nor those of Peter Lytton's father, who also died, nor those of Rachel Faucett went to Alexander or his brother. Eventually Hamilton was taken in by the eminent merchant Thomas Stevens, whose son Edward Stevens was his friend. Since this also looked similar to Hamilton, there were several rumors of a possible paternity of Thomas Stevens.

Between 1766 and 1767 he began to work for the company Beekman and Cruger on St. Croix in Christiansted . This company was run by New Yorkers Nicholas Cruger and Beekman, who were members of major merchant families. Hamilton soon showed himself to be a talented administrator. In addition to Hamilton's knowledge of French, the Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow particularly values Hamilton's hard work, his independence and his ambition as his most important qualities in working for Cruger. His employers were also convinced of Hamilton's talent; when Cruger spent five months in New York in 1771, he put Hamilton in charge of the company. It seems that he excelled at this task. His work under Beekman and Cruger gave him valuable administrative and commercial experience which he benefited from while serving as Treasury Secretary. Hamilton himself called it the most important part of his education, and Hamilton biographer Jacob Ernest Cooke compared it to a modern college degree.

Hamilton was probably only receiving private tuition, possibly from a Jew or his own mother. But this lesson does not seem to have been particularly profound; much of Hamilton's education probably came from reading his mother's 34 books. These probably included a French translation of Niccolò Machiavelli's Der Fürst , Plutarch's parallel biographies , and especially the poems of Alexander Pope . Hamilton's pastimes included writing poems published in the Royal Danish American Gazette . Initially they were about love, but Hamilton soon switched his focus to religion. It can be assumed that the Presbyterian priest Hugh Knox, a friend of Hamilton, influenced this change. Hamilton also wrote many letters in his childhood. The oldest surviving letter was addressed to Edward Stevens, who studied medicine at Kings College (now Columbia University ), and was written on November 11, 1769. Hamilton described displeasure with his low social status and the desire for a war in which he could prove himself.

On October 31, a hurricane devastated St. Croix Island, which Hamilton described in a letter to his father. Presumably at the behest of Knox, this letter was published in the Royal Danish American Gazette on October 3rd . According to Chernow, there were two reasons the letter amazed readers: Hamilton's relatively young age and low social status, and the description of the hurricane as a punishment from God. The letter is said to have convinced the island's upper class of Hamilton's talent, which is why they financed a scholarship to study in the Thirteen Colonies . The main donors were arguably his employers, his cousins Ann Lytton Venton and Thomas Stevens. It is believed that Hamilton boarded a ship to Boston as early as October , but poems published in the Royal Danish American Gazette after October 1772 point to a voyage after the winter of 1772/1773. Several historians such as B. Jacob Ernest Cooke criticize the portrayal of the letter as the trigger for the scholarship as unrealistic.

studies

After landing in Boston by ship, Hamilton traveled overland to New York City , where he received part of his scholarship from Kortright and Company. There his only contact was Edward Stevens, but he was able to establish many contacts with later leaders of the independence movement and colonial elites. He was known to the most important Presbyterian churchmen in New York, John Rodgers and John M. Mason, through letters of recommendation from Knox . The political elite, with whom he became friends through Knox's letters of recommendation, included William Livingston , the first governor of New Jersey during the American Revolution, and Elias Boudinot , later president of the Continental Congress and representative . Visitors to Elizabeth Town , where Hamilton attended the Elizabethtown Academy , included William Alexander, Lord Stirling , later Major General in the American Army during the Revolution, John Jay , later Secretary of State during the Continental Congress, Chief Justice and Governor of New York, and William Duer , later a major speculator. Hamilton also made connections with the more radical part of society with Sons of Liberty member Hercules Mulligan. Like most colonial elites on the road to the American Revolutionary War , Hamilton supported a settlement with the British crown.

Hamilton first enrolled at the Elizabethtown Preparatory Academy to study Latin, Greek, and advanced mathematics, which were compulsory for college entry. After graduating from Elizabethtown Academy with impressive results, he had to choose one of the nine colleges of the Thirteen Colonies. An obvious choice was Princeton University , where Boudinot and Livingston were members of the Board of Trustees . Under the leadership of John Witherspoon , Princeton also developed into a Whigs and Presbyterian university , which, after Mulligan, was the determining factor for Hamilton. Hamilton made an application for admission there with the request to be allowed to complete accelerated studies, but this was refused, which is why Hamilton had to choose another college. His new choice was Kings College in New York, which, under the leadership of Myles Cooper , became one of the strongholds of the Tories and the British colonial power together with the city of New York . Hamilton probably joined Kings College in the winter of 1773/74. He was allowed private tuition with professors to get a degree more quickly; so the professor Robert Harpur taught him in September 1774 in mathematics. The Scot Harpur probably also told him about the Scottish Enlightenment , which was promoted by Adam Smith and David Hume and which strongly influenced Hamilton's economic ideas. Other Enlightenment figures such as Montesquieu were also part of Hamilton's reading, but Hamilton initially studied for a degree in medicine. He later switched to law studies.

In a college debating club, including with Troup and Nicholas Fish , he first represented a position loyal to the king, according to Troups, but he soon became an advocate of independence from the colonial power and used the club to revise his later anti-British essays . Troup also reports that the Boston Tea Party was a key factor in the change of opinion. After Paul Revere reported it in New York, Hamilton is said to have traveled directly to Boston to write a report that supported the Tea Party. Chernow suspects that this was the anonymously published Defense and Destruction of the Tea in the New York Journal . According to the so-called " Intolerable Acts ", in which the British Parliament harshly punished the colonies for the Boston Tea Party in the opinion of the colonists, public opinion turned against the colonial power even in the Tory stronghold of New York. In response to them, the colonies rallied in the Continental Congress , where counter-actions were to be decided. While radicals sought a boycott of British goods, moderates saw a boycott as too provocative. The radical Sons of Liberty gathered in the open fields outside New York, where, according to his son's biographies, Hamilton gave a moving speech that supported the Boston Tea Party and established him in the movement. However, apart from the biography of John Church Hamilton, there is no other source material about this speech, which is why it is doubted by some historians. The actions of the Continental Congress, which opted for a complete embargo against the British colonial power, shocked many Tories and especially the clergy of the colonies. For example, the episcopal Samuel Seabury wrote under the pseudonym "A Westchester Farmer" loyalist essays against the Continental Congress. Hamilton responded to his essay under the pseudonym "A Friend to America" in the sensational articles A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress (published December 15, 1774) and The Farmer Refuted (published January 23, 1775), in which he According to Chernow, he first showed his talent as a writer. The two anonymous writings also show that Hamilton had become thoroughly familiar with the political and economic problems of the colonies in the year that had passed since his arrival in Boston. Cooke, on the other hand, criticizes the fact that Hamilton often resorted to arguments from other Whigs and that his style was not yet on the same level as in his later works. After the literary conflict with Seabury, Hamilton became a relatively reputable patriotic essayist: two essays criticizing the Quebec Act , one of the Intolerable Acts, were published in the Rivington press. Another series of essays was published from November 9, 1775 to February 8, 1776, so while Hamilton was in the military, under the name Monitor Essays in the New York Journal by John Holt.

War of Independence (1775–1782)

Early military career

John Church Hamilton reports that his father began to familiarize himself with weapons as early as the winter of 1774/75. When news of the outbreak of war through the fighting in Lexington and Concord reached New York, Hamilton joined a militia. He was assigned to a group led by Edward Fleming who, according to Robert Troup (who joined the same militia), wore green uniforms and a hat that read "Freedom or Death". In military records, the "Corsicans" resemble the descriptions of Troup, Fish, and Mulligan most. Later, when Fleming was promoted to military administration, the Corsicans likely changed their name to Hearts of Oak. During training, Hamilton was committed, which is why he became an officer candidate in June 1775. Hamilton's first battle was on August 23, 1775. The Asia , a Crown ship, reached New York, posing a great threat to a patriotic battery at Fort George . To get the battery's cannons to safety, Hamilton volunteered with 15 others. When the ship shot at the volunteers, it hit a nearby inn.

On February 23, Colonel Alexander McDougall , who was supposed to raise an artillery company for the defense of New York , proposed Hamilton as captain . After he had been examined, he received the rank on March 14, 1776. According to Hercules Mulligan, this promotion involved the recruitment of 30 men, 25 of whom they are said to have recruited on the first day. The core of the new troop, however, formed the Hearts of Oak . Hamilton later commanded 86 men, among whom he was very popular for his commitment. He was very strict in military formalities such as uniforms and the correct deployment during military parades. Hamilton's first military action as captain was his involvement in the fortification of New York, which was the target of British attacks after the siege of Boston . There he took part in several skirmishes before the actual British attack, but he did not fight in the first battle in New York, the Battle of Long Island . It was not until the landing at Kips Bay and the subsequent Battle of Harlem Heights , in which British troops landed were able to conquer New York, that he fought with his company and lost all of his heavy artillery. It was in these battles that Hamilton is said to have drawn the attention of General Washington for the first time. Then Hamilton moved with the rest of the army back to White Plains, where the Continental Army was defeated again in the Battle of White Plains . After a subsequent retreat through New Jersey, Washington began, on the urgent advice of its officers, to expand its army to smaller skirmishes (the so-called Fabian strategy , named after the ancient general Fabius ), since the British army had a clear advantage in open battles. Hamilton supported this - he referred Seabury to this strategy as early as The Farmer Refuted . During the retreat, Hamilton stood out in the eyes of Washington especially when crossing the Raritan River , during which Hamilton's company provided cover for the army. The next major military confrontations were the Battle of Trenton on December 26th and the Battle of Princeton on January 3rd, 1777, two major American victories. The Hearts of Oak were involved in these battles, but they did not play a significant role.

Aide-de-camp of Washington

Hamilton became a relatively well-known soldier during the early years of the war, drawing the attention of influential generals such as Lord Stirling, McDougall, Nathanael Greene, and Henry Knox . Some of them had offered him to become their aide-de-camp , but Hamilton turned it down in order to lead a company and gain fame on the battlefield. Only an offer from George Washington on January 20, 1777 convinced him to leave his post and work for Washington. Hamilton's membership in Washington's "family," as his officers' staff was called, did not become official until March 1. He was also promoted to lieutenant colonel .

Among the 32 aide-de-camps in Washington, Hamilton was one of the most important, alongside Robert Hanson Harrison , Tench Tilghman and John Laurens . Some historians even rate him as the most important, resembling a modern Chief of Staff . As Washington's adjutant, one of the main tasks was to draft letters for him. Some of Hamilton's drafts were very significant, such as letters to Congress. From his pen came z. B. An order to Congress to evacuate Philadelphia before a British attack. In addition, Hamilton served as a diplomat for Washington. For example, in November 1777, after the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga , he was sent to Horatio Gates , the victorious general, to convince Gates to move some troops to Washington. Although Gates initially showed himself to be resistant, Hamilton finally convinced him to move two brigades. Like the other aide-de-camps, he played no role in the actual military decisions of the Continental Army, since they did not advise Washington. However, he was assigned minor military duties, such as evacuating Philadelphia supplies to keep them out of British hands.

Hamilton made several contacts among the aide-de-camps. His closest friend was John Laurens, the son of Henry Laurens , whose correspondence was unusually informal for Hamilton. Some historians even suggest a homosexual relationship between Hamilton and Laurens. Laurens and Hamilton built another friendship with the Marquis de La Fayette , a French nobleman who voluntarily served in the Continental Army. Outside the army, the post as aide-de-camp was a great way to meet members of the elite who met with Washington, such as general and member of the Continental Congress Philip Schuyler . Elizabeth Schuyler arrived with her father and was courting Hamilton. After an engagement in March 1780, they married on December 14, 1780 in the home of the Schuylers in Albany . In doing so, Hamilton allied itself with the influential New York Schuyler family and their leader, Philip Schuyler. He also befriended his sister-in-law Angelica Schuyler Church , who was married to British MP John Barker Church . He was often accused of having a romantic relationship with her.

While working as an aide-de-camp, he repeated and read several works that he described in his notebook. In the book he noted comments on many ancient books, such as Plutarch's double biographies, Demosthenes ' speeches and Cicero's works. Plutarch's biographies of Romulus and Theseus , two monarchs, and of the Roman king Numa Pompilius and Lycurgus , two legislators, particularly influenced Hamilton's view of the world. When reading the ancient texts, he focused on the political, but also economic, cultural and religious institutions of the society of that time. He also read more recent works such as those by David Hume, Michel de Montaigne , Francis Bacon and Thomas Hobbes . One of his most significant readings was the Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce written by Malachy Postlethwayt , a detailed description of the geography, politics, and economics of Europe that formed much of Hamilton's knowledge of trade. In the period from 1780 to 1781, Hamilton wrote three essays in the form of letters to three different addressees and six essays called The Continentalist Essays under the pseudonym AB in the New-York Packet , depicting Hamilton's political beliefs at the time, nationalism. (a) In these, Hamilton discusses three issues: the weakness and possible reforms to strengthen the Continental Congress, financial reforms and his general views on human nature. The fundamental mistake of the Congress is its powerlessness against the states; he had no decision-making power over war or peace, since the states had the power over the armies, which, however, belonged to the hands of Congress. Far more important for Hamilton, however, was the potential crisis in peacetime: Congress gave the states too much power over the coffers. Another fundamental problem was the lack of a strong executive, but Hamilton's main goal was reform to get the nation's financial position back on track. A constitutional convention should be set up to discuss these problems and to initiate reforms to eliminate them. Furthermore, Hamilton proposes detailed financial reforms and supports the actions of the new Superintendant of Finance Robert Morris .

Battle of Yorktown

While serving as aide-de-camp, Hamilton sought fame as a leader on the battlefield. As the war drew to a close, he unsuccessfully asked Washington for a post in the field. After a small argument with Washington in February 1781, he resigned from his post. Presumably Hamilton expected Washington to make him head of a battalion straight away, but Washington failed to meet those expectations. Even so, Hamilton insisted on this in several letters and visits. In order to enforce his demands, Hamilton finally threatened to resign from his post as Lieutenant Colonel, whereupon Washington immediately placed him in command of a battalion of light infantry .

That battalion would lead Hamilton in the Battle of Yorktown . Washington planned namely, together with the allied French fleet under the Comte de Grasse and the Comte de Rochambeau , to conquer the British position in Yorktown under the leadership of Lord Cornwallis and to win the War of Independence with this battle. Like the rest of the army stationed near New York, Hamilton's battalion had to be moved. It took almost the whole of September for this. For defense, Cornwallis had built ten redoubts , which became the main target of the American and French attacks. On October 6th, French engineers began digging two trenches to cut off Cornwallis. To complete it, redoubts number nine and ten, which were closest to the French and American positions, had to be taken. Hamilton led the attack on Redoubt ten and captured it in a few minutes. Redoubt nine was also taken by French troops under the Comte de Rochambeau and the trenches were completed, whereupon Cornwallis surrendered. De facto , the war ended with that, but de jure it did not end until the Treaty of Paris in 1783. In March 1782, Hamilton gave up his military post.

Legal practice

The New York Supreme Court in January 1782 suspended the three-year training requirement for soldiers who had studied law prior to serving in the Revolution. This enabled Hamilton to study himself, which he completed six months later with his successful bar exam. He then wrote a legal handbook, as is customary for new lawyers. The 40,000 word and 177 page Practical Proceedings in the Supreme Court of the State of New York became the standard work of New York law. It was not until William Wyche's New York Supreme Court Practice , based on Practical Proceedings in the Supreme Court of the State of New York , that it replaced it in this role in 1794.

Hamilton specialized in defending former loyalists who were increasingly attacked under the Confiscation Act , Citation Act and Trespass Act , with the Rutgers v. Waddington stands out in particular. He defended Joshua Waddington against Elizabeth Rutgers, who sued him for $ 8,000 under the Trespass Act . The case ended with the payment of only $ 800. This was followed by 44 or 45 other cases under the Trespass Act and 20 under the Confiscation Act and the Citation Act . Hamilton defended former loyalists in two articles entitled Letter from Phocion , named after the ancient Athenian general Phocion . Support for the economically influential loyalists in New York was sharply attacked in many radical newspapers.

In 1784, Hamilton founded the Bank of New York , one of the oldest banks in North America.

Beginnings in politics

Confederation Congress

Even while he was aide-de-camp in Washington, he was disappointed by the Confederation Congress . The main reasons for this were corruption and the inability of Congress to collect taxes, which resulted in acute money problems, which resulted in underpaid soldiers.

Hamilton was elected as one of five delegates from New York to the Confederation Congress in Philadelphia. He reached it in late November 1782. Together with James Madison , he fought to provide the Congress with stable income in order to reduce the high war debts. Both supported a 5% tariff on all imports, which Rhode Island strongly opposed. A committee with him and Madison tried to convince Rhode Island, but now Virginia voted against customs, whereupon he was abandoned.

Unpaid soldiers threatened rebellion in a petition on January 6, 1783, of which Hamilton Washington warned in a letter written on February 13. In that letter, he recommended Washington to use this opportunity to raise money for Congress. Washington's reply, written March 4, thanked Hamilton for the warning, but refused to take advantage of the army. Washington defused the situation by addressing the soldiers personally. This went down in history as the " Newburgh Conspiracy ".

Constitutional Debate and Federalist Papers

Hamilton represented New York with Egbert Benson in 1786 at the Annapolis Convention , where they were to decide on trade policy with five other states. The twelve delegates decided between September 11 and 14 that the disputes between the states were symptoms of the weak national government, which is why they would ask the Confederation Congress to convene a convention of all states in Philadelphia in May to change the articles of confederation. The request was made by Hamilton.

New York sent Hamilton to the Philadelphia Convention together with John Lansing and Robert Yates , two opponents of a stronger national government . Each state had one vote in the Convention, so that Hamilton was in the minority over his two fellow delegates as long as they were present.

There were two major proposals: the Virginia Plan , backed by larger states, and the New Jersey Plan , backed by smaller states. An alternative was proposed in a six-hour speech by Hamilton on June 18. He began his speech by predicting the possible outcome of the convention: it would either maintain the status quo, give the Continental Congress more rights, or form a new government. He then went into what he considered to be the most important issue of the Convention, the power of state governments over against the power of a national government. He saw the power of the state governments as too great and the power of the national government as too little. His argument was the "principles of civil obedience" ( English Principles of civil obedience ) - (to support habit a government) interest (reward for supporting a government), opinion (popularity of governments), habit (enforce opportunity laws) power and Influence (honors, e.g. judiciary) - all of which fought in favor of the state governments, which, according to him, would lead to the collapse of the national government. Finally, he proposed a system of his own: There should be a two-chamber system with a Senate and a House of Representatives, as well as a President with absolute veto power. The President and Senate should be elected for life by landowners elected electors, and the House of Representatives every three years by all men. The two chambers of parliament and the president should be controlled by a supreme court. The controversial plan was never adopted, but the Virginia plan seemed less radical compared to Hamilton's plan. It has even been suggested that this was Hamilton's real intention.

Hamilton returned to New York on June 29th after another speech. He wrote in a letter to Washington that he had "serious and deeply saddened" ( English seriously and deeply distressed ) on the Convention was. A week later, Lansing and Yates also returned to New York. Hamilton then shuttled back and forth between New York and Philadelphia and was the only New York delegate present, but he couldn't vote without her. In New York he was involved in a spring war against the anti-federalist George Clinton . The constitution was then signed by Hamilton among others on September 17th in accordance with the Connecticut Compromise .

After the constitution of the United States of America was signed on September 17, 1787, two factions were formed: supporters of the constitution (and thus of the central government), called federalists , and opponents of the constitution, called anti-federalists . Hamilton, one of the foremost supporters of the Constitution, along with other federalists, planned a series of articles called the Federalist Papers . Although Hamilton also wanted to recruit Governor Morris and William Duer , he could only convince John Jay and Madison. Each writer should cover his or her areas of expertise: Jay foreign policy, Madison the anatomy of the new government, and Hamilton the executive, judiciary, military, and taxation. The essays were published under the pseudonym Publius . Since Jay could only write five essays due to illness, the 85 Federalist Papers were mainly written by Madison (29 essays) and Hamilton (51 essays). They kept a set schedule of four articles a week published in the Independent Journal .

Presidential, governor and senate elections of 1789

The new constitution provided for the post of president, for which popular Washington was predestined. The electors sent by the states should receive two votes. The runner-up became Vice President; the candidate was John Adams . Hamilton, who actually supported the federal Adams, was concerned that Adams might reach a stalemate with Washington, which would be an embarrassment for the new Electoral College . He asked seven or eight electors to vote someone other than Adams to avoid this scenario. Adams misunderstood this action, which he called "dark and dirty intrigue" ( English dark and dirty intrigue ), as an attack on him. Washington won the election unanimously. John Adams (pictured) became Vice President with 34 out of 69 electors.

At the same time, gubernatorial elections were held in Hamilton's home state, New York. The top candidate was the re-running anti-federalist George Clinton, an enemy of Hamilton. The federalist contender was Robert Yates, who was an anti-federalist at the Philadelphia Convention. The campaign began with 16 articles by Hamilton published under the pseudonym HG in the Daily Advertiser . The anti-federalists' occasionally personal response was written by several authors. Clinton defeated Yates.

The 1788 Senate elections in New York and North Carolina did not take place until 1789, since the parliaments there, which the senators had to elect, had not yet met. ( Senators have only been directly elected since the 17th Amendment to the United States Constitution .) For this election there was a pact between two eminent politicians, Philip Schuyler, supported by his son-in-law Hamilton, and Robert R. Livingston. The Schuyler and Livingston families were among the three richest and most powerful clans in New York, along with the Clintons. This pact provided for Philip Schuyler himself and James Duane , an ally of Livingston to be elected to the Senate, supported by both parties. But this did not happen because Schuyler, through influence from Hamilton, instead of Duane, supported Hamilton's former classmate Rufus King . King's victory drove Livingston into the anti-federalist camp and created powerful opponents for Hamilton in his home region.

Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury in Washington's Cabinet

Hamilton was appointed on September 11, 1789, nine days after the Treasury Department was created.

The constitution did not create a cabinet , so the actions of Hamilton and the other members of Washington's cabinet (Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson , Secretary of War Henry Knox and Attorney General Edmund Randolph ) defined their ministries for the future. In particular, the specific tasks of the ministries were controversial, so Hamilton participated in almost every matter. His influence as an adviser was so great that some historians consider him " Prime Minister of the State " Washington.

Report on Public Credit and Compromise of 1790

Ten days after Hamilton had been appointed Minister of Finance, on 21 September, the Congress called for a report on the national credit ( english Report on Public Credit ), for which were granted a period of 110 days to him. The subject of the report became the immense debt of the United States, which has been one of the national government's greatest problems since Hamilton's membership in the Continental Congress. Debt could be divided into three categories: state debt, national government debt whose creditors were foreign, and national government debt whose creditors were domestic.

With regard to foreign debt, almost all of which stemmed from the American Revolution, the consensus was that it was more important than domestic debt and that it should therefore be paid off first; but this was not possible without a tax increase. Hamiltons partially solved the problem by postponing the deadline for paying France to first pay off the debts to Dutch merchants. Part of the domestic debt consisted of promissory notes that soldiers had been used to pay during the revolution. Convinced that they would never be repaid or out of sheer financial difficulties, many veterans sold the promissory notes to speculators. Discrimination was proposed, i.e. instead of paying the speculators for the promissory notes bought, paying the soldiers as the original recipients of the promissory notes. The popularity of the proposal can be explained by the unpopularity of the speculators, also known as bloodsuckers . The rest of the domestic debt consisted mainly of bonds , the "loan office certificates". State debts, like national government debts, stemmed from the revolution. There was a clear difference between states with still high debts (e.g. South Carolina and Massachusetts) and states that had already paid their debts (e.g. Virginia and North Carolina). Hamilton also had to clarify the question of whether one should simply repay the debt or finance it, i.e. keep it at a low level. Proponents of direct repayment saw debt as a curse that should be ended immediately by all possible means, while proponents of financing saw debt as a blessing that, if properly managed, ensured economic growth and stability.

Hamilton saw the lack of money as one of the main causes of these problems. As a solution, he suggested in the report that debt to the government be converted into money, which would help every class in the community if the debt was well funded. He then declared discrimination to be damaging to the government's reputation, as it punished speculators who trusted the government while it rewarded soldiers who did not trust the government. He proposed a centralization of the debt under the national government, which prevented a chaos of several overlapping debt policies. Another argument in favor of this plan was based on the problem that countries with high debt levied higher taxes than countries with low debt, which triggered immigration to the latter. The foreign debts with only 4 or 5% interest should be taken over directly, domestic debts received a more complicated treatment: creditors should be given several options to collect their debts, e.g. B. Land in the Frontier area . The report also saw new taxes on e.g. B. tea, wine, coffee and whiskey. In the end, Hamilton advocated financing debt.

The report was read to the House of Representatives on January 14, 1790. It was received controversially; several politicians saw it as an attempt to give the national government more power or as a corrupt pact with speculators. The debate began on February 8th with Hamilton's plan to pay speculators for the promissory notes they'd bought from veterans. In a speech on February 11, James Madison, from whom Hamilton had expected support, turned out to be opponents of the plan, which he saw as a betrayal of the veterans. Nonetheless, Hamilton's plan was approved by 36 votes to 13. The debate turned to Hamilton's plan to centralize state debt under the national government. There was a clear cut between states with still high debts (e.g. South Carolina and Massachusetts) that benefited from the plan, and states that had already paid their debts (e.g. Virginia and North Carolina) that benefited from the plan indebted states did not want to help. The agrarian southern states in particular, led by the Virginia Madison and Secretary of State Jefferson, who had recently returned from his mission to the Kingdom of France , rejected this plan. Despite heated debate on the part of Hamilton, the Assumption Bill was rejected on April 12 by 31-29, and all debates on the plan ended two weeks later.

At the same time, Madison and Jefferson were trying to convince Congress to consider a place on the southern Potomac River as capital, but they too did not have a majority in Congress. Both parties saw a compromise as the best way to implement their respective proposals. According to Jefferson, it was during this time that he encountered a beleaguered Hamilton who claimed that if the Assumption Bill were rejected , he would likely have to resign. Jefferson also claims that they met Madison the following day, July 20th. They decided to jointly support the Residence Act and the Assumption Bill . They were passed on July 10th and 26th.

Report on a National Bank

On August 9, Congress called for another report, which Hamilton dedicated to the endorsement of a national bank . Unlike many of his contemporaries, Hamilton advocated a national bank , influenced by the theories of Adam Smith and Malachy Postlethwayt and the burgeoning banks of Europe.

His first argument in favor of a national bank was that money in individual chests would do nothing for the economy, while money in banks would stimulate the economy thanks to the multiple functions of a bank. Then he spoke to paper money, which was unpopular because of the inflated, worthless paper money, the Continentals . Since the American economy lacked money (e.g. tobacco recipes were already being used as money in the south), Hamilton wanted to reintroduce paper money. In order to avoid the problems of the Continentals , the National Bank should print paper money that could be exchanged for coins. This would trigger an automatic self-correction: if the bank printed too much money, citizens would exchange their paper money for coins, whereupon the bank would withdraw part of the paper money. To prevent corruption, the directors should be changed regularly.

On December 14, 1790, the report was read to the House of Representatives, followed on January 20, 1791 by a proposal for the establishment of a national bank that would exist for 20 years and be built in Philadelphia. Once again, much of the criticism came from the agrarian southern states, who feared that a national bank would make the traders in the northern states too powerful. Madison attacked in speeches on February 2 and 8, 1791, the proposal on the basis that a national bank would violate the constitution. Even so, he was adopted on February 8 at 39:20; What is remarkable is the heated debate between the northern states, who generally voted in favor, and the southern states, which unanimously voted against. Madison tried to convince Washington to veto, whereupon he called his cabinet for help. Jefferson and Randolph supported a veto, but Hamilton convinced Washington to sign the founding document of the First Bank of the United States in a 15,000-word treatise . This paper is one of the first descriptions of " implied powers (" English implied powers ) that are not described in the constitution, but the government still available. Daniel Webster later cited this National Bank defense in the McCulloch v. Maryland .

Report on the Mint

To further help the American economy against the lack of money, Hamilton proposed in the Report on the Mint on January 28, 1791 the establishment of a mint and a coin reform. The dollars should be based on the decimal system and be bimetallic . These reforms were implemented with the Coin Act of 1792 , the United States Mint was compromised and assigned to the Jefferson State Department, which was suspicious of Hamilton's influence and powers.

Report on Manufactures

In the motherland of America, England, the Industrial Revolution began in the late 18th century , which triggered an economic boom. Hamilton feared that if the US did not go through industrialization, it would be economically behind. To prevent this, Hamilton granted industry subsidies as early as 1789 , e.g. B. to the New York Manufacturing Society and, more importantly, the Society for the Encouragement of Useful Manufactures (abbreviated SUM ). He was assisted by the assistant finance minister, Tench Coxe . On January 15, 1790, Congress requested a Report on Manufactures , which it did not submit until almost two years later, on December 5, 1791. The motivation for this report was military; In the event of war, the US should not be dependent on trade with other powers, but Hamilton used it as a platform for a plan for industrialization.

From the beginning, Hamilton emphasized that his new industrial system would not replace the then prevailing agricultural system, but would exist alongside it. Even so, he attacked the economic system of agraism propped up by Adam Smith's wealth of nations . In a large part of the text, Hamilton describes how he imagined the industrial economy: an equal meritocracy . Unlike Smith's plan, trade should be regulated, but these regulations should not be extreme, as Hamilton already preferred a laissez-faire , but control of the economy for the newly founded America due to the aggressive trade policy of the European powers as inevitable looked. This lists goods that should be supported in their manufacture (including copper, coal, wood, wheat, silk, and glass) and explains how they should be supported. He preferred incentives . He devoted only two paragraphs to the actual topic, economics in wartime. His proposals were mainly from the first article of the constitution, specifically stating from the first clause of the eighth section that Congress for defense and welfare care needs ( English Provide for the common defense and general welfare ), founded. Congress paid little attention to the report, yet it was of immense importance to the American school of economics.

Power struggle between Jefferson and Hamilton

In early America, political parties, called factions, were universally hated. For example, according to James Kent , Hamilton at the Federalist , said in his speeches and to Kent himself that factions would ruin the US. Nevertheless, a.o. two clear factions based on foreign policy issues and Hamilton's reforms: the supporters of Madison and Jefferson, called Republicans (later Democratic Republicans ), and the supporters of Hamilton, called federalists . According to Jefferson, the Republicans wanted to give the Senate and thus the legislature (controlled by the individual states) more power, while the federalists wanted to give the President and thus the executive more power. Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick in The Age of Federalism date the founding of the parties to 1792, but some see it, i.a. John Marshall in his biography of George Washington, The Beginnings of Political Parties in the Discussion of a National Bank, in 1791. Jefferson's trips north to recruit allies such as New York's new Senator Aaron Burr , the Hamiltons , also take place at this time Defeated father-in-law Philip Schuyler in the 1790 and 1791 Senate elections . The newly formed parties were not official, they could not put pressure on their members. The majority of Americans did not yet trust political parties and sometimes even saw them as a conspiracy, which is why politicians denied their membership in them.

After the gradual formation of the parties, the political power struggle between Jefferson and Hamilton became more extreme, the parties formed a demonic image of each other: Federalists should be counter-revolutionaries , Republicans anarchists . Jefferson attacked Hamilton in several talks with Washington; i.a. the fear that Hamilton would take over government with the Treasury Department and the claim that Hamilton was a monarchist were often raised. Jefferson interpreted the fact that Washington was not convinced to mean that Hamilton had wrapped Washington around his finger. He began to consider resigning.

The power struggle between Hamilton and Jefferson was also fought in the newspapers: Hamilton was supported by John Fenno's semi-official Gazette of the United States , in return the Gazette was financially supported by Hamilton. Jefferson was supported by Philip Freneau's National Gazette , in which Madison was particularly active.

Washington rated the fighting in its cabinet negatively; he tried to appease him in several letters to Hamilton. Hamilton ignored them and wrote several essays in his defense while Republicans continued to attack. Hamilton was also attacked in Congress, mainly by the Virginians William Branch Giles and Madison, who pushed through several unsuccessful investigative commissions against Hamilton.

Diplomatic relations with France and Great Britain

The French Revolution was viewed as controversial in America after the beginning of the Reign of Terror, after an initial warm welcome : Federalists saw the revolution as a warning of how a revolution could end in terror, while Republicans and a large part of the population saw it as a repetition of the American Revolution. The question of whether to support the revolution became an important issue after France declared war on Great Britain , as trade with both nations was important to American agriculture as well as industry. Hamilton and Jefferson therefore jointly supported a declaration of neutrality, but could not agree on the exact details: Jefferson wanted to use it as a negotiating tool with other nations, while Hamilton preferred a direct declaration of neutrality. Hamilton convinced Washington, which officially announced neutrality on April 22nd . A diplomatic crisis, triggered by the French ambassador Edmond-Charles Genêt (called Citizen Genêt after the policy of revolutionary France ), who tried to stir up pro-revolutionary sentiment among the US population, heightened tensions between Jefferson and Hamilton, with Washington continuing to grow Hamilton stopped. The fighting in the Cabinet lasted until December 31, 1793, when Jefferson resigned and was replaced by Attorney General Edmund Randolph and William Bradford became the new Attorney General . Hamilton also began to consider resigning.

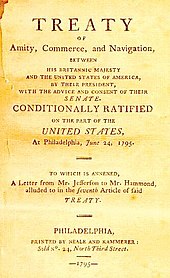

Despite the pro-British stance of American foreign policy, the British government under William Pitt attacked American merchant ships en route to France. This sparked outrage; an army of 20,000 men was being prepared, and Hamilton recommended trading posts to be fortified. Oliver Ellsworth suggested sending an agent to negotiate an anti-war treaty. An obvious candidate, who also supported Ellsworth, was Hamilton, but Washington doubted whether Hamilton would get public support. Hamilton also found that the hostility from Republicans was keeping him from the diplomatic mission. His proposal was Chief Justice John Jay, which Washington accepted. Jay's general goal was decided at a meeting of the leading federalists, thanks to Hamilton's influence, the Jay Treaty , as it was later called, should also deal with commercial issues.

Whiskey rebellion

In March 1791, with the joint support of Madison and Hamilton, the Senate passed a tax on alcoholic beverages, which was mentioned in the Report on Public Credit . The new tax was particularly hated in western Pennsylvania , where breweries were an important part of the local culture and economy, despite a tax cut. A rebellion broke out when two tax collectors totaling 500 men were attacked, causing 6,000 rebels led by David Bradford to rally at Braddock's Field on August 1st. Following the example of the French Revolution, guillotines were set up.

Hamilton's view of the revolt is made clear in a letter to Washington and in several articles published under the pen name Tully in the American Daily Advertiser between August 23rd . The betrayal as which he saw him should be put down with military might. Edmund Randolph , along with Pennsylvania leaders, advocated a more peaceful policy of reconciliation with the rebels. Washington chose a compromise route between the two parties; three plenipotentiaries, including William Bradford, were to negotiate with the rebels. If the rebels did not break up by September 1st, a militia should be deployed. The agents achieved nothing. At Hamilton's suggestion, the militia consisted of 6,000 Pennsylvanians and 2,000 each from New Jersey, Virginia and Maryland. On October 4th, Hamilton, who replaced absent Secretary of War Henry Knox, and President Washington met the Carlisle militia in person . From there, Washington returned in late October, leaving the command to Henry Lee III . The army then marched to western Pennsylvania, the center of the rebellion, where they encountered little resistance.

Hamilton has been portrayed as a despotic tyrant in the Republican press, particularly by Benjamin Franklin Bache and William Findley . Even so, the bloodless suppression of the revolt was generally well received, causing the federalists to win the midterm elections .

Report on a Plan for the Further Support of Public Credit and Resignation

On December 1, 1794, Hamilton announced that he would resign from his post as Treasury Secretary on January 31. His decision was likely shaped by his wife's miscarriage , which he said was triggered by his absence during the Whiskey Rebellion.

Debt was still one of the biggest problems facing the republic, which had to spend 55% of its income on debt servicing. To solve this problem, the congress offered only temporary solutions rather than a general plan that would finally solve the problem. Hamilton annoyed this behavior; he wrote a report to Congress called Report on a Plan for the Further Support of Public Credit , which offered its own plan and was presented on January 19, 1795. The report outlined a plan to pay off the debt within 30 years. The proposed reforms were approved by Congress within just a month. Changes proposed by Aaron Burr and which Hamilton had strongly criticized were not accepted .

Life after ministerial

Supporting the Jay Treaty

The Jay Treaty reached government on March 7, 1795. It was most criticized by Republicans for the immense concessions it made to Great Britain, but it achieved the federalist goal: peace with Great Britain. It was approved by the Senate after an amendment to Article 12, but Washington was reluctant to sign the treaty for fear of public criticism. Hamilton tried to convince him in a letter that analyzed the articles of the treaty individually. He also wrote a series of articles with Rufus King entitled The Defense under the pseudonym Camillus , which defended the treaty. At the same time, Hamilton wrote essays under the pseudonym Philo Camillus , in which he praised Camillus and portrayed the opponents of the treaty as a war hawk.

Republicans questioned the constitutionality of the treaty. Since the treaty also dealt with commercial issues, Republicans wanted it to be adopted by the House of Representatives, but this was condemned and rejected by both Hamilton in his last two The Defense essays and historians. Republicans also demanded that Washington publish the previously secret instructions for Jay, which was also rejected. In the end, they tried not to provide the funds required for the contract, but this was rejected by 51 votes to 48.

Election 1796

Oliver Wolcott Jr. , the new Treasury Secretary, Timothy Pickering , the new Secretary of State, James McHenry , the new Secretary of War, and Washington, who was disappointed in his new cabinet, often asked Hamilton for advice. Perhaps the most important case followed Washington's decision not to run for the third time, setting a precedent that much later resulted in the 22nd Amendment to the United States Constitution . To explain this decision, he wanted to publish a Farewell Address , which he had Hamilton drafted. The manuscript used was a Farewell Address written by Madison at the end of Washington's first term, and an additional section on the major changes in areas such as: B. Foreign policy, written by Washington itself, but Washington called for a completely new form. The aim was to create a timeless document that would inspire all Americans. It was first published in Claypoole's American Daily Advertiser on September 19, 1796 , after which it was quickly recognized and widely circulated as a political masterpiece.

Hamilton, despite his importance in the Federalist Party, did not stand for election, probably because his controversy would have jeopardized a victory. Instead, former Washington Vice President John Adams was nominated as a federal candidate, with Thomas Pinckney becoming Vice President . As a Republican nominee, Thomas Jefferson was nominated with Aaron Burr as vice presidential nominee. Hamilton wanted to prevent the possibility that his arch-rival could be elected president, which is why he supported the South Carolina Pinckney instead of the New England Adam , who would win more votes in the south. Since Adams was still supported by many federalists, Hamilton could not support Pinckney directly and instead wrote several articles under the pseudonym Phocion . These characterized Jefferson as a hypocritical abolitionist who owned slaves against his beliefs ; he was also accused of having sexual relations with one of his female slaves, Sally Hemings . According to Hamilton's calculation, southern slaveholders should be scared and vote for Pinckney (not for Adams, who was an abolitionist) instead of Jefferson. The concept didn't work. Adams was elected President and Jefferson was elected Vice President.

From the start, the relationship between Hamilton and Adams was cool, partly because of choice, partly because of personal differences. Adams saw Hamilton as a snooty womanizer, Hamilton saw Adams as a puritan and oversensitive.

Reynolds scandal

In the summer of 1791, Maria Reynolds visited Hamilton. She told him that her husband was abusing her. Hamilton suggested that they be taken home and financially supported, but a sexual relationship quickly developed that benefited from the absence of Hamilton's wife, Eliza. James Reynolds, husband of Maria Reynolds, soon ran Chantage . It is still unknown to this day whether Reynolds arranged the sexual relationship between Mary and Hamilton for this chantage. The affair ended in the summer of 1792 when Hamilton saw it as too great a political danger.

The situation came to a head when James Reynolds was arrested for fraud along with his friend Jacob Clingman, Frederick Muhlenberg's former scribe . It was about passing on confidential information about the Central Bank's policy to speculators. Clingman testified that Hamilton jointly committed the fraud, with several letters from Hamilton to Reynolds serving as evidence. Together with James Monroe and Abraham B. Venable , Muhlenberg investigated Clingman's allegations. James Reynolds only hinted at his chantage against Hamilton and demanded a release for more information, which Maria Reynolds only gave in incomplete form. When Reynolds fled Philadelphia, the allegations were confirmed in the eyes of investigators. Monroe, Venable and Muhlenberg saw a Hamilton investigation as the final step before informing the President of the incident. They confronted him on December 15th. After they agreed to remain silent, Hamilton revealed his affair with Maria Reynolds in an attempt to dispel fraud allegations.

In the summer of 1797, scandal-seeking journalist James T. Callender published The History of the United States for 1796 , in which he alleged (supported by papers from Monroe) that Hamilton was cheating on James Reynolds. As with Monroe, Venable and Muhlenberg, Hamilton proved his innocence by revealing his affair with Maria Reynolds, this time in public through the pamphlet Observations on Certain Documents Contained in No. V & VI of "The History of the United States for the Year 1796," In which the Charge of Speculation Against Alexander Hamilton, Late Secretary of the Treasury, is Fully Refuted. Written by Himself , better known as the Reynolds Pamphlet . After the pamphlet, Hamilton's reputation was severely weakened, but he remained an important political figure. Hamilton and his family accused Monroe of seeking revenge for his recall from the post of ambassador to France. These accusations almost escalated into a duel, but Monroe's friend Aaron Burr prevented it.

Quasi-war

After the Jay Treaty, tensions with the French Republic escalated ; the American ambassador Charles Cotesworth Pinckney was expelled from France. Adams and Hamilton wanted to improve diplomatic relations with France through a delegation and at the same time strengthen the American military. Federalists Pinckney and John Marshall became, despite protests by leading federalists, among others. also Adam's cabinet, sent with Republican Elbridge Gerry to negotiate a treaty similar to the Jay treaty preventing war. Marshall, Pinckney and Gerry arrived in August 1797 and were officially received by French Foreign Minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord in October . Three representatives of the French side, originally known only as X, Y and Z but later revealed as Jean Conrad Hottinguer , Pierre Bellamy and Lucien Hauteval , demanded huge concessions from the United States as a condition for the continuation of the peace negotiations. The terms set by the French officials included £ 50,000 , a $ 12 million loan from the United States and a $ 250,000 bribe to Talleyrand. A formal apology was also requested from Adams for anti-French comments. While Marshall and Pinckney's demands outraged, Gerry urged patience. News of the delegation did not reach the government until March 4, 1798; the government was shocked. Adams first made a speech to Congress describing the events and calling for military preparation. A little later, the papers of the XYZ affair , as it was later called, were published at the instigation of the Republicans, who expected that the papers would put France in a better light. Unknowingly, they played into the hands of the federalists, whose popularity rose after the outrageous papers were published.

Thanks to the XYZ affair, several federalists, especially Hamilton, saw war with France as a serious possibility, which is why an army was prepared. There were rumors that France would send an army of 50,000 men across the Atlantic to invade. France, with its colony Louisiana, was also the western neighbor of the American republic. Many therefore expected a repetition of the Revolutionary War, with former President Washington in command. However, Washington demanded that Alexander Hamilton, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Henry Knox should form the chain of command, if possible in that order. Adams wanted to place Pinckney and Knox over Hamilton, which Washington did not accept. Eventually Adams relented and Hamilton, already appointed Inspector General , took up his position behind Washington in the expectation that the ailing ex-president would let him actually lead the campaign. Hamilton's manipulation of Washington was one of the beginnings of the later battles between Adams and Hamilton. As Inspector General, Hamilton worked with Pinckney, Washington and the Secretary of War James McHenry in several meetings in November and December 1798 to compose the new army. In these meetings, Hamilton was left with large parts of the decision-making power, but he felt as impotent as in the War of Independence; Bureaucrats in Congress did not provide enough resources, which would make the common soldier unsatisfied. Hamilton proposed that all of the French territory on the western side of the Mississippi be brought into American hands, including the Spanish colony of Florida . He also proposed the establishment of a military academy (which, however, was not implemented as the United States Military Academy until 1802 by President Jefferson ). He was suspected of wanting to use the army to intimidate the Republican opposition, especially since the march south would have led through Virginia. He is said to have even intended to then conquer Spanish Mexico and all of Central America . Consequently, both Republicans and Adams, who rated his proposals as very militaristic and Machiavellian , called him disparagingly Bonaparte or Little Mars . (Ironically, years later, Hamilton's expansion goals were to be achieved peacefully by treaty, namely through his sharpest rival Jefferson, of all things , with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, while the also planned acquisition of Florida was only Adams' son John Quincy Adams , with the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, but the annexation of Cuba sought by Jefferson did not take place and the attempted conquest of Canada in the war of 1812 failed. It was Jefferson who, against his publicly announced convictions, strengthened the central government, in keeping with Hamilton's spirit.)

The disputes between Republicans and Federalists escalated after the XYZ affair. The federalists took advantage of their majority in Congress to take advantage of the Alien and Sedition Acts . These banned the publication of false, scandalous, or malicious writings about the government, but this was almost exclusively used to prosecute Republican publishers. It was a drastic restriction on the freedom of the press . Because of the attacks on him, among others. through Callendar, Hamilton supported the law and used it to arrest David Frothingham . Predictably, the Alien and Sedition Acts outraged the Republicans who attacked them by nullifying the state legislatures of Kentucky and Virginia. First the law, written by Madison, was passed in Kentucky on November 16, 1798; the Virginia law, written by Jefferson, was not passed until December 24th. The federalists saw this as shocking.

France tried to move closer to the USA in order to avoid war, which Adams accepted with the nomination of William Vans Murray as ambassador to France. Adam's decision not to allow an unpredictable war to break out took both political parties by surprise and sealed Adam's political fate. Leading federalists, including from Adam's cabinet, and above all Hamilton, who used the threat from France as a justification for his army (and far-reaching plans of conquest), were shocked. Although the Federal Party agreed to send Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth and North Carolina Governor William Davie along with Vans Murray, this internal party dispute caused the political separation between Adams and Hamilton. On October 15, 1800, Adams held a final meeting with his cabinet about the embassy, after which he ordered the departure of Vans Murray, Ellsworth and Davie the next day in early November. Hamilton then tried one last time to convince Adams of the importance of an army to defend against France, but Adams rejected the idea that France posed an acute threat, which Washington itself considered unlikely. This meeting marked the final break between Adam and Hamilton. When Washington was informed of Hamilton's far-reaching plans, he was shocked and decided to stay out of politics in the future. Only a little later, the death of Washington sealed the end of the army, which was demobilized in mid-June 1800, despite the quality built by Hamilton.

Election 1800

As a decision-making swing state , Hamilton's place of work, New York, was particularly important in the presidential election, but only the federalist-controlled State Legislature, which was re-elected on May 1, voted there. The Republicans, organized by Vice-Presidential candidate Aaron Burr , campaigned vigorously which the federalists led by Hamilton could not surpass; the Republicans achieved a landslide victory that denied Adams a second term. With Jefferson as his successor, the era of the so-called Virginia dynasty began , which was continued by his two closest collaborators and later successors, Madison and Monroe. Possibly because of this defeat, Adams shortly thereafter fired his ministers, whom he saw as Hamiltonist traitors, in connection with personal attacks on Hamilton.

On August 1, 1800, Hamilton wrote an attacking letter to Adams, which he renewed on October 1 because of a lack of response from Adams. Again, Adams didn't answer the letter. As in the 1796 presidential election, Hamilton actually supported the vice-presidential candidate, this time Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. The high federalists, as the supporters of Hamilton were called, were awaiting a critical open letter to Adams, which would prevent federalists from voting for Adams and win a election for Pinckney. At the same time, however, it was feared that such a letter would only widen the cracks in the Federalist Party. The letter, entitled Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq. President of the United States , confirmed the fears: he portrayed Adams as a paranoid madman, but still called for his election to prevent a victory for Jefferson. The criticism of the letter was so strong that even high federalists distanced themselves from Hamilton. An influence on the choice is doubtful.

Jefferson and Burr, whom the Republican Party named as Vice-Presidential Candidates due to his success in the New York elections, both received 73 votes, in which case the House of Representatives would have to decide the election. Although the Republicans had won the House of Representatives in the election, they did not take it over until January, which is why the Federalists controlled the House in a lame duck session. They wanted to vote for Burr, but because each state would vote individually and it would take a majority of nine votes to win, there was a stalemate in the House of eight for Jefferson against six for Burr, with two abstentions. Unlike many federalists, Hamilton was very critical of Burr, which is why he wanted to dissuade the federalists from his election. The two former officers had known each other for a long time and had often stood against each other as lawyers in New York. Hamilton's efforts only bore fruit after 35 ballots: the House of Representatives voted for Jefferson with ten votes and Burr with five votes, with one abstention. Jefferson and Burr were inaugurated as President and Vice President on June 4, 1801.

After Jefferson was elected, Hamilton withdrew from the national level to the regional and legal levels. He also focused on his family, for whom he had the Grange estate built from 1800 to 1802 . Under the influence of his Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin , Jefferson kept Hamilton's financial plan, but he wanted to cancel several of Adam's nominations for judicial positions, which led to the Marbury v. Madison led. In order to create a platform against Jefferson in New York, Hamilton founded the New York Evening Post with some investors from among the federalists , of which William Coleman was the editor.

Philip Hamilton dies

Philip Hamilton , in whom his father had great expectations, fought on November 22, 1801, a duel with the Republican attorney George Eacker , who had criticized Alexander Hamilton. He was advised by his father not to fire his shot or into the air. True to this advice, Philip Hamilton did not shoot at first, but Eacker killed him. The death of his son hit Hamilton very hard, he mourned for months and was only able to respond to expressions of condolences after four months. Influenced by this and, as he was assumed, by the atheism of the French Revolution and the deism of Jefferson, he turned back to Christianity.

Return to legal practice

Hamilton's legal practice suffered from his employment as an inspector general, as clients, despite his quality as an attorney, preferred attorneys with more time. After the dissolution of the army, however, he was able to devote more time to his legal practice. Before the election in New York, he and Aaron Burr defended People v. Weeks succeeds Levi Weeks, who was accused of murdering his fiancée. On several occasions, Hamilton defended federal publishers who were persecuted due to the change of government. The case of People v. Croswell , where he defended federal publisher Harry Croswell against defamation charges in January 1803 . Here he argued that the truth of the defamatory statements must also be taken into account, which Judge Morgan Lewis refused. In mid-February 1804, he requested a retrial for Croswell in the New York Supreme Court, which was rejected regardless of the strength of Hamilton's argument.

death

Vice President Burr was not re-elected as Jefferson's runner-up candidate for the 1804 Republican election. This meant the political end of Burr in the Republican Party. Even before the end of his term in office in early 1805, he was looking for a fresh start in New York, where he wanted to be elected governor supported by a coalition of federalists and a few republicans. Only at the price of being able to ally themselves with the actually Republican-minded burrites did many federalists believe that they could again gain a majority in New York. In order to form this coalition, Burr is said to have promised the so-called Essex Junto around Timothy Pickering , which had a secession of New England as its goal, the annexation of New York to the new state. (Later historians, however, have not only relativized the extent of this conspiracy , but also denied Burr's involvement.) Even so, Burr clearly lost the election to Republican candidate Morgan Lewis . Burr and his supporters saw the reason for his defeat in a scheme by Hamilton that prevented the extreme federalists from electing Burr. Although Hamilton had already opposed Burr's candidacy in the Federalists' first caucus , historians doubt that this would decide the election. A report of how Hamilton allegedly made disrespectful comments about Burr at a dinner in Albany found its way into the press. Vice President Burr was so hurt in his honor that he challenged Hamilton to a duel . This form of settlement of honor disputes was still widely accepted socially in the United States - both Burr and Hamilton had fought duels before. In New York, however, dueling was forbidden, so duelists usually met on the other bank of the Hudson in the Weehawken Forest in New Jersey , where Philip Hamilton's duel had also taken place.

During the duel on the morning of July 11, 1804, Burr fatally wounded Hamilton with a shot in the abdomen. The exact process is still the subject of much speculation. In the days leading up to the duel, Hamilton not only drew up his will, but also made a few personal remarks about his decision not to aim at the opponent with at least the first of his duel balls, but to waste the first shot - to appease Burr, however also, because a duel is fundamentally contrary to his religious convictions. As a result, Hamilton would have accepted his own death or willingly brought it about. Burr's second William P. Van Ness claimed that Hamilton fired several seconds in front of Burr (and missed well), while Hamilton's second Nathaniel Pendleton claimed that Burr fired first and that Hamilton's shot was only involuntarily triggered by Burr's bullet. An examination of the pistols in 1976 found that Hamilton's pistol was easier to pull. It is therefore possible that Hamilton's shot was accidentally fired while aiming at Burr. However, a statement by Hamilton to Pendleton before the duel speaks against this, in which he claims that he does not use a hair trigger , as this trigger was called.

Hamilton's death was received with dismay in New York. His funeral procession was attended by thousands; Hamilton's friend, Governor Morris , gave an eulogy with the grieving and pathetic sons of Hamilton. Even the city's Democratic-Republican Council ordered a day of mourning. Hamilton's final resting place is in the graveyard of Trinity Church in New York.

Afterlife

Hamilton in popular culture

The rise of Alexander Hamilton from orphaned in the Caribbean to founding father of the United States of America was brought to the stage by Lin-Manuel Miranda , son of Puerto Rican parents, with the successful hip-hop musical Hamilton . The Broadway play became a crowd puller and won a Grammy Award , a Pulitzer Prize and eleven Tony Awards . A recording of the musical was released on July 3, 2020 on Disney + .

The film Alexander Hamilton was made in 1931 based on the play of the same name.

Hamilton moment

In 1790, as Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton converted US state debt into federal debt. Those should be paid for with high income through joint import duties . According to Hamilton, these debts arose in the American Revolutionary War against the British.

The German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz compared an EU borrowing of 500 billion euros because of the COVID-19 pandemic in order to minimize the increased risk of national bankruptcies with the help of German and French payments in southern Europe with Hamilton's act.

literature

- factories

- Harold C. Syrett (Ed.): The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 27 volumes. Columbia University Press, New York 1961-1987.

- Julius Goebel, Jr. (Ed.): The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton: Documents and Commentary. 5 volumes. Columbia University Press, New York 1964-1981.

- Joanne B. Freeman (Ed.): Alexander Hamilton: Writings. Library of America , New York 2001.

- Noble E. Cunningham : Jefferson vs. Hamilton: Confrontations That Shaped a Nation , Boston, Massachusetts [u. a.]: Bedford 2000, ISBN 0-312-08585-0 .

- Biographies

- Ron Chernow : Alexander Hamilton . Penguin, New York 2004, ISBN 1-59420-009-2

- Broadus Mitchell: Alexander Hamilton. 2 volumes. Macmillan, New York 1957-1962.

- Gerald Stourzh : Alexander Hamilton and the Idea of Republican Government. Stanford University Press, Stanford 1970.

- Forrest McDonald : Alexander Hamilton: A Biography W. W. Norton & Company , New York and London 1979, ISBN 978-0-393-30048-2

- Jacob Ernest Cooke : Alexander Hamilton. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1982, ISBN 978-0-684-17344-3 .

- John Chester Miller: Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox. Harper & Row, 1959 ISBN 978-0-06-012975-0 .

- Lawrence S. Kaplan: Alexander Hamilton: Ambivalent Anglophile. ( = Biographies in American Foreign Policy, Number 9 ) Rowman and Littlefield. 2002 ISBN 978-0-8420-2878-3 .

- John Lamberton Harper: American Machiavelli: Alexander Hamilton and the Origins of US Foreign Policy Cambridge University Press. Cambridge 2004

- Thomas K. McCraw: The Founders and Finance: How Hamilton, Gallatin, and Other Immigrants Forged a New Economy Harvard University Press, Cambridge and London 2012

- Special studies on individual aspects

- Douglas Ambrose, Robert WT Martin (Editor): The Many Faces of Alexander Hamilton: The Life and Legacy of America's Most Elusive Founding Father New York University Press. New York 2006

- Richard Sylla and David J. Cowen: Alexander Hamilton on Finance, Credit, and Debt Columbia University Press. 2018

- Micheal E. Newton: Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years Eleftheria Publishing, 2015, ISBN 978-0-9826040-3-8

- Stephen F. Knott: Alexander Hamilton and the Persistence of Myth. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002, ISBN 978-0-7006-1157-7 .

- Thomas Fleming: Duel. Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Future of America. Basic Books, New York 1999.

- Arnold A. Rogow: A Fatal Friendship: Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Hill and Wang, New York 1998.