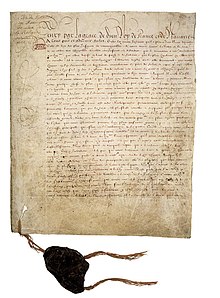

Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes (French: Édit de Nantes ) of 1598 granted the Calvinist Protestants ( Huguenots ) in Catholic France religious tolerance and full civil rights, but on the other hand fixed Catholicism as the state religion. Thus it temporarily put an end to the age of religious wars between Huguenots, Catholics and royalty ( Huguenot Wars ).

Henry IV (Heinrich von Navarra), who himself converted from Protestantism to Catholicism after his accession to the throne and tried to pacify the country after his victory over the Catholic League, who was fighting him , signed the edict on April 13, 1598 in Nantes . It granted the Calvinists freedom of conscience and the free exercise of religion in public, with the exception of Paris and the surrounding area and in cities with bishopric or royal castles.

Noble Huguenots were allowed to attend private services in their homes. The Protestants were allowed to build churches ( called temples ), their pastors were to be paid by the state and released from certain obligations. The edict also guaranteed the Protestants full civil rights; B. the right to hold public office, and it established a separate chamber in the Parlement of Paris, the Chambre de l'Édit , to settle differences of opinion that could arise from different interpretations of its provisions. In addition, the Protestants should be able to keep those fortified cities that they had in their power in August 1597 (around 100) for a further eight years as places de sûreté ; the cost of stationing the crews was to be paid by the king.

The edict also confirmed Catholicism as the state religion and restored the possibility of practicing the Catholic religion wherever it had been prohibited during the previous wars. In fact, it made any further expansion of Protestantism in France impossible. Nevertheless, the Pope ( Clement VIII ), the Catholic priesthood and the parliaments in France braced themselves against the edict; one tried to interpret it as narrowly as possible.

Cardinal Richelieu, for his part, saw the political provisions of the edict as a danger to the absolutist state and annulled them in places in the Peace of Alès in 1629 .

On October 18, 1685, King Louis XIV revoked the edict in its entirety in the Edict of Fontainebleau , Édit de Fontainebleau . The French Protestants were thus deprived of all religious and civil rights. Hundreds of thousands fled within a few months, mainly to the Calvinist areas of the Netherlands , the Calvinist cantons of Switzerland and Prussia ( Edict of Potsdam ).

The act of signing the Edict of Nantes is depicted on a relief on the Geneva Reformation Monument.

literature

- Ernst Mengin (Ed. And Vorw.): The Edict of Nantes - The Edict of Fontainebleau. Gross, Flensburg 1963.

- Heinz Duchhardt (ed.): The exodus of the Huguenots: the repeal of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 as a European event. Böhlau, Cologne / Vienna 1985, ISBN 3-412-07385-7 .

- August Lebrecht Herrmann: France's religious and civil wars in the 16th century. Voss, 1828.

- Robert J. Knecht: Renaissance France, 1483–1610. Blackwell Classic Histories of Europe, John Wiley & Sons, 2001, ISBN 0-6312-2729-6 .

- Robert J. Knecht: The French Wars of Religion, 1559–1598. Seminar Studies in History, Longman, 2010, ISBN 1-4082-2819-X .

Web links

- The Edict of Nantes (French)

- Literature on the Edict of Nantes in the catalog of the German National Library