Edict of Fontainebleau

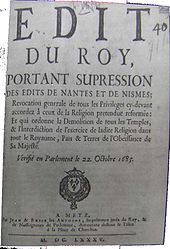

In the Edict of Fontainebleau ( French Édit de Fontainebleau ), better known in France as the "révocation de l'édit de Nantes" ("Revocation of the Edict of Nantes "), King Louis XIV revoked it on October 18, 1685 at Fontainebleau Castle Edicts of his predecessors, the Edict of Nantes and the Edict of Grace by Alès . With the Edict of Nantes in 1598, his grandfather, King Henry IV , guaranteed the French Protestants freedom of religion and ended the more than thirty-year Huguenot Wars after St. Bartholomew's Night. 1629 hadLouis XIII In the edict of grace of Alès, the freedom to hold synods is restricted and the fortified (refuge) places for Protestants are abolished ( French places de sûreté protestantes ).

The edict and its consequences

In the new edict, Ludwig affirmed Catholicism as the state religion and not only issued a ban on Protestant worship , which in France was primarily based on the teachings of Calvin . It announced the destruction of the still existing Reformed places of worship ( French les temples ). Any pastors who were not ready to convert immediately were expelled from the country within two weeks. Protestants, however, were allowed to stay in France if they refused to gather to practice their religion. However, Protestants lost their civil rights, could no longer marry or acquire property. Therefore only a few made use of this possibility.

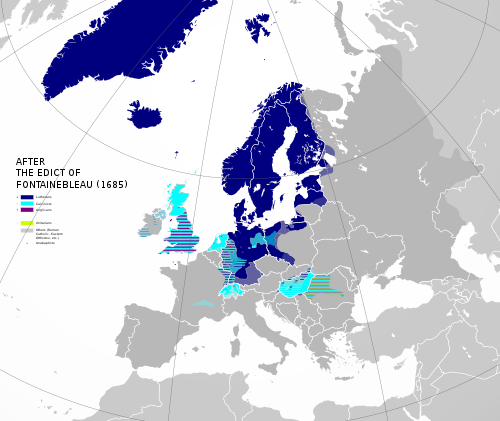

The ban hit the Reformed Church of France hard because it was consistently enforced. In particular from the southern French provinces of Languedoc , Roussillon and Dauphiné , where numerous Huguenots lived, as the Protestants were called in France, many of them fled to other Protestant countries, in particular to the Netherlands, the Palatinate, Switzerland and Prussia . Between 1685 and 1730, around 150,000 to 200,000 of the approximately 730,000 professing Huguenots left the country. These included a disproportionately large number of members of the nobility and the commercially active bourgeoisie, which meant considerable bloodletting for the French economy and ultimately a gain for escape destinations such as Switzerland and Prussia. The Brandenburg envoy Ezekiel Spanheim helped many emigrants to leave the country.

The French possessions in Alsace (including the city of Strasbourg ) were excluded from the Edict of Fontainebleau , as these were virtually considered foreign possessions of the crown. The Protestant denomination was allowed to continue to be practiced here, even if the French authorities tried to favor the Catholic Church.

The Edict of Fontainebleau also had serious foreign policy consequences. Opposition to England and the Netherlands intensified. Protestant states like Brandenburg-Prussia under the Great Elector turned away from France.

Since Protestantism could not be removed with the stroke of a pen, Ludwig tried a military solution in the years after 1700. He sent troops into the core areas of the Protestants, which resulted in cruel acts of war in the Cevennes . Here the rebellious camisards managed to offer resistance in the mountainous region for several years, but hundreds of villages were destroyed and depopulated.

Since most of the Protestant pastors had also left France, lay people often took over their functions. They preached secretly in remote places, called le désert ("wasteland / desert"). If caught, they could face galley or execution as punishment . These lay preachers were usually people who, through their ecstatic states and prophetic speeches, seemed called to their role by God. They created the movement of the inspired , which reached the rest of the continent via England, where they were called French prophets , and in the Protestant countries had a decisive influence on the wing of pietism that was critical of the church .

A few years after his death , his sister-in-law, Liselotte von der Pfalz , wrote the following about the motivation of Louis XIV, who in the first decades of his rule had given little importance to religious matters :

"Our s (eliger) king ... didn't know a word about the h. script ; he had never been allowed to read it; said that if he only listened to his confessor and talked about his pater noster , everything would be fine and he would be completely godly; I often complained about it, because his intention has always been sincere and good. But he was made to believe , the old Zott and the Jesuwitter , that if he plagued the Reformed, that would replace the scandal that he committed with double adultery with the Montespan . This is how you betrayed the poor gentleman. I have often told these priests my opinion about it. Two of my confessors, pere Jourdan and pere de St. Pierre , agreed with me; so there were no disputes. "

It is unclear what roles the Archbishop of Paris, Hardouin de Péréfixe de Beaumont , and the king's confessor, the Jesuit Père de Lachaise , and the king's secret wife, Madame de Maintenon , played in this, but they should not be negligible have been.

Liselotte, who was originally a Calvinist herself and had only converted to Catholicism because of her marriage, achieved the release of 184 Huguenots with her son, the now regent of France, Philippe II d'Orléans , just one month after the king's death in 1715 . including many preachers who had been held in French galleys for many years . However, she also saw the opportunities presented by the Huguenots' emigration to the Protestant countries:

“The poor Reformed ... who settled in Germany will do the French in common. Mons. Colbert is supposed to have said that many are subject to kings and princes wealth, therefore wanted everyone to marry and have children: so these new subjects of the German electors and princes will become wealth. "

It was not until the Edict of Tolerance at Versailles in 1787 and shortly afterwards the Declaration of Human and Civil Rights of 1789 and the Constitution of 1791 during the French Revolution that religious persecution ended and established full religious freedom for Protestants and other religious minorities in France.

literature

- Anna Bernard: The revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the Protestants in south-eastern France (Provence and Dauphiné) 1685-1730 . Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-56720-9 ( Paris historical studies 59).

- Chrystel Bernat (ed.): The camisards. A collection of essays on the history of the war in the Cevennes (1702–1710) . Publishing house of the German Huguenot Society, Bad Karlshafen 2003, ISBN 3-930481-16-2 ( history sheets of the German Huguenot Society eV 36).

- Henri Bosc: La guerre des Cévennes. 1702-1710 . 6 volumes. Presses du Languedoc, Montpellier 1985–1993, ISBN 2-85998-023-7 (extensive documentation of the uprising in the Cevennes).

- Philippe Joutard: Les camisards. Gallimard, Paris 1987, ISBN 2-07-029411-0 ( Collection archives 63).

- Robert Poujol: L'Abbé du Chaila (1648-1702). Bourreau ou martyr? You Siam aux Cevennes. Presses du Languedoc et al., Montpellier 1986, ISBN 2-86839-073-0 ( OEIL / Histoire ).

- Pierre Rolland: Dictionnaire des camisards. Presses du Languedoc, Montpellier 1995, ISBN 2-85998-147-0 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dirk Van der Cruysse: Madame is a great craft, Liselotte von der Pfalz. A German princess at the court of the Sun King. From the French by Inge Leipold. 14th edition, Piper, Munich 2015, ISBN 3-492-22141-6 , p. 337

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz , ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt / M., 1981, p. 222.

- ↑ Dirk Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft, Liselotte von der Pfalz , 2015, p. 336 and p. 581

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz , ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt / M., 1981, p. 127 (letter of September 23, 1699 to the Electress Sophie).