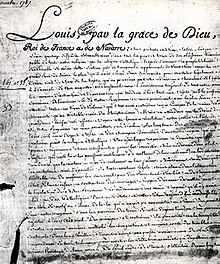

Edict of Versailles

The Edict of Versailles ( French Édit de Versailles ) was one of Louis XVI. On November 29, 1787, Edict of Tolerance in favor of the non-Catholic population groups. It brought the Huguenots in particular certain civil rights, but not the free exercise of religion or complete legal equality.

prehistory

Louis XIV had repealed the Edict of Nantes by the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685 . As a result, Catholicism was strengthened as the state religion, while the Calvinist practice was in fact forbidden. Those who refused to bow to this were persecuted. Many Huguenots converted to Catholicism under heavy pressure from the government. There was also massive emigration, especially to the Netherlands, Switzerland and some German territories. The emigration of skilled workers was accompanied by a weakening of the French economy. In the country itself, the Calvinist denomination could only survive in secret. In 1762 a Protestant pastor was sentenced to death for the last time.

In the course of the Enlightenment , the idea of religious tolerance towards minorities made progress. Voltaire was one of the first to publicly speak out in favor of tolerance in 1763. Various personalities such as Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, baron de l'Aulne , Guy-Jean-Baptiste Target , but in particular Chrétien-Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes and the spokesman for the Protestants still living in France, Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne , urged the to improve the legal situation of the Huguenots.

Even if the legal restrictions remained, the Protestants were tolerated in many places. In practice, the parliaments had already decided in the direction of religious tolerance, so the government only implemented this later. The reform policy of Étienne Charles de Loménie de Brienne in the pre-revolutionary period not only included tax and budget policy, but rather the legitimacy of the government depended on measures in as many policy areas as possible.

content

Rabaut had originally aimed to enforce full legal equality. Church services should also be allowed to be held in churches again. The exclusion of Protestants from all public office should come to an end. The king and his government did not want to go quite as far as some demanded. After all, the coronation oath included the eradication of heresy .

The text consisted of 37 articles. An appendix laid down the fees that the Huguenots had to pay Catholic pastors or state officials for certain services.

The key messages were: Art. 10: The Catholic religion remained the state religion. Art. 11: Public Protestant worship services remained prohibited. Art. 12: Protestants were not allowed to found any organizations representing them. In addition, the assets of emigrated Huguenots were confiscated. Penal laws directed against new converts, for example, also remained in place.

What was new was that Protestants registered marriages and deaths and thus legalized them. This could happen with the Catholic priests or with royal officials. It was now also possible to set up their own cemeteries. The Edict of Tolerance only granted recognition under civil law. Associated with this were property and inheritance law. Weddings could be closed and the descendants were legitimate and legally competent. Religious freedom and access to public office were not granted.

Compared to the Edict of Versailles, Joseph II's patent of tolerance from 1781 went significantly further. After all, the monarchy had to indirectly admit that the repeal of the Edict of Nantes had been a mistake.

Malesherbes intended that all non-Catholic populations should benefit from this policy. The imprecise formulation "apart from exceptions" was not applied to the Jews and Lutherans in administrative practice. Therefore, the edict primarily concerned the Calvinist Huguenots.

The edict was registered by parliament on January 29, 1788 and became legally binding. Complete legal equality occurred in the course of the French Revolution from 1789.

literature

- Eberhard Gresch: The Huguenots: History, Theology and Effect. Leipzig, 2005 p. 56

- Tolerance. In: Helmut Reinalter (Ed.): Lexicon on Enlightened Absolutism in Europe, Vienna a. a. 2005 pp. 613-615

- Anna Bernard: The revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the Protestants in south-east France 1685-1730. Munich, 2003 p. 156

- Simon Schama: The hesitant citizen. Step backwards and progress in the French Revolution. Munich 1989 p. 261