Parlement

The Parlement [ paʀləmɑ̃ ' ] was a judicial institution in medieval and pre-revolutionary France . The French word parlement (it is derived from parler , to speak 'and originally meant' speech, conversation, discussion ') has been used since the second half of the 13th century to refer specifically to the royal court sessions ( Latin curia regis , French la cour du roi or . la cour de parlement ). Around 1300 a permanent supreme court was established in Paris for appeals against the judgments of the Baillis and Seneschalle (royal court officials). This kept the name la cour de parlement , which was shortened more and more to le Parlement . The name was then also used for the twelve other supreme courts of the same type, which were later used in the individual provinces, e.g. B. in Rouen for Normandy , Rennes for Brittany , Toulouse for Languedoc , etc.

Difference Parlement vs. houses of Parliament

In German historiography, the convention has prevailed to translate the French word parlement with “parliament” even if it does not denote a legislative assembly in the current sense, but one of the supreme courts of justice of the time before 1789, i. H. of the Ancien Régime .

history

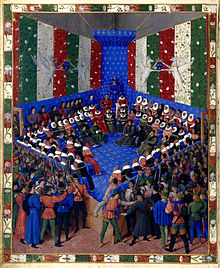

The early Capetians were in the habit of summoning their main vassals and the prelates of the kingdom to their court at regular intervals. These meetings took place on the occasion of one of the great festivals of the year in the city in which the king was currently residing. Here they pondered political affairs, and the vassals and prelates gave their advice to the king. But the monarch also tried cases brought before him. In the early days of the Capetian dynasty there weren't many, for the king always upheld the principle that he was only a judge with general and unlimited competence; at the same time, it was not compulsory to bring cases to the king. At that time there were no callings in the strict sense of the word. If a case was brought before the king, he still judged it with the help of the assembled prelates and vassals who made up his council. That was the royal council (lat. Curia regis , frz. Cour royale ). But by law the king was the only judge, while the vassals and prelates had only advisory functions. During the 12th and early 13th centuries , the curia regis continued to perform these functions, but its importance and real competence continued to grow. In addition, councils (lat. Consiliarius , plural consiliarii , frz. Conseiller (s) ) were added to the council, who belonged to the king's entourage and acted as his permanent and professional advisers. Under the government of Louis IX. , the saint who also marks the period in which the term Parlement appears for these sessions, things changed. The judicial competence of the parliament developed and was more clearly defined; the system of appeals was set up and appeals against the judgments of the Baillis and Seneschalle were brought before the Parliament. Cases concerning the royal cities, the bonnes villes , were also decided by him. The names of the same council members appear repeatedly in the old registers of the parliament from this time. This suggests that there was a sufficiently large list of potential councilors from whom some were selected for each meeting; the vassals and prelates still served as a complementary body.

Next came a series of ordinances that set the terms of office of the Parliament (1278, 1291, 1296, 1308) and it became more institutionalized. Not only were the persons who constituted the parliament in each case determined in advance, but those who had not been put on the list could not judge a case. The royal bailiffs had to attend the parliament to give reasons for their judgments, and the order in which the cases from the bailiages were heard was established at an early stage . Before the mid- 14th century , the parliamentary staff, both presidents and councilors, were de facto , if not de jure , determined by law. Each year a list of those who would hold the meetings was drawn up, and although the list was made annually, it contained the same names every year. The annual commissioners (French commissaires ) were 1,344 officials (French officiers ); they had permanent positions, but were not yet permanent. At the same time the parliament became permanent; the number of sessions had decreased but their length increased. During the 14th century it became a rule that the Parlement of St. Martin (November 11th) met until the end of May; later the session was extended to mid-August, while the rest of the year was vacation. In Paris, too, the parliament had become a permanent institution, and through a development that went back to fairly early times, the presidents and councilors had acquired certain positions of power instead of merely being advisors to the king, which were, however, bestowed by the monarch; they were, in fact, real magistrates . The king held court less and less in person; the parliament pronounced its judgments in the absence of the king. It even happened that he represented his case before the Parliament as a plaintiff or defendant. In the 14th century, however, it still happened that the parliament passed delicate matters on to the king; but in the 15th century it gained a basically independent jurisdiction. Regarding its composition, it retained a remarkable feature that is reminiscent of its origins: originally it was an assembly of lay vassals and prelates; When its structure became established and consisted of councilors, some of the offices were necessarily occupied by lay people and another by clergy, the lay advisors ( French conseillers lais ) and clerical advisers (conseillers clercs) .

Meeting of the Pairs

At the same time, the parliament was a meeting of the pairs (French cour des pairs ). This had its origin in the old principle according to which every vassal had the right to be tried by his pairs , i.e. H. from the feudal men who had received their feud from the same liege lord; these sat in court with the liege lord as president. As is known, this led to the formation of the old institution of the Pairs de France , which consisted of six lay people and six clergymen. But although feudal affairs were strictly to be judged by themselves, they could not uphold this right in the royal council (curia regis) . The other people in it could also participate in matters affecting the pairs. Finally, were French Pairs whose number by repeated creation of peerages by the king increased over time on its own initiative ( ex officio ) Members of Parlements; they became hereditary council members, swore the oath as official magistrates and sat and deliberated - if they wanted - in parliament. In proceedings which were brought against them or which concerned their rights as a pair, they had the right to a process by the parliament, with the other pairs being present or duly summoned.

Division of the parliament into chambers

While the Parliament maintained its unity, it had been divided into several chambers or sections. In the first place there was the "Great Chamber" (French la Grande Chambre or Grand 'Chambre ), which was the original Parliament. It had jurisdiction over certain important cases and it followed a special procedure known as oral, although certain written documents were allowed. Even after the offices of parliament had become available for sale, council members could only move from another chamber to the grand chambre in the order of seniority . The Chamber of Appeals (chambre des enquêtes) and the Chamber of Petitions (chambre des requêtes) came into being at the time when it became customary to draw up lists for each session of the Parliament.

The Chamber of Appeals - chambre des enquêtes

The investigators appointed by the Parliament (French: enquêteurs or auditeurs ) were initially auxiliary persons who were entrusted with the investigations and investigations ordered by the Parliament . But later, when the institution of appeal was fully developed and the proceedings in various jurisdictions became a highly technical matter (especially when written evidence was admitted), the documents from other inquiries also came before the Parliament. A new form of appeal emerged side by side with the older form, which was essentially an oral process, namely the written appeal (appel par écrit) . To evaluate these new appointments, the Parlement especially written documents had to study, the investigations under the jurisdiction of the first instance court had been made and written down. It was the duty of the investigators to summarize the written documents and prepare and report on them. Later the examiners (French rapporteurs ) were allowed to assess these questions together with a certain number of members of parliament, and from 1316 onwards these two types of members formed an appeal chamber (chambre des enquêtes) . Until now, the examiner had undoubtedly only given his opinion on the case he had been preparing. But after 1336 all members of the Chamber were put on the same level and reported and gave their judgments as a whole. For a long time, however, the Grande Chambre received all cases first and passed them on to the Appeals Chamber with instructions; questions arising from the appeals chamber's investigations were also discussed before her, and her decisions were put into effect or revised. But gradually it lost all these rights until they disappeared completely in the 16th century . Several chambers of appeal were created after the first, and it was they who did most of the work.

Chamber of Petitions - chambre des requêtes

The petitions chamber (chambre des requêtes) was of a completely different nature. At the beginning of the 14th century , some of the members of the parliament were excluded to receive petitions (requêtes) on judicial questions that had been submitted to the king and had not yet been dealt with. This eventually led to the formation of a chamber in the true sense of the word, the Chamber of Palace Petitions (Chambre des requêtes du palais) . However, this only became a court for privileged persons; to her (or to the Chamber of Petitions of the Royal Household, Chambre des requêtes de l'hôtel (du roi) , depending on the case) the civil proceedings of those who have the right to commit (Latin committere 'entrust' - regi et judici committimus causam nostram 'We entrust our case to the king and judge'), a right of direct jurisdiction before the king. Appeals against decisions of the Petitions Chamber could be brought before the actual parliament.

Criminal Chamber - chambre des assises

The parliament also had a criminal chamber, that of la Tournelle, which was only established in the 16th century but was active long before that. It had no specific membership, but the lay counselors (conseillers laics) served alternately in it.

Crime, Penalties, and Jurisdiction

The most common criminal acts were theft, burglary and fraud. The punishments ranged from reprimand, fines, jail, labor or penitentiary. On the other hand, robbery, manslaughter and murder were less common. Even under Philip IV , French criminal prosecution became more professional; in 1303 there was formal reference to the procureurs du roi and procureurs fiscaux de seigneurs . These institutions made it possible to prosecute swiftly, especially those crimes that were accompanied by fines and confiscations in favor of the ruling house. The Parliament was an institution of justice, under the Ancien Régime it was the sovereign court of the Kingdom of France.

The torture was considered a legitimate means of obtaining confessions or information from suspects considered. It was seen as an ideal way to obtain probatio probatissima proof in the event of difficult finding and as such it remained until the end of the Ancien Régime . This information could be used during the process. However, the information obtained by torture were only used as evidence, if evidence were exhausted in finding evidence or appeared.

The magic offense of witchcraft was only abolished as a criminal offense after the French Revolution . Nevertheless, Louis XIV , whose court was involved in the poison affair around 1680 , had already decided in the same year to object to the persecution with a decree. This largely put an end to the systematic and organized witch hunts in France. Although occasional persecutions took place as part of the magical offense, the last execution of a man for witchcraft took place in Bordeaux in 1718. In 1742, Father Bertrand Guillaudot and five other accused died at the stake in Dijon . They used magic, it is alleged, to predict the hiding place of a hidden treasure. Father Louis Debaraz was burned alive in Lyon in 1745 .

During the Ancien Régime there were different types of execution , such as beheading with the sword , see Charles Henri Sanson . The decapitation ( décollement ) was a privilege of the nobles, the death penalty for the commoners was hanging ( pendaison ) and was not considered honorable. But also, for example, the quartering became known as a crime against the state or its representatives, by Robert François Damiens on Monday, March 28, 1757, in Paris.

As a militarily organized police force, the Maréchaussée was the direct forerunner of the French Gendarmerie Nationale. Special units were also the Maréchausee of the Île de France (Compagnie du Prévôt Général de la Maréchaussée de l 'Ile-de-France) stationed in Paris, which monitored the Parisian suburbs and the surrounding area (banlieue), as well as the several hundred men strong company of the General Mint (Compagnie du Prévôt Général des Monnaies de France), which persecuted counterfeiters in particular.

In terms of effectiveness , the Paris police authorities were the leaders in Europe in the field of “foreign supervision”. Such was the control in the capital Paris in the age of Louis XV. and Louis XVI. very efficient. Denis Diderot described in a letter from 1760 to the Russian Tsarina Catherine II that in the Hôtel du lieutenant général de police they knew who they were, their names, where they came from and why, just twenty-four hours after the arrival of a foreigner he was in France, where he lived and with whom he was in contact.

Provincial Parliaments

Originally there was only one parliament, that of Paris. That was a logical consequence of the emergence of the curia regis. But the requirements of the administration of justice gradually led to the creation of a number of provincial parliaments. Their establishment was also generally dictated by political circumstances, particularly after the accession of a province into the kingdom. Sometimes it was a province which, prior to its annexation, had a supreme and sovereign jurisdiction for itself and which was to keep this privilege. It happened that between the annexation of a province and the establishment of its parliament an interim system was set up in which delegates of the Paris parliament went there and held court sessions (assisen, assises ). In this way, the parliaments of Toulouse , Grenoble , Bordeaux , Dijon , Rouen , Aix-en-Provence , Rennes , Pau , Metz , Douai , Besançon and Nancy were created one after the other . From 1762 to 1771 there was even a parliament for the principality of Dombes . The provincial parliaments replicated the organization of the Paris parliament on a smaller scale; but they did not have the functions of the court of pairs. Each of them claimed equal power in their respective province. There were also large judicial bodies who exercised the same functions as the Parlements, but without bearing their names, for example, the "Supreme Council" (Conseil souverain) of Alsace in Colmar , the "Upper Council" (Conseil supérieur) of Roussillon in Perpignan ; the “Council of Artois” (Conseil de l'Artois) did not have the highest jurisdiction in every respect.

Political rights

Apart from their judicial functions, the parliaments also had political rights; they claimed participation in the higher politics of the kingdom, and the position of guardians of its fundamental laws. In general, the laws in the provinces did not come into force until they were registered by the parliaments. This was the method of publicity allowed by the old law in France. However, the parliaments examined the laws before they registered them, i. that is, they examined them to see whether they conformed with the principles of law and justice and with the interests of the king and his subjects; if they felt this was not the case, they refused to register and raised remontrances to the king. In doing so, they were merely complying with their duty of advice (devoir de conseil) , which all higher authorities had vis-à-vis the king, and the text of the ordinances often explicitly asked them to do so. It was natural, however, that the king's will should prevail in the end. To register z. B. to enforce edicts, the king sent sealed order letters (lettres de jussion) , which were not always followed, or he could come in person and hold a parliamentary session and the law in his presence in a so-called bed of justice ( Lit de justice) . Theoretically, this was explained by the principle that if the king as chief judge personally pronounced justice, the court lost all authority delegated by him through the fact of his presence, just as there had been in the old curia the principle that “apparente rege cessat magistratus ”(Latin for“ When the king appears, the magistrate is silent ”(as judge )). In the 18th century , the opinion developed in the parliaments that the registration of a law by them had to be done voluntarily, a lit de justice , i.e. an unfriendly act if it was not illegitimate.

Administrative rights

The parliaments also had extensive administrative powers. They had the right to make regulations (pouvoir réglementaire) which, within their province, had the effect of laws in all such points that were not already regulated by law, insofar as the matter in question fell within their judicial competence; all that was necessary was that their interference in the matter was not prohibited by law. These determinations were called arrêtés de règlement .

It was by these means that the parliaments participated in government, except in matters assigned to another supreme court; for example, taxation was the responsibility of the “highest tax courts” (French: Cours des aides ). Within the same restrictions, they could issue injunctions to officials and individuals.

See also

literature

- Sylvie Daubresse: Le parlement de Paris ou la voix de la raison. (1559–1589) (= Travaux d'humanisme et renaissance. Vol. 398). Droz, Genève 2005, ISBN 2-600-00988-4 .

- Sylvie Daubresse, Monique Morgat-Bonnet, Isabelle Storez-Brancourt: Le parlement en exil, ou, histoire politique et judiciaire des translations du Parlement de Paris (XVe - XVIIIe siècle) (= Histoire et archives. Hors-série No. 8), Champion, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-7453-1681-3 .

- Roland Delachenal: Histoire des avocats au parlement de Paris. 1300-1600. Plon, Paris 1885.

- James K. Farge: Le parti conservateur au XVIe siècle. Université et parlement de Paris à l'époque de la Renaissance et de la Réforme. Collège de France et al., Paris 1992, ISBN 2-7226-0000-5 .

- Édouard Maugis: Histoire du parlement de Paris. De l'avènement des rois Valois à la mort d'Henri IV. 3 volumes. Picard, Paris 1913-1916;

- Volume 1: Période des rois Valois. 1913;

- Volume 2: Période des guerres de religion de la ligue et de Henri IV. 1914;

- Volume 3: Rôle de la cour par règnes, 1345–1610, (présidents, conseillers, gens du Roi). 1916.

- William Monter: Judging the French Reformation. Heresy trials by sixteenth-century parlements. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA et al. 1999, ISBN 0-674-48860-1 .

- Nancy Lyman Roelker: One king, one faith. The Parlement of Paris and the religious reformations of the sixteenth century. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 1996, ISBN 0-520-08626-0 .

- Lothar Schilling: Norm setting in the crisis. On the understanding of legislation in France during the wars of religion (= studies on European legal history. Vol. 197). Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-465-03454-6 (also: Cologne, University, habilitation paper, 2003).

- Joseph H. Shennan : The Parlement of Paris. Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY 1968.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lorenz Schulz: Standardized distrust. The suspicion in criminal proceedings. Klostermann (2001) ISBN 3-465-02973-9 , p. 203

- ↑ Gerhard Sälter: police and social order in Paris: On the origin and enforcement of standards in everyday urban life of the Ancien Regime (1697 to 1715). Klostermann (2004) ISBN 3-4650-3298-5

- ↑ Eric Wenzel: La torture judiciaire dans la France de l'Ancien Régime: Lumières sur la Question. Editions Universitaires de Dijon, 2011, ISBN 978-2-915611-89-2 .

- ↑ Johannes Dillinger: Witches and Magic: a historical introduction. Campus Verlag, 2007, ISBN 3-593-38302-0 .

- ^ Henry Charles Lea: Materials Toward a History of Witchcraft 1890. Volume 3 Kessinger Publishing, 2004 p. 1305

- ↑ Cie de Maréchaussée de l'Ile-de-France , in French, online