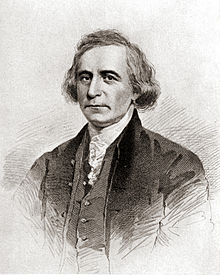

Philip Freneau

Philip Morin Freneau (born January 2, 1752 in New York ; died December 18, 1832 in Middletown Point, now part of Matawan , New Jersey ) was an American poet . At the time of American independence movement , he acquired with patriotic poems the reputation of the "poet of the American Revolution." In the early years of the Republic, he joined as a propagandist of journalistic work with the Republican Party to Thomas Jefferson produced. While Freneau's political works received the most attention during his lifetime, some natural and grave poems such as The Wild Honey Suckle , To a Caty-Did, and The Indian Burying Ground are now considered to be his most important contribution to American literary history; they point beyond contemporary neoclassicism and make Freneau appear as a forerunner of American romanticism .

Life

Origin and youth

Philip Freneau, born January 2, 1752 in New York, was the eldest of Pierre and Agnes Freneau's five children. His father came from a Huguenot family who had settled in New York in 1709 and built up a brisk wine trade with France and Madeira , his mother came from a family of Scottish Presbyterians settling in New Jersey. Shortly after he was born, his parents settled in Monmouth County , New Jersey, and built the Mount Pleasant family residence near the present-day town of Matawan , where Freneau would spend much of his life.

Little is known about Freneau's early years, but it is believed that he first attended boarding school in New York. From 1766 he studied under Presbyterian clergy, first with the Rev. William Tennent, from 1766 then at the Latin School of Monmouth under the Rev. Alexander Mitchell. Apparently his deeply religious parents expected him to pursue a career as a priest.

In 1768 he enrolled at the College of New Jersey , now Princeton University . Because of his previous education at the Monmouth Latin School, he was able to skip the first year of study. At that time, under Dean John Witherspoon, the university developed into one of the most educationally advanced, but also politically radical universities in America; many leading figures of the American independence movement and the early republic emerged from it, for example in the graduating class of only thirteen in 1771 alongside Freneau James Madison , Gunning Bedford, Jr. and Hugh Henry Brackenridge , in the class of 1772 also Aaron Ogden , Henry Lee , William Bradford and Aaron Burr . During his student days, Freneau had a close friendship, especially with Brackenridge, with whom he co-authored some of his early works, such as the epic poem The Rising Glory of America , which they read out on the occasion of their graduation in 1771. Freneau himself was not present at the public reading; his father's death had put his family in financial trouble and he had had to go to Mount Pleasant to organize the auction of parts of the property.

Revolution time

In 1772 Freneau's first volume of poetry, The American Village, was published, and in the same year he took up a position as a teacher in Flushing on Long Island. But he left this post after a short time, because his pupils seemed too stupid to him: Long Island I have bid adieu / With all its brutish, brainless crew / The youth of that detested place / Are void of reason and of grace he wrote in one Letter to Madison. Towards the end of the year he tried his luck once more as an assistant teacher at Brackenridge's side at Somerset Academy in Princess Anne, Maryland , but developed such an aversion to the profession that he vowed never to teach again. Little is known about his activities between 1772 and 1775. He probably traveled a lot through the American colonies and was apparently still considering going to England in 1773 to train and ordain a priest, but a year later he wrote that theology, the “study of Nothing ”, don't accept.

The political mood, heated up by the increasing tensions between the English motherland and the American colonies, does not seem to have impressed Freneau, at least until 1775. In that year he published several satirical verses, the target of which was the British General Thomas Gage in particular . However, he did not experience the further escalation of the American Revolution, the Declaration of Independence and the outbreak of the War of Independence: In 1775 he settled in the Danish colony of Saint Croix in the Caribbean. What prompted Freneau - later glorified as the “poet of the American Revolution” - to take this step has puzzled all his biographers. He spent the next three years mainly on Saint Croix, which seemed to him a paradise on earth, but also visited other islands, including the British colonies Jamaica and Bermuda.

Not until 1778 did he return and join the revolutionary militia of New Jersey, where he made it to sergeant . He also put his poetry at the service of the independence movement: he published the poem America Independent and became one of the most productive authors of the patriotically minded United States Magazine , which his friend Brackenridge founded in Philadelphia in August 1778. In 1779 he left New Jersey again and embarked for the Azores; but since his ship was being pursued by the British, it had to change its course, so that Freneau finally landed on the Canary Island of La Palma in the port city of Santa Cruz, where he spent two months in 1779. After his return to America he bought a letter of credit for his sloop Aurora and was thus able to build up a private Caribbean trade and drive coastal patrols for the revolutionary troops. In May 1780, however, the aurora in Chesapeake Bay was applied by an English ship and Freneau and his crew were arrested. He was transferred to one of the notorious prison ships in New York harbor, where thousands of prisoners were killed in inhumane conditions. Freneau also suffered from illness and malnutrition during his six weeks in prison, was transferred to a hospital ship and finally released in July on the condition not to rejoin the revolutionary forces. He made his time on the prison ship the subject of his most famous poem of the revolutionary era. The British Prison Ship , published in 1781, described the suffering of the prisoners with such depressing urgency that the poem also offered itself as anti- British propaganda and was reprinted many times on leaflets. The traumatic experiences on board the prison ships may have contributed to the darkening of his worldview - while youthful enthusiasm, pastoral or escapist fantasies shaped his early poems, the awareness of the vain appearance of everything worldly is the tenor of his further works.

Journalistic activity in the early republic

Upon his release, he settled in Philadelphia where he became editor of Francis Bailey's Freeman’s Journal or North American Intelligencer . Up to June 1784 Freneau accompanied the further course of the revolution up to the peace of Paris and beyond with poems and essays. At least as much as the British themselves, the American loyalist press, which was mostly based in the still British-controlled New York, was now the target of his attacks. In political articles, essays and occasional poems, he took a stand on the small and big political questions of the republic, spoke out against slavery and for more women's rights and thus distinguished himself as an egalitarian-minded publicist, often radically ostracized by his opponents.

In 1784, Freneau left the paper, perhaps because the attacks of his opponents were getting sharper and more personal, bought a brig and tried again as a ship's captain. Over the next few years he ran a bustling Caribbean trade, but also found time to write new poems - many of them about seafaring - so that they could be published immediately on every trip home in New York or in Charleston, where his brother Peter Freneau wrote the City Gazette issued to deliver. In 1786 and 1788 he published two volumes of poetry, for which he mainly edited earlier poems and in some cases significantly changed them, but also wrote a few new poems. After his marriage in 1790, under the pressure of his bride, he gave up his life at sea, moved to New York in the spring of 1790 and took over the management of the Daily Advertiser newspaper for a year .

From 1791 he let his talent for the political goals of the anti-federalists around Madison and Thomas Jefferson harness. When the federal government moved from New York to Philadelphia in 1790, Jefferson, in his role as Secretary of State, initially gave him a well-paid job at the State Department as a translator from French into English. To counter the Gazette of the United States , the mouthpiece of the federalist party around President Washington's Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton , Jefferson and Freneau's college friend James Madison sought to found a newspaper the following year. Freneau acted as the editor of the National Gazette entitled sheet, which appeared for the first time on October 31, 1791. In his own political commentaries, satires , essays and poems, he commented on national and international politics, with reporting on the French Revolution deserving special attention. As a staunch Republican and - by birth - Francophile, Freneau took part in the radicalization of the revolution in articles and poems such as On the Anniversary of the Storming of the Bastile and The Demolition of French Monarchy . He printed the constitution of 1791 in full, two years later with obvious amusement Brackenridge's bon mot on the beheading of Louis XVI. : "Louis Capet has lost his Caput. “ He may also have been the author of the four articles published in the National Gazette under the pseudonym Veritas , which sharply castigated Washington’s proclamation of neutrality in the coalition war as treason against France. In the summer of that year he even made a stand for the French ambassador, " Citizen Genet ", when his agitation against American neutrality in the coalition wars and for the establishment of American Jacobin clubs was rejected by Jefferson himself.

With polemical attacks, especially on Hamilton, Freneau soon acquired the reputation of a harlot. Hamilton read every issue of the National Gazette himself to find out what new misdeeds Freneau accused him of, and saw himself as the victim of a concerted character assassination campaign: The State Department paid Freneau to “sow resistance to government decisions and to promote public peace with false allegations to disturb". The fact that Freneau was employed by a government agency struck him as outrageous: "It is ungrateful for someone to bite the hand that feeds you, but if you get paid to do it, the case changes." The rivalry between Jefferson and Hamilton escalated 1792–93, as a Hamilton biographer writes, when the two began to hunt each other with "journalistic bloodhounds" - Freneau on the one hand, John Fenno on the other. Hamilton himself launched several anonymous or pseudonymized articles in the United States Gazette, in which he exposed Freneau's employment at Jefferson's State Department and castigated not only as nepotism, but as sabotage. In another article, he painted a picture of Jefferson and Freneau in shrill tones, as they mix the “poison” together in a quiet little room , which they then circulate through the National Gazette . Freneau was also not afraid to criticize the president with unprecedented severity. Freneau repeatedly accused Washington of monarchical airs, especially on the occasion of the large-scale celebrations for his 61st birthday. When Freneau once accused him of "monarchical narrow-mindedness," Washington spent an entire cabinet meeting raging over "that scoundrel Freneau" (that rascal Freneau) and asked Jefferson to dismiss Freneau, which Freneau was able to postpone. It was not until the end of Jefferson's tenure towards the end of 1793 that the patronage, which Freneau had enjoyed until then, ended, and the National Gazette was closed in October of that year. Jefferson later expressed the view that Freneau had "saved the Constitution by the time it galloped quickly towards the monarchy".

Late years

With the suspension of the National Gazette , Freneau retired to the Mount Pleasant family estate. In 1794 he self-published an almanac there, in 1795 he himself printed an expanded and in many places revised edition of his poems and founded the Jersey Chronicle. In the only one year of its existence, the paper braced itself against the ratification of the Jay Treaty , which Freneau and Jefferson saw as a betrayal of elementary American interests to the British. After just under a year, Freneau shut down the newspaper when the political turmoil subsided. A year later, alongside Matthew L. Davis, he became co-editor of the New York magazine The Time Piece, and Literary Companion, which until then had primarily been a literary magazine, but within a few months of being the editor, Time Piece also became an increasingly political one Blatt, whose lines Freneau in turn used to continue his personal feud with federalist publicists like John Fenno - also in poetry. In the Jersey Chronicle and Time Piece he also published essays on social issues, some of which are hidden behind various personas such as "Tomo Cheeki", an Indian who, through his outsider perspective, gives an ironically broken impression of the running of the republic. One of his essays turns against the legal practice of culpable imprisonment - which Freneau struggled to escape even in the winter of 1797 - the loss of his sloop Aurora in the war was a loss from which he never recovered. After a change of ownership of the magazine, Freneau gave up his editing position in March 1798 and thus ended his journalistic career.

First he moved with his family - from his marriage had four daughters - again to Mount Pleasant. He continued to work the estate with slaves, despite his early and frequent comments about the illegality of slavery. However, he is said to have finally released his slaves of his own free will after New Jersey adopted a law to gradually abolish slavery in 1804. In 1802 he and his brother Pierre bought a brig, the Washington , and again sailed the North Atlantic for years. He did not visit Europe, but docked in the Canaries and Madeira. His hopes to continue his family's traditional Madeira trade were dashed. In order to pay off his debts, he had to sell more and more properties around his property over the years; In 1818 the house also burned down, so that he retreated to the small farm of his late in-laws on the outskirts of Freehold, New Jersey, and became increasingly impoverished. His last signature is on the petition for a veteran's pension of $ 35 annually. It was granted, but before the first payment was made, Philipp Freneau froze to death in a snow storm on the night of December 18, 1832 on the way back to his farm.

Work and reception

Until well into the twentieth century, the evaluation of Freneau's work and personality in literary historiography was determined by the ideological rift that lingered in American intellectual history long after the fall of the federalists and antifederalists. He was treated with abuse by the numerous authors who glorified Washington's reign and style as the standard and ideal of the republic, for example by Freneau's contemporaries Timothy Dwight , later by Washington Irving , who named Freneau in his monumental Washington biography "Yapping mutt" called Jeffersons. Even Moses Coit Tyler characterized Freneau primarily as a "poet of hatred, not of love", who in his verses fought for the revolution with "dogged, relentless, deadly warfare". Vernon Louis Parrington , whose Main Currents in American Thought (1927–30) is shaped by the spirit of Jeffersonian egalitarianism, made an attempt to reverse this judgment :

“In his Republicanism, Freneau was way ahead of the Federalists. He was a democrat while they remained aristocrats. He got rid of old prejudices, heir to an obsolete past in which they were still trapped. He recognized the importance of the movement towards decentralization, which would create a new way of thinking and ultimately democratic individualism. He did not stand in the way of this development; he accepted them in all their consequences. He freed his mind from the bondage of the caste system; he was not driven by a selfish desire to impose his will on others. [...] Like Paine, he distrusted any form of concentration of power. Like Franklin, he found everyday political and economic business absurd, indifferent to justice, and did what he could to change it. As he stood up for the cause of democracy, he promoted a number of lesser causes: unitarianism, deism, abolitionism, the Americanization of education, and thus turned against him the social, religious, political, and social conservatives who were in America at the time flourished. Nonetheless, he went his way through this shabby world full of politicians and speculators, nourishing himself on every shade of beauty he met, a dreamer and an idealist, mocked by the exploiters, a spirit touched by higher than his generation. "

While these critics were primarily concerned with Freneau's convictions, his literary qualities received little or only superficial attention for a long time. His revolutionary and war poems, on which his fame was based during his lifetime, were recognized as effective propaganda by his political opponents, but they were often denied their literary value. Henry Adams , for example, wrote that in the early republic the USA had at least one poet with him who displayed “the delicacy, if not the greatness of a genius”, but also that his pen was more bad as good verses escaped. This tenor also shaped the judgment of literary studies well into the 20th century; the standard Freneau biography, Lewis Learys That Rascal Freneau (1942), has the telling subtitle A Study in Literary Failure ("Study of a literary failure"). This negative judgment is based on the fact that a large part of Freneau's oeuvre, as occasional poetry, is dependent on the circumstances of its creation and requires a good knowledge of the contemporary context in order to understand it. However, since Leary, literary critics have attested the timelessness and universality required of “real” poetry to a handful of natural and grave poems, the tone and subject matter of which are close to poets of English sensibility such as Thomas Gray , Edward Young and Hugh Blair , and Freneau as the forerunner of American Romanticism in particular The Vernal Ague, The Indian Burying Ground, The Dying Indian, The Wild Honey Suckle and To a Caty-Did.

Early work

Even in his student years, Freneau was a very productive poet: he joined forces with Madison, Brackenridge, and others in the student Whig Society , contrary to their name less a political than a literary club. In the semester 1770 to 1771 in particular, its members waged a lively penal war with the other student association on campus, the Cliosophic Society. A notable product of this feud was the picaresque prose piece Father Bombo's Pilgrimage to Mecca, co-authored by Freneau and Brackenridge . It is one of the earliest fictional prose works written in the colonies; at least one critic has even wanted to recognize Father Bombo as the first American novel - this “title” is usually given to William Hill Brown's The Power of Sympathy (1789).

Another highly acclaimed collaborative effort is The Rising Glory of America , a long dramatic poem in blank verse in which the bright future of America through the development of agriculture and trade on the one hand, and territorial expansion on the other, is portrayed in the tradition of Freneau's lifetime Millenarian ideas stand in which America appears as a promised land, which has a special role in salvation history :

A Canaan here,

Another Canaan shall excel the old,

And from a fairer Pisgah's top be seen.

No thistle here, nor thorn, nor briar shall spring,

Earth's curse before: The lion and the lamb,

In mutual friendship link'd, shall browse the shrub,

- [...]

Such days the world,

And such, AMERICA, thou first shalt have,

When ages, yet to come, have run their round,

And future years of bliss alone remain.

Kenneth Silverman even named this motif of American literature, which dates back to the Puritans of New England and which reappeared in a less religious guise during the Revolution, after Freneau's poem as the Rising Glory motif - it can be found, for example, in John Trumbull's Prospect of the Future Glory of America or Timothy Dwights America (1770). In the first version from 1772, the poem by Freneau and Brackenridge is not yet a prophecy of the splendor of the republic - the new continent is still being discovered and subjugated here by “Britannia's sons” (Britain's sons shall spread / Dominion to the north and south and west / Far from the Atlantic to Pacific shores) . In particular in comparison to the unfair motives of the papist, haughty and cruel Spaniards (a classic formulation of the " Black Legend ") and French (Gallia's hostile sons) , the British colonization of America in The Rising Glory appears to be borne by the forces of reason and progress Civilization project for the pious of the whole world:

Better these northern realms deserve our song,

Discover'd by Britannia for her sons;

Undeluged with seas of Indian blood,

Which cruel Spain on southern regions spilt;

To gain by terrors what he gen'rous breast

wins by fair treaty, conquers without blood.

It was only in the volume The Poems of Philip Freneau , published in 1786, that the now mostly anthologized version is found, in which all benevolent references to the motherland have been deleted and the role of the savior has been transferred to the now independent American nation in a new translatio imperii . Noteworthy in this context are the strategies that Freneau's poem uses to justify the submission of the indigenous people. If he had deplored the subjugation of the South and Central American Indians by the greedy Spaniards because they - as alleged descendants of the Carthaginians - had created a high culture themselves, the Indians of North America had hardly been able to rise to a corresponding level of civilization:

But here, amid this northern dark domain

No towns were seen to rise.

No arts were here;

The tribes unskill'd to raise the lofty mast,

Or force the daring prow thro 'adverse waves,

Gaz'd on the pregnant soil,

and crav'd alone Life from the unaided genius of the ground,

This indicates they were a different race ;

From whom descended 'tis not ours to say.

A year after graduating from college, Freneaus published his first volume of poetry. The title poem poem The American Village is an American answer to Oliver Goldsmith's The Deserted Village, the structure is based on Pope's Windsor Forest , but the location is relocated to the banks of the Hudson River. Here, too, the juxtaposition of the decaying villages of Europe and the young, up-and-coming settlements of the New World clearly shows the idea of history progressing westward . This transfiguration of a rural American idyll into paradise on earth (a place of ev'ry joy and ev'ry bliss) is also an early example of pastoralism , which has often been described as a myth pervading the entire American literary history, particularly with reference to Jefferson's “agrarian” ideal of a free peasant state. This notion is particularly evident in Freneau's work in the Epistle to the Patriotic Farmer, published in 1815 , in which it is said that it was the American farmer who "first aimed his spear at George's crown " (who first aimed a shaft at George's crown, / And marked the way to conquest and renown) .

Revolutionary and war poetry, newspaper verses

With the escalation of tensions between the American colonists and the English motherland, this love of homeland, previously formulated mythically, took on a concrete political expression. The earliest of the long series of explicitly political poems in Freneau's work, The New Liberty Pole, was written in early 1775 and legitimized an armed uprising against the despotism of the colonial rulers:

Though we respect the Powers that be,

And hold him an non-entity,

Who would not stir in our good cause

And rise to spurn despotic wars.

With the outbreak of the War of Independence , Freneau then sided completely with the separatists and republicans; for example, his “political litany” ( A Political Litany , 1775) begins with the words

Libera nos, Domine — Deliver us, O Lord,

Not only from British dependence, but also,

From a junto that labor for absolute power,

Freneau accompanied the further course of the war with occasional poems about battles and political events, for example in 1775 with a whole series of satirical poems in which he ridiculed the British General Thomas Gage ( General Gage's Soliloquy; Reflections on Gage's Letter to Gen. Washington's Letter of Aug. 13; General Gage's Confession and others). However, this series was interrupted by Freneau's break on the West Indies - the works created at this time, including escapist daydreams such as The Beauties of Santa Cruz , can at best be associated with current affairs as an expression of Freneau's annoyance with war. After his return to New Jersey in 1778, however, he put his poetry in the service of the revolution with undiminished enthusiasm. Until the peace treaty in 1783 he commented on the course of the war in poems such as On the Fall of General Earl Cornwallis, On THE MEMORABLE VICTORY, Obtained by the gallant Captain Paul Jones and Verses Occasioned by General Washington's arrival in Philadelphia, on his way to his seat in Virginia and in 1782 also wrote his only drama work (The Spy) about the betrayal of Benedict Arnold , which, however, remained unfinished.

The British Prison Ship, Freneau's poetic testimony to his time in British captivity, was particularly effective as revolutionary propaganda. This poem is divided into three sections; the first describes the incident in which Freneau's ship was arrested and the crew arrested, the second the three-week imprisonment on board the Scipio, the third then Freneau's time on the hospital ship. There are consistently strong anti-British tones, the British - and their Hessian mercenaries - are repeatedly reviled as brutes, monsters and devils. The poem unfolds its effect particularly through the listing of the hardships and atrocities to which the prisoners are exposed, crammed into hundreds without light, forced every morning to bury their fellow prisoners, who died in the night, in the sand:

But such a train of endless woes abound

So many mischiefs in these hulks are found

That on them all a poem to prolong

Would swell too high the horrors of our song.

Hunger and thirst to work our woe combine,

And moldy bread, and flesh of rotten swine;

The mangled carcase and the battered brain;

The doctor's poison, and the captain's cane;

The soldier's musquet, and the steward's debt:

The evening shackle, and the noonday threat.

Freneau calls his countrymen to arms to avenge the atrocities of war and drive the British out of the country:

Americans! a just resentment shew,

And glut revenge on this detested foe;

While the warm blood exults the glowing vein

Still shall resentment in your bosoms reign,

- [...]

Death has no charms, except in British eyes,

See, arm'd for death, the infernal miscreants rise,

See how they pant to stain the world with gore,

And millions murder'd, still would murder more;

This selfish race, from all the world disjoin'd,

Perpetual discord spread throughout mankind,

Aim to extend their empire o'er the ball,

Subject, destroy, absorb, and conquer all,

As if the power that form'd us did condemn

All other nations to be slaves to them -

Rouse from your sleep, and crush the thievish band,

defeat, destroy, and sweep them from the land

Even after the peace treaty of 1783, Freneau's productivity did not decline, especially since as the editor of his newspapers and almanacs he now had almost unlimited opportunities for publication. He fought spring wars first with the Tory press, particularly with the printer James Rivington , then in the 1790s with the federal press and commented on domestic and foreign policy (On the Death of Catherine II; On the Prospect of a Revolution in France ) . In the vast number of its newspaper and almanac verses but also find rhymes about the benefits of tobacco smoking (The Virtue of Tobacco) , exhortations to the ladies, regularly going to the dentist (Advice to the Ladies not to neglect the Dentist) , on the Tierwelt (Adress to a Learned Pig; On Finding A Terrapin in the Woods, Which had AD 1756 Marked on the Back of his Shell) , Gedichte über seine Hund (To the Dog Sancho, on his being Wounded in the Head with a Saber, in a midnight Assault and Robbery, near the Neversink Hills, 1778) , Elegies (On The Death Of Dr. Benjamin Franklin) , Poems against the felling of trees in the streets of New York (LINES, Occasioned by a Law passed by the Corporation of New-York, early in 1790, for cutting down the trees in the streets of that city) , against slavery (To Sir Toby) and against the displacement and disenfranchisement of the Indians (On the Civilization of the West Aboriginal Country) . If these poems in their entirety give an interesting moral picture of the time, they brought Freneau the reproach, which continues to this day, of being a mere “prolific writer”.

Natural poems

Some of Freneau's early poems contain descriptions of nature, but here nature is at best the scene of human activity, not the subject of poetry. The “cosmic riddle” of becoming, being and dying determined his work from the beginning, but after his experiences on the British prison ship, his worldview, which had previously been shaped by youthful confidence and belief in progress, darkened and gave way to “brooding over the brevity of life and the Certainty of death ”. This tenor - Freneau's master thought , as Harry Hayden Clark called him - shaped the poems that were written between 1784 and 1790, when Freneau left the press skirmishes in Philadelphia and sailed the Atlantic as a ship's captain. Richard Vitzthum sees the sea and seafaring poems that were written during this time as central to Freneau's work: in them the unfathomable sea, and therefore nature, is made clear in a previously unattainable intensity. Freneaus saw the sea not only as a symbol, but as a concrete threat. In 1784 he got into a hurricane with his ship off Jamaica and processed this life-threatening experience in a poem, Verses, Made at Sea, in a Heavy Gale, today often printed under the catchy title The Hurricane . It closes with two stanzas that lead from the immediate situation of the sailors delivered to the storm to a metaphysical reflection on death:

While o'er the dark abyss we roam,

Perhaps, whate'er the pilots say,

We saw the Sun descend in gloom,

No more to see his rising ray,

But bury'd low, by far too deep,

On coral beds, unpitied, sleep!

But what a strange, uncoasted strand

Is that, where death permits no day-

No charts have we to mark that land,

No compass to direct that way-

What pilot shall explore that realm,

What new Columbus take the helm.

In Freneau's poem, The Wild Honey Suckle , which is probably the most anthologized today , the observation of a natural phenomenon - the blossom of a honeysuckle hidden in the forest - leads to a similarly melancholy, if not nihilistic, thought:

From morning suns and evening dews

At first thy little being came:

If nothing once, you nothing lose,

For when you die you are the same;

The space between, is but an hour, the

frail duration of a flower.

It is obvious to read the flower as a symbol for human existence - just as it fades in the autumn frost and will finally disappear, our life is short, ephemeral, ultimately without consequences and void. Apart from this simple simile, the poem expresses above all the inability of the poet or the impossibility of grasping the essence of nature in general: the flower, according to Vitzthum, “exists in a non-human, non-feeling, non-knowing sphere in which Things come and go without meaning. Everywhere it is the gap between the poet's concern for the flower and the flower's indifference to the poet that emphasizes the poem. ” The Caty-Did also deals with the supposed“ messages ”of nature , an ode to onomatopoeic sound American grasshopper named for its chirping :

While upon a leaf you tread,

Or repose your little head,

On your sheet of shadows laid,

All the day you nothing said:

Half the night your cheery tongue

Revell'd out its little song,

Nothing else but Caty-did.

From your lodgings on the leaf

Did you utter joy or grief—?

Did you only mean to say,

I have had my summer's day,

And am passing, soon, away

To the grave of Caty-did: -

Poor, unhappy Caty-did!

Like the blossom in the forest, the grasshopper must leave this world with the coming and going of the seasons, into an uncertain hereafter:

Nature, when she form'd you, said,

"Independent you are made,

My dear little Caty-did:

Soon yourself must disappear

With the verdure of the year,

And to go, we know not where,

With your song of Caty- did. "

The insistence on the "illegibility" of nature makes Freneau's view of nature related to that of the "dark" American romantics like Herman Melville ; In particular, The Caty-Did anticipates Frederick Goddard Tuckerman's The Cricket (around 1860) in his metaphor , which also poetizes this fundamental epistemological doubt in the view of a grasshopper. According to his biographer Lewis Leary, who noted elsewhere that Freneau "failed in almost everything he tried," The Caty-Did is the poem that justifies Freneau's title as a poet. As a poet, Freneau wanted to be remembered by posterity (with a few exceptions, he barely had his prose works from newspaper articles reprinted), even if he lamented this calling in old age with characteristic irony: To write was my sad destiny / The worst of trades, we all agree.

literature

Works

Publications during his lifetime

A large part of Freneau's poems, such as his prose works and political works, first appeared in various American magazines, and some poems were also printed on leaflets. The following volumes of poetry were published as individual prints (volumes and leaflets):

- A Poem, on the Rising Glory of America. Joseph Crukshank, Philadelphia 1772.

- The American Village, a Poem. S. Insley & A. Carr, New York 1772.

- The British Prison-Ship: A Poem. Francis Bailey, Philadelphia 1781.

- The Poems of Philip Freneau Francis Bailey, Philadelphia 1786.

- A Journey from Philadelphia to New York. Francis Bailey, Philadelphia 1787.

- The Miscellaneous Works of Mr. Philip Freneau. Francis Bailey, Philadelphia 1788.

- Poems Written between the Years 1768 & 1794. Philip Freneau, Monmouth 1795. archive.org

- Letters on various interesting and important subjects. D. Hogan, Philadelphia 1799.

- Poems written and published during the American Revolutionary War. 2 volumes. Lydia R. Bailey, Philadelphia 1809

- A Collection of Poems, on American Affairs. 2 volumes. David Longworth, New York 1815.

Modern factory editions

- Fred Lewis Pattee (Ed.): The Poems of Philip Freneau. 3 volumes. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1902-1907.

- Digitized at the Internet Archive : Volume 1 ; Volume 2 ; Volume 3

- Harry Hayden Clark (Ed.): Poems of Freneau. Harcourt Brace, New York 1929.

- Charles F. Heartman: Unpublished Freneauana. New York 1918.

- Lewis Leary (Ed.): The Last Poems of Philip Freneau. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ 1945.

- Philip M. Marsh (Ed.): The Prose Works of Philip Freneau. Scarecrow Press, New Brunswick, NJ 1955.

- Judith A. Hiltner: The Newspaper Verse of Philip Freneau: An Edition and Bibliographical Survey. Whitston, Troy 1986.

Secondary literature

- Nelson F. Adkins : Philip Freneau and the Cosmic Enigma: The Religious and Philosophical Speculations of an American Poet. New York University Press, New York 1949.

- Robert D. Arner: Neoclassicism and Romanticism: A Reading of Freneau's "The Wild Honey Suckle". In: Early American Literature 9: 1, 1974.

- Mary S. Austin: Philip Freneau, the Poet of the Revolution: A History of his Life and Times. A. Wessels, New York 1901. archive.org

- Jacob Axelrad: Philip Freneau: Champion of Democracy. University of Texas Press, Austin 1967.

- Mary Weatherspoon Bowden: Philip Freneau . Twayne, Boston 1976. [Twayne's United States Authors Series 260]

- Harry Hayden Clark: The Literary Influences Of Philip Freneau. In: Studies in Philology 22, 1925.

- Harry Hayden Clark: What Made Freneau the Father of American Poetry. In: Studies in Philology 26, 1929.

- Samuel E. Forman: The Political Activities of Philip Freneau. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1902. archive.org

- Lewis Leary : That Rascal Freneau: A Study in Literary Failure. Rutgers University Press, Brunswick, NJ 1941.

- Lewis Leary: Philip Freneau. In: Everett Emerson (Ed.): Major Writers of Early American Literature. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison 1972.

- Philip Merrill Marsh: Jefferson and Freneau. In: American Scholar 16, 1947.

- Philip Merrill Marsh: The Works of Philip Freneau: A Critical Study. Scarecrow Press, Metuchen, NJ 1968.

- Paul Elmer More : Philip Freneau. In: Nation 85, October 10, 1903.

- Richard C. Vitzthum: Land and Sea: The Lyric Poetry of Philip Freneau. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 1978.

- Eric Wertheimer: Commencement Ceremonies: History and Identity in 'The Rising Glory of America,' 1771 and 1786. In: Early American Literature 29: 4, 1994, pp. 35-58.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Leary: That Rascal Freneau , p. 5.

- ^ Leary: That Rascal Freneau , p. 13.

- ^ Leary: That Rascal Freneau , p. 16.

- ↑ See, for example, the article in Princeton Alumni Weekly: The fabulous Class of '71 (1771, that is) , January 23, 2008

- ^ Leary: That Rascal Freneau , p. 20.

- ^ Reprinted in Austin, pp. 80-81.

- ↑ Bowden, pp. 29-30

- ↑ A detailed description of the incident can be found in Freneau's Some account of the capture of the ship “Aurora”. Published by MF Mansfield & A. Wessels, New York 1899. archive.org

- ↑ Vitzthum, p. 45ff.

- ↑ Harry Ammon: The Genet Mission. WW Norton, New York 1973, p. 78.

- ↑ to oppose the measures of government and, by false insinuations, to disturb the public peace ... In common life, it is thought ungrateful for a man to bite the hand that puts bread into his mouth; but if the man is hired to do it, the case is altered. Quoted in: John Chester Miller: Alexander Hamilton and the Growth of the New Nation. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick and London, 2003, p. 345.

- ↑ Miller, p. 347.

- ↑ Jefferson deals with the "press war" over Freneau and Fenno in a long letter to Washington, dated September 9, 1792: loc.gov of the Thomas Jefferson Papers of the Library of Congress

- ↑ His paper has saved our constitution, which was galloping fast into monarchy, & has been checked by no one means so powerfully as by that paper. It is well and universally known, that it has been that paper which has checked the career of the monocrats, & the President, not sensitive of the designs of the party, has not with his usual good sense and sang froid, looked on the efforts and effects of this free press and seen that, though some bad things have passed through it to the public, yet the good have preponderated immensely. In: The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. HW Darbey, New York 1859. Vol. IX, p. 145. Google Book Search

- ^ Washington Irving: Life of George Washington. Volume VGP Putnam, New York 1859, p. 164: It appears to us rather an ungrateful determination on the part of Jefferson, to keep this barking cur in his employ, when he found him so annoying to the chief, whom he professed, and we believe with sincerity, to revere.

- ^ Moses Coit Tyler : The Literary History of the American Revolution, 1763-1783. GP Putnam, New York 1897. He was the poet of hatred, rather than of love. He had a passion for controversy. His strength lay in attack; his characteristic measure was the iambic. Among all his verses, the reader finds scarcely one lyric of patriotic enthusiasm, nor many lines to thrill the hearts of the Revolutionists by any touch of loving devotion to their cause, but everywhere lines hot and rank with sarcasm and invective against the enemy. He did, indeed, give ample proof that he had the genius for other and higher forms of poetry; yet it was as a satirist that he won his chief distinction, as a satirist, likewise, doing always the crudest work of that savage vocation with the greatest relish.

- ^ Vernon Louis Parrington, Main Currents in American Thought. Vol. 1. (1927) chap. III: virginia.edu : In his republicanism Freneau had gone far in advance of the Federalists. He was a democrat while they remained aristocrats. He had rid himself of a host of outworn prejudices, the heritage of an obsolete past, which held them in bondage. He had read more clearly the meaning of the great movement of decentralization that was shaping a new psychology, and must lead eventually to democratic individualism. He had no wish to stay or that development; he accepted it wholly with all its implications. He had freed his mind from the thralldom of caste; he was impelled by no egoistic desire to impose his will upon others; [...] In championing the cause of democracy, he championed a score of lesser causes: Unitarianism, deism, antislavery, Americanism in education: thereby bringing down on his head the resentment of all the conservatisms, religious, political, economic, social, then prospering in America. Nevertheless he went his way through a sordid world of politicians and speculators, feeding upon whatever shreds of beauty he met with, a dreamer and an idealist sneered at by exploiters, a spirit touched to finer issues than his generation cared for.

- ^ Henry Adams: History of the United States of America During the First Administration of Thomas Jefferson. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1889, p. 125: If in the last century America could boast of a poet who shared some of the delicacy if not the grandeur of genius, it was Philip Freneau; whose verses, poured out for the occasion, ran freely, good and bad, but the bad, as was natural, much more freely than the good.

- ↑ On the debate about the first American novel, see: Cathy Davidson: Revolution and the Word: The Rise of the Novel in America. Oxford University Press, New York 1986, pp. 84ff.

- ↑ Bowden, pp. 31-33

- ↑ James L. Machor: Pastoral Cities: Urban Ideals and the Symbolic Landscape of America. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison 1987, pp. 82-83.

- ↑ Leary 1972, p. 250.

- ↑ Leary 1972, p. 267

- ^ Richard C. Vitzthum: Philip Morin Freneau. In: Emory Elliott (Ed.): Dictionary of Literary Biography. Volume 37: American Writers of the Early Republic. Gale, Detroit 1985, pp. 170ff.

- ^ Bowden, p. 53; Vitzthum 1985, p. 170

- ↑ Vitzthum 1985, p. 176: The flower exists in a nonhuman, unfeeling, unknowing realm where things come and go, exist or cease to exist, meaninglessly. It is the gap between the speaker's concern for the flower and the flower's indifference to the speaker that the poem stresses everywhere.

- ^ Freneau failed at almost everything he attempted

- ↑ Leary 1972, p. 270

- ↑ A Fragment of Bion, 1822

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Freneau, Philip |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Freneau, Philip Morin (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 2, 1752 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New York City |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 18, 1832 |

| Place of death | Middletown Point |