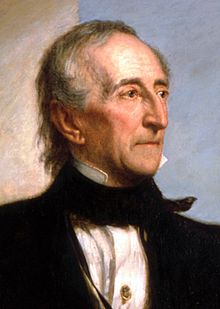

John Tyler

John Tyler (born March 29, 1790 in Charles City County , Virginia , † January 18, 1862 in Richmond , Virginia) was an American politician and served as the tenth President of the United States from April 4, 1841 to March 4, 1845 in Office. He was the first unelected incumbent in the White House . After the death of William Henry Harrison , he rose from the office of tenth vice president to president. He was previously governor of Virginia and represented that state in the US Senate .

Life to the presidency

Tyler came from a rich family of planters and was born the sixth of eight children and the second oldest son in June 1790. His father, John Tyler Sr., was a childhood friend of Thomas Jefferson and, unlike his father, who served in the British Crown , a supporter of the American Revolution . Tyler Sr. was a member of the Virginia House of Representatives until 1786 . He then held the post of judge at the state's highest criminal court until 1798. Tyler's mother, Mary Armistead, was the daughter of a wealthy Virginia planter. From 1802 to 1807 he attended the College of William & Mary and then learned law from his father and a cousin. Then he worked as a lawyer. In 1813 he married Letitia Christian (1790–1842).

From 1811 to 1816 and again from 1821 to 1825 he was a member of the Virginia House of Representatives , from 1817 to 1821 he represented the state of Virginia in the House of Representatives of the United States . He was Governor of Virginia from 1825 to 1827 . During this time he campaigned, albeit unsuccessfully, for the improvement of the public school system and infrastructure , before he was elected to the US Senate in 1827 as the successor to John Randolph of Roanoke . From March 1835 to December 1835 he was President pro tempore of the United States Senate . Vice-President Martin Van Buren was the official President of the Senate at the time .

Politically, Tyler was a supporter of the ideas of Thomas Jefferson and belonged to the Democratic Republican Party at the beginning of his career . Even his father, John Tyler Sr. was friends with Jefferson and at the same time his roommate at the College of William & Mary . After the Democratic Republican Party broke up, Tyler joined the Democratic Party and supported Andrew Jackson . During the nullification crisis of 1832 and 1833, Tyler first tried to take a mediating position. Jackson was the only Senator to openly reject the military enforcement of the tariff against South Carolina in 1833. Because of this, Tyler, who was also a staunch advocate of "States rights," left the Democratic Party and joined Henry Clay and his newly formed Whig Party .

In 1838, Tyler, who was himself a slave owner, was elected President of the Virginia African Colonization Society . Such colonization societies in the USA set themselves the goal of deporting some of the released slaves living in the states to Africa . Its members consisted of both opponents of slavery and slave owners who could not imagine that white and black people could live together and therefore promoted the deportation of the freed slaves.

William Henry Harrison selected him in the run-up to the 1840 presidential election as its vice-president . After winning the election, he took up this position on March 4, 1841. At 31 days it should be the shortest vice-presidency in American history to date. During this short period, however, Tyler had de facto exerted no influence on the government policy of President Harrison and withdrew to his country residence.

Presidency (1841-1845)

Assumption of office

In the early hours of April 5, 1841, at his family home in Williamsburg, Tyler received news of President Harrison's death from pneumonia. This was the first time in the history of the United States that an incumbent president died and the duties of the head of state for the remaining term of office, in Tyler's case three years and eleven months, were transferred to the previous vice president. Despite the fact that the American Constitution stipulated this succession plan, the exact wording of this rule made it controversial as to whether Tyler was a full president or only had presidential powers and duties. Some politicians, such as the House of Representatives and former President John Quincy Adams believed that Tyler was still Vice President and was only responsible for running the business of President. Tyler turned out, however, vehemently on the view that he was no Executive President (Acting President) , but with the death of Harrison that the Office is fully transferred to him. He had letters sent back unopened from politicians who only regarded him as the executive president and were addressed to the acting president . The US Congress also used the title "President" in its legislative texts. On April 6, 1841, Tyler officially took the President's oath of office.

Tyler's stance that the vice-president would actually take over the presidency in full in the event of the president's ultimate resignation created a historical precedent for interpreting the succession plan that would apply to all future vice-presidents until 1967. This practice was codified into law in 1967 with the 25th Amendment to the Constitution , after a president had fallen out of office seven more times . Only then was it possible to appoint a new Vice President at a later date. Tyler was unable to appoint a new vice president after he took office, leaving the office vacant until 1845.

Domestic politics

On April 9, 1841, Tyler delivered his factual inaugural address . In it he affirmed his principles of the political philosophy of Thomas Jefferson , affirmed the limitation of the power of the federal government and advocated strict observance and interpretation of the US Constitution.

After he took office, Secretary of State Daniel Webster informed him that cabinet decisions had so far been made by consensus, which Tyler rejected. In this context, the following quote is ascribed to him:

“I beg your pardon, gentlemen; I am very glad to have in my Cabinet such able statesmen as you have proved yourselves to be. And I shall be pleased to avail myself of your counsel and advice. But I can never consent to being dictated to as to what I shall or shall not do. I, as President, shall be responsible for my administration. I hope to have your hearty co-operation in carrying out its measures. So long as you see fit to do this, I shall be glad to have you with me. When you think otherwise, your resignations will be accepted. "

“I apologize, gentlemen. I am glad to have such capable statesmen as you in my cabinet. I am pleased to take your advice. But I can never accept a practice like this in which I am dictated what to do and what not to do. As President, I am responsible for my administration. If you agree, I am glad to keep you in my government. If you think differently, I will be happy to accept your resignation requests. "

As a southern aristocrat, the former Virginia state governor and senator was only created to attract southern voters to Harrison (the slogan was: Tippecanoe and Tyler, too ). His political views, however, were opposed to the Whig Party , which represented the interests of the Northeast States with their emerging industry and business world - so he vetoed the establishment of a national bank, which was a fundamental concern of the Whigs and, in a classic democratic position, a presidential veto its most prominent Senator was Henry Clay .

After Tyler again vetoed the new bill, which was barely amended to expose him, on September 11, 1841, by order of Henry Clay, almost all of the ministers appointed by William Henry Harrison resigned one after the other. Clay had run the Harrison government from the background, as previously agreed, and then wanted to become the next president, but now saw this goal as jeopardized if Tyler, who ignored his instructions, managed a successful presidency. With this step, Clay wanted to force him to resign, which would have promoted his loyal President pro tempore of the Senate, Samuel L. Southard, to president. When Secretary of State Daniel Webster remained the only one in office because he wanted to bring the Webster-Ashburton Treaty to the conclusion of the Canadian border and saw himself as independent, Tyler drew new hope in the fight against Clay.

When Tyler refused to resign or give in, he was expelled from the party two days later on September 13. The reaction was that he went along with the Democrats more and more and in 1844 even appointed the prominent Southern Democrat John C. Calhoun as Secretary of State in his cabinet . The two-party system was inextricably linked to the North-South conflict until the Civil War : Now the Whigs were irrevocably the Northern States - and the Democrats the Southern Party. Tyler himself has remained non-party until the end of his life .

After further vetoes by Tylers against the Whigs bills, such as the establishment of a national bank and various customs laws, the impeachment of the president was even discussed in 1842 . Up until then, the US presidents had used their veto power very sparingly and only failed to sign laws because of constitutional concerns. Tyler's objections, however, were politically motivated from the perspective of the senators and MPs. A corresponding committee in the House of Representatives chaired by the MP and former President John Quincy Adams ultimately did not come to the conclusion that the Congress should initiate proceedings for impeachment, especially since the congressional elections in the fall of 1842 were unfavorable for the Whigs and theirs Had lost majority in the House of Representatives. Impeachment would have been difficult because a US president can only be removed for legal misconduct. The constitution does not provide for voting out for political reasons before the end of the term of office, for example by means of a vote of no confidence .

In 1841 the Preemption Act was passed, favoring settlers over land speculators , encouraging immigration from Iowa , Illinois , Wisconsin, and Minnesota .

At that time, conflicts between native Protestants and immigrant Catholics (especially from Ireland ) escalated . An anti-Catholic party was even formed, known as the Know-Nothing Party . Tyler, on the other hand, was tolerant of religious matters. In a letter dated July 10, 1843, he extolled the "complete separation of church and state " in the United States as a "great and noble experiment."

Foreign policy

Since Tyler was only able to act to a very limited extent in domestic affairs due to the majority in Congress, he increasingly focused on foreign affairs, where successes could indeed be achieved. In 1842 the Second Seminole War ended and its then Secretary of State Daniel Webster was able to achieve a border treaty with the United Kingdom , which established the border between Maine and Canada . The Webster-Ashburton Treaty also ended the Aroostook War . Cooperation to stop the slave trade was also agreed. Tyler also warned foreign powers against bringing Hawaii under their control. In 1844, with the Treaty of Wanghia, the ports of China were opened to American trade.

Annexation of Texas and election of 1844

On February 28, Polk and other politicians as well as high dignitaries were guests on a river cruise of the recently commissioned USS Princeton , a novel warship of the United States Navy , along the Potomac River . When a shot was fired in the passage of the Mount Vernon manor to demonstrate the firepower of the modern ship artillery , a devastating explosion occurred on the upper deck, killing several people and destroying the ship. Among the dead were Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur , Secretary of the Navy Thomas Walker Gilmer , Tyler's valet, and David Gardiner, the father of Tyler's future wife, Julia Gardiner Tyler .

During the election campaign of 1844 , Tyler was nominated for president by a splinter group of the Democratic Party in Baltimore . However, since it was not nominated by any of the major parties, he had no chance from the start, and even former President and founder of the Democrats Andrew Jackson wrote a letter to him to appeal to him to withdraw his candidacy in order to defeat the Democratic candidate, James K. Polk , no harm, and at the same time publicly advocated taking Tyler back to the Democrats. Polk's historically enormously significant nomination as a consensus candidate instead of the widely anticipated nomination of expansion opponent Martin Van Buren was also a result of Tyler's support for expansion. In order not to endanger Polk's victory over Tyler's intimate enemy Henry Clay and because of his own lack of chances, Tyler withdrew his candidacy in August of that year. Polk won the fall election and became the eleventh President of the United States on March 4, 1845 .

After Congress had previously rejected the incorporation of Texas, Tyler interpreted Polk's election victory as a vote by the American people for admission to the Union. After another vote, the Congress approved this project. On March 1, 1845, Tyler signed the resolution annexing Texas . On March 3, 1845, his last full day in office, Tyler confirmed admission from Florida to the United States . Also on March 3, Congress dealt with a veto by Tylers against a relatively insignificant bill, which was overruled with the required two-thirds majority in both chambers. It was the first time in United States history that a presidential veto had been rejected.

Marriages and offspring

Tyler had fifteen children, more than any other US president. His marriage to his first wife Letitia (1790–1842) in 1813 resulted in eight children: Mary (1815–1847), Robert (1816–1877), John (1819–1896), Letitia (1821–1907), Elizabeth ( 1823-1850), Anne (1825-1825), Alice (1827-1854) and Tazewell (1830-1874). Letitia died in 1842 at the age of 51 after a stroke .

In 1844 Tyler married Julia Gardiner (1820–1889), 30 years his junior , with whom he had seven more children: David (1846–1927), John Alexander (1848–1883), Julia (1849–1871), Lachlan (1851–1902 ), Lyon (1853–1935), Robert Fitzwalter (1856–1927) and Pearl (1860–1947).

Son David, born in 1846, represented Virginia in the US House of Representatives between 1893 and 1897. The son Lyon Gardiner Tyler, born in 1853, fathered three sons with his second wife, who was 35 years his junior, two of whom were still alive in June 2019: Lyon Gardiner Tyler, Jr. (* 1924) and Harrison Ruffin Tyler (* 1928). This makes John Tyler by far the oldest US President with grandchildren still alive.

Later years

After the inauguration of his successor James K. Polk on 4 March 1845, Tyler and his family moved to his 1,600 acre large plantation Sherwood Forest, which was managed by dozens of slaves back.

After the end of his tenure as president, he did not appear politically until 1861. It was not until February 1861, a few weeks before the start of the American Civil War , that Tyler, on Virginia's initiative, led a peace conference in Washington, DC , at which delegates from 22 states tried in vain to find a compromise between the free and slave-holding states.

In the run-up to the civil war, he campaigned for secession, was also elected to the Confederation Congress , but died before he could take this office. On January 18, 1862, in Richmond, shortly before the age of 72, he suffered a fatal stroke.

Tyler was buried in Richmond's Hollywood Cemetery. In 1911, the US Congress made money available for a monument on his grave. Tyler's estate and papers were largely lost during the Civil War, as his Sherwood Forest plantation was looted by Union forces.

Posthumous effect

Since Tyler embodies the precedent that the Vice President moves up to the presidency, he has a defining meaning for the constitutional history of the USA. Some historians have described his tenure as the most disappointing in American history to date, and some saw it as a portent of the impending civil war. The later President Theodore Roosevelt even called him "a politician of monumental littleness" (in German roughly: a politician of monumental insignificance).

literature

- Horst Dippel : John Tyler (1841-1845): President without a party. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 6th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-58742-9 , pp. 139–144.

- Edward P. Crapol: John Tyler: The Accidental President . (Paperback edition). University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 2012, ISBN 978-0-8078-7223-9 .

- Gary May: John Tyler. Times Books, New York City 2008, ISBN 978-0-8050-8238-8 .

- Oliver Perry Chitwood: John Tyler: Champion of the old South. D. Appleton-Century Company, New York 1939, LCCN 39-022996 .

Web links

- John Tyler in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (English)

- John Tyler in the nndb (English)

- John Tyler Jr. in the National Governors Association (English)

- Official White House biography ( January 15, 2009 memento on the Internet Archive ) (archived)

- American President: John Tyler (1790-1862). Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia (English, editor: William Freehling)

- The American Presidency Project: John Tyler. University of California, Santa Barbara database ofspeeches and other documents from all American presidents

- John Tyler, Vice President of the United States , at the Historian's Office of the Senate (PDF) (English; 64 kB)

- Life Portrait of John Tyler on C-SPAN , May 17, 1999, 150 minutes (English-language documentation and discussion with historian Edward P. Crapol and guided tour of the Sherwood Forest Plantation )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gary May: John Tyler. 2008, p. 10f.

- ^ A b William Freehling: John Tyler: Life before the Presidency . Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia , accessed on 17 April 2018th

- ↑ Horst Dippel: John Tyler (1841-1845). President without a party. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 139–144, here: pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Gary May: John Tyler. 2008, p. 1f.

- ↑ Horst Dippel: John Tyler (1841-1845). President without a party. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 139–144, here: pp. 141–142.

- ^ William Freehling: John Tyler: Life in Brief . Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia , accessed on 17 April 2018th

- ↑ Oliver Perry Chitwood: John Tyler. Champion of the Old South. New edition 1964, Russell & Russell, p. 149.

- ^ A b William Freehling: John Tyler: Domestic Affairs . Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia , accessed on 17 April 2018th

- ↑ Oliver Perry Chitwood: John Tyler. Champion of the Old South. New edition 1964, Russell & Russell, p. 303.

- ↑ Edward P. Crapol: John Tyler, the Accidental President . Revised new edition (paperback), University of North Carolina Press, 2012, Foreword, p. Xviii (Google Books).

- ^ William Freehling: John Tyler: Foreign Affairs . Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia , accessed on 17 April 2018th

- ↑ Horst Dippel: John Tyler (1841-1845). President without a party. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 139–144, here: pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Gary May: John Tyler. 2008, pp. 106-108.

- ^ William Freehling: John Tyler: Campaigns and Elections . Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia , accessed on 17 April 2018th

- ↑ Horst Dippel: John Tyler (1841-1845). President without a party. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 139–144, here: pp. 143–144.

- ↑ Edward P. Crapol: John Tyler, the Accidental President . Revised new edition (paperback), University of North Carolina Press, 2012, p. 4 (Google Books).

- ↑ Oliver Perry Chitwood: John Tyler. Champion of the Old South. New edition 1964, Russell & Russell, p. 478.

- ↑ Oliver Perry Chitwood: John Tyler. Champion of the Old South. New edition 1964, Russell & Russell, p. 479.

- ↑ Chloé Belleret: Leur grand-père est né au 18e siècle: l'incroyable histoire des Frères Tyler. In leparisien.fr, June 7, 2019, accessed on May 28, 2020.

- ↑ How two of President John Tyler's grandsons are still alive, 174 years later cbsnews.com, March 6, 2018.

- ^ William Freehling: John Tyler: Life after the Presidency . Miller Center of Public Affairs of the University of Virginia , accessed on 17 April 2018th

- ↑ John Tyler in the Find a Grave database .

- ↑ Horst Dippel: John Tyler (1841-1845). President without a party. In: Christof Mauch (Ed.): The American Presidents. 5th, continued and updated edition. Munich 2009, pp. 139–144, here: pp. 139–144.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tyler, John |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American politician, 10th President of the USA (1841–1845) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 29, 1790 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Charles City County , Virginia |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 18, 1862 |

| Place of death | Richmond , Virginia |