House Divided Speech

The house-divided speech is a speech given by Abraham Lincoln on June 16, 1858 at the Old State Capitol in Springfield, Illinois . It was the start of the Republican Party's election campaign in the US state of Illinois for the United States Senate elections , which took place on November 2, 1858. Lincoln warned in his speech against the division of the nation and the spread of slavery in the territories and states where it was illegal, such as Illinois. Lincoln was defeated by his rival in the elections, but the speech made him known throughout the USA and enabled him to run for president two years later. It is counted among the greatest speeches in American history.

prehistory

Slave question

In the years prior to the outbreak of the Civil War , the slave issue was the main domestic political issue in the United States . Although it had in 1820 in Missouri Compromise that the relatively far-reaching to the North agreed to Missouri as a slave state admitted to the Union, but all areas of the Louisiana Territory to the north 36 ° 30 'north latitude were to be slaves free should. This compromise was repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act , a law passed by the United States Congress in May 1854 on the initiative of Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas . After that, it should be left to the sovereignty of the people of the individual states and territories whether they wanted to allow slavery or not. The law was actually only intended to get the southern states to approve a railroad line from Illinois to California , but in the following years it led to civil war-like unrest in the Kansas Territory , which was north of the compromise line, which went down in history as Bleeding Kansas .

In 1857, the Kansas Constituent Assembly presented the Lecompton Constitution , named after the place where it was formed, a draft constitution that allowed slavery. Since the subsequent plebiscite could only vote on whether or not more slaves could be imported into Kansas, it was boycotted by Free Soilers and other opponents of slavery . The Kansas Constitution was therefore approved and adopted by Democratic President James Buchanan . His party friend Douglas, who claimed that he did not care what the result of the votes he had advocated on slavery, saw the principle of popular sovereignty being violated by the procedure chosen and organized a majority in Congress against the Lecompton Constitution , in which except Democrats also met MPs from the Whigs and the Republicans, who had just been formed four years earlier. As a result, rumors grew that Douglas could break up with the Democrats and possibly even join the Republicans.

That same year, the Supreme Court ruling in the Dred Scott v. Sandford caused a stir. Dred Scott was an African American slave who sued for release after his owner took him to Illinois and Wisconsin, where slavery did not exist. The Supreme Court under its chairman Roger B. Taney dismissed the case on March 6 in 1857 with seven votes to two, as in the United States Constitution enshrined fundamental rights to call including the right to the courts, for African-Americans do not apply. At the same time, Taney declared that Congress was not at all competent to decide on slavery in the territories: the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional.

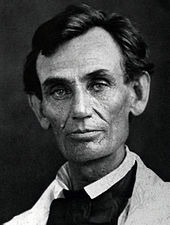

Lincoln's career

Abraham Lincoln, a lawyer and politician from Springfield, Illinois, was a moderate opponent of slavery. Although he was strictly against its expansion into new states and territories, he did not adopt the arguments of the abolitionists who wanted to abolish them immediately. He therefore spoke out in favor of maintaining the Fugitive Slave Act passed in 1850 , which obliged non-slavery states to extradite escaped slaves. In 1854, Lincoln, elected to the Whigs , resigned from his seat in the United States House of Representatives , to which he had been elected in 1846, and ran for the Senate, but was not elected. In 1856 he joined the Republican Party. On June 16, 1858 he was unanimously elected as a candidate for the upcoming Senate election by the approximately 1,000 delegates of the Illinois Republican State Convention. The previous mandate holder and thus Lincoln's rival candidate was Stephen Douglas. On the evening of the same day, Lincoln gave a speech of about half an hour to the delegates, which would go down in history as a house-divided speech. Unlike his other speeches, which he improvised on the basis of a few notes, Lincoln had carefully formulated this speech in the weeks before and given it to his law firm partner William Herndon, who found it too radical. Lincoln didn't want to change anything, so he memorized them so he could speak without a manuscript.

content

Lincoln began his speech with a familiar phrase used by Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts in the 1830 nullification crisis : knowing where you stand and where you are going will help you judge what to do and how. Although efforts have been made to end agitation for slavery since 1854 (the year of the Kansas-Nebraska Act), it continues to increase. This will only end in a crisis , in the ancient sense of the word in a decision-making situation. With that he came to the much-quoted formulation that should give the speech the title:

“Any house that is divided in itself will not stand. I believe that this government cannot survive in the long run by being half for slavery and half for freedom. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved; I don't expect the house to collapse, but I do expect it will stop being divided. It will either be completely one or completely the other. "

The metaphor of the divided house referred to the New Testament : According to Mk 3,25 Luth and Mt 12,25 Luth , Jesus of Nazareth defended himself after an exorcism against the suspicion that he himself was in league with the devil : “How can he? Satan cast out Satan? If an empire is divided, it cannot endure ”. Lincoln had used the metaphor several times in his speeches, the first time in 1843 when it came to unity within the Whig party.

As the speech went on, Lincoln predicted that either the opponents of the spread of slavery would prevail, reassuring the public with the thought that it would eventually be abolished in the course of time, or its proponents. So he did not speak out in favor of abolishing slavery, only in favor of curbing its further expansion. Nonetheless, he saw a trend towards expansion, since with the Dred Scott decision, the Kansas-Nebraska Act and Buchanan's inauguration, a legal “machine” had been set up, according to which no one should in future be allowed to object if someone decides to enslave someone else. Although he had no proof of this, he found reasons for plausibility in another linguistic image: He imagined a half-timbered building whose components had been brought in at different times by, for example, "Stephen, Franklin, Roger and James", and were perfectly matched and coordinated:

"In this case it is impossible for us not to assume that Stephen, Franklin, Roger and James understood each other from the start and that they all had a common plan or blueprint before work began."

By the four first names, Lincoln meant the four participants in the conspiracy he wanted to convince his audience of: his opponent Stephen Douglas, former President Franklin Pierce , Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney and President James Buchanan, all members of the Democratic Party. So they had come together to use the measures mentioned, the timing of which, as Lincoln explained in detail, was precisely coordinated, to prepare and enforce the legal opinion according to which the US Constitution does not allow any state to prohibit slavery within its borders:

“Whether we like it or not, such a decision is likely to come and soon befall us unless the power of the current political dynasty is confronted and overthrown. We lie down and beautifully dream that the people of Missouri are on the verge of freeing their state, and we wake up to reality and the Supreme Court has instead made Illinois a slave state. "

This "dynasty", by which Lincoln meant the Democratic Party, for which Stephen Douglas sat in the Senate as representative of Illinois, should be overthrown. Even after his quarrel with the President, which Lincoln dismissed as a “little quarrel”, Douglas was not the right man as an ally: Although he surpassed all Republicans in importance and influence, but - and here Lincoln quoted the Bible again - “a living dog is better than a dead lion ”( Koh 9.4 Luth ). Douglas is, if not dead, toothless and imprisoned, and based on his previous arguments, he could not stand up against the spread of slavery. In this context, Lincoln even accused him of wanting to reintroduce the transatlantic slave trade , which was prohibited by a federal law of 1808. The only means to achieve the goal is the Republican Party, which is composed of disparate parts, but now has to show unity. You have to be steadfast and determined: "Sooner or later, that's for sure, victory will come."

interpretation

This speech has been interpreted differently. The non-fiction author Ronald D. Gerste, for example, sees it as a correct description of the state of the USA on the eve of the civil war, which Lincoln wanted to avoid. The American communications scientist David Zarefsky contradicts this: Lincoln was not concerned with a prophecy of an impending civil war, but in the concrete political situation of early summer 1858 with the unity of the Republican Party, to which the metaphor of the "house that is divided, “Must be applied as well as to that of the United States as a whole.

From various quarters, the allegations that Lincoln made in his speech are referred to as the conspiracy theory. David Zarefsky names several features of conspiracy arguments that apply to the speech: it offered a coherent explanation for events that otherwise seemed pointless or incomprehensible, it polarized between good and evil and thus offered orientation in confusing times, and it could not be refuted , for, had Douglas denied being part of the conspiracy, it would only have made Lincoln's claims even more plausible. The Americanist Michael Butter sees three assumptions as typical features of a conspiracy theory: There are no coincidences, everything is connected, and nothing is what it seems. Therefore, conspiracy theorists tended to argue "in the mode of inference " and to infer the supposed intentions and plans from the result of a chain of events. Lincoln's house-divided speech is a "prime example" of this approach. Indeed, it was somewhat of a far-fetched assumption that Buchanan had something to do with the Kansas-Nebraska Act which he had not been able to participate in drafting as envoy to Britain , and even if he had, his party would not have nominated him as a presidential candidate. The rift between Douglas and Buchanan over the question of the Lecompton Constitution also makes Lincoln's claim that the two are in cahoots seem unreliable. But the prospect that the Supreme Court would declare slavery legal across the Union was, according to British historian Richard Carwardine, quite realistic.

The belief in a "slave power conspiracy," which would use a variety of means to impose slavery on the free states, was widespread among Republicans and other opponents of slavery such as Lincoln's audiences, and seemed normal to them and to be completely rational assumption. The fight against this alleged conspiracy, which seemed to jeopardize their civil rights , and indeed their chances of finding work for whites at all, and not so much the fight against slavery itself, was at the center of the republican agitation. The notion that the conspirators had already taken over the entire government, from the president to the president of the Supreme Court to a prominent senator, distinguishes Lincoln's conspiracy theory from that of the 18th and 19th centuries, in which the conspirators mostly acted as foreign agents be imagined. Lincoln also believed in such a conspiracy. According to historian Erich Angermann , he responded with the house-divided speech to the book Cannibals All! by George Fitzhugh, who considered slavery practiced in the southern states to be more humane than wage slavery in the northern states and who advocated a mild form of slavery for white workers. In more than fifty speeches that he gave from 1854 to 1860, he mentioned the slave power conspiracy; looking back on the House Divided speech, he noted: “In it I have arranged a chain of indisputable facts which I believe to prove the existence of a conspiracy to spread slavery across the nation ”. In the specific situation of June 16, 1858, Lincoln used this conspiracy theory to make his audience understand the urgency of the situation and dissuade them from seeing Douglas as an eligible candidate after his break with the president.

consequences

Lincoln was very pleased with the house-divided speech and had it published in the Illinois State Journal . His advisors had advised him in vain, who correctly foresaw that Douglas would use them against him in the election campaign to portray Lincoln as a radical abolitionist. This estranged him from moderate former Whig members in central Illinois. In fact, it was viewed as a declaration of war, along with a recently given speech by the future Secretary of State William H. Seward - Seward had called the slave question an "irrepressible conflict." Douglas used the speech in the campaign to lump Lincoln together with radical abolitionists like Owen Lovejoy . Douglas also used it as evidence for allegations that Lincoln contradicted the founding fathers of the United States , who allowed slavery in some states and banned slavery in others: a house could therefore exist without uniformity on this issue. In addition, Douglas assumed that it was less the United States than the Republican Party that was at odds with itself. Lincoln traveled after Douglas to correct these claims until the two candidates agreed to hold seven public debates that went down in history as the Lincoln-Douglas Debates . The speech battles between the 1.95 m tall Lincoln and Douglas, whose height of 1.63 m had earned him the nickname "little giant", attracted a wide audience. Douglas kept referring to the house-divided speech. In order to defend himself against the accusation of abolitionism, Lincoln finally resorted to openly racist remarks about the supposed superiority of the white race: African Americans should continue to be banned from voting, not voting on juries and not marrying whites.

It didn't help: Lincoln lost the election. He had got more votes, but because of Illinois suffrage, senators were not elected directly by the people, but by the state parliament, and Douglas' supporters had a majority there. On January 5, 1859, Douglas was confirmed as Senator from Illinois by 54 votes to 46. Nonetheless, the house-divided speech, which, in the opinion of numerous observers, caused Lincoln's defeat, is considered to be one of his greatest successes: With its radicalism, it earned the Springfield lawyer national prominence and popularity among all opponents of slavery. This was a prerequisite for his being elected President of the United States two years later.

literature

- Don E. Fehrenbacher: The Origins and Purpose of Lincoln's 'House-Divided' Speech . in: Mississippi Valley Historical Review . 46, No. 4 (1960), pp. 615–643 (Reprinted in: Sean Wilentz (Ed.): The Best American History Essays on Lincoln . Palgrave MacMillan, New York 2016, pp. 149–174).

- Michael Leff: Rhetorical Timing in Lincoln's 'House Divided' speech . The Van Zelst Lecture in Communication, Evanston: Northwestern University 1983.

- Michael William Pfau: The House That Abe Built: The “House Divided” Speech and Republican Party Politics . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 2, Heft 4 (1999), pp. 625-651.

- David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, Issue 3: Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds (2010), pp. 421–453

Web links

- House Divided Speech on abrahamlincolnonline.org

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jolyon P. Girard, Darryl Mace and Courtney Michelle Smith (Eds.): American History through its Greatest Speeches: A Documentary History of the United States . Vol. 2, ABC Clio, Santa Barbara / Denver / London 2017, pp. 152–157.

- ^ Howard Temperley, Regionalism, Slavery, Civil War, and the Reintegration of the South, 1815–1877 . In: Willi Paul Adams (ed.): The United States of America . (= Fischer Weltgeschichte , Vol. 30:) . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1977, pp. 96 and 100.

- ^ Richard Carwardine: Lincoln. A Life of Purpose and Power. Vintage Books, New York 2006, pp. 73 ff.

- ↑ David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, Issue 3: Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds (2010), p. 423 f.

- ^ Jörg Nagler : Abraham Lincoln. America's great president. A biography . CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 167.

- ^ Richard Carwardine: Lincoln. A Life of Purpose and Power. Vintage Books, New York 2006, pp. 66 f.

- ^ Richard Carwardine: Lincoln. A Life of Purpose and Power. Vintage Books, New York 2006, p. 361 f.

- ^ Richard Carwardine: Lincoln. A Life of Purpose and Power. Vintage Books, New York 2006, p. 52.

- ^ Don E. Fehrenbacher: The Origins and Purpose of Lincoln's 'House-Divided' Speech . In: Mississippi Valley Historical Review . 46, No. 4 (1960), p. 631; Jörg Nagler: Abraham Lincoln. America's great president. A biography . CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 173.

- ^ Jörg Nagler: Abraham Lincoln. America's great president. A biography . CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 173 f.

- ^ John Burt: Lincoln's Tragic Pragmatism . Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2013, ISBN 978-0-674-05018-1 , p. 124 (accessed from De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: "Rhetoric and Public Affairs" 13, Issue 3: "Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds" (2010), p. 430.

- ^ "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved - I do not expect the house to fall - but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other ". German translation quoted from Jörg Nagler: Abraham Lincoln. America's great president. A biography . CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 174.

- ↑ David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: "Rhetoric and Public Affairs" 13, Volume 3: "Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds" (2010), p. 427.

- ↑ David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: "Rhetoric and Public Affairs" 13, Issue 3: "Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds" (2010), p. 431.

- ↑ "In such a case, we find it impossible not to believe that Stephen and Franklin and Roger and James all understood one another from the beginning, and all worked upon a common plan or draft drawn up before the first lick was struck". German translation quoted from Michael Butter : "Nothing is what it seems". About conspiracy theories . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018, p. 70.

- ^ “Welcome, or unwelcome, such decision is probably coming, and will soon be upon us, unless the power of the present political dynasty shall be met and overthrown. We shall lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free; and we shall awake to the reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State. " Quoted from David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, Issue 3: Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds (2010), p. 435.

- ^ "Sooner or later the victory is sure to come." German translation quoted from Ronald D. Gerste : Abraham Lincoln. Founder of Modern America . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, p. 78.

- ↑ Ronald D. Gerste: Abraham Lincoln. Founder of Modern America. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, p. 78; similar to Wolfgang Mieder : "Many roads lead to globalization". For the translation and distribution of Anglo-American proverbs in Europe. In: Rolf Wilhelm Brednich (Hrsg.): Narrative culture. Contributions to cultural studies narrative research. Hans-Jörg Uther on his 65th birthday. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-021472-7 , p. 451 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, Issue 3: Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds (2010), pp. 422 and 428 ff .; similar to Don E. Fehrenbacher: The Origins and Purpose of Lincoln's 'House-Divided' Speech . in: Mississippi Valley Historical Review . 46, No. 4 (1960), pp. 627-631.

- ↑ For example by Don E. Fehrenbacher: The Origins and Purpose of Lincoln's 'House-Divided' Speech . in: Mississippi Valley Historical Review . 46, No. 4 (1960), p. 631; Eric J. Sundquist: Faulkner. The House Divided . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1983, p. 104; Jörg Nagler: Abraham Lincoln. America's great president. A biography . CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 175; David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, Issue 3: Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds (2010), p. 437; John Burt: Lincoln's Tragic Pragmatism . Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2013, ISBN 978-0-674-05018-1 , pp. 94 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, No. 3: Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds (2010), pp. 437-441.

- ↑ Michael Butter: "Nothing is what it seems". About conspiracy theories . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018, p. 69.

- ^ John Burt: Lincoln's Tragic Pragmatism . Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2013, ISBN 978-0-674-05018-1 , pp. 131 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Richard Carwardine: Lincoln. A Life of Purpose and Power. Vintage Books, New York 2006, p. 78.

- ↑ Michael Butter: Plots, Designs, and Schemes. American Conspiracy Theories from the Puritans to the Present. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2014, ISBN 978-3-11-034693-0 , pp. 170-190, etc. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Michael William Pfau: The House That Abe Built: The “House Divided” Speech and Republican Party Politics . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 2, Heft 4 (1999), p. 639.

- ↑ Michael Butter: Plots, Designs, and Schemes. American Conspiracy Theories from the Puritans to the Present. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2014, ISBN 978-3-11-034693-0 , pp. 189–198 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Jörg Nagler: Abraham Lincoln. America's great president. A biography . CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 173; David Herbert Donald : Lincoln. Simon and Schuster, New York 2011, p. 208.

- ↑ a b Erich Angermann: Abraham Lincoln and the renewal of the national identity of the United States of America (= writings of the Historical College. Lectures. Volume 7). Stiftung Historisches Kolleg, Munich 1984, p. 21 ( online , accessed on August 2, 2019).

- ↑ “In it, I have a string of incontestable facts which, I think arranged prove the existence of a conspiracy to nationalize slavery”. David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, Issue 3: Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds (2010), p. 434.

- ↑ David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, Issue 3: Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds (2010), p. 434.

- ^ Don E. Fehrenbacher: The Origins and Purpose of Lincoln's 'House-Divided' Speech . in: Mississippi Valley Historical Review . 46, No. 4 (1960), p. 619.

- ^ Richard Carwardine: Lincoln. A Life of Purpose and Power. Vintage Books, New York 2006, pp. 75-85; David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, Issue 3: Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds (2010), p. 445 f .; Jörg Nagler: Abraham Lincoln. America's great president. A biography . CH Beck, Munich 2009, pp. 176-189.

- ^ Jörg Nagler: Abraham Lincoln. America's great president. A biography . CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 190.

- ↑ David Zarefsky: Lincoln and the House Divided: Launching a National Political Career . In: Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, Issue 3: Special Issue on Lincoln's Rhetorical Worlds (2010), p. 446 ff.