Mountain Meadows Massacre

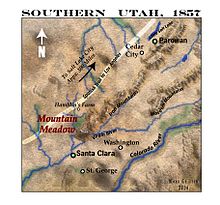

The Mountain Medows Massacre was a series of attacks on the emigrants of the Baker Fancher party ( Fancher party or Baker's Company , German: Baker Fancher Society ) in Mountain Meadows in Washington County in southern Utah in the United States , whole near what is now the small town of Enterprise. The attacks began on September 7 and culminated on September 11, 1857 in the mass slaughter of most members of the emigrant company by members of the Utah Territorial Militia , called the Nauvoo Legion from the district Iron County , Utah, along with some of the Southern Paiute - Indians .

The wagon train, made up of mostly Arkansas families , was traveling on a route to California that passed through the Utah Territory during what would become known as the Utah War . Upon arriving in Salt Lake City , the Baker Fancher Party headed south, eventually stopping at Mountain Meadows. While the emigrants camped in a meadow, leaders of the nearby militia, including Isaac C. Haight (1813–1886) and John D. Lee (1844–1877), made plans to attack the wagon train. The militia, officially known as the Nauvoo Legion, consisted of the Utah settlers, the Mormons . Wanting to create the impression of tribal hostility, they planned to arm some of the southern Paiute Indians and persuade the Native Americans to join forces with a larger group of militiamen disguised as Indians in an attack.

During the first attack by the militias on the covered wagon train, the emigrants initially defended themselves, which was followed by a five-day siege. Eventually, the leaders of the militias feared that some of the emigrants might see white men and that the real identity of their attackers would probably be revealed. The militia commander William H. Dame (1819-1884) then ordered his troops to kill the emigrants. At this point, the emigrants ran out of water and provisions, so they allowed some members of the militia - who were approaching under a white flag - to enter their camp. The militia officers assured the emigrants that they were protected and escorted them from their hastily built wagons . After moving a little further from the camp, the militia officers attacked the emigrants with the help of auxiliary troops hiding near the camp. The perpetrators killed all adults and older children (around 120 men, women and children in total). Seventeen children, all under the age of seven, were spared.

After the massacre, the perpetrators hastily buried the victims and ultimately left the corpses defenseless against wild animals and the climate. Local families took in the surviving children and much of the victims' possessions were auctioned off. After being interrupted by the American Civil War , the investigation resulted in charges being brought against nine people in 1874. However, of the men accused, only John Doyle Lee was tried. After two trials in the Utah Territory, Lee was sentenced to death by jury and executed on March 23, 1877 by the Utah firing squad.

Historians today attribute the massacre to a combination of factors, including "war hysteria" over a possible invasion of Mormon territory and "Mormon teachings" against outsiders who were part of the Mormon Reformation. Scholars debated whether senior Mormon leaders, including Brigham Young, had directly instigated the massacre or whether responsibility lay solely with local leaders in southern Utah.

history

Baker Fancher Party

In early 1857, several groups of expatriates from the northwestern Arkansas region began their migration to California and, along the way, formed a group known as the Baker Fancher Party. The groups came mainly from Marion County , Carroll County and Johnson County in Arkansas and had formed a wagon train at "Beller's Stand," south of Harrison , Arkansas, to emigrate to southern California. This group was initially referred to as both the Baker Train (German: Baker Train ) and the Perkins Train (German: Perkins Train ), but after other groups of emigrants from Arkansas had joined them to head west make it soon became known as the Baker Fancher Train (or Baker Fancher Party). The group was named after "Colonel" Alexander Fancher (1812-1857), who, after having made the trip to California twice, had become their main leader. By today's standards, the Baker Fancher Party was wealthy, carefully organized, and well equipped for the trip. Families and individuals from other states, including Missouri , joined them along the way. This group was relatively affluent and planned to replenish their supplies in Salt Lake City, as most of the wagon trains with settlers did at the time. The group reached Salt Lake City with about 120 members.

Interactions with Mormon settlers

At the time of the Fanchers' arrival, the Utah Territory was organized as a theocratic- led democracy, led by Brigham Young , who had established colonies along the California Trail and the Old Spanish Trail . President James Buchanan had recently given orders to send troops to Utah. Rumors spread in the area about the motives for a federal troop movement. Young then issued various orders urging the local population to prepare for the arrival of the troops. Eventually, Young declared martial law .

The Baker Fancher Party was denied access to supplies in Salt Lake City, so the group decided to take the Old Spanish Trail, which runs through southern Utah from there.

In August 1857, the Mormon Apostle George A. Smith (1817–1875) traveled from Parowan through southern Utah and instructed the settlers to hoard grain . On his way back to Salt Lake City on August 25th, Smith camped near the Baker Fancher Party on Corn Creek (near what is now Kanosh in Millard County ), 110 km north of Parowan. They had covered the 160 miles south of Salt Lake City and Jacob Hamblin suggested that the wagon train continue on the road and rest their cattle in Mountain Meadows, which had good grazing land and was adjacent to its homestead.

“When President Smith returned to Salt Lake City, Brother Thales Haskell and I went with him. On the way, we camped with a group of emigrants from Arkansas overnight on Corn Creek, twelve miles south of Fillmore, on what was then known as the southern route to California. They asked me about the street and wrote down the information I gave them. They expressed a desire to stay in a convenient location to recruit their teams before crossing the desert. I recommended them to do this at the southern end of Mountain Meadows, three miles from where my family lived. ... Brother Haskell and I stayed in Salt Lake City for a week and then went to our homes in southern Utah. On the way we heard that the Arkansas emigration company had been destroyed at Mountain Meadows. "

While most of the witnesses testified that the Fanchers were generally a peaceful society, whose members behaved well along the way, rumors of misdeeds spread.

“If you were to inquire about the people who lived here and in the country back then, you would find… that some of this Arkansas society… boasted of helping Hyrum and [his brother] Joseph Smith and the Mormons to have killed in Missouri and that they never wanted to leave the territory until similar scenes were re-enacted here. "

Brevet Major James Henry Carleton (1814–1873) directed the first federal investigation into the murders, published in 1859. He stuck to Jacob Hamblin's report that the Fancher party allegedly poisoned a spring near Corn Creek, allegedly resulting in the deaths of 18 cattle and two or three people who ate the contaminated meat. Carleton interviewed the father of a child who allegedly died from this poisoned spring and accepted the sincerity of the grieving father. But he also added the testimony of United States Deputy Marshall Rogers, who did not believe that the Fancher Party was capable of poisoning, given the size of the spring, since the water from the said spring would flow in such an amount and force that "A barrel of arsenic would not poison it". Carleton urged readers to ponder a possible explanation for the rumors of misdeeds, noting the general atmosphere of Mormon distrust of strangers at the time and that some locals seemed jealous of the Fancher Party's wealth.

Conspiracy and siege

The Baker Fancher Party left Corn Creek and continued the 201 km journey to Mountain Meadows, past Parowan and Cedar City , communities in southern Utah run by so-called Stake Presidents William H. Dame and Isaac C. Haight were. Haight and Dame were also the senior regional military leaders of the Nauvoo Legion (a Mormon militia). As the Baker-Fancher party approached, several meetings were held in Cedar City and in nearby Parowan the local leader of the movement of the Latter-day Saints : (English Latter Day Saint movement of) the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints ( The Church of Jesus Christ of L atter- d ay S aints shortly LDS place) was where thinking on the implementation of Youngs martial law declaration. On Sunday afternoon, September 6, after services, Haight held his weekly meeting of the Stake High Council (a high council in the Latter-day Saint Movement) and asked what should be done with the emigrants. The plan for a Native American massacre was discussed, but not all council members agreed that this was the right approach. The council decided not to do anything until the next day Haight dispatched a rider, James Haslam, to take an express message to Salt Lake City (a six-day tour on horseback) on the advice of Brigham Young, since Utah did not yet have a telegraph system. After the council, Isaac C. Haight decided to send a messenger south to John D. Lee. What Haight Lee said remains a mystery, but given the timing, it may have had something to do with the council's decision to await Brigham Young's advice.

The somewhat disheartened Baker Fancher Party found water and fresh pastureland for their cattle after reaching grassy, mountain-fringed meadows and the well-known stop on the Old Spanish Trail in early September 1857. They expected several days of rest and relaxation there before they got the next 40 miles out of Utah. However, on September 7th, the group was attacked by Mormon militiamen disguised as Indians and some southern Paiute Indians. The Baker Fancher Party defended itself by lowering their covered wagons together into a castle of wagons, chaining their wheels together, digging shallow trenches, and throwing earth both under and into their wagons, creating a strong barrier. Seven of the emigrants were killed during the opening attack and buried somewhere inside the wagon castle. Sixteen others of the Fancher group were wounded. The attack lasted five days, during which the besieged families had little or no access to fresh water or food for their animals and the stocks of ammunition to defend themselves were already exhausted. Meanwhile, the organization under local Mormon leadership reportedly collapsed. Finally, the fear arose among the militia leaders broadly that some emigrants white men could get to see and would as likely to find out that the attackers, as well as themselves, not only Indians, but that their attackers from whites passed. This resulted in an order to kill all emigrants except young children.

Murders and aftermath of the massacre

Four of the nine militiamen of the Nauvoo Legion of the Tenth Regiment “Iron Brigade” indicted in 1874 with murder or conspiracy. ( Not shown: William H. Dame • William C. Stewart • Ellott Willden • Samuel Jukes • George Adair, Jr.)

Major John D. Lee, constable, judge, Indian agent . The only convicted participant, Lee, has plotted in advance with his immediate commander, Isaac C. Haight. He led the initial attack and falsely offered the emigrants safe passage before their kilometer-long march on the field of the massacre.

Philip Klingensmith, a Latter Day Saints Church (LDS) bishop and a private in the militia. He took part in the murders. After leaving the LDS Church, he later turned on his co-conspirators as a key witness .

On Friday, September 11, 1857, two militiamen with a white flag approached the Baker Fancher Party car and were soon followed by Indian agent and militia officer John D. Lee. Lee told the emigrants, tired from the fighting, that he had negotiated a truce with the Paiute Indians that would allow them to be escorted safely the 58 km back to Cedar City under the protection of the Mormons if they could get all of their cattle and supplies in return given to Native Americans. When the emigrants had accepted them, they were led out of their fortifications or their wagons, with the grown men separated from the women and children. The men were paired with a militia escort.

When a signal was given, the militiamen turned and shot the male members of the Baker Fancher Party standing by their side. The women and children were then ambushed and killed by other militias hiding in the nearby bushes and ravines. The militia members were pledged to secrecy and a plan was worked out to blame the Native American people for the massacre. The militia deliberately did not kill some of the young children because they were believed to be too young to tell the story later. These 17 children were initially taken in by local Mormon families, but were later reclaimed by the US Army and returned to relatives in Arkansas.

Leonard J. Arrington (1917–1999), founder of the Mormon History Association (MHA), reported that Brigham Young received rider James Haslam in his office that same day. When he learned what was being considered by the militia leaders in Parowan and Cedar City, he sent back a letter saying that they should not interfere in the affairs of the Baker Fancher Party and let them go in peace (although he acknowledged that Native Americans would likely "do as they please"). Young's letter arrived two days late on September 13, 1857.

Some of the dead’s property was reportedly stolen by the Indians involved, while large quantities of their valuables and livestock were stolen by the Mormons in southern Utah, including a. also by John Samuel Lee. Some of the cattle were brought to Salt Lake City and sold or traded. The remaining personal belongings from the Baker Fancher Party were taken to the Cedar City Tithe House and auctioned off to local Mormons.

Investigations and Law Enforcement

In an early investigation conducted by Brigham Young, John Samuel Lee was interviewed on September 29, 1857. In 1858 Young sent a report to the Indian Affairs Commissioner stating that the massacre was the work of Indians. The Utah War of 1857/58 delayed any investigation by the US federal government until 1859, when Jacob Forney (1829-1865) and US Army Brevet Major James Henry Carleton (1814-1873) began investigations. During his research, Carleton found women's hair in Mountain Meadows tangled in bushes of sage and the bones of children still in their mothers' arms. Carleton later said this was "a sight that can never be forgotten". After collecting the deceased's skulls and bones, Carleton's troops buried them and erected a cairn with a cross on it.

Carleton interviewed some local Mormon settlers and Paiute Indian chiefs and concluded that Mormons were involved in the massacre. In May 1859 he issued a report to the Assistant Adjutant-General of the United States in which he set out his findings. Jacob Forney, Utah Superintendent of Indian Affairs, also conducted an investigation visiting the area of the massacre in the summer of 1859. It was also he who picked up many of the surviving children of the massacre victims, who were housed with Mormon families, to assemble them in preparation for being transported back to their relatives in Arkansas. Forney concluded that the Paiutes did not act alone and that the massacre would not have happened without the white settlers, while Carleton, in his report to the US Congress, described the mass killings as a "heinous crime" and described both local and senior church leaders blamed for the massacre.

A federal judge brought to the Territory after the Utah War, Judge John Cradlebaugh , convened a grand jury in Provo in March 1859 regarding the massacre, but the jury dismissed any charges. Even so, Cradlebaugh took a military escort to see the Mountain Meadows area to see for himself. Cradlebaugh attempted to arrest John Samuel Lee, Isaac Haight, and John Higbee, but the men had already escaped before they could be found. Cradlebaugh publicly accused Brigham Young as the instigator of the massacre and thus as an "accessory before the fact" (German: "accomplice before the act"). "

Possibly as a safeguard against the suspicious federal judicial system, Mormon territorial probate judge Elias Smith arrested Young on a territorial warrant, perhaps in hopes of redirecting Young's trial to a friendlier Mormon territorial court. Since no federal indictment appeared to have been brought, Young was released.

Further investigations, interrupted by the American Civil War in 1861, resumed in 1871 when the prosecution received an affidavit from militia member Philip Klingensmith (1815 - circa 1881).

Klingensmith had been bishop of the Latter-day Saint Movement and blacksmith of Cedar City; however, by the 1870s, he had left The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) and moved to Nevada .

Lee was arrested on November 7, 1874 Dame, Philip Klingensmith and two others (Ellott Willden and George Adair, Jr.) were charged and arrested while warrants were obtained for the arrest of four others (Haight, Higbee, William C. Stewart and Samuel Jukes) who went into hiding. Klingensmith escaped prosecution by agreeing to testify.

Brigham Young removed some participants, including Haight and Lee, from the LDS Church in 1870. The US suspended bounties of $ 500 each (around $ 10,109 as of 2020) for the arrests of Haight, Higbee and Stewart , while prosecutors decided not to pursue their cases against Dame, Willden and Adair.

Lee's first trial began in Beaver on July 23, 1875, before a jury of eight Mormons and four non-Mormons. One of Lee's defense lawyers was former Utah Supreme Court Justice Enos D. Hoge (1831-1912). This process led to a “hung jury” or “deadlocked jury” of the jury on August 5, 1875, which means that the jury was unable to come to an agreement even after lengthy deliberation and was unable to do so required unanimous judgment. Lee's second trial began on September 13, 1876, before an all-Mormon jury. The prosecution called Daniel Wells, Laban Morrill, Joel White, Samuel Knight, Samuel McMurdy, Nephi Johnson and Jacob Hamblin .

Against the advice of attorneys, Lee agreed that the prosecution could reuse the testimony of Young and Smith from the previous trial. Lee did not call any witnesses in his defense. Lee did not call any witnesses in his defense at the trial, but this time he was convicted.

If Lee was convicted, as required by Utah Territory law, he was allowed to choose the method of his own execution from hanged, shot, or beheaded; Lee chose to be shot. Shortly before he was executed by firing squad in Mountain Meadows on March 23, 1877, Lee confessed that he was a scapegoat for the others involved. Brigham Young stated that Lee's fate was just, but was not sufficient atonement given the enormity of the crime .

Criticism and analysis of the massacre

Media coverage of the event

The first published report of the incident was written in 1859 by Carleton, who was hired by the US Army to investigate the incident and bury the still-exposed bodies in Mountain Meadows. Although the massacre was reported to some extent in the media during the 1850s, the first phase of intensive nationwide public relations work about the massacre did not begin until around 1872, after investigators received Klingenschmied's confession. In 1867, C. V. Waite published An Authentic Brigham Young Story describing the events. In 1872, Mark Twain commented on the massacre through the lens of contemporary American public opinion in an appendix to his semi-autobiographical travel book Roughing It . In 1873, the massacre was a prominent feature in the history of T.B. H. Stenhouse (1825–1882), The Rocky Mountain Saints . The national newspapers reported extensively on the Lee trials from 1874 to 1876, and his 1877 execution was also extensively covered.

The massacre has been extensively covered in several historical works, beginning with Lee's own 1877 confession , in which he expressed his opinion that Brigham Young sent George A. Smith to southern Utah to direct the massacre.

In 1910 the massacre was the subject of a short book by Josiah F. Gibbs, who also attributed responsibility for the massacre to Young and Smith. The first detailed and comprehensive work to use modern historical methods was The Mountain Meadows Massacre in 1950 by Juanita Brooks (1898–1989), a Mormon scholar who lived near the southern Utah area. Brooks found no evidence of direct involvement from Brigham Young, but accused him of obstructing the investigation and provoking the attack through his rhetoric.

At first, the LDS Church denied any involvement by Mormons and remained relatively silent on the matter. In 1872 she excommunicated some of the participants for their role in the massacre. Since then, the LDS Church has condemned the massacre and recognized the involvement of local Mormon leaders. In September 2007, the LDS Church published an article in its publications referring to the tragedy 150 years ago.

Historical theories explaining the massacre

Historians have attributed the massacre to a number of factors, including militant Mormon teachings in the years leading up to the massacre, the war hysteria, and the alleged involvement of Brigham Young.

Controversial Mormon Teachings

For the decade prior to the arrival of the Baker Fancher Party, the Utah area existed as a “theodemocracy” under the leadership of Brigham Young. In the mid-1850s, Young instituted a Mormon Reformation aimed at "putting the ax to the root of the tree of sin and iniquity." In January 1856, Young said, "[that] the government of God as administered here" may appear "despotic" to some because "... the judgment is pronounced against the violation of God's law."

In addition, the religion had seen a period of intense religious persecution in the United States Midwest in the preceding decades , and devout Mormons moved west to avoid persecution in the cities of the Midwest. In particular during the Mormon War of 1838 (between Mormons and non-Mormons, hence the Missouri Mormon War ), during which the prominent Mormon Apostle David W. Patten (1799-1838) was killed in battle, they were officially expelled from the state of Missouri . After the Mormons moved to Nauvoo, Illinois, founder Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum Smith were killed by an angry armed mob in Carthage Prison on June 27, 1844 while awaiting trial .

Just months before the Mountain Meadows massacre, Mormons learned that another apostle had been killed. On May 13, 1857, the Apostle Parley P. Pratt (1807-1857) was shot in Arkansas by Hector McLean, the estranged husband of Eleanor McLean Pratt, one of Pratt's polygamous wives . Parley Pratt and Eleanor went to the theocratic law of the Utah Territory, a so-called Celestial marriage (German: heavenly marriage ), but Hector had Eleanor refuses to divorce. “When she left San Francisco , she left Hector, and later she was due to declare in court that she had left him as a wife the night he evicted her from her home. Regardless of the legal situation, she considered herself an unmarried woman. "

Mormon leaders immediately proclaimed Pratt another martyr , with Brigham Young declaring, "Since the death of Joseph, nothing has happened that I have found it difficult to reconcile," and many Mormons held the Arkansas people responsible. "It was Mormon policy to hold every Arcane man accountable for Pratt's death, just as every Missourian was hated for driving the Church out of this state."

Mormon leaders taught that the second coming of Jesus was imminent - "... there are those now living on earth who will see consummation" and "... we now testify that his coming is at hand."

Based on a somewhat ambiguous statement by Joseph Smith, some Mormons believed that Jesus would return in 1891 and that God would soon punish the United States for the persecution of Mormons and the martyrdom of Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, David Patten, and Parley Pratt.

“It is a grave fact that the people of the United States have shed the blood of the prophets, cast out the saints of God, rejected the priesthood, and ruined the holy gospel; and the result of the rejection of the gospel in every age has been a visitation by the chastening hand of the Almighty - what punishment is given in proportion to the extent and gravity of their crimes. Therefore I expect the Lord to use his whip against the stubborn son named "Uncle Sam"; "

At their foundation ceremony, early Saints of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints took an oath to pray that God would take vengeance on the murderers. As a result of this oath, several Mormon apostles and other leaders considered it their religious duty to kill the murderers of the prophets if they should ever meet them.

The sermons, blessings, and private advice given by Mormon leaders shortly before the Mountain Meadows Massacre can be understood as encouraging individuals to carry out God's judgment against the wicked. Church leaders' teachings were particularly harsh in Cedar City, where the Mormons were taught that members should ignore dead bodies and go about their business.

Colonel William H. Dame, the senior officer in southern Utah who commanded the Mountain Meadows Massacre, received the patriarchal blessing in 1854 that he was "at the head of part of your brothers and the Lamanites (Native Americans) for the redemption of Zion and the Vengeance of the blood of the prophets on those who dwell on the earth ”would be called. In June 1857, Philip Klingensmith, another contributor, was similarly blessed to be part of "Revenge of the Blood of Brother Joseph".

For example, historians argue that the Mormons in southern Utah were particularly affected by an unsubstantiated rumor that the Baker-Fancher wagon train was joined by a group of eleven miners and plainsmen, some of whom were allegedly called the Missouri Wildcats Taunted and vandalized Mormons and Indians along the route and "caused trouble" (according to some allegations, they owned the gun that "shot Old Joe Smith the guts out.")

They were also struck by the report to Brigham Young that the Baker Fancher party was from Arkansas, where Parley was. P. Pratt was murdered. It was rumored that Pratt's wife recognized some members of the Mountain Meadows Party as members of the gang that shot and stabbed Pratt.

War hysteria

The Mountain Meadows massacre was caused in part by events related to the Utah War , an 1857 United States Army deployment to the Utah Territory, the arrival of which was peaceful. However, in the summer of 1857, the Mormons expected a total invasion of apocalyptic importance. From July to September 1857, the Mormon leaders and their supporters prepared for a siege that could have ended similarly to the Bleeding Kansas problem of 1854-61. The Mormons were required to store grain and were instructed not to sell grain to emigrants for fodder. As the far-flung Mormon colonies retreated, Parowan and Cedar City became isolated and vulnerable outposts. Brigham Young tried to enlist the help of the Indian tribes in the fight against the "Americans" by encouraging them to steal cattle from migrant trains and to join the Mormons in the fight against the approaching army.

Scholars claimed that George A. Smith's journey through southern Utah influenced the decision to attack and destroy the Fancher-Baker emigrant train near Mountain Meadows, Utah. He met with many of the later participants in the massacre, including William H. Dame, Isaac Haight, John D. Lee, and Chief Jackson, the leader of a group of Paiutes. He noted that the militias were organized and ready to fight, and that some of them were eager to “fight and take revenge for the atrocities inflicted on us in the States”.

Smith's party included some Paiute Indian chiefs from the Mountain Meadows area. When Smith returned to Salt Lake City, Brigham Young met these chiefs on September 1, 1857, and encouraged them to fight the Americans in the expected clash with the United States Army. They were also offered all the cattle en route to California at the time, including those from the Baker Fancher Party. The Native American chiefs hesitated, and at least one chief objected to the offer, having previously been told not to steal and declined the offer.

Brigham Young

Historians agree that Brigham Young played a role, at least unknowingly, in provoking the massacre and in obscuring the evidence afterwards. However, they debate whether Young knew about the planned massacre in advance and whether he initially tacitly tolerated it before later publicly speaking out against it. The inflammatory and violent language Young used in response to the federal government's expedition contributed to the tense atmosphere at the time of the attack. After the massacre, Young stated on public forums that God had taken vengeance on the Baker Fancher Party. It is unclear whether Young took this view because he believed this particular group posed an actual threat to the colonists, or because he believed the group was directly responsible for previous crimes against Mormons. However, in the only known correspondence that Young wrote prior to the massacre, he told Church leaders in Cedar City:

“As for the emigration trains that pass through our settlements, we must not obstruct them until they are first notified to stay away. You mustn't interfere with them. The Indians whom we expect to do what they want; but you should try to keep them comfortable. There are no other trains going south that I know of. If those who are there will go, let them go in peace. "

Says the historian MacKinnon: “After the [Utah] war, US President James Buchanan indicated that face-to-face communication with Brigham Young could have averted the conflict, and Young argued that a north-south telegraph line in Utah was responsible for the massacre of Mountain Meadows could have prevented. ”MacKinnon suggested that the hostilities could have been avoided if Young had traveled east to Washington DC to solve problems with the government, rather than a five-week trip on the eve of the Utah War for church reasons to undertake in the north.

A modern forensic assessment of an important affidavit allegedly made by William Edwards in 1924 has complicated the debate over the complicity of high-level Mormon leadership in the Mountain Meadows Massacre. The analysis suggested that Edwards' signature might be traceable and that the typesetting belonged to a typewriter made in the 1950s. The Utah State Historical Society, which keeps the document in its archives, admits a possible connection to Mark Hofmann (* 1954), a convicted forger and extortionist through the intermediary of Lyn Jacobs, who made the document available to the society.

Memorials

The first memorial to the victims was erected two years after the massacre of Major Carleton and the United States Army. This memorial was a simple pile of stones erected over the grave of 34 victims and topped with a large red cedar cross . When the memorial was found destroyed, Captain Geo F. Price of the U.S. Army had the structure replaced in 1864. According to some reports, the memorial was destroyed in 1861 when Young brought an entourage to Mountain Meadows. Wilford Woodruff , who later became the fourth President of the LDS Church, claimed as he read the inscription on the cross that "Vengeance is mine, thus saith the Lord". "I'll pay it back," Young replied, "the vengeance should be mine, and I've taken a little." In 1932, residents of the area built a memorial wall around the remains of the monument.

From 1988 the Mountain Meadows Association - made up of descendants of the victims of the Baker Fancher Party, as well as Mormon participants - designed a new memorial in Meadows; this memorial was completed in 1990 and is maintained by the Utah State Division of Parks and Recreation . In 1999, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints replaced the U.S. Army cairn and memorial wall from 1932 with a second memorial it now maintains. When the LDS Church began building the memorial in August 1999, the remains of at least 28 other victims of the massacre were discovered and excavated while an excavator was being used. Forensic evidence from examining the remains of the men revealed that they had been shot at close range with firearms and that the remains of the women and children showed signs of trauma from blunt force.

In 1955, a memorial was erected in Harrison Town Square, Arkansas , to commemorate the victims of the massacre . On one side of this memorial is a map and a brief summary of the massacre, while the opposite side has a list of the victims.

In 2005, a replica of the original US Army cairn from 1859 was erected in Carrollton, Arkansas; it is maintained by the Mountain Meadows Massacre Foundation of the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation (MMMF).

The 150th anniversary of the massacre in 2007 was celebrated with a ceremony in Mountain Meadows, attended by about 400 people, among others. a many descendants of those murdered in the massacre, as well as the elder of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the LDS Church, Henry B. Eyring .

In 2011 the site was designated as a National Historic Landmark following joint efforts by the descendants of the murdered and the LDS Church .

In 2014, archaeologist Everett Bassett discovered two piles of stones that he believes mark additional graves. The locations of the possible graves are on private land and not on one of the grave sites owned by the LDS Church. The Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation has expressed its desire that the sites be preserved and given national monument status. However, other groups of descendants were more reluctant to accept the sites as legitimate burial sites.

List of all those killed and surviving the massacre

List of killed children and adolescents under the age of 18

| First name | Surname | Age | First name | Surname | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mary Lovina | Baker | 7 years | America Jane | Dunlap | 7 years |

| Melissa Ann | Beller | 14 years | William | Fancher | 17 years |

| David W. | Beller | 12 years | Mary | Fancher | 15 years |

| Henry | Cameron | 16 years | Thomas | Fancher | 14 years |

| James | Cameron | 14 years | Martha | Fancher | ten years |

| Martha | Cameron | 11 years | Sarah G. | Fancher | 8 years |

| Larkin | Cameron | 8 years | Margaret A. | Fancher | 8 years |

| Nancy | Cameron | 12 years | John | Huff | 14 years |

| Nancy M. | Dunlap | 16 years | William C. | Huff | 13 years |

| James D. | Dunlap | 14 years | Mary E. | Huff | 11 years |

| Lucinda | Dunlap | 12 years | James K. | Huff | 8 years |

| Susannah | Dunlap | 12 years | (unknown) | Huff | 6 years |

| Margarette | Dunlap | 11 years | Sophronia | Jones | 4 years |

| Mary Ann | Dunlap | 9 years | James William | Miller | 9 years |

| Thomas Jesse | Dunlap | 17 years | John | Mitchell | (Child) |

| John H. | Dunlap | 16 years | Matilda | Tackitt | 16 years |

| Mary Ann | Dunlap | 13 years | James M. | Tackitt | 14 years |

| Talitha Emaline | Dunlap | 11 years | Jones M. | Tackitt | 12 years |

| Nancy | Dunlap | 9 years |

List of killed women aged 18 and over

| First name | Surname | Age | First name | Surname | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manerva A. Bella | Baker | 25 years | Eloah Angeline | Tackitt Jones | 26 years |

| Martha | Cameron | 51 years | Matilda | Cameron Miller | 26 years |

| Mary Wharton | Dunlap | 39 years | Sarah C. | Baker Mitchell | 21 years |

| Ellender | Dunlap | 18 years | Cynthia | Tackitt | 49 years |

| Eliza Ingram | Fancher | 42 years | Marion | Tackitt | 20 years |

| Saleta Ann | (Brown) Huff | 36 years | Amilda | Miller Tackitt | 22 years |

| Elisha | Huff | (?) |

List of killed men aged 18 and over

| First name | Surname | Age | First name | Surname | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William Aden | Everyone | 51 | Robert | Fancher | 19 years |

| George Washington | Baker | 57 | John Milum | Jones | 32 years |

| John Twitty | Baker | 52 | Newton | Jones | 23 years |

| Abel | Baker | 19 years | Lawson A. | McIntire | 21 years |

| John | Beach | 21 years | Josiah (Joseph) | Miller | 30 years |

| William | Cameron | 51 years | Charles R. | Mitchell | 25 years |

| Tillman | Cameron | 21 years | John D. | Mitchell | 23 years |

| Isom | Cameron | 18 years | John | Prewitt | 20 years |

| Allen P. | Deshazo | 20 years | William | Prewitt | 18 years |

| Jesse | Dunlap Jr. | 39 years | Milum L. | Rush | 28 years |

| Lorenzo Law | Dunlap | 49 years | Se (a) bron | Tackitt | 18 years |

| William M. | Eaton | (?) | Pleasant | Tackitt | 25 years |

| Silas | Edwards | 26 years | Richard | Wilson | (?) |

| Alexander | Fancher | 45 years | Solomon R. | Wood | 20 years |

| James Matthew | Fancher | 25 years | William | Wood | 26 years |

List of surviving children

| First name | Surname | Age | First name | Surname | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mary Elizabeth | Baker | 5 years | Triphenia D. | Fancher | 22 months |

| Sarah Frances | Baker | 3 years | Nancy Saphrona | Huff | 4 years |

| William Twitty | Baker | 9 months | Felix Marion | Jones | 18 months |

| Georgia Ann | Dunlap | 18 months | John Calvin | Miller | 6 years |

| Louisa | Dunlap | 4th | Joseph | Miller | 1 year |

| Prudence Angeline | Dunlap | 5 years | Mary | Miller | 4 years |

| Rebecca J. | Dunlap | 6 years | Emberson Milum | Tackitt | 4 years |

| Sarah E. | Dunlap | 1 year | William Henry | Tackitt | 19 months |

| Christopher "Kit" Carson | Fancher | 5 years |

Media reporting on the massacre

- Massacre at Mountain Meadows , by Ronald W. Walker (1939-2016), Richard E. Turley and Glen M. Leonard (2008)

- House of Mourning: A Biocultural History of the Mountain Meadows Massacre , by Shannon A. Novak (2008)

- September Dawn by Christopher Cain (2007)

- Burying The Past: Legacy of The Mountain Meadows Massacre , documentary by Brian Patrick (2004)

- American Massacre: The Tragedy At Mountain Meadows, September 1857 , by Sally Denton (2003)

- Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows , by Will Bagley (2002)

- The Mountain Meadows Massacre , by Juanita Brooks (1950)

- Red Water , novella by Judith Freeman (2002)

- Godless (TV Series) Netflix Miniseries, Episode 2, (2017)

See also

bibliography

- Richard Abanes: One Nation Under Gods: A History of the Mormon Church . Ed .: Basic Books. 2003, ISBN 1-56858-283-8 , pp. 672 (English, mrm.org ).

- Bagley, Will, and David L. Bigler: Innocent Blood: Essential Narratives of the Mountain Meadows Massacre . Ed .: The Arthur H. Clark Company. Norman, Oklahoma 2008, ISBN 978-0-87062-362-2 , pp. 508 ( google.de [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Will Bagley: Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows . Ed .: University of Oklahoma Press. tape 62 , no. 1 , 2002, p. 159-166 , JSTOR : 43044339 (English).

- Hubert Howe Bancroft: The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: History of Utah, 1540–1886 . Ed .: History Company. tape 26 , 1889 (English, archive.org ).

- John Hanson Beadle: Life in Utah, or, The mysteries and crimes of Mormonism: Being an exposé of the secret rites and ceremonies of the Latter-Day Saints, with a full and authentic history of polygamy and the Mormon sect from its origin to the present time . National Publishing, 1870, Chapter VI. The Bloody Period, S. 177–195 (English, Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- Robert H. Briggs: The Mountain Meadows Massacre: An Analytical Narrative Based on Participant Confessions , 2006, Utah Historical Quarterly, Volume 74, Issue 4, pp. 313 ff OCLC 367763056

- Juanita Brooks: The Mountain Meadows Massacre . Ed .: University of Oklahoma Press. Norman 1962, ISBN 0-8061-2318-4 , pp. 352 (English, google.de [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Los Angelas Star (Ed.): Rumored Massacre on the Plains . tape 8 , no. 21 . Los Angeles October 3, 1857 (English, unl.edu [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Frank J. Cannon, George L. Knapp: Brigham Young and His Mormon Empire . Fleming H. Revell Co., New York 1913, p. 273–283 (English, Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- James Henry Carleton: Special Report of the Mountain Meadow Massacre 1859 . Ed .: United States Government Publishing Office. 1902, p. 40 (English, archive.org [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Albert Carrington: The Court & the Army . Ed .: Deseret News. tape 9 , no. 5 , April 6, 1859, p. 2 (English, utah.edu [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- J. Ward Christian: Horrible Massacre of Arkansas and Missouri Emigrants (Letter to GN Whitman) . Ed .: Los Angeles Star. Los Angeles October 4, 1857 (English, sidneyrigdon.com [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- John Cradlebaugh: Charge (Presented orally by the Hon. John Cradlebaugh to the Grand Jury, Provo, Tuesday, March 8, 1859) [Content hosted at the J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah] . Editor: Valley Tan. tape 1 , no. 20 , March 15, 1859, p. 1 (English, utah.edu [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- John Cradlebaugh: Discharge of the Grand Jury [content hosted at the J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah] . Editor: Valley Tan. tape 1 , no. March 22 , 29, 1859 (English, utah.edu [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- John Cradlebaugh: Utah and the Mormons: a Speech on the Admission of Utah as a State . In: 37th United States Congress, 3rd Session . February 7, 1863 (English, loc.gov [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Robert D. Crockett: A trial lawyer reviews Will Bagleys' Blood of the Prophets . Ed .: FARMS Review (= 2 ). Volume 15 edition. 2003, p. 199–254 (English, byu.edu [PDF; accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Forrest S. Cuch: The History Of Utahs American Indians . Ed .: Utah State Division of Indian Affairs, Utah State Division of History, Utah State University Press. Salt Lake City 2003, ISBN 0-913738-49-2 , The Paiute Tribe of Utah, The Mountain Meadows Massacre, pp. 131–139 , JSTOR : j.ctt46nwms (English, archive.org [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Sally Denton: American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, September 1857 . Ed .: Alfred A. Knopf. New York 2004, ISBN 0-375-72636-5 , pp. 3006 (English, google.li [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Jacob Piatt Dunn: Massacres of the Mountains: A History of the Indian Wars of the Far West . Ed .: Harper & Brothers. New York 1886, p. 808 (English, archive.org [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Dan Erickson: Joseph Smith's 1891 Millennial Prophecy: The Quest for Apocalyptic Deliverance . In: University of Illinois Press, Mormon History Association (Ed.): Journal of Mormon History . tape 22 , no. 2 , 1996, p. 1-34 , JSTOR : 23287437 (English).

- James Finck: Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture . Ed .: Encyclopedia of Arkansas Project. Little Rock, Arkansas 2018 ( encyclopediaofarkansas.net [accessed July 29, 2020]).

- Alyssa Fisher: A Sight Which Can Never Be Forgotten . Ed .: Archaeological Institute of America. September 16, 2003 (English, archeology.org [accessed July 29, 2020] Journal).

- J. Forney: Kirk Anderson Esq . Editor: Valley Tan. May 10, 1859 (English, utah.edu [accessed July 29, 2020]).

- J [acob] Forney: Visit of the Superintendent of Indian Affairs to Southern Utah . Ed .: Deseret News (= 10 ). Volume 9 edition. May 11, 1859, p. 1 (English, utah.edu [accessed July 29, 2020]).

- Sarah Barringer Gordon; Jan Shipps: Fatal Convergence in the Kingdom of God: The Mountain Meadows Massacre in American History . Ed .: Journal of the Early Republic. 2017, p. 1–41 (English, iupui.edu [PDF; accessed July 29, 2020]).

- Jedediah M. Grant: Discourse . Ed .: Deseret News (= 22 ). Volume 4 edition. March 12, 1854, p. 1–2 (English, archive.today [accessed July 29, 2020]).

- Jacob Hamblin: Mountain Meadows Massacre Trials (John D. Lee Trials) 1875-1876, Testimony of Jacob Hamblin. In: University of Missouri-Kansas City, School of Law. 1876, accessed July 29, 2020 .

- Dimick B. Huntington: 1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre Journals . LDS Archives 1857 (English, mtn-meadows-assoc.com [accessed July 29, 2020]).

- Heber C. Kimball: Journal of Discourses . Ed .: S. W. Richards. Volume 4 edition. Aug 16, 1857, Limits of Forebearance — Apostates — Economy — Giving Endowments, p. 374–376 ( byu.edu [accessed July 29, 2020]).

- Heber C. Kimball: Journal of Discourses Delivered by President Brigham Young, His Two Counselors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others . Ed .: Amasa Lyman. Volume 4 edition. Liverpool 28 August 1859, p. 231–237 (English, byu.edu [accessed July 29, 2020]).

- Philip Klingensmith: Testimony of Philip J Klingensmith in the First trial of John D. Lee. Mountain Meadows Association, July 24, 1875, accessed July 27, 2020 .

- John D. Lee: Mormonism Unveiled; or the Life and Confessions of the Late Mormon Bishop, John D. Lee . Ed .: Bryan, Brand & Co., St. Louis, Missouri. 1877 (English, archive.org [accessed July 29, 2020]).

- William Alexander Linn: The Story of the Mormons: From the Date of their Origin to the Year 1901 . Ed .: Macmillan, New York. 1902 (English).

- William P. MacKinnon: Loose in the stacks, a half-century with the Utah War and its legacy (= 1 ). Volume 40 edition. 2007, p. 43–81 (English, archive.org [PDF; accessed July 29, 2020]).

- Laban Morrill: Laban Morrill Testimony — Witness for the Prosecution at Second Trial of John D. Lee September 14 to 20, 1876 (Mountain Meadows Massacre Trials (John D. Lee Trials) 1875-1876) . Ed .: The Mountain Meadows Association. September 1876 (English, archive.org [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Shannon Novak, Lars Rodseth: Remembering Mountain Meadows: Collective violence and manipulation of social boundaries . In: Journal of Anthropological Research . tape 62 , no. 1 . The University of Chicago Press, 2006, ISSN 0091-7710 , pp. 1-25 , doi : 10.3998 / jar.0521004.0062.101 , JSTOR : 3630719 .

- Charles W. Penrose & James Holt Haslam: Supplement to the lecture on the Mountain Meadows massacre. Important additional testimony recently received . Ed .: Printed at Juvenile Instructor Office. Salt Lake City 1885, p. 40 (English, archive.org [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Steven Pratt: Eleanor McLean and the Murder of Parley P. Pratt . Ed .: BYU Studies (= 2 ). Volume 15 edition. Salt Lake City 1975, p. 1–29 (English, byu.edu [PDF; accessed July 30, 2020]).

- D. Michael Quinn: The Mormon Hierarchy: Extensions of Power . Ed .: Signature Books. Salt Lake City 1997, ISBN 978-1-56085-060-1 (English).

- D. Michael Quinn: LDS 'Headquarters Culture' and the Rest of Mormonism: Past and Present . Ed .: Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought (= 3–4 ). Volume 34 edition. 2001, p. 135–164 (English, dialoguejournal.com [PDF; accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Malinda (Cameron) Scott Thurston Deposition & Malinda Thurston, v. United States and Ute Indians. In: mtn-meadows-assoc.com (English) Ed. Mountain Meadows Association (accessed July 30, 2020)

- Gene Sessions: Shining New Light on the Mountain Meadows Massacre (2003 FairMormon Conference). Foundation for Apologetic Information & Research (FAIR), 2003, accessed July 30, 2020 .

- George A. Smith: Deposition, People v. Lee . Ed .: Deseret News (= 27 ). Volume 24 edition. Salt Lake city Aug. 4, 1875, p. 1 (English, utah.edu [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Mark Twain: Roughing It . Ed .: American Publishing. Hartford, Connecticut 1873 (English, archive.org [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Catharine Van Valkenburg Waite: The Mormon Prophet and His Harem: Or, an Authentic History of Brigham Young, His Numerous Wives and Children . Ed .: JS Goodman & Co. Chicago 1868 (English, archive.org [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, Orson Hyde, Parley P. Pratt, William Smith (Latter Day): Proclamation of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints . The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1845 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Brigham Young: Deposition, People v. Lee . Ed .: Deseret News. June 25, 1889 (English, utah.edu [accessed July 30, 2020]).

- Josiah F. Gibbs: The Mountain Meadows Massacre . Ed .: Utah Lighthouse Ministry. 1910 (English, utlm.org [accessed July 30, 2020]).

Web links

- Mountain Meadows Massacre, Utah, United States, 1857. In: britannica.com (English)

- Mountain Meadows Association. In: mtn-meadows-assoc.com (English)

- Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation. In: web.archive.org (English)

- PBS Frontline documentary: The Mormons, Part One, episodes 8 & 9: Mountain Meadows. In: pbs.org (English)

- The Mountain Meadows Massacre: A Bibliographic Perspective by Newell Bringhurst. In: signaturebookslibrary.org (English)

- United States Office of Indian Affairs papers relating to charges against Jacob Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Utah Territory, Yale Collection of Western Americana, beincke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. In: archives.yale.edu (English)

- Mountain Meadows Massacre Victims & Members. In: legendsofamerica.com (English)

- The massacre on September 11, 1857, by Uwe Schmitt, September 10, 2007. In: welt.de

- September 11th, a black day in the memory of Mormons. In: by Manfred Trozka, April 29, 2007. In: sektenausstieg.net

- The Juanita Brooks Lecture Series, The 26th Annual Lecture, Revisting the Mssacre at Mountain Meadows, by Glen M. Leonhard, March 18, 2009, 44 pp. In: library.dixie.edu (English, PDF) , (accessed on 29. July 2020)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b The Nauvoo Legion was a state-authorized militia of the city of Nauvoo in Illinois in the USA. With the growing contradiction of the surrounding settlements, the defense of Nauvoo and the surrounding settlement areas became the main task for the Latter Day Saint movement (German: Movement of Latter-day Saints ). After the Nauvoo Charter was repealed in 1844, the members of the Nauvoo Legion continued to work under the command of Brigham Young, leader of the movement's largest faction, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church for short). Young led the Latter-day Saints from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the Great Salt Flat in the area that later became the Territory of Utah from February 1846 to the summer of 1847. In Utah, the Deseret Militia and the Utah Territorial Militia used the official name of the Nauvoo Legion.

- ^ The 17 Children who survived the 1857 Mountain Meadows Masscre. In: mtn-meadows-assoc.com (English)

- ↑ The war hysteria was partly attributed to events related to the Utah War from May 1857 to July 1858, an armed confrontation between the United States Army and Mormon settlers in the territory of Utah.

- ↑ For the ten years prior to the arrival of the emigrants, the Utah Territory had existed as a theocracy led by Brigham Young. As part of Young's vision of a “Kingdom of God” before the turn of the millennium, Young established colonies along the California Trail and the Old Spanish Trail where Mormon officials ruled as leaders of church, state, and military.

- ↑ The Mormon Reformation was a time of renewed emphasis on spirituality in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). It took place in 1856–57 and was directed by Church President Brigham Young.

- ↑ 1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre, Arkansas Emigrants - Families. In: mtn-meadows-assoc.com (English)

- ^ CPT Alexander Fancher. In: Find A Grave

- ↑ Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, by Will Bagley, University of Oklahoma Press: Norman 2002 in the Google Book Search USA

- ^ The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: History of Utah. 1889, by Hubert Howe Bancroft in the Google Book Search USA

- ↑ Shirts, (1994) Paragraph 2

- ^ A b Morris A. Shirts: Mountain Meadows Massacre. In: Utah History Encyclopedia. University of Utah Press, 1994, accessed July 24, 2020 .

- ↑ George A. Smith, Apostle, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In: geni.com (English)

- ↑ George Albert Smith. In: Find A Grave

- ↑ Thales Hastings Haskell. In: hirf.org (English)

- ↑ John Lyman Smith. In: Find A Grave (English)

- ↑ James A. Little: Jacob Hamblin: A Narrative of His Personal Experience Fifth Book of the Faith-Promoting Series (Chapter VI). In: Juvenile Instructor Office. 1881, accessed July 25, 2020 .

- ^ War with the Mormons in Missouri 1838. In: churchofjesuschrist.org

- ^ Brigham Young: Interview with Brigham Young. In: Deseret News, Volume 26, Issue April 16, 30, 1877, accessed on July 25, 2020 .

- ^ A b c James Henry Carleton: Special Report of the Mountain Meadow Massacre . Ed .: United States Government Publishing Office. 1902, OCLC 2759744 (English, archive.org [accessed July 25, 2020]).

- ↑ A stake is an administrative unit, which in certain denominations made up of several municipalities movement of Latter-day Saints (English: Latter Day Saint movement ) composed. The presiding officer in a stake is referred to as the stake president.

- ^ Shirts (1994), paragraph 6

- ^ A b The Mountain Meadows Association (ed.): Laban Morrill Testimony — Witness for the Prosecution at Second Trial of John D. Lee September 14 to 20, 1876 (Mountain Meadows Massacre Trials (John D. Lee Trials) 1875–1876) . September 1876 (English, mtn-meadows-assoc.com [accessed July 25, 2020]).

- ↑ Testimony of James Holt Haslam, Taken at Wellsville, Cach Count, Utah, December 4, 1884. In: mountainmeadows.unl.edu (English)

- ↑ Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley, JR., Glen M. Leonard: Massacre at Mountain Meadows . Ed .: Oxford University Press. 2008, p. 157 (English, archive.org [accessed July 25, 2020]).

- ↑ Shirts, 1994, paragraph 8

- ^ Charles W. Penrose: Supplement to the lecture on the Mountain Meadows massacre. Important additional testimony recently received . Ed .: Printed at Juvenile Instructor Office, Salt Lake City. 1885 (English, archive.org ).

- ^ A b c Brigham Young, by Leonard J. Arrington, University of Illinois Press in the Google Book Search USA

- ↑ Shirts, 1994 Paragraph 8

- ↑ Shirts, (1994) Paragraph 6

- ↑ Ronald W. Walker: Save the emigrants - Joseph Clewes on the Mountain Meadows massacre (Joseph Clewes - eyewitness - Statement) . In: BYU Studies . tape 42 , no. 1 , 2003 (English, byustudies.byu.edu ): "... it was announced by Higbee that the emigrants should be wiped out."

- ↑ Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley, Glen M. Leonard: Massacre at Mountain Meadows . Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 178–180 (English, Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Phil Konstantin: Mountain Meadows Massacre Site in Utah. In: americanindian.net. 2009, accessed on July 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Shirts, (1994) paragraph 9.

- ↑ Brooks, 1950, pp. 101-105.

- ^ Brigham Young to Isaac C. Haight, Sep 10, 1857, Letterpress Copybook 3: 827-28, Brigham Young Office Files, LDS Church Archives. In: fairmormon.org (English)

- ^ Philip Klingensmith: Mountain Meadows Massacre, Affidavit of Philip Klingensmith . Ed .: Corinne Journal Reporter, Volume 5, Issue 252, p. September 24, 1872, p. 1 (English, utah.edu [accessed July 26, 2020]).

- ↑ Forney 1859, p. 1.

- ^ A b c Alyssa Fischer: The Mountain Meadows Massacre A Sight Which Can Never Be Forgotten . In: Archaeological Institute of America. September 16, 2003, accessed July 26, 2020 .

- ↑ Forney 1859, p. 1

- ↑ Cradlebaugh 1859, p. 3; Carrington 1859, p. 2.

- ↑ a b c Bagley 2002, p. 225

- ↑ Bagley 2002, p. 226

- ^ Accessory before the fact. In: dictionary.thelaw.com A pre-crime accomplice is someone who encourages a person to commit a crime but may not be involved in the commission of the crime or be present at the time the crime is committed.

- ↑ Bagley 2002, p. 234

- ↑ Brooks 1950, p. 133

- ↑ Philip Klingensmith. In: Find a Grave

- ↑ Briggs 2006, p. 315

- ^ "John D. Lee Arrested," Deseret News , Nov. 18, 1874, p. 16.

- ^ Robert H. Briggs: Tragedy at Mountain Meadows Massacre: Toward a Consensus Account and Time Line . In: Dixie State College of Utah. July 26, 2011, accessed July 26, 2020 .

- ^ "The Lee Trial," Deseret News , July 28, 1875, p. 5.

- ^ Orson Ferguson Whitney, Popular History of Utah (1916), p. 305.

- ↑ Lee 1877, pp. 317-378.

- ↑ Lee 1877, pp. 302 f.

- ↑ Lee 1877, p. 378.

- ^ "Territorial Dispatches: the Sentence of Lee," Deseret News , October 18, 1876, p. 4.

- ↑ Lee 1877, p. 225 f.

- ^ Brigham Young: Interview with Brigham Young. In: Utah Digital Newspapers, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, The Deseret News. May 30, 1877, accessed July 26, 2020 . When asked by the interviewer if he believed in blood atonement, Young replied, "I do, and I believe Lee did not half atone for his great crime."

- ^ The Overland Journey from Utah to California: Wagon Travel from the City of Saints to the City of Angels, by Edward Leo Lyman, 2004, University of Nevada Press, ISBN 978-0874175011 in the Google Book Search

- ↑ Thomas B. H. Stenhouse: The Rocky Mountain Saints: a Full and Complete History of the Mormons, from the First Vision of Joseph Smith to the Last Courtship of Brigham Young . Ed .: D. Appleton. New York 1873, LCCN 16-024014 (English, google.com [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ↑ John D. Lee: Mormonism Unveiled; or the Life and Confessions of the Late Mormon Bishop . Bryan, Brand & Co., St. Louis, Missouri 1877 (English, archive.org ).

- ↑ John D. Lee: Mormonism Unveiled Or the Life and Confessions of the Late Mormon Bishop John D. Lee . Ed .: Kessinger Publishing. 2007, ISBN 978-0-548-19694-6 , pp. 404 (English, google.co.vi [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ^ Josiah Francis Gibbs: The Mountain Meadows Massacre . Ed .: Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City 1910, LCCN 37-010372 , p. 59 (English, google.com [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ^ Will Bagley, Blood of the prophets: Brigham Young and the massacre at Mountain Meadows . Ed .: University of Oklahoma Press. 2002, ISBN 0-8061-3639-1 , pp. 273 (English).

- ^ Richard E. Turley Jr .: The Mountain Meadows Massacr . Ed .: Ensign, LDS magazine. September 2007 (English, archive.org [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ↑ Michael De Groote: Writing Massacre at Mountain Meadows . Ed .: Mormon Times. February 21, 2009 (English, archive.org [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ↑ Theodemocracy is a theocratic political system promoted by Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter-day Saint Movement. According to Smith, a theodemocracy is an amalgamation of traditional republican democratic principles - according to the United States Constitution - with theocratic rule.

- ^ Brigham Young: The Powers of the Priesthood not Generally Understood - The Necessity of Living by Relvation - The Abuse of Blessings. Ed .: Brigham Young University. January 27, 1856 (English, archive.org [accessed July 28, 2020]): “Is the spirit of government and dominion here despotic? In their use of the word some may feel that way. It lays the ax to the root of the tree of sin and iniquity; The judgment is pronounced against breaking the law of God. If that is despotism, then the politics of this people can be seen as despotic. But doesn't the government of God, as administered here, give everyone their rights? "

- ^ Eleanor McLean Pratt: The Latter-Day Saints' Millennial Star . Ed .: Liverpool, S. W. Richards, 42, Islington. Volume 19, May 12, 1857, To the Honorable Judge of the Court, in the town of Van Buren, State of Arkansas, May 12, 1957 (Mrs. Pratt's Letter to the Judge), pp. 425-426 (English, google.com [accessed July 7, 2020]).

- ^ Eleanor McLean Pratt: The Latter-Day Saints' Millennial Star . Ed .: Liverpool, S. W. Richards, 42, Islington. Volume 19, May 12, 1857, Further Particulars of the Murder - To Brother Orson (A letter from Eleanor McLean Pratt), pp. 426-427 (English, google.com [accessed July 27, 2020]).

- ↑ Heavenly marriage (also known as the New and Eternal Covenant of Marriage) is a teaching that marriage in heaven can last forever. This is a unique teaching of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), or Mormonism and the Branches of Mormon Fundamentalism.

- ↑ Steven Pratt: Eleanor McLean and the Murder of Parley P. Pratt . In: Brigham Young University Studies . tape 15 , no. 2 , 1974, p. 233 , JSTOR : 43040559 (English): “When she left San Francisco she left Hector, and later she was to state in a court of law that she had left him as a wife the night he drove her from their home. Whatever the legal situation, she thought of herself as an unmarried woman. "

- ↑ A Friend Of The Oppressed: Murder of Parley P. Pratt, One of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints . Ed .: Brigham Young University (= The Latter-day Saints' Millennial Star, Vol. 19 ). July 4, 1857, p. 420-421 ( byu.edu [accessed July 27, 2020]).

- ^ I die a firm believer in the Gospel of Jesus Christ as revealed through the Prophet Joseph Smith. ... I know that the Gospel is true and that Joseph Smith was a prophet of the living God, I am dying a martyr to the faith. (German: I die in firm faith in the gospel of Jesus Christ, as it was revealed through the Prophet Joseph Smith. ... I know that the gospel is true and that Joseph Smith was a prophet of the living God, I am dying as a martyr of Faith.) The Extraordinary Life of Parley P. Pratt. In: churchofjesuschrist.org , accessed July 27, 2020

- ↑ Brooks 1950, p. 36 f.

- ↑ Linn (1902) p. 519 f.

- ↑ The Second Coming (sometimes referred to as Second Advent or Parousia) is a Christian, Islamic, and Baháʼí belief regarding the return of Jesus after his ascension about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messianic prophecy and is part of most Christian eschatologies. (see en: Second Coming )

- ^ Young, Kimball, Hyde, Pratt 1845, pp. 2, 5

- ↑ Erickson, p. 9

- ↑ Jedediah M. Grant: Journal of Discourses . Ed .: F.D. & S. W. Richards, Liverpool, 1855. April 2, 1854, Fulfillment of Prophecy — Wars and Commotions, p. 148 (English, byu.edu [accessed July 27, 2020]).

- ^ The diary of Heber C. Kimball (1801–1868) (December 21, 1845); Beadle, John Hanson: Life in Utah, or, The mysteries and crimes of Mormonism: being an exposé of the secret rites and ceremonies of the Latter-Day Saints, with a full and authentic history of polygamy and the Mormon sect from its origin to the present time . Ed .: National Publishing Company; Making of America Project. 1870, p. 496–497 (English, archive.org [accessed July 27, 2020]). , described the oath prior to 1970 as a "private, immediate duty to avenge the death of the prophet and martyr Joseph Smith"; George Q. Cannon (Daily Journal of Abraham H. Cannon, December 6, 1889, p. 205). In 1904, several witnesses said that the oath at the time was that the participants would never cease to pray that God would avenge the blood of the prophets on this nation, "and that they would continue this practice to their posterity" through the 3rd and 5th 4th Generation would teach. "David John Buerger: The Mysteries of Godliness: A History of Mormon Temple Worship . Ed .: Smith Research Associates. 2002, ISBN 978-1-56085-176-9 , pp. 134 (English). The oath was removed from the ceremony in the early 20th century.

- ↑ In Heber C. Kimball's diary of December 21, 1845, he says that he "made a covenant in the temple and will never rest ... until those men who killed Joseph and Hyrum are wiped out from the earth." George Q. Cannon (Daily Journal of Abraham H. Cannon, Dec. 6, 1889, p. 205) said he understood that his foundation in Nauvoo included "an oath against the murder of the Prophet Joseph and other prophets," and if he had ever met any of those involved in this massacre, he would undoubtedly have tried to avenge the blood of the martyrs ”.

- ↑ D. Michael Quinn: The Mormon hierarchy: extensions of power . Ed .: Salt Lake City: Signature Books in association with Smith Research Associates. 1997, ISBN 1-56085-060-4 , Diary of Daniel Davis, July 8, 1849, pp. 247 (English).

- ↑ (A Mormon, listening to a sermon given by Young in 1849, noted that Young said, "To shoot someone caught stealing on the spot should not be harmed"); (Another statement said that it would be warranted for a man to thrust a spear through a polygamous woman caught in adultery, but anyone “trying to carry out the sentence ... must have clean hands and a pure heart ... otherwise he'd better let the matter rest ”); Brigham Young: Journal of Discourses . Ed .: Orson Pratt. Volume 3. Liverpool March 6, 1856, Instructions to the Bishops — Men Judged According to their Knowledge — Organization of the Spirit and Body — Thought and Labor to be Blended Together, p. 243–249 ( byu.edu [accessed July 27, 2020]).

- ↑ (“[I] f [your neighbor] needs help, help him; and if he wants salvation and it is necessary to spill his blood on the earth in order that he may be saved, spill it”), (German: Wenn if your neighbor needs help, help him; and if he is to be saved and it is necessary to shed his blood on earth in order to be saved, shed it ) Brigham Young: Journal of Discourses, To Know God is Eternal Life —God the Father of Our Spirits and Bodies — Things Created Spiritually First — Atonement by the Shedding of Blood . Ed .: S. W. Richard. February 8, 1857, p. 215–221 (English, archive.org [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ↑ (“To diverge a little, in regard to those who have persecuted this people and driven them to the mountains, I intend to meet them on their own grounds… I will tell you how it could be done, we could take the same law they have taken, viz., mobocracy, and if any miserable scoundrels come here, cut their throats. (All the people said, Amen. ”); (German: To diverge a little in relation to those who persecuted this people and drove them into the mountains, I intend to meet them on their own land ... I will tell you how it could be done, we could take the same law they took, which is mobocracy, and if any wretched villains come here we will cut their throats (everyone said, amen ) Brigham Young: The Kingdom of God . Ed .: F. D. & S. W. Richards (= Vol. 02 Journal of Discourses ). July 8, 1855, p. 309–317 ( byu.edu [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ↑ Quinn (1997), p. 260 Quotation: German: The LDS leaders publicly and privately encouraged the Mormons to view it as their right, antagonistic outsiders, common criminals, LDS apostates and even loyal Mormons who have committed sins who are worthy of death to kill.

- ^ Letter from Mary L. Campbell to Andrew Jenson, Jan. 24, 1892, LDS archives, in Moorman & Sessions, Camp Floyd and the Mormons , 142.

- ↑ In The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), a patriarchal blessing (also called an evangelist blessing) is a blessing or ordinance given by a patriarch (evangelist) to a church member.

- ↑ Patriarchal blessing of William H. Dame, February 20, 1854, in Harold W. Pease, "The Life and Works of William Horne Dame," M.A. thesis, BYU, 1971, pp. 64-66.

- ↑ Patriarchal blessing of Philip Klingensmith, Anna Jean Backus, Mountain Meadows Witness: The Life and Times of Bishop Philip Klingensmith (Spokane: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1995), pp. 118 & 124

- ↑ Malinda Cameron Scott: Malinda (Cameron) Scott Thurston Deposition . Ed .: Mountain Meadows Association. 1877 (English, mtn-meadows-assoc.com [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ↑ It is uncertain whether the Missouri Wildcats stayed with the slow-moving Baker Fancher group after leaving Salt Lake City. (See Brooks 1991, p. XXI Bagley (2002), p. 280 (Reference “Missouri Wildcats” “Utah mythology”)).

- ^ Mountain Meadows Massacre, John D. Lee. In: mormonismi.net (Finnish, English) (accessed July 28, 2020)

- ^ The West, episode 4 (1856-1868), Deaths Runs Riots. In: pbs.org ( accessed July 28, 2020)

- ↑ Legacy: A Distorted View of Mormon History, Salt Lake City, May 1995, Messenger # 88. In: utlm.org ( accessed July 28, 2020)

- ↑ The Mountain Meadows Massacre: An Aberration of Mormon Practice, by Chris Williams, 1993. In: youknow.com (accessed July 28, 2020)

- ↑ Young (1875)

- ↑ Thomas B. H. Stenhouse: The Rocky Mountain Saints: a Full and Complete History of the Mormons, from the First Vision of Joseph Smith to the Last Courtship of Brigham Young . Ed .: D. Appleton and Company. 1873, LCCN 16-024014 , p. 431 (English, google.de [accessed on July 28, 2020] citing “Argus”, an anonymous employee of the Corinne Daily Reporter , whom Stenhouse met and for whom he vouched).

- ^ Edward Leo Lyman: The Overland Journey from Utah to California: Wagon Travel from the City of Saints to the City of Angels , hardcover. Edition, University of Nevada Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0874175011 , p. 130 (Retrieved February 4, 2019).

- ↑ James H. Martineau: Correspondence: Trip to the Santa Clara . Ed .: Deseret News. volume 9, no. 3 , September 23, 1857, p. 3 (English, utah.edu [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ^ Edward Leo Lyman: The Overland Journey from Utah to California: Wagon Travel from the City of Saints to the City of Angels . Ed .: University of Nevada Press. 2004, ISBN 978-0-87417-501-1 , pp. 133 ( google.de [accessed on July 28, 2020]).

- ↑ Dimick B. Huntington: Huntington Journal . Ed .: LDS Historians Library SLC 1857 (English, mtn-meadows-assoc.com [accessed on July 28, 2020]).

- ^ MacKinnon, p. 57

- ^ Will Bagley, Blood of the prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadow . Ed .: University of Oklahoma Press. Norman 2002, ISBN 978-0-8061-3639-4 , pp. 247 (English, google.de [accessed on July 28, 2020]).

- ^ Brigham Young to Isaac C. Haight, Sep 10, 1857, Letterpress Copybook 3: 827-828, Brigham Young Office Files, LDS Church Archives.

- ↑ MacKinnon, end note 50

- ↑ MacKinnon, p. 17

- ↑ Michael De Groote: Mountain Meadows Massacre affidavit linked to Mark Hofmann. In: Deseret News. September 7, 2010, accessed July 28, 2020 .

- ↑ Keith B. Jeffreys: Mountain Meadows Massacre Artifact Now Believed To Be A Fake . In: Free Inquiry magazine, 22 (4). August 18, 2005, accessed July 27, 2020 .

- ↑ Mountain Meadows affidavit Hofmann forgery? (German: Mountain Meadows affidavit Hofmann's falsification? ), by Christopher Smart, September 10, 2010, Salt Lake Tribune (English) (accessed on July 28, 2020)

- ^ Probable Hofmann Forgery Uncovered (German: Probable Hofmann falsification uncovered ), The Utah Division of State History, (2010), Press Release. In: history.utah.gov ( accessed July 28, 2020)

- ^ Special Report of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, by James H. Carleton, Washington, United States Government Publishing Office, 1902 in the Google Book Search USA

- ↑ James H. Carleton: Special Report of the Mountain Meadows Massacre . Ed .: United States Government Publishing Office. 1902, p. 15 (English, unl.edu [accessed July 29, 2020]).

- ↑ Captain Geo F. Price: Union Vedette. In: Utah Digital Newspapers. June 8, 1864, accessed July 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Captain Geo F. Price: The Mountain Meadows Massacre in Public Discourse. In: Union Vedette, Camp Douglas, Utah. May 25, 1864, accessed July 27, 2020 .

- ↑ American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, September 1857 , by Sally Denton, Vintage Books, New York, 2003, p. 216, ISBN 0-375-72636-5 in the Google Book Search USA

- ^ Scott G. Kenney: History and Faith . Ed .: Signature Books. Volume 9. Salt Lake City 1984 (English, signaturebookslibrary.org [accessed July 29, 2020]).

- ^ Morris A. Shirts: Mountain Meadows Massacre (Utah History Encyclopedia) . Ed .: University of Utah Press. Salt Lake City, Utah 1994, ISBN 978-0-87480-425-6 (English, archive.org [accessed July 29, 2020]): “The most durable was a wall that still stands on the siege site. It was built in 1932 and surrounds the cairn from 1859. ”

- ^ A b Mountain Meadows Association - 1990 Monument. In: mtn-meadows-assoc.com ( accessed July 29, 2020)

- ↑ Utah History To Go, Pioneers and Cowboys, Morris A. Shirts (accessed July 29, 2020)

- ↑ Luscinia Brown-Hovelt & Elizabeth J. Himelfarb: Mountain Meadows Massacre. In: Archaeological Institute of America. November 29, 1999, accessed July 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Mountain Meadows Massacre Monument on Flickr by J. Stephen Conn. In: secure.flickr.com ( accessed July 29, 2020)

- ↑ Jessica Ravitz: LDS Church Apologizes for Mountain Meadows Massacre. In: Salt Lake Tribune. September 11, 2007, accessed July 29, 2020 .

- ^ Peggy Fletcher Stack: Mountain Meadows now a national historic landmark. In: Salt Lake Tribune. July 5, 2011, accessed July 29, 2020 : “Descendants of the Mountain Meadows Massacre of 1857 are calling the Utah National Historic Landmark designation a“ dream of a lifetime, ”thanks to the groups' extraordinary alliance with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. "

- ↑ Nichole Osinski: Archaeologist: Mountain Meadows Massacre graves found. In: The (St. George, Utah) Spectrum. September 20, 2015, accessed on July 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Nichole Osinski: Voices of the Mountain Meadows descendants. In: The Spectrum. November 14, 2015, accessed on July 29, 2020 .

- ^ The Children that died in the Mountain Meadows Mssacre. In: mtn-meadows-assoc.com ( accessed July 30, 2020)

- ↑ a b The Known Victims of the 1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre… In: mtn-meadows-assoc.com (accessed July 30, 2020)

- ↑ Elizabeth Ingram Fancher. In: Find A Grave (accessed August 1, 2020)

- ↑ The following children survived and were returned to their families in northwest Arkansas in September, 1859. In: mtn-meadows-assoc.com (accessed August 1, 2020)

Coordinates: 37 ° 28 ′ 32 " N , 113 ° 38 ′ 37" W.