Oregon Boundary Dispute

The Oregon Boundary Dispute (dt. About "Oregon border dispute") or Oregon Question (dt. About "Oregon question") was a controversy over the political division of the Pacific Northwest of North America between several nations, each of which had territorial claims on the region posed.

Expansion in the region began in the 18th century between the Russian Empire , the United Kingdom , Spain, and the United States . By the 1820s, both the Russians with the Russo-American Treaties of 1824 and the Russo-British Treaties of 1825, and the Spaniards with the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, had formally withdrawn their territorial claims in the region. Through these treaties, the British and US Americans obtained territorial claims in the disputed area. The remaining part of the North American Pacific coast, which was disputed, can be delineated as follows: west of thecontinental divide , north of Upper California from the 42nd parallel north and south of Russian America from 54 ° 40 ′ north latitude; Usually this region was called Columbia District by the British and Oregon Country by the Americans . The Oregon border dispute became significant in geopolitical diplomacy between the British Empire and the Young American Republic, particularly after the British-American War of 1812 .

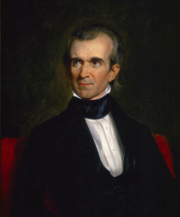

In the presidential election in the United States in 1844 , the Oregon question was to be resolved by annexing the entire area, which corresponded to the position of the Democratic Party . Some researchers have pointed to the United States Whig Party's lack of interest in what they justified with its relative insignificance to other internal problems. The Democratic candidate James K. Polk invoked the Destiny Manifesto and appealed to the expansionist mood; he defeated the Whig Party candidate, Henry Clay . Polk conveyed the previously offered division along the 49th parallel to the British government. Subsequent negotiations stalled when the British plenipotentiaries were still fighting for a border along the Columbia River . Tensions mounted when US expansionists such as Senator Edward A. Hannegan of Indiana and the deputy Leonard Henly Sims from Missouri urged Polk to annex the entire Pacific Northwest to 54 ° 40 'north latitude, as it called for the Democrats during the election had. The uproar gave rise to political slogans such as "Fifty-four Forty or Fight!" As relations with Mexico deteriorated rapidly in the wake of the annexation of Texas , the expansionist agenda of Polk and the Democrats created the possibility of a two-front war for the United States. Just before the outbreak of the Mexican-American War , Polk returned to his previous position of a border along the 49th parallel.

The Oregon Compromise of 1846 established the border between British North America and the United States along the 49th parallel to the Strait of Georgia , where the maritime border swung south to exclude Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands from United States territory. In effect, a small portion of the Tsawwassen Peninsula , Point Roberts , became an exclave of the United States. Vague formulations in the treaty raised doubts about the ownership of the San Juan Islands , as the division “through the middle of the said channel” took place up to the Juan de Fuca Strait . During the so-called Pig Conflict (1859), both nations agreed to a joint military occupation of the island. The German Kaiser Wilhelm I was chosen as a mediator to end the dispute. This set up a three-person commission that decided the conflict in 1872 in favor of the United States. Haro Street thus became the border; the British had preferred Rosario Street . The border between the United States and Canada in the Pacific Northwest was established by the Oregon Compromise and finalized by the arbitration in 1872.

background

The Oregon Question arose in the 18th century during the early exploration of the Pacific Northwest by Europeans and Americans. Several empires (Great Britain, Spain, Russia, and the United States) considered the area suitable for colonization. Seafarers such as the Spaniard Juan José Pérez Hernández , the British George Vancouver, and the American Robert Gray gave some regional waters such as the Columbia River and Puget Sound their modern names and mapped them in the 1790s. Land explorations were initiated in 1792 by the British Alexander Mackenzie ; later the American Lewis and Clark Expedition followed , which reached the mouth of the Columbia in 1805. These explorers often claimed the areas of the northwest coast on behalf of their rulers. The knowledge of the numerous occurrences of fur animals such as the California sea lion , Canadian beaver and the northern fur seal were used to build up an economic network, the Maritime Fur Trade. The fur trade in North America was to remain the main economic interest of Euro-Americans in the Pacific Northwest for decades. The traders along the coast exchanged goods for furs with indigenous peoples such as the Chinook , the Aleutians and the Nuu-chah-nulth .

Spanish colonization

A number of Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest were sent between 1774 and 1794 to establish Spain's claims to the region:

- 1774 - Juan José Pérez Hernández

- 1775 - Bruno de Heceta and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra

- 1779 - Ignacio de Arteaga y Bazán and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra

- 1788 - Esteban José Martínez and Gonzalo López de Haro

- 1789 - José María Narváez

- 1790 - Francisco de Eliza

- 1790 - Salvador Fidalgo

- 1790 - Manuel Quimper

- 1791 - Francisco de Eliza

- 1789-1994 - Alessandro Malaspina di Mulazzo and José de Bustamante y Guerra

- 1792 - Dionisio Alcalá Galiano and Cayetano Valdés

- 1792 - Jacinto Caamaño

- 1793 - Francisco de Eliza and Juan Martínez y Zayas

The colony of Santa Cruz de Nuca was founded on Vancouver Island , making the Spanish the first white colonists in the Pacific Northwest outside of the Russian possessions in the north. A period of tension with the United Kingdom, known as the " Nootka Crisis ", began after the Spanish attacked a British ship. However, three so-called "Nootka Agreements" settled the conflict in that both countries agreed to grant each other access to the Yuquot and to defend this against third parties . Although the Spanish colony was abandoned, there was no consideration in the form of a new boundary in the northern areas of New Spain . Notwithstanding the Nootka Accords, the Spaniards were still allowed to establish colonies in the region, but the lack of any attempt on geopolitical and domestic matters distracted the attention of those in power. With the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, the Spaniards formally gave up their claims to land ownership north of the 42nd parallel.

Russian interests

The government and administration of the Russian Empire founded the Russian-American Company in the ukase of 1799 , a monopoly of Russian fur traders in Russian America. Partly because of the growing Russian activity in the north, the Spaniards created the missions in California to establish colonies in Upper California. Plans to create a Russian colonies in the areas of today's US states Washington and Oregon were of Nikolai Rezanov formulated. He aimed to move the primary colony, Russian America, to the mouth of the Columbia River, although he was unable to reach the river in 1806; the plan was abandoned. In 1808 Alexander Andrejewitsch Baranow dispatched the Russian schooner Nikolai , whose captain "[had] the order to explore the coast south of Vancouver Island, to carry out barter deals with the natives to obtain sea otter pelts and, if possible, the place for a permanent Russian settlement in the Make out Oregon Country ”. The ship failed on the Olympic Peninsula and the survivors did not return to Novo-Arkhangelsk for two years . The ship's failure to find a suitable location led the Russians to believe that large parts of the northwest coast were not worth colonizing. Her interest in Puget Sound and the Columbia River turned to Upper California, where Fort Ross was soon established. The Russian-American Treaty of 1824 and the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1825) with the British formally created the southern border of Russian America at latitude 54 ° 40 ′ north.

Early British-American competition

Neither Russia nor Spain had any substantial plans to establish colonies along the northwest coast in the 1810s. The British and the Americans were the two remaining nations with citizens pursuing economic activities in the region. Starting with a group from the Montreal- based North West Company (NWC) led by David Thompson in 1807 , the British began land-based explorations and opened trading posts throughout the region. Thompson intensively explored the Columbia River basin. At the confluence of the Columbia and Snake Rivers , he erected a stake on July 9, 1811 with the words "Know that this land is claimed by Great Britain as part of its territory ..."; he also stated the intention of the NWC to build a trading post at this point. Fort Nez Percés was founded on this site in 1818. The American Pacific Fur Company (PFC) began operations in 1811 in Fort Astoria , which was built at the mouth of the Columbia River. The outbreak of the British-American War in 1812 did not result in a violent confrontation between competing societies in the Pacific Northwest. Led by Donald Mackenzie , the PFC officials agreed in a contract signed on November 23, 1813, the assignment of their profits to the NWC's competitors. The HMS Racoon , an 18-cannon sloop of the Royal Navy , was ordered to take Fort Astoria, although the post was meanwhile already under the control of the NWC. After the PFC collapsed, American Mountain Men operated in small groups in the region; they were usually stationed east of the Rocky Mountains and met once a year for a rendezvous .

Joint possession

Treaty of 1818

Diplomats from the two states sought negotiations in 1818 to draw the boundaries between the claimed areas. The Americans proposed the division along the 49th parallel, which also east of the Rocky Mountains was the border between the United States and British North America. The lack of precise cartographic knowledge made the US diplomats declare that the Louisiana Purchase would give them incontestable ownership of the region. British diplomats wanted a border further south on the Columbia River to give the North West Company (later the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC)) control of the lucrative fur trade along the river. The diplomatic delegations could not agree on mutually satisfactory formulations and remained in a mutual blockade until October. Albert Gallatin , the Americans' chief negotiator, had previously been instructed to table a provisional agreement by the time the third session of the 15th Congress , scheduled for November 16, was held.

A final offer was made to the British Plenipotentiary, Frederick John Robinson , for the western continuation of the border at the 49th parallel when he left the United Kingdom and, as Gallatin said, "all waters draining into what is known as the Gulf of Georgia" wanted to be attributed to the United Kingdom. This would have included "all the territory west of the Cascade Range and north of the Columbia River watershed to the Gulf" such as all of Puget Sound along with the Strait of Georgia and the Strait of Juan de Fuca in Great Britain. Robinson objected to the proposal. However, the Anglo-American Agreement of 1818, which regulated most of the other conflicts arising from the British-American War of 1812, provided for the joint occupation of the region for ten years.

Division plans

As the expiry of the joint occupation treaty drew near, a second round of negotiations took place in 1824. The US Minister Richard Rush offered to expire the agreement with an additional clause on April 2nd. The 51st parallel was supposed to form a provisional border in the Pacific Northwest, south of which no further British settlements were to be established, nor any American ones north of it. Despite Rush's offer to move the temporary border to the 49th parallel, the offer was rejected by the British negotiators. His proposal was seen as a possible final settlement for the division of the Pacific Northwest. The British Plenipotentiaries William Huskisson and Stratford Canning rushed instead on June 29 with a permanent border along the 49th parallel to the mainstream of the Columbia River. With the British claims to the south and east of the Columbia River formally dropped, the Oregon question focused on what would later become West Washington and the southern part of Vancouver Island. Rush responded to the British proposal and dismissed it as unfavorable, as the British had done with his proposal; he left the conversation and brought it to a standstill.

Throughout 1825, British Foreign Secretary George Canning discussed a potential deal with the United States with HBC Governor John Pelly. Pelly believed the Snake and Columbia Rivers border was beneficial to the UK and his company. When he contacted the US Secretary of State Rufus King in April 1826 , Canning was awaiting an agreement on the Oregon question. Gallatin was the acting United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom and received instructions from Secretary of State Henry Clay in July 1826 to offer the British the division of the Pacific Northwest along the 49th parallel. In an 1826 letter to Prime Minister Lord Liverpool , Canning presented the possibilities of trade with the Qing Empire if an agreement with the Annotations were reached on the partition of the Pacific Northwest. He recognized the American rights to ownership of Astoria, regardless of the fact that continued use by the NWC and later by the HBC was "absolutely unacceptable". Canning saw this diplomatic concession as a weakening of the territorial claims of Great Britain. A border along the Columbia River would result in "immense direct traffic between China and possibly, if we do not divulge it, the limitless foundations on the northwest coast of America."

Resurgence

Huskisson was hired to negotiate with Gallatin along with Henry Unwin Addington. Unlike his predecessor Canning, Huskisson had a negative view of HBC's monopoly and saw the region in an ongoing dispute with the Americans "with little consequence for the British". At the time, HBC employees were the only permanent white settlers in the area, but their economic activities were not used by Huskinisson in exchange with Gallatin. The division offered by Pelly and Canning in 1824 with a border on the Columbia River was rejected. The argument used to respond to the offer was the same as in 1824, that such a border would deny the United States an easily accessible deep-water port on the Pacific . To mitigate this, the British negotiators offered the Americans a detached Olympic Peninsula as American territory with access to the Juan de Fuca Strait and Puget Sound. However, this was unsatisfactory in the eyes of the Americans. Diplomatic talks continued, but a mutually satisfactory solution was not found. The contract of 1818 was renewed on August 7, 1827 with a clause added by Gallatin that a one-year period was introduced if one of the partners wanted to terminate the agreement. After Canning's death and the failure of a satisfactory division of the region with the Americans, "Oregon was almost forgotten by the [British] politicians ...".

Importance in the United States

Regional activities

American Protestant missionaries first came to the area in the 1830s, establishing the Oregon Methodist Mission in the Willamette Valley and the Whitman Mission east of the Cascades . Ewing Young created a sawmill and mill in the Willamette Valley in the early 1830s . He and several other American colonists founded the Willamette Cattle Company in 1837 to bring over 600 head of cattle to the Willamette Valley, with about half of his stake being bought by McLoughlin. More than 700 settlers reached the region in the " Great Migration of 1843 " on the Oregon Trail. The Oregon Country Provisional Government was also established in the Willamette Valley in 1843. Their influence was limited to the interested Americans and the Franco-Canadian employees of the HBC in the valley.

John Floyd

The US government's first proactive efforts to colonize the Pacific Northwest began in 1820 during the 2nd session of the 16th Congress . John Floyd , an MP from Virginia , presided over an initiative that would "authorize the occupation of the Columbia River and regulate trade and relations with the Indians living there." The bill also called for commercial ties to be cultivated with the Chinese Empire and the Tokugawa shogunate . His interest in the far-flung region may have been sparked after meeting former PFC employee Russell Farnham. Floyd had the support of fellow Virginia MP Thomas Van Swearingen and MP Thomas Metcalfe from Kentucky . The bill was presented to both Congress and President Monroe . In Congress, Floyd's bill was defended by a member who said it was not “an attempt at colonial settlement. The territory proposed for occupation is already part of the United States. ”Monroe explored Secretary of State John Quincy Adams' stance on potential corrections. Adams reported: “The paper was flawed from A to Z and full of unsuccessful justifications, individual reflections and rude abuse. Nothing could be corrected except through the fire. ”Treated twice before the end of the legislature,“ very few MPs considered this to be a serious procedure ”; it was refused.

Floyd went on to legislate for a U.S. Pacific colony. His MP career ended in 1829, but the Oregon issue was not brought up again in Congress until 1837. The northern limit proposed by Floyd was initially 53 degrees, later 54 ° 40 ′ north. These bills continued to meet the disinterest or opposition of other members of Congress. One in particular was voted 100 to 61. Missouri Senator Thomas H. Benton became a supporter of Floyd's endeavors and considered “sowing the seeds of a powerful and independent power beyond the Rockies.” John C. Calhoun , then Secretary of War and at the same time interested in Floyd's bills, gave expressed his opinion that the HBC was an economic threat to the commercial interests of the United States in the West.

"... as long as British fur traders have free access to the Rocky Mountains region from various outposts ... they will monopolize the fur trade west of the Mississippi on a large scale in order to completely displace our own trade in the next few years.

Presidential election 1844

The 1844 presidential election in the United States was definitely the turning point for the United States. The admission of the Republic of Texas into the confederation through diplomatic negotiations at the beginning of the process of the annexation of Texas was controversial. At the same time, the Oregon question became "a weapon in the struggle for internal power." At the 1844 National Democratic Convention, the party manifesto declared “That our claim to all of Oregon Territory is clear and unequivocal; that no part of it should be ceded to England or any other power, and that the reconquest of Oregon and the re-annexation of Texas at the earliest possible time are great American measures… ”Linking the Oregon dispute to the more controversial debate over Texas the Democrats appealed to expansionist members from both the Northern and Southern states. The expansion in the Pacific Northwest offered the opportunity to allay fears in the north of adding Texas to another slave state by adding more free states as a balance in return. Democratic candidate James K. Polk came out on top of a narrow victory over United States Whig Party candidate Henry Clay , in part because Clay took a stand against immediate expansion in Texas. Despite the use of the Oregon question in the election, according to Edward Miles, the point was "not an important part of the campaign" because "the Whigs would have continued the discussion."

"Fifty-four Forty or Fight!"

A popular slogan that was later linked to Polk and his 1844 election campaign, "Fifty-four Forty or Fight!", Was actually not during of choice. It appeared only until January 1846, partly advertised and driven by the press affiliated with the Democratic Party. The phrase has since been mistakenly identified as Polk's campaign boxes, even in some books. Bartlett's Familiar Quotations , a popular book of quotations, attributes the slogan to William Allen a . 54 ° 40 ′ north was the southern border of Russian America and was considered the northernmost border of the Pacific Northwest. An actual Democratic campaign slogan used for this election (in Pennsylvania ) was the rather mundane "Polk, Dallas , and Duty Cycle of '42".

British interests

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) merged with the North West Company in 1821 and took over many of their fur trading stations. The HBC was licensed as British to trade with the numerous indigenous peoples of the region. Their networks and trading posts stretched south from New Caledonia , another HBC fur trading district, to the Columbia Basin (most of New Caledonia is south of 54 ° 40 'N). HBC's headquarters for the entire region was established in Fort Vancouver (modern Vancouver (Washington) ) in 1824 . Later that year, George Simpson discussed the "uncertain claims on Columbia" with Governor Colville ; he considered ending activities on the river. "If the Americans settled at the Columbia Estuary, I think it would be necessary to leave the coast [south of the river] ..." stated Simpson; the posts of the HBC should be "moved to the north ...". At its peak in the late 1830s / early 1840s, Fort Vancouver oversaw 34 outposts, 24 ports, six ships and 600 employees.

Domestic view

The Edinburgh Review declared the Pacific Northwest to be "the last corner of the earth free from occupation by a civilized turf." If Oregon were to be colonized, the map of the world could be considered filled ”.

Navy presence

The ships of the Royal Navy were ordered to the Pacific Northwest during these decades to both expand the cartographic knowledge and protect the fur trading stations. The British stationed the Pacific Station in Valparaíso in Chile in 1826 , thereby increasing the navy's strategic capacities. A squadron was moved there. Ships were later dispatched to the Pacific Northwest and stationed outside the port. The HMS Blossom stayed in the region in 1818. The next exploration expedition was carried out in 1837 with the HMS Sulfur and the HMS Starling ; activities continued until 1839. In July 1844, the HMS Modeste reached the Columbia River from Pacific Station to get clarification about the HBC stations. Chief clerk James Douglas complained that "Navy officers have more taste for a lark than a 'musty' lesson on politics or the larger relevant issues of national concern." The Modeste visited the HBC trading posts in forts George, Vancouver, Victoria and Simpson .

Political Efforts During Tyler's Presidency

Lewis Linn , a Senator from Missouri, introduced legislation in 1842, inspired in part by Floyd's previous efforts. Linn's proposal required the government to make land grants to men interested in colonizing the Pacific Northwest. The arrival of Alexander Baring, 1st Baron Ashburton , in April 1842, dispatched to resolve several territorial disputes with the United States, delayed Linn's legislative process. Originally focused on the Pacific Northwest, Ashburton presented Canning's 1824 proposal to Secretary of State Daniel Webster to divide it along the Columbia River. Webster rejected the offer for the same reasons that it had previously been rejected; partition would leave the United States with no suitable locations for a large Pacific port. Webster pointed out that Ashburton's proposal could be acceptable to the Americans if they were compensated with Mexico's San Francisco Bay . Ashburton forwarded the offer to his superiors, but no further action was taken. Both diplomats focused on the Aroostook War and formulated the Webster-Ashburton Treaty .

At the final session of the 27th Congress on December 19, 1842, Linn presented a similar bill for the colonization of the Pacific Northwest, which he formulated "by the Anglo-American race, which will extend our borders from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean". The debate on this draft lasted more than a month; it was finally accepted in the Senate with 24 votes to 22. In opposition to Linn's bill, the Calhoun statement came out that the US government should pursue a policy of "wise and masterful inactivity" b in Oregon so that settlement would determine the final boundary. However, many of Calhoun's Democratic Party comrades soon began to advocate a more direct approach.

By early 1843, Webster returned to the Oregon Question and formulated a plan that included the British offer of 1826 for the enclave on the Olympic Peninsula and the purchase of Upper California from Mexico. The increasing hostility between President Tyler and the Whig Party led to Webster's disinterest in continuing as Secretary of State and his plan was postponed. The US Secretary of State for the United Kingdom, Edward Everett , was given authority in October 1843 to resolve the Oregon question with British officials. In a meeting with Prime Minister Robert Peel's Secretary of State George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen , on November 29, Everett presented the wording examined by President John Tyler . The old offer from the 49th parallel along with free access to the Columbia River was presented once again. In President Tyler's State of the Union address on December 6th of that year, however, he claimed "the entire region of the country on the Pacific Ocean between 42 ° and 54 ° 40 'north latitude". Upon receiving this declaration, Aberdeen began to consult the committee and Governor Pelly, who had previously been excluded from most diplomatic negotiations.

Polk Presidency

In his inauguration speech in March 1845, President Polk said, quoting the party program, that the United States' claims to Oregon were "clear and unquestionable." Tensions grew, with both sides stepping up border security efforts in the face of a possible war. Despite Polk's brazen language, he was willing to compromise and wasn't really afraid of a war over Oregon. He believed that a firm stance would force the British to agree to a resolution acceptable to the United States. During a meeting with Rep. James A. Black on January 4, 1846, Polk said, “The only way to treat John Bull [is] to look him straight in the eyes ... if Congress hesitates [sic] ... would John Bull instantly became arrogant and more covetous in his demands… ”But Polk's position on Oregon was not just posture: he genuinely believed that the United States had a legitimate claim to the entire region. He rejected British offers to settle the dispute through arbitration for fear that no independent third party could be found.

Many newspaper publishers in the United States raged with Polk claiming the entire region, as the Democrats suggested in their 1844 election campaign. Headings such as "All Oregon or Nothing" by the editor of the Union Thomas Ritchie appeared on November 6, 1845. In a column in the New York Morning News on December 27, 1845, editor John L. O'Sullivan advocated that the United States should claim all of Oregon "by the right Providence gave us, our obvious destiny to spread across the continent and take possession of it ...". Soon afterwards, the term “ obvious purpose ” became a standard formulation of the expansionists and an integral part of US parlance. O'Sullivan's version of the "obvious destination" was not a call to war, but such calls soon surfaced.

After Polk's inauguration, British diplomats received instructions influenced by HBC leaders such as Simpson, whose proposals were forwarded to British Ambassador to the United States Richard Pakenham via Pelly and then via Aberdeen. In a letter to Calhoun dated August 1844, Pakenham advocated a border along the Columbia River. He offered the option - probably from Simpson: the Americans could choose naval bases in return on the part of Vancouver Island south of the 49th parallel or along the Juan de Fuca Strait. Diplomatic channels continued negotiations through 1844; By early 1845, Everett reported Aberdeen's willingness to accept the 49th parallel, provided the southern part of Vancouver Island became British territory.

In the summer of 1845, the Polk Administration renewed its proposal to divide Oregon along the 49th parallel to the Pacific. US Secretary of State James Buchanan offered the British several designated ports on the southern part of Vancouver Island on July 12, but the navigation rights on the Columbia River were not included. Because this proposal fell short of the previous offer by the Tyler administration, Pakenham rejected it without first contacting London. Offended, Polk officially withdrew the proposal on August 30, 1845 and broke off negotiations. Aberdeen punished Pakenham for this diplomatic misstep and ordered the dialogue to be restarted. By then, however, Polk had become suspicious of British intentions and, under increasing political pressure, he was unwilling to compromise. He refused to restart the negotiations.

Threats of war

| Significant People on the Oregon Question | |

|---|---|

| United States | United Kingdom |

|

James K. Polk President |

Robert Peel Prime Minister |

|

James Buchanan Secretary of State |

Earl of Aberdeen Foreign Secretary |

|

Louis McLane Ambassador to the United Kingdom |

Richard Pakenham Ambassador to the United States |

Pressure from Congress

In his inaugural address to Congress on December 2, 1845, Polk recommended that the British be given the required one year period after which the agreed joint occupation of Oregon should end. Midwestern Democratic expansionists in Congress , led by Senators Lewis Cass of Michigan , Edward A. Hannegan of Indiana, and William Allen of Ohio , called for war against the United Kingdom rather than any claim south of 54 ° 40 ′ north to waive. These statements were fueled by a number of factors, including traditional Anglophobia and a belief in "better" claims and "better" use of the land by Americans.

The debate was not conducted strictly along party lines. Many who shouted for a border at 54 ° 40 ′ north brought the Northerners against Polk's will to compromise across the border in the Pacific Northwest. Polk's uncompromising pursuit of Texas, a beneficial acquisition for Southern slave owners, enraged many proponents of "54-40" as Polk himself was a southerner and slave owner. As historian David M. Pletcher noted, "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight" seemed more addressed to the Southern aristocracy than to the United Kingdom.

Moderate officials like Webster warned that the United States could not win a war against the British Empire ; Negotiations could still achieve US territorial goals. Webster confided on February 26, 1846 to his personal friend Viscount Ossington that it would be "a total foolishness and a great crime" for the two nations to wage war over the dispute over the Pacific Northwest.

British response

Naval Forces in the Pacific

At the height of tensions with the United States in 1845 and 1846, there were at least five British Navy ships operating in the Pacific Northwest. The ship of the line HMS Collingwood , equipped with 80 cannons, was moved to Valparaíso in 1845 under CinC Rear Admiral Sir George Francis Seymour with orders to report on the situation in the region. The HMS America, under the command of Captain John Gordon (the younger brother of the Foreign Secretary Aberdeen), was therefore sent north in the same year. HBC chief executive Roderick Finlayson led the naval officers on a tour of Vancouver Island, where Gordon expressed his negative assessment of the Northwest region. During a deer hunt on the island, Gordon informed Finlayson that he "would not give one of the bare rocks of Scotland for everything he saw around him." The America departed from the Strait of Juan de Fuca on October 1, 1845th The Modeste reached the Columbia River and Fort Vancouver on November 30, 1845, where it remained until May 4, 1847. The American colonists in the Willamette Valley did not consider the modest to be beneficial, they felt threatened by the large warship. Relations improved after the officers organized a ball in Vancouver on February 3, 1846 ; later there were theatrical performances by the ship's crew, including Love in a Village , an opera by Thomas Arne , and The Mock Doctor , a play by Henry Fielding , as well as some picnics .

The HMS Fisgard was the first reinforcement ordered to the region by Rear Admiral Seymour's Pacific Station in January 1846. Captain Duntze should "provide support to Her Majesty's subjects in Oregon and on the Northwest Coast ..." and avoid any potential confrontation with US settlers. On May 5th, the Fisgard reached Fort Victoria. She was transferred to Fort Nisqually on the 18th , where she remained until October. To assist other British ships and navigate complicated canals and rivers, the paddle steamer HMS Cormorant reached the Juan de Fuca Strait in June. Two scout ships were relocated from Plymouth in June 1845 , the HMS Herald and the HMS Pandora , to map the coast of America. The ships reached Cape Flattery on June 24, 1846. The Cormorant took the Herald in tow to Fort Victoria three days later. The Herald and Pandora spent several months mapping Puget Sound and Vancouver Island through September 2. That day they left for Upper California. The Fisgard and the Cormorant left for Valparaíso in October. After the Modeste was the only British ship to remain in the region in 1847, "[the Oregon Compromise] seemed to have taken the edge off the Royal Navy's interest in the Northwest Coast."

War plan

Because of his extensive travels through all the stations of the HBC, Governor Pelly instructed George Simpson to draw up a plan for the British government according to which hostilities with the Americans could arise. The proposal was finalized on March 29, 1845, and Simpson identified two areas in which offensives could be launched. The Red River Colony would be the base of operations for forays into the Great Plains , an expansive region that was then sparsely populated by Americans. A militia made up of Métis fighters and neighboring First Nations such as the Anishinabe was to be formed together with an infantry garrison from the British Army . To secure the Pacific Northwest and the Columbia River, Simpson thought Cape Disappointment was of critical importance. A naval formation of two steamers and two ships of the line was supposed to bring a unit of the Royal Marines there to set up a coastal battery . The recruitment, Simpson hoped, would bring a force of 2,000 Northwest Coast Métis and Indians led by officers of the regular army to the region. His proposal quickly met the interest of the British government when he met Prime Minister Peel and Foreign Secretary Aberdeen on April 2nd. A thousand pounds sterling was suspended to lay the foundation for defensive operations in the Pacific Northwest. The war and colony Minister Lord Stanley favored the plan and explained that the HBC military operations west of Sault Ste. Marie have to finance.

The solution

Aberdeen had little intention of heading for a war because of a region that was of minor economic importance for the United Kingdom. Rather, the United States was an important trading partner, particularly in the need for American wheat for use during the Great Famine in Ireland . Aberdeen and Pakenham negotiated from a position of strength. The key was the overwhelming naval power that the British could wield against the United States; Added to this was a diplomatic and political landscape that was ultimately conducive to Britain's goal of robustly protecting its interests without armed conflict. The British politicians and naval officers finally realized that any conflict over the border in Oregon, like the war of 1812 on the east coast of the United States and the Great Lakes , would be unsatisfactorily resolved for them. The presence of the Royal Navy on the Atlantic coast was far less numerical than that of the Americans; so far, general superiority over the US Navy had been critical to US decisions during the crisis, particularly its willingness to compromise. Louis McLane , the US Secretary of State in the United Kingdom, reported to Buchanan on February 2 that the British were prepared to "dispatch around thirty ships of the line immediately and keep steamers and other ships in reserve ...". The word of Polks Bluff had got around.

The American diplomat Edward Everett contacted the leader of the Whigs , John Russell , on 28 December 1845, it supported a revision of the American offer that allowed the British, not to keep Vancouver Iceland. He warned Russell that some influential Whigs might stall the negotiations. "If you choose to rally public opinion in England against this basis of compromise, it would not be easy for Sir R. Peel and Lord Aberdeen to agree to it." Because he still considers the Columbia River important to the British Russell Aberdeen assured his support in solving the Oregon question. While Everett was influential in this political movement, it appeared to Russell, as Frederick Merk pointed out, "prudent Whigs political behavior" to support Aberdeen in this case.

Although Polk had called on Congress in December 1845 to pass the resolution to end the joint occupation with the British, it did not do so until April 23, 1846, when both Houses agreed. Adoption was delayed, especially in the Senate, due to the ongoing debate. Several Southern Senators such as William S. Archer and John M. Berrien were wary of the British Empire's military capabilities. Ultimately, a moderate resolution was passed, the text of which called on both governments to settle the matter amicably.

Despite the great differences, the moderate forces had triumphed over the warmongers. Unlike the Democrats in the West, most congressmen - like Polk - did not want to fight for 54 ° 40 ′. The Polk administration then announced that the British government should provide formulations for an agreement. Notwithstanding the cooled diplomatic relations, the repetition of the British-American War was not popular with either government. Time was of the utmost importance, as it was well known that the Peel government would fall with the impending repeal of the Corn Act in the UK; negotiations would have to start again with a new government. At a time when the balance of power in Europe was a much more pressing problem, a war with a major trading partner of the British government would not have been the case. Aberdeen and McLane quickly worked out a compromise and sent it to the United States.

Oregon Compromise

Pakenham and Buchanan drafted a formal treaty known as the Oregon Compromise, which the Senate ratified on June 18, 1846 by 41 to 14 votes. The limit was set at the 49th parallel, which was the original proposal by the United States; in addition, the British living in the region were granted navigation rights on the Columbia River. Senator William Allen, one of the strongest supporters of the 54-40 claim, felt betrayed by Polk and stepped down from chairing the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee . The signing of the treaty ended the joint occupation of the region and made most of the settlers in Oregon south of the 49th parallel citizens of the United States.

Henry Commager assessed the settlement factors as "a combination of temporary, accidental, and circumstantial phenomena, irrelevant to the local situation, largely outside of American control and alien to American influence." The Canadian Hugh LL. Keenlyside, professor and diplomat, and the American Gerald S. Brown wrote, a century after the conclusion of the contract,

“Given the conditions, [he] was appropriate and fair. Neither nation had an exact legal title to anything in that territory , and the result was de facto equality. Great Britain got the better ports and larger deposits of mineral raw materials, wood and fish; the United States got much more arable land and an area that has an overall better climate. The decision is also almost unique among the American border disputes in that it has been accepted with reasonable satisfaction by both nations. A better proof of justice could hardly be demanded. "

The formulations of the Oregon Compromise were essentially the same as those previously used by the Tyler administration, and thus represented a diplomatic victory for Polk. Polk, however, was often criticized for his actions on the Oregon issue. The historian Sam W. Haynes characterizes Polk's policies as " brinkmanship " (Eng. About "playing with fire"), which "brought the United States dangerously close to a useless and potentially disastrous conflict". David M. Pletcher notes that while Polk's bellicose stance was the by-product of internal American policy, the threat of war was "largely his own creation" and could have been avoided "with more sophisticated diplomacy." According to Jesse Reeves, "if Palmerston had been in Aberdeen's position at the time of Polk's 'robust' offer, Polk could have lost Oregon". Aberdeen's desire for peace and good relations with the United States “is responsible for the settlement that Polk believed he had achieved through resolute policies. That Aberdeen was 'bluffed' by Polk is absurd ”.

The treaty was ambiguous with regard to the demarcation of the boundary that was to follow "the deepest canal" outside the Juan de Fuca Strait and which left the fate of the San Juan Islands in the dark. After the " pig conflict", the arbitration court of the German Emperor Wilhelm I led to the Treaty of Washington in 1871, which awarded the entire islands to the USA.

Politicians and the public in Upper Canada were dissatisfied with the Oregon Compromise as the British once again ignored their interests; they were looking for greater autonomy in international affairs.

Historical maps

The border between the British and US territories was represented differently by contemporaries:

A map of the United States shows the border at 54 ° 40 ′ north near Fort Simpson

A British map from 1844 British shows the Columbia River as a border

A map from 1846 shows the 49th parallel as the border across Vancouver Island

literature

- Donald A Rakestraw: For Honor or Destiny: The Anglo-American Crisis Over the Oregon Territory. Peter Lang, New York 1995, ISBN 978-0-8204-2454-5 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Richard Somerset Mackie: Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793-1843 . University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, BC 1997, pp. 29, 124-126, 140.

- ↑ a b c d E.A. Miles: "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight" —An American Political Legend . In: Mississippi Valley Historical Review . 44, No. 2, 1957, pp. 291-309. doi : 10.2307 / 1887191 .

- ^ Grigory Langsdorff: Langsdorff's Narrative of the Rezanov voyage to Nueva California in 1806 . The Private Press of Thomas C. Russell, San Francisco, CA 1927, p. 21.

- ^ A b Alton S. Donnelly: Kenneth N. Owens (Ed.): The Wreck of the Sv. Nikolai . The Press of the Oregon Historical Society, Portland, OR 1985.

- ^ TC Elliott: David Thompson, Pathfinder and the Columbia River . In: The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society . 12, No. 3, 1911, pp. 195-205.

- ↑ Hiram M. Chittenden: The American Fur Trade in the Far West , Volume 1. Francis P. Harper, New York City 1902.

- ↑ a b c d Frederick Merk: The Ghost River Caledonia in the Oregon Negotiation of 1818 . In: The American Historical Review . 50, No. 3, 1950, pp. 530-551. doi : 10.2307 / 1843497 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o John S. Galbraith: The Hudson's Bay Company as an Imperial Factor, 1821-1869 . University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1957.

- ^ A b William I. Marshall: Acquisition of Oregon and the Long Suppressed Evidence about Marcus Whitman , Volume 1. Lowman & Hanford Co., Seattle 1911.

- ^ A b Edmond S. Meany: Three Diplomats Prominent in the Oregon Question . In: University of Washington (Ed.): The Washington Historical Quarterly . 5, No. 3, 1914, pp. 207-214.

- ^ A b George Canning: Stapleton, Edward J. (Ed.): Some Official Correspondence of George Canning , Volume II. Longmans, Green and Co., London 1887, pp. 71-74.

- ^ A b c d Kenneth E. Shewmaker: Daniel Webster and the Oregon Question . In: Pacific Historical Review . 51, No. 2, 1982, pp. 195-201. doi : 10.2307 / 3638529 .

- ^ Oregon History: Land-based Fur Trade and Exploration . Archived from the original on November 16, 2006. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, Joyce White: Ewing Young Route . Archived from the original on December 10, 2006. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Salem Online History: Salem's Historic Figures . Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ A b Thomas H. Benton : Thirty years' view , Volume 1. D. Appleton and Co., New York 1854, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ a b c d e Joseph R. Wilson: The Oregon Question. II . In: Oregon Historical Society (Ed.): The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society . 1, No. 3, 1900, pp. 213-252.

- ↑ John Quincy Adams : Adams, Charles F. (Ed.): Memoirs of John Quincy Adams , Volume 5. JB Lippincott and Co., Philadelphia 1875, p. 238.

- ^ A b c d Lester B. Shippee: The Federal Relations of Oregon . In: Oregon Historical Society (Ed.): The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society . 19, No. 2, 1918, pp. 89-133.

- ^ A b Norman A. Graebner: Empire on the Pacific; a study in American continental expansion . New York Ronald Press Co., New York 1955.

- ^ Democratic Party Platform of 1844 . Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ A b Eugene H. Rosenboom: A History of Presidential Elections: From George Washington to Richard M. Nixon , 3rd Edition, Macmillan, New York 1970.

- ↑ a b c d e f g David M. Pletcher: The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War . University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO 1973.

- ^ Hans Sperber: "Fifty-four Forty or Fight": Facts and Fictions . In: American Speech . 32, No. 1, 1957, pp. 5-11. doi : 10.2307 / 454081 .

- ↑ a b c Frederick Merk: Fur Trade and Empire; George Simpson's Journal 1824-25 . Belknap, Cambridge, MA 1968.

- ^ A b Frederick Merk: British Party Politics and the Oregon Treaty . In: The American Historical Review . 37, No. 4, 1932, pp. 653-677. doi : 10.2307 / 1843332 .

- ↑ Edinburgh Review: The Edinburgh Review or Critical Journal: For July, 1843 .... October, 1843 , Volume 78.Ballantyne and Hughes, Edinburgh 1843.

- ^ John McLoughlin: Rich, EE (ed.): The Letters of John McLoughlin from Fort Vancouver to the Governor and Committee, Third Series, 1844-1846 1944.

- ^ A b c d F. V. Longstaff, WK Lamb: The Royal Navy on the Northwest Coast, 1813-1850. Part 1 . In: The British Columbia Historical Quarterly . 9, No. 1, 1945, pp. 1-24.

- ^ A b Government Printing Office: Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington , Volume V. Government Printing Office, Washington DC 1872, pp. 6-11.

- ^ 1843 State of the Union Address . Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ↑ Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations. 1989. . Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ↑ James K. Polk: Inaugural Address of James Knox Polk . Yale Law School. 2014. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ↑ James K. Polk: Quaife, Milo M. (Ed.): The Diary of James K. Polk during his Presidency, 1845 to 1849 , Volume 1. AC McClurg & Co., Chicago 1910.

- ↑ a b c d Sam W. Haynes: James K. Polk and the Expansionist Impulse . University of Texas, Arlington 1997.

- ^ Reginald Horsman: Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism . Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 1981.

- ^ Charles M. Wiltse: Daniel Webster and the British Experience . In: Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society . 85, 1973, pp. 58-77.

- ^ A b c d e f g F. V. Longstaff, WK Lamb: The Royal Navy on the Northwest Coast, 1813-1850. Part 2 . In: The British Columbia Historical Quarterly . 9, No. 2, 1945, pp. 113-128.

- ^ Roderick Finlayson: Biography of Roderick Finlayson 1891.

- ^ Ball at Vancouver . In: The Oregon Spectator (Oregon City, OR) February 19, 1846, p. 2. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Theater at Vancouver . In: Oregon Spectator (Oregon City, OR) on May 14, 1846, p. 2. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ A b Berthold Seemann: Narrative of the Voyage of the HMS Herald during the years 1845-51 . Reeve & Co., London 1853.

- ^ Barry M. Gough: The Royal Navy and the Northwest Coast of North America, 1810-1914 . University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, BC 1971, pp. 70-83.

- ^ Miller, Hunter (Ed.): Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States of America , Volume 5. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 1937.

- ^ Cong. Globe, 28th Cong., 1st Sess. 520 (1846)

- ^ Cong. Globe, 28th Cong., 1st Sess. 511 (1846)

- ^ Dale L. Walker: Bear Flag Rising: The Conquest of California, 1846 . Macmillan, New York 1999, ISBN 0312866852 .

- ^ Henry Commager: England and Oregon Treaty of 1846 . In: Oregon Historical Society (Ed.): Oregon Historical Quarterly . 28, No. 1, 1927, pp. 18-38.

- ↑ Alfred A. Knopf: Keenlyside, Hugh LL. & Brown, Gerald S. (Eds.): Canada and the United States: Some Aspects of Their Historical Relations . Alfred A. Knopf, 1952. , OCLC 469525958

- ↑ a b Jesse S. Reeves: American Diplomacy under Tyler and Polk . The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore 1907.

Other sources

- Sir James Douglas, Chapter V The Oregon Boundary , Robert Hamilton Coats and R. Edward Gosnell, publ. Morang, Toronto, 1908

- A history of British Columbia , Chapter IX "The Oregon Boundary", pp 89-96, EOS Scholefield, British Columbia Historical Association, Vancouver, British Columbia, 1913

Web links

Party programs and speeches

- Polk's inauguration speech of March 1845 , in which he asserts the "clear and unquestionable claim"

- Polk's message to Congress of December 1845 calling for an end to the common occupation of Oregon

Political cartoons from Harper's Weekly, 1846

- "Polk's Dream" in which the devil, disguised as Andrew Jackson, instructs Polk to fight for the border at 54 ° 40 ′ north

- "Present Presidential Position" , in which the donkey of the Democrats is at 54 ° 40 ′ north

- "Ultimatum on the Oregon Question," Polk speaks to Queen Victoria while others provide comments

- "War! Or No War!" , Two Irish immigrants quarrel over the border issue

Others

- Fifty-Four Forty or Fight on About.com, an example of a reference incorrectly identifying the phrase as an 1844 campaign slogan

- 54-40 or Fight shows the quilt blocknamed after the slogan. Back then, women often used quilts to express their political views.