Fur trade in North America

The fur trade in North America was one of the first economic uses of the North American continent by Europeans. The beginnings of the business lay in the 16th century, the greatest political importance it reached in the 17th century, the economic climax in the first third of the 19th century. In the rapidly industrialized and urbanized world after the First World War, with a population that grew much faster than the fur animal populations and breeders could supply, the fur trade in North America finally lost its prominent importance after the Second World War. To this day, it only plays a certain role in a regional, rural setting.

Fur hunters and dealers are among the most important discoverers and pioneers of the European settlement of the continent; they were often the first to make contact with Indians and Eskimos .

Associated with the fur trade are names such as the Anglo-Canadian Hudson's Bay Company , the French-Canadian North West Company and the German-born Johann Jacob Astor and his American Fur Company , but also the Russian-American Company and the Alaska Commercial Company .

Research since the 1970s has shown that the term fur trade is too simplistic. It was not simply a preliminary stage of European colonization, as Frederick Jackson Turner in 1891 and especially Harold A. Innis in 1930 postulated. Today it is clear that it was an Indian trade. For Arthur J. Ray (1978) it was only one aspect of the Indian trade. The Indians first integrated the newcomers into their trading system, even if the smallpox that the Europeans brought with them claimed numerous victims. The leadership groups of many tribes depended on the fur trade, or they only established themselves through its income and the prestige that the associated barter goods, especially wampum , earned. As part of the fur trade, new ethnic groups emerged, especially the Métis .

Since the relationships within and between the groups also changed, one spoke of a “fur trade society”, a “fur trade society” which, above all, left its mark on the not yet urbanized Canadian society before the First World War .

The European markets

Fur hunting and trading on the North American continent only served the smallest part of the supply of the own population. Rather, the natural resources of the colonies were developed specifically for the demand on the European markets from the start. Beaver fur in particular was in great demand because it was not subject to any dress codes even in the Middle Ages and so could be worn by the nobility and the bourgeoisie. The greatest demand was for hats made from beaver felt. The under hair, after removing the top hair, was the ideal raw material for matting and manufacturing high quality hats.

From the 17th century, fashion, including hat fashion, emanated from the economic centers of England and France; beaver felt was the preferred material for high-quality hats of almost every style. This fashion started in 1600 and then especially in the Thirty Years War with the rise of Sweden as a European power. During this time, wide-brimmed hats made of felted beaver hair were worn based on the Swedish model. Further demand came in the second half of the 17th century with the standing armies of European nations, whose uniforms included headgear made of beaver felt.

The beginnings

The European beaver populations declined due to the exploitation of stocks and amelioration measures to drain wetlands, around 1600 the stocks of Russia were also exhausted and imports from the east came to an almost complete standstill. The development of the North American continent began around the same time. Furs were the ideal commodity for the economic use of the transatlantic colonies: The extraction hardly required any infrastructure, the furs could be exchanged by the Indians or obtained by European fur hunters themselves, they were easy to transport and fetched good prices.

From 1519 the fur trade began on the coast. The Indians there exchanged furs for European products, especially metal goods such as knives, axes, hatchets and kettles. Their interest in exchanges grew, as the report by Jacques Cartiers , who anchored in Chaleur Bay in 1541, shows. There his ship was surrounded by a large number of Mi'kmaq canoes , their crews waving beaver pelts . Cartier had already exchanged furs with the Iroquois on the upper St. Lorenz in 1534/35 .

However, a link between trade contacts and the spread of the most serious epidemics among the indigenous peoples, especially smallpox, soon emerged, which was not expected by both sides . In 1564, 1570 and 1586 the Mi'kmaq were afflicted by diseases unknown to them. Soon the tribes were also waging wars among themselves because of the trade contacts, especially after the first permanent bases of the traders were established after 1600. In 1607 a war broke out between the Penobscot under their Sagamore Bashabes , who had gained great power through French arms, and the Mi'kmaq. This Tarrantine War , an expression of their rivalry in the fur trade, lasted from 1607 to 1615.

For a long time, trade flourished despite a largely lacking infrastructure in the sense of trading bases. A network of rivers and roads on which Indians traded had existed for a very long time, and the white traders were integrated into this trade network.

Monopolies, European conflicts and fur wars

However, trade was only organized by the state decades later. In 1603, Henry IV of France granted Pierre Dugua de Mons , a nobleman from St. Malo , the royal privilege for fishing and fur trading in all French possessions on the North American continent. He founded a trading company with merchants from Brittany and crossed the Atlantic. The expedition spent the winter of 1604/05 on Saint Croix Island before setting up the first French settlement on the continent in the New Scottish Acadia in 1605 , from which the city of Port Royal (now Annapolis Royal ) developed. Dugua de Mons' companion was Samuel de Champlain , who founded Québec in 1608 and thus made the first step towards colonizing the continent.

A few years later conflicts arose between the French and southern English colonists. In 1613 the English attacked Port Royal and burned the city down. Trade shifted to the north, to little Tadoussac , at the confluence of the Saguenay in the St. Lorenz, where the Indian trade took off. In 1627, Cardinal Richelieu granted the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France (also known as the Compagnie des Cent-Associés ) a new patent for trading in what is now known as Canada . The conflicts and violence remained. In 1632 France and England signed the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye , in which French rights were confirmed.

Conflicts with the Indians led to a dichotomy in trading methods. A few French went into the "wilderness" and lived with the Indians. They were called Coureurs des Bois and are the role models for the rangers in early American adventure literature. They lived out of the country with the locals and met their low needs for European goods by selling self-hunted furs. The official trading agents, on the other hand, set up permanent branches, mostly at the mouth of rivers, and had furs delivered directly to the agency by the local Indians. Metal tools, knives, kettles and pots, as well as colorful textiles and Venetian glass beads served as barter goods . Not only the obvious advantages of the tools played an important role, but also the taste that women, for example, found in certain colors of the often artistic pearls.

On the one hand, this trade was often made more difficult by the rivalries between the English and the French. The English conquered Québec from 1629 to 1632. The third power was the Dutch, who supplied the Iroquois with weapons that they could use to expand their hunting ground further north. This sparked conflicts between the Iroquois and the Hurons, allied with the French, and other tribes, which resulted in the annihilation of the Hurons in 1650, the Erie in 1656, and other tribes. In 1660 the Iroquois attacked the French too.

After direct trade with the Indians had been released in 1652 - until then only Indians could enter the trading centers - France tried to make Montreal the only trade center for furs. However, this was unsustainable for the Iroquois. Their leaders now depended on bartering themselves, because they gained prestige by giving away coveted goods, most of which they received in exchange for furs. The fur monopoly became a threat to them. Therefore, they attacked Montreal in 1687, a total of about one in ten of the nearly 3,000 French died in the war. With the King William War (1689 to 1697) began a chain of proxy wars that England and France fought with the help of their Indian allies. Only at the end of this war, a side war of the Palatine War of Succession , did negotiations come about in 1698 and in 1701 the Great Peace of Montreal between the Iroquois and the French. This ended the last of the so-called Beaver Wars after around 60 years .

Ten years after the destruction of the Hurons, two rangers returned to Trois-Rivières in 1660 , their 60 canoes fully loaded with furs. Médard Chouard, Sieur des Groseilliers and Pierre-Esprit Radisson set off for the Great Lakes with colleagues last year , explored the area and got to know the Indians there. They had advanced into what is now Minnesota , wintered there with the Lakota and bought furs from them. Their method of seeking out the Indians in their areas as independent traders and transferring trade to them was considerably more successful in the years that followed than the settlements that suffered from the wars. But des Groseilliers and Radisson violated the royal monopoly that was now with the Compagnie des Indes Occidentales . After only three years, the company took action and banned individual trade.

Radisson and des Groseilliers tried to get permission from the French court in Paris . When this was denied to them, they went to London and turned to the English. Prince Rupert , a nephew of King Charles I of German descent , seized the opportunity, excited London businessmen and fitted out a ship. In June 1668, des Groseilliers set out, went to northern Quebec and established a small base on James Bay , the southern branch of Hudson Bay . The trade was extraordinarily successful. As early as 1669, the first batch of furs could be delivered to London and in 1670, at Prince Rupert's instigation , Charles II granted the 17 shareholders the charter , an extensive privilege not only for trade in Canada, but also for the complete self-administration of the Hudson's Bay Company, which was thus founded .

Explorations in the west, end of New France

The next few decades were also characterized by competition between the French and the English. In 1686 France attacked the Hudson's Bay Company trading post in James Bay. Both trading companies advanced westward into the uncharted continent. The French discovered the Ohio and Mississippi and established a large number of trading posts on both rivers. In 1682 Robert Cavelier de La Salle explored the full length of the Mississippi on behalf of Louis XIV and to promote the fur trade, was the first white man to reach its mouth near what is now New Orleans and founded the French colony Louisiana .

For the first time, the local tribes felt the sharp price fluctuations in fur and its consequences. Although the French led the Iroquois to a peace treaty, this first fall in fur prices meant that numerous licenses to trade fur were not renewed. In 1696 the fur trade on the western Great Lakes ended abruptly. Even Nicolas Perot , the commander of La Baye had the situation completely misjudged and forts like Fort St. Nicolas in Prairie du Chein, and Fort St. Antoine on Lake Pepin let the Mississippi built in 1685 and the 1686th The Mascouten felt cheated by the French, who could no longer pay the usual prices. They robbed Perot and several French people were killed.

A turn in the fur trade - Paris wanted to invest as little as possible - brought the appearance of Antoine Cadillac , who opened Fort Pontchartrain near Detroit to trade with all tribes of the Great Lakes. These moved into the area by the thousands. Potawatomi , Wyandot and Ottawa asked the approximately 1000 Fox and Mascouten to withdraw. The Fox Wars lasted from 1712 to 1716 and from 1728 to 1737 and almost resulted in the extermination of the Mascoutes. Until 1730 the British and French and the tribes involved played off against each other. In addition, smallpox epidemics raged, which in 1751 decimated the Mascouten to only 300 members.

The explorations continued in the 18th century. The official commission of Pierre Gaultier de la Vérendrye , from 1728 military commander of the Poste du Nord in Montreal, was to explore a route to the western ocean . De la Vérendrye advanced westward in two expeditions. In 1731 he came close to the Rocky Mountains in today's Wyoming , on the second attempt in 1738 to North Dakota and the upper reaches of the Missouri . Both times he established trade relations with the Indians, especially the Lakota , and established trading posts. Despite great financial returns of the Company from the fur trade in the new territories his trips were regarded as failures, because he had not reached the ocean.

In 1739 seven French traders reached Santa Fe , which was part of the viceroyalty of New Spain . However, it was not possible to establish stable trade relations over the long route through the deserts and steppes of New Orleans. In 1750 the Spaniards broke off contacts, imprisoned all the French on their territory and left no one or news outside their borders.

In the French and Indian War , the fighting on the North American continent as part of the Seven Years' War , France lost all possessions east of the Mississippi to England in 1763. The areas west of the river and the city of New Orleans were ceded to the Kingdom of New Spain . The French company gave up its interests, the fur traders of Montreal became independent or joined the English Hudson's Bay Company - or they challenged them, like Alexander Henry . Individual French traders remained active in New Orleans and founded St. Louis in 1764 , but they did not play a major role in trade at the time. St. Louis was not to become the center of the fur industry until the 19th century, but then under American leadership.

Organizational forms of trading companies

The fur trading companies operated in the wilderness, beyond state organization or social civilization - at least that was their point of view. But that does not mean that the trappers lived lawlessly. Though many of them had fled debt or prosecution, they established their own customs and laws and maintained strict discipline among themselves within their organization.

- The trading posts were run by a bourgeois . Trade expeditions that opened up new areas and visited Indian peoples were subordinate to a partisan , later usually called captain by American companies . Each of the two had unrestricted authority over their territory. Bourgeois were almost always involved in the company, they had personnel and financial responsibility for their trading area. Famous bourgeois were William Bent and Kenneth McKenzie , a well-known captain was Jedediah Smith .

- Each item had one or more clerks , the clerks were called. His duties included bookkeeping and warehousing , but he often had to take the goods out to Indian villages and accompany the exchanged furs to the posts. The most senior clerk was usually the bourgeois representative.

- Companies only used hunters or trappers on a large scale late. However, small groups of fur hunters have existed at all times. They went into the wilderness, often lived with the Indians and largely adapted their lifestyle to their culture. In territories of friendly peoples, they could spread out in small units, sometimes alone, on the rivers and streams; if there were conflicts, they either had to stay in the immediate vicinity of the posts or only went on hunting trips in larger groups.

- Camp Keepers were auxiliary workers to the trappers. On average, there was one camp keeper for every two hunters, whose job it was to skin the hunt, to clean, cut and dry the furs, and to provide for the hunters' livelihood.

- The voyageurs were recruited almost exclusively from the lower class of French descent, had no education and were mainly used for transport tasks. They powered the keelboats , broad ships used to transport goods and people on the shallow rivers of the American West, and the canoes used by traders and hunters to set out from the base. Astor found that a Canadian voyageur weighed three Americans on the rivers, while Chittenden replied that in the harsh wilderness (away from the rivers), an American trapper would be worth three voyageurs.

- The least respected and worst paid jobs were done by the Mangeurs de lard , the bacon eaters. They signed up for three or five years, got only bacon, dry bread and pea soup (hence the name) on the long trips, and their salary was so low that almost all of them were in debt to their employers at the end of their contract and extended their service life had to.

- A special position had the craftsmen and specialists, French Artisans called in the larger trading post. Blacksmiths, carpenters, boat builders and in later times on the great prairies also caravan drivers had a great deal of personal responsibility in their areas of expertise.

The salaries were generally low compared to the margins, the risks and the hard work. The best numbers are from the 19th century in the Missouri area. A clerk made about $ 500-1000 a year, trappers $ 250-400, camp keepers about $ 150-200. A voyageur got just $ 100, Mangeurs de lards a lot less. In addition to their work, some of the auxiliary workers had to support themselves from the country. They planted small fields next to the trading posts and occasionally went hunting. It is said that Voyageurs received what they received in kind: they contained corn mixed with some kidney fat or sebum - a little over a kilo a day, as well as two cotton shirts, a pair of heavy boots and a blanket per year. If a trapper or voyageur wanted to buy tobacco, sugar, or new tools, he had to shop in the post's warehouse at company prices.

Almost all those involved in the fur trade had in common that they lived for the day, salaries were mostly paid on payday. The rendezvous , large trade meetings in the 19th century, were orgy-like festivals of waste, which also played a major role in the spread of sexually transmitted diseases , especially syphilis , among the trappers and the Indians. Only a few trappers made the climb. Jedediah Smith, who worked his way up from hunter to captain and partner in a large trading company, and a few other successful colleagues are exceptions.

The hierarchies were strictly adhered to, the discipline was strict. Again and again traders, hunters or voyageurs tried to sell themselves with a load of furs and offer them to the competition. They were hunted down as deserters and severely punished. Fines increased debt and tied the employee to the company for longer, but there have also been reports of frequent use of the whip.

The pacific coast

When James Cook landed on Nootka Sound and Resolution Bay in 1778 , he noticed that there was fighting between the tribes, the main cause of which was the dispute over the trade monopoly with the foreigners. At the same time, from 1778 to 1794 the Spanish and British tried to enforce their claim to this stretch of coast. Chief Maquinna of the Mowachaht led a deliberate war and alliance policy. In doing so, he managed to control the regional fur trade, which in addition to prestige earned him European weapons.

When the journals of the Cooks expedition were published in 1784, this triggered a run on sea otter skins. Between 1785 and 1805 more than 50 merchant ships headed for the region. In 1788 the Spaniards founded a trading post. John Meares , whose four ships had been captured by the fleet of the Spanish captain Don Estevan José Martínez , brought a petition in the British House of Commons in 1790 , which encouraged the Prime Minister to drive the conflict to the brink of open war. The Spaniards gave up the northernmost settlement in the Pacific in March 1795 after being united with London.

The fur trade was part of a triangular trade between Europe, China and Northwest America. Since 1745, China had designated canton as the only trading center , more precisely its port Whampoa. In 1786 the traders from Boston had received a representation for the complicated trade there in Consul Samuel Shaw, in 1789 Thomas H. Perkins founded a fur trade agency. Only 13 Chinese, known as Co-hong, were allowed to trade directly with the Europeans. Almost all of the Perkins Company's fur trade was conducted through a certain Hoqua. Europeans sailed to the Nootka Sound with metalware, Venetian glass beads, and anything known to be coveted. They sold the otter and beaver furs in East Asia, where they made enormous profits to purchase porcelain , silk and other Chinese goods that were in demand in Europe. In the process, a trader's language was developed, which was called Chinook Wawa . It consisted of numerous Chinese, English, and Spanish words, but also words from the Chinook and Nuu-chah-nulth .

The supremacy of the Mowachaht was apparently broken by 1817 at the latest, and the trade in sea otter skins finally ended in 1825 due to overhunting. At the same time, the Tsimshian , Haida and coastal Salish fought long wars that were now fought with modern rifles.

From 1862 to 1863 a particularly severe smallpox epidemic raged on the west coast , probably killing 20,000 Indians. Most recently, John Douglas Belshaw estimated that British Columbia's indigenous population had collapsed from around 500,000 to below 30,000.

In Alaska the Russian-American company was initially predominant, which tried to enforce its trade monopoly against strong indigenous resistance with armed force. In the Three Saints Bay the first Russian settlement arose. From 1774 to 1791 Spain tried to assert its authority here too. The Russians also prevailed against the Tlingit in the Battle of Sitka in 1804 and subsequently monopolized the fur trade on the Pacific coast of Alaska. This happened for example through the sea otter war against the Tsimshian. In the hinterland, however, they could not dispute the Tlingit's monopoly on trade over the passes. In 1867 the US bought the area.

The big trading companies

Hudson's Bay Company

Main article: Hudson's Bay Company

In Rupert's Land , the largest area ever assigned to a private company, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) obtained a monopoly on the fur trade in 1670. But French fur traders contested this position, as did French traders from Montreal after the end of New France who had come together in the North West Company .

The first French explorer in Alberta was probably Joseph Bouchier de Niverville (1715-1804) in 1751, more precisely the ten men he had sent ahead to build Fort La Jonquiere. Anthony Henday (also Hendry) spent the winter of 1754/1755 with the Blackfoot and visited the Edmonton area . His account of the Siksika who kept horses met with disbelief. Samuel Hearne was the first to travel overland from Fort Prince of Wales on the Churchill River to the Coppermine River and on to the Arctic Ocean from 1770 to 1772 on behalf of HBC . He was the first to report on the Great Slave Lake . The willingness with which many of the Lake Wholdaia there brought Chipewyan furs to Hudson Bay and thus made themselves slaves in Hearne's eyes was explained by his leader Matonabbee by saying that the trade allowed them to give away generously and thus gain prestige.

The first British fort was built in 1778 by Peter Pond , a trader who worked for the North West Company, 50 km from the mouth of the Athabasca River . Alongside him, David Thompson , Alexander MacKenzie and George Simpson toured the region. For several decades the so-called Peddlers , independent, often French fur traders with good contacts to the Indians, were more successful than the HBC. This tried through forts to bring the area under their control. The first permanent fort was Fort Chipewyan , which MacKenzie founded in 1788. The first permanent settlement was Edmonton , founded in 1795 by the HBC.

In contrast to many other tribes in the northwest, the Blackfoot did not settle near the forts, because the existing trade structures also supplied them with the coveted goods. However, the first smallpox epidemic struck it from 1780 to 1782. Equally disastrous was the flu that hit Saskatchewan, the Athabasca, and the Peace Rivers in 1835. These epidemics caused the fur trade to collapse for years.

By 1800, many Métis moved to Manitoba and Alberta, some moved even further when the bison populations collapsed in Manitoba. Métis were of the utmost importance in supplying the forts with pemmican.

One focus of the HBC was in the Oregon Country , which the British and Americans claimed together from 1818 to 1846. The HBC received the exclusive right to trade with the "natives" in 1838 and founded a trading post in 1843 on the site of today's Victoria . It was secured by the border treaty between Great Britain and the USA of June 15, 1846, which struck Vancouver Island to British North America . London left the entire island to the company for ten years.

In 1849 James Douglas was appointed governor of the newly created crown colony of Vancouver Island by the HBC , of which Victoria became the capital. New Caledonia, as the mainland part of the later province was called, remained a territory under the administration of the HBC, which had to withdraw from the south.

But with the gold discoveries on the Fraser , 16,000 people came to Victoria in a very short time. Governor Douglas feared the loss of British influence. The British Colonial Office declared the mainland part of the Crown Colony of British Columbia , with New Westminster as its capital. Douglas was appointed governor of both colonies. During the Cariboo gold rush in 1861/62 tens of thousands streamed north again. The two colonies were merged on August 6, 1866 to form the United Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia , with Victoria as the capital.

The HBC promoted immigration from Great Britain. In 1861 he ordered reserve demarcations to be made, but the extent of the Indian reserves should be explained by the Indians themselves. This comparatively mild Indian policy ended in 1864 with Joseph Trutch , who in 1870 was the first to deny the "savages" any claim to land.

The numerous inlets made it possible to ship wood and coal by ship. This in turn encouraged the use of steamships. But the two banks that could have provided capital for agriculture had capital owners in Britain. The only bank with local capital was Macdonald's Bank , but it went bankrupt in 1864 after a robbery.

The influential British-Columbian HBC and colonial elite managed to achieve an undisputed position. In the name and through the HBC they held extensive land holdings, few families owned coal mines. The fur trade lost its importance in British Columbia, and there was no longer any need for London to continue to support the HBC monopoly that had been inherited, which was replaced with the establishment of Canada in 1869.

North West Company

Main article: North West Company

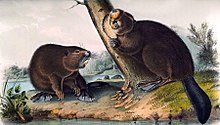

The fur trade had two roots in the Northwest Territories and the Yukon. Beavers , muskrats , mink , real marten and lynx were hunted by the inhabitants of the Mackenzie Basin, and later by those of the Delta. Trade expanded northwest from the 17th century. The second root was the hunt for the arctic fox . The first hunt was carried out by the Indians, the capture of the arctic fox skins by the Eskimos.

Cree raiders had hunted slaves since 1670, and their rifles often came from the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) trading post , York Factory . Thanadelthur, a young Indian woman, managed to escape to the fort in 1714, and the manager there, James Knight, immediately recognized the value of her information about fur hunters in the northwest. At his request, she led William Stewart and 150 Cree to the east arm of the Great Slave Lake and brokered peace between Chipewyan and Cree. So the HBC was able to establish a new trading post at Churchill, Prince of Wales ( Churchill ) on Hudson Bay . The peace allowed the Cree an undisturbed middleman trade between the HBC and the tribes living in the northwest.

In 1786, Fort Resolution near the confluence of the Slave River in the Great Slave Sea was the first trading post in the area of what will later become the Northwest Territories. When Alexander Mackenzie was looking for access to the Pacific, Lac La Martre was the first trading post to enable the Athapaskan tribes to trade directly with European companies. Until then, Cree and Chipewyan had acted as intermediaries. In addition, after 1700 Métis groups came from Saskatchewan who crossed the Methy Portage and whose descendants are now known as Northern Métis .

After the French were defeated by the British in 1760, several trading companies fought. The North West Company advanced north-west. Simon McTavish had connected nine small trading companies here. In 1786, the two rival companies of the North West Company under the leadership of Cuthbert Grant and Laurent Leroux of Gregory, Macleod and Company built separate forts. The companies united in 1787 built Old Fort Providence on Yellowknife Bay. Their headquarters were in Montreal , their central base was Grand Portage on Lake Superior .

But now the Hudson's Bay Company competed with the combined North West Company. This state of affairs did not end until 1821 after the Pemmican War , when it was forcibly merged into a company that was now known as the Hudson's Bay Company .

In 1796 a trading post was established on the Trout River , but the post had to be abandoned three years later after Inuit had killed its builder Duncan Livingston. In 1801 the North West Company split and the XY Company was created. Nevertheless, Ft. Simpson as the headquarters for the vast Mackenzie area. In 1827 alone, 4,800 beaver , 6,900 mink and 33,700 muskrat came to the HBC. The fact that the wars between Dogrib and Yellowknives, which lasted around half a century, ended with a peace agreement after 1823 also contributed to the increase in yields .

Fort Liard and Fort Halkett were built on the upper Liard River . This was intended to bypass the Russian middlemen who dominated Alaska to the Kaska Indians when trading across the Pacific coastal areas on the way through the inland. The remote posts were dependent on the Indians' supply of food, especially meat. Three expeditions led by Captain John Franklin explored the areas between the central Arctic coast and the slave lake (1825-1827, 1836-1839, 1845).

By 1850, the Indians were increasingly living near the trading posts. The traders increasingly gave credit to the hunters. The bigger the loot from earlier years, the higher the loans. For the Indians it became a kind of recognition of their hunting skills to get the highest possible credit and thus debt. The beaver fur (madebeaver) became the only currency in the area. Its exchange value was clear: 3 mink, 10 to 15 muskrat, a full-grown lynx or six swans corresponded to a Madebeaver . A single knife cost two Madebeavers.

American societies

In 1822, the US government abolished the factory system that had been in force west of the Mississippi since 1796, thereby dissolving the monopoly of government agencies. This gave private companies and individuals the opportunity to participate in the trade. The St. Louis-based Superintendent for Indian Affairs was responsible for issuing licenses . The Missouri and the Rocky Mountain Fur Company emerged as the first companies. In contrast to the British, they wanted to run the business bypassing the Indians with their own hunters, but this got them into serious conflicts. From 1825 rendezvous were organized in the mountains, during which the fur hunters handed over their skins to the company management and were provided with equipment and food for the next year. The following year, company founder Ashley sold his shares in Jedediah Smith , David E. Jackson and William Sublette . From then on, Ashley monopolized the trappers' equipment, the three new shareholders the trade - even if they had no formal monopoly.

Soon the company came under the spotlight of the American Fur Company , which dominated the fur trade in the east. This company, like its competitor, was a comparatively short-lived but momentous institution. It was founded in 1808 by Johann Jakob Astor with the support of US President Thomas Jefferson . The headquarters were in St. Louis , Detroit and Fort Mackinac , but Astor was located on a connection to the productive Pacific. For this purpose, the Pacific Fur Company was founded in 1810 , on whose behalf the Tonquin reached Columbia in 1811 and founded the Astoria settlement . The attempt to make Astoria the center of a trade network between China, Northwest America and Europe failed in the British-American War of 1812. Astor's agents forced and against his will sold the settlement to the Hudson's Bay Company.

Astor kept a close eye on the activities of American trappers in the 1820s, and he expanded his monopoly westward. So in 1826/27 he bought Pratte & Co and the Columbia Fur Company . But the beaver populations fell under the massive hunt, and the Hudson's Bay Company had even systematically cleared their populations on the Snake River . Jedediah Smith and his partners sold their company in 1830 and the Rocky Mountain Fur Company was now officially named. In 1832 alcohol was banned from trading with the Indians, a product that was now produced in secret stills. In 1834 Astor, who recognized the change in fashion in time, sold the American Fur Company , which was largely ousted by HBC in the next few years. In the same year, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company was dissolved, heavily in debt. The rendezvous took place through the American Fur Company until 1840.

The extreme northwest

The development in the extreme northwest was somewhat different. Alexander Mackenzie came into contact with the Gwich'in in 1789 , in 1806 Fort Good Hope was built there , around which the Gwich'in enforced a trade monopoly against the resistance of Inuit , who attacked the fort with 500 men (around 1826 to 1850).

Russians first appeared in Alaska in 1741 , and in 1763 Unangan killed around 200 residents of Unalaska , Umnak and Unimak Island , whereupon Russian vengeance for their part claimed 200 lives; more fights followed. In 1784 there was fighting on Kodiak between Russians and Tlingit, in 1804 the battle of Sitka . Despite their military superiority, the Russians were only able to partially enforce their fur trade monopoly, the Tlingit in many cases successfully defended themselves. The British leased the southeastern mainland from the Russians in 1838. The Spaniards, who also tried to enforce claims in the region, withdrew in 1819 with the Adams-Onís Treaty . In 1839 the first Russian trading post called Nulato was established on the lower Yukon. In the Yukon, two trading circles collided, the west of which was oriented towards the Pacific and thus China, while the east was dependent on the markets in Europe.

The question of whether the population has collapsed to the same extent due to epidemics as further south and on the coast from 1775 or (before) 1787 in Sitka can hardly be answered . It is known that an epidemic of smallpox raged in Alaska and on the Lynn Canal from 1835 to 1839 . In 1865 the HBC complained that some of the best and most important provisions hunters for the fort had died. When the British and Han met for the first time, their culture had already changed significantly, and the population was declining to an unknown extent.

Russian traders came to the lower Yukon by 1839/42 at the latest, British to the Mackenzie as early as 1806. Middlemen brought Russian and British goods into the region decades before the arrival of the first Europeans, with the Tlingit dominating this trade in the west, the Gwich'in in the Northeast. Rifles and glass beads, most of which were exchanged for furs, were in demand.

Due to falling prices for beaver fur, the HBC was forced to increasingly rely on rarer and more expensive fur. This caused the fur traders to move further north. John Bell therefore opened a post on the Peel River , later Fort McPherson . But the Gwich'in there, who wanted to use their new position as middlemen, had no interest in letting the British move further west. However, they did not succeed in preventing the loss of their advantageous position in the long term if they could hold HBC back for more than five years. Fort Yukon was built around 5 km above the mouth of the Porcupine in the Yukon in 1847 . Now the Indians there profited from the fur trade and worked against commission and European goods and the resulting reputation.

At the same time, the HBC started from the south, with Robert Campbell setting up trading posts at Dease and Frances Lake and the upper Pelly River in 1838/40 . Campbell opened a post at the confluence of the Pelly and Yukon rivers in 1848. However, in 1849 thirty Tlingit stopped its traders. Under these circumstances he failed to make a profit during his five years at Fort Selkirk , founded in 1848 ; however, he made contact with the Han, through whose territory he drove down the river to Fort Yukon. On August 19, 1852, the Chilkat looted and destroyed the post.

The HBC believed it had to establish trade contact with leading men, so-called trading chiefs . The Indians chose a trading chief , but they were not permanently bound by his instructions and they brought their furs to cheaper places depending on the availability. In addition, the HBC demanded that goods could no longer be awarded on credit . The Indians, however, saw barter not only as an exchange of goods, but also as a kind of gift trade, in which reputation and honor were important criteria. Therefore, they played the HBC and the Russian-American Company off against each other, because the British rightly feared a planned expansion of the Russians up the Yukon. The Indians, for their part, took advantage of conflicting interests between the Mackenzie district, where the British now enjoyed an undisputed trade monopoly, and Fort Youcon by threatening to supply this or that region - an advantage of their nomadic way of life. They also refused to deliver meat in order to enforce better conditions. A monopoly was not enforceable in the Yukon. When the Americans bought Alaska in 1867 and discovered that Fort Yukon was on their territory, the HBC had to evacuate the fort in 1869, and trade networks changed dramatically.

The Alaska Commercial Company enforced an extensive trade monopoly in the lower Yukon until 1874, but independent fur traders competed with it. The British granted the traders now without further credit. American competition offered better prices, sought out more distant groups, offered British goods and made the Indians independent partners. Moses Mercier founded the Belle Isle Post for the Alaska Commercial Company in 1882 . From 1883 monopoly, the ACC raised the prices of its own goods, lowered fur prices and limited lending.

The Americans also used steam boats, such as the Yukon or, from 1879, the 25 m long St. Michael of the Western Trading and Fur Company, which increased the quantities of goods. After the Klondike gold rush began , ships over 70 m long were added. With this gold rush, the fur trade suddenly became almost insignificant, especially since the up to a hundred thousand gold prospectors overwhelmed the fur animal stocks, as did all other meat-producing animals.

Regional special economic cycles

In contrast to Canada as a whole, the fur industry in the Yukon experienced a certain revival. In 1921 there were 27 trading posts from 18 different entrepreneurs; in 1930, at their peak, there were 46 posts from 30 entrepreneurs. The annual income fluctuated between 23,000 (1933) and over 600,000 dollars (1944-1946) extremely strongly. The massive unemployment during the Great Depression drove so many into the hunt that the fur market collapsed. In the 1940s, game stocks declined so much that hunting around Dawson was banned.

The decline

In 1947 and 1948 the fur market collapsed in the United States and Canada. It was not until 1950 that local monopolies known as trap lines were distributed in Yukon in order to end overhunting and to give the local Indians one of their few sources of income. In British Columbia, these hunting parcels had already been introduced in 1926.

Conflicts over fur production

From the 1970s onwards, there were disputes over the type of seal hunt in Canada, in which the killing of young animals was in the foreground. They also fell at a time of relative market saturation, so that fur sales collapsed. While 4.6 million fur animals were killed annually from 1970 to 1987, this number fell to 1.7 million by 1990. While the numbers barely increased in the following decade, the average prices doubled.

Today the fur industry is rather insignificant. In 1986, 3700 furriers worked in Canada, 2950 of them in Québec, 675 in Ontario and 75 in Manitoba. Many of them came from Kastoria, Greece . They were spread over 280 companies; in 1949 there were 642 with 6,700 employees. Their number fell to 2,350 by 1986.

After the end of the 1990s, production increased again with strong fluctuations. The Hudson's Bay Company, which is now primarily active in the retail, real estate and energy business, stopped selling fur products from 1991 to 1997.

present

Seal skins and pelts from Canada are subject to import restrictions in the USA and the European Union. The Canadian fur manufacturers strive for an ecological image under the slogan Fur is Green . The Canadian government rejected the European Union's offer of separation between traditional fishing by indigenous peoples and commercial fishing in 2009.

Overall, the concentration process in the fur industry continued. In 1974, 1,221 farms in the USA were still producing 3,328,000 mink skins , in 1994 the numbers fell to 484 and 2,623,000 respectively. Of these, around 900,000 were made in Wisconsin and over 500,000 in Utah . Although the number of farms fell to 274 by 2008, production stagnated at the same time. Their total value ranged from about $ 70 million to $ 185 million . Canada and the USA thus accounted for 4.9 and 6.0% of world production, respectively, in 2009, around 30% come from Denmark and almost 20% from China . In 2008 production fell by 13%.

While traditional trapping strongholds such as Québec and Ontario became less and less important, although a third of the total prey is still made here, production in animal farms rose sharply. Especially Nova Scotia leads the way here.

Research history

CVs like those of Jedediah Smith or Jakob Astor fit into the notion of the historiography of the late 19th century of an adventurous, individualistic, capitalist-risk-taker and diligent conquest of the “wilderness” through which the frontier, the settlement border, was pushed westward. For the Americans they stood at the beginning of the Wild West, the Indians were extras who had to give way to a superior civilization.

In the 1930s, Harold A. Innis in Toronto not only made the turn to a more independent historiography that broke away from the European and southern neighbors, but also gave the indigenous people an increasingly active economic role. This development was encouraged by the fact that in 1970 the Hudson's Bay Company Archives , which has the largest and oldest holdings, moved from London to Canada.

Alan W. Trelease: The Iroquois and the Western Fur Trade: A Problem of Interpretation from 1962 represented a fundamental change of direction in research , who for the first time did not understand the behavior of the Iroquois exclusively in economic terms. This understanding was mainly spread by the work of Innis, one of the most important historians of his time, who, however, still had to get by without the holdings of the archives of the Hudson's Bay Company. This finally broke away from mere economic determinism. However, adaptation to changing capitalist markets did exist. Less sedentary groups relocated to the trading posts and tried for their part to enforce local monopolies or to play the monopolists off against each other. Almost entrepreneurial thinking could be demonstrated by the Makah in northwest Washington by the 19th century at the latest .

Adrian Tanner was able to show for the Cree, however, that the hunt for their own needs was traditional and ritualized, while the commercial hunt for the trading companies was only slightly influenced by spiritual or ritual thinking. Other groups such as Métis and Ottawa switched to supplying trading posts with meat or garden products. In the sub-arctic and arctic regions in particular, the entire trade network depended on the goodwill of the Indian suppliers, and occasionally even defenders. Other groups overran the regional populations.

Nevertheless, an overview of the numerous strategies of the ethnic groups of North America is still lacking. Only a few groups have so far made it clear how they changed internally, how new leadership groups with new dependencies on the fur trade emerged. Since the relationships within the whites and between the groups were also changed, Sylvia Van Kirk spoke of a fur trade society. For example, the ritual trade created a kind of fictitious relationship, as Ray was able to show, which joined in the emergence of actual couple relationships, from which new cultural groups emerged. In the east from around 1800 women of mixed origins were increasingly preferred to pure Indian women, which led to a spatial separation, but also to a special awareness of the children. On the other hand, mixed groups within the tribes often formed their own core or they even formed separate new groups. In Canada this resulted in a separate group, the Métis, whose ethnogenesis has not yet been clarified.

Little research has been done into the effects of the fur trade on labor and gender relations among the ethnic groups participating in this economic activity. The work so far shows that the need for fur in some groups was so great that the women who were mostly responsible for this work not only invested more manpower and time, but that polygyny was strongly promoted as a result. The social rank of women was also undermined by missionaries and fur traders alike.

From 1820 onwards, the USA only accepted the categorization as white or native and thus choked off such a development. Children who had a British father were more likely to be encouraged to integrate in Canada, while French fathers predominantly felt they belonged to the cultural sphere of the mothers.

The internal perspective of the First Nations only came into play from the 1980s with their own works.

A similar development can also be observed for other social groups whose role in the fur trade has long received little systematic attention. In 2000, Susan Sleeper-Smith investigated the influence of denominations on the fur trade. In 1980, Sylvia van Kirk examined the role of Indian women and their often successful founding of families.

The role of epidemics, the spread of which was closely related to the fur trade, was also recently examined. For example, a 2011 study showed that French fur traders spread tuberculosis as early as the early 18th century, but the disease rarely broke out for almost two hundred years. The new infections were enough for the pathogens to survive in the indigenous groups. Only with the impoverishment policy towards the Indians of Canada and the USA, coupled with hunger, cold and poor living conditions, did tuberculosis break out again, which affected almost all tribes.

The Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly has been appearing as its own specialist magazine since 1965 , dealing exclusively with the history of the fur trade. The associated museum goes back to James Bordeaux Post in Chadron , Nebraska . One of the historic papers in Canada is called The Beaver .

literature

- Jennifer SH Brown: Strangers in Blood. For Trade Company Families in Indian Country. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver u. a. 1980, ISBN 0-7748-0125-5 .

- Hiram Martin Chittenden: The American Fur Trade of the Far West. A History of the Pioneer Trading Posts and early Fur Companies of the Missouri Valley and the Rocky Mountains and of the Overland Commerce with Santa Fe. 3 volumes. Francis P. Harper, New York NY 1902, ( Digitalisat Vol. 1 , Digitalisat Vol. 2 , Digitalisat Vol. 3 ; Reprint of the 1935 edition published by Press of the Pioneers, New York. With introduction and notes by Stallo Vinton and sketch of the author by Edmond S. Meany. (= Library of Early American Business & Industry. 61). 2 volumes. AM Kelley, Fairfield NJ 1976, ISBN 0-678-01035-8 ; first comprehensive publication on the subject).

- Eric Jay Dolin : Fur, Fortune, and Empire. The Epic History of the Fur Trade in America. WW Norton & Company, New York NY et al. a. 2010, ISBN 978-0-393-06710-1 .

- Lisa Frink, Kathryn Weedman (Eds.): Gender and Hide Production (= Gender and Archeology Series. 11). Alta Mira Press, Walnut Creek, CA et al. a. 2005, ISBN 0-7591-0850-1 .

- James R. Gibson: Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and China Goods. The Maritime Fur Trade of the Northwest Coast, 1785-1841. University of Washington Press, Seattle WA 1992, ISBN 0-295-97169-X .

- A. Gottfred: Femmes du Pays. Women of the Fur Trade, 1774-1821. In: Northwest Journal. Vol. 13, n.d. (1994-2002), ISSN 1206-4203 , pp. 12-24, online .

- James A. Hanson: When Skins Were Money. A History of the Fur Trade. Museum of the Fur Trade, Chadron NE 2005, ISBN 0-912611-04-9 .

- Erik T. Hirschmann: Empires in the Land of the Trickster. Russians, Tlingit, Pomo and Americans on the Pacific Rim, Eighteenth Century to 1910s. 1999, (PhD thesis, University of New Mexico 1999).

- Dietmar Kuegler : Freedom in the wild. Trappers, mountain men, fur traders. The American fur trade. Publishing house for American studies, Wyk auf Foehr 1989, ISBN 3-924696-33-0 (methods, personalities and companies in the fur trade).

- John G. Lepley: Blackfoot Fur Trade on the Upper Missouri. Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, Missoula MT 2004, ISBN 1-57510-106-8 .

- Richard Somerset Mackie: Trading Beyond the Mountains. The British Fur Trade on the Pacific. 1793-1843. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver 1997, ISBN 0-7748-0559-5 .

- Ray H. Mattison: The Upper Missouri Fur Trade: Its Methods of Operation. In: Nebraska History. Vol. 42, No. 1, March 1961, ISSN 0028-1859 , pp. 1–28, ( digitized version ; historical outline of the most contested hunting area in the 19th century).

- Carolyn Podruchny: Making the Voyageur World. Travelers and Traders in the North American Fur Trade. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln NE et al. a. 2006, ISBN 0-8032-8790-9 .

- Udo Sautter : When the French discovered America. Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 2012, ISBN 978-3-86312-009-2 .

- Sylvia Van Kirk: Many Tender Ties. Women in Fur-trade Society, 1670-1870. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman OK 1980, ISBN 0-8061-1842-3 .

- David J. Wishart: The Fur Trade of the American West. 1807-1840. A Geographical Synthesis. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln NE et al. a. 1992, ISBN 0-8032-9732-7 (Economic Geographic Study).

Web links

- Ann M. Carlos (University of Colorado), Frank D. Lewis (Queen's University): The Economic History of the Fur Trade: 1670 to 1870

- Exploration. the Fur Trade and Hudson's Bay Company , Early Canada Online

- Jacqueline Peterson, John Afinson: The Indian and the Fur Trade: A Review of Recent Literature , Manitoba History, No. 10, Fall 1985

- Hiram Martin Chittenden: The American fur trade of the Far West , University of Nebraska Press 1986, reprint of the 1935 edition Chittenden (1858–1917) provides a now outdated perspective.

- Lachine National Historic Site of Canada / Montreal

Remarks

- ↑ See Daniel Francis, Toby Morantz: Partners in Furs: A History of the Fur Trade in Eastern James Bay 1600–1870 , McGill-Queen's University Press, Kingston and Montreal 1983

- ↑ Arthur J. Ray: Fur Trade History as an Aspect of Native History , in: Ian AL Getty, Donald B. Smith (Eds.): One Century Later: Western Canadian Reserve Indians Since Treaty 7 , University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver 1978

- ^ Kuegler, p. 12.

- ↑ John F. Crean: Hats and the Fur Trade in: The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 28.3 (August 1962) 373-386, here: p. 379.

- ↑ Crean, p. 376

- ↑ Also called Sieur de Mons or Sieur de Monts .

- ↑ Lois Sherr Dubin: The History of Beads from 30,000 BC to the Present , London 1987, pp. 261-289.

- ^ Louise Deschêne: Le peuple, l'État et la guerre au Canada sous le régime français , Boréal, Montreal 2008, pp. 162f.

- ↑ Kuegler, p. 14

- ↑ Kuegler, p. 16

- ^ David Dary: The Santa Fe Trail - Its History, Legends, and Lore , Alfred A. Knopf, New York 2001, ISBN 0-375-40361-2 , p. 35.

- ↑ Chittenden p. 69

- ↑ Chittenden, p. 58

- ↑ Chittenden, p. 62, Kuegler, p. 27.

- ↑ Kuegler, p. 24

- ↑ Dee Brown, In the west the sun went up (original title: The Westerners) , Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1974, ISBN 3-455-00723-6 , p. 61.

- ^ Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown: The Chinook Indians: Traders of the Lower Columbia River , University of Oklahoma Press, 1976, pp. 77f.

- ↑ The range of this epidemic is shown on this archived map ( memento from August 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) from the Seattle Times .

- ↑ See John Douglas Belshaw: Cradle to Grave. A Population History of British Columbia , University of British Columbia Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7748-1545-1 .

- ↑ Jonathan R. Dean: The Sea Otter War of 1810: Russia Encounters the Tsimshians , in: Alaska History 12/2 (1997) pp. 25-31.

- ↑ An overview map of the HBC area can be found here ( Memento from October 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ See Joseph Bouchier de Niverville . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ). .

- ^ John Blue: Alberta. Past and Present. Historical and Biographical , Vol. 1, Chicago 1924, p. 16

- ↑ Anthony Hendey . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ).

- ^ Government of Alberta - About Alberta - History

- ^ John Blue: Alberta. Past and Present. Historical and Biographical , Vol. 1, Chicago 1924, p. 19

- ↑ Samuel Hearne . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ).

- ^ Strother Roberts: The life and death of Matonabbee: fur trade and leadership among the Chipewyan, 1736–1782 , Manitoba Historical Society, 2007.

- ^ In addition, the excavation report by Robert S. Kidd: Archaeological Investigations at the Probable Site of the First Fort Edmonton or Fort Augustus, 1795 to Early 1800s , Calgary 1987.

- ↑ Maurice FV Doll, Robert S. Kidd and John P. Day examined the situation of the Métis at the end of the 19th century: The Buffalo Lake Métis Site: A Late Nineteenth Century Settlement in the Parkland of Central Alberta , Calgary 1988

- ^ Reuben Ware: The Lands We Lost. A History of Cut-Off Lands and Land Losses from Indian Reserves in British Columbia , Union of BC Indian Chiefs, Vancouver 1974, 4f.

- ↑ General on the history of the fur trade, particularly the North West Company, in the northwest: The Fur Traders , McGill University, 2001 .

- ↑ Thanadelthur . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ).

- ^ Shepard Krech III: The Death of Barbue, a Kutchin Trading Chief , in: Arctic 35/2 (1962), pp. 429-437.

- ^ Robert Boyd: The coming of the spirit of pestilence. Introduced infectious diseases and population decline among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774-1874 , University of Washington Press, Seattle 1999, pp. 23f.

- ↑ Ken S. Coates: Best Left as Indians. Native-White Relations in the Yukon Territory, 1840-1973 , McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal, Kingston 1991, Paperback 1993, pp. 8-14

- ↑ Osgood, p. 5.

- ↑ Osgood, p. 12

- ↑ Ken S. Coates: Best Left as Indians. Native-White Relations in the Yukon Territory, 1840-1973 , McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal, Kingston 1991, Paperback 1993, pp. 56f.

- ↑ Ken S. Coates: Best Left as Indians. Native-White Relations in the Yukon Territory, 1840-1973 , McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal, Kingston 1991, Paperback 1993, p. 58, tab. 4

- ^ Fur Industry , in: The Canadian Encyclopedia .

- ↑ [1] Back in Style: The Fur Trade, KATE GALBRAITH, December 24, 2006 The New York Times

- ^ [2] Fur is Green Campaign in Canada under Nothing to fear but fur itself, Nathalie Atkinson, National Post, October 31, 2008

- ↑ http://www.fur.ca/index-e/news/news.asp?action=news&newsitem=2009_03_27 ( Memento from April 22, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) EU votes for a full ban on seal products, Injustice is served : EU Council favors political expediency over science and law, press release of the Fur Institute of Canada, Ottawa, March 27, 2009.

- ^ Mink Production in the United States, 1969-2010

- ↑ World Mink Production Slips for First Time in Decade , October 23, 2008.

- ↑ Statistics Canada ( memo of December 29, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), archive.org, December 29, 2011.

- ^ Alan W. Trelease, The Iroquois and the Western Fur Trade: A Problem of Interpretation , Mississippi Valley Historical Review 49 (1962) 32-51. Similar to Bruce G. Trigger: The Children of Aataentsic , 2 vol., McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal 1976, on the Hurons

- ↑ Ray: Competition and Conservation in the Early Subarctic Fur Trade , in: Ethnohistory 25 (1978), showed that they did this long ago, at least in the 18th century .

- ^ Robert L. Whitner: Makah Commercial Sealing, 1869-1897. A Study in Acculturation and Conflict , in: Rendezvous: Selected Papers of the Fourth North American Fur Trade Conference, 1981. pp. 121-130.

- ^ Adrian Tanner: Bringing Home Animals: Religious Ideology and Mode of Production of the Mistassini Cree Hunters , St. Martin Press, New York 1979

- ^ Richard L. Haan: The 'Trade Do's Not Flourish as Formerly': The Ecological Origins of the Yamassee War of 1715 , in: Ethnohistory 28 (1981), pp. 341-358

- ^ Ray: Reflections on Fur Trade Social History and Métis History in Canada , in: American Indian Culture and Research Journal 6/2 (1982), pp. 91-107

- ↑ Jennifer SH Brown: Strangers in Blood: fur trade company families in Indian country , UBC Press, 1980

- ↑ Tanis C. Thorne: The Osage: An Ethnohistorical Study of Hegemony on the Prairie-Plains or Janet Lecompte: Pueblo, Hardscrabble, Greenhorn: The Upper Arkansas, 1832-1856 , Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1978

- ↑ The groups at James Bay, which go back to white and Indian ancestors, have only accepted the self-designation Métis for a few decades.

- ↑ Frink, pp. 206f.

- ↑ Jennifer Brown: Children of the Early Fur Trades and Jennifer Brown: Women as Center and Symbol in the Emergence of Métis Communities , in: Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 3/11 (1983), pp. 39-46. Sylvia Van Kirk: What if Mama is an Indian ?, The Cultural Ambivalence of the Alexander Ross Family , in: Foster (Ed.): The Developing West: Essays on Canadian History in Honor of Lewis H. Thomas , University of Alberta Press, Edmonton 1983, pp. 123-136

- ^ As Donald F. Bibeau: Fur Trade Literature from a Tribal Point of View: A Critique , in: Thomas C. Buckley (Ed.): Rendezvous: Selected Papers of the Fourth North American Fur Trade Conference, 1981 , North American Fur Trade Conference, St. Paul 1983, pp. 83-92

- ^ Susan Sleeper-Smith: Women, Kin, and Catholicism. New Perspectives on the Fur Trade , in: Ethnohistory 47/2 (2000), pp. 423-452

- ^ Sylvia van Kirk: "Many Tender Ties": Women in Fur-Trade Society in Western Canada, 1670-1870 . Watson & Dwyer Publishing, Winnipeg 1980

- ↑ Fur traders brought tuberculosis to North America , in: Welt online, April 5, 2011