Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain ( [samɥɛl də ʃɑ̃plɛ̃] ) (* 1574 in Brouage or La Rochelle as Samuel Champlain ; † December 25, 1635 in Québec , Canada ) was a French explorer and colonizer. He and Pierre Dugua de Mons are the founders of New France and Champlain was the first governor of this colony.

Coming from a family of sailors, Champlain began exploring the east coast of North America in 1603 . From 1604 to 1607 he was involved in the first French colonization efforts in Nova Scotia . In 1608 he founded a settlement on the Saint Lawrence River from which the city of Québec developed. Champlain was the first European to discover Lake Champlain , named after him . He published maps and reports, also drawing on stories from the natives and the French who lived with them. In addition, he entered into alliances with the Montagnais , Algonquin and Wyandot and pledged to support them in their wars against the Iroquois . On his travels he reached the Huron Lake . In 1620, by order of King Louis XIII, finished Champlain . his explorations and from then on devoted himself to the administration and the targeted colonization of New France. He founded trading companies that transported goods (mostly furs) to France and contributed to the growth of the colony until his death.

biography

Childhood and youth

Champlain's year and place of birth have always been controversial. It is certain that he was the son of Antoine Champlain (in some records also written Chappelain or Chapeleau ) and Marguerite Le Roy. Brouage in the province of Aunis (the mother's hometown) and La Rochelle are considered possible birthplaces . There were several different opinions among historians about the year of birth, ranging from 1567 to 1580. According to a baptism certificate found by the genealogist Jean-Marie Germe in 2012, Champlain was baptized on August 13, 1574 in La Rochelle in the Protestant church of Saint-Yon. So he would not have become a Catholic until a few years later .

The Champlains were a family of sailors. Samuel learned to navigate, draw nautical charts , and write reports. Since every French fleet had to provide for its own defense at sea, he also learned how to use firearms. He acquired this knowledge while serving in the royal army from 1594 to 1598, during the final phase of the Huguenot Wars in Brittany . Back then, as quartermaster, he was responsible for feeding and caring for horses. It is possible that at the end of 1594 he was involved in the siege of Fort Crozon near Brest , which was captured by the Spanish. In 1597 he served at Quimper as a capitaine d'une compagnie ("Captain of a company").

First experience

His from Marseille originating in-law uncle Guillaume Allène whose ship had been hired in 1598 to the according to the Peace of Vervins Spanish troops to Cadiz zurückzutransportieren, gave Champlain the opportunity to accompany him. After a long stay in Cadiz, the ship accompanied a Spanish fleet to the Caribbean and the coast of Central America . Champlain gained further experience in the process. When he crossed the Isthmus of Panama and saw the Pacific Ocean , he came to the conclusion that a canal at this point could be a worthwhile project. During the two-year trip he made detailed notes and wrote an illustrated report which he presented to King Henri IV on his return . Champlain was awarded an annual pension as a reward. The report was first published in 1870. Its authenticity has been questioned on various occasions due to inaccuracies and deviations from contemporary sources; but now it is assumed that Champlain was actually the author.

When Champlain returned to Cádiz in August 1600, his sick uncle-in-law offered him to take over the business. When he died in June 1601, he inherited a considerable fortune. It comprised an estate near La Rochelle, a warehouse in Spain and a 150-ton merchant ship. The inheritance and the royal pension gave the young researcher a high degree of independence, as he did not have to rely on financial support from traders and investors. From 1601 to 1603, Champlain served as a geographer at the royal court . His duties included traveling to the French ports to learn as much as possible about North America from fishermen . The fishermen sailed the coast between Nantucket and Newfoundland seasonally to benefit from the rich fishing grounds. He also wrote a study of earlier failed attempts at colonization by the French, including by Pierre de Chauvin at Tadoussac . Chauvin lost his fur trade monopoly in North America to Admiral Aymar de Chaste in 1602 . Champlain then asked him for a post on the first crossing, which he received with royal approval.

Expeditions to North America

During his first trip to North America, Champlain was an observer on a fur trading expedition led by François Gravé du Pont . Du Pont had a great deal of experience in North American waters as he had regularly sailed there for several years for trade. Three ships set sail in Honfleur in mid-March 1603 and reached Tadoussac on May 24th. Three days later, Du Pont and Champlain met at the Pointe aux Alouettes, at the mouth of the Rivière Saguenay , with representatives of the Montagnais , the Maliseet and the Algonquin . They agreed on an alliance that would shape the relationship between the French and indigenous people over the next few decades. From mid-June they followed Jacques Cartier's route six decades earlier: they explored the lower reaches of the Rivière Richelieu and reached the Lachine rapids on the Saint Lawrence River . After his return to France in September, Champlain published the travelogue Des sauvages, ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l'an 1603 (“About the savages, or journey of Samuel Champlain from Brouages in New France in 1603 ").

In the following year, Champlain joined another expedition led by Du Pont, organized by Pierre Dugua de Mons , who had obtained the monopoly on the fur trade. After leaving Le Havre in March 1604 , they reached the coast of Nova Scotia just under two months later . De Monts commissioned Champlain to look for a suitable place for winter quarters. After exploring the Bay of Fundy , his choice fell on Saint Croix Island , a small island at the mouth of the St. Croix River . The crew was poorly prepared for the severe winter; by the spring of 1605 almost half died of scurvy . The settlement was then moved to Port Royal . For the next two years, Champlain used this site as a base for further explorations that took him south to Martha's Vineyard Island . Skirmishes with the Nauset prevented him from establishing a permanent settlement on Cape Cod (near present-day Chatham ). In May 1607, De Monts learned that the king had revoked his monopoly, so he had to abandon the colonization efforts.

Founding of Québec and fighting against the Iroquois

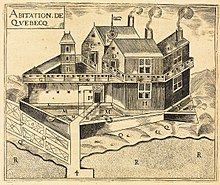

When he agreed to build a trading post on the St. Lawrence River and to develop land for French colonies, De Monts was granted a renewal of his monopoly. At his own expense, he equipped three ships that left Honfleur on April 13, 1608. Champlain, who had previously been without an official function on the trips, commanded the Don de Dieu . On June 3, the ships anchored in Tadoussac. The crew continued up the river in boats and landed on July 3 at Cap Diamant near the mouth of the Rivière Saint-Charles . At what is now Place Royale , the men built a complex of buildings surrounded by a palisade and a moat. This Habitation de Québec was a fortress, residence and trading post in one and formed the cornerstone of the future city of Québec .

Due to illness, only nine out of 29 men, including Champlain, survived the first winter in Québec. After receiving supplies, he renewed his existing alliances with the indigenous people and formed a new one with the Wyandot . In return, the tribes demanded support in the fight against the Iroquois who lived further south . Accompanied by nine French soldiers and about 300 warriors, he left Québec on June 28, 1609 and went up the Rivière Richelieu. On July 12th, he was the first European to discover Lake Champlain , which was later named after him . Since they had not yet met an Iroquois, over three-quarters of the companions turned back there. On the evening of July 29th, the group finally encountered about 200 Iroquois between Ticonderoga and Crown Point . These attacked the following morning but fled when three chiefs were shot with arquebuses (two of them by Champlain himself).

From October 1609 to April 1610, Champlain stayed in France to report to De Monts and the king. When he was back in Québec, his allies asked him again for assistance against the Iroquois. About a hundred of them were holed up in a fort at the mouth of the Rivière Richelieu, near today's Sorel . With the help of five arquebuses, almost all Iroquois were killed or captured on June 19. As a result of this one-sided battle, there were no further armed conflicts over the next twenty years. Champlain sent Étienne Brûlé to the Wyandot to study their way of life. In Québec he learned of the king's assassination. His widow Maria de 'Medici , who as regent instead of the nine-year heir to the throne Louis XIII. ruled, showed little interest in New France, and prevented many of Champlain's Protestant patrons from entering the courtyard. He therefore went to France in August in order to establish new political relations for the benefit of the colony.

Marriage and expeditions inland

In the signing of a marriage contract on December 27, 1610, Champlain saw an opportunity to improve his access to the royal court. In it he committed himself to marry the then twelve-year-old Hélène Boullé, the daughter of a secretary in the royal household. The marriage was concluded three days later in the Paris church of St-Germain-l'Auxerrois . Since she had not yet reached the legal age, it was agreed that she would only be allowed to move in with him after two years. The marriage contract was probably the first document on which he signed “de Champlain”; whether he was actually raised to the nobility at the time is uncertain. In May 1611, Champlain returned to Québec. He went to the Île de Montréal and set up a temporary fur trading post at Pointe-à-Callière (location of the future city of Montreal ). He noted the upstream Île Sainte-Hélène , which he named after his wife, as a suitable location for a possible city foundation, but ultimately nothing emerged from these plans. In September 1611 he was back in France.

Since they could no longer maintain their monopoly, De Mont's business partners were no longer willing to support the Colony of Québec. Champlain drew a map of New France and asked the king for government funding. Louis XIII. appointed on October 8, 1612 Charles de Bourbon Viceroy of New France, who in turn appointed Champlain as his lieutenant. His task was to build an administration, to negotiate contracts with the indigenous people or to wage war against them, to curb the illegal fur trade, to find the "easiest route to China and East India" and to find and exploit valuable metals. Charles de Bourbon died a little later and his successor Henri de Bourbon confirmed Champlain in office. In March 1613, Champlain found in Québec that the fur trade had not been very profitable as the Indians increasingly rejected the activities of unauthorized traders. From the Île de Montréal, he followed the Ottawa River in May and was the first European to describe it in detail. In June he visited Chief Tessouat on the Isle des Allumettes and offered him to build a fort for his people near the Lachine Rapids. Tessouat turned down this offer because he could better control trade on the river from the island.

Champlain was back in France as early as August 1613. He published the travelogue Les voyages du Sieur de Champlain, Saintangeois, capitaine ordinaire pour le Roy en la Marine ("The voyages of Mr. de Champlain from the Saintonge , ordinary captain of the king in the Navy"), in which he made his research trips from 1604 to Described in 1612. At the beginning of 1614, when he was staying with the king in Fontainebleau , he united the merchants of La Rochelle and Saint-Malo in a joint company, the Compagnie des Marchands de Rouen et de Saint-Malo (also known as Compagnie de Champlain ). On his next crossing to Québec in May 1615, he also brought Franciscan missionaries of the Recollect Order with him. Possibly accompanied by Étienne Brûlé, he followed the route of his last expedition to the Isle des Allumettes in July and then moved on over Lake Nipissing and the French River until he reached Lake Huron on August 1st .

A month later, Champlain joined a Wyandot war expedition against the Iroquois on Lake Simcoe . The group crossed Lake Ontario and followed the Oneida River until they reached a fortified settlement on Onondaga Lake (on the northwestern edge of present-day Syracuse ) on October 10, 1615 . The planned surprise attack failed. Champlain was injured in his leg by two arrows and broke off the ensuing siege on October 16. Reluctantly, he accepted the Wyandot's offer to spend the winter with them on Lake Simcoe. During a hunting trip in December, he got lost in the forest and was only found three days later. He stayed until the end of May to study the Wyandot way of life, after which he returned to France via Québec, where he arrived in September 1616.

Administration and settlement of New France

Henri de Bourbon had meanwhile been imprisoned, but his successor as viceroy, Pons de Lauzières , left Champlain in office. He made another trip to Québec in 1617, which lasted only three months. Among other things, he took the first permanent settlers with him, the family of his friend, the pharmacist Louis Hébert . After regent Maria de Medici was disempowered and her adviser Concino Concini was shot , political conditions stabilized. Champlain wrote two reports which he sent to the King and the Chamber of Commerce in February 1618. He wrote that it was easy to get to China and East India via New France and that tariffs on Asian merchandise that could be levied in Québec would more than ten times the revenue generated in France. The Christian faith can also be spread among countless souls. Champlain recommended that the Québec trading settlement be expanded into a heavily fortified port city and that 300 families should settle there. The Chamber of Commerce was immediately convinced of the plans, whereupon the king promised any necessary support. Champlain's short trip to New France in 1618 served primarily in preparation for the settlement project.

Some business partners of the Compagnie des Marchands de Rouen et de Saint-Malo , who intrigued against Champlain, refused to let him on board in Honfleur in March 1619. When the Royal Council got involved, society complied and accepted him as their superior. Henri de Bourbon was released after three years of imprisonment and received all privileges back. Since he no longer showed any interest in New France, he sold the viceroy title to his brother-in-law Henri II. De Montmorency in October 1619 . When Champlain sailed back to Québec in the spring of 1620, he brought his now 22-year-old wife Hélène Boullé with him. In the meanwhile dilapidated settlement, he had new, more permanent buildings built. He also ordered the construction of the first fortress, Fort Saint-Louis above the rock face of Cap Diamant. In May 1621 he learned that the fur trade monopoly had passed to the de Caën brothers' company. A looming conflict could be averted by the two rival societies merging. Champlain also exerted influence on the politics of the Montagnais by enforcing that a chief could only be elected with the consent of the French. In the autumn of 1624 he went back to France. His wife, who did not like the harsh life in North America, left Québec forever and entered a monastery years later; the marriage remained childless.

Even Henri de Lévis , the new viceroy, confirmed Champlain in February 1625 as his lieutenant. Cardinal Richelieu viewed colonies as a means of strengthening France and consolidating royal power; He considered the previous activities of private entrepreneurs to be insufficient. In 1627 he put the administration on a completely new basis and founded the state-controlled trading company Compagnie de la Nouvelle France , which undertook to bring 4,000 settlers to New France over the next 15 years. Both Champlain and Richelieu were among the slightly more than 100 partners. From March 21, 1629 on, Champlain was in command of New France and the Cardinal's direct subordinate; although his activity corresponded to that of a governor, he never held that title.

Last years

The company's first supply fleet set sail in April 1628, but was considerably delayed. Champlain, who had wintered in Québec, discovered that the supply situation was becoming increasingly precarious. At the beginning of July, English traders looted a farm on Cap Tourmente that he had built two years earlier to supply Québec. During the Thirty Years' War France and England entered a mutual state of war. King Charles I had issued letters of piracy, after which privateers began attacking French ships and colonies in North America. On July 10, Basque fishermen brought a call for surrender on behalf of the adventurer David Kirke . Champlain was not impressed by this, whereupon the fleet refrained from attacking. However, they hijacked the supply fleet, so that Québec had to get by for another winter without supplies.

In the spring of 1629 the supplies were slowly running out and Champlain was forced to send some residents to Gaspé or to Indian settlements to stretch the food rations. On July 19, Kirke's fleet appeared outside Québec, and Champlain had no choice but to surrender and allow himself to be captured along with the rest of the residents. During a long stop in Tadoussac, he learned that Étienne Brûlé had defected to the enemy. In October he pointed out to the French ambassador in London that Kirke's conquest of Québec had been illegal, as the state of war had already ended in April with the signing of the Peace of Susa. In March 1632, the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye was signed, which confirmed the French claim to Acadia and Québec. In the same year, Champlain published Voyages de la Nouvelle France , an account of his activities from 1603 to 1629 (which he dedicated to Cardinal Richelieu), and Traitté de la marine et du devoir d'un bon marinier , a treatise on leadership, seamanship and navigation .

On March 1, 1633, Champlain again took over the post of commandant of New France. He sailed one last time to Québec, where he arrived on May 22nd after a four-year absence. He led the rebuilding of Québec, which had been devastated by the English. On his behalf, the Sieur de Laviolette (whose exact identity is still controversial) founded the town of Trois-Rivières in July 1634 at the mouth of the Rivière Saint-Maurice . In the same month he sent Jean Nicolet on a long exploration trip to the Great Lakes region . In 1635, Champlain's health deteriorated noticeably; he finally passed away on December 25th.

memory

Several geographical objects in Canada, but also in the US states of New York and Vermont , were named after Champlain. There are also numerous buildings and monuments that bear his name. Below is a selection:

- Lake Champlain (Lac Champlain) : important lake between New York, Vermont and Québec

- Champlain Valley (Vallée du Lac Champlain) : the valley in which the lake is located

- Champlain Sea : former inlet of the Atlantic at the end of the last glacial period

- Pic Champlain : mountain in the province of Québec

- Champlain : City in New York State

- Champlain : city in the province of Ontario

- Champlain : municipality in the province of Québec

- Samuel de Champlain Provincial Park : Protected Area in Ontario

- Pont Champlain : Bridge over the Saint Lawrence River in Montreal

- Champlain Bridge : Bridge over the Ottawa River in Ottawa

- Château Champlain : Hotel in Montreal

literature

- David Hackett Fischer: Champlain's Dream . Simon and Schuster, New York 2008, ISBN 978-1-4165-9332-4 .

- Raymonde Litalien, Denis Vaugeois (Ed.): Champlain. The Birth of French America . McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal 2004, ISBN 0-7735-2850-4 .

- Samuel Eliot Morison : Samuel de Champlain. Father of New France . Little Brown, New York 1972, ISBN 0-316-58399-5 .

- Cicero T. Ritchie: The First Canadian. The Story of Champlain . St. Martin's Press, New York 1962.

- Hans-Otto Meissner : Scouts on the St. Lawrence River. The adventures of Samuel de Champlain retold according to old documents . Cotta, Bertelsmann, Stuttgart, Gütersloh 1966. (Bertelsmann 1976. Other frequent editions, also with changing subtitles)

- Conrad E. Heidenreich, K. Janet Ritch: Samuel de Champlain before 1604. Des Sauvages and Other Documents Related to the Period. McGill-Queen's University Press, Toronto 2010.

Movies

- Champlain , 1964, directed by Denys Arcand

Web links

- Marcel Trudel: Samuel de Champlain . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ).

- Champlain: Travels in the Canadian Francophonie (English, French)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Janet Ritch: Discovery of the baptismal certificate of Samuel de Champlain. (No longer available online.) Champlain Society, 2013, archived from the original on December 5, 2013 ; accessed on April 17, 2014 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. P. 62.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. P. 65.

- ↑ Vaugeois: Champlain: the birth of French America. P. 87.

- ↑ Harold Faber: Great explorations - Samuel de Champlain . Benchmark Books, Tarrytown (New York) 2005, ISBN 0-7614-1608-0 , pp. 10 .

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. P. 586.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 98-100.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 100-117.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 121-123.

- ^ Marcel Trudel: François Gravé du Pont . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ).

- ↑ Baie-Sainte-Catherine: Un important site historique. (No longer available online.) Encyclobec, 2003, archived from the original on December 31, 2014 ; Retrieved April 17, 2014 (French). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Samuel de Champlain: Des sauvages, ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l'an 1603. archive.org, accessed on April 17, 2014 (English).

- ↑ George MacBeath: Pierre Dugua De Monts . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ).

- ^ The History of Chatham, Cape Cod, Massachusetts. (No longer available online.) My Chatham, 2009, archived from the original on October 31, 2013 ; accessed on April 17, 2014 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Québec, nouvelle terre française (1608–1755). (No longer available online.) City of Quebec, archived from the original on April 18, 2014 ; Retrieved April 17, 2014 (French). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Jacques Lacoursière: Le 3 juillet 1608 - La fondation de Québec: les Français s'installent en Amérique du Nord. Fondation Lionel-Groulx, October 13, 2011, accessed September 4, 2014 (French).

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 297-316.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 577-578.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 282-285.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 287-288.

- ^ Elsie McLeod Jury: Tessouat . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ).

- ^ Scan , the work (Paris 1613) online

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 330-333.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 348-350.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 353-355.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 364-365.

- ^ Marie-Emmanuel Chabot: Hélène Boullé . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ).

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 404-410.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 409-412.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 412-415.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. Pp. 418-421.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. P. 418.

- ↑ Fischer: Champlain's Dream. P. 447.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Champlain, Samuel de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French explorer and colonizer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1574 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Brouage or La Rochelle |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 25, 1635 |

| Place of death | Quebec , Canada |