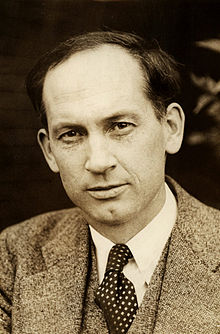

Harold Adams Innis

Harold Adams Innis (born November 5, 1894 in Otterville , Ontario, † November 8, 1952 in Toronto , Ontario) was a Canadian professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and author of numerous works in the fields of media theory , communication theory and Canadian economic history . According to him, that's Innis College named at the University of Toronto. Innis, whose style is considered dense and difficult, is considered one of the most influential Canadian intellectuals. Innis was instrumental in developing the Staples Thesis , which assumes that Canada's culture, political history and economy were largely shaped by the exploitation and export of a range of Staples such as skins , fish , wood , grain , metals and fossil fuels .

Innis' works on communication theory deal with the role of the media in shaping a culture and developing civilizations. One of his best-known theses is the assumption that the balance between oral and written communication forms the growth of Greek culture in the 5th century BC. BC favored. In his view, western civilization is currently endangered by influential, advertising-driven media and by present- centeredness and the continuous systematic, ruthless destruction of permanently important elements for cultural activities.

Innis was the cornerstone of a humanities study that looked at the social sciences from a specifically Canadian point of view. As chairman of the Department of Political Economy at the University of Toronto, he tried to build a cadre of Canadian humanities scholars to break the dependency of Canadian universities on UK and US-educated professors who were ignorant of Canadian history and culture. Innis opened up sources of funding for the Canadian humanities.

Innis tried to make universities independent of political and economic pressure. He believed that independent universities as centers of critical thinking were essential for the survival of Western culture. His student and college colleague Marshall McLuhan described Innis death in 1952 as a catastrophic loss to human understanding. McLuhan wrote: I am delighted to think of my own book The Gutenberg Galaxy as a footnote in the observations on Innis and the physical and social consequences, first in writing, then in printing.

Training and military service

First years of life

Harold Adams Innis was born on November 5, 1894, on a small dairy farm near the township of Otterville , Oxford County , southwest Ontario . The life habits and processes of the farm shaped his later life. His mother Mary Adams Innis , who, like his father William, was a devout Baptist, called him Herald in the hope that he would pursue a career as a Baptist clergyman . At the beginning of the 20th century, Baptism took on a formative role in rural areas, as it gave isolated families a sense of community, embodied the values of individualism and freedom, and because its widely dispersed congregations were not controlled by centralized, bureaucratic authorities, Enjoyed encouragement. Innis later became an agnostic , but never lost his interest in religion. According to his friend and biographer Donald Creighton (1902–1979), Innis' character was shaped by the Church:

The strict sense of values and the feeling of devotion to something that would become so characteristic of him in his later life was based at least in part on the instructions that were so zealously and unquestionably given to him in the unadorned walls of the Baptist church in Otterville .

Innis attended the one-room school in Otterville and the ward high school. To complete his secondary education at a Baptist college, he commuted 20 miles to Woodstock by rail . He intended to become a teacher in a state school and passed the entrance exams for teacher training, but decided to work for a year in order to have the financial resources necessary for training. At the age of 18 he decided to teach for a semester in the one-room school in Otterville until the school board could hire a fully qualified teacher for the post. During his work he became convinced that life as a teacher in a small, rural school was not for him.

University studies

In October 1913, Innis began attending McMaster University in Toronto. Because McMaster was Baptist and attended by many ex-Woodstock College students, it was the most suitable position for Innis. The humanities professors there encouraged him to think critically and to debate. Innis was primarily influenced by James Ten Broke, who brought up an essay question Innis spent his life dealing with: Why do we pay attention to the things we pay attention to?

The year before he graduated from McMaster University, Innis spent a summer teaching at the Northern Star School's agricultural border community in Landonville, near Vermillon , Alberta , during which he became aware of the size of Canada. He obtained information about western problems with high interest rates and transportation costs. Innis was mainly concerned with history and economics. His guiding principle was a comment by history lecturer WS Wallace, which said that the economic interpretation of history is not the only possible, but the most profound.

Military service

After graduating from McMaster University , Innis joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force on a religious basis . In the autumn of 1916 he was sent to France to fight in the First World War . The Protect grave warfare with mud, lice and rats had a devastating effect on Innis.

His role as an artillery operator gave him an up-close experience of living (and dying) on the front lines, especially when he was involved in the successful Canadian attack at the Battle of Arras . Radio operators or observers had the task of observing the point of impact of projectiles and providing corrective information. On July 7, 1917, Innis was hit by a splinter in the right thigh, whereupon he had to be treated in England for eight months.

Innis was no longer used in the war after being wounded. Biographer John Watson noted that physical wounds took seven years to heal, but psychological damage persisted for life. As a result of the war, Innis suffered from depression and nervous exhaustion.

Watson found that World War I strengthened Innis nationalism, heightened his sense of the destructive effects of technology, including the communications media used to “sell” the war, and first raised his doubts about the Baptist faith.

Graduated from McMaster and Chicago

In April 1918, Innis earned a Master of Arts degree from McMaster University. This qualifying pamphlet, titled The Returned Soldier , dealt with the public principles necessary to assist veterans cope with the effects of war and carry out the reconstruction of the state.

In August 1920, Innis received a PhD from the University of Chicago . In the two years he was working on his dissertation, his interest in economics deepened, after which he decided to become an economist. The Chicago School of Economics questioned what it regarded as abstract and universalistic theories of neoclassical economics , the main criticism being that general economic rules should be based on specific case studies.

Innis was influenced by George Herbert Mead and Robert E. Park at the University of Chicago , although he did not attend their courses. Innis was mainly concerned with their thoughts that communication contains more aspects than the transfer of information. James W. Carey noted that Mead and Park characterized communication as the process by which culture is created, maintained, and institutionally shared.

In Chicago, Innis came into contact with Thorstein Veblen's theses , who sharply criticized contemporary thinking and culture. Although Veblen had left Chicago a few years earlier, his theses had a strong presence. In a later essay, Innis praised Veblen for waging war against the standardized, static economy .

In Chicago, Innis gave some introductory courses in economics. One of his students was Mary Qualye, whom he married in May 1921. Innis, who was 26 years old at the time of marriage, and Quayle, who was 22 years old at the time of marriage, had four children, Donald (1924), Mary (1927), Hugh (1930) and Ann (1933).

History of the Canadian Railroad Company CPR

In his PhD dissertation entitled A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway , Innis dealt with the history of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). The completion of the first Canadian transcontinental railroad in 1885 was of great importance for the development of Canada. Innis' theses, published in a book in 1923, represent an early attempt to explain the importance of the railroad from an economic historian's point of view. Innis used extensive statistics in support of his arguments and found that the difficult-to-implement and expensive project was aided by fears of a US annexation of the Canadian West.

Innis put forward the thesis that the history of the Canadian Pacific Railway was above all the history of the spread of western civilization over the northern half of the North American continent. Robert Babe noted that the railroad carried industrialization, coal transportation and construction materials and, as a communication medium, promoted the spread of European civilization. Babe interprets Innis' theses to the effect that for Innis the establishment of the CPR meant a massive, energy-consuming, fast-moving, powerful, capital-intensive sign that was placed in the midst of natives whose whole life was thereby disturbed, if not even destroyed in the end.

According to communication scientist Arthur Kroker , Innis tried to demonstrate in his work on CPR that technology is not something external to the Canadian being, but on the contrary, the necessary condition and ongoing consequence of the Canadian existence. Innis continued the preoccupation with the application of political and economic force begun in A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway throughout his career. Innis investigation ends with a summary of the criticism of western Canada's economic policy, in particular high transport costs and rising import tariffs, which were intended to support Canadian manufacturers. Residents of western Canada complained that it channeled money from prairie farmers to the east coast economy. Innis stated that western Canada is paying the price of developing Canadian nationality and it appears that it should continue to pay it. Eastern Canada's greed does not seem to be waning.

Main work

field research

In 1920 Innis took up a position at the Department of Political Economy at the University of Toronto , where he held courses in trade, economic history and economic theory. He decided to concentrate his research on the then little worked area of Canadian economic history. The first topic Innis dealt with was the fur trade. Furs had lured French and English traders to Canada and motivated them to advance along the vast rivers and lakes west to the Pacific coast. Innis realized that not only would he be able to rely on archival materials to understand the history of the fur trade, but he would have to travel the country himself to get first hand information and - as he put it - Gathering dirt experience .

For this purpose, Innis traveled in the summer of 1924 with a friend in a five and a half meter long, canvas-covered canoe from the Peace River across Lake Athabasca , the Slave River to Dreat Slave Lake , on a tug of the Hudson's Bay Company over the Mackenzie River to the Arctic Ocean . During his travels, Innis also gathered information about other raw materials such as wood, paper, minerals, grain and fish. By the early 1940s, Innis had toured all parts of Canada except for the western Arctic and the eastern side of Hudson Bay .

On his travels, Innis mainly interviewed people who were active in raw material production and had their stories told.

The Fur Trade of Canada

Innis deepened his study of the relationships between empires and colonies in the 1930 book The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History , which covers the beaver fur trade from the 16th century to the 1920s. In contrast to conventional historians, who heroically described the exploration of the Canadian continent by European adventurers, Innis dealt with the effects of the interrelationships between geography, technology and economy on the fur trade and Canadian politics and economy. Innis notes that Canada's fur trade largely set borders and that the country was created not in spite of the geographic situation, but because of it.

The Fur Trade of Canada (in later editions The Fur Trade in Canada ) describes in the second part the cultural interactions between three groups of people: The Europeans in European metropolises, who viewed beaver fur hats as a fashionable luxury item; the European settlers, who viewed beaver pelts as a raw material that could be exported to purchase essential goods from their home countries; and the indigenous peoples , who traded in fur to purchase industrial goods such as metal pots, knives, rifles and liquor. Innis describes the role of the locals as central to the development of the fur trade. Without their hunting techniques, knowledge of the area and tools such as snowshoes, sleds and canoes, the fur trade could not have developed. European technologies have had a profound impact on First Nations societies . Innis wrote: The new technology with its radical innovations brought about as rapid a change in the Indian cultures as the extermination of people through war and disease. Historian Carl Berger suggests that Innis, placing the indigenous people at the center of his analysis of the fur trade, was the first to portray the disintegration of primitive society as a result of European capitalism.

Unlike much of the historians who equated the beginning of Canadian history with the arrival of Europeans, Innis emphasizes the cultural and economic contributions of the First Nations. Innis wrote that we did not realize that the Indian and its culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.

In the closing section, Innis emphasizes that the best way to understand Canadian economic history is to examine how one commodity was replaced by another. The dependence on raw materials made Canada dependent on more industrialized countries, the cyclical changes from one main raw material to another caused severe upheavals in the Canadian economy.

Cod fishing

After publishing his study of the fur trade, Innis turned to an older example, the cod fishery that had been practiced for centuries on the North American east coast, particularly the Newfoundland Bank. The study was published in 1940 under the title The Cod Fisheries: The History of an International Economy . The study summarizes the more than 500-year history of the exploitation of cod as a raw material and the associated conflicts between empires. While The Fur Trade in Canada mainly focused on the interior of the continent with its vast rivers and lakes, The Cod Fisheries focuses on global trade and the far-reaching effects of a commodity, both on central regions and on peripheral colonies such as Newfoundland , Nova Scotia and New England .

Communication theories

His studies of the impact of connected rivers and lakes on Canadian development and Europe prompted Innis to examine the complex economic and cultural relationships between transportation systems and communications. During the 1940s, Innis was involved in paper, an industry of vital importance to Canada. This investigation formed a crossroads between his preoccupation with raw materials and his communication studies. The biographer Paul Heyer wrote that Innis traced paper through its subsequent stages: newspapers and journalism, books and advertising. In other words, he shifted his perspective from the resource-based industry to a cultural industry where information, and ultimately knowledge, is a product that circulates, has value, and gives power to those who own it.

One of Innis' first studies in communication theory applied the dimensions of time and space to various media. Innis partitioned media in time binding and space-binding media. Time-binding media are durable, they contain clay or stone tablets. Space-binding media are short-lived. They include modern media such as radio, television, and tabloids.

Innis studied the rise and fall of ancient empires by analyzing the effects of communication media. He looked at media that had grown an empire, sustained it through its prime, and the changes in communications that led to its downfall. Innis sought to show that media "alignments" in terms of space and time affected the complex mechanisms necessary to maintain an empire. These mechanisms include the partnership between knowledge and ideas necessary to create and maintain an empire and the power (or strength) needed to expand and defend it. Innis saw the interaction between knowledge and power as a crucial factor in understanding an empire.

Innis believed that the balance between the spoken word and writing contributed to the heyday of Greek culture in the time of Plato . The balance between the time-oriented medium of language and the space-oriented medium of writing was thrown when the oral tradition became less important than the dominance of writing. During this phase of transition, Rome took over the predominance of the Mediterranean from the Greek cultures.

Innis saw his analysis of the effects of communication on the rise and fall of the rich led to warn of the crisis of Western civilization. The development of powerful communication media such as tabloids had shifted the balance in favor of space and power and pushed back time, continuity and knowledge. The balance necessary for cultural survival had been brought into imbalance by what Innis called mechanized communication media, which are used for the rapid transmission of information over great distances. These media had promoted a focus on the present , which displaced the past or future.

Innis summarized his conclusions as follows:

The crushing pressures of mechanization, which can be seen in newspapers and magazines, have led to the creation of communication monopolies. Their established positions involve the continuous, systematic and ruthless destruction of elements essential to cultural activity.

Innis believed that Western civilization could only be restored by restoring the balance between space and time. He further assumed that this was done by restoring the oral tradition in universities, coupled with the liberation of institutions of higher learning from political and economic pressures. In his essay, A Plea for Time , Innis suggested that serious dialogue in universities could evoke the critical thinking necessary to restore the balance between power and knowledge. Then the universities could muster the courage necessary to attack the monopolies threatening civilization.

Academic career and public perception

Influence in the 1930s

In addition to his study of the cod fishery, Innis wrote various texts in the 1930s on raw materials such as metals and grains and the economic problems of Canada during the Great Depression . Innis toured western Canada in the summer of 1932 and 1933 to research the effects of the Depression. In the following year, Innis, in the essay The Canadian Economy and the Depression, described the situation of a country that is exposed to international problems and the regional differences that make it impossible to implement effective solutions. He described the situation of a prairie economy that is dependent on grain exports, is beset by drought and the growing influence of large cities and is at the same time supported by the export of raw materials. The result of this situation was political conflict and a break in federal-provincial relations. There is a lack of information on which to base forward-looking policies for this situation. since the position of the social sciences in Canada is very weak .

Innis' reputation as a "public intellectual" grew steadily, and in 1934 Prime Minister Angus L. Macdonald invited him to serve on a Royal Commission to investigate Nova Scotia's economic problems . The following year Innis helped found The Canadian Journal of Economics and Politival Science . In 1936 Innis received a full professorship at the University of Toronto and a year later became head of the Department of Political Economy.

In 1938, Innis was named president of the Canadian Political Science Association . In his inaugural address, entitled The Penetrative Powers of the Price System , he attempted to understand the destructive effects of modern technology as it changed from an industrial system based on coal and iron to a system of the latest industrial energy sources, electricity, oil and steel. In the second part, Innis attempted the commercial effects of tabloids made possible by advanced printing techniques and those of the new medium radio, which threatens to circumvent the walls erected by tariffs and to cross borders that hold back other communication media. Innis believed that both media stimulate consumer product cravings and promote nationalism.

Politics and the Great Depression

The era of the Dirty Thirties , characterized by mass unemployment, poverty and hopelessness, encouraged the emergence of new political groups. In Alberta, under the leadership of the radio preacher William "Bible Bill" Aberhart, the populist Social Credit Party was formed and won the 1935 election. Three years earlier in Calgary , Alberta, social reformers had founded the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), which advocated democratic socialism and a mixed economy with state-owned core industries. One of the founders was Frank Underhill , a colleague of Innis at the University of Toronto. Innis and Underhill were both members of a group at the university who described themselves as: Dissatisfied with the policies of the two major parties in Canada and tried to build a unified body of progressive opinion . In 1931, Innis presented the group with a study on economic requirements in Canada , but later distanced himself from party politics and active humanities scholars like Underhill.

Innis was of the view that humanities scholars should not become politically active, but should instead deal with public problems and then the production of critical thinking through knowledge. Innis saw the universities as institutions which, through dialogue, openness and skepticism, could produce free thinking and free research. Innis wrote: The university could provide such an environment, as free as possible from orientations and the institutions that make up the state, so that intellectuals can seek and explore other perspectives.

Although Innis sympathized with the western peasants and urban unemployed workers and their problematic situations, he did not turn to socialism. Eric Havelock , a leftist colleague of Innis, stated a few years later that Innis mistrusted imported solutions, especially Marxist analyzes and their emphasis on class struggle . He also fears that as a result of a weakened Canada connection with Great Britain, the country would come under the influence of American ideas instead of developing its own ideas based on the specific Canadian situation. Havelock added:

He was called the radical conservative of his day - not a bad name for a complex mind, far-sighted, cautious, possibly pessimistic in areas where thinkers we would call "progressive" would have had greater difficulty in finding a point of view, never satisfied with it to pick just one or two elements of a complicated equation and quickly develop a method or program based on that; Reaching far enough in the intellect to grasp the total sum of the factors and to understand their often opposing factors.

Late work

In the 1940s, Innis reached the zenith of his influence in both academic circles and Canadian society. In 1941 he helped found the US-based Economic History Association , later named second president, and its Journal of Economic History . Innis played a central role in both the founding of the Canadian Social Science Research Council in 1940 and in the founding of the Humanities Research Council of Canada in 1944. Both organizations became important sources of funding for academic research.

1944 awarded the University of New Brunswick and his alma mater, McMaster University Innis honorary degrees. In 1947 and 1948, Innis received honorary degrees from Universite Laval , the University of Manitoba and the University of Glasgow .

In 1945 Innis spent a month in the Soviet Union , where he was invited on the occasion of the establishment of the Russian Academy of Sciences . In his essay Reflections on Russia , Innis compared the Soviet producer economy to the Western consumer ethic :

An economy that emphasizes consumer goods is characterized by communications industries driven by advertising and by constant efforts to reach the greatest possible number of readers or listeners; an economy that emphasizes product goods is characterized by communications industries that are largely dependent on government support. As a result of this contrast, common public opinion in Russia and the West is difficult to achieve.

His trip came shortly before the conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union led to the Cold War . Innis lamented this rise in international tension. He saw the Soviet empire as a stabilizing counterweight to the US emphasis on commercialism and individual and constant change. For Innis, the Soviet Union was a society in the western tradition. He rejected the nuclear arms race and saw it as the triumph of force over knowledge, a modern form of the Medieval Inquisition . The Middle Ages burned its heretics and the modern age threatens them with atomic bombs , Innis wrote.

In 1946 Innis was elected President of the Royal Society of Canada , which represents the country's senior scholars and humanities scholars. In the same year he served on the Manitoba Royal Commission on Adult Education and published Political Economy in the Modern State , a collection of speeches and essays that reflected both his research on raw materials and his works on communication theory. In 1947, Innis was appointed Dean of Graduate Studies at the University of Toronto. In 1948 he lectured at the University of London and Nottingham University . Innis also held the Beit Lectures at Oxford University and later published the book Empire and Communications . In 1948 he became an elected member of the American Philosophical Society . In 1949 Innis was appointed a committee member of the Royal Commission on Transportation , a post that required extensive travel while his health gradually deteriorated. In the last decade of his career, Innis was isolated from the scientific community because a large number of economists could not relate his work on communication theory to his studies on raw materials. The biographer John Watson hypothesized that the near complete lack of a positive response contributed to his overwork and depression.

Harold Adams Innis died of prostate cancer on November 8, 1952, a few days after his 58th birthday. The Innis College at the University of Toronto and the Innis Library at McMaster University are named after Innis.

Innis and McLuhan

Marshall McLuhan was a colleague of Innis at the University of Toronto. Innis added McLuhan's early book The Mechanical Bride to the reading list of the fourth year economics course. McLuhan took up Innis' idea that when studying the effects of communication media, technological form is more important than actual content. Biographer Paul Heyer wrote that Innis' concept of "alignment" can be seen as a less flamboyant forerunner to McLuhan's phrase, "The medium is the message" ( Understanding Media , 1964). Innis tried to show that printed media like books or newspapers are oriented towards control of space and secular power, while media like a stone or clay tablets are oriented towards continuity and metaphysics or religious knowledge. McLuhan put the main focus on perceptual orientation, noting, for example, that newspapers address the reason of the eye while the radio address the irrationality of the ear. The difference in the approaches of Innis and McLuhan was summarized by James W. Carey as follows: Both Innis and McLuhan assumed the centrality of communication technology, in what way they differ, are the principal types of effects that they see caused by this technology. While Innis assumes that communication technologies mainly affect social organization and culture, McLuhan assumes that they mainly change sensory organization and thinking. McLuhan says a lot about perception and thinking and little about institutions; Innis says a lot about institutions and little about perception and thinking. Graeme Patterson countered this position, arguing that Innis was intensely concerned with perception and thinking, while McLuhan was intensely concerned with institutions. Patterson sees a common feature of Innis and McLuhan in the fact that both dealt with language, a fundamental institution of humanity.

The biographer John Watson sees Innis work as largely political, while McLuhan's work is apolitical. Watson writes that the mechanization of knowledge, not the relative sense orientation of the media, is key to Innis' work. This also underlines the politicization of Innis' position as opposed to McLuhan's. Innis believed that very different media could produce similar effects. For Innis, the United States' yellow press and the Nazi loudspeaker had the same negative effect: they reduced people from thinking beings to mere automation in a chain of commands. Watson points out that McLuhan differentiated media according to their sense orientation, while Innis differentiated them according to another type of relationship, the dialectic of power and knowledge in specific historical circumstances. Watson sees Innis' work more flexible and less deterministic than McLuhan's work.

Innis and McLuhan, as humanities scholars and teachers, were faced with the dilemma of publishing many books, but believing that book culture would evoke fixed points of view and homogeneous thinking. In the introduction to the 1964 reprint of The Bias of Communication , McLuhan highlighted Innis' technique of juxtaposing his insight into a Mosaic structure of seemingly incoherent and disproportionate sentences and aphorisms . McLuhan hypothesized that the reason Innis' texts are difficult to read is a pattern of knowledge that is not packaged for consumer taste . Inni's method is closer to the natural form of conversation or dialogue than to written discourse. It produces "insight" and "pattern recognition" rather than "classified knowledge" which is overrated by humanities scholars. McLuhan, who himself praised Innis' use of the Mosaic Access .

Innis theories of political economy, media and society had a significant influence on media studies and communication theory and, in conjunction with the work of Marshall McLuhan, developed a new approach that interprets media as the key to historical developments and changes and emphasizes the role of communication in history .

Works

- A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway . Revised edition (1971). Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1923

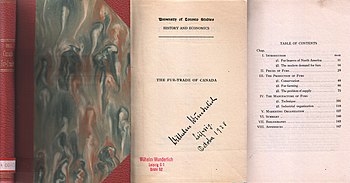

- The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History . Edited edition (1956). Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1930 → Table of Contents 1973 edition

- Peter Pond, Fur Trader and Adventurer . Toronto: Irwin & Gordon, 1940

- The Cod Fisheries: The History of an International Economy . The Ryerson Press, Toronto 1940

- Empire and Communications . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1950

- The bias of communication . University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1951

- The Strategy of Culture . University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1952

- Changing Concepts of Time . University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1952

- Essays in Canadian Economic History . Arr. Mary Q. Innis. University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1956

- The Idea File of Harold Adams Innis . Edited by William Christian. University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1980

- Harold A. Innis: Crossroads of Communication. Selected contributions. Karlheinz Barck (ed.); A contribution by Eric A. Havelock Harold A. Inniss, the philosopher of history. A memorial , other articles by Innis, Translator Fredericke von Schwerin-High. Springer, Vienna 1997 (table of contents at German National Library )

literature

- CR Acland, WJ Buxton: Harold Innis in the New Century . McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal 1999

- I. Angus: The Materiality of Expression: Harold Innis' Communication Theory and the Discursive Turn in the Human Sciences. In: Canadian Journal of Communication, 1998, 23, 1, pp. 9-29

- WJ Buxton: Harold Innis' Excavation of Modernity: The Newspaper Industry, Communications, and the Decline of Public Life. In: Canadian Journal of Communication, 1998, 23, 3, pp. 321-39

- TW Cooper: McLuhan and Innis: The Canadian Theme of Boundless Exploration. Journal of Communication, 1981, 31, 3, pp. 153-61

- R. Collins: The Metaphor of Dependency and Canadian Communications: The Legacy of Harold Innis . In: Canadian Journal of Communication, 1986, 12, 1, pp. 1-19

- R. de la Garde: The 1987 Southam Lecture: Mr. Innis, is there life after the "American Empire"? In: Canadian Journal of Communication (Special Issue), 1987, pp. 7-21

- D. McNally: Staple Theory as Commodity Fetishism: Marx, Innis, and Canadian Political Economy. In: Studies in Political Economy, 6, 1981, pp. 35–63

- William Melody, Liora Salter, Paul Heyer, (Eds.): Culture, Communication and Dependency: The Tradition of HA Innis . Ablex, Norwood (New Jersey) 1981

- R. Salutin: Last Call From Harold Innis . In: Queen's Quarterly, 1997, 104, 2, pp. 245-59

- Judith Stamps: Unthinking Modernity: Innis, McLuhan and the Frankfurt School . McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal 1995

- T. Varis: Culture, Communication, and Dependency: A Dialogue with William H. Melody on Harold Innis , in: Nordicom Review, 1993, 1, pp. 11-14

- Robert Babe: The Communication Thought of Harold Adams Innis . In Canadian Communication Thought: Ten Foundational Writers . University of Toronto Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8020-7949-0 , pp. 51-88

- Carl Berger: Harold Innis: The Search for Limits . In The Writing of Canadian History . Oxford University Press , Toronto 1976 ISBN 0-19-540252-9 , pp. 85-111

- JW Carey: Space, Time and Communications: A Tribute to Harold Innis . In Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society . Routledge, New York 1992 ISBN 0-415-90725-X , pp. 142-72

- JW Carey: Harold Adams Innis and Marshall McLuhan. The Antioch Review, 1967, 27, 1, pp. 5-39

- Donald Creighton: Harold Adams Innis: Portrait of a Scholar . University of Toronto Press, 1957 OCLC 6605562

- Olive Dickason, David MacNab: Canada's First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times . Fourth Edition. Don Mills, Oxford University Press, Ontario 2009 ISBN 978-0-19-542892-6

- WT Easterbrook, MH Watkins: Introduction and Part 1: The Staple Approach. In Approaches to Canadian Economic History . The Carleton Library Series. Carleton University Press, Ottawa 1984 ISBN 978-0-88629-021-4 ( limited preview in Google Book search)

- Paul Heyer: Harold Innis . Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham (Maryland) 2003 ISBN 978-0-7425-2484-2

- Mary Quayle Innis: An Economic History of Canada. Ryerson, Toronto 1935 OCLC 70306951

- Arthur Kroker: Technology and the Canadian Mind: Innis / McLuhan / Grant . New World Perspectives, Montreal 1984 ISBN 978-0-312-78832-2 full text

- Marshall McLuhan: Introduction to the Bias of Communication: [Harold A. Innis first edition 1951.] In Marshall McLuhan Unbound , Vol. 8. Gingko Press, Corte Madera CA 2005 OCLC 179926576

- Graeme Patterson: History and Communications: Harold Innis, Marshall McLuhan, the Interpretation of History . University of Toronto Press, 1990 ISBN 0-8020-6810-3

- Robin Neill: A New Theory of Value: The Canadian Economics of HA Innis . University of Toronto Press, 1972 ISBN 978-0-8020-0182-5

- Vancouver Public Library Ed .: "The Bias of Communication" and "The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History. In: Great Canadian Books of the Century . Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver 1999 ISBN 978-1-55054-736 -8th

- Alexander John Watson: Marginal Man: The Dark Vision of Harold Innis . University of Toronto Press, 2006 ISBN 978-0-8020-3916-3

Web links

- Literature by and about Harold Adams Innis in the catalog of the German National Library

- From transport to transformation, Innis and the media theory of civilization by Frank Hartmann

- Innis by Robin Neill, University of Prince Edward Island , in EH.Net Encyclopedia, Economic History Association. Edited by Robert Whaples, 2005

- Harold Adams Innis: The Bias of Communications & Monopolies of Power by Marshall Soules, Malaspina University-College, 2007 at Vancouver Island University

- Innis and the Emergence of Canadian Communication / Media Studies , by Robert E. Babe, University of Western Ontario , in "Global Media Journal", Canadian Edition ISSN 1918-5901 (English) ISSN 1918-591X (Français) Vol. 1, H. 1, 2008, pp. 9-23.

- Old Messengers, New Media: The Legacy of Innis and McLuhan, a virtual museum Exhibition at Library and Archives Canada , Archiv (click on the language button you want)

Individual evidence

- ^ WT Easterbrook, MH Watkins: "The Staple Approach" . in Approaches to Canadian Economic History . Ottawa: Carleton Library Series, Carleton University Press, 1984, pp. 1-98.

- ^ Robert E. Babe, "The Communication Thought of Harold Adams Innis," in Canadian Communication Thought: Ten Foundational Writers . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000, pp. 51-88.

- ^ Paul Heyer: Harold Innis . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2003, p. 66.

- ↑ a b Harold Innis: Changing Concepts of Time . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1952, p. 15.

- ↑ Alexander John Watson: Marginal Man: The Dark Vision of Harold Innis . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006, pp. 14-23.

- ↑ Harold Innis: "A Plea for Time" . in The Bias of Communication. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1951, pp. 83-89.

- ^ Marshall McLuhan: Marshall McLuhan Unbound. Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press v. 8, 2005, p. 8. A reprint of McLuhan's introduction to the 1964 edition of Inni's book The Bias of Communication first published in 1951.

- ↑ Donald Creighton: Harold Adams Innis: Portrait of a Scholar . University of Toronto Press, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Watson, pp. 50-51.

- ^ Robert Babe: Canadian Communication Thought: Ten Foundational Writers , University of Toronto Press, p. 51.

- ^ Creighton, p. 19.

- ↑ Creighton, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Watson, pp. 64-68.

- ↑ Watson, p. 326. Innis refers to this question in the preface to The Bias of Communication, a collection of essays on consciousness and communication.

- ↑ Creighton pp. 26-27.

- ↑ Creighton p. 28.

- ↑ Creighton, p. 31. Creighton wrote that Innis believed that if German aggression went unpunished, there would be a catastrophic effect on Christian hope in the world. Innis wrote to his sister: If I didn't trust Christianity, I - I think - would not go.

- ↑ Quoted from a later letter from Innis, Creighton, p. 107.

- ↑ Creighton, pp. 34-35.

- ^ Watson, p. 70.

- ↑ Watson, pp 68-117.

- ↑ Watson, p. 93. Watson notes that 240,000 Canadians died and 600,000 were wounded in World War I, significantly shaping Inni's generation.

- ^ Watson, p. 94.

- ^ Watson, p. 111.

- ^ JW Carey: "Space, Time and Communications: A Tribute to Harold Innis" . in Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society . New York: Routledge, 1992, p. 144.

- ↑ Innis wrote in an essay in 1929 "Veblen has waged a constructive war against the now dangerous tendency towards standardized, static economics on a continent with ever increasing numbers of students demanding books on ultimate economic theory". The essay was republished in Innis, Essays in Canadian Economic History , pp. 17-26.

- ^ Paul Heyer: Harold Innis . Lanham, Md: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc .. 2003, pp. 5 & pp. 113-15.

- ^ Watson, p. 119.

- ↑ Heyer pp. 6-7.

- ^ Harold Innis: A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Revised ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971, p. 287.

- ↑ Babe, p. 62.

- ^ Arthur Kroker: Technology and the Canadian Mind: Innis / McLuhan / Grant. Montreal: New World Perspectives, 1984, p. 94.

- ↑ Innis, pp. 290-94.

- ↑ Creighton, pp. 49-60. The reference to earthly experience appears in Watson, p. 41.

- ↑ Creighton, pp. 61-64.

- ^ Carl Berger: The Writing of Canadian History: Aspects of English-Canadian Historical Writing: 1900-1970. Toronto: Oxford University Press. 1976, pp. 89-90.

- ^ Watson, p. 124.

- ^ Carl Berger: The Writing of Canadian History . Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1976, pp. 94-95.

- ^ Harold Innis: The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History . Revised Edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1956, pp. 392-93.

- ↑ Watson, pp. 152-53.

- ↑ Innis: Fur Trade , pp. 10-15

- ^ Innis: Fur Trade , p. 388.

- ↑ Berger, p. 100.

- ↑ Olive Dickason, David McNab: Canada's First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times . Fourth Edition. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press, 2009, S.ix.

- ^ Innis: Fur Trade , p. 392.

- ^ Robin Neill: A New Theory of Value: The Canadian Economics of HA Innis . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972, pp. 45-46.

- ↑ Harold Innis: (2007 edition) Toronto: Dundurn Press, pp. 23-24. see also: Graeme Patterson: History and Communications: Harold Innis, Marshall McLuhan, the Interpretation of History . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990, pp. 32-33

- ^ Watson, p. 248.

- ↑ Heyer, p. 30.

- ↑ Innis: Empire , p. 27.

- ^ Watson, p. 313

- ↑ Innis: Empire , pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Innis: Empire , p. 104. See also: Heyer, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Harold Innis: The Bias of Communication . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1951, p. 87.

- ↑ Innis: Bias , pp. 61–91. The comment about universities mustering their courage appears in "The upside of ivory towers" by Rick Salutin. Globe and Mail , September 7, 2007.

- ^ Creighton, p. 84.

- ↑ Harold Innis: Essays in Canadian Economic History , edited by Mary Q. Innis. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1956, pp. 123-40.

- ↑ Creighton, pp. 85-95.

- ↑ Heyer, p. 20.

- ↑ Innis, Essays , pp. 252-72.

- ↑ Eric Havelock: Harold Innis: A Memoir . Toronto: Harold Innis Foundation, 1982, pp. 14-15. The reference to distancing Underhill is in the biography of Creighton p. 93.

- ↑ Quoted in "The Public Role of the Intellectual", by Liora Salter and Cheryl Dahl, in Harold Innis in the New Century. , McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal, 1999, p. 119.

- ↑ a b after Heyer, p. 33.

- ^ Watson, p. 223.

- ↑ Watson, pp. 223-24.

- ↑ Watson, pp. 223-224.

- ^ Creighton, p. 122.

- ↑ Innis, (Bias) p. 139.

- ↑ Member History: Harold A. Innis. American Philosophical Society, accessed October 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Watson, pp. 224-25. see also Creighton, pp. 136-40.

- ↑ Watson, pp. 250-55.

- ^ Foreword by H. Marshall McLuhan in Havelock, p. 10. see also Watson, p. 405.

- ↑ Heyer, p. 61.

- ↑ Innis: Empire , p. 7.

- ^ Marshall McLuhan: Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man . Corte Madera, California: Gingko Press, 2003

- ↑ James W. Carey: "Harold Adams Innis and Marshall McLuhan" in McLuhan Pro and Con , Pelican Books, Baltimore, 1969, p. 281.

- ↑ Patterson, pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Watson, pp. 410-11.

- ^ Marshall McLuhan: Marshall McLuhan Unbound. Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, v.8, 2005, pp. 5-8.

- ^ Carey: McLuhan Pro and Con , p. 271.

- ↑ first: Harold A. Innis. A memoir. Preface by H. Marshall McLuhan. Harold Innis Foundation, Toronto 1982 ISBN 9780969121213

- ↑ George Grant, 1918–1988, Canadian philosopher

- ↑ Neill: see also web links

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Innis, Harold Adams |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Innis, Harold |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Canadian economist and author, professor of political economy |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 5, 1894 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Otterville , Ontario |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 8, 1952 |

| Place of death | Toronto , Ontario |