Wendell Willkie

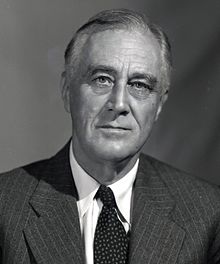

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born February 18, 1892 in Elwood , Madison County , Indiana , † October 8, 1944 in New York City ) was an American lawyer and businessman who was politically active. In the 1940 presidential election , he was the Republican candidate for incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt .

Willkie was a trained lawyer and worked as a business lawyer after completing his studies and military service. From the late 1920s, he rose to leadership positions. Politically, he was initially involved with the Democrats , but then switched to the Republicans. As managing director of the Southern Company , he turned against the nationalization of projects of his company, which was operated by the democratic Roosevelt government. Known as a charismatic speaker, leading Liberal Republicans saw in him a possible presidential candidate for the 1940 election. Surprisingly, Willkie actually won the Republican nomination. The decisive factor here, under the impression of the Second World War that had broken out in Europe, was his advocacy of an internationalist foreign policy . During the election campaign, he also spoke out in favor of keeping the New Deal , but wanted to make Roosevelt's reforms more efficient and less bureaucratic. Although his performances sparked enthusiasm, in the end President Roosevelt triumphed and was thus elected for a third term. After his defeat, Willkie was loyal to the president, who entrusted him with a number of diplomatic missions during the war. Willkie also got involved in political and social projects. In 1941 he was a co-founder of Freedom House , he also took a strong stand against racial discrimination . In the run-up to the 1944 presidential election , his attempt to be nominated again as his party's candidate failed. In October 1944, Willkie died of a heart attack at the age of 52 .

Both for his political commitment and for his election campaign, which many regarded as remarkably fair, in times of a foreign policy crisis, Willkie was highly valued by all parties. His stance, which opposed isolationism and thus the possible holding out of the USA in Europe threatened by the National Socialists , enabled the United States to enter World War II politically in 1941 and thus to significantly influence the war in favor of the Allies .

Life

First years of life and training

Wendell Willkie was born to parents of German origin on February 18, 1892 in Elwood , Indiana . Willkie had a sister and four other brothers. His grandparents and his father emigrated from Aschersleben in Germany to the USA in 1858. His parents both worked as lawyers in a joint law firm. His mother was the first woman in the state of Indiana to be officially admitted to the bar. The Willkie family did not belong to the upper class of society and had no outstanding fortunes, but the parents of the family were able to secure a middle-class livelihood. After attending school, Wendell began studying. In 1913 he graduated from the University of Indiana the Bachelor of Arts . He completed this course with a grade point average in the upper midfield. After that he was part of the Beta Theta Phi student fraternity , where he taught history for a year .

Wendell already showed political interest in his youth. His grandfather took part in the revolutionary uprisings in Europe in 1848/49, which aimed at overcoming the principalities towards a more modern and democratic political and social order. Tales from the family impressed Wendell despite the unsuccessful surveys in Europe and strengthened his interest in the democratic process. Although his parents had no political ambitions, they were supporters of the Democratic Party . As a child, Wendell attended several campaign events for Democratic candidates. The (three times unsuccessful) presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan made a great impression on him . He followed the presidential election of 1912 with great attention. He was particularly enthusiastic about the Democratic candidate and later election winner Woodrow Wilson . As Willkie biographer Steve Neal reflected, Wilson was the man Willkie "most admired" at the time. Willkie saw himself as a staunch supporter of progressivism , who advocated progress- oriented politics and stood for a balance between economic and social issues ( e.g. anti- trust legislation or better working conditions for workers in the mining industry ). For a time he also dealt with the theses of socialism and communism ; for example by reading Karl Marx 's Das Kapital .

Since Willkie's activity as a history teacher was paid comparatively low wages, his brother Fred offered him a job as a laboratory technician in Puerto Rico . Wendell accepted the offer in November 1914 and settled with his brother, who was temporarily living on the island. Wendell was not particularly comfortable in Puerto Rico. He was especially touched by the poverty of the locals. Gardner Cowles, Willkie's boyfriend at the time, stated in an interview conducted decades later: “From then on, Wendell said that he was determined to work for better balance and social awareness. If he ever got into an influential position, he wanted to give it a different look ”. In autumn 1915, also feeling homesick , Willkie decided to return home. His main goal now was to study law. Upon returning home, Willkie completed a law degree at the Indiana School of Law , which he successfully completed in 1916 with a Bachelor of Laws . After that he worked for a while in his parents' office.

As a young man, Willkie closely followed the political world situation after the First World War broke out in Europe in 1914 . Here he was completely on the line of President Woodrow Wilson, who held on to American neutrality for almost three years. However, after the US entered the war at Wilson's instigation in April 1917, Willkie supported the government's course. From there on he described himself as a Wilsonian , that is, as a proponent of an active foreign policy that was primarily intended to promote the spread of democracy and a market economy . A few days after the American declaration of war on the Central Powers , he voluntarily joined the US Army and was appointed first lieutenant a little later . Originally christened Lewis Wendell Willkie by his parents, an armed forces administrator swapped his two first names and he was known as Wendell Lewis Willkie. Willkie himself was not bothered by it, as friends had previously addressed him as Wendell. He therefore made no attempt to correct the mistake. He signed documents with the name Wendell L. Willkie. Willkie stayed in the United States for more than a year, where he was stationed in various army training camps. It was not until the fall of 1918 that he was sent to the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe. But when Willkie arrived in France , the war had already been won for the Allies and he was no longer able to take an active part in the fighting. Nonetheless, he stayed in Paris for a few months , serving as an assistant to US prosecutors involved in the prosecution of war crimes .

Professional career and political activities

Upon his return to the United States, Willkie retired from the armed forces and married Edith Wilk in 1919; The marriage resulted in their son Philip, born in 1924, who also embarked on a legal career and was politically active. Since the 1930s, Willkie also had an extramarital relationship with the author and journalist Irita Van Doren, who also advised him politically.

Professionally, he started work as a lawyer again and was legal adviser (corporate lawyer) the company Firestone Tire and Rubber Company . For this position he relocated from Indiana to Akron in the neighboring state of Ohio . Through his ambition he earned the respect of his superiors in the years that followed and was soon considered to be a man with a bigger future as a lawyer. In 1929 Willkie left Firestone, Tire & Rubber and became a legal advisor to the Southern Company (C&S), a company that focused on the energy supply of eleven US states. Although the change was not easy for him personally, he saw it as necessary to give his career a new boost; His career prospects were limited in a city like Akron. Willkie and his family moved to New York City for his new job . Although the way of life in the metropolis was alien to him at first, he soon saw numerous advantages in big city life.

Since his return from Europe, Willkie was politically active in the Democratic Party , where he was part of the liberal party wing. Even in Akron, Ohio, the aspiring lawyer was one of the city's most prominent Democrats. In election campaigns, he campaigned for James M. Cox , then governor of the state and Democratic presidential candidate from 1920 . Also in 1920 there were votes in the local party executive that brought Willkie's candidacy for the US House of Representatives into play. Willkie thought seriously about this possibility, ultimately decided against it after careful consideration, as the risk of defeat in this more Republican constituency was too high for him. Together with a number of like-minded party comrades Willkie fought against the political influence of the racist Ku Klux Klan , whose worldview he categorically rejected. At the Democratic National Convention of 1924, the nominating convention for the upcoming presidential election this year, he served as a delegate. Eight years later, in the run-up to the 1932 presidential election , he was a delegate at the Democratic nomination convention. Originally Willkie supported the candidacy of the hopeless Senator Newton D. Baker , later he voted for the New York governor Franklin D. Roosevelt , who was then also elected. During the election campaign in the autumn of 1932 he actively supported Roosevelt's election campaign, including through donations. Like a majority of Americans, Willkie believed that Roosevelt was more likely than Republican incumbent Herbert Hoover to overcome the Great Depression , which the country had suffered since the stock market crash of 1929 . In a clear decision, Roosevelt finally prevailed.

Professional and political advancement

In January 1933, Willkie was promoted to President of C&S. At 41, he was the youngest president of a major energy company; hence his rise found reception in the national press. After his promotion, Willkie faced major challenges. The Great Depression also ran into economic difficulties for C&S .

After Roosevelt finally became president in 1933, he pursued an economic and social policy known as the New Deal . A number of programs and initiatives resulting from this reform, the regulation of the financial markets and the introduction of social security , met Willkies' approval. Among other things, Roosevelt founded the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which was supposed to supply the completely backward Tennessee Valley with cheap energy and protect it from flooding. The Authority was a direct competitor to C&S. Willkie was the opponent of the TVA, he spoke out against the participation of the government in economic life, although he saw himself as an advocate of a state-regulated market . He was convinced that active participation by the state would damage competition to such an extent that innovations would only be possible to a limited extent. In addition, state-owned companies would be less tied to profitability , as they would theoretically be able to generate unlimited losses at the expense of public budgets. In 1933, Willkie succeeded in getting the US Senate to prohibit the TVA from building overhead lines. Roosevelt voted the Senate one more time; a newly passed law gave the TVA extensive powers. She received practically unlimited credit from the state treasury at low interest rates and was able to buy C&S in 1939. Willkie left the party that same year and joined the Republicans.

By now, Willkie had become a well-known figure in public life through his criticism of the TVA. He increasingly sought contact with the press; The lawyer maintained a good relationship with many journalists, to which his perceived personality also contributed. On January 6, 1938, he was a guest on a national radio talk show, where he fought a political duel with the Democrat Robert H. Jackson . Jackson was a senior Justice Department official in the Roosevelt administration at the time and was seen as his party's potential presidential candidate for the 1940 election. After the show ended, most of the audience and reporters were of the opinion that Willkie had won the speech duel. Liberal Republicans began to see the perceived charismatic lawyer as a potential presidential candidate for 1940.

1940 presidential election

The way to the candidacy

The political climate in the United States had changed by the beginning of the 1940 election year in such a way that the public focus was more on foreign policy. This was essentially due to the aggressive policies of the German Empire and the Japanese Empire. In the past two years there had been no major reform announcements from the Roosevelt administration. The adoption of the New Deal programs was essentially complete. Although the reforms stabilized the economy considerably and alleviated humanitarian hardship, there had been no significant upswing that would finally lift the country out of the Great Depression.

Foreign policy developments made it increasingly likely that President Roosevelt would run for a third term. Although there was resistance to such plans within the party, especially from the conservative southern states , the incumbent was still very popular with the party base and the population. The Republican Party, meanwhile, was deeply divided. Domestically, a conservative and a liberal-moderate wing of the party faced each other. The Conservatives called for a return to laissez-faire politics, as in the 1920s under Presidents Harding , Coolidge and Hoover, and a revision of the New Deal. The liberal wing, which included Willkie and the 1936 candidate Alf Landon , advocated maintaining many New Deal programs, but wanted to make them more efficient. Republicans were also split into two camps on foreign policy issues. The majority of the party’s leaders belonged to the isolationists, who wanted to keep the US’s foreign policy engagement to an absolute minimum. They rejected demands from the British under Prime Minister Winston Churchill to provide military support to the United Kingdom in its war against the Nazi regime, for example in the form of supplies of equipment and weapons. A number of Republicans even called for negotiations to be opened with the Third Reich. President Roosevelt categorically rejected this, but he too hesitated before the elections with extensive support for the British, knowing that there was still a predominantly isolationist mood among the American population. Because of this mood, Willkie, who, like the president, saw himself as an internationalist, that is, advocated a more active engagement of the USA in the world, was given few chances for the Republican top candidacy. In addition, his liberal views on economic and social policy issues met fierce resistance from the conservative wing of the party. Many conservative Republicans were also bothered by Willkie's past as a Democrat. The arch-conservative Senator Robert A. Taft , Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg and the politically moderate New York District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey were considered favorites for the Republican nomination, all of whom called for isolationist foreign policies of varying degrees.

Public opinion gradually began to turn after Adolf Hitler began to invade a number of neighboring European countries in the spring of 1940 (Poland had been invaded as early as 1939). In particular, the rapid military defeat of France and the ensuing capture of Paris by the Wehrmacht in June 1940 triggered a shock in the US public. As a result of these events, Willkie's popular vote began to grow rapidly. Liberal Republicans also believed the charismatic Willkie, who was also known as a good speaker, to be the most likely to win an election.

The Republican Nominations Congress

When the Republican nomination convention began in June 1940, Taft, Vandenberg or Dewey were the winners of the vote. Dewey had won a number of primary elections, but in 1940 the overwhelming majority of delegates were elected not by primary elections but by the local party executive committee. In any case, only a small number of states held such primaries; therefore there was also the possibility for Willkie to be nominated, although he only achieved around three percent of the votes in the primaries. After many political observers saw a threat to the United States as a result of the National Socialists' victory over France, Dewey's approval fell quickly, as at 38 he was seen as too inexperienced to lead the country in such times of crisis. Meanwhile, public approval of Willkie continued to grow, and the party congress received thousands of telegrams from citizens who spoke out in favor of Willkie. At the gathering, his supporters made themselves heard with chants as they repeatedly chanted “We want Willkie!”. In the first ballot, Dewey was ahead, but the young prosecutor clearly missed the necessary absolute majority . Willkie did surprisingly well in third behind Dewey and Taft. In the third ballot he finally overtook Taft in the number of delegates, in the fourth round he also left Dewey behind, but it was not enough to achieve an absolute majority. Dewey's supporters, who also belonged to the liberal wing, now defected Willkie, who finally managed to defeat Taft in the sixth ballot. He became a candidate for a major party for the presidential election without ever having held any political office. Until Donald Trump was nominated in 2016 , he was the only candidate from a major party who had previously neither held a political mandate nor a high military rank. After his nomination, Willkie did not select his candidate for the vice presidency himself, but left the selection to the delegates. The convention chose Charles L. McNary , a Senator from Oregon . McNary represented moderate positions domestically and appeared to be a useful addition to Willkie, both through his political experience and geographically.

Although Willkie's defeated opponents were officially loyal, there was also criticism within the party. Above all, the still influential wing of the Isolationists was skeptical of the candidate. Former Republican President Herbert Hoover (1929-1933), who in 1940 also figured out chances of being nominated as a surprise candidate, was not very convinced of Willkie. Even a face-to-face meeting of the two in the summer of that year did not change anything. Hoover considered Willkie to be too liberal, whose convictions both domestically and internationally were more like Roosevelt's than his own. Willkie, meanwhile, saw Hoover as a representative of outdated politics. On the other hand, Willkie was widely supported by Liberal Republicans; So the 1936 presidential candidate Alf Landon got involved with him.

Willkie's election campaign

While Willkie surprisingly emerged as the winner of the Republican nomination, the Democrats nominated incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt for a third term by a large majority . Due to the tense foreign policy situation, the President had decided to break with tradition and run for the White House a third time. There was occasional criticism of Roosevelt's plans from within the party, especially from the conservative wing of the southern party (Vice President John Nance Garner fell out with Roosevelt), but the president remained extremely popular with the party base and the population. Many leading democrats, such as Interior Minister Harold Ickes , believed that only the charismatic Roosevelt could overcome the charismatic will in the election.

Willkie concentrated his election campaign on three major topics: the supposed inefficiency of the New Deal, what he saw as a lack of preparation for an impending war and Roosevelt's attempt to be elected for a third term. Like the majority of the US population, Willkie was not hostile to the New Deal as a whole. Willkie advocated numerous reforms such as the introduction of social security, the creation of the separate banking system and further regulations of the financial markets as well as a statutory minimum wage . For him, there was no doubt that the almost completely deregulated economy of the 1920s was primarily responsible for the collapse of the stock exchange and the accompanying global economic crisis . Willkie also understood that the humanitarian hardship resulting from the Great Depression, where it was not fought, as in large parts of Europe, formed an ideal breeding ground for totalitarian and fascist regimes such as in the German Reich or Japan. He therefore announced that in the event of an election victory, he would keep a large part of the New Deal, but make many of the programs more efficient and less bureaucratic. For Willkie, the supposed bureaucracy of the New Deal was partly responsible for the lack of a larger and more sustainable economic upswing, although the economic and humanitarian situation has noticeably improved since Roosevelt took office (in fact, a major upswing did not begin until the Second World War). Willkie also said he would work more closely with business as president to finally end the economic depression.

In terms of foreign policy, there were relatively few differences between the two candidates. Both refused to talk to the Nazi leadership and declared their solidarity with the British and French. However, Willkie accused the president of not preparing the country adequately against an impending war. Although Roosevelt actually a slow since 1938 upgrade began, he found himself not least by Willkie's criticism forced a month before the election, the reintroduction of in October 1940, compulsory military service to be arranged. Willkie was initially positive about this decision, but then backtracked a little after the majority of the public reacted negatively to this move by the White House. Both candidates and the majority of the population still refused to participate directly in the war.

Willkie expressed harsh criticism of Roosevelt's efforts after a third term. Through his liberal positions, he hoped to be able to win over democrats and other liberal currents who refused a third term for the president. Although the 22nd amendment to the constitution, which restricts the eligibility of each president to two terms, did not come into force until 1951, no president had ruled for more than two terms. This tradition goes back to the first President George Washington , who recommended all successors not to serve longer than two terms in office. In opposition to Roosevelt, a series of campaigns in support of Willkie's candidacy were formed. Even some Democrats joined the under the slogan “No third term! Democrats for Willkie ”(“ No third term! Democrats for Willkie ”).

Although Willkie competed against a still popular incumbent, he was able to inspire the masses with his performances. Willkie was known not only as a charismatic but also as a gifted public speaker. His election campaign events were always well attended. Willkie biographer Steve Neal wrote that Willkie was able to arouse such enthusiasm at his performances as no Republican candidate since Theodore Roosevelt has done. Like his opponent, Willkie recognized the importance of broadcasting, where he addressed the public directly in commercials. Republican National Committee chairman Joseph William Martin later wrote that Willkie wanted to buy so much airtime on the radio that the party spent all campaign money (including those earmarked for the 1942 congressional elections). In September 1940 he received an official declaration of support from the renowned daily newspaper The New York Times , which is known as a liberal medium. This was remarkable in that she otherwise supported mostly democratic candidates. Willkie was the only one of Roosevelt's four Republican opponents for whom this newspaper issued an election recommendation. In both 1932 and 1936, and again in 1944, the Times endorsed Franklin D. Roosevelt.

However, by American standards, the election campaign had been remarkably fair on both sides. Both candidates showed respect for their opponent and let out personal attacks on the other.

Election day

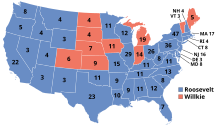

Roosevelt was able to lead all polls during the election campaign in the fall of 1940 with varying distances. On election day, November 5, 1940, President Roosevelt ultimately won with 54.7 against 44.8% of the vote and was the only US President elected for a third term. Of the 48 states at the time, the Republican duo of Willkie and McNary won a majority in ten, primarily in the Midwest as well as Maine and Vermont , while Roosevelt secured a majority in 38 states. The incumbent clearly prevailed in the electoral committee with a ratio of 449 to 82 votes. Willkie received a total of 22.3 million votes, and 27.3 million voters voted for his opponent. Despite his defeat, Willkie was able to win six million votes more than his party colleague Alf Landon in 1936 , Roosevelt's votes remained almost the same in total. Still, Willkie received more votes in absolute terms than any Republican candidate before him. Only Dwight D. Eisenhower was able to overtake this in the 1952 election .

Willkie accepted his defeat with humility and promised to support the president primarily in foreign affairs. After the election, Roosevelt still showed his adversary respect. A few days after his victory, the President said privately to his son James : "I'm happy I've won, but I'm sorry Wendell lost" ("I'm happy to have won, but I'm sorry that Wendell lost" ).

Later years

Further political and professional work

After his defeat, Willkie remained a well-known public figure in the United States. His support in parts of the population was still great and he was by no means politically written off at the age of 48. In the months following the election, he received more than 100,000 letters from citizens expressing their support. For his party colleague, the 1936 candidate Alf Landon, there were only 6,000. Willkie regretted not being able to answer all messages personally due to the high number of supporters.

In the following years he showed himself to be loyal to the president again and supported him in a number of issues; the former presidential candidate strongly endorsed the passage of the lending and leasing law in the spring of 1941. Roosevelt now saw in his former opponent an important ally for the implementation of his foreign policy goals. Shortly after the election, Roosevelt's adviser Felix Frankfurter recommended that the President send Willkie on a political visit to Great Britain to signal non-partisan support for the ally. In the spring of 1941, Willkie undertook a diplomatic trip to Great Britain on behalf of the President, where he met for talks with Prime Minister Winston Churchill . Although both were united in their opposition to the Third Reich, Willkie saw the British head of government as too conservative to participate in a post-war order and criticized British colonialism . Here Willkie was entirely on the line of Roosevelt, who also rejected British colonialism and advocated the right of peoples to self-determination. Nevertheless, the British and Americans remained closely allied in their endeavors to overthrow the Nazi regime. Churchill wrote of the conversation with his American visitor that it was “a long talk with this most able and forceful man”. Among other things, the former presidential candidate visited the cities of Manchester , Liverpool and Birmingham that were hit by German bombs during his trip . Pictures of Willkie while walking through streets in London that were destroyed by German bombs went through British and American media. In the spring of 1941 Willkie also conducted political talks on behalf of Roosevelt with the Irish Prime Minister Éamon de Valera , whom he convinced to give up neutrality during World War II. After his return to the United States, Willkie faced a hearing in the United States Senate , where, under the influence of the London visit, he campaigned for the passage of the Lending and Lease Act. By referring to Willkie's statements, President Roosevelt tried to convince politicians and the population of the lending and leasing law by presenting the matter as a non-partisan one. However, there were still reservations, especially within the conservative wing of the party. Charles Lindbergh also spoke out against the plan at a Senate hearing. Nevertheless, the law was passed in March 1941. A poll published in the spring of 1941 showed that 60% of US citizens thought Willkie would have been a good president.

In April 1941, Willkie also resumed his professional career and became a partner in a New York law firm which, after joining, was renamed Willkie, Owen, Otis, Farr, and Gallagher . Two months later he represented a number of film producers before Congress who were accused of producing propaganda material in support of a possible US entry into the war. Willkie defended the filmmakers' right to express their views, noting: "The rights of the individuals have become meaningless when freedom of expression and press are destroyed" ("The rights of the individuals mean nothing if freedom of speech and freedom of the press are destroyed." "). The Congress then refrained from further action against the producers. Willkie became a popular figure in Hollywood as a result . His charismatic appearance met with a certain approval, so that he was invited to host the 1942 Academy Awards .

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the resulting entry into the war by the US , Willkie expressed his full support for his former rival, President Roosevelt, in the global war against fascism . Willkie was open to taking on a role as coordinator of war production. Roosevelt offered this post to businessman Donald M. Nelson . Labor Secretary Frances Perkins suggested appointing the former presidential candidate as chief mediator between the civil and defense industries. Willkie turned down this offer after White House staff passed the idea on to the press at an early stage. Also at the beginning of the year, Willkie considered running for governor of New York in the upcoming fall election. A number of Republican politicians in New York were in favor of such a candidacy, and Roosevelt himself, who had held the post before his election as president, toyed with the idea of helping his former rival. Ultimately, Willkie abandoned the venture because he had come to the conclusion that he could not win the Republican primary against Thomas E. Dewey . The up-and-coming public prosecutor, who surprisingly only narrowly lost the election in 1938, was considerably better networked with both the party base and the functionaries than Willkie, a political lateral entrant, who had also made himself unpopular in parts of his party through his close cooperation with Roosevelt. Above all, Willkie feared that a defeat in the free choice for the Republican candidate could jeopardize his future ambitions for the presidency.

In the summer of 1942, Willkie again undertook a political world tour on behalf of Roosevelt, which took him to North Africa, the Middle East , the USSR and China . As personal representative of the President was Willkie his mission's aim is "to demonstrate American unit to collect information and the plans for those with important heads of state post-war period to discuss" ( "demonstrating American unity, gathering information, and discussing with key heads of state plan for the postwar future "). In Morocco he held talks with the British commander, Bernard Montgomery . In Jerusalem , the former presidential candidate met with representatives of the Jewish and Arab communities and suggested that both sections of the population should be represented in the government in order to prevent conflicts. Willkie later described the tensions there as extremely complicated and expressed his assessment that, in his opinion, the conflicts could not be resolved through “goodwill and decency” alone. After a meeting with the Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, Willkie campaigned for more extensive support for the Soviet Union under the lending and leasing law to defend against the German Reich. This happened particularly under the impression of the German invasion of the USSR the year before ( Operation Barbarossa ). During his talks in China, he assured Chiang Kai-shek of American aid against the Empire of Japan and publicly spoke out again clearly against colonialism, which was particularly a topic in the British media and was criticized by Churchill. Upon returning to the United States, Willkie wrote his best-known book, One World , which appeared in April 1943. In it, as a consequence of two world wars, he spoke out in favor of the formation of an international organization in the form of the UN (founded in 1945) , which should primarily be used as a forum for worldwide conflict resolution between states. This finally made him one of the leading internationalists in the USA.

Social Commitment

In 1941, Willkie and Roosevelt's wife Eleanor co-founded Freedom House , an international non-governmental organization (NGO) headquartered in Washington, DC, whose goal is to promote liberal democracies worldwide. Today she is best known for her annual reports Freedom in the World and Freedom of the Press .

In the years following his presidential candidacy, in particular, he repeatedly spoke out on socio-political issues; so Willkie took a clear stand against racial discrimination . Also called for the full integration of blacks in the US armed forces . He refused to divide the battalions by skin color. On the issue of equality, he accused both parties of a lack of commitment. Willkie took the view that it was absurd to fight the ideology of anti-Semitism and racism in World War II and at the same time to restrict the social and economic rights of African Americans in one's own country . During 1942 and 1943 he also campaigned in Hollywood for better working conditions and fair treatment of African Americans in the film industry. During the 1944 election campaign, he openly called for cabinet posts and high judicial posts to be filled with blacks. His attitude to civil rights brought Willkie as early as 1940 the advocacy of prominent black people such as boxer Joe Louis and various African American newspapers. Although Willkie was reluctant to publicly criticize the internment of Americans of Japanese descent ordered by Roosevelt during World War II, he said in a speech that there was no justification for curtailing citizens of their rights.

Shortly after Willkie's death, Eleanor Roosevelt reflected on his commitment to equality for African Americans in her My Day column :

“Mr. Willkie placed great emphasis on the need we have in this country to be just to all of our citizens, because without equality there can be no democracy. His outspoken opinions on race relations were among his great contributions to the thinking of the world. I thought of that last night when I attended a "register and vote" rally in Harlem. In that great crowd of people, when his name was mentioned, it was quite evident that he was held in great respect and affection. "

"Mr. Willkie particularly emphasized the need for us in this country to be fair to all of our citizens, because without equality there can be no democracy. His expressed opinions on racial relations were among his great contributions to his understanding of the world. This is what I thought of at the “register and vote” rally last night in Harlem . When his name was mentioned in this great crowd it was obvious that he would be remembered with great respect and affection ”

Willkie also appeared in court as an advocate of civil rights: in November 1942 he defended William Schneiderman before the Supreme Court of the United States . Schneiderman, then the leader of the Communist Party in California , had been stripped of his citizenship by the government on the grounds that he had withheld his membership of the Communist Party when he was naturalized . That case was politically extremely sensitive for Willkie, but this justified his commitment in a letter to a friend: “I am sure that I am right to represent Schneiderman. If it is time to defend civil liberties, then now “(" I am sure I am right in representing Schneiderman. Of all the times when civil liberties should be defended, it is now. "). In the end, the Supreme Court upheld the lawsuit and Schneiderman's citizenship had to be restored.

1944 presidential election

Throughout 1943, Willkie began preparing for another presidential run for the fall of 1944. He toured the country, giving speeches to Republican groups, and fundraising. Although there were still great reservations within his party against the political career changer, especially because of differences in domestic politics and his proximity to Roosevelt, many high-ranking Republican politicians were aware of Willkie's popularity. For the 1942 congressional elections, many high-ranking officials wanted the former presidential candidate to support them in the election campaign, but the latter refused because of his trips abroad. Still, Willkie was considered one of the favorites for Republican candidacy alongside General Douglas MacArthur in the summer and fall of 1943 . During his election campaign in autumn 1943 and in the first months of 1944 Willkie again spoke out in favor of an internationalist foreign policy and warned against a relapse into isolationism. Domestically, too, he remained true to his line, which paradoxically also met with some approval among the progressive wing of the Democrats. So Willkie urged his party to accept large parts of the New Deal . He also reaffirmed his support for more civil rights and announced in the event of his election as president that he would like to fill high government posts with African Americans.

As was the case four years earlier, only a small number of party congress delegates were awarded in primaries in 1944 , which were only held in a few states. Although participation in the primary election was not mandatory for the presidential candidacy, these polls were seen as a kind of mood test. Willkie won the Primary in New Hampshire on March 14th, albeit with a significantly smaller lead than expected. He had previously campaigned significantly more than his peers in this New England state . A majority of the local newspapers also spoke out in favor of him (so-called endorsement ). His rivals were General MacArthur, the more liberal New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey , his fellow governor from Ohio John W. Bricker , representative of the conservative party wing, and the former governor of Minnesota Harold Stassen , who was rather moderate. A good two weeks later, Willkie decided to take part in the Wisconsin primary and, in the light of the New Hampshire result, stated that if he did poorly, he would give up his candidacy. This was a delicate undertaking because isolationists in Wisconsin still had a comparatively strong position within the party. In addition, the Republican electorate in this Midwestern state consisted largely of German-Americans , who were already skeptical of Willkie. In the two weeks leading up to the election, Willkie traveled across the States and gave numerous campaign speeches, which was made difficult for him by the inclement weather like a blizzard . Nevertheless, Willkie managed to attract a large audience of several thousand people with his speeches, which were perceived as charismatic. His main opponent Dewey, however, focused on a high presence on the radio and numerous leaflets that he had distributed in the state. Willkie then clearly lost the primary on April 4, 1944, without having won a delegate for the party congress. Dewey secured 17 of the 24 delegates to be awarded, four went to MacArthur and another three to Stassen.

After his clear defeat in Wisconsin, Willkie announced his withdrawal from the electoral process. Speaking to supporters, he stated:

“I quite deliberately entered the Wisconsin primary to test whether the Republican voters of that state would support me… It is obvious now that I cannot be nominated. I therefore am asking my friends to desist from any activity toward that end and not to present my name at the convention. I earnestly hope that the Republican convention will nominate a candidate and write a platform that really represents the views which I have advocated and which I believe are shared by millions of Americans. I shall continue to work for these principles and policies for which I have fought during the last five years. "

"I went into the Wisconsin primary with awareness to see if the Republican voters would support me ... It is now evident that I cannot be nominated. Therefore I ask my friends to stop their activities and that my name does not appear on the ballot paper for the party conference. I sincerely hope the Republican Congress will nominate a candidate and write a manifesto that reflects my views, which I stand for and which I believe are shared by millions of Americans. I will continue to work for these principles and policies that I have fought for for the past five years. "

Last months and death

After dropping out of the presidential race, Willkie said he wanted to go back to work as a lawyer. Private friends of the lawyer doubted that he wanted to stay out of the political business for longer. President Roosevelt, who was running for a fourth term at the end of the war, also continued to appreciate his former challenger. According to Willkie biographer Steve Neal, the president was keen to bring Willkie back to the Democratic Party. Roosevelt is said to have even toyed with the idea of offering him the vice-presidential candidacy at his side for the 1944 election. But Willkie remained skeptical of the Democrats and had doubts whether he would be welcome there or even politically enforceable as Roosevelt's running mate ( Harry S. Truman later received this candidacy ).

Back in New York in the summer of 1944, Willkie helped build the Liberal Party of New York , a social liberal party whose long-term goal was national significance, in order to give both liberal and progressive members of the Democrats and Republicans a new political home. President Roosevelt, who himself had to fight within the party with the conservative wing of the Democrats from the south , followed this with great interest. But when the plans for this new party came to the public early through a leak in the White House, Willkie distanced himself from Roosevelt, who he accused of abusing him for his political purposes. Although the Liberal Party never entered the national stage in the USA, it still exists in New York State as a small party today and often supports the Democrats in national elections such as those for governor. Later, the Conservative Party of New York was formed as a counterpart in opposition to the liberal (republican) governor Nelson Rockefeller in the 1960s. After the leak, Roosevelt apologized in a personal letter to Willkie. Shortly thereafter, the President began to consider proposing Willkie as the first Secretary-General of the United Nations to assist in the preparations for the foundation.

Within the Republican party leadership, Willkie had made himself increasingly unpopular through his cooperation with Roosevelt and his domestic and foreign political convictions, although he still received some support from the party base. At the nomination party convention in the summer of 1944, at which Dewey was elected as a candidate, he was not scheduled to speak, whereupon he completely canceled his participation. Willkie nonetheless remained present in the media and wrote a number of opinion pieces in the newspapers. In it he reaffirmed his advocacy of active foreign policy and civil rights for African Americans. In the election campaign, however, he spoke out neither for Roosevelt nor for Dewey. However, both hoped for a public election recommendation. For a short time, Willkie also considered working as a newspaper editor.

In August 1944 he suffered a first heart attack while on a train journey and did not see a doctor until his wife was persuaded. However, he refused hospital treatment. Due to the heavy consumption of whiskey and cigars, his health had not been the best in the past few years. Another heart attack occurred in September 1944. After several more heart attacks in early October, Wendell Willkie died on the morning of October 8, 1944 at the age of 52. After his death, numerous media published obituaries; President Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor recognized Willkie for his life's work. During his laying out in New York's Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, around 100,000 people paid their last respects to the deceased. Roosevelt's Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson offered Willkie's widow Edith a burial in the Arlington National Cemetery , but this refused. Willkie was then buried in his home in Indiana.

His running mate from 1940, Charles McNary , had also died in February 1944. It was the only time in American history that both presidential and vice-presidential candidates for a major party died during the term they ran for.

Aftermath

Already after Willkie's nomination for the Republican presidential candidate, President Roosevelt described him as "God sent", as there would be no argument about the question of support for the United Kingdom in the election campaign. In order to be able to operate successfully on an international level, it was of central importance for Roosevelt that his country should not be divided by an election campaign and thus his position weakened. The writer Walter Lippmann also saw Willkie's nomination as decisive. With one of the other candidates available in 1940, Lippmann said, the Republican Party would have fatally turned its back on all those who opposed Adolf Hitler. Historian Charles Peters wrote in the early twenty-first century: “It is fair to say that Willkie's impact on the United States and the world can be seen as greater than that of many men who actually held office [as president]. During a critical moment in history, he stood for the right things at the right time ”. Willkie's support for the president in wartime was repeatedly discussed in public in the US history that followed. In 2004, Democratic Senator called Zell Miller of Georgia on Willkie, as it relates to the Republican Party for the re-election of Republican President George W. Bush spoke. Miller justified his advocacy for Bush with the Iraq war . Unlike the candidate for the Democrats, John Kerry , Willkie had his back on his president and not criticized him for his war policy and thus weakened the position of the head of state. Representatives of the Democratic Party rejected this comparison at the time.

The writer Samuel Zipp reflected on Willkie's political work and stated that his travels on behalf of Roosevelt during the Second World War and his book One World had increased public approval of an active foreign policy of the USA and thus an important contribution in the fight against the Nazi regime and the shaping of the post-war world. It can also be seen that Willkie's foreign policy beliefs had a long-term influence on the supporters of the Republican Party. For example, the future US President Gerald Ford admitted decades later that Willkie had turned him from an isolationist into an internationalist. He also wrote: “He launched the most successful and unprecedented challenge to conventional nationalism in modern American history ... He urged Americans to imagine a new form of connection with the world, one to which millions of Americans responded with unprecedented urgency. "

Willkie biographer Steve Neal wrote of the presidential candidate's historical classification:

“Though he never became President, he had something much more important, a lasting place in American history. Along with Henry Clay, William Jennings Bryan, and Hubert Humphrey, he was the also-ran who would be long remembered. 'He was a born leader,' wrote historian Allan Nevins, 'and he stepped to leadership at just the moment when the world needed him.' Shortly before his death, Willkie told a friend, 'If I could write my own epitaph and if I had to choose between saying, “Here lies an unimportant President”, or, “Here lies one who contributed to saving freedom at a moment of great peril ", I would prefer the latter. '"

“Although he never became president, he gained something more important, which was a permanent place in American history. Along with Henry Clay , William Jennings Bryan and Hubert H. Humphrey , he was one of the candidates who would long be remembered. 'He was a born leader,' wrote historian Alan Nevins, 'and he took the lead exactly when the world needed him'. Shortly before his death, Willkie said to a friend, 'If I could inscribe my own tombstone and have a choice between' Here lies an insignificant president 'or' Here lies someone who helped save freedom at a time of great peril ' , I would prefer the latter. '"

During the 2016 US presidential election campaign , the media drew a few parallels between Wendell Willkie and the Republican candidate and later President Donald Trump . After Willkie, Trump was the first candidate from a major party to have held neither political office nor high military rank prior to his nomination. Another thing they had in common was their background as a "rich New York businessman" and the fact that both had been members of the Democratic Party for a while.

Cultural reception

In the novel The Golden Age by Gore Vidal , one of the focal points is the rise of Wendell Willkie to the Republican candidate in the 1940 presidential election.

Works

- This Is Wendell Willkie . 1940 (speeches and essays)

- One World . 1943

- An American Program . 1944

Literature (selection)

- Susan Dunn: 1940: FDR, Willkie, Lindbergh, Hitler — the Election Amid the Storm. Yale University Press, New Haven 2013.

- Ellsworth Barnard: Wendell Willkie, fighter for freedom . 1966

- Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . 1989

- Herbert S. Parmet and Marie B. Hecht: Never Again: A President Runs for a Third Term . 1968

- Charles Peters: Five Days in Philadelphia: The Amazing "We Want Wilkie!" Convention of 1940 and How It Freed FDR to Save the Western World . Public Affairs, New York 2006

- Samuel Zipp: When Wendell Willkie Went Visiting: Between Interdependency and Exceptionalism in the Public Feeling for One World American Literary History, Volume 26 , 2014

Web links

- Newspaper article about Wendell Willkie in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Wendell Willkie in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- Wendell Willkie in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Remarks

- ↑ GERMANY: Willke, Willcke, Willeke. In: time.com. March 24, 1941, accessed December 30, 2014 .

- ↑ Ellsworth Barnard: Wendell Willkie, Fighter for Freedom. University of Massachusetts Press, 1966, ISBN 9780870230882 , p. 8. Limited preview in Google Book Search

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 2

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 6

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 9

- ↑ In the original: "Wendell said from then on, that he was determined to work for a better balance with a social conscience. If he ever got into a position of influence, he wanted to make the difference"; quoted from: Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 12

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 13

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 14

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 15-17

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 40 ff.

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 25-26

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 16-17

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 21

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 27

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 26-27

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 30

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 36

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 52-56

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 91f.

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 109 ff.

- ^ Charles Peters: Five Days in Philadelphia: The Amazing "We Want Wilkie!" Convention of 1940 and How It Freed FDR to Save the Western World . Public Affairs, New York 2006 p. 110f.

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 129-130

- ^ A b Franklin D. Roosevelt: Campaigns and elections. ( October 10, 2014 memento on the Internet Archive ) Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia.

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 191

- ↑ The choice of a candidate: Wendell Willkie 1940 , The New York Times, September 19, 1940 (English), online as PDF

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 181

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 192f.

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 195

- ↑ Susan Dunn: 1940: FDR, Willkie, Lindbergh, Hitler — the Election Amid the Storm. Yale University Press, New Haven 2013. p. 289

- ↑ Susan Dunn: 1940: FDR, Willkie, Lindbergh, Hitler — the Election Amid the Storm. Yale University Press, New Haven 2013. pp. 210f.

- ↑ Susan Dunn: 1940: FDR, Willkie, Lindbergh, Hitler — the Election Amid the Storm. Yale University Press, New Haven 2013. pp. 297f.

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 217ff.

- ↑ Susan Dunn: 1940: FDR, Willkie, Lindbergh, Hitler — the Election Amid the Storm. Yale University Press, New Haven 2013. p. 314

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 240

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 242ff.

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 262

- ↑ About us: Our history , Freedom House (English)

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 189

- ↑ Eleanor Roosevelt: My Day , The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Digital Edition (2017) , October 12, 1944 (English)

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 267

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 288

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 207 ff.

- ↑ David M. Jordan: FDR, Dewey, and the Election of 1944. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2011; P. 90 f.

- ↑ David M. Jordan: FDR, Dewey, and the Election of 1944. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2011; P. 91

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 309

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 317

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 321

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. pp. 318 ff.

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 323

- ^ Charles Peters: Five Days in Philadelphia: The Amazing "We Want Wilkie!" Convention of 1940 and How It Freed FDR to Save the Western World . Public Affairs, New York 2006 p. 171

- ^ Charles Peters: Five Days in Philadelphia: The Amazing "We Want Wilkie!" Convention of 1940 and How It Freed FDR to Save the Western World . Public Affairs, New York 2006 p. 194.

- ↑ In the original: "It is arguable that Willkie's impact on the United States and the world was greater than that of most men who actually held the office [of president]. At a crucial moment in history, he stood for the right things at the right time ". Quoted from: Charles Peters: Five Days in Philadelphia: The Amazing "We Want Wilkie!" Convention of 1940 and How It Freed FDR to Save the Western World . Public Affairs, New York 2006 p. 191

- ↑ Sheryl Stolberg: Disaffected Democrat Who Is Now a GOP Dream , The New York Times, September 2, 2004 (English)

- ^ Samuel Zipp: When Wendell Willkie Went Visiting: Between Interdependency and Exceptionalism in the Public Feeling for One World American Literary History, Volume 26, pp. 484f.

- ↑ In the original: "He launched the most successful and unprecedented challenge to conventional nationalism in modern American history ... He urged [Americans] to imagine and feel a new form of reciprocity with the world, one that millions of Americans responded to with unprecedented urgency" . Quoted from: Samuel Zipp: When Wendell Willkie Went Visiting: Between Interdependency and Exceptionalism in the Public Feeling for One World American Literary History, Volume 26, p. 505

- ↑ Steve Neal: Dark Horse: A Biography of Wendell Willkie . University Press of Kansas, 1989. p. 324

- ↑ David Stebene: Long before Trump, there was Wendell Willkie , Newsweek, March 19, 2016 (English)

- ↑ Bruce W. Dearstyne: Lessons Donald Trump Can Learn from Wendell Willkie , History News Network, June 26, 2016 (English)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Willkie, Wendell |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Willkie, Wendell Lewis (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American lawyer and businessman |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 18, 1892 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Elwood , Madison County , Indiana |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 8, 1944 |

| Place of death | New York City |