Attack on Pearl Harbor

| date | December 7, 1941 |

|---|---|

| place | Pearl Harbor , Oahu / Hawaii |

| output | Japanese victory |

| consequences | Entry of the United States into World War II |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Husband E. Kimmel |

Yamamoto Isoroku (Admiral), |

| Troop strength | |

| 8 battleships 8 cruisers 29 destroyers 9 submarines 391 warplanes |

6 aircraft carriers 2 battleships 3 cruisers 9 destroyers 6 submarines 441 combat aircraft |

| losses | |

|

5 sunken |

29 destroyed |

1941

Thailand - Malay Peninsula - Pearl Harbor - Hong Kong - Philippines - Guam - Wake - Force Z - Borneo

1942

Burma - Rabaul - Singapore - Sumatra - Timor - Australia - Java - Salamaua - Lae - Indian Ocean - Port Moresby - Coral Sea - Midway - North America - Buna-Gona - Kokoda-Track

The attack on Pearl Harbor , also known as the attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise attack by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Force in peacetime to in Pearl Harbor in Hawaii Territory at anchor Pacific Fleet of the United States on December 7 1941st

With the attack, the Japanese Empire expanded the Pacific War that had been waged since 1937 . With the attack, Japan wanted to shut down the US Pacific fleet for half a year in order to secure raw materials in Southeast Asia. On December 8, 1941, the United States declared war on Japan. On December 11, the Nazi German Reich, allied with Japan, and Italy declared war on the USA ( Germany and Italy declared war on the United States ). The attack on Pearl Harbor and its aftermath thus became a decisive turning point in World War II , because the United States' declaration of war on Japan and the Axis' declaration of war on the United States led to the United States' entry into World War II . Even before December 11th, the US had provided considerable material support ( lend lease ) to Great Britain and the Soviet Union , but they had remained formally neutral.

Much of the American Pacific Fleet was eliminated by the attack. This was particularly due to the fact that the commanders in Pearl Harbor had insufficiently prevented surprise attacks.

At the time of the attack, the aircraft carriers of the Pacific Fleet were not in Pearl Harbor and therefore were not hit. The Japanese had not attacked the fuel depots, shipyards and docks, which was useful to the Americans. A few hours before the attack, the Japanese offensive against the British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia ( Japanese invasion of the Malay Peninsula ) had begun . The attack on Pearl Harbor is seen as the battle, as a result of which the battleship was replaced as the dominant element of naval warfare by aircraft carriers, and especially aircraft.

Although the attack severely weakened the US militarily, the long-term consequences for Japan were fatal. Through the attack, which was perceived as " insidious " in the USA , the American government succeeded in mobilizing the US population , which had hitherto been largely pacifist or isolationist , to join the war, which, due to the enormous American industrial potential, led to the decision in favor of the Allies . The name Pearl Harbor is still considered a synonym in the USA for a devastating attack that took place without warning.

US-Japanese relations before the attack on Pearl Harbor

Since 1937, Japan waged the Second Sino-Japanese War in China . The United States was initially neutral, but its stance changed in favor of China in the following years because of the Panay incident and increased reports of Japanese atrocities such as the Nanking massacre . The USA increasingly sided with China. The US was concerned with protecting its own influence and economic interests in Asia. They delivered large quantities of war material to China. In addition, in early 1940 the US warned Japan not to invade French Indochina and demonstratively moved its Pacific fleet from its home base in San Diego on the west coast to Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands. When Japan stationed troops in Indochina in July 1940 despite an American warning , the American government under President Franklin D. Roosevelt restricted American exports of oil and steel to Japan in September 1940 (at that time Japan obtained 80% of its oil from the USA). When this did not have the desired effect and on July 24, 1941, after some pressure on the Vichy regime, Japan occupied French Indochina with 40,000 soldiers, the situation had worsened. Now Japan could cut off supplies for China and the way to the oil wells in the Dutch East Indies was free. As a result, on July 25, 1941, the USA imposed a complete oil embargo on Japan and froze all Japanese assets. As the United Kingdom and the Dutch East Indies followed suit, Japan lost 75% of its foreign trade and 90% of its oil imports.

Without the oil imports, Japan's reserves for industry and the military only lasted for a few months, so the Japanese leadership under Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō had to restore the oil supply within this time if they wanted to prevent the collapse of the empire. She saw only two options for this:

- either Japan had the embargo lifted through negotiations with Washington in return for Japanese concessions,

- or Japan forcibly secured its supplies of oil and other scarce resources by taking possession of the resource-rich Southeast Asian colonies of Great Britain and the Netherlands.

The majority of the Japanese leadership believed that an agreement with the US on terms acceptable to Japan was unlikely. Furthermore, even if an agreement was reached, Japan would continue to be dependent on foreign raw materials. The consequences of this addiction were acute. Japan nevertheless started negotiations with the American government, which finally led to the Hull Note on November 26, 1941 . This was taken as an ultimatum by Prime Minister Tōjō and the Japanese cabinet .

Meanwhile the military was preparing to attack the British and Dutch colonies in the south. From Japan's point of view, the opportunity was favorable, as the Netherlands had no armed forces worth mentioning and Great Britain's forces were tied up because of the war in Europe. In addition, the Automedon incident brought Japan into possession of the top secret strategic directives of the British General Staff for the Far East. These contained not only a detailed analysis of the existing British armed forces in Asia and the planned strategies in the event of war, but also the particularly valuable information on the extent to which Great Britain was willing to move forces from other fronts to Asia. As a result, the Japanese high command was better informed of the British vulnerability than most British commanders.

However, between Japan and the raw materials to be conquered still lay the Philippines , which at that time was a semi-autonomous colony of the USA. From there, the USA would have been able to interrupt the transport routes between raw materials in Southeast Asia and Japanese industry in the event of a war with Japan. The USA's entry into the war as a result of the Japanese attack in Southeast Asia was extremely unlikely due to the isolationism and pacifism that prevailed among the American population, but due to American policy in previous years, many Japanese military ultimately considered a conflict to be inevitable and therefore called for the occupation of the Philippines as part of the offensive. They pointed out that both the Philippines and other American possessions in the western Pacific, such as Guam and Wake, were poorly defended ( the US Navy’s Asian fleet only had three cruisers and 13 obsolete destroyers), but this could change quickly. In addition, after the outbreak of war in Europe, the United States began a massive expansion of its fleet, which included ten South Dakota and Iowa -class battleships and nine large Essex-class aircraft carriers . These units under construction alone formed a fleet that was stronger than the entire Japanese fleet built in 30 years. Furthermore, in 1941 Japan could hope that the war in Europe would tie up some of American resources. At a later date, it would have to fight alone.

In contrast, there was a smaller group of officers and politicians who warned of war with the United States. They referred to the enormous industrial capabilities of the USA, which not only built this huge fleet, but at the same time produced huge amounts of armaments for Great Britain and the Soviet Union (see Lending and Lease Act ), without this restricting the production of civilian consumer goods led. In 1940, around 4.5 million trucks were built in the United States and only 48,000 in Japan. One of the most prominent opponents of a war with the USA was originally Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku , Commander in Chief of the Combined Fleet and former Japanese naval attaché in Washington. Regarding the prospect of winning such a war, he said: “If I receive an order to wage war regardless of the consequences, I will fight wildly for 6 months or 1 year. But if the war lasts a second or third year, I see it extremely black! ”. Nobody believed that the war could be won within a year. Nevertheless, in late November 1941, the Japanese leadership finally decided to go to war against the United States. Yamamoto was nevertheless the one who succeeded against resistance to waging an annihilation blow against the Pacific Fleet in order to gain time for the conquest of territories in Southeast Asia.

In Washington, diplomatic negotiations appeared to continue until the morning of December 7th. On December 6, Tokyo began delivering a 14-piece note to the Japanese embassy in Washington to be delivered to the US Secretary of State at 1:00 p.m. Washington time (30 minutes before the attack was scheduled to begin). With this note, Japan officially informed the USA that the US government did not see any point in further negotiations and would therefore break them off. Contrary to popular opinion today, the note did not contain a declaration of war by Japan. The decisive 14th part, which contained the termination of the negotiations, was not sent until the night of December 7th. Although the note had already been translated into English by Tokyo and only had to be deciphered, the preparation of the note took too long. This was due in large part to the fact that the sleepy embassy employee, who had to type the text again with the typewriter after it was decrypted, made so many typing errors at the beginning that he finally decided to throw away the first few pages and retype them again write. But the decryption also took longer than Tokyo expected. As a result, the note was only given several hours after the attack.

The US Pacific Fleet

In the pre-war period, the Pacific Fleet had always been considerably stronger than the Atlantic Fleet . According to the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, the USA was allowed to own 15 battleships and six aircraft carriers, of which twelve battleships and four carriers were assigned to the Pacific Fleet. These were also the most powerful ships, the three battleships of the Atlantic fleet ( Arkansas , New York , Texas ) were the oldest of the fleet. The reason for this unilateral distribution was that in the Pacific, Japan, a potential enemy, had the third largest fleet in the world, while the largest fleets in the Atlantic belonged to Great Britain and France, with which no conflict was expected.

This changed when, with the defeat of France in 1940, the French fleet was neutralized and the Royal Navy had to fight the German and Italian fleets alone in the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

In order to relieve Great Britain as much as possible, the USA extended its neutrality patrol further and further into the Atlantic. For example, American cruisers monitored the Denmark Strait and American destroyers escorted convoys in the western Atlantic until they were taken over by British destroyers for the most dangerous part of the way. To this end, a quarter of the Pacific fleet was moved to the Atlantic, including the battleships New Mexico , Mississippi , Idaho and the aircraft carrier Yorktown . In addition, almost all newly built aircraft were either used in the Atlantic or delivered directly to Great Britain under loan and lease law ; American forces in the Pacific had to make do with what they had.

Nevertheless, the Pacific Fleet was quite strong by the standards that had been valid until then, which were based on a battle decision by battleships. It had nine battleships with a total of 24 guns of 406 mm (16 inch) and 68 guns of 356 mm (14 inch) against ten Japanese battleships with a total of 16 guns of 406 mm (16 inch) and 80 guns of 356 mm (14 inches).

The core of the battle fleet was formed by the big five , the five battleships of the Tennessee and Colorado classes. These battleships, built after the First World War, were the most powerful in the fleet between the two world wars. In terms of their artillery and armor, they were still on a par with the most modern battleships in the world at that time, such as the British King George V class or the German Tirpitz . Only in terms of speed they were meanwhile inferior to modern battleships with their relatively slow 22 knots. However, since the Japanese fleet itself also consisted of battleships that had been built during or immediately after the First World War, this disadvantage did not come into play in the Pacific.

The aircraft carriers had a ratio of three American to ten Japanese (including four smaller carriers), but the role of the carriers was seen more in supporting the battleships through aerial reconnaissance.

Preparations

For a long time, US plans for a war against Japan were based on the War Plan Orange , according to which the US Pacific Fleet would run from its home base in San Diego to the Philippines in the event of war to defend it against a Japanese attack and then as a base to use for an advance against Japan itself. In the course of these operations there would then be a major decisive battle between the battleships. The possibility of opening the war by a Japanese surprise attack similar to the attack on Port Arthur at the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 was considered quite possible. One thought, however, of an attack on Manila , the base of the weak American Asian fleet, or the island of Wake . However, the US Pacific Fleet at its home base in San Diego was well beyond the operational range of the Japanese fleet.

With the relocation of the Pacific fleet to Pearl Harbor in 1940, this changed - Pearl Harbor was just within the range in which Japanese naval units could operate with reasonable effort. The way there and back could be accomplished with a single refueling at sea. However, when Japan began planning an attack, difficulties were quickly encountered. The topographical shape of the port, practically an inland body of water only connected to the sea by a natural channel, made a torpedo attack with destroyers like the one carried out in Port Arthur in 1904 impossible. The destroyers would have had to run through the canal into the port to get a clear field of fire for their torpedoes. They inevitably had to be discovered and shot down.

An air strike was investigated as an alternative. This, too, was not a completely new idea: during a joint exercise by the American Army and Navy in defense of Hawaii in 1932, Admiral Harry E. Yarnell , commander of the attacking forces, had the squadrons of the Saratoga and Lexington aircraft carriers fly an attack on Hawaii. By this attack carried out on February 7, 1932 (like December 7, 1941 a Sunday) from the northwest, the surprised defenders were, in the opinion of the referees, caused considerable damage. It is quite possible that this maneuver also influenced the Japanese planning, although the American Navy rejected the results as unrealistic at the time.

However, the template for the attack was provided by the British in the Mediterranean when they attacked the Italian naval port of Taranto with torpedo bombers from the aircraft carrier Illustrious on the night of November 11th to 12th, 1940 , and sank three Italian battleships. This attack was intensively investigated by both the Japanese and the American admiralty staff, as the conditions in Taranto were very similar to those in Pearl Harbor, especially with regard to the use of torpedoes . The use of torpedoes was imperative, according to the planners, as it was the only weapon with which aircraft could attack battleships with any prospect of success.

The available bombs, however, were generally not able to penetrate the massive armor of the battleships and cause major damage. Since torpedoes dropped by aircraft first sank to a greater depth due to their weight before the built-in depth control steered them back up, shallow harbors such as Taranto and Pearl Harbor were considered safe. In order to prevent the torpedoes from hitting the bottom in the harbor and getting stuck there, the torpedoes with small wings had been modified so that they remained in a horizontal position for longer after being released and not, as usual, dipping into the water at an angle increasing with the height of the discharge. In addition, the British pilots had flown extremely slowly and low. The Americans got this information from the British. Japanese officers were able to see a recovered British torpedo in Taranto.

The US Navy revised its guidelines regarding the torpedo protection of ships in port due to the attack. Until then, a water depth of 76 feet (23 meters) was considered the minimum for a successful torpedo attack from the air. In June 1941, this was corrected with reference to the attack on Taranto, so that torpedo attacks were also possible at shallower water depths. Attacks at a water depth of less than 20 meters were classified as unlikely, so Pearl Harbor was still considered safe at an average water depth of 15 meters. The Americans also believed that a comparable attack on Pearl Harbor was unlikely, as the distance between Taranto and the British base in Alexandria was much less than that between Pearl Harbor and the nearest Japanese bases. The unnoticed approach of an enemy was therefore considerably more difficult. In addition, the Japanese Nakajima B5N Kate torpedo bombers could not fly as slowly as the old Fairey Swordfish biplanes of the British, which in their opinion precluded the use of the British method.

The Japanese, however, came to the conclusion that a torpedo attack would be feasible if the torpedoes were modified accordingly. This led to the development of the Type 95 torpedo , which was smaller and lighter than the usual Japanese torpedoes. In addition, armor-piercing shells of caliber 356 mm and 406 mm were modified so that they could be dropped as bombs. Thrown from a height of at least 3,000 meters, they should have sufficient penetration to penetrate the armor of the battleships. It was one of those tank explosive bombs that hit the Arizona ammunition chamber.

The plan

The plan as quoted by Admiral Yamamoto :

“At the beginning of the war, the task force, consisting of six aircraft carriers as a core and commanded by the Commander in Chief of the 1st Air Fleet, is to continue its way to the Hawaiian Islands and attack the main forces of the US fleet anchored in the port from the air. The task force will therefore leave the homeland about two weeks before the outbreak of hostilities, approach the Hawaiian Islands from the north and take off all aircraft on board the carriers, about 400, an hour or two before daybreak. The surprise attack on the anchored enemy aircraft carriers and ships as well as aircraft on the ground will be launched from a point about 200 nm north of the island of Oahu.

The submarine formation, consisting of 27 submarines and commanded by the Commander in Chief of the 6th Fleet, will continue to explore the movement of the enemy fleet anchored in Hawaii and begin operations a few days before hostilities begin. If the enemy fleet leaves port, the submarine formation will launch a surprise attack or try to keep in touch with them. On the other hand, the submarine unit will be subordinated to the special attack unit, which will advance undetected into the Pearl Harbor and at the same time launch a surprise attack on the enemy fleet with the air strikes of the task force. "

According to the Japanese plan of attack, the aircraft carrier formation was supposed to approach Pearl Harbor unnoticed in a journey of eleven days on a route about 6,000 kilometers north of the usual shipping lanes and to attack surprisingly from a distance of 350 kilometers north of the base. Since most of the US armed forces only worked with reduced staff on Sundays, the first Sunday in December, December 7th, was chosen as the date of the attack. The attack was to be carried out by the Kidō Butai , consisting of the six aircraft carriers Akagi , Kaga , Hiryū , Sōryū , Zuikaku and Shōkaku . The escort of the porters consisted of the fast battleships Hiei and Kirishima , the heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma, and 9 destroyers led by the light cruiser Nagara .

The main strategic objectives of the attack were:

- Neutralization of the Pacific Fleet : By eliminating the battleships and aircraft carriers, the American fleet should not be able to obstruct the Japanese offensive in Southeast Asia. The attacking pilots were given specific instructions to only attack battleships and carriers and not to “waste” their torpedoes and bombs on other ships (not all of them obeyed orders during the attack).

- Elimination of the Pearl Harbor base : Destroying the docking facilities and fuel tanks should make it impossible for the USA to operate from Pearl Harbor for the foreseeable future. The Pearl Harbor docks were the only facilities west of California where repairs and major maintenance could be done. If they were destroyed, American ships had to travel halfway across the Pacific to the west coast even for minor repairs. Ideally, the sinking of a large ship in the Pearl Harbor access channel would even fail as an anchorage, so that the entire fleet would first have to come from the west coast for each operation.

Another goal was added for tactical reasons:

- Destruction of the air force : The American airfields had to be attacked so that the fighters stationed there did not hinder the attacks on the port and the bombers did not counter-attack the attack force (if it could be located).

Since not enough aircraft were available to perform all three tasks at the same time, it was decided to attack only the ships and the airfields first. As soon as the machines returned, they should be refueled and ammunitioned to attack the docks and fuel tanks.

The first attack should be made as early as dawn. Since the porters at that time did not use catapults, half the deck was always required as a runway. This meant that only half of the aircraft could be brought on deck to take off at the same time. The second half could only be made ready after the first half had started. Since the preparations for take-off took at least 30 minutes, it was decided to fly the first attack in two waves: the first half flew ahead, the second followed as quickly as you could get it ready.

The first wave was to consist of 45 A6M Zero fighters , 54 D3A Val dive bombers and 90 B5N Kate torpedo bombers . Forty of the cottages were to carry torpedoes, the rest of them bombs. The second wave should consist of 36 Zero , 81 Val and 54 Kate (all with bombs).

Since the surprise of this attack was elementary, the commander of the attack group, Vice Admiral Nagumo Chuichi , had orders to turn back immediately if he was discovered on the march. If it wasn't discovered until the morning of the attack day, it was up to him whether he wanted to risk the attack. In no case should he expose his ships to unnecessary risks, as they were irreplaceable for Japan.

The assault unit left Japan on November 26, 1941 from the waters in the Kuril Islands . During the journey, Admiral Yamamoto sent a coded message to Nagumo on December 2nd: Niitaka yama Nobore (Climb Mount Niitaka) , giving the final order to carry out the attack.

Japanese espionage

The Japanese spy Takeo Yoshikawa came to Honolulu in March 1941. Disguised as an employee of the Consulate General, he had officially entered the country. With more than a third of the population in Hawaii of Japanese descent, Yoshikawa had no problem posing as a local. Yoshikawa knew exactly when which capital ships were in port and at what rhythm they left. He knew details of the military establishment rosters and knew that the main airport, Hickham Air Field, had no air defenses to speak of . During the first few months of his deployment, Yoshikawa sent a monthly report on the status of the US fleet in Hawaii, twice a week from mid-November and daily from December 2, 1941. Yoshikawa received help from the Japanese consul in Honolulu , Nagao Kita .

His reports were encrypted using the Japanese diplomatic service's encryption system. Although this could in principle be cracked by the cryptanalysts of the US War Department, a suitable decryption should have been found for each day and for each place of origin of a message. Most of the telegrams sent by the Kita were not decrypted until much too late by the other side.

The German couple Bernard and Friedel Kühn, together with their daughter Ruth, collected information on the island and sent it to Tokyo via the consulate. They became Japanese agents in 1936 at the suggestion of the Nazi state . With forged papers they came to Hawaii disguised as a family of professors. Ruth used to deal with American officers there and obtained secret information. The Kühns built a house in Pearl Harbor with a view of the US naval base on behalf of the Japanese.

The American radio reconnaissance

American telecommunications intelligence was divided into three areas:

- The radio direction finding department was responsible for locating the senders of intercepted radio messages. To this end, the USA had set up a network of listening stations, the Mid-Pacific Strategic Direction-Finder Net . It stretched in a huge semicircle from the Philippines to Guam , Samoa , Midway and Hawaii up to Alaska .

- In the area of radio traffic analysis, the patterns of the intercepted radio messages were analyzed. The call signs were used to determine who was speaking to whom. From the frequency of communication one tried to find out the relationship between the stations. For example, if the NOTA 1 and OYO 5 stations spoke frequently to KUNA 2, but rarely to each other and not at all to others, it could be assumed that KUNA 2 was the commander of NOTA 1 and OYO 5, for example the flagship of a squadron that owns the ships NOTA 1 and OYO 5 were assigned. With the help of the radio direction finding, the assignment of the call signs was possible if one knew which units / ships were at the transmission position at the time of transmission.

- The cryptanalysis department was responsible for deciphering the captured messages. This was the most difficult and secret part of the radio reconnaissance. Since it was extremely important to keep secret the fact that the Japanese code had been cracked, the information obtained was only made available to a small group of high-ranking officers and politicians, while the results of the direction finding and radio traffic analysis were made available to a much larger group were accessible. For example, the commanders in Hawaii, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel and General Walter C. Short , were given access to the results from radio direction finding and radio traffic analysis, but not from the cryptanalysis, while the commanders in the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur , had access to all information would have.

In the course of November 1941, the radio reconnaissance based on the Japanese radio pattern determined the preparation of a major operation. These patterns corresponded to the three phases that had already been observed in the preparations for the two operations to occupy Indochina.

- First phase: there was a sharp increase in radio traffic. The high command issued orders and instructions for the operation to the army and naval commanders. These instructions were passed through the entire hierarchy to the units that had to prepare for the operation. In this way one could often identify the units involved by checking which callsigns were involved in the increased radio traffic. However, since the Japanese fleet carried out its semi-annual call sign change for its 20,000 call signs on November 1st, many call signs had not yet been identified. However, it was found that the Japanese high command mainly communicated with the southern commanders, but not with the commanders in China.

- Second phase: the radio traffic dropped back to the normal amount of messages. The units involved had prepared according to the instructions and were waiting for orders to begin operations. Changes in the radio patterns that had arisen through regrouping could be determined. Stations suddenly communicated with new stations, but no longer with their previous communication partners.

- Third phase: the number of radio messages decreased rapidly and became one-sided. The operation had begun, the naval formations had left and had radio silence to prevent a targeting of their position. However, they continued to receive radio messages addressed to them from other units (the radio silence therefore only affected the transmission, not the reception of the operational units).

On December 1st, the Japanese fleet changed their callsigns again. This unscheduled change also alerted the intelligence services.

In this way it was known from radio direction finding and radio traffic analysis alone that Japan wanted to carry out a large operation southwards. The target was not clear, however, it could be an attack on the British and Dutch colonies (which was suspected), an attack on the Philippines or further troop transfers to Indochina (which were considered unlikely). On November 24 and 27, the Chief of Naval Operations , Admiral Harold R. Stark , sent war warnings to all commanders in the Pacific, informing them that aggressive action by Japan could be expected in the next few days. Malaysia , Thailand , the Philippines, Borneo and Guam were named as possible targets for a Japanese attack . All commanders in the Pacific were instructed to take appropriate measures to prepare their troops for war, but not to carry out any offensive action themselves as long as Japan did not undertake an open act of war against the United States.

The British and Dutch intelligence agencies, who worked with the Americans to intercept and analyze the news, had the same picture. Great Britain then began to increase its troops as far as possible: It moved the modern battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse to Singapore .

The Japanese sponsoring associations were a special case. Nobody knew anything about them, as there was total radio silence. That the carrier associations not just any messages sent, but also no news to sent them led to believe that the carriers still stayed in the Japanese home waters. There they were able to communicate via weaker short-range transmitters whose transmission power was too weak to be received by the distant listening stations. This blackout had already been observed during the previous operations. At that time, too, the porters were suspected to be in Japan and later found in various ways that they had actually been there. The suspected remaining of the porters in Japan aroused no suspicion, because it fit in perfectly with the overall picture. According to the analysts, the carriers were not needed for an offensive against the British and Dutch colonies alone; instead, together with several battleships, they formed a strategic reserve in case the US would come to Britain's aid. In fact, however, the association was under radio silence on the way to Pearl Harbor. Messages to him were hidden in general radio messages addressed to large areas of the fleet.

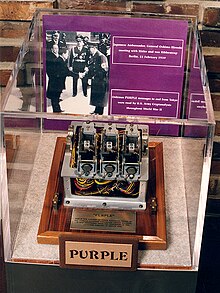

The department responsible for cryptanalysis has now had major problems with the amount of intercepted material. In addition to deciphering the messages, it had to be translated from Japanese into English. The small number of translators , who were responsible not only for military but also for diplomatic communications, could no longer keep pace with the considerably increased volume. Attempts were made to increase the number, but this was difficult. The translators not only had to be able to speak excellent Japanese, they also had to be absolutely trustworthy. Such people were few and far between, and mostly Japanese Americans, who were generally distrusted. In 1941, the naval department for cryptanalysis managed to double the number of translators from three to six people, despite the greatest efforts. As a result, translations were ranked according to the type of encryption. First came diplomatic communications encrypted with the “Purple” key machine, then communications encrypted with high-security military codes, and then texts encrypted with simpler Japanese codes. In this way, instructions encrypted with Purple were sent to the Japanese embassies in Great Britain and the Dutch East Indies to send their "Purple" machines back to Japan and prepare for the destruction of their remaining codes. This confirmed the suspicion of an imminent war with these countries. Corresponding instructions to the consulates in the USA, which did not have "Purple" machines, were not translated, however. The only "Purple" machines in the US were in the Japanese embassy in Washington, where they were still needed. The fact that there were initially no instructions to send these machines back to Japan was interpreted to mean that no attack on the USA was planned. It wasn't until December 3 that the Washington embassy received an order to destroy one of its two key machines and much of its codes, making the possibility of war between the US and Japan much more likely to analysts.

The decrypted military messages contained nothing useful to further identify the targets. Nor was this to be expected. On December 6th, the first 13 parts of the 14-part Japanese note to be delivered on December 7th were received and decrypted. Although the 14th part with the most important information was still missing (the first 13 parts mostly contained a historical outline of the relations between the USA and Japan, in which the USA was accused of hostility towards Japan, but nothing about the intended Japanese policy), the 13 parts that had already been received were brought to all persons that evening who were authorized to see this secret information. After reviewing the contents, President Roosevelt said to his adviser Harry Hopkins , "This means war." After briefly discussing the well-known Japanese naval and troop movements in Southeast Asia, Hopkins said he would prefer the United States to strike first and thus avoid any surprises. Roosevelt replied that such a thing cannot be done as a peace-loving democracy. Roosevelt wanted to talk to Admiral Stark on the phone, but he was in the theater. Calling him out was possible, but would have caused a stir, which the President wanted to avoid.

All other people who received the first 13 parts in the evening wanted to wait for the 14th part before taking action. To this end, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox arranged a conference with Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and Secretary of State Cordell Hull the following morning. Even Admiral Stark, who only learned of the existence of the Japanese note from the chief of the naval intelligence service late in the evening , merely ordered that the full note be brought to his office the next morning. The Army Chief of Staff , General George C. Marshall , did not see the note because he was already asleep and no one wanted to wake him. The next morning he went for a ride after breakfast and was therefore not to be found for a long time when they wanted to bring him part 14.

The instruction to the Japanese embassy in Washington to destroy its remaining codes and the second key machine came with the text accompanying the 14th part of the Japanese note of December 7th, which also contained the instruction to write the note at 1:00 p.m. Washingtoners Local time (7:30 a.m. in Pearl Harbor). The translation of the accompanying text reached the intelligence officer in charge, Lieutenant Commander Alwin D. Kramer, at 10:20 a.m. Washington time, just under three hours before the start of the attack on Pearl Harbor. He immediately relayed the message, and at about 11:30 am, General Marshall ordered all overseas commanders to be warned of possible Japanese action, with the Philippines as a top priority. However, this news did not reach Pearl Harbor in time. It also had little effect in the Philippines and other bases in the Pacific such as Wake and Guam, as the time remaining before the Japanese attack began was too short.

Pearl Harbor on December 7th

Since a Japanese attack was not seriously expected in Hawaii, the berths of the battleships around Ford Island were not secured. Most of the crews went ashore. The fires under the ships' boilers were either fully or half extinguished. Without a fire under the boilers, the ships could not generate steam for their engines and lighting a boiler took several hours until sufficient steam pressure was built up.

The US Army was responsible for defending the island itself . Here, too, the troops were in no way prepared for an attack. The anti-aircraft guns were not distributed around the military installations, but were in depots, as the surrounding properties were private property, the owners of which one did not want to annoy unnecessarily. For example, the army flak at the newly built Kāneʻohe Naval Air Station had been moved back to the barracks a few days earlier. The anti-aircraft ammunition was stored in separate ammunition depots, these were locked like all other ammunition depots. In some cases, the key holders are said to have refused to open the ammunition chambers without a written order during the attack. On the instructions of General Short, all aircraft at the airfields had been moved from their usual positions on the edge of the field and the shelters in the middle of the field, as this would provide better protection against sabotage . The six new mobile radar stations, which had only arrived in the Hawaii Territory in October 1941, only worked between 4:00 a.m. and 7:00 a.m. The decision not to use the radar around the clock, but only at the most likely time of attack, was due, among other things, to the skepticism that this new technology was still met with despite its successful use in the Battle of Britain . The fact that the period between 4:00 a.m. and 7:00 a.m. was considered the most likely point in time for an attack also showed that the possibility of an attack was well known and (quite correctly) assumed that such an attack would occur at the earliest possible point in time Sunrise would take place. A Japanese attack was therefore not considered impossible, but based on the current assessment of the situation, it was extremely unlikely.

Water depths:

Targets attacked:

1: USS California

2: USS Maryland

3: USS Oklahoma

4: USS Tennessee

5: USS West Virginia

6: USS Arizona

7: USS Nevada

8: USS Pennsylvania

9: Ford Island NAS

10: Hickam Field

spared targets:

A: Oil tanks

B: CINCPAC headquarters

C: Submarine base

D: Naval shipyard

Naval units in Pearl Harbor:

- Nevada , Oklahoma , Pennsylvania , Arizona , Tennessee , California , Maryland , West Virginia

- Except for the Pennsylvania , which was in dry dock, the battleships were anchored in a row off Ford Island in the middle of the port (Battleship Row) . The Pacific Fleet's ninth battleship, the Colorado , was in Bremerton , where it was upgraded at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard .

- No.

- The aircraft carrier Enterprise was scheduled to arrive on December 6th, having transported a squadron of fighters to Wake Island with three cruisers and nine destroyers (a task that was not unusual at the time for an aircraft carrier). However, the association had to walk through a storm en route, resulting in a 24 hour delay and not arriving until the afternoon of the 7th. The Lexington transported another fighter squadron to Midway with three cruisers and five destroyers. Since the relocation of the two squadrons should be kept secret if possible, the porters were officially on training missions. Partly this camouflage story has held up to this day; Quite a few articles and books still state that the porters left port to practice shortly before the attack (the Lexington left on December 5th). However, at least for the Enterprise, participation in an exercise with the first battleship division ( Arizona , Nevada and Oklahoma ) had been planned in this period. The exercise then took place without them, and the battleships returned to Pearl Harbor on December 5th.

- The last of the three carriers of the Pacific Fleet, the Saratoga , was en route to San Diego after a shipyard in Bremerton.

- Raleigh , Detroit , Phoenix , Honolulu , St. Louis , Helena , New Orleans , San Francisco

- Ward (out of port), Helm , Phelps , MacDonough , Worden , Dewey , Hull , Monaghan , Farragut , Dale , Aylwin , Henley , Patterson , Ralph Talbot , Selfridge , Case , Tucker , Reid , Conyngham , Blue , Allen , Chew , Shaw , Downes , Cassin , Mugford , Jarvis , Schley , Cummings , Bagley

- Zane , Wasmuth , Trever , Perry , Turkey , Bobolink , Rail , Tern , Grebe , Vireo , Cockatoo , Crossbill , Condor , Reedbird

- PT-20 , PT-21 , PT-22 , PT-23 , PT-24 , PT-25 ; PT-26 and PT-28 were on the quay ; on deck of the tanker Ramapo PT-27 , PT-29 , PT-30 and PT-42

- Submarine rescue ship

The Japanese high command was informed about the ships in the port, since the Japanese consulate in Hawaii continuously reported its observations of the port to Tokyo (such observations belonged to the standard tasks of the consulates of all countries). From Tokyo, the reports were forwarded to the fleet (and thus Nagumo). This ensured (as far as possible) that the Pacific fleet was in Pearl Harbor and Nagumo was not attacking an empty port. However, both Nagumo and the Japanese High Command knew 24 hours before the attack that there were no aircraft carriers.

The attack

Preparations

On the evening of December 6th, the incoming Kidō Butai reduced her speed to about 25 knots. Vice Admiral Nagumo made one final broadcast from the Akagi to all of his units. With the words: “The fate of the empire depends on this operation. Every man has to give himself totally to his special task. “He swore the ship's crews and especially the crews of the aircraft squadrons that were supposed to fly the attack.

By 9:00 p.m. the fleet had reached the 158th meridian and was about 910 kilometers north of Hawaii. Violent winds had torn the hoisted flags during the twelve-day voyage and more than ten sailors had been washed overboard. But everything went according to plan, as the fleet had not yet been sighted by other ships or reconnaissance aircraft.

approach

The first wave of Japanese attacks with 183 machines started at 6:10 a.m. local time on the morning of December 7, 1941, about 230 nautical miles (400 kilometers) north of Oahu. However, it took 20 minutes longer than planned to form over the girders. Six machines that did not start in time remained behind and started the second wave an hour later. The crews of the porters said goodbye to the machines taking off with banzai shouts. At the same time , 18 SBD Dauntless took off from the American aircraft carrier Enterprise , which was about 370 miles west of Pearl Harbor, and were supposed to fly ahead to Ford Island.

The first clash between the armed forces of Japan and the United States occurred at 6:37 a.m. local time in front of the port entrance. During the night a periscope was believed to have been seen on board the Condor mine sweeper near the port entrance and the destroyer Ward patrolling the port entrance had been alerted. However, this could not find a submarine. At around 06:30, the supply ship Antares reported the sighting of a submarine, whereupon the Navy launched a PBY Catalina flying boat to assist the Ward . At around 6:45 am, the Ward found and sank the submarine with gunfire and depth charges. It was one of five small Japanese submarines belonging to the U-Boot-Spezialverband, which were supposed to try to penetrate the port. A few minutes later, the Catalina reported the sinking of another submarine in front of the port entrance. The Ward's commander , Lieutenant Outerbridge, who had taken over the Ward as his first command two days earlier , sent an encrypted message to the Commander of the 14th Marine District to inform him that he was fighting a submarine in the Port Defense Zone. Delayed by the routine decryption process (including text reformulation so that plain text that had got into the wrong hands could not be used to break into the code used), the message reached the officers on duty at around 07:15 a.m. and was forwarded from there to Admiral Kimmel. In view of numerous false submarine reports in the previous weeks, however, Kimmel wanted to wait for confirmation of the report before taking action.

At 7:02 a.m., the two radar monitors from the Opanah Radar station spotted a group of 50 or more aircraft 130 miles away approaching from the north. The Opanah radar station was one of six of the Army's new mobile radar systems that had been in use on Oahu for less than a month. They were devices of the type SCR-270, a variant with a greater range of the SCR-268 series. After a brief discussion, they called the information center at Fort Shafter and reported the location of approaching aircraft, but without mentioning the number of machines located. The report was received by a lieutenant who was only on duty at the information center for the second time and did not ask any further questions. He knew a group of B-17 Flying Fortress bombers was expected and believed that these machines had been located. Since he was not allowed to share this confidential information with the radar observers, he only told them to end their duty (the radar was only on between 4 and 7 a.m.) and not to worry about the aircraft (“Don 't worry about it. ").

First attack

The first wave of Japanese attacks reached Pearl Harbor without encountering any resistance. She had shot down several American planes on the way. At least one of these machines still managed to send a radio message, but the content was difficult to understand. At 0749, the attack wave commander, Sea Captain Fuchida Mitsuo , ordered the complete surprise attack to be carried out, with the torpedo bombers first. His radio operator then sent the corresponding signal three times, consisting of to for totsugeki (attack) and ra for raigeki (lightning) (lightning / surprise attack). The signal to ra, to ra, to ra was also received on the carrier association, who knew that the surprise had been successful. American radio operators heard it too, but understood tora , the Japanese word for tiger. This led to the radio message becoming known as Tora, tora, tora .

The attack on the port began at 07:55 with the bombing of Ford Island. Three minutes later the radio station there sent the warning “Air raid on Pearl Harbor. This is not an exercise ”. The news was also received in Washington and communicated to Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, just minutes after the attack began . Fixated on the Philippines like the rest of the management level, he didn't want to believe it at first: " That can't be true, the Philippines must mean " (My God! This can't be true, this must mean the Philippines.) .

The Japanese armed forces initially had difficulty in forming. A signal missile was supposed to signal the pilots that they were still undetected. However, many did not see them and in the chaos all bombers attacked at the same time. 24 of the 40 Japanese torpedo bombers attacked the American battleships lying on the east side of Ford Island. The Nevada managed to shoot down two attacking machines before being hit by a torpedo and two bombs. The California received two torpedo hits and two bomb hits, one of the bomb hits detonated a magazine with flak ammunition. Since not all watertight bulkheads were secured, severe water ingress occurred that could not be controlled, which is why the ship finally had to be abandoned. On the Oklahoma the first attacking machines scored three torpedo hits, after which the ship began to capsize. During the capsizing, at least two more torpedoes hit the sides and superstructure of the battleship. Over 400 sailors were trapped below deck, 32 of them were freed from the wreck in the following days. The West Virginia was hit by at least six torpedoes, but rapid counter-tide prevented the ship from capsizing and the West Virginia sank on a level keel. In addition, she was hit by two bombs that set off a fire on the quarterdeck. Fragments from a bomb hit on neighboring Tennessee fatally wounded the commander, Captain Mervyn Sharp Bennion . The Arizona was presumably hit by a torpedo that passed under the workshop ship Vestal lying next to her before an anti-tank bomb hit between the two front main towers at 8:10 a.m. The bomb set off a chain reaction that led to the explosion of the front main magazines containing over 450 tons of powder. The huge explosion raised the battleship five to six meters, breaking it in two. The front part of the ship was practically completely destroyed, and the explosion ignited spilled oil on the surface of the water. 1177 of the 1400-strong crew died, half of all American dead in the attack, including the commander Franklin Van Valkenburgh and Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd . The Arizona burned for two days after the attack. The battleships Maryland and Tennessee lying on the inside of Battleship Row were relatively easily damaged; they could not be hit by torpedoes, as Ford Island on one side and the outer battleships Oklahoma and West Virginia on the other side were in the way. Both ships were hit by two bombs each , causing two of the twelve 356 mm guns on the Tennessee to fail. The thick clouds of smoke that rose after the Arizona explosion made it difficult for the Japanese bombardiers to aim at the two ships. The stern of the Tennessee , which was trapped by the sunken ships , suffered severe damage from the effects of heat as it lay in the burning oil of Arizona for two days .

At the same time, the remaining 16 torpedo bombers attacked the northwest side of Ford Island, where the berths of the aircraft carriers were also. Only the cruisers Detroit and Raleigh , the seaplane tender Tangier (AV-8) and the old battleship USS Utah, which had been converted into a training ship for anti-aircraft gunners, were located there . Under orders to attack only battleships and carriers, most of the bombers turned away, but some carried out the attack anyway. They may have misidentified the ships, mistaking the Utah for one of the newer battleships to take out. The Utah was hit by two torpedoes and capsized after ten minutes. The Raleigh received a torpedo hit, but managed to keep afloat with some difficulty. The remaining torpedo bombers flew over Ford Island and then started an attack on the battleships, except for one machine that dropped its torpedo on the cruiser Helena . The torpedo ran under the Oglala mine- layer lying next to the Helena and hit the cruiser amidships, flooding an engine room. The detonation caused such severe damage to the Oglala that it capsized two hours later.

At the same time as the torpedo bombers attacked, dive bombers and fighters attacked Ewa, Hickam Field , Wheeler Field, Ford Island and Kāneʻohe airfields . The American planes lined up next to each other were easy targets, especially at the Hickam and Wheeler airfields, but the other airfields didn't fare much better either. Besides Bellows Field, which was only shot at by a single fighter, only the small Hale'iwa airfield was spared. Most of the aircraft were devastated or damaged. Only a handful of American P-36 Hawk and P-40 Warhawk fighters managed to launch. The most successful were the pilots Kenneth M. Taylor and George Welch , who landed twice during the attack to take new ammunition and shot down a total of six Japanese machines. During the attack, the expected B-17 bombers also arrived, but they had no on-board weapons and after the long flight no more fuel reserves. They had no choice but to try to land somewhere in the middle of the attack, which all eleven planes managed to do despite attacks by Japanese fighters (one of the bombers landed on a golf course). The arriving aircraft from the aircraft carrier Enterprise were less fortunate . They were fired at not only by Japanese fighters, but also by American flak and lost six of the 18 bombers.

After the last machines of the first wave had flown off, there was a short break. Several American ships sailed out of port for the relative protection of the open sea, most of them without full crew. For example, the destroyer Blue ran out under the command of four Ensigns , no regular officer was on board. On the way to the port exit, crew members of the cruiser St. Louis suddenly saw two torpedoes running towards the ship, but they exploded against an underwater obstacle. They were probably shot down by one of the Japanese micro-submarines. The destroyer Helm sighted another micro-submarine at the port exit, his attack on the boat was unsuccessful, but the submarine was stranded on a reef. One of the two crew members drowned, the other, Lieutenant Sakamaki Kazuo , became the Americans' first Japanese prisoner of war. The destroyer Monaghan (DD-354) also spotted a submarine in the port basin while sailing, which he sank with depth charges. Of the battleships, the USS Nevada was the only one that managed to cast off, as the Maryland and Tennessee were blocked by the sunken Oklahoma and West Virginia .

Second attack

The Nevada had not yet left the port basin when the second Japanese attack wave, consisting of dive and horizontal bombers, arrived at 8:50 a.m. 23 bombers attacked the Nevada in the hope of sinking the battleship in the narrow access channel and thereby blocking the port. They scored at least five direct hits, two of which punched holes in the torso. When it became clear that the Nevada would not get through the canal, the commanding officers decided to turn away and aground the battleship at Hospital Point .

The battleship Pennsylvania was in dry dock during the attack, along with the destroyers Cassin and Downes , who lay side by side in front of the battleship. The first wave of Japanese attacks completely overlooked the Pennsylvania , only the machines of the second wave discovered and bombed it. However, they only achieved a single hit, which switched off some guns amidships, but otherwise caused little damage. However, the two destroyers were hit by several bombs destined for the Pennsylvania , the fragments of which perforated their hulls and ignited the oil leaking from their fuel tanks. The numerous fires and exploding ammunition caused severe damage to the hulls of the destroyers, the hulls were practically destroyed by the resulting structural damage. The fire also caused rather superficial damage to the bow of the Pennsylvania . Half of the dock was flooded during the attack, which should prevent damage from incoming water in the event that the outer gate of the dock was destroyed. The Cassin partially floated up and tipped against the Downes side . The destroyer Shaw , lying in a floating dock nearby , was hit three times in the forecastle. The resulting fires could not be controlled, so that half an hour later the front magazines of the destroyer detonated. As a result of the explosion, the floating dock was sunk, and the Shaw also lost its entire bow, the debris of which flew up to 800 meters.

Other bombers of the second wave occasionally attacked different ships in the harbor, so the Raleigh and the Curtiss were each hit by a bomb. The airfields were also bombed again. Around 9:45 a.m., the last Japanese planes turned off and returned to their aircraft carriers. One of the last machines to land at 1:00 p.m. was Frigate Captain Fuchida, who had stayed over Pearl Harbor during the entire attack to observe the damage. After hearing his initial assessment, Admiral Nagumo ordered the withdrawal without further attack at 1:30 p.m.

American scouts who started after the attack looked north for the Japanese unit, but could not find it because it was much further north than assumed. It was then assumed that the observed arrival and departure of the Japanese from the north was just a feint and that the Japanese porters were west or south of Hawaii.

Responsible for this misjudgment were the ranges of the Japanese carrier aircraft, which were still unknown at the time and which far exceeded that of their American counterparts. While the Japanese Kate , Val and Zero had ranges of over 1,500 km, the American dive bomber SBD Dauntless had a range of 1,200 km, the torpedo bomber TBD Devastator , equipped with a torpedo, even managed only 700 km (1,150 km with a 453 kg bomb ). The pure flight distance for a return flight to Pearl Harbor from the starting point 400 km away was already 800 km. In addition, most of the machines first flew in a circle after take-off while they formed themselves over the girders and waited for the remaining machines. Additional fuel was also consumed during the landing, as only one aircraft could land at a time and the others had to wait correspondingly long. In the Battle of Midway , the American porters only started their machines after they had approached their destination within 200 km. It was hard to imagine that the Japanese could take off from twice the distance, which is why the American scouts turned off too early. In the months that followed, this misjudgment of the range led the Allies repeatedly to the wrong assumption that Japanese aircraft carriers would have to be nearby if Japanese aircraft of these types were sighted at locations which the Allied commanders firmly believed were beyond the range of Japanese airfields lay.

Nagumo's decision to withdraw

According to the original plan, the first two waves of attack should have been followed by at least one more to destroy the shipyard facilities and fuel tanks. The loss of these facilities and supplies would have severely restricted US Forces operations in the Pacific in the months that followed. Given the course of the war, many historians believe that the shutdown of Pearl Harbor as a naval base would have been a far more serious loss to the United States than the shutdown of the battleships. Nevertheless, Admiral Nagumo decided not to start the third wave, but to withdraw as soon as the attack formations returned. He gave the following reasons for his decision:

- The reports received from the first and second wave of attacks left no doubt that the battleships moored in Pearl Harbor had been devastated. Without these ships, the US fleet, even with massive reinforcements from ships from the Atlantic, was unable to seriously hinder the major Japanese offensive in Southeast Asia that was being launched at the same time. The main strategic goal of the attack was thus achieved.

- Preparing a third wave would have taken a considerable amount of time. The machines of the first wave were brought below deck immediately after landing, since the flight decks had to be free for the landing of the second wave. The re-equipment with bombs and fuel would have required additional time, then the machines had to be brought back to the flight deck to start, while at the same time the machines that had landed on the flight deck had to be brought into the hangar deck. This complex and time consuming process would have meant that the third wave would not have returned before dark. Night landings on carriers were not common in 1941, there were no safe procedures for landing in the dark, and the carrier machines were mostly not suitable for night flight. A night landing would most likely have meant the loss of many experienced pilots that Japan could not do without. In addition, the ships would have been extremely vulnerable during the refitting of the aircraft. Six months later, the aircraft carriers Akagi , Sōryū , Hiryū and Kaga were destroyed in the Battle of Midway by a relatively weak attack that happened to occur during their preparations for launch.

- The losses of the second wave were twice as high as those of the first, since it attacked without any element of surprise. Due to the break of several hours, another attack would fly against a fully prepared enemy and suffer even higher losses.

- As long as the machines were in motion, Nagumo had to remain in his position so that they could find him to land. However, this would give American forces the opportunity to counter-strike with any remaining bombers and their submarines. Although the Japanese squadrons had been flying to the island from all directions as a deception, he had to reckon with the fact that the Americans had noticed from which direction the planes were flying in and out.

- The aircraft carriers were needed for the offensive in Southeast Asia. Many of the destinations in Indonesia and New Guinea were beyond the reach of land-based aircraft. He was not allowed to expose his associations (porters and their aircraft) to great risk if there was no compelling reason to do so. In his opinion, the destruction of the Pearl Harbor base was not enough.

- The US aircraft carriers were not in Pearl Harbor and so there was a risk that they would suddenly strike the Japanese fleet. If the Japanese aircraft were over Pearl Harbor at this point in time, the Japanese carriers would be almost defenseless against the attacks of the US carrier aircraft.

Several staff officers and squadron commanders from the first wave of attacks that had returned urged him to carry out the third attack, but they could not change his mind.

Balance sheet

losses

The immediate results of the attack have been assessed inconsistently. This is because smaller ships were often not counted or there were inconsistencies in the counting of damaged or destroyed ships. Some of the dead and wounded were recorded separately according to civilians, navy and army affiliation, in some balance sheets the civilian victims were not recorded at all.

The following summary shows only roughly the destruction and the number of victims in Pearl Harbor.

Losses on the US side

- 2403 dead

- 1178 wounded

- 18 ships were sunk or - some seriously - damaged.

- 9 damaged ships

- 188 aircraft destroyed

- 159 damaged aircraft

Ultimately, with the exception of 3 ships (the Arizona, the Oklahoma and the Utah) all sunk or badly damaged American units were lifted again and used again during World War II. Along with the Mississippi, five of the battleships sunk or damaged in Pearl Harbor ( Maryland , West Virginia , Tennessee , California and Pennsylvania ) fought the Battle of the Surigao Strait in 1944 . In this final battle between battleship fleets, fought by battleships from the First World War and not the more modern Iowas and Yamatos , they sank the Japanese battleships Yamashiro and Fuso . The Nevada sailed towards Normandy in 1944 as part of the Allied invasion fleet.

The worst loss for the United States was the deaths of many innocent people. Of the 2,403 dead in 2008, were Navy, 109 Marine Corps and 218 Army. 78 civilians were among the dead. In addition there were 1,178 wounded. Arizona , which was almost completely destroyed by the magazine explosion, is now a memorial; the wreck of the old battleship Utah , which was converted into an anti-aircraft training ship , was merely pulled into a position where it is out of the way. The last ship to be lifted was the capsized Oklahoma in 1943 , and the lengthy repair of its massive structural damage was no longer worthwhile at this point.

Medal of Honor awards

15 soldiers were honored for their behavior during the attack with the Medal of Honor , the highest honor of the US armed forces, 10 of them posthumously .

- Captain Mervyn Sharp Bennion , commandant of the battleship USS West Virginia (BB-48) , posthumously

- Lieutenant John William Finn , part of the Kāneʻohe Bay Naval Air Base Repair Force

- Ensign Francis Charles Flaherty , crew member of the battleship USS Oklahoma (BB-37) , posthumously

- Rear Adm. Samuel Glenn Fuqua , crew member of the battleship USS Arizona (BB-39)

- Chief Boatswain Edwin Joseph Hill , crew member of the battleship USS Nevada (BB-36) , posthumously

- Ensign Herbert Charpiot Jones , crew member of the battleship USS California (BB-44) , posthumously

- Rear Admiral Isaac Campbell Kidd , 1st Battleship Division commander, posthumously

- Lieutenant Commander Jackson Charles Pharris , crew member of the battleship USS California (BB-44)

- Chief Radioman Thomas James Reeves , crew member of the battleship USS California (BB-44), posthumously

- Captain Donald Kirby Ross , crew member of the battleship USS Nevada (BB-36)

- Machinist's Mate First Class Robert Raymond Scott , crew member of the battleship USS California (BB-44), posthumously

- Chief Watertender Petar Herceg Tomich , crew member of the battleship USS Utah (BB-31) , posthumously

- Captain Franklin Van Valkenburgh , commandant of the battleship USS Arizona (BB-39), posthumously

- Seaman First Class James Richard Ward , crew member of the battleship USS Oklahoma (BB-37), posthumously

- Captain Cassin Young , commander of the workshop ship USS Vestal (AR-4)

Losses on the Japanese side

- about 65 pilots and submarine crew members killed,

- about 29 destroyed aircraft,

- about 5 sunk two-man submarines,

- 1 prisoner (submarine commander Lieutenant Sakamaki Kazuo ).

The low Japanese casualties of just 29 aircraft exceeded even the most optimistic predictions of the attack's planners. Far higher losses were expected. That this did not happen was due both to the complete surprise achieved and the lack of combat readiness in which the American armed forces were before the attack.

Strategic Impact

At the same time as the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese offensive began in the Pacific, Japanese troops marched into Thailand and landed in the Philippines . On the morning of 10 December Malay local time (just under 48 hours after the attack), Japanese bombers with the Prince of Wales and the Repulse sank battleships on the high seas and in full combat readiness for the first time in history . The sinking of these fast and modern ships by air forces alone ended the previously dominant role of the battleship in naval warfare.

With only one battleship left, the Colorado not moored in Pearl Harbor , the American Pacific Fleet was no longer a threat, allowing Japan to deploy its entire fleet in Southeast Asia. Due to its now enormous superiority at sea and in the air, it had the unrestricted initiative in the combat area, which enabled the Japanese to defeat the nominally equally strong Allied ABDA forces (both sides had about eleven divisions of land forces in the combat area ) within three months overrun without major difficulties.

The American Pacific Fleet was left with only the defensive after the attack. Offensive operations were out of the question for a long time, as the Japanese fleet was now superior in every respect. It was possible to repair the slightly damaged battleships Maryland , Tennessee and Pennsylvania within three months in day and night work, which together with the Colorado and the Idaho , Mississippi and New Mexico , which had been relocated back from the Atlantic , had seven battleships available again. With that, however, one was clearly inferior to the eleven Japanese battleships , which had been reinforced by the Yamato .

With the aircraft carriers, the balance of power was even more unfavorable. Although no porter had been lost and reinforcements were received from Yorktown and Hornet , the five American porters were opposed to eleven Japanese. The qualitative difference in this now extremely important branch of arms weighed considerably more heavily than the numerical inferiority. The Japanese had extensive experience in carrier operations, their teams were perfectly trained, and their pilots had gained combat experience through China over the past four years. On the American side, larger carrier operations were nothing new, as attacks by aircraft carriers on the Panama Canal had been practiced and evaluated in pre-war maneuvers . However, since the US carriers had been equipped with new aircraft types in the meantime, there were initially problems with coordinating the activities on the flight deck. When the carriers Enterprise and Hornet were supposed to launch all machines in a joint attack six months later in the Battle of Midway , it took too long after the first half of the machines had started to get the second half ready to go. One was forced to give up the joint attack and send off the aircraft that had already taken off on their own before they lost too much fuel while waiting. As a result, the units attacking now without hunting protection suffered heavy losses. More serious, however, was the lack of technical equipment, especially in the case of fighters and torpedo weapons. The Grumman F4F was far inferior to the Mitsubishi A6M in maneuverability, climbing power and speed and it was not until mid-1943 that suitable aircraft types ( Grumman F6F and Vought F4U ) were available. However, the new aerial combat tactics developed by John S. “Jimmy” Thach gave the US pilots real chances of aerial victories against the Japanese types even with the older machines. As for torpedo aircraft, the Douglas TBD was hopelessly out of date. Although it was replaced by the Grumman TBF after the Battle of Midway , the torpedoes themselves were slow and rarely worked. In order to save money, only a few tests had been carried out before the war, so that no effective torpedoes were available until 1943. The performance of the Japanese long-lance torpedo was never matched.

Since there was nothing left for the surface fleet for the foreseeable future but to try to hold the position as best it could until new ships came from the shipyards, the submarines became the only weapon that can be used offensively against Japan could. Chester W. Nimitz , one of the few admirals who emerged from the submarine weapon, was therefore appointed as the new commander of the Pacific Fleet . In the following years, the American submarines waged a tonnage war against Japan , which was dependent on its sea connections , which was so successful that it is now regarded by all sides as one of the main causes of the American victory in the Pacific.

The Japanese high command regarded the battle as a strategic success that exceeded its wildest expectations. The Japanese fleet had operated at the limit of their range, surprised the enemy to an extent that was hardly thought possible, and eliminated its entire battle fleet in one fell swoop. Given the unexpectedly low own losses of only 29 machines, the absence of the aircraft carriers and the sparing of the docks and oil depots appeared to be minor blemishes in an otherwise incredibly perfect Japanese victory.

Today, however, the attack is viewed as a complete strategic failure on all counts. The fact that they did not sink an aircraft carrier was still excusable, since the Japanese high command could neither foresee nor react to their absence when the consulate learned of Lexington's departure on December 5th. The attack could only be carried out on December 7th, the Japanese task force had no fuel reserves that would have allowed the attack to be postponed, let alone that the entire offensive in Southeast Asia could be stopped for a short time. The fact that Nagumo failed to attack and destroy the base and its facilities was very detrimental to the Japanese. Losing the only docks in the Central Pacific would undoubtedly have hit the US hardest. The fact that this did not happen shows that the priorities were wrongly set both by Nagumo itself and by the high command, which later saw the decision to break off the attack as correct.

The extent to which the termination of the attack without a third wave of attacks is to be assessed as a misjudgment of the situation is sometimes controversial. It is true that the assumption that the destruction of the docks and fuel tanks would have hindered the US considerably in its strategic planning and would probably have forced it to retreat to the US west coast is correct. However, this is offset by the fact that the Japanese armed forces in the attack fleet lacked the tactical means to successfully attack a large naval base. Due to the composition of the available carrier-based air forces, there would have been a high probability of only an attack with dive bombers, which had already suffered the greatest losses in the first two attack waves (14 dive bombers were lost in the second attack wave alone, 41 were damaged ). The success of a third wave of attacks must therefore be questioned, as the air defense in Pearl Harbor had quickly recovered. In addition, it would only have been possible to arm the attack aircraft with 250 kilogram bombs, which made effective strikes even more difficult. The effects of the attack by carrier aircraft on a secured and prepared base became apparent a few months later with the attack on Midway.

The attack on the battleships is also often criticized: since they sank in the shallow harbor water, they were relatively easy to lift and repair. If Japan had waited according to the original war plan (valid before the relocation of the fleet from San Diego to Pearl Harbor) for the fleet to leave to reinforce the attacked Philippines and then sunk the battleships on the high seas, they would have been permanently lost. In addition, the sunk battleships turned out to be unsuitable for the battleship's new role as aircraft carrier escort due to their low speed and mainly supported amphibious landings with their artillery during the war . In addition to the loss of material on the high seas, there would have been a far higher number of human losses that would have had to be replaced. The situation after Pearl Harbor was different: many sailors and specialists were still available after the attack and were practically ready for action. In addition to these considerations, there is ultimately another fact: the sinking of the older battleships meant that the United States ultimately only had to concentrate on building aircraft carriers to stand up to the Japanese Navy. In this way, Pearl Harbor has accelerated the paradigm shift in marine strategy. During the war, the United States put 18 large fleet carriers and 77 escort carriers into service.

In conclusion, it must be stated in this context that the attack on Pearl Harbor - as severe as it may have been - was not only a strategic failure for the Japanese Empire, but actually already marked the course of the war. One of the biggest mistakes, in the eyes of some authors, was the fact that Japan got involved in the war with the US and its potential without developing an exact strategy how this conflict should lead to the desired result, and this negligence in the USA as well could not revise the following war years.

Political Impact

The most serious consequence was the effect of the attack on public opinion in the USA: isolationism and pacifism suddenly lost their influence. On December 8, the United States officially declared war on Japan; the declaration of war was passed with only one vote against in the Congress , which had previously been split between isolationists and interventionists . Four days later, Germany and Italy, who had also been surprised by the attack, declared war on the US, with the US officially entering the European part of the war.

The surprise attack was considered insidious and perfidious in the USA because it came as a complete surprise to the people of the USA without a prior declaration of war (the note that was handed over late on December 7th only contained the termination of negotiations). In the United States, the term Pearl Harbor has since been used as a metaphor for a devastating, unprovoked, and unforeseen attack. December 7, 1941 is often referred to as the Day of Infamy , after opening , with which he obtained the approval of the declaration of war from Congress the next day. The desire for vengeance and victory over Japan meant that the armed forces' recruitment offices were crowded with volunteers. Japanese-born Americans were the first to feel the hatred; they were the victims of numerous attacks and ultimately imprisoned in internment camps. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan apologized on behalf of the US government for this "racism, prejudice and war hysteria" based behavior.