Japanese invasion of Sumatra

| date | February 14 to March 28, 1942 |

|---|---|

| place | Sumatra |

| output | Japanese victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

West Sumatra: JHM Blogg |

|

| losses | |

|

? |

? |

1. Borneo - Manado - Tarakan - Balikpapan - Ambon - Makassar - Sumatra - Palembang - Badung - Timor - USS Langley - 1. Java Sea - Sunda Strait - Java - 2. Java Sea - U 168 - U 537 - U 183 - Ashigara - 2. Borneo

1941

Thailand - Malay Peninsula - Pearl Harbor - Hong Kong - Philippines - Guam - Wake - Force Z - Borneo

1942

Burma - Rabaul - Singapore - Sumatra - Timor - Australia - Java - Salamaua - Lae - Indian Ocean - Port Moresby - Coral Sea - Midway - North America - Buna-Gona - Kokoda-Track

The Japanese invasion of Sumatra took place from February 14th to March 28th 1942 as part of the Pacific War in Southeast Asia and led to the fall of the entire colonial possessions of the Dutch on the island. The fall of Sumatra was planned before the invasion of Java in order to eliminate the strong western flank of the Allies with access to Java .

prehistory

After the Japanese successfully conquered the Malay Peninsula from north to south (→ Japanese invasion of the Malay Peninsula ), the Allies began to move troops to Sumatra in December 1941 . First British and Australian bomber squadrons were relocated to the south of the island, as they suffered too great losses on the Malay Peninsula. Furthermore, a convoy of ships brought around 3,400 Australian soldiers to Sumatra.

At a staff conference on December 16, the Allies decided to ask the Dutch to reinforce their troops in Sumatra and Java. Plans were also drawn up to set up replenishment camps in Sabang , Medan and Pekanbaru . However, these were withdrawn on December 27th in order to station a ready-to-use bomber squadron on the two airfields P1 ( Pangkalanbenteng ) and P2 ( Praboemoelih ) near Palembang , which had been chosen as the location of the new headquarters . P2 had not yet been discovered by the Japanese during their reconnaissance flights. Since the airfields were not in good condition, the expansion began on December 31; available ground crew arrived in early January. Another airfield was to be created near Oosthaven , today's Panjang port of Bandar Lampung . Work on the runways also started at Medan and Pakan Baroe. Since there were no anti-aircraft guns , ABDACOM had six heavy and six light Bofors flak delivered to the two Palembang airfields. Another eight anti-aircraft guns were set up on the refineries. However, there was an ammunition problem, as the ships carrying the ammunition had been sunk by the Japanese during the crossing.

Operation "L"

The first Japanese air strike came on February 6 and hit the P1 airfield near Palembang. The Allies lost two Blenheim bombers and four Hurricanes . Two more hurricanes were damaged. On the ground, the Japanese managed to destroy two Buffalos . In the attack, the Allies could only shoot down a single Japanese Nakajima Ki-43 . In return, the Allies launched night raids against the Japanese lines on the Malay Peninsula and flew air raids for the refugee convoys from Singapore .

The Japanese Army had moved the 229th Infantry Regiment of the 38th Infantry Division from Hong Kong to Cam Ranh Bay in Indochina for Operation "L" . From there, on February 9, 1942, 8 transporters, accompanied by a cruiser , four destroyers , five minesweepers and two submarine hunters under the command of Rear Admiral Hashimoto Shintaro , set sail to bring an advance guard to Bangka and Palembang. Rear Admiral Ozawa Jisaburō followed the next day with the western cover fleet on the cruiser Chōkai with five other cruisers, the aircraft carrier Ryūjō and four destroyers. The main force followed on February 11 in 13 transports, which were accompanied by a heavy cruiser, a frigate, four destroyers and a submarine hunter.

There were four Dutch submarines at the Anambas Islands , but these could not reach the Japanese fleet. The vans and cargo ships that ran out of Singapore and were traveling with refugees on their way east towards Java and south towards Sumatra were attacked by Japanese planes belonging to the Ryūjō . In doing so, they damaged the British light cruiser HMS Durban , which had to turn off for Colombo . Shortly after more refugee ships and tankers had joined the convoy, the Japanese repeatedly attacked with Ryūjō aircraft and also with land-based bombers from the Genzan air unit. Two tankers, a steamer and many smaller units were sunk, and another tanker and two transporters were badly damaged.

At 8:00 a.m. on February 14, the reconnaissance corps near Palembang warned of a large wave of Japanese attacks approaching the city. At that time, all available own forces were on escort flights with the convoys at sea and were not within radio range . First a Japanese bomber squadron flew over the airfield P1 and unloaded its load. The escort hunters then raked the area with machine gun fire. Immediately afterwards, 260 Japanese paratroopers from the 1st Japanese Airborne Division landed at P1. They came from the captured Kahang airfield in Malaysia . A second wave of 100 paratroopers coming from Kluang landed shortly afterwards a few kilometers west of P1 at a refinery.

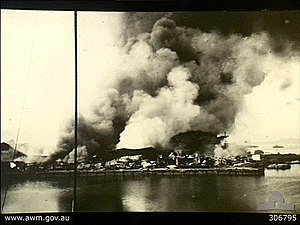

Only 150 British flak crews, 110 Dutch soldiers and 75 British ground defense men were available for defense on P1. While the Japanese piled vehicles up to roadblocks and ignited smaller firefights with the defenders, some service men managed to refuel aircraft that had landed. The machines immediately flew to the previously undiscovered P2 airfield. Headquarters should also move to P2 after reports from the refinery and from Palembang itself. In the afternoon there was a stalemate. The British still held the airfield, but their ammunition was running low and they were hampered by the road blockade. After a false report of further Japanese parachute landings spread about 25 kilometers away, the British commander HG Maguire decided to evacuate the airfield and the city. At the refinery, the Japanese used air raid shelters as their own positions, which were doggedly defended. The following day, another 100 Japanese landed at the refinery. After a fierce battle that lasted all day, the defenders were able to push the Japanese back, but the refinery was badly damaged by machine gun fire and was on fire. On the other hand, surrounding other smaller systems were only slightly damaged and were able to resume operation shortly afterwards. However, they were prepared for demolition in case the Japanese could not be stopped.

Meanwhile, the escort fleet under Vice Admiral Ozawa had swarmed north of Bangka to form an extensive cover for the Japanese landings that took place shortly afterwards. A vanguard went ashore on Bangka while the main units in the Palembang area had arrived at the mouth of the Musi River and were advancing towards the city by water. A defense at the mouth had not been set up by the Dutch because it was considered useless against the artillery fire of the ships expected from the sea.

At this time, Japanese scouts sighted the incoming ABDA fleet under Rear Admiral Karel Doorman in Gasperstrasse on a north course. On Wavell's orders , Doorman had collected the fleet, consisting of the Dutch cruisers De Ruyter , Java and Tromp as well as the British cruiser HMS Exeter and the light Australian cruiser HMAS Hobart with ten destroyers, south of Bali and set out for Sumatra on February 14 . Japanese warplanes from the Ryūjō and Malaysia attacked the ABDA force at noon the next day, forcing Doorman to withdraw all of his ships south.

The landing fleet in Bangka Street had also been spotted by British reconnaissance planes that had taken off from P2. In the early morning, 22 Hurricanes, 35 Blenheims and 3 Hudsons attempted to attack the ships. However, they were involved in fierce dogfights by Japanese aircraft. After the news about the Japanese parachute landing at P1 became known on P2, the commander initiated preparations for an evacuation of the airfield. The later message that P1 had not yet been surrendered resulted in the returned machines being prepared for a new attack that night. In the morning mist, the Allied warplanes flew violent attacks against the Japanese, who had just started landing at the mouth of the Musi. Japanese aircraft withdrew shortly after the start of the battle, so that the Allies managed to hit the transporters directly. Twenty landing craft were sunk and hundreds of Japanese people were killed. The last Allied successes were achieved by Hurricanes when they attacked and destroyed unprotected landing craft on the southwest beach of Bangka.

In the meantime, the Dutch commandant's office had issued the order to destroy the oil and rubber bearings. The ferries across the Musi should be destroyed within the next hour to make it difficult for the Japanese to translate. The defenders of P1 were thus forced to retreat quickly. On the night of February 15, Japanese units that had survived the air strike in the Musi Estuary reached Palembang and shocked the paratroopers who had landed at P1 and the refinery.

On the morning of February 15, Wavell ordered an orderly retreat to embark its own troops to Oosthaven, where a number of small ships were moored in port. There, 2,500 British RAF members, 1,890 British infantrymen, 700 Dutch soldiers and around 1,000 civilians were evacuated by means of twelve ships on February 17th. An Australian corvette covered the retreat and destroyed port facilities and oil tanks. A smaller steamer was anchored a little longer in the harbor in order to be able to take in refugees arriving later.

In the meantime the Japanese had completely taken Palembang and destroyed the oil refineries except for two smaller stations. Small troop carriers drove up the river to Menggala .

All remaining airworthy Allied warplanes were flown out on February 16. The airfield personnel went to India by sea . Since the Japanese did not advance to Oosthaven for the time being, another task force went ashore there on February 20 to save spare parts for aircraft and to destroy the other usable facilities.

On February 24th, the Japanese reached Gelumbang .

Operation "T"

The allied units remaining on Sumatra, mainly KNIL members, withdrew to the central and northern provinces of the island. From there, the Dutch planned to recapture Palembang and expel the Japanese from the island. But the Japanese hardly gave them time to regroup their troops. They sent a 750-man motorized reconnaissance unit northwards, which quickly advanced to the two Dutch companies, consisting of about 350 soldiers under Major CF Hazenberg . These could only oppose the Japanese in small defensive battles, but hardly hinder their advance. After almost three weeks, the Japanese reached Moearatebo on March 2nd . A relief unit of the Dutch from Padangpadjang was able to advance there because the heavy rain that set in made it much more difficult for the Japanese to cross the river. Fire fighting broke out on the following days when the Japanese tried to cross the river. Dutch scouts reported many dead on the Japanese side and that only about 200 soldiers were still ready for action. Therefore, Hazenberg decided on the night of March 9th to launch a counterattack. The day before, the Dutch loaded many collected local boats out of sight of Japan with ammunition and other supplies and the attacking troops were formed. But after the news of the surrender on Java arrived on March 8, all offensive efforts had to be broken off at the behest of the top leadership. It was decided, as Sumatra was dependent on the supplies from Java, to take a defensive course. West Sumatra was to be left to the Japanese and only a small part of the north was to be held with the forces still available for as long as possible until an evacuation by sea could be organized.

During the retreat, the KNIL units destroyed all airfields and port facilities. They withdrew to fortified positions at the south entrance of Alice Valley, where they planned to hold off the Japanese as long as possible. Should the positions fall, a guerrilla war from the surrounding area was planned. However, this undertaking would prove to be difficult, since the population of Sumatra did not cover their backs for the Dutch as a long-standing colonial power, but on the contrary would betray the positions of the Dutch to the Japanese. This was particularly evident when the Dutch tried to move around 3,000 Europeans and Christian civilians from the coast to refugee camps inland in the province of Aceh . A Muslim uprising that broke out shortly after the Japanese landings began, stopped the action.

The Japanese "Operation T" began on February 28th when 27 transporters with 22,000 soldiers of the Imperial Guard on board left Singapore. They were divided into four convoys and were accompanied by three cruisers, ten destroyers, patrol boats and anti-submarine units. Since the Allied air and sea defense was de facto deactivated at this point, they reached North Sumatra completely unmolested.

On March 12, they occupied Sabang and Koetaradja without encountering any resistance. Meanwhile, the domestic troops were able to conquer the city of Medan with the strategically important airfield. Idi to take the Langsa and Pangkalanbrandan oil fields followed the next day. The Japanese also went ashore at Laboehanroekoe .

Sumatra fell on March 28th when Dutch Major General RT Overakker and 2,000 soldiers surrendered near Kutatjane in North Sumatra . Many Allied prisoners were forced by the Japanese to build the railway line between Pekanbaru and Moera . (Overakker himself was shot together with other officers of the KNIL in view of the looming defeat of the Japanese of them in 1945 as a prisoner of war.)

literature

- Tom Womack, Dutch Naval Air Force Against Japan: The Defense of the Netherlands East Indies, 1941-1942 , McFarland & Company, 2006, ISBN 0-7864-2365-X

- Nicholas Tarling, A Sudden Rampage: The Japanese Occupation of South East Asia , C. Hurst & Co, 2001, ISBN 1-85065-584-7

Single sources

- ↑ a b L Klemen: Major-General Roelof T. Overakker . In: Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942 . 1999-2000. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ↑ The Sumatra “Death Railway” . In: COFEPOW . Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved July 23, 2011.