Battle for Midway

| date | 4. bis 7. June 1942 |

|---|---|

| place | Midway Islands |

| output | American victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 3 aircraft carriers 50 more ships |

4 aircraft carriers 150 other ships |

| losses | |

|

1 aircraft carrier |

4 aircraft carriers |

1941

Thailand - Malay Peninsula - Pearl Harbor - Hong Kong - Philippines - Guam - Wake - Force Z - Borneo

1942

Burma - Rabaul - Singapore - Sumatra - Timor - Australia - Java - Salamaua - Lae - Indian Ocean - Port Moresby - Coral Sea - Midway - North America - Buna-Gona - Kokoda-Track

The Battle of Midway was a naval battle during the Pacific War in World War II . From June 4 to 7, 1942, large units of the Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States Navy fought at the Midway Islands . The battle, which ended with the sinking of four Japanese aircraft carriers and only one sunk US carrier, is considered the turning point of the Pacific War. From then on, the Japanese armed forces were on the defensive.

Triggering factors

Since Japan attacked the Western Allies in December 1941, its forces have carried out an extremely successful campaign to conquer the British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia . When the operations to conquer the resource-rich areas in Malaysia and the Dutch East Indies neared their end in the spring of 1942, the Japanese high command discussed how to proceed. A faction of the Japanese military wanted to advance further west in the direction of India and Suez and finally establish contact with the German Africa Corps . Another faction, on the other hand, favored an advance towards Fiji - Samoa in order to break the Allied lines of communication between Australia and the USA .

With the American air raid on Tokyo ( Doolittle Raid ) on April 18, 1942, however, the Japanese plans changed. Up until then, the U.S. Pacific fleet, weakened after the attack on Pearl Harbor , had not appeared to be a serious threat, and since there were no targets in the Central Pacific to conquer, the Japanese had not been further into it since the conquests of Wake and Guam Advance territory. After the attack on Tokyo, Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku made the destruction of the remaining US fleet - especially its aircraft carriers - a top priority. This should not only make further attacks against Japan impossible, but also rule out any conceivable threat from the Americans in the near future and perhaps even lead to a negotiated peace between Japan and the USA.

The Midway Islands are the most westerly of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands after the small Kure Atoll and at that time they were the westernmost outpost of the Americans in the Central Pacific. The islands themselves were of little strategic value; Due to their small size, they were only suitable as a reconnaissance base, but not as a larger base. However, they proved to be quite useful as a refueling station for the submarines operating from Pearl Harbor against Japan - the boats could thus remain in the area of operation for considerably longer, since the outward and return journeys between Pearl Harbor and Midway together make up over 3500 kilometers. Plans to capture Midway had existed on the part of the Japanese since the beginning of the war, but they had never been carried out because the effort to supply the conquered islands was considered greater than their use as a basis for reconnaissance.

However, due to its relative proximity to Pearl Harbor, the only port that could be used as a large naval base and which was available to US forces outside of the ports on the US west coast in the Pacific, the Americans could not afford to lose the island easily . An invasion of Midway provided the opportunity to force the US Pacific Fleet into a decisive battle despite its weakness.

The Japanese strategy

The plan was to take the two small atoll islands (Sand Island and Eastern Island) and build an air base there. This should induce the Americans to march their carrier fleet to Midway. The battle-hardened Japanese superiority wanted to attack them there and destroy as many enemy carriers as possible. As an ultimately unsuccessful diversionary maneuver, a strike against the Aleutians in the northern Pacific was planned (see Battle of the Aleutians ).

After a victory, the overwhelming power of the Japanese in the Pacific would have become so great that, according to the Japanese hope, a peace treaty could have been negotiated, which laid down the current borders - as envisaged in the Japanese strategy of final victory .

Starting position

After the Battle of the Coral Sea on May 7th and 8th, 1942, in which the American aircraft carrier USS Lexington was lost and the carrier USS Yorktown was badly damaged, the Japanese waited and waited. The leadership of the American Navy suspected that the enemy was gathering his strength to prepare for the invasion of Australia . Another possible destination was Port Moresby , New Guinea . The longer the Japanese fleet remained hidden, the more suspected an impending attack on the naval base in Pearl Harbor became . As a next target, the Midway Atoll seemed plausible as a starting point for further attacks by the Japanese. The Japanese, on the other hand, assumed that the US was already tired of the war.

Radio reconnaissance

A major factor in the run-up to the Battle of Midway was the decryption of the Japanese JN-25 naval code book and the combined radio reconnaissance of American, British, Australian and Dutch forces. Mention should be made of the stations HYPO in Hawaii and CAST in the Philippines, the group OP-20-G in Washington, the British stations in Hong Kong and Singapore, the group in Bletchley Park as well as Dutch forces in the East Indian Batavia . The posts that took over the interception and forwarding of the messages remain unnamed. In the literature, the work of Joseph Rochefort is often emphasized with regard to the Midway codes , who finally worked 36-hour shifts in a bathrobe, while the decisive ideas for determining the position of Midway came from Jasper Holmes.

The US radio reconnaissance OP-20-G received a message a few days after the Coral Sea Battle, which was addressed to all major Japanese aircraft carriers and which was similar to an operational order. Shortly afterwards, another radio message was sent to the Goshu Maru , in which there was talk of an AF destination code . The Americans knew that such abbreviations were used for various targets in the Pacific region. For example, RZP stood for Port Moresby , R for Rabaul , PS for Saipan and AH for Oʻahu . Since some of the A-abbreviations referred to Hawaii and the surrounding islands, some radio reconnaissance planes suspected Midway to be AF .

The American radio operators on Corregidor Island in Manila Bay had already identified AF as Midway in March , but the Japanese occupation of the Philippines meant they were no longer in contact with them. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz quickly decided on Midway and had Admiral Ernest J. King , who initially thought of the Aleutians as a target, informed about the planned Japanese attack on May 18 .

The Americans used a ruse to protect the radio abbreviation AF . Via the submarine cable laid to Midway , the station there was instructed to send a radio message in plain text (unencrypted) to the high command stating that the distillation system for drinking water production was defective and that one would soon suffer from a lack of water. The high command then radioed back in plain text that water supplies would remedy the situation. Now it was up to the Japanese to determine whether they had listened to the radio messages and how they would react to them. Shortly thereafter, Tokyo sent the daily intelligence report to all ships. One of the messages was that AF was running out of water. This clearly identified Midway, and Nimitz immediately ordered all porters back to Pearl Harbor.

Towards the end of May, the Americans were able to identify the planned day of the attack using radio messages from the Japanese. It was scheduled for June 4th. On May 28, the Japanese changed the coding of their radio communications, so that no further messages could be decoded for the time being.

Prevention of the Japanese reconnaissance

The Japanese Operation K took place in March . During this operation, two Kawanishi H8K 1 flying boats were launched from Kwajalein to the Marshall Islands. The flying boats had then dropped bombs on Oahu and flown to the French Frigate Shoals . This atoll is exactly between Hawaii and Midway. There the flying boats were refueled by submarines. The US military was impressed by the enormous long-range performance of the flying boats in these ultimately useless attacks, but it was now other factors that brought these very powerful flying boats into the sights of US strategists. The US Navy rightly suspected that this game would be repeated with the aim of clearing the American fleet through the Kawanishi H8K flying boats. Therefore, a US flying boat was placed near the atoll. The US flying boat also promptly identified three Japanese submarine periscopes . The US flying boat was protected from the Japanese submarines by the coral belt. The Japanese had to forego the actually planned reconnaissance flights of the H8K1 flying boats and thus could not get an idea of the actual strength of the inferior US forces. However, the Japanese did not rate this as a great loss, since they had multiple superiorities in each case, they also had greater experience and their crews were also better trained and battle-tested.

Fleet movement

The Japanese set the carrier battle group Kidō Butai of Vice Admiral Nagumo Chūichi with four aircraft carriers, the flagship Akagi , the Kaga , the Hiryū and the Sōryū , in the direction of Midway. A few hundred miles behind came the battleships of Admiral in Chief Yamamoto Isoroku . The third Japanese wave under Vice Admiral Kondō Nobutake was approaching from the southwest . With his destroyers and cruisers , he formed the invasion fleet for Midway. However, Yamamoto was missing two of his aircraft carriers that he urgently needed before Midway: The carrier Shōkaku had been badly damaged in the battle in the Coral Sea, while the Zuikaku had lost a large part of its airborne squadron. Two other porters ( Junyo and Ryūjō ) had been detached to attack the strategically worthless Aleutians to support a diversionary attack . Yamamoto was only able to launch the attack on Midway with four large porters.

Admiral Nimitz cleared his fleet, consisting of the two aircraft carriers Enterprise (Capt. Murray ) and Hornet (Capt. Mitscher ) and waited for the Japanese. The Yorktown (Capt. Buckmaster ) was badly damaged in the Coral Sea and entered a dry dock in Pearl Harbor on May 27 for repairs. An initial assessment of the damage to Yorktown indicated that it would take three months to repair the damage.

However, since the ship was urgently needed for the defense of Midway, work on all other ships lying in the shipyard was temporarily suspended and the freed personnel were sent to Yorktown ; 2000 shipyard workers then worked non-stop day and night shifts. In addition, the work processes have been drastically simplified. For example, steel plates that had been shot were not replaced by new ones, but only the bent parts were cut out with cutting torches and the holes were "covered" with steel found at the shipyard. On May 29th at 9 a.m., only two days later and not after the estimated three months, the Yorktown was operational again. She ran after the two leading carriers , now as the flagship of Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, the commander of Task Force 17. In addition, Midway's air and land defense has been significantly upgraded.

Reconnaissance flights and first contact

In order to successfully counter the attack, Nimitz sent the combat groups TF-16 (KAdm. Spruance , Enterprise and Hornet ) and TF-17 (KAdm. Fletcher , Yorktown ) to a position 300 miles northeast of Midway. In addition, there were flying boats of the type PBY-5 / -5A "Catalina" as long-range reconnaissance aircraft , which scouted in a radius of 600 nautical miles around Midway.

On the morning of June 3, the American long-range scouts were again in the air. The first sighting was around 9:00 a.m. when two Japanese minesweepers were discovered about 470 miles west-southwest off Midway . Half an hour later, a PBY flying boat spotted the Japanese transport fleet heading east some 700 miles away. Later that day, American B-17s bombed the convoy but did no damage. In the afternoon, four PBY took off from Midway to attack the Japanese transport fleet that night. In the first hours of June 4th, the tanker Akebono Maru was hit with a torpedo . However, it was only slightly damaged and continued with the fleet.

The battle on June 4, 1942

The attack

Shortly after 5:30 a.m., a reconnaissance plane reported the sighting of the Japanese carrier fleet 320 kilometers (almost 200 miles ) northwest of Midway. A few minutes later, another machine was able to confirm this message and also report that the Japanese had launched more than 100 warplanes and bombers from their aircraft carriers in the direction of Midway. All preparations for the defense of the island were immediately made on the atoll . The American planes on Midway took off. The fleet units TF-16 and TF-17 had also heard the reports. However, these spoke of only two - instead of the expected four - aircraft carriers.

The following associations flew from Midway against the Japanese fleet:

- VMSB-241 (Major Lofton R. Henderson) with 16 SBD-2 "Dauntless" ( dive bombers )

- VMSB-241 (Major Benjamin W. Norris) with 11 SB2U-3 "Vindicator" (dive bombers)

- VT-8 Det. (Lt. Langdon K. Fiberling) with 6 TBF-1 "Avenger" ( torpedo bomber )

- 69th Bombardment Squadron / 3rd BG (M) (Capt. William F. Collins) with 4 B-26B "Marauder" - medium USAAF bombers , each carrying a torpedo

- 431st Bombardment Squadron (LtCol. Walter C. Sweeney) with 14 B-17E "Flying Fortress" - heavy bombers of the USAAF, which had started to attack the invasion fleet and were redirected

The fighter squadron VMF-221 (Maj. Floyd B. Parks) with 20 F2A-3 "Buffalo" and 5 F4F-3 "Wildcat" was not used to protect the bombers, but to protect Midways and caught the Japanese formation at 6:15 Clock off. The Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters who escorted the bombers inflicted considerable losses on the American fighter units. 17 fighters of the US Navy were shot down, only two machines were still airworthy after landing. One pilot remarked bitterly in relation to the unfavorable starting position of the surviving aerial combat: "Every commander must be aware that if he lets his pilots ascend in an F2A-3, they are lost before they leave the ground."

At 6:30 am, the Japanese combat group reached Midway and bombarded both islands for 20 minutes. Targets were hit on Eastern Island, but the runways remained almost undamaged. On Sand Island, oil tanks, the seaplane hangar and other buildings were destroyed. The commanding Japanese pilot Kaigun-Shōi Joichi Tomonaga reported because of the minor damage that a second wave was necessary to significantly weaken the American defense. Admiral Nagumo had half of his planes on deck for an attack against the US carrier fleet, if it should unexpectedly turn up. Since it had not yet been discovered, he ordered the conversion of the bombers from sea to land target bombs and from torpedoes to bombs.

While the Japanese machines were on their way back to their carriers, the American bombers from Midway attacked the enemy ships. Without fighter protection and with many inexperienced pilots, the losses of the Americans were high without being able to score a single hit. The first attack was the six land-based TBF Avenger torpedo bombers launched by Midway . Five out of six were shot down when this type of aircraft was in combat for the first time. They were followed by four B-26s - also coming from Midway - which dropped torpedoes. Two B-26s were shot down.

At the same time, a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft sighted the American fleet without first discovering the carriers. Vice Admiral Nagumo immediately stopped the retrofitting of the bomber planes.

16 SBD dive bombers followed, hitting nothing, but eight SBDs were lost. For most American pilots this was their first war mission. They had just received rash training. This was followed by an attack by 15 B-17 bombers from a height of 4000 m, which hit nothing. Now the eleven "Vindicators" from Midway reached the ships and attacked them unsuccessfully with bombs. You lost three machines.

Turning point

At 7:00 a.m., the carriers Hornet and Enterprise started their carrier squadrons. From the Enterprise, the VT-6 squadron started with 14 torpedo bombers ( TBD-1 “Devastator” ), VB-6 and VS-6 with 34 dive bombers (SBD “Dauntless”) and VF-6 with ten fighters (F4F-4 “Wildcat “) To attack the Japanese porters. From the Hornet , VT-8 started with 15 TBD-1, VB-8 and VS-8 with 34 SBD-3 and VF-8 with ten F4F-4. Soon after, beginning at 8:38 a.m., the Yorktown planes were also started, which were held back first in case the other two Japanese carriers still showed up. From there the VT-3 started with twelve TBD-1, VB-3 with 17 SBD-3 and VF-3 with six F4F-4. In total, the attack was flown by 84 SBD-3s, 41 TBD-1s and 26 F4F-4s.

There was uncertainty aboard the American carriers about the course the aircraft should take. For the 59 aircraft of the Hornet , Cmdr. Stanhope Ring a more northerly course. But the squadrons VB-8, VS-8 and VF-8 could not detect any Japanese. Only the 15 torpedo bombers (TBD) under Lt. Cmdr. John Waldron, who had ordered a more southerly course, was successful. They were the first to find the Japanese and were completely destroyed. Shortly afterwards the Enterprise torpedo bomber squadron arrived, ten of the 14 torpedo bombers were lost. The twelve torpedo bombers of Yorktown flew their attacks in association with the other squadrons, but this squadron also lost ten of twelve TBDs. At the same time, however, these loss-making attacks resulted in the Japanese fighter's parachute being pulled to a low altitude and the dive bombers arriving shortly thereafter having a free path.

The Enterprise bombers under Lt. Cmdr. Wade McClusky almost missed the enemy too. When only empty sea could be seen at the interception point, McClusky assumed that the Japanese could only have turned to the north - and not to the south, as Ring had assumed. So he decided to fly in that direction as well. Because of this decision, KAdm Spruance saw in McClusky "the outstanding hero of the Battle of Midway", whose actions "decided the fate of the American carrier associations and the armed forces on Midway". At around 10 a.m., McClusky saw the destroyer Arashi , who had given up the hunt for the American submarine Nautilus and was returning to Nagumo's task force. McClusky decided to follow the destroyer and a short time later saw the Japanese carrier association. The Yorktown squadrons, which started later, had correctly assessed the course of the Japanese and therefore arrived at the same time as McClusky's squadrons by chance.

Since the Japanese fighters fought the torpedo bombers of Yorktown and had pulled the fighter protection down to a low height for this purpose, the SBD dive bombers of the Enterprise and Yorktown were able to attack from a great height around 10:20 a.m. After not a single hit had previously been scored in seven uncoordinated attacks, three of the four Japanese aircraft carriers were hit hard within six minutes. The Akagi , the Kaga and the Sōryū failed completely and could no longer take part in the further battle. The Sōryū and the Kaga sank in the following hours, the Akagi was badly damaged and was given up burning. Japanese destroyers sank them with torpedoes at dawn the following day so that the former flagship would not fall into enemy hands.

The last great Japanese aircraft carrier was the Hiryū . In an effort to avoid the torpedo planes, she had strayed far from the rest of the formation and was therefore not discovered by the SBDs. A combat group of 18 dive bombers and six escort machines started from here at around 11 a.m., followed by a second group of ten torpedo bombers and six fighter planes about one and a half hours later . The destination was the porter Yorktown . The bombers hit Yorktown around noon , and the damage to the boiler systems forced the ship to stop temporarily. The Japanese reported that they left the porter as a smoking and motionless wreck. However, the Americans succeeded in extinguishing the fire and at least partially putting the machinery back into operation. The flight deck could also be cleared again. At 2:45 p.m., the Japanese torpedo bombers accidentally hit Yorktown again . Since the ship was sailing, did not burn and looked intact, they thought it was the second US carrier suspected in the region and scored two torpedo hits amidships, which made Yorktown again incapable of maneuvering and a burning floating wreck, but still not fatally hit. Enough Japanese fighter planes returned to the Hiryū to prepare for a third wave of attacks. The Yorktown was, however, bring in the air and after their own machines Hiryu be looking for. They found this in the afternoon.

As bad news for the Japanese, a Japanese scout reported the association of the two aircraft carriers Hornet and Enterprise . When circling, however, the observer made a mistake and reported a formation of four aircraft carriers.

At around 5:00 p.m. SBD dive bombers took off from the Enterprise , with ten bombers arriving from Yorktown . They hit the Hiryū with four bombs despite being protected from the hunt , which destroyed the front flight deck and set the aircraft carrier on fire. The drive of the Hiryū worked until midnight , when the fire stopped the engines. The crew left the ship and Japanese destroyers were ordered to torpedo the burned-out wreckage so that it would not fall into the hands of the Americans. Early on the morning of June 5, a search plane of the small carrier Hōshō found the apparently abandoned ship and found that there were still survivors on board. The destroyer Tanikaze drove to the position of the Hiryu but found no one. He was attacked by more than 50 American aircraft later that day, but was able to escape with successful evasive maneuvers and shoot down an SBD in the process.

During the night, the Japanese battleship formation drove to Midway at top speed to destroy the base. The attack was canceled, however, because the combat power of the aircraft of four assumed aircraft carriers and Midway were considered too dangerous, especially since they no longer had any fighter protection themselves.

At 2:55 a.m. on June 5, Yamamoto finally ordered the battle to be abandoned and the entire fleet to retreat westward.

Aftermath

The Yorktown was torpedoed and badly hit by the Japanese submarine I-168 on June 6th . At this time the Americans were lying alongside the destroyer Hammann to carry out repair work. He too received a hit and sank within minutes. The Yorktown sank the next morning.

Until June 7, American planes repeatedly bombed individual ships in the Japanese fleet. During these attacks, the heavy cruiser Mikuma was sunk. The Trout , an American submarine, discovered two survivors on June 9th.

On June 14th, a scout sighted a small boat hundreds of miles west of Midway. This sighting was repeated on June 19, and the Ballard entered the area. There she found the 35 survivors of the Hiryū who had been seen on board by the Japanese on the morning of June 5th. They found a boat just before the ship sank and have been floating in the sea ever since.

Importance of the battle

The Japanese lost four of their six large aircraft carriers and many of their trained pilots at Midway. Their aircraft crew losses weighed heavily compared to those of the Americans, because they included a lot of training personnel who had been recalled from the flying schools for missions at the front. As a result, the Japanese had greater difficulties with pilot training than the Americans.

This made the Battle of Midway the turning point in the Pacific War. Before Midway, the Japanese had the initiative. Because of their superiority, they determined where and when to fight, while the Allies were too weak for larger operations of their own and could only wait for the next Japanese attack. Due to the heavy loss of porters and pilots, this changed, now both sides were about equally strong. Japanese operations after Midway were all ultimately futile attempts to regain the initiative lost at Midway. Two months after the battle, the Allies began their first offensive with the landing on Guadalcanal . After that, until the Japanese surrender in 1945 , the Japanese Navy only tried to counter the advances of the increasingly stronger allies, which, however, came ever closer to the Japanese heartland.

Even so, the Battle of Midway was not the decisive battle it is often viewed as. Although it greatly weakened the Japanese fleet and restored the balance of power in the Pacific, this was inevitable from the beginning of the war. “If I get orders to wage war regardless of the consequences, I will fight wildly for six months or a year. But if the war lasts a second or third year, I see it extremely black! ” Admiral Yamamoto had assessed the situation of Japan before the war, knowing the enormous industrial superiority of the USA.

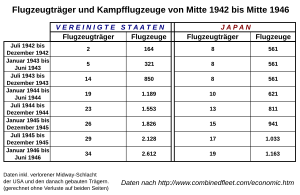

At that time, the world's largest military shipbuilding program of all time had already started in the USA. The production of warships was in full swing. Even a complete defeat of the USA with the loss of all carriers used by Midway without Japanese losses would only have been a short-term, temporary success for Japan. As early as mid-1943, the number of new aircraft carriers launched and operational, including their warplanes, exceeded the production of the Japanese carriers. By the end of the war, the USA's preponderance was overwhelming, even if the Japanese had not lost another porter by then. The American victory at Midway accelerated this and allowed the USA to intervene in the European theater of war with greater force earlier than expected in accordance with the “ Germany first ” strategy.

Ships involved

The following ships were involved in the Battle of Midway. Most of them, however, without fighting.

| Type | Surname | Notable crew members | status | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft carrier | Akagi |

Nagumo Chūichi

Captain: Aoki Taijiro

|

sunk | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Aircraft carrier | Kaga | Captain: Okada Jisaku †

|

sunk | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Aircraft carrier | Hiryu | Captain: Yamaguchi Tamon †

|

sunk | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Aircraft carrier | Sōryū | Captain: Yanagimoto Ryusaku †

|

sunk | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Light aircraft carrier | Zuihō | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Light aircraft carrier | Hosho | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Seaplane carrier | Chitose | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Seaplane carrier | Chiyoda | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Seaplane carrier | Nisshin | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Seaplane tender | Kamikawa Maru | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Fuso | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Haruna | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Here | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Hyūga | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Ise | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Kirishima | Captain: Iwabuchi Sanji | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Congo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Mutsu | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Nagato | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Yamashiro | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battleship | Yamato | Isoroku Yamamoto (Commander in Chief) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Atago | Captain: Ijūin Matsuji | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Chikuma | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Chōkai | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Haguro | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Kumano | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Mikuma | sunk | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Mogami | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Myōkō | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Suzuya | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Clays | Abe Hiroaki | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Light cruiser | Jintsu | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Light cruiser | Kitakami | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Light cruiser | Nagara | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Light cruiser | Ōi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Light cruiser | Sendai | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Light cruiser | Yura | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Akigumo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Amagiri | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Amatsukaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Arare | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Arashi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Arashio | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Asagiri | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Asashio | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Asagumo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Ayanami | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Fubuki | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Hagikaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Kuroshio | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Kazagumo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Kasumi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Kagerō | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Isonami | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Isokaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Hayashio | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Hatsuyuki | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Hatsukaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Harusame | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Hamakaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Maikaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Makigumo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Minegumo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Mikazuki | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Murakumo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Murasame | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Natsugumo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Nowaki | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Oyashio | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Samidars | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Shikinami | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Yūkaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Yūgumo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Yūgiri | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Yūdachi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Uranami | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Urakaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Tokitsukaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Tanikaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Shirayuki | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Shirakumo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Shiranui | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Yukikaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-17 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-26 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-121 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-122 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-123 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-156 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-157 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-158 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-159 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-162 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-164 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-165 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-166 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-168 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-169 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-171 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-174 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | I-175 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Akebono | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Genyo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Kenyo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Kukoyu | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Kyokuto | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Naruto | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Nichiei | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Nippon | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | San Clemente | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Sata | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Shinkoku | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Toa | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Toei | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Tōhō | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | Tsurumi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| PT | Shimakaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| PT | Nadakaze | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| PT | Susuki | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| PT | Tsuta | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Icebreaker | Soya | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Repair ship | Akashi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mine layers | Magane Maru | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Troop transport | 18th | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anti-mine vehicle | 7th | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Auxiliary cruiser | 2 |

| Type | Surname | Notable crew members | status | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft carrier | USS Enterprise |

Raymond A. Spruance (Commander in Chief)

Captain: George D. Murray

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Aircraft carrier | USS Yorktown |

Frank Jack Fletcher

Captain: Elliott Buckmaster

|

sunk | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Aircraft carrier | USS Hornet | Captain: Marc Andrew Mitscher

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Astoria | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Minneapolis | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | New Orleans | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | Northampton | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | USS Pensacola | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | USS Portland | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy cruiser | USS Vincennes | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Light cruiser | USS Atlanta | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Aylwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Anderson | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Balch | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Benham | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Blue | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Clark | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Conyngham | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Dewey | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Ellet | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Gwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Hammann | sunk | |||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Hughes | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Maury | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Monaghan | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Monssen | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Morris | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Phelps | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Russel | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Ralph Talbot | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| destroyer | Been | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Cachalot | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Cuttlefish | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Dolphin | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Finback | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Flying fish | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Gato | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Grayling | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | grenadier | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Grouper | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Growler | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Gudgeon | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Narwhal | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | nautilus | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | pike | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Plunger | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Tambor | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Tarpon | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Trigger | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Submarine | Trout | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | USS Cimarron | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | USS Guadalupeon | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | USS plate | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AO | USS Kaloli | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| PT | 16 PT speedboats | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| tractor | USS Vireo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AVD | USS Thornton | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AVD | USS Ballard |

literature

- Robert D. Ballard: Return to Midway. The search for the sunken ships of the greatest battle in the Pacific. Ullstein, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-550-08302-5 .

- Robert J. Cressmann (Ed.): A Glorious Page in Our History. The Battle of Midway, June 4-6, 1942. Pictoral Histories Publishing, Missoula / Montana 1990, ISBN 0-929521-40-4 .

-

Fuchida Mitsuo , Masatake Okumiya: Midway: The Battle That Doomed Japan, the Japanese Navy's Story. Bluejacket Books, 2001, ISBN 1-55750-428-8 .

- this: Midway - The most decisive naval battle in world history. Stalling, Oldenburg 1956.

- Mark Healy: Midway, 1942 (Campaign). Osprey Publishing, 1998, ISBN 1-85532-335-4 .

- Daniel V. Hernandez (with CDR Richard H. Best, USN Ret.): SBD-3 Dauntless and the Battle of Midway. Aeronaval Publ., Valencia 2004. ISBN 84-932963-0-9 .

-

Walter Lord : Midway. The Incredible Battle. Wordsworth, 2000, ISBN 1-84022-236-0 .

- ders .: Incredible Victory. 1967; German v. Helmut Degner: The battle for Midway. Scherz, 1977, ISBN 3-502-18417-8 ; Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1979, ISBN 3-404-01009-4 ; Naumann & Göbel, Cologne undated (approx. 1985) (all revised by the same, sends them to the bottom of the sea. )

- John B. Lundstrom: Black Shoe Carrier Admiral. Frank Jack Fletcher at Coral Seas, Midway & Guadalcanal. Naval Institute, Annapolis (Maryland) 2006, ISBN 1-59114-475-2 .

- Samuel Elliot Morison: Coral Sea, Midway and Submarine Actions: May 1942-August 1942. (History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 4). Reprint, Castle Books, 2001, ISBN 0-7858-1305-5 .

- Elmar B. Potter, Chester W. Nimitz, Jürgen Rohwer: Seemacht. A history of naval warfare from antiquity to the present. Pawlak, Herrsching 1982, ISBN 3-88199-082-8 .

- Gordon W. Prange: Miracle at Midway. Penguin, Harmondsworth 1982, ISBN 0-14-006814-7 .

- Jonathan Parshall, Anthony Tully: Shattered Sword. The untold story of the Battle of Midway. Potomac, Dulles (Virginia) 2005, ISBN 1-57488-923-0 .

- Earle Rice: The Battle of Midway (Battles of World War II). Lucent, 1995, ISBN 1-56006-415-3 .

- Oliver Warner: Great naval battles. Ariel, Frankfurt 1963.

- Harry Thürk : Midway. Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-327-01211-3 .

Media reception

documentation

- The Battle of Midway : US Navy propaganda filmby director John Ford filmed during the battle, USA 1942, released on DVD in 2003.

Feature films

- Storm over the Pacific ,1949American war film by Delmer Daves about the development of US aircraft carriers.

- Battle of Midway , feature film from 1976, director: Jack Smight , actors: Charlton Heston , Henry Fonda , James Coburn , Glenn Ford , Hal Holbrook , Toshirō Mifune , Robert Mitchum , Robert Wagner u. v. a., Music: John Williams , released on DVD in 2003.

- War and Remembrance , 1988 TV miniseries; Director: Dan Curtis , actors: Robert Mitchum , Jane Seymour , Hart Bochner , Sharon Stone , Robert Morley . 12 parts, 1620 min. Part 3 is about the Battle of Midway. Based on the novel of the same name by Herman Wouk .

- Midway - For Freedom , American feature film from 2019, director: Roland Emmerich , actors: Luke Evans , Woody Harrelson , Patrick Wilson , Mandy Moore u. a. Music: Harald Kloser , Thomas Wanker .

Web links

- Comprehensive battle description on ibiblio.org (English)

- The ONI Review - The report of the Japanese Admiral Nagumo about the battle (English)

- The CINCPAC report by Admiral Chester A. Nimitz Admiral Ernest J. King (English)

- Brief description with very extensive map material on ibiblio.org (English)

- Battle of Midway, June 4-7, 1942 Overview and Special Image Selection. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on January 4, 2015 ; accessed on August 29, 2017 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Walter Lord : Midway: The Incredible Battle. Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 2000, ISBN 1-84022-236-0 .

- ↑ Report by Captain PR White. (PDF; 1.3 MB) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on October 4, 2012 ; accessed on August 28, 2017 . , June 6, 1942.

- ↑ The Japanese rank Shōi corresponds to the German rank of lieutenant in the sea . The prefix Kaigun indicates that it is a marine rank .

- ↑ Joachim Wätzig: The Japanese Fleet - From 1868 to today. Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-89488-104-6 , p. 183.

- ↑ http://www.wlb-stuttgart.de/seekrieg/42-06.htm

- ^ Battle of Midway , public domain download from archive.org .