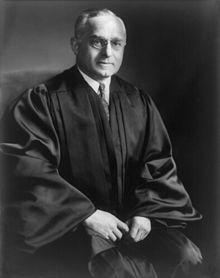

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (born November 15, 1882 in Vienna , Austria-Hungary , † February 22, 1965 in Washington, DC ) was an American lawyer and from 1939 to 1962 a judge at the Supreme Court of the United States .

Early life

Felix Frankfurter's parents, Leopold and Emma Frankfurter (née Winter), emigrated with their family to the United States in 1894 . Leopold Frankfurter's uncle was the director of the Vienna University Library Salomon Frankfurter (1856–1941). The Jewish Orthodox family came from Pressburg . Frankfurter grew up in the Jewish quarter of New York's Lower East Side . After graduating from City College of New York , he left New York in 1902 and studied at Harvard Law School , where he worked on the Harvard Law Review and graduated with one of the best degrees since Louis Brandeis .

Legal career

1906 Frankfurt assistant to the New York lawyer Henry L. Stimson . President Taft named Stimson Secretary of War in 1911 , after which Stimson hired Frankfurter as a lawyer in the Bureau of Insular Affairs .

In 1919 he married Marion A. Denman and took part in the Paris Peace Conference as a representative of the Zionists . He worked with President Woodrow Wilson to include the Balfour Declaration directly in the peace treaty. Frankfurter helped found the American Civil Liberties Union in 1920 and in attempts to save the lives of the Italian-born Sacco and Vanzetti in the late 1920s .

Criminal Justice in Cleveland

In 1922 Frankfurter and Roscoe Pound undertook an intensive study of crime reporting during January 1919 in Cleveland, Ohio . They found that the press coverage of criminal cases had increased nearly sevenfold from the first half of the month to the second half of the month, even though the number of actually reported criminal cases had only grown from 345 to 363. They concluded that while the sharp rise in Cleveland crime depicted was largely fabricated by the press, that fiction had a real impact on the work of law enforcement. Believing that the city was facing an acute "epidemic" of crime, the population called for a tougher crackdown and increased police force. Politicians in the city administration complied with the demands for reasons of election tactics. The result was often tougher penalties for the same acts, which were much more easily punished before the panic.

His extensive research into the distribution of power within the US government led him to conclude that "the real rulers of Washington are invisible and exercise their power behind the scenes."

In 1932 Frankfurter was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . Since 1939 he was an elected member of the American Philosophical Society .

Supreme Court

On January 5, 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt nominated Frankfurter as Supreme Court Justice. He served in this office from January 30, 1939 through August 28, 1962.

A few months after taking over his office, Frankfurter wrote - at least linguistically - legal history with the famous metaphor fruit of the poisonous tree. With this he justified the decision of the court per curiam , with which a relatively extended prohibition on the use of evidence was established in the criminal law of the United States.

In addition to his liberal political attitudes, Frankfurter was one of the most ardent advocates of the point of view known as judicial self-restraint , which emphasizes the separation of powers and opposes a constitutional interpretation that restricts the scope for shaping politics through legal requirements. The primary goal of this doctrine is to focus the judge's role on the function of an independent legal practitioner and basically forbid him to make his own legislation, since it is the sole responsibility of Parliament. This philosophy also reflected the influence of his mentor Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. , who vigorously opposed the concept of the "economic due process " during his own tenure . Frankfurter admired Judge Holmes and often quoted him in his reasons for the decision. For his work at the Supreme Court, this attitude meant that Frankfurter gave the actions of these powers a broad constitutional freedom, as long as they did not "shock the conscience".

In the course of his later term in office, Frankfurter often found himself on the side of the minority. As a clear enemy of racial segregation , he voted with a unanimous majority in the Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which declared the separation of schools by skin color to be unconstitutional.

Felix Frankfurter and Jan Karski

Jan Karski stayed in Washington in July 1943 to meet various influential people, u. a. also Judge Frankfurter to report on the desperate situation of the Jews in Poland. In his speech in the Cologne synagogue and in the subsequent conversation on January 27, 1997, he said:

“Felix Frankfurter, judge at the US Supreme Court, born in a Jewish family in Ostia, asked me to tell him everything I knew about the Jews. He wasn't interested in anything else, and for 20 or 25 minutes I only talked about the Jews - what I had seen in the ghetto, in the camp. He asked me about some technical details - how I would have gotten into the ghetto, how high the wall around the Warsaw ghetto was, etc. - and I remember every word, every gesture by Judge Frankfurter during this conversation. After 20, 25 minutes I couldn't think of anything. So I stopped, and for a few moments there was an awkward silence. Then Judge Frankfurter got up and began to run around, always in front of me. To my left sat the Polish Ambassador Ciechanowski . Frankfurter sat down again and said (I remember every word and gesture, because it was a bit bombastic): 'Mr. Karski, someone like me speaking to someone like you has to be very frank. So I say, I can't believe what you told me. ' Then the ambassador, who was a personal friend of the judge, jumped up: 'Felix, you can't tell him in the face that he is lying. You don't mean that. My authority and that of my government stand behind him. ' Judge Frankfurter: 'Mr. Ambassador, I did not say that this young man was lying. I said I was unable to believe what he was telling me. ' And he stretched his arms in my direction and said: 'No, no!' I remember later asking the ambassador, 'Tell me, was that a comedy? Or did he really not believe me? ' I remember the ambassador telling me, 'Jan, I don't know, I really don't know. But you must realize that you are indeed reporting incredible things. '"

retirement

Frankfurter retired in 1962 after suffering a stroke . His seat on the Supreme Court was taken over by Arthur Joseph Goldberg . In 1963 Frankfurter was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom .

Felix Frankfurter died of heart failure at the age of 82 . His remains were interred in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts .

Fonts

Frankfurter published several books, including

- The Business of the Supreme Court (1927)

- Justice Holmes and the Supreme Court (1938)

- The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti (1954)

- Felix Frankfurter Reminisces (1960).

He was known as an eminent scholar in the field of labor law. From 1914 until his appointment to the Supreme Court, he was a professor at Harvard Law School and served President Roosevelt as an informal advisor to many New Deal initiatives.

literature

- Leonard Baker: Brandeis and Frankfurter: A Dual Biography , New York 1984. ISBN 0-06-015245-1

Web links

- Literature by and about Felix Frankfurter in the catalog of the German National Library

- Felix Frankfurter's grave

- Newspaper article about Felix Frankfurter in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Remarks

- ↑ John R. Vile, Kermit Hall, John R. Vile: Great American judges: an encyclopedia , John R. Vile, 2003, ISBN 978-1-5760-7989-8 , p. 264 (also on google book)

- ↑ Klaus Bruhn Jensen: A Handbook of Media and Communication Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methodologies . Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-415-22588-4 , pp. 45-46 .

- ^ Roscoe Pound, Felix Frankfurter: Criminal Justice in Cleveland . The Cleveland Foundation, Cleveland, OH 1922, pp. 546 .

- ^ Member History: Felix Frankfurter. American Philosophical Society, accessed August 11, 2018 .

- ↑ Nardone v. United States , docket no.240 (1939)

- ^ Wolf Oschlies : Jan Karski (1914–2000). Misunderstood warner of the Holocaust . In: Working Group Future Needs Memory (ed.): Future Needs Memory , October 1, 2004.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Frankfurter, Felix |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American lawyer, United States Supreme Court Justice |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 15, 1882 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 22, 1965 |

| Place of death | Washington, DC |