Sacco and Vanzetti

Ferdinando "Nicola" Sacco (born April 22, 1891 in Torremaggiore , Province of Foggia , Italy ; † August 23, 1927 in Charlestown , Massachusetts ) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (born June 11, 1888 in Villafalletto , Province of Cuneo , Italy; † August 23 1927 in Charlestown, Massachusetts) were two workers who immigrated to the United States from Italy and had joined the anarchist labor movement .

You were charged with involvement in a double robbery murder and found guilty in a controversial trial in 1921. After several rejected appeals by the legal profession , the death sentence followed in 1927 after seven years in prison . On the night of August 22-23, 1927, Sacco and Vanzetti were executed on the electric chair in Charlestown State Prison .

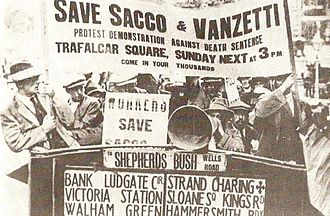

Both the guilty verdict and the final verdict of April 9, 1927 resulted in mass demonstrations around the world. Critics accused the US judiciary of a politically motivated judicial murder based on questionable evidence . Exonerating indications were insufficiently appreciated or even suppressed. Hundreds of thousands of people took part in petitions in an attempt to obtain a postponement or suspension of the execution of the sentence.

In 1977, Democratic Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis issued a statement that the trial of the duo was "steeped in prejudice against foreigners and hostility to unorthodox political views" and was therefore unfair.

backgrounds

Biographical background

Nicola Sacco

Ferdinando "Nicola" Sacco was born on April 22nd, 1891 in Torremaggiore in southern Italy. He was the third of a total of seventeen children. His father sold olive oil and wine from his own production. Baptized Ferdinando, he changed his first name to Nicola after a brother with that name died. Nevertheless, his baptismal name was still used by him and his friends.

It is not certain whether he attended school as a child. In any case, he helped his father cultivate the fields at an early age. Agriculture did not interest him, however. When his older brother Sabino was invited by a friend of his father's to Massachusetts, USA, Nicola was happy to come along. At the age of almost seventeen, he arrived in America on April 12, 1908. He got by as a water carrier for a construction company and worker in a foundry . When Sabino returned home about a year later, Nicola stayed in the United States at her own request. He trained as a skilled worker in the Milford Shoe Company in 1910 and now earned a little more money as an employee than before. In 1912 he married the then seventeen year old Rosa Zambelli, usually called Rosina by Sacco. Their son Dante was born in 1913. Sacco has been described by friends and relatives as a loving father and a family person. At the time of his arrest, his wife was five months pregnant with daughter Ines.

The young Sacco was already inspired in Italy by his brother Sabino for socialist ideas. In the United States, he and his wife were involved in a group of Italian anarchists. In 1916 he was arrested and fined for speaking at an unauthorized meeting of anarchists. Because he feared being drafted for military service, he fled to Mexico with other anarchists for a few months in 1917 . Among them was Vanzetti, whom he had met about a week earlier. After his return, Sacco worked as an unskilled worker for various companies and shoe factories. At the 3-K Shoe Company , the owner Michael F. Kelley, who had previously been a department head at the Milford Shoe Company , remembered Sacco's reliability and hard work. Sacco was hired there in November 1918 and earned up to eighty dollars a week through piecework , which was an above-average salary. In the winter of 1918/19 he also took care of the boiler and the heating of the company building, for which he went to the factory every night. He is therefore often mistakenly described as the company's night watchman.

Bartolomeo Vanzetti

Bartolomeo Vanzetti was born on June 11, 1888 in Villafalletto near Cuneo. His mother already had a son from a previous marriage. After the death of her husband, she married Giovanni Vanzetti. Bartolomeo was the first of four children of the Vanzettis. Bartolomeo attended school for at least three years, the exact duration is not reliably proven. He is described as a curious and inquisitive child. However, his father Giovanni, who ran a coffeehouse in Villafalletto in addition to a farm, determined that the son became a confectioner . Bartolomeo left home at the age of 13 to begin his apprenticeship. During the strenuous training period in various Italian cities, illnesses plagued him again and again. At the age of 19, now in Turin , he was brought home with severe pleurisy . He never returned to work as a confectioner. Instead, he first worked in his family's garden. The year he returned, his mother died of liver cancer , which affected Vanzetti very much. Against the will of his dominant father, Vanzetti left his homeland in 1908, just before his 20th birthday, to emigrate to the USA.

There he kept himself afloat doing odd jobs, moving from town to town before settling in Plymouth , Massachusetts in 1913 . He lost his job with the Plymouth Cordage Company after actively participating in a strike. In autumn 1919 he started his own business as a fish seller. Vanzetti lived in Plymouth with the Italian anarchist Vincenzo Brini as a subtenant. He himself had neither married nor children, but he developed an intimate relationship with the Brini family and their three children. After he fled to Mexico and returned to Plymouth in 1917, the Brini family could no longer accept him due to lack of space, and he lived with the Fortini family until his arrest.

Shaped by the painful experiences as an unemployed person in the first few years in the States, his doubts about religion grew and he turned increasingly to anarchist ideals. In his autobiography he wrote:

“In America I experienced all the sufferings, disappointments and hardships that are inevitably the lot of a person who arrives here at the age of twenty, knows nothing about life and has something of a dreamer in him. Here I saw all the cruelty in life, all the injustice and corruption that humanity struggles with in such a tragic way. [...] I looked for my freedom in everyone's freedom, my happiness in everyone's happiness. "

Joint activities

Sacco and Vanzetti had emigrated from Italy to America in 1908, but met for the first time in May 1917. By this time they had joined the anarchist movement around Luigi Galleani . Galleani himself was arrested and deported in 1919 because of the rigid policy against foreign radicals .

Shortly before Sacco and Vanzetti met, the United States entered the First World War by declaring war on Germany in April 1917 . The escape of the two to Mexico was made with the intention of evading the draft and the threat of military action in the war, which was essentially fought on European battlefields. In fact, foreigners whose naturalization process had not yet been completed could not actually be obliged to serve in the war under the law. They returned three or four months later, but for some time used false names as they faced jail time for escaping from registration.

The letters the two of them wrote to each other during their imprisonment for the robbery of South Braintree - most of the time they were housed in separate cells and prisons - suggest more of a friendship than a warm friendship.

Historical-political background

With the end of the First World War in November 1918, the USA fell into an economic depression . The number of unemployed rose sharply and prices rose steadily. In addition to strikes, an increased crime rate was the result of the disastrous economic situation. In addition, the successful communist revolution in Russia shocked the then ruling US political leadership. For in the United States, too, left forces were now gaining presence: In September 1919, after splitting off from the Socialist Party, the Communist Party and the Communist Labor Party were founded . There were also various groups of anarchists and others from the spectrum of the revolutionary left, each with different ideological orientations. The government propaganda blamed the political left across the board for the poor situation in the country and described them indifferently as criminal “ Bolsheviks ” who would do anything to bring about a communist revolution in the USA. The fomented " Red Scare " ( Red Scare ) was by a number of bombings nourished, have been assigned to the anarchists. On June 2, 1919, eight bombs exploded in various cities in the country. In addition, there were leaflets with threats from “anarchist fighters” against the “capitalist class”.

Fear of “ Bolsheviks ” went hand in hand with fear of immigrants. According to propaganda, the latter made up 90 percent of all radicals in the country. The attorney general Alexander Mitchell Palmer , whose house was damaged in one of the attacks, then carried out brutal raids on institutions and organizations by and for foreigners from November 1919. The general public welcomed these so-called Palmer Raids , which aimed to track down “individuals prone to radicalism” and expel them from the country. With reference to the imminent danger for the country, applicable laws were disregarded or changed to the detriment of the immigrants affected. In addition, witnesses and reporters reported serious attacks on the - mostly innocent - arrested.

The trail of the anarchist leaflets led the investigating agents to a print shop in Brooklyn . Two of the employees were arrested in February 1920. One of them, the typesetter Andrea Salsedo, fell from the 14th floor of a New York police building on the morning of May 3rd. He had been detained and interrogated for two months without a warrant . Torture rumors were circulating in anarchist organizations. The circumstances of the fatal fall could never be fully clarified. This incident caused great concern and fear of further raids among anarchist groups.

The robberies

On the morning of December 24, 1919 came in Bridgewater to a robbery on an armored car. The robbery failed and the armed gangsters fled without prey.

About four months later, on April 15, 1920, two men armed with handguns shot dead in South Braintree , Massachusetts, payroll clerk Frederick Parmenter and security officer Alessandro Berardelli, two employees of the Slater & Morrill Shoe Company . The perpetrators looted $ 15,776.51 (value in 2021 approx. $ 201,000) in wages that the victims carried with them. They escaped in a dark blue Buick with two or three other men in it. That this double robbery was linked to the Bridgewater robbery has never been proven beyond doubt. However, the investigating authorities assumed this. After his arrest as a suspect in the South Braintree case, Vanzetti had to answer in court for the attempted robbery in Bridgewater.

Before the trial

Investigation and arrest

The police's initial suspicion that the so-called Morelli gang might be behind the robbery in South Braintree was quickly dropped by the Bridgewater Police Chief Michael E. Stewart. He suspected anarchists behind the robbery. In doing so, he apparently relied on the following evidence : A radical named Ferruccio Coacci, who was to be deported for distributing anarchist writings, did not report on April 15, as agreed with the authorities. From this, Stewart concluded that Coacci could have been one of the perpetrators in South Braintree. Stewart also believed the robberies in South Braintree were linked to the attempted robbery of the money truck in Bridgewater four months earlier. According to an unconfirmed testimony , the latter was said to have been carried out by a group of anarchists.

Stewart had the house searched in which the now deported Coacci had lived. In the shed he thought he saw tire marks from a Buick and thus the getaway car. Mike Boda ( also: Mario Buda), who also belonged to an anarchist organization, lived in the house. He stated that his Overland brand car was normally stored in the shed, but that it was currently in a workshop for repairs. After the police visit, Boda went into hiding. Stewart then directed the garage owner to call him as soon as Boda was due to pick up his car.

On the evening of May 5, 1920, Boda came to the workshop with three other men from his anarchist organization. Among them were Sacco and Vanzetti. The owner's wife informed the police by phone. It is not certain whether Boda and the others noticed this. It is certain that the men left prematurely and without the car: Boda and one of the companions on a motorcycle that they had also come with, Sacco and Vanzetti on foot. After about a mile, the two of them got on the tram towards Brockton . Meanwhile, the Brockton Police were briefed by Stewart. Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested as "suspects" while they were still in the tram. When she was arrested, both had guns with them: Sacco had a Colt 32 , Vanzetti had a Harrington & Richardson 38 revolver and several shotgun cartridges .

Sacco and Vanzetti were interrogated separately at Brockton Police Station, first by Stewart, and a day later by the District Attorney of Norfolk County , Frederick G. Katzmann . They were not told the reason for their arrest. They were not or only indirectly questioned about the robbery murders themselves; the interrogations focused on their political attitudes. Both lied about acquiring the guns and denied being anarchists or adhering to any other left-wing ideology. They also stated that they knew neither Boda nor Coacci.

The others who wanted to pick up the car were also suspected. But there was no agreement with the testimony and the remarkably short stature Mike Boda. The other companion had a clear alibi . Against Sacco and Vanzetti, there was no evidence or evidence that would necessarily have linked them to one of the robberies. A comparison of the fingerprints on the seized getaway car did not match. An investigation could not confirm the suspicion that the stolen money would have been received by anarchist organizations. However, the negative result and the investigation itself were not admitted by the Justice Department until August 22, 1927, the day before the execution. Both Katzmann and Stewart maintained that both robberies were carried out by a certain group of anarchists and that Sacco and Vanzetti were involved.

Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee

In the course of the arrest and charges against Sacco and Vanzetti, who appeared ideologically motivated, the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee was formed under the leadership of the anarchist Aldino Felicani, who was experienced with propaganda . This committee publicized the case, raised money and appointed defense lawyers. The extent to which the activities of the committee benefited or harmed Sacco and Vanzetti remains controversial even when considering the case as a whole.

Bridgewater: Indictment and verdict against Vanzetti

According to statements by the factory manager and his work colleagues, Sacco had a valid alibi for December 24, 1919, the day of the Bridgewater attack. Thus only Vanzetti was charged on June 11, 1920 with attempted robbery and murder in Bridgewater. The trial began on June 22, 1920 in Plymouth under the presidency of Judge Webster Thayer .

The indictment, led by Katzmann, was essentially based on three witnesses, who in the course of the preliminary investigation and the trial, in some cases significantly tightened their statements to the disadvantage of Vanzetti. Vanzetti's alibi was confirmed by fourteen Italians who said that Vanzetti had sold them or others eels for Christmas Eve on the morning of December 24th. Concerned by his lawyers that his political views could be used by the jury against him, Vanzetti decided not to testify.

Judge Thayer instructed the jury that the Italian nationality of the defense witnesses should not be interpreted to their disadvantage: “No unfavorable conclusions should be drawn from the fact that the witnesses (of the accused) are Italians. “On July 1, 1920, the jury found Vanzetti guilty of robbery and murder. Judge Webster Thayer sentenced him to twelve to fifteen years in prison on August 16, which he served until he was executed in Charlestown Prison .

The trial of Sacco and Vanzetti

After the surprising guilty verdict in the Bridgewater trial, Felicani was looking for a new defense attorney. The well-known radical Carlo Tresca recommended the eccentric lawyer Fred H. Moore , who had already been involved in successful defense cases of radicals and anarchists. Moore began work in August 1920. In doing so, he concentrated on the political dimension of the case and mobilized large circles, especially left-wing and anarchist groups. Vanzetti followed Moore's successful propaganda efforts with consent. Sacco, on the other hand, was skeptical and rejected Moore's often provocative methods. Regardless, the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee stuck to Moore.

The trial began on May 31, 1921 in Dedham , Massachusetts. As in the Vanzetti trial in Plymouth, prosecutor Frederick G. Katzmann brought the indictment. Judge Webster Thayer was again in the chair - at his own request.

Witnesses to the robbery

Of a total of 33 witnesses who were supposed to testify about Sacco's involvement in the robbery, only seven believed in court that they actually saw him near the scene of the crime or at least a few hours before. Because these witnesses changed their statements up to the trial in some cases and also made contradictions noticeable, their evidential value was heavily doubted during the ongoing trial.

Five witnesses testified against Vanzetti. Their statements also differed in some cases strikingly from those made previously. Three of them did not witness the robbery itself. Vanzetti was exonerated by thirty-one witnesses who ruled out having seen him during the crime.

The judge also later stated: "In my opinion, these judgments were not based on the statements of the eyewitnesses, because the defense called more witnesses than the prosecution, witnesses who testified that none of the accused had been in the gangster car."

Evidence

In the course of the trial, the public prosecutor alleged that the revolver Vanzetti was carrying when he was arrested came from the property of the murdered guard Alessandro Berardelli. The defense, in turn, believed that they could prove the opposite by testimony from previous owners of the revolver. It was also not certain that Berardelli was even carrying his weapon on the day of the robbery, as he had previously returned it to a repair shop. A workshop worker could neither confirm nor deny that Vanzetti's revolver was identical to the Berardelli's.

Prosecutors also produced a cap that was allegedly found next to Berardelli's body. In fact, a factory worker only discovered the said cap on the street one day after the robbery murder. According to a witness, the cap was outwardly similar to a cap that Sacco used to wear. When Sacco was asked to put it on in court, it turned out to be too tight. Judge Thayer recognized highly incriminating evidence against the defendants in both the cap and the revolver.

The strongest and most controversial piece of evidence was the bullet which, according to the indictment, was fired from Sacco's Colt and which caused the death of Alessandro Berardelli ("Bullet III"). However, this piece of evidence was not brought in by the public prosecutor, but by the defense: Moore requested ballistic tests on the bullet on June 5, 1921 . The tests on June 18 led to three reports from various experts. The defense report ruled out that the bullet was fired from Sacco's Colt. Another expert saw this as possible (“I am inclined to believe […]”). The statement of the third expert William H. Proctor was fatal for Sacco:

- Harold P. Williams (assistant district attorney): "Have you come to any conclusion as to whether the Bullet III presented here as evidence was fired from the automatic Colt?"

- Proctor: "I am."

- Williams: "And what is your opinion?"

- Proctor: "My opinion is that it is consistent with being fired by that pistol."

Thayer assessed this linguistically ambiguous statement to the jury as evidence against Sacco. In his affidavit after the end of the trial, however, Proctor emphasized that he only wanted to explain that the bullet had come from an automatic Colt, but not necessarily from Saccos.

The dispute over the evidential value of the ballistic tests on Sacco's weapon continued for years after the verdict and continues to this day. Further investigations in the course of the readmission requests produced contradicting results. In addition, there were indications that both the barrel of Saccos Colt and the bullet itself had been replaced.

Alibis

Vanzetti stated that he went about his normal activities on the day of the attack, but also bought fabric for a new suit. The rather weak alibi was confirmed by witnesses. In the cross-examination , Katzmann tried to make the witnesses appear implausible.

Sacco said he wanted to get a document for the planned trip home to Italy. He would have decided to take this step on hearing the news of his mother's death. He therefore took off April 15 to visit the Italian consulate in Boston. Three witnesses confirmed meeting Sacco in Boston, including the consulate clerk. Surprisingly, Sacco also recognized a man among the spectators in the courtroom whom he had seen on the train returning from Boston. The man was able to confirm Sacco's information in cross-examination.

Regarding Boda's car, which they wanted to pick up on the day of the arrest, Sacco and Vanzetti stated that they wanted to use it to collect radical writings: the anarchists expected further raids in the wake of the incidents surrounding the anarchist Andrea Salsedo.

Importance of patriotism in the process

Although not relevant to the alleged robbery murders, prosecutor Katzmann emphasized during the cross-examination of Sacco and Vanzetti their escape from military service. He accused them of not loving America ("Is that your idea of proving your love for America?").

Katzmann concluded his plea to the jury with the request: “Stand together, men of Norfolk!” At the final briefing of the jury on July 14, 1921, Judge Thayer swore the value of loyalty: “There is no better word in the English language than ,Loyalty'. Because he who shows his loyalty to God, to his country, to his state and to his fellow men, represents the highest and noblest type of true American bourgeoisie, which has no equal in the whole world. "

After about five hours, Sacco and Vanzetti were found guilty on all counts by the jury. Almost six years later, on April 9, 1927, Judge Thayer pronounced the sentence on the death penalty for the use of electricity.

End of trial until execution

Vocations

The long time that the guilty verdict passed the jury to verdict, is explained by the many attempts by the defense, hear the case again. By 1927, the defense had submitted eight requests for revision . The motions reflect the ongoing criticism of the conduct of the litigation and the resulting verdict.

The first application for a retrial was made on July 18, 1921. The defense took the view that the jury's decision was driven by prejudice and contradicted the evidence. The application was dealt with on November 5th and rejected by Judge Thayer on December 24th. Five additional motions followed within the next two years, which were negotiated in early October and early November 1923. About a year later, Judge Thayer made the decision to reject all five applications.

The most explosive aspect of the first supplementary motion ("Ripley-Daly motion", filed on November 8, 1921) was the affidavit of a friend of the jury chairman Walter H. Ripley: After he had told Ripley that Sacco and Vanzetti were probably innocent Ripley replied: "The hell with them, you should definitely hang them!" Judge Thayer justified the rejection of the application with his respect for the jury chairman, who had since passed away: He was "not prepared to tarnish the memory of Mr. Ripley" .

In the second additional motion ("Gould-Pelser motion", submitted on May 4, 1922), the defense complained that an exonerating witness of the assault was not summoned in court and that they were not informed about this witness. But according to Judge Thayer, the further testimony would be irrelevant to the verdict. Instead, he cited, among other things, the "sense of guilt" of the accused as the decisive factor.

The application also contained the written revocation of an incriminating testimony. However, the witness, Pelser, later stated to public prosecutor Katzmann that this revocation came about under the influence of alcohol and under pressure from Moore. In the run-up to the following two additional motions ("Goodridge motion", filed on July 22, 1922; "Andrews motion", September 11, 1922) Moore is said to have threatened incriminating witnesses to recant their statements. Judge Thayer sharply reprimanded Moore's actions and rejected the applications. There was also increasing resistance to Moore's methods in the Defense Committee.

For the fifth supplementary application ("Hamilton-Proctor application", introduced on April 30, 1923, supplemented on November 5, 1923) two experts (Albert H. Hamilton and Augustus H. Hill) examined the bullet III or the cartridge case again and closed from that these were fired from Sacco's Colt. Two prosecution experts disagreed with this finding. Thayer decided to believe the prosecutor's ballisticians. The application was supplemented with an affidavit from the expert Proctor. This now clearly distanced himself from his misleading statement regarding Sacco’s Colt: The prosecutor would have known that he, Proctor, had no ballistic proof against Sacco. Proctor's actual statement was twisted by the clever questioning. Thayer was appalled by the affidavit of the now deceased Proctor, since "honor and integrity" of the public prosecutor's office would be attacked.

Moore's dismissal

Moore's style, which had to provoke Judge Thayer and the conservative jury, was criticized before the trial. But once commissioned, he refused to submit the case. The tension between Moore on the one hand and Felicani and Sacco and Vanzetti on the other began to escalate, not least because of the apparently unfair methods that Moore used in the follow-up research. Moore founded the Sacco-Vanzetti New Trial League , from which the money raised should now be used to fight for a new trial - with him as the lead defender. Since both Sacco and now Vanzetti vigorously turned against Moore, the New Trial League failed. Moore was released and, disappointed, withdrew from the case in November 1924. His contribution is usually rated ambivalently: The successful endeavor to make the case public as a scandal worldwide is considered to be his merit. At the same time, the politicization carried out is criticized as the reason for its failure in court. That he later turned against Sacco and Vanzetti ("Sacco was likely and Vanzetti possibly guilty.") Is partly interpreted as a result of his bitterness.

Moore was replaced by the renowned, conservative lawyer William Thompson . He was already involved in drafting the fifth amendment and was convinced of the innocence of both defendants. Felicani commented later deeply impressed by Thompson's contribution to the case, the relationship described but as a rather distant: "... he [was] the aristocrat and we, the proletarians ." Thompson rejected the Defense Committee of, all agitation adjust to the clashes with to be able to lead the court more objectively. Though Vanzetti, Felicani, and others on the committee built on public pressure out of deep distrust of the prosecution and court, the Defense Committee eventually followed Thompson's direction. The case has long since attracted worldwide attention. Thompson's talks at court received a great deal of attention in the newspapers.

In January 1926, Thompson defended his appeal against Thayer's ruling and denial of retrial before the Massachusetts Supreme Court . About five months later, the latter confirmed the convictions against Sacco and Vanzetti and Thayer's decision, which was basically covered by the judge's discretion. A judge does not even have to justify why he does not believe, for example, affidavits. The defense’s claim that prejudice was deliberately fueled during the trial was also rejected by the Supreme Court.

Madeiros application

In November 1925, one of the most sensational twists and turns occurred in the Sacco and Vanzetti case. Celestino F. Madeiros, who was placed in the same prison as Sacco for the killing of a bank clerk, sent Sacco a note on November 18, 1925:

“I admit that I was involved in the crime at the South Braintree shoe factory and that Sacco and Vanzetti were not there.

Celestino F. Madeiros "

Madeiros described the attack to lawyer Thompson and later also a representative of the public prosecutor's office, in which he said he was involved as a guard in the getaway car. Since the testimony of a convicted criminal has little credibility in court, the defense commissioned Herbert Ehrmann with investigations based on Madeiros' information. Ehrmann came across new testimony and evidence that seemed to confirm Madeiros' version. Subsequently, he suspected the well-known Morelli gang to be behind the robbery in South Braintree. Among other things, he found weapons in the possession of gang members that seemed to match those weapons that were used by ballistics experts in the robbery according to statements made by the process. According to Ehrmann's observation, most of the personal descriptions on record matched the Morelli brothers or their accomplices. At the end of his research, Ehrmann said he could name or reconstruct the perpetrator, the motive, the weapons, the sequence and the planning of the attack in South Braintree. The prosecution, represented by Dudley Ranney, declined due to existing gaps and inaccuracies of the confession but starting to report to the members of the Morelli gang in this matter advertisement or conduct its own investigations, "We believe we have found the truth, and ... since we have found the truth, nothing else can play a role. "

On May 26, 1926, the defense filed the meanwhile sixth additional motion ("Madeiros motion") for a reopening of the proceedings, which was based, among other things, on Madeiros' confession. Judge Webster Thayer dismissed the motion on October 23, 1926. In his reasoning, he highlighted the passages in the confession that contradicted the course of events reconstructed by the court. He ignored Ehrmann's research results or considered them null and void.

Another part of the motion was the allegation that the prosecution worked with the Justice Department to suppress exculpatory evidence. Thompson relied on two affidavits from former officials, both of whom reported the following:

“The Boston Department of Justice urgently needed sufficient evidence against Sacco and Vanzetti to be able to deport them, but never succeeded in obtaining the […] required type and amount of evidence. According to local ministry officials, convicting Sacco and Vanzetti was one way of getting rid of these two men. "

The Ministry's correspondence with Katzmann should therefore be documented in detail in the files. Thompson wanted to inspect the files, but the prosecution denied him. In the application before the court, Thompson explicitly pointed out this behavior by the public prosecutor and asked the court to order the handover of the files: “There is something more important than punishing Sacco and Vanzetti for this murder, if they had committed it, which, in our opinion, is not the case, and that is that the conviction of guilty people should always be carried out in accordance with the rules of law and justice and a fair procedure, openly and fairly and without secrecy or ulterior motives ... ”Thayer attested in this regard Thompson "hysteria" as the allegations were unfounded. The court could not require the submission of evidence, because "you can not produce anything that does not exist".

Against the rejection of the application and its reasoning, Thompson again appealed to the Supreme Court in Massachusetts. This ruled on April 5, 1927 again in favor of Thayer's discretion. He also referred to a judgment from a civil law suit: "A retrial is not compulsory, even if new evidence was discovered that would lead the jury to a different verdict."

Waiting in jail

Most of the time Sacco and Vanzetti spent in separate prisons, marked by doubts and fears, for decisions to be made on the applications and, ultimately, for the execution : Vanzetti was serving his sentence after the Bridgewater Trial in Charlestown , while Sacco was housed in Dedham Prison. As different as the two men were, just as differently they dealt with the convictions and the impending execution.

Sacco evidently made the situation far more troublesome than Vanzetti, who was described by himself and others as a thinker and dreamer. Separated from his wife and children, Sacco suffered from delusions a few months after the conviction . In February 1923 he went on a hunger strike lasting several weeks . Vanzetti writes in a letter to his sister Luigia, with whom he maintained lively correspondence during his imprisonment: “He is determined to be released or to die. He was without food for twenty-nine days… ”However, he did not want to take part in the hunger strike himself. After an examination, Sacco was admitted to the Boston Psychiatric Hospital to be force-fed. He then began to eat again on his own.

After a brief period of recovery, he had a seizure on March 22nd, when four men had to stop him from beating his head against the armrests of a heavy chair. As a result, he repeatedly expressed intentions to commit suicide . Quiet phases alternated with sudden attacks. The hospital director stated on April 10th that Sacco needed inpatient care and treatment. Less than two weeks later, on Sacco’s 32nd birthday, he was admitted to the hospital for mentally ill lawbreakers in Bridgewater. Thanks to better social contacts - he was no longer isolated in a room - and the opportunity to work on the prison farm, his condition improved significantly. On September 29, 1923, he was transferred back to Dedham Prison.

Vanzetti seemed to find it easier to come to terms with condemnation and imprisonment: "It is said that people only say good about you when you are dead, but they also say good about you when you are in prison." He read a lot, worked on translations and had intensive correspondence, especially with his sister Luigia in Italy. “My body and soul remain strong… My literary works, as poor as they may be, meet with sympathy and approval. In the thirteen years that I have been in this country, I never realized that I had any talent at all, until the present misfortune set in. "

The worker and idealist Vanzetti was not unsatisfied that the condemnation - no matter how much he suffered from it - acquired a meaning that would otherwise never have been given to a person of his class: “I have met many doctors, lawyers and millionaires to whom I would never have gotten near it. And how they love me! They are amazed at what I write, they visit me and bring presents, and they keep writing to me. If I were released, they would open the doors of their homes and let me in and help me in any way they can. "

After Thayer repeatedly refused to reopen the case, the psychiatrists diagnosed Vanzetti with hallucinations and delusions. From January to May 1925 he was placed in the Hospital for the Insane Lawbreaker. However, vague hints in his letters to Luigia suggest that Vanzetti was only faking his mental illness. However, it remains unclear what he wanted to achieve with it: When viewed objectively, it did not stop the impending execution.

Pronouncement of judgment

The verdict on April 9, 1927, took place in Dedham Court with great public interest.

According to the protocol , both were allowed to speak again before the death penalty was ordered. Sacco, who spoke English even worse than Vanzetti, turned to Judge Thayer with only a short speech. He never experienced anything as cruel as this judgment. But he left the talking to his comrade Vanzetti, who would be more proficient in English than he was. Sacco concluded with the affirmation: "[Judge Thayer] knows that I was never guilty, never - not yesterday, nor today, ever."

In his forty-five minute speech, Vanzetti protested his innocence and highlighted the struggle for justice of which he was guilty:

“Not only have I not committed any real crime in my entire life - some sins, but no crimes - [...] but also the crime that official morality and law approve and sanctify: exploitation and oppression of man through man [...] If there is a reason why you can destroy me in a few minutes, then that is the reason and no other reason. "

He sharply denounced what he considered to be the hostile attitude of the courts:

“Not even a dog that kills chickens [would] have been found guilty by an American jury on such evidence as the prosecution has brought against us. I say that not even a mangy dog would have had its appeal twice denied by the Supreme Court [...] "

He recalled Madeiros, who had been granted a new trial on the simple grounds that the judge had not warned the jury that a defendant was innocent until proven guilty. "We have proven that there can be no judge on earth who is more prejudiced and cruel than you were against us."

Vanzetti concluded with the conviction that he had to atone for being a radical and Italian: “… but I am convinced that I am right, and if you could execute me twice and if I could be born two more times then then I would do what I did again. "

Judge Thayer then ordered that Sacco and Vanzetti should suffer "the death penalty by applying electric current to their bodies". The enforcement of the final judgment was scheduled for the week beginning July 10, 1927.

Protests

Mobilizing a global public

In the USA at the time of the process and the appeals - with a few exceptions - only immigrants as well as anarchist and some left-wing groups could be mobilized for protests, whereby the communists, for example, showed no interest in participating. When it became known that neither Madeiros' present confession nor the suspicion of collusion with the Justice Department led to a legal reassessment of the case, conservative intellectuals across the country began to notice the case: In a sensational article in The Atlantic magazine Monthly (March 1927) the lawyer Felix Frankfurter sharply criticized Judge Thayer's decisions. The question of whether Sacco and Vanzetti should die has been the subject of controversial debate in American newspapers and the public .

After the death sentence had been announced, the Defense Committee's campaign , which was now specially tailored to Americans, met with a great response from all walks of life and faith groups: Catholics , Quakers , Presbyterians , atheists , scientists, writers and many others began to stand up for the convicted. This widespread mobilization is mainly due to the journalist Gardner Jackson, who committed himself to the Defense Committee with great personal commitment. The Communist Party, too, began to exploit the case for itself: of the nearly half a million raised, only $ 6,000 are said to have been handed over to the Defense Committee.

Outside the United States, there have been public protests before . The largest demonstrations took place in France and Italy , where tens of thousands of people took part. The peaceful rallies were overshadowed by acts of violence: a bomb exploded in front of the American embassy in Paris . Another bomb was discovered and disposed of in Lisbon before the explosion.

The labor movement protested against the verdict in the cities of Basel, Zurich and Geneva. In Basel, on August 10, 1927, the original execution date for Sacco and Vanzetti, a demonstration took place on Barfüsserplatz . With over 12,000 participants, it is still one of the largest in the history of the city. On the same evening a bomb destroyed a tram house on Barfüsserplatz. A tram driver and one other person died, 14 people were injured. The case is considered unsolved.

The International Red Aid , the mid-20s in many states offshoot, had coordinated worldwide protests with its member organizations. In Germany, Kurt Tucholsky - published in the Weltbühne on April 19, 1927 - called on the US ambassador to obtain at least a speedy pardon for the two trade unionists.

Call for revision

The Defense Committee now focused its efforts entirely on setting up a committee of inquiry. Although this request was made by over sixty professors and lawyers across the country to the Governor of Massachusetts, Alvan T. Fuller , there was a broad front against such efforts among the upper and middle classes .

Opponents have voiced concern that the reputation of the institutions of Massachusetts could be damaged by a revision committee: It would shamefully so act as if the "courts are incapable of Massachusetts, to speak fairly and honestly in criminal trials". Vanzetti wrote in a letter: "You must kill us to save the dignity and honor of the Commonwealth ."

Another reason was resentment against foreigners and dissenters, which, according to the defense, shaped the whole process. For many, the undisputed fact that Sacco and Vanzetti were immigrants, refugees and anarchists was enough to deny them civil rights per se . Quoting from a letter to the editor to the New Republic : “I say Judge Thayer was right when he found her guilty of murder, with or without evidence, in order to get rid of her [...] America is for Americans, not for them damn foreigners. "

A third argument against a revision was found in the protests themselves: one should not give in to the agitation of radical forces at home and abroad if one does not want to betray American values. Governor Fuller was later quoted as saying, "The widespread support Sacco and Vanzetti enjoyed abroad proved that there was a conspiracy against US security."

In fact, a petition initiated by Jackson found between 750,000 and a million supporters worldwide. Glued together and wrapped around a stick, the heavy roll with the signed petitions was delivered to the governor's office with the attention of the newspapers.

Vanzetti's petition for clemency

On Thompson's advice, Vanzetti wrote a pardon to the governor of Massachusetts. He had previously refused to take such a step. Now he saw it as the only chance to save his life. The application, co-designed and revised by the lawyers, was based on the argument that Judge Thayer was proven to have been biased. His hostility towards Sacco and Vanzetti shaped the process and the decisions on the appeals. Affidavits attached to the application should support this view.

Several journalists stated that Thayer had disparagingly talked to them about the defense attorneys ("damn fools"; about Moore: "long-haired anarchist from the West") and seemed to express his whole attitude that "the jury was there for this To condemn men ”. The humorist Robert Benchley reported in his affidavit of a chance encounter with Thayer in a golf club. There Thayer told a friend about the pressure exerted on the court by a “horde of salon radicals” and that he, Thayer, “would show them and get these guys on the gallows” and he “would be happy to have a dozen of them too Would hang up radicals ”because no Bolshevik could intimidate him.

To Vanzetti's annoyance, Sacco refused to sign the pardon. The psychiatrist Dr. Abraham Myerson, who then examined him, told of Sacco’s views: “He wants freedom or death. He was not guilty of any crime and did not want to spend the rest of his life in prison. ”Drawing attention to the natural law of self-preservation, Sacco replied that nature did not extend into his cell. Sacco also said to others who spoke to him in this matter that his death would also redeem his suffering wife. In his essay on Sacco’s insanity , Dr. Ralph Colp stated that Sacco only recovered after the death sentence was announced: “As soon as he realized that he was going to die, Nick Sacco became more cheerful than he had ever been since his arrest. The integrity of his personality reached a climax when he rejected the requests of Vanzetti and all of his friends and declined any further communication with the authorities. "

Vanzetti's petition for clemency was handed over to the governor on May 4, 1927, without Sacco’s signature.

Fuller's Commission

As governor, Fuller had the right to overturn judgments made in his state for grace or legal reasons. Faced with Vanzetti's pardon and ongoing protests against the verdict, Fuller decided to set up a committee of inquiry. The Defense Committee was hopeful and canceled planned demonstrations for the time of the investigation.

The president of Harvard , Abbott Lawrence Lowell , was announced as chairman of the three-member Commission on 1 June 1927th Although he - like the other two members - had no experience of criminal proceedings, he was held in high regard and trusted. The fact that he advocated a rigid policy against immigrants in the Immigration Restriction League for years and wanted to introduce a numerus clausus for Jews at Harvard in 1922 was initially ignored.

The Lowell Commission officially began its work on July 11, 1927. The execution planned for that day was therefore postponed to August 10, 1927. Sacco and Vanzetti were placed in Charlestown Prison from June 30, where the execution was to take place. During the questioning of the witnesses, Lowell tried unsuccessfully to refute Sacco's alibi through new speculations. Only about two weeks after the start of the investigation, on July 27, the three members came to the conclusion in their report that there was no doubt about the guilt of the defendant Sacco and, overall, also no doubt about the guilt of Vanzetti (“On the whole , we are of the opinion that Vanzetti was also guilty beyond a reasonable doubt ”). Late in the evening of August 3, Fuller announced his decision, based on this report, not to pardon Sacco and Vanzetti or to grant a new trial.

The report of the commission, which was published only days after Fuller's decision, was received with satisfaction by the general public and in most newspapers. Only a few critical voices pointed to alleged inadequacies. In an open letter to Lowell , the writer John Dos Passos asked : "Did the prosecution's evidence appear so weak to the committee that it had to back it up with new conclusions and assumptions of its own?" but make the previous decisions respectable. In fact, the report confirms Judge Thayer's decisions by drawing on testimony that was not heard in court because of their untrustworthiness.

The inconsistent conclusion that there is no doubt about Vanzetti's guilt on the whole (for example "by and large") is indicative of the weak evidence, despite great efforts : the guilt of a defendant must be proven absolutely beyond any doubt in order to obtain a guilty verdict and thus justifying the death penalty.

Last rescue attempts

Thompson decided to have a new lawyer bring in the final appeals so as not to unnecessarily provoke the decision-makers. Arthur H. Hill, a respected lawyer from Boston , filed a motion for a stay of execution on August 6th. The application was rejected.

On the same day, the lawyer Michael Musmanno tabled the seventh and final additional motion for a retrial, on which Judge Thayer again had to decide. The content of the motion was Thayer's alleged bias, which made a fair trial impossible. Judge Thayer refused to negotiate the allegation of his own bias and the request for the judgment to be set aside, as he would not have the legal authority to decide on such motions after the judgment had been pronounced.

Requests for retrial and postponement of execution to the Supreme Court were also denied. The defense appealed against these decisions on August 9th. Judge George Sanderson's decision on whether the appeal was admissible was due to be made on August 11th. The execution of the judgment, scheduled for August 10 at midnight, was nevertheless prepared as planned. It was only at 11:23 p.m. that the execution, which had been awaited with tension and horror worldwide, was canceled: Fuller ordered a twelve-day delay to await the decision of the courts.

The appeal to the Supreme Court was formally admitted, but its content was rejected on August 19: the alleged bias of the trial judge no longer needs to be investigated, since requests for retrial that would be brought in after the verdict had been pronounced would in any case be too late. Attempts to persuade US Supreme Court judges to postpone the execution of the sentence also failed.

In parallel with the desperate efforts of the defense in the courts, the wave of public protest reached a new high. The largest demonstrations in America took place in New York , where hundreds of thousands followed the call to strike and left their jobs. Otherwise, there were mostly only uncoordinated and comparatively small protests by workers in the USA because government representatives threatened strikers and protesting foreigners with severe consequences. But many American intellectuals now also took part in rallies with publicity.

Outside the United States, there were large-scale strikes and demonstrations in Paris, London, Belfast, Moscow, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Bucharest, Rome, Madrid and other cities. There were also demonstrations for Sacco and Vanzetti in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Japan, China, North and South Africa, Mexico and Central and South America. In addition, hundreds of thousands of requests for clemency arrived from all over the world, signed by politicians, writers and scientists, among others. A week and a half before the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, the Red Aid of Germany published a documentary on the case on August 12, 1927, which was published for the last time in German-speaking countries to fight for the pardon of the two convicts.

In addition to the generally peaceful demonstrations, bomb attacks unsettled the American public: attacks were carried out on a church, on railways, on a theater and on the apartments of a mayor and a jury member of the trial. None of the assassins was investigated.

The fronts seemed more hardened than ever: "The fear for the security of the existing order led to hatred of those who criticized this order, and ultimately to the opinion that a pardon would mean a strategic defeat."

Enforcement of judgment

On August 22, the day of his execution , Sacco said goodbye to his wife Rosina. A few days earlier, Vanzetti's sister Luigia had arrived from Italy and she was now saying goodbye to her brother. Both women went to see Governor Fuller that evening and pleaded for mercy. The defense had also made last-minute efforts to convince Fuller to delay. Then, about an hour before the scheduled execution, Fuller definitely decided against the stay.

Celestino Madeiros, who had been sentenced to death for the murder of a bank clerk and whose execution had also been postponed for further investigation after his confession, was the first to enter the execution chamber.

Sacco followed shortly after his death. He said goodbye to his wife, child and friends. Because his body had lost water and salt after the hunger strike he held for the past thirty days, he was put on a higher tension . At 12:19 a.m., he was pronounced dead.

When Vanzetti entered the chamber a short time later, he shook hands with the guards and the prison director and reaffirmed his innocence to the witnesses to the execution. He also said, "I want to forgive some people for what they are doing to me." His death was determined at 12:27 am.

International reactions

The news of Sacco and Vanzetti's deaths was met with anger and sadness by people around the world. At Union Square in New York were to a report in the New York World fifteen thousand people gathered, shouting after the news of his death, wept and fainted.

Outside the USA, the anger over the execution and on America erupted in sometimes wild protests. In Geneva estimated five thousand demonstrators marched through the streets. As in other cities, there was aggression against American facilities, shops, cars and cinemas that played American films. In Paris, the US embassy had to be protected with tanks. On the eve of the execution, 40 communist, socialist, trade union, anarchist, pacifist and humanist organizations called for demonstrations in 24 districts in Berlin alone. Thousands took part, including entire company staff. The day after the execution, mourning rallies took place across Germany, some of which were among the largest in recent years. Workers' meetings were held in most of the mines in the Ruhr area. In Berlin, around 150,000 people followed the KPD's call for one of the largest demonstrations in the Weimar Republic . The KPD chairman Ernst Thälmann gave the speech against the murder of Sacco and Vanzetti in the Berlin Lustgarten, which was printed on August 25, 1927 in the party newspaper Die Rote Fahne . There were also demonstrations in other German cities, for example in Stuttgart with a two-hour torchlight procession. In riots on the sidelines of the demonstrations, for example in Hamburg, there were a total of six deaths in Germany. Strikes and wild demonstrations also broke out in England, Scandinavia, Portugal, Mexico, Argentina, Australia and South Africa.

funeral

The embalmed corpses were laid out in a funeral home from Thursday, August 25, and were visited by thousands of people. The funeral procession took place on Sunday under strict conditions from the authorities and police supervision. In addition to Luigia Vanzetti, Rosina and Dante Sacco, thousands of people took part in the approximately twelve-kilometer funeral march to the cemetery. On the way, the Defense Committee participants put on arm bows that had been prepared by the Defense Committee with the imprint Remember justice crucified! August 22, 1927 ("Remember Justice Crucified") to demonstrate against the execution. The mounted police then used batons to disperse the crowd.

At the cemetery, the bodies of Sacco and Vanzetti were cremated in the crematorium , although this did not meet the wishes of the deceased or their relatives. Both Luigia and Rosina deliberately stayed away from the ceremony organized by the Defense Committee in the chapel.

The ashes of both men were mixed up and divided into three urns. The Defense Committee handed one urn each to Rosina Sacco and Luigia Vanzetti.

Reviews of the case

Question of guilt

Even decades after the executed verdict, a large number of speculations arose about the case, particularly the guilt or innocence of Sacco and Vanzetti. Up to the present day there have been numerous journalistic attempts to rework the complex issue in order to arrive at a satisfactory result. Three main currents can be identified, all of which to this day have a more or less large following:

- Sacco and Vanzetti are both guilty, the process can be assessed as fair and the criticism has mostly to do with "left propaganda" to make the convicts appear as martyrs. The reasoning for this thesis is based on the evidence of the trial and the results of the commission appointed by Governor Fuller. The book Sacco-Vanzetti: The Murder and the Myth by Robert H. Montgomery , published in 1960, is one of the few publications that hold this view .

- Partly to blame: Sacco is guilty, Vanzetti is not, but he was probably involved in planning the attack. This portrayal was particularly boosted by the books by the writer Francis Russell ( Tragedy in Dedham , 1962, and The Case Resolved , 1986): Among other circumstantial evidence, he cites the claim that the leading anarchist Carlo Tresca had confirmed Sacco's guilt before his death ("Sacco was guilty, Vanzetti was not guilty"), as well as new ballistic tests.

- Both are innocent and were victims of the inflammatory mood at the time against politically dissenters and foreigners. Representatives of this representation refer, among other things, to xenophobic statements by the judge and the jury speaker Ripley (“You should definitely hang them up!”), The many alibi witnesses and the assumption that the few pieces of evidence were forged. As early as 1927, Felix Frankfurter's book The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti: A Critical Analysis for Lawyers and Laymen appeared , in which this American lawyer gave Judge Thayer and the public prosecutor a devastating testimony to their work. This was followed by Osmond K. Fraenkel, The Sacco-Vanzetti Case (1931) and G. Louis Joughin and Edmund M. Morgan, The Legacy of Sacco and Vanzetti (1948). In her 1977 book Justice Crucified. The Story of Sacco and Vanzetti (German 1979) examined Roberta Strauss-Feuerlicht the case in the context of the Puritan tradition of America.

The deadly "Kugel III", which supposedly came from Sacco's Colt, plays an essential role in all theories. In 1961, at the instigation of Francis Russell, ballistic tests were carried out on Sacco's weapon again after the corresponding tests of 1920/21 had not provided any clear evidence. In 1961, according to the protocol, the tests seemed to indicate ("suggested") that it could have been the murder weapon. This is countered by another party that on the one hand the rust accumulated over the years would distort the result, and on the other hand there are indications that the ball on which the tests were based was exchanged at the time to make Sacco appear guilty.

Rating by Michael Dukakis

In July 1977 - 50 years after the execution - Michael S. Dukakis , Democratic Party politician and then Massachusetts Governor , rated the trial as unfair:

“Today is the Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day. The atmosphere of their trial and appeals were permeated by prejudice against foreigners and hostility toward unorthodox political views. The conduct of many of the officials involved in the case shed serious doubt on their willingness and ability to conduct the prosecution and trial fairly and impartially. Simple decency and compassion, as well as respect for truth and an enduring commitment to our nation's highest ideals, require that the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti be pondered by all who cherish tolerance, justice and human understanding. "

“Today is Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day. The atmosphere of their trial and revisions was steeped in prejudice against foreigners and hostility to unorthodox political views. The behavior of many of the officials in this case raises serious doubts about their willingness and ability to conduct the persecution and trial in a fair and impartial manner. Simple decency and compassion, as well as respect for the truth and an ongoing commitment to the highest ideals of our nation, require that the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti be remembered by all who value tolerance, justice and human understanding. "

The case in cultural reception

The world-shaking events surrounding the two people who were executed have inspired a large number of writers, dramaturges, composers, musicians, visual artists and other cultural workers to this day. In works of the most varied of art genres, Sacco and Vanzetti often become tragic, in some modern interpretations also tragic-comic symbolic figures, who are helplessly at the mercy of the arrogance and injustice of the elites as unadjusted idealists from the lower class.

literature

In the literature that emerged during or in the years after the trial, protest and solidarity in the fate of the two workers dominate. John Dos Passos wrote a book in 1927 called Facing the Chair: The Story of the Americanization of two Foreignborn Workmen . Upton Sinclair , who, like many American intellectuals, was committed to Sacco and Vanzetti, worked on the case in his book Boston . Also under the impression of the execution, Kurt Tucholsky's poem 7.7 (“Seven years and seven minutes had to bleed two workers' hearts”) was written in 1927 . The Chinese writer Ba Jin processed his impressions in his short story collection The Electric Chair in 1932 . In the story On the Way to the American Embassy , published in 1930, Anna Seghers describes the events surrounding a demonstration against the condemnation of Sacco and Vanzetti. The American writer Howard Fast edited the story of Sacco and Vanzetti in his 1953 novel The passion of Sacco and Vanzetti, a New England legend , published in German translation in 1955 under the title Sacco and Vanzetti - A legend from New England in the East Berlin-based Dietz publishing house .

In his debut novel Sacco And Vanzetti Must Die , published in 2006, Mark Binelli finds a seemingly provocative approach in that the disturbing story is linked with invented and weird-comic elements: The anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti - with reference to Laurel and Hardy - close anarchist slapstick comedians. Years earlier, the playwright Louis Lippa had implemented a similar idea (see theater and film).

Theater and film

Probably the first film adaptation of the case took place in 1927: Alfréd Deésy directed the Austrian silent film In the Shadow of the Electric Chair . The film Winterset (1936) is based on the case , as is the play Decembertag by Maxwell Anderson on which the film is based .

In 1928 Erich Mühsam had the drama Staatsräson (a memorial to Sacco and Vanzetti) performed in Germany during the Weimar Republic .

The American television broadcaster NBC showed The Sacco-Vanzetti Story (script: Reginald Rose , director: Sidney Lumet ) as part of the series Sunday Showcase in 1960 . The two-part television game brought the case new attention, but was criticized as not being true to the facts.

Three years later - in 1963 - on behalf of WDR , the director Edward Rothe staged the script from Reginald Rose, adapted into German by Hartwig Schmidt (based on court minutes) in the documentary play The Sacco and Vanzetti case for German television (with Robert Freitag in the role of Saccos and Günther Neutze as Vanzetti).

In 1967 Paul Roland filmed The Sacco and Vanzetti Affair in Belgium.

In 1971 the Italian-French feature film production Sacco and Vanzetti (directed by Giuliano Montaldo ) was released. The film is the most well-known dramaturgical processing of the case today and also uses rarely shown archive material from demonstrations for Sacco and Vanzetti from various newsreels of the 1920s. Ennio Morricone contributed the soundtrack .

In his play Sacco & Vanzetti - A Vaudeville (premiere 1999), the American playwright Louis Lippa processed the judicial murder into a bitterly ironic farce: Two hours before their execution, Sacco and Vanzetti play the story of their conviction in the style of an American numbered revue of the time. In 2005 the play had its German-language premiere as Sacco & Vanzetti: An Anarchist Comedy .

In 2004, a two-part television film about the case was made in Bulgaria.

In 2006 the first cinema documentary about Sacco and Vanzetti was shot under the direction of Peter Miller ; a German subtitled version will be available from 2017.

The case of Sacco and Vanzetti is also referred to in the film First Impact, about the later director of the FBI Flynn .

music

The American folk singer Woody Guthrie created the cycle Ballads of Sacco & Vanzetti in 1945 , which he recorded for Folkways in 1946/47 . The album wasn't released until 1960, as Guthrie himself wasn't happy with the result. In addition to Guthrie's eleven ballads, it also contains a song by Pete Seeger from 1951. As the lyrics of the song , Seeger used Nicola Sacco's farewell letter to his son Dante ( Sacco's Letter To Son ).

The song Here's to You (text: Joan Baez , composition: Ennio Morricone ), which has become world-famous as a kind of hymn , comes from the soundtrack of the Montaldo film Sacco and Vanzetti . The last two lines of the four-line stanza repeated several times are based on a statement Vanzetti made about three months before the execution: “The last moment belongs to us, that agony is our triumph!” (“The last moment will be ours, this agony is our triumph!”) It is the tenth and final track on the 1971 long-playing record with various other ballads on the subject, also sung by Joan Baez. This song was later published in the version by Georges Moustaki under the title La marche de Sacco et Vanzetti in French. The Israeli singer Daliah Lavi adapted a trilingual version of the Baez / Morricone title in English, French and German in 1972. Also from 1972 is a more complex German version of the song with the same melody, but more detailed text by the songwriter and lyricist Franz Josef Degenhardt . The Angela mentioned in this adaptation refers to Angela Davis . The German punk band Normahl covered the Degenhardt text on their album Blumen im Müll in 1991 .

To the present day, there are other cover versions of the named titles, adaptations and interpretations of the case and the people of Sacco and Vanzetti in different languages and musical styles by different interpreters.

In almost every musical treatment of the case and the characters, Sacco and Vanzetti are portrayed, directly or indirectly, as victims of judicial murder and political martyrs .

Visual arts

The painter, draftsman and caricaturist George Grosz created the drawing Sacco and Vanzetti in 1927 .

The painter Ben Shahn dedicated the tempera painting The Passion of Sacco & Vanzetti to the convicts in 1931/32, interpreting their funeral in the style of American social realism , and a little later a mosaic on a wall at Syracuse University in New York State .

The artist Siah Armajani designed the Sacco and Vanzetti reading room in 1987 . The installation, designed for public use, was an integral part of the Museum of Modern Art in Frankfurt am Main for several years.

literature

Listed chronologically according to the date of the first edition.

- Bartolomeo Vanzetti (autobiography): The Story of a Proletarian Life . Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee, Boston 1923; Reprint (booklet): Kate Sharpley Library , London 2002, ISBN 1-873605-92-7 .

- Felix Frankfurter : The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti: A Critical Analysis for Lawyers and Laymen . Little, Brown and Company, Boston 1927; New edition: William S. Hein & Co., New York 2003, ISBN 1-57588-805-X .

- Eugene Lyons : The Life and Death of Sacco and Vanzetti . First edition, International Publishers, New York 1927.

- Augustin Souchy : Sacco and Vanzetti . Revised edition (of the writing: Sacco and Vanzetti - 2 victims of American dollar justice . Verlag Der Syndikalist , Berlin 1927), Verlag Freie Gesellschaft, Frankfurt am Main 1977, ISBN 3-88215-002-5 .

- Nicola Sacco (and Bartolomeo Vanzetti): The Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti . First edition, published by Viking Press, New York 1928.

- Osmond K. Fraenkel: The Sacco-Vanzetti Case . First edition, Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1931; Reprint: Verlag Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1971, ISBN 0-8462-1402-4 ; Reprinted for: The Notable Trials Library, with a recent introduction by Alan Dershowitz, Gryphon Editions, Inc., Birmingham 1990.

- Luigi Botta (prefazione di Pietro Nenni): Sacco e Vanzetti: giustiziata la verità . Edizioni Gribaudo, Cavallermaggiore, 1978 ( free downloads ).

- Herbert B. Ehrmann: The Untried Case: The Sacco-Vanzetti Case and the Morelli Gang . First edition, published by The Vanguard Press, New York 1933.

- G. Louis Joughin, Edmund M. Morgan: The Legacy of Sacco and Vanzetti . With a foreword by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York 1948.

- Herbert B. Ehrmann: The Untried Case: The Sacco-Vanzetti Case and the Morelli-Gang . Completed new edition, with a new foreword by Joseph N. Welch and a new introduction by Edmund M. Morgan, published by The Vanguard Press, New York 1960.

- Francis Russell: Tragedy in Dedham - The Story of the Sacco-Vanzetti Case . First edition, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York 1962; unchanged new edition 1971, ISBN 0-07-054342-9 .

- Hasso Grabner: Judicial murder in Dedham . German military publisher, Berlin 1962.

- David Felix: Protest: Sacco-Vanzetti And The Intellectuals . First edition, Indiana University Press, Bloomington / Minnesota and London 1965.

- Robert H. Montgomery: Sacco-Vanzetti: The Murder and the Myth . Western Islands Publisher, Boston 1965, The Americanist Library, ISBN 0-88279-003-X .

- Herbert B. Ehrmann: The Case That Will Not Die - Commonwealth vs. Sacco and Vanzetti . First edition, published by Little, Brown and Company, Boston and Toronto 1969; New edition in the United Kingdom, Verlag WH Allen & Company Ltd., London 1970, ISBN 0-491-00024-3 .

- Nicola Sacco (and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, among others; Ed .: Marion Denman Frankfurter, Gardner Jackson): The Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti . Supplemented reprint, with a new foreword by Richard Polenberg, Verlag Penguin Books Ltd., New York 1971, Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics, ISBN 0-14-118026-9 .

- Roberta Strauss Feuerlicht: Justice Crucified. The Story of Sacco and Vanzetti . McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York 1977, ISBN 0-07-020638-4 . (According to the New York Times review, "the most comprehensive and convincing account of the 'Sacco and Vanzetti' case to date".)

- Frederik Hetmann : acquittal for Sacco and Vanzetti . 1st edition, youth literature, Signal-Verlag, Baden-Baden 1978, ISBN 3-7971-0188-0 .

- Roberta Strauss-Feuerlicht: Sacco and Vanzetti . German speaking Edition (of the original edition from 1977), translated by Heinrich Jelinek, Europa Verlag, Vienna / Munich / Zurich 1979, ISBN 3-203-50702-1 .

- Eugene Lyons: Sacco and Vanzetti . German speaking Edition (of the original The Life and Death of Sacco and Vanzetti from 1927), Unionsverlag, Zurich 1981, series uv 6, ISBN 3-293-00016-9 .

- Francis Russell: Sacco & Vanzetti: The Case Resolved . 1st edition, Harper & Row, New York (et al.) 1986, ISBN 0-06-015524-8 .

- Helmut Ortner: Foreign enemies: the Sacco & Vanzetti case. 1st edition. New edition (the 1988 edition Two Italians in America ), Steidl-Verlag, Göttingen 1996, Steidl-Taschenbuch Nr. 76. ISBN 3-88243-430-9 .

- Paul Avrich : Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background . Print edition from Princeton University Press, Ewing, New Jersey 1991. Paperback edition 1996. ISBN 0-691-02604-1 .

- A Probabilistic Analysis of the Sacco and Vanzetti Evidence. On the subject of evidence in criminal proceedings. John Wiley and Sons, 1996. ISBN 0-471-14182-8 .

- Bruce Watson: Sacco & Vanzetti, The Men, the Murders, and the Judgment of Mankind . Viking Verlag, Published by the Penguin Group, New York 2007. ISBN 978-0-670-06353-6 .

- Matteo Pretelli: Sacco, Ferdinando. In: Raffaele Romanelli (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 89: Rovereto – Salvemini. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2017.

- Matteo Pretelli: Vanzetti, Bartolomeo. In: Raffaele Romanelli (Ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 98: Valeriani-Verra. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2020.

Web links

- The Trial of Sacco and Vanzetti 1921 ( Memento from 23 August 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Page on the process with further links (English)

- Nunzio Pernicone: About the Sacco-Vanzetti case (English)

- Nick Brauns: Sacco and Vanzetti Presentation of the case for the newspaper Junge Welt

- Petition by Kurt Tucholsky against the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti

- Sacco and Vanzetti in the Internet Movie Database . Film by Peter Miller, 2006, German OmU 2017

- Trailer of the documentary by Peter Miller (English)

- Katrin Brand: May 5th, 1920 - Arrest of N. Sacco and B. Vanzetti WDR ZeitZeichen on May 5th, 2020. (Podcast)

Individual evidence

The main sources were the books The Case That Will Not Die by Ehrmann, Tragedy in Dedham by Russel and Justice Crucified - The Story of Sacco and Vanzetti by Strauss-Feuerlicht, the latter in the German translation Sacco and Vanzetti . In addition to their own research, the authors rely on the trial protocol, published as The Sacco-Vanzetti Case: Transcript of the Record of the Trial of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in the Courts of Massachusetts and Subsequent Proceedings, 1920–1927 by Henry Holt, New York , 1928 and 1929 (Supplemental Volume) , reprinted by Paul P. Appel, New York, 1969.

- ^ Sacco & Vanzetti: Proclamation

- ↑ Lt. its statement in the process protocol, p. 5231, see also in Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 32.

- ↑ Cf. Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 30 ff. And Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , pp. 78–82.

- ↑ Cf. Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 34 ff. And Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , pp. 73–78, 82.

- ↑ Vanzetti in his autobiography, p. 18 f.

- ↑ See process protocol, p. 1924; For deportation, see Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 172.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 169 f.

- ↑ Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 168.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 128 f.

- ↑ Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 147, citing the "Report upon the Illegal Practices of the United States Department of Justice by Twelve Lawyers", Washington, DC, 1920, p. 65. - This report lists the large number of violations of the law which it came in the wake of the Palmer raids, and was worked out as an argument against the proposed 'law against riot in peacetime' by the Senate.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 137 f .; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , pp. 84 f.

- ↑ Cf. Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 146 f. Max Lowenthal, The Federal Bureau of Investigation , New York, 1950, p. 84 and Robert K. Murray, Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria , New York, 1964, are cited , P. 196. A summary of the Palmer raids is also available in Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , p. 87.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 154, Murray, Red Scare , p. 211.

- ↑ Cf. New York Times , November 8 and 9, 1919, as well as the “Report upon the Illegal Practices of the United States Department of Justice by Twelve Lawyers”, p. 18, quoted in Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 148 ff.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 172 f .; Ehrmann, The Case That Will Not Die , p. 47 ff .; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , p. 88.

- ↑ Cf. Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , p. 49 f.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 25 f .; detailed summary of the testimony in Ehrmann, The Case That Will Not Die , pp. 19–41; also in Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , pp. 29-48.

- ↑ Cf. Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 27–29, 175 ff .; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , pp. 43-46, 53; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , pp. 54-64.

- ↑ See process protocol p. 3387, p. 3388 f .; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 181 ff .; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , p. 54 f .; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , pp. 64-68.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 181; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , pp. 70 f .; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , pp. 94, 69 f.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 181, 183; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , pp. 58-61.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 184 f., 206 f .; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , p. 107.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 183 f., 187; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , pp. 73, 77; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , p. 97.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 187 ff .; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , pp. 74 f., 77-81.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 196, 200; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , pp. 99-105.

- ↑ Process protocol, supplementary volume, p. 332; quoted in Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 201.

- ↑ Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 204.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 211 f .; Felicani, Reminiscences , pp. 68-70, 110; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , p. 108 f.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 213, 218; Ehrmann, The Case That Will Not Die , p. 156.

- ↑ Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 223 f .; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , p. 460; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , p. 127.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 225 f .; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , p. 69.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 229 f.

- ↑ See The Atlantic Monthly , March 1927, p. 415.

- ↑ process protocol, p. 3514; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 233.

- ↑ process protocol, p. 815 f., P. 5235; Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 233–236.

- ↑ process protocol, p. 854; see Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 237–239.

- ^ Process protocol, p. 3527, quoted in Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , p. 398.

- ^ Process protocol, pp. 896, 3642; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 242; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , p. 270.

- ↑ See process protocol, p. 2254; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 243.

- ↑ process protocol, p. 3642 f., 5084; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 243; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , p. 265 f.

- ↑ See Ehrmann, The Case That Will Not Die , pp. 251-277, 283 f .; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 244.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 247 f.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 250 f.

- ↑ process protocol, p. 2023; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 255 f.

- ↑ Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 258.

- ↑ See process protocol, pp. 1737, 1867 ff .; Strauss-Feuerlicht, pp. 264, 272 f .; The Atlantic Monthly , March 1927, pp. 418 f.

- ↑ process protocol, p. 2237; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 287.

- ↑ process protocol, p. 2239; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 287 f.

- ↑ process protocol, p. 2265 f .; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 289 f .; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , p. 388; Russel, Tragedy in Deham , p. 211 ff.

- ↑ process protocol, p. 4904 f .; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 349.

- ↑ Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 300.

- ↑ a b Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 300 f.

- ↑ Process protocol, p. 3602 f., Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 318.

- ↑ "If the sworn jury came to the conclusion that the murder of Parmenter and Beradelli was the only true and logical explanation [for Saccos and Vanzetti's false information during the first interrogations in Brockton, note], I should now, by repealing their verdict, explain that they should not have come to this conclusion? "Trial protocol, p. 3523.

- ↑ Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 301 f.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 320 f.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 321; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , p. 276 f.

- ↑ Process protocol, p. 3642 f.

- ↑ process protocol p. 3703; Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 321.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 217 f.

- ↑ Quoted by the author Upton Sinclair, see Francis Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , p. 17, and Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , p. 402 f.

- ↑ See Strauss-Feuerlicht, p. 306 f .; Ehrmann, Case That Will Not Die , p. 402 f .; Russel, Tragedy in Dedham , pp. 108, 110 f.