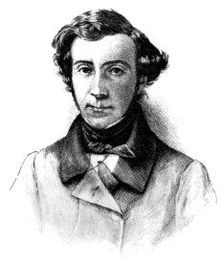

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles-Henri-Maurice Clérel de Tocqueville [ alɛkˈsi ʃaʀl ɑ̃ˈʀi mɔˈʀis kleˈʀɛl dətɔkˈvil ] (born July 29, 1805 in Verneuil-sur-Seine , † April 16, 1859 in Cannes ) was a French publicist , politician and historian . He is considered the founder of comparative political science .

Life

De Tocqueville was born the third son of Hervé Bonaventure Clérel de Tocqueville and Louise Le Peletier de Rosanbo (a granddaughter of the statesman Malesherbes ). He spent his childhood in Verneuil-sur-Seine , where his noble father, like his mother, became mayor. From the age of ten, his father served successively in the prefectures of Angers , Beauvais , Dijon , Metz , Amiens and Versailles , so that de Tocqueville mainly grew up with his mother. His intellectual mentor at the time was the Abbot Louis Lesueur .

In 1820 he moved to his father in Metz , where he completed his studies in philosophy and rhetoric at the Collège Royal there in 1823. During this time he fathered an illegitimate child with a servant.

After Tocqueville had moved to Paris, where his studies of jurisprudence had finished, he was in 1826 investigating judge in Versailles . In the following years he made the acquaintance of Gustave de Beaumont , with whom he later traveled to America, and with the Englishwoman Mary Motleys (1826), with whom he married in 1835, which remained childless. He heard François Guizot's history lectures at the Paris Sorbonne (1829/1830) and received his doctorate in Versailles in 1830.

In 1826 he was commissioned by the government to study the legal system and the penal system in the United States of America . Tocqueville toured the US with his friend Gustave de Beaumont . For their work Du système pénitentiaire aux États-Unis , the two received a prize from the Académie française . The famous main work De la démocratie en Amérique (two volumes, Paris 1835/1840) resulted from the trip to America (from May 1831 to February 1832) and the experiences made there . The first volume appeared on January 23, 1835 with an edition of less than 500 copies. A second edition was published in June of the same year. The eighth edition, which appeared both in Paris in 1840 and in a translation by Henry Reeves in London , finally also contained the second volume of his investigations.

Between 1839 and 1848 Alexis de Tocqueville was a member of the moderate opposition . He opposed the Guizot government, which he believed had transformed French society into a gigantic apolitical stock corporation. Striving for prosperity alone, he explained, did not make good citizens. Together with his political friends, he unsuccessfully pursued the elimination of slavery - in the tradition of the generous, liberal French nobility. He played a special role before and during the February Revolution of 1848 : In a speech to the Chamber of Deputies on January 29, 1848, he warned of the coming events: “Do you notice - how do I say? - not the revolutionary storm that is in the air? ”From then on, this speech was regarded as prophetic, because barely a month later the monarchy under the“ citizen king ” Ludwig Philipp had perished in the revolution; Tocqueville himself left in his memoirs a realistic historical document about the events of the revolution, the provisional government and the suppressed June workers' uprisings of 1848. In this way he describes the effects of the civil war atmosphere on his neighbors, who served in the National Guard, and on had himself:

“When I spoke to them, I noticed with what alarming speed, even in a civilized century like ours, the most peaceful souls are preparing for civil wars, so to speak, and how the taste for violence and the contempt for human life suddenly spread there in this unfortunate time . The people I talked to were well-placed and peaceful craftsmen, whose gentle and somewhat soft habits were even further removed from cruelty than heroism. Still, they only thought of destruction and massacre. They complained that bombs, mines and trenches were not being used against the rebellious streets and they no longer wanted to show mercy to anyone. [...] as I continued on my way, I could not help but think about myself and marvel at the nature of my arguments, with which I had unexpectedly familiarized myself within two days with these ideas of merciless destruction and great severity that I had naturally lie so far "

He strove for a new relationship between the republic and the church and, in the constituent commission of the National Assembly after the revolution of 1848, urged the removal of the crippling centralization of political life in France. Here, however, he was so resigned that he no longer spoke up in the negotiations on this subject. “In France there is only one thing that you cannot create, namely a free government, and only one thing you cannot destroy, namely centralization,” he wrote in the 2nd part (Chapter XI) of his memoirs. An attack on the centralized administration was "the only way to bring a conservative and a radical together." The center of Tocqueville's political activity was (according to his own conviction of the importance of the subject) the advancement, promotion and ordering of the conquest and colonization of Algeria . The answer to his question "How can you prevent mediocrity and also produce or promote great things in egalitarian societies?" Was colonialism for him .

Two long trips to Algeria, several commission reports in the National Assembly and a number of speeches testify to Tocqueville's unshakable conviction: Algeria should become a French colony with a French class of owners and a primarily indigenous, serving class of non-equals.

After the February Revolution of 1848, he fought socialism and voted with the conservatives; he was one of their leading representatives. As a member of the Legislative Assembly, he helped shape the new constitution. In 1849 Tocqueville took over the Foreign Office, but resigned when Louis Napoléon , later Napoléon III, seized power in a coup. During the coup d'état on December 2, 1851, Tocqueville was arrested, but released on the intervention of Napoleon. Bitter about the loss of freedom and liberal relationships, he withdrew into private life. Now he wrote the souvenirs , which - full of sarcastic remarks about his contemporary parliamentary colleagues - did not appear until long after his death at his request. This was followed by his second major work L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution , the first volume of which appeared in 1856.

About Democracy in America (1835/1840)

De la démocratie en Amérique describes, among other things, democracy in the context of political society. The book received the Prix Montyon of the Académie française in 1836 , of which Tocqueville became a member in 1841, and is still treated today at universities. In his analysis of American democracy, he worked out the reasons for the way democracy works in the USA. He shows the dangers of democratic governance that can lead to “tyranny of the majority” and describes how the American Constitution and its constitutional life counteracted this danger through decentralization and active participation of the citizens (Volume 1). In the second volume of the work he identifies yet another danger that is inherent in democracy for him: the omnipotence of the government, which deprives the citizens of their own initiative, gradually weans them from independent action and thus degrades them to underage private individuals who only worry about their economic problems. Here, too, he shows how American democracy countered this danger: through decentralization, through the doctrine of well-understood self-interest, and through the influence of Christianity on the dominant behavioral standards.

About the relationship between freedom and equality

According to Tocqueville, the important institutions of the American Union all have a second, almost unintended side effect in addition to their problem-solving work: They educate the new generations of Americans to the civic spirit that prevailed in the young USA of the 1830s. You will receive the mœurs (morals), a sense of responsibility, initiative, a sense of order, willingness to interfere in public affairs, knowledge of democratic practice and a public political area in which the churches do not intervene directly: all of this is a matter of course for the United States. These things taken for granted, originally mostly a legacy of the Puritan founders, are made second nature to North Americans through the entire political and social life, especially through the institutions of local politics. Tocqueville describes this not without the ulterior motive that France and other European nations can learn from this part of the American example. So maybe they could develop democratic morals. The last chapter of this first volume of the Démocratie en Amérique examines the main reasons for the democratic republic in North America to survive and be stable. Tocqueville formulates the most important result of his considerations in the heading of a sub-chapter: "The laws contribute more to the preservation of the democratic republic in the United States than the geographic circumstances and the mœurs even more than the laws." In other words: The mœurs are for the stability of the American Union is more important than the written constitution, and they are also more important than the particular geopolitical position of the United States. In a footnote to the first paragraph of the sub-chapter so headed, Tocqueville reminds the reader of the description given in a previous chapter of what he calls mœurs . It says:

“I understand the term mœurs here in the sense that the ancients gave the word mores; So I apply it not only to the actual customs, which one could call cherished habits, but to the various concepts that people have, the different opinions that apply among them, and to the totality of ideas, which are the cherished habits form."

The mœurs or manners and habits thus describe the entire cosmos of ways of thinking, behaving, debating and interpreting a society; their way of describing public, economic and private affairs, their symbols and platitudes, their values and the resulting practice of human and civic behavior and action.

The second volume of De la démocratie en Amérique from 1840 deals more intensively with the fundamentals of state and politics . The mœurs remain the main subject of Tocqueville's investigations: just as the first volume examines and determines the effect of decentralized associations , local politics in the communities, jury courts, the federal division of the USA and other external factors on the citizenship of Americans in the 1830s The second volume also examines the more problematic mœurs of democracy to what extent the institutions of the American constitution keep the founding ideas of the United States alive . In particular, it describes the relationship between equality and freedom . Tocqueville sees no principles of equal importance in this, but speaks out clearly in favor of the primacy of freedom. According to Tocqueville, the formal equality of citizens that emerges in an enlightened state has various effects. First and foremost, the abolition of class rules and the equality of rights for all citizens create the space that a free individual needs at all. The loss of authorities and the independence of the people establish the love of freedom that characterizes democratic societies and their institutions. The critics see the greatest danger of a democratic order in the resulting anarchy . Tocqueville does not contradict this, but does not see it as the main problem of the principle of equality. Rather, he fears in his initial thesis of the fourth part of the second volume a creeping impairment of the freedom of the citizens. “Equality triggers two tendencies: one leads people straight to freedom and can also suddenly drive them into anarchy; the other leads them into bondage on a longer, more secretive, but more secure route . ”While a democratic state knows how to protect itself against anarchy, defending against the loss of individual freedom through equalization is more difficult, since this corresponds to the inclinations of the mass of citizens as well as the state.

For Tocqueville, the principle of equality tends to lead to a strong, centrally organized state, against which the individual can no longer defend himself. This gives rise to unlimited “popular violence”. The representatives of this power are gradually becoming aware of their violence and promote this position out of self-interest. The rulers can finally “manage all processes and all people”. For Tocqueville, this creates a transfer of responsibilities. By “governing” the leaders of these states understand not only the rule of the entire people, but also the responsibility for the well-being of each individual. They now also see their task in “guiding and advising citizens, and even making them happy against their will if necessary”. Conversely, individuals are increasingly transferring their personal responsibility to state power. Ultimately, Tocqueville fears slipping into bondage if equality becomes the only major goal.

The limits of equality and the end of compassion

In his study of pity, Henning Ritter encounters Tocqueville's notions of equality and states that the democratic feeling about the slavery that continues to exist in America has been suspended. Tocqueville perceives that the same person who is full of compassion for his fellow man becomes insensitive to their suffering as soon as they do not belong to his own kind. In this respect, slavery represents the enclave of a past social order, namely the aristocratic.

What applies to the slaves applies even more to the genocide carried out on the Indians , in which Tocqueville, according to Domenico Losurdo , sees "a divine plan, as it were," as he later found expression in the so-called Destiny Manifesto . Because Tocqueville blames the Indians for their downfall, especially since they were unable to present any title to the land they inhabit. According to John Locke , whom Tocqueville follows here, only that which is processed for use can become property. In this respect, Tocqueville speaks right at the beginning of the book of a "desert" that the Indians inhabit, as he later describes the land of the Indians in the same place as the "empty cradle":

“Although the vast land was inhabited by numerous indigenous tribes, it is fair to say that at the time of its discovery it was nothing but a desert. The Indians lived there, but they did not own it, because humans only acquire the land with agriculture and the indigenous people of North America lived on the hunting products. Their relentless prejudices, their indomitable passions, their vices, and even more perhaps their savage strength handed them over to inevitable destruction. The ruin of this population began on the day the Europeans landed on their coasts, it proceeded tirelessly and is now almost complete. "

With his book on democracy in America, Tocqueville found one of his strongest admirers in his Argentine contemporary Domingo Faustino Sarmiento , so that he expressly invokes him in his work Barbarism and Civilization : The Life of Facundo Quiroga from 1845. For Sarmiento it would have taken a Tocqueville and his method used in the America Book to adequately describe the Argentine Republic and its intended development. This admiration expresses what makes Tocqueville, in Domenico Losurdo's analysis, the representative of a “democracy for the master people”, as whom Sarmiento openly recognizes, since he only wants Europeans as settlers for Argentina instead of the indigenous population. For Sarmiento, as a reader of Tocqueville, it was clear that the Indian population of Argentina would have as little a future as the North American Indians compared to European claims.

European reception of On Democracy in America

To date, On Democracy in America is one of the most widely received works in the social sciences and is taught in many basic political science and sociology seminars. A number of core social science concepts can be traced back to the work. Tocqueville is one of the first critics of democracy to see the danger of “tyranny of the majority”. Especially in Volume 2 of the Démocratie en Amérique , Tocqueville also emphasizes that the pursuit of equality leads to uniformization under strong central authority. This incapacitates the citizens and makes them dependent on the actions of the respective government. The citizens would thus be weaned from acting independently. It cannot be overlooked that Tocqueville's considerations stem particularly from his French experience. He deepens these considerations in his second major work, L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution .

However, the dangers of tyranny and incapacitation in America are limited by a number of mechanisms. For example, there is no strong central government that could effectively carry out a dictatorship of the majority. Today, Tocqueville is associated with building European democracy . The Lisbon ruling by the German Federal Constitutional Court also points to the need for participatory democracy .

Conquest and colonization of Algeria

Tocqueville as a colonialist

As early as 1828, Tocqueville spoke out in favor of a military expedition to Algeria, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire . In 1833, after Algiers had been captured by French troops in 1830, he considered buying land there. He became an Algeria expert, which is particularly evident in his parliamentary career. While Tocqueville initially relied on private forces to settle Algeria, with the assimilation of the Arab population in mind, from 1841 he began to believe that only state policy would be able to completely conquer the country and bring it into French possession . Since the envisaged total conquest failed because not enough European settlers could be won, because the demographic situation in France, unlike in other European countries, stagnated, and Tocqueville no longer saw any chance of establishing an understanding with the Arabs, he came to from 1846 the conviction that the French occupation can only be guaranteed under constant control and disenfranchisement of the local population, i.e. that it should result in a kind of early apartheid regime .

Thoughts on Algeria (1841)

In his Travail sur l'Algérie , published in German for the first time in 2006 in the Small Political Writings under the title Thoughts on Algeria , Tocqueville shows himself to be a “vehement supporter of the policy of conquest” ( Harald Bluhm ).

Tocqueville writes that Algeria is so important to France because renouncing the conquest would mean "showing the world its certain decline" (p. 109). After the losses she suffered against England (see Seven Years' War in North America ), that was not responsible. First of all, it was a matter of defeating Abd el-Kader , who in the meantime had also copied and appropriated everything from the French military "what he needs to subjugate them (his compatriots)" (p. 116). The confrontation with him is now only possible in a fight, since other concepts such as the chance to play one against the other and to control everyone in this way, had not been used. Although he mentions that humanity and international law must be taken into account in the war to be waged (p. 120), he also has to admit that “this war (...) is not like any other”, “as everyone knows; all experiences from European battles are useless and often harmful ”(p. 128). Tocqueville argues with the advocates of mild practice:

“(…) People in France whom I respect, without agreeing to them, told me that it was bad to burn down crops, clear out storehouses and ultimately even take unarmed women and children into custody. I consider that to be tiresome necessities that every people who want to wage war against Arabs must bow to. "

He expressly recommends a trade ban for Arabs with the destruction of everything "that looks like a city" and devastation of the country, especially since "murderous ventures are sometimes indispensable and indispensable" (p. 120 f.). For the Army d'Afrique, locals, namely Zouaves , are important as mercenaries (p. 124) and French officers and men who have long served in Algeria. He finds the work of the officers admirable, but at the same time wonders “what should we do with a large number of such men when they return to us” (see, for example, General Lamoricière or Marshal Bugeaud ); because he is frightened by the thought that France will one day "be controlled by an officer of the African Army!" (p. 126 f.)

He advocates that colonization and conquest should be carried out at the same time, because this way one can count on the military commitment of the settlers themselves (p. 129), and wonders whether the conquered areas around Algiers should be protected by a fortification. In any case, the new land ownership of the settlers should be recorded in a land register to be introduced so that they are protected against the arbitrariness of the French authorities or the possible claims of their own military. Because it is about "a nation formed by Europeans", "which administers and secures the territory that we have conquered" (pp. 136-139). A governor-general, independent of Paris, should be appointed as head of administration, who should prevent abuse of power and arbitrariness so that Algeria becomes more attractive for settlers. Their personal freedom is to be guaranteed with the freedom of their property, because “the colonies of all European peoples offer the same picture. The role of the individual is greater there than in the mother country, and not less ”(p. 139). Therefore, "two very different legislations" should be set up "because there are two strictly separated societies" and the rules established for Europeans "only have to apply to them" (p. 157). In view of the situation in the early 1840s with four times as many soldiers as there were settlers, Tocqueville still sees a lot to be done (p. 162).

Regarding the ideas that Tocqueville developed about colonization, Seloua Luste Boulbina comes to the conclusion that although he was able to judge blacks, Arabs and French workers with political clarity, he remained deaf to anything social.

The old state and the revolution (1856)

Tocqueville's second major work, L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution , is an analysis of the French Revolution . The mœurs also play a leading role in this late work , although Tocqueville hardly ever uses the term in it. The described practical sense of the Americans, their mœurs brought in by the founding fathers and kept alive by the institutional order of the USA and passed on to the next generation , stand in tense contrast to the political conditions and the prevailing modes of thinking in France. In The Old State and the Revolution , Tocqueville shows that most of the institutions and constitutional rules that are commonly counted among the achievements of the revolution were not introduced by it, but existed before.

De Tocqueville also shows the distance to the Great Revolution that already catches the eye in his America work. Tocqueville welcomes and affirms the results of the revolution, he admires the generosity of the first revolutionaries, but he is convinced that the political results of the revolution could have been achieved even in a gradual reform process. Most of the results of the revolution, however, Tocqueville sees as prepared or enforced long before the events.

The centralization begun by the kings is only completed by the revolution. It leads to an increasing similarity in the way of life of citizens without equal political rights and results in a loss of civic spirit, which is promoted by the omnipresent administration. A political class that does not notice what it is doing because it is only administering and citizens who do not learn to work together because it is administered from above are counterparts to American reality. The reality of pre-revolutionary France includes, on the one hand, intellectuals who are at war with a political practice that is inaccessible to them, who are therefore building cloud cuckoo homes and dreaming of a utopian, complete equality. This also includes the old political class, the nobility, whose wealthy sections enjoy privileged rights that have long been given without corresponding local political tasks. Tocqueville shows how these undesirable developments lead to apolitical and anti-religious attitudes that arose over centuries of development. Where citizens are not used to working together - even if they are invited by the institutions - rejection and often hatred or contempt arise.

After the revolution, these pre-revolutionary mœurs , supported by the egalitarian order, come to the surface and shape the political life of France. In terms of hostility to Christianity, Tocqueville - who says he has lost his faith - sees the dangers of a lack of humility and threatening megalomania, which then culminates in the two Napoleonic adventures. (This should be described in the second volume of the work, which is no longer completed.) These adventures have become possible for him not least because of the lack of civic spirit in a society characterized by hatred and the absence of democratic mœurs .

The book about the Grande Révolution is full of hostile allusions to the rise of the "petit Napoléon" and his new politics. Not entirely without reproach, he describes that the French nobility - beyond the loss of their privileges - did not live up to their role model and leadership role - for Tocqueville one of the conditions for the coup d'état of Napoléon III.

The book is still having an impact today. High-ranking officials of the Chinese Communist Party publicly recommended his reading in 2013: Both Li Keqiang , the second man in the Communist Party, and Wang Qishan , the politburo member responsible for fighting corruption, want to make the so-called "Tocqueville Effect" known and known in China avoided through timely reforms.

Importance of the American and French Revolutions

Tocqueville recognizes the historical singularity of the American and French revolutions . He sees that the world has entered a new age that is primarily characterized by greater equality. Tocqueville understands this to mean the end of class privileges and an expansion of democratic rights. But while everyone is cheering for this development, Tocqueville, despite his agreement in principle, also points out the dangers of this progress. In particular, he recognizes that more equality and democracy do not necessarily have to mean more freedom. In a critical examination of a Montesquieu reception that was already dominant at the time , Tocqueville emphasizes: The essence of the democratic order is not democratic institutions, but liberal ways of thinking, behaving and speaking as well as a discourse steeped in these liberal customs (the mœurs ).

This realization forms the central core of Tocqueville's work: he devotes all his passion to the purpose of showing how human freedom can be maintained in the modern world. According to Tocqueville, freedom threatens in several ways. On the one hand, he sees it in the spreading individualism , which is particularly favored by an all-dominant motive for acquisition. This leads to the fact that the individual increasingly withdraws into his private life and is not involved in public affairs. This indifference on the part of the citizens favors a “benevolent despotism ”, which is characterized by an excessive central state and an incapacitating bureaucracy . In the end, there is a risk of a relapse into dictatorship or even into an order that is now called totalitarian .

According to Tocqueville, freedom can be saved through what is commonly referred to as civil society : through associations, freedom of the press , but above all through political participation , which in turn requires federal structures, in particular strong and autonomous or semi-autonomous municipalities, as well as the principle of subsidiarity . These are the “schools of freedom” that Tocqueville found in America and that he greatly admired. These institutions guarantee the mœurs mentioned above .

Tocqueville does not define the concept of freedom, which is central to his work. As a result, there are a number of interpretive approaches to Tocqueville today, some of which contradict each other. According to one view, Tocqueville ultimately understands freedom to be nothing other than human dignity . Another interpretation sees him as a very radical liberal who rejects all welfare state regulations and considers free initiative to be the center of liberal activity. Understood in this way, freedom for Alexis de Tocqueville is essentially freedom of action, be it that of the individual citizen, be it - and this is his main political accent - in cooperation with fellow citizens.

Press

Alexis de Tocqueville honors three major press functions:

- It guarantees freedom - it can expose political activity

- maintains the community and offers members common topics.

- enables rapid joint operations

The power of the press is to express different opinions and to allow the individual to become more firmly anchored in social consciousness.

Tocqueville also pointed out that newspapers in different countries differ in content and format, and these differences result more from cultural and political reasons than economic ones.

He also stressed that the evil the press produces is less than what protects the citizens. The inclination of the press could be increased by the creation of more newspapers.

Works

- 1831 Quinze jours au désert .

- German: In the North American wilderness. A travel description from 1831 Verlag Hans Huber Bern / Stuttgart 1953.

- translated by Heinz Jatho: Fifteen days in the wilderness . diaphanes, Zurich 2013, ISBN 978-3-03734-328-9 .

- 1833 Du système pénitentaire aux États-Unis et de son application en France (On the Penitentiary System in the United States and Its Application to France, German: America's reform system and its application to Europe) with Gustave de Beaumont

- 1835/1840 De la democratie en Amérique . 2 vols. Paris

- German: About democracy in America , Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1956 and more often

- 1835 Mémoire sur le paupérisme (German: The misery of poverty. About pauperism , Avinus Verlag, Berlin 2007. ISBN 978-3-930064-75-5 . Made on demand)

- 1835 L'Angleterre et l'Irlande. Le second voyage en Angleterre (German: trips to England and Ireland )

- 1836 The social and political order of France before and after 1789

- 1841 Travail sur l'Algérie (German: Thoughts on Algeria 2006 in the “Small Political Writings” published by Harald Blum, Akademie Verlag Berlin)

- 1856 L'ancien régime et la révolution . Paris (German: The old state and the revolution . German by Theodor Oelckers . 1867)

- 1893 memories with an introduction by CJ Burckhardt, Stuttgart, 1954ff. (Private records of experiencing the French Revolution with no intention of publication)

- New edition, translated by Dirk Forster, Karolinger Verlag, Vienna / Leipzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-85418-139-2

- Alexis de Tocqueville as a member of parliament, letters to his election agent Paul Clamorgan 1837–1851 (ed. J. Kühn) Hauswedell u. Co., Hamburg 1972, ISBN 3-7762-0006-5

- Small political writings published by Harald Bluhm, Berlin 2006, Akademie Verlag, ISBN 978-3-05-004175-9

- Œuvres I – III (édition publiée sous la direction de André Jardin) Paris 1991ff. ( Bibliothèque de la Pléiade )

- Œuvres complètes I – XVIII , Paris 1961ff. 30 volumes.

Tocqueville Effect

The Tocqueville effect is a phenomenon in sociology or social psychology . The point is that revolutions do not break out when the repression is sharpest, but when the regime has already softened and is ready for reforms, so dissatisfaction can express itself more risk-free, as in the case of the Ancien Régime under Ludwig, which Tocqueville analyzed XVI. , but also in the November Revolution in Germany after the reforms of Reich Chancellor Max von Baden or in the Eastern Bloc after the de-Stalinization by Nikita Khrushchev (1956) and 1989–1991 after the perestroika under Michail Gorbachev :

“The government that is destroyed by a revolution is almost always better than its immediate predecessor. Experience shows that the most dangerous moment for a bad government is usually when it begins to reform. "

Tocqueville Paradox

In sociology, the Tocqueville Paradox is the phenomenon "that as social injustices are reduced, sensitivity to remaining inequalities increases".

Others

In his honor, the Alexis de Tocqueville Society awards the Prix Alexis de Tocqueville every two years in France .

Tocqueville in literature

- Peter Carey : Parrot and Olivier in America (Parrot and Olivier in America, Ger.) Roman. Frankfurt a. M. 2010. ISBN 978-3-10-010234-8

literature

- Harald Bluhm / Skadi Krause (ed.): Alexis de Tocqueville - Analyst of Democracy . Fink, Paderborn 2016, ISBN 978-3-7705-5954-1 .

- Hugh Brogan: Alexis de Tocqueville. Prophet of Democracy in the Age of Revolution. Profile Books Ltd, London 2006, ISBN 1-86197-509-0 ( BBC Radio 4 discussion with the author , November 22, 2006).

- Arnaud Coutant: Tocqueville et la constitution democratique. Souveraineté du peuple et libertés. Essai. Mare et Martin, Paris 2008, ISBN 978-2-84934-058-5 ( Droit & science politique 2).

- Emil Dürr : Democracy in Switzerland according to Alexis de Tocqueville's view. In: Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde , Vol. 23, 1925, pp. 225–279. ( e-periodica.ch )

- Gerd Habermann : An Alexis de Tocqueville breviary. hep-Verlag AG, Bern 2005, ISBN 3-7225-0003-6 .

- Karlfriedrich Herb , Oliver Hidalgo: Alexis de Tocqueville. Campus, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 2005, ISBN 3-593-37647-4 ( campus introductions ).

- Michael Hereth : Alexis de Tocqueville. The threat to freedom in democracy. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [a. a.] 1979, ISBN 3-17-005396-5 .

- Michael Hereth : Tocqueville as an introduction. Junius, Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-88506-869-9 ( Introduction 69), (2nd improved edition, ibid 2001, ISBN 3-88506-333-6 ).

- Michael Hereth, Jutta Hoeffken (eds.): Alexis de Tocqueville. To politics in democracy. Symposium on the 175th birthday of Alexis de Tocqueville. From 27. to 29. June 1980 in the Theodor-Heuss-Akademie zu Gummersbach Baden-Baden 1981. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1981, ISBN 3-7890-0679-3 ( writings of the Friedrich-Naumann-Foundation. Scientific series ).

- André Jardin: Alexis de Tocqueville. Life and work. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 1991, ISBN 3-593-34434-3 .

- Lucien Jaume: Tocqueville Fayard, 2008, Paris 2008, ISBN 978-2-213-63592-7 .

- Skadi Siiri Krause: A new political science for a new world - Alexis de Tocqueville in the mirror of his time, Suhrkamp Taschenbuch, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-518-29827-5 .

- Skadi Siiri Krause (ed.): Experience spaces of democracy. On state thinking by Alexis de Tocqueville, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-515-11835-4 .

- Jacob P. Mayer: Alexis de Tocqueville. Analyst of the mass age. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1954, ISBN 3-406-02485-8 (3rd modified and expanded edition. Beck, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-406-02485-8 ( Beck'sche black series 85)).

- Claus Offe : Self-Contemplation from a Distance / Tocqueville, Weber and Adorno in the United States. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-518-58399-9 .

- Karl Pisa: Alexis de Tocqueville. Prophet of the mass age. A biography. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-421-06178-5 .

- Günter Rohrmoser : Conservatism in the 19th Century. Alexis de Tocqueville. In: Günter Rohrmoser: Conservative thinking in the context of modernity. Society for cultural studies, Bietigheim / Baden 2006, ISBN 3-930218-36-4 .

- Alan Ryan: Genius with flaws. About Alexis de Tocqueville. In: Mercury. German magazine for European thinking. 62, issue 3, March 2008, ISSN 0026-0096 , pp. 206-217.

- Otto Vossler: Tocqueville. (Lecture). Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1966 ( meeting reports of the Scientific Society at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt am Main 5, 1, ISSN 0512-1523 ).

- Sheldon S. Wolin : Tocqueville between Two Worlds. The Making of a Political and Theoretical Life. Princeton, NJ [et al. a.], 2003.

Web links

- Literature by and about Alexis de Tocqueville in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Alexis de Tocqueville in the German Digital Library

- Tocqueville Tour: Exploring Democracy in America 1997/1998 (C-SPAN School Bus on road trip)

- "Democracy in America" , the full text of both volumes

- Dominik Sommer, Market-Mediated Mass Art (Berliner Journal für Soziologie 15, Issue 1, 2005 - Article on the influence of Tocqueville's cultural sociology in the second America volume on Max Horkheimer's and Theodor W. Adorno's cultural industry thesis )

- Christine Alice Corcos: Alexis de Tocqueville - A Comprehensive Bibliography

- Short biography and list of works of the Académie française (French)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b http://www.gradesaver.com/classicnotes/authors/about_alexis_tocqueville.html

- ↑ http://www.tocqueville.org/chap1.htm#part1

- ↑ http://www.tocqueville.culture.fr/fr/portraits/p_alexis-enfance.html

- ↑ a b http://www.tocqueville.culture.fr/fr/portraits/p_alexis-metz.html

- ↑ Özkan Ezli, Boundaries of Culture: Autobiographies and Travel Descriptions between Occident and Orient, Konstanz 2012, p. 110.

- ↑ Alexis de Tocqueville, Arthur Goldhammer (translation): Democracy in America , page 907. ISBN 1-931082-54-5 , ( digitized English), accessed on January 22, 2011

- ^ Arnaud Coutant, Tocqueville et la constitution democratique , Mare et Martin, 2008, 680 p.

- ↑ A. d. Tocqueville, souvenirs . Préface de Claude Lefort, Paris: Gallimard 1999, p. 25. He also exclaimed: “Do not see that views and ideas are gradually spreading in the working class which not only shake individual laws but also the foundations of the social order itself today and fall over? ... I believe that at the moment we are sleeping on a volcano. ”(Quoted from A. de Tocqueville,“ About Democracy ”; Preliminary remark“ About this book ”; Fischer-Bücherei 138, Oct. 1956)

- ↑ [A. d. Tocqueville, souvenirs . Préface de Claude Lefort, Paris: Gallimard 1999, p. 217 f. - See Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison, Coloniser. Exterminers. Sur la guerre et l'État colonial , Paris: Fayard 2005, p. 318 f]

- ^ Pawel Zaleski: Tocqueville on Civilian Society. A Romantic Vision of the Dichotomic Structure of Social Reality . In: Felix Meiner Verlag (ed.): Archive for conceptual history . 50, 2008.

- ↑ Henning Ritter, Nahes und Fernes Unglück. Experiment about compassion , CH Beck, Munich 2004, p. 106.

- ↑ Quoted in Domenico Losurdo : Struggle for history. Historical revisionism and its myths , PapyRossa, Cologne 2007, p. 236 f.

- ^ Domingo Faustino Sarmiento: Barbarism and Civilization. The life of Facundo Quiroga . Translated into German and commented by Berthold Zilly, Eichborn: Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 11; ISBN 978-3-8218-4580-7 . - On the meaning of Tocqueville for Sarmiento cf. Susana Villavicencio: Sarmiento lector de Tocqueville , pp. 315-324; Diego Tatián: Sarmiento y Tocqueville. En busca del animal político , pp. 333–340, in: Marisa Muñoz, Patrice Vermeren (ed.): Repensando el siglo XIX desde América Latina y Francia: Homenaje al filósofo Arturo A. Roig , Ediciones Colihue SRL, Buenos Aires 2009.

- ^ Domenico Losurdo: Freedom as a privilege. A counter-history of liberalism , PapyRossa, Cologne 2010, p. 298.

- ↑ Tocqueville, Alexis de (1835): " De la démocratie en Amérique (PDF; 791 kB)" Volume 1, Part 2, pp. 90f.

- ^ So Bernd Hüttemann : European governance and German interests. Democracy, lobbyism and Art. 11 TEU, first conclusions from "EBD Exklusiv" , November 16, 2010 in Berlin. In: EU-in-BRIEF . No. 1, 2011, ISSN 2191-8252 , PDF ( Memento from April 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) p. 3.

- ↑ Seloua Luste Boulbina (PDF; 246 kB) 2008 on Tocqueville as a colonialist, p. 18 f. Luste Boulbina sees Tocqueville's political thinking as a whole being shaped by colonialism, based on his study of America as a colony emancipated from England over the French Antilles as old colonies in which slavery is to be abolished with appropriate compensation for the former slave owners, to Algeria as a new colony .

- ↑ Harald Bluhm in the introduction to Alexis de Tocqueville: Small political writings , Akademie Verlag: Berlin 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ See demography ( memento of July 30, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) - In 1846 he wrote to Francis Lieber in the USA and asked for documents on how the Americans managed to bring so many Christian Europeans into their country because “luring” Europeans to Algeria is not so easy (cf. Domenico Losurdo [2010], p. 298).

- ↑ Harald Bluhm in the introduction to Alexis de Tocqueville: Small political writings , Akademie Verlag: Berlin 2006, p. 32.

- ↑ Thoughts on Algeria , in: A. d. Tocqueville, Kleine Politische Schriften , ed. by Harald Bluhm, Akademie Verlag: Berlin 2006, pp. 109–162.

- ↑ This will be the case with Tocqueville's consent in the revolutionary year 1848, as Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison in “ Coloniser. Exterminers. Sur la guerre et l'État colonial ”, p. 308.

- ↑ For the colonized population this led to the establishment of a permanent state of emergency , which from 1875 was given its framework in the Code de l'indigénat .

- ↑ Seloua Luste Boulbina (2008), p. 17. - See also with all of Tocqueville's texts on Algeria: Alexis de Tocqueville: Sur l'Algérie . Presentation, notes, biography et bibliographie de Saloua Luste Boulbina, Garnier-Flammarion: Paris 2003; ISBN 2-08-071175-X .

- ↑ Mark Siemons: Is China facing a revolution? in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, No. 35, February 11, 2013, page 27

- ^ A b Eric Maigret: Socjologia komunikacji i mediów . Oficyna Naukowa, Warszawa 2012, p. 47 .

- ^ A b Eric Maigret: Socjologia komunikacji i mediów . Oficyna Naukowa, Warszawa 2012, p. 48 .

- ↑ quoted from JP Mayer: Alexis de Tocqueville, Analytiker des Massenzeiters , Munich 1972, p. 85.

- ^ Geißler, Rainer: Die Sozialstruktur Deutschlands, 4th updated edition, Wiesbaden 2006, p. 301.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Edouard Drouyn de Lhuys |

Foreign Minister of France June 2, 1849–31. October 1849 |

Alphonse de Rayneval |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tocqueville, Alexis de |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tocqueville, Charles Alexis Henri Maurice Clérel de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French publicist and politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 29, 1805 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Verneuil-sur-Seine ( Seine-et-Oise department ) |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 16, 1859 |

| Place of death | Cannes |