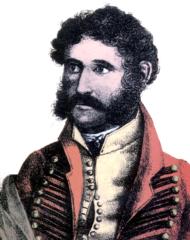

Juan Facundo Quiroga

Juan Facundo Quiroga (* 1788 in San Antonio , La Rioja province ; † February 16, 1835 ) was an Argentine caudillo who was initially a supporter of Bernardino Rivadavia , but who fought longest on the side of the federalists during the formation phase of the Argentine nation state .

Life

Facundo Quiroga was born in San Antonio, a town in the La Rioja province, into an estancia family. His father had served as a militia officer. Quiroga initially worked as a Peón , stayed in Buenos Aires during the May Revolution and was enlisted in the military. Despite evident leadership qualities, he was opposed to military discipline, so he deserted and withdrew to his western homeland. Between 1816 and 1818 he was a captain in a militia unit and fought for independence from the Spanish . In La Rioja he overthrew the two most influential families, acquired the reputation of a “ tiger of the plains ” (= “ Tigre de Los Llanos ”) among the population and became governor of La Rioja. He brought the provinces of Tucumán and San Juan under his rule after defeating Gregorio Aráoz de La Madrid's troops in 1826. Typically for the caudillismo , Facundo Quiroga combined his leadership of the militia with the supply of his landless clientele. This enabled him to own land and do business as a merchant, which enabled him to grant loans. He also sold weapons to the state and was able to mobilize 2,000 armed riders himself. In 1830 he was defeated in the battle of José María Paz and went back to Buenos Aires, where he joined the dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas and won a victory against La Madrid at the head of the federalist troops. In 1835 he was supposed to mediate a conflict between two provinces for Rosas and was shot in a robbery on his carriage on the way back near Córdoba (Argentina) . Since Rosas saw him as a rival, the rumor, which had never been resolved, started circulating that Rosas had been the commissioner of the murder.

Depiction of Facundo Quirogas by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento

In the book “ Barbarism and Civilization ” published in exile in Chile in 1845 . For the author Domingo Faustino Sarmiento , the life of Facundo Quiroga is a representative of barbarism , whom he sees as a gaucho roaming the uncivilized “desert” beyond the Europeanized and civilized cities, who “ destroys and humiliates all known civilized means ”, “ one impulsive, unrestrained, unscrupulous greed "and wants to gain control over the cities," barbaric, arbitrary, American ", in the" spirit of the Arab , Tatar drover troops ".

“He felt strong and willing to act; he was driven by a blind, indefinite instinct to which he obeyed; he was the country commander, the 'gaucho malo' (= 'evil gaucho'), an enemy of the ordinary judiciary, the civil order, the decent man, the scholar, the tailcoat, in one word: an enemy of the city. "

Nevertheless, Sarmiento cannot deny him his respect. Because " power educates, and Quiroga had all the high spiritual gifts that allow a person to always do justice to a new position, however prominent it may be ". In his eyes, Rosas is worse: “ barbaric like Asia, despotic and bloodthirsty like Turkey, persecuting and despising the intelligentsia like Islam ”, which he also used for the “ instigator of the murderers ” Facundo Quirogas because of his more refined and secret police methods to point to with the finger.

Historical classification

Sarmiento already notes that ten years after Facundo Quiroga's death the myth arose that he was still alive or would come back. Michael Riekenberg builds on this and emphasizes that the role of the caudillo, to be loved and feared, included not only giving his militia militia shares of booty, feeding and clothe them, but also demonstrating familial affability in his area of life . This happened at weddings, baptisms and religious festivals, so that Facundo Quiroga also appeared as the guardian of traditions and acquired a mystically glorified reputation among the rural population.

“Caudillos like Quiroga (...) brought landless people, day laborers, former slaves, tenants and in some cases indigenous people into politics in the early 19th century, thereby creating a counterweight to the urban, liberal elites who viewed politics as business and to whom the rural population appeared rather strange and suspicious than 'barbarians'. "

Riekenberg emphasizes that nothing special or shrouded in mystery can be seen in the caudillism that becomes visible in Facundo Quiroga , as history has long believed. It is only a local variant of “ a form of political power that has its own resources, is person-centered and extends into the structures of the state ”.

Afterlife

As is the case with all political or military leaders in the formation of the Argentine state - above all with Julio Argentino Roca , but also with Juan Manuel de Rosas or Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, who later became president - they were named patrons of the public by the 20th century at the latest Facilities, monuments or streets have been instrumentalized, as is Facundo Quiroga, most noticeably in the province of Rioja with the Department General Juan Facundo Quiroga .

literature

- Michael Riekenberg: Small History of Argentina. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-58516-6 .

- Domingo Faustino Sarmiento: Barbarism and Civilization. The life of Facundo Quiroga. transfer u. commented by Berthold Zilly. Eichborn, Frankfurt a. M. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8218-4580-7 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Juan Facundo Quiroga in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ See biography (Spanish) .

- ↑ Michael Riekenberg : Small History of Argentina , CH Beck: Munich 2009, p. 82.

- ^ Name and subject index in DF Sarmiento, Barbarei und Zivilisation. The life of Facundo Quiroga , rendered & commented by Berthold Zilly, Eichborn: Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 377 f.

- ↑ barbarism and Civilization, pp. 37-40.

- ↑ barbarism and Civilization, p. 121.

- ↑ barbarism and Civilization, p. 143; 148.

- ↑ barbarism and Civilization, p. 155.

- ↑ barbarism and Civilization, p. 242.

- ↑ barbarism and Civilization, p. 296.

- ↑ barbarism and Civilization, p. 256.

- ↑ barbarism and Civilization, p. 9.

- ↑ Michael Riekenberg (2009), p. 84.

- ↑ Michael Riekenberg (2009), p. 85.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Quiroga, Juan Facundo |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Quiroga, Facundo |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Argentine caudillo |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1788 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | San Antonio , La Rioja Province |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 16, 1835 |