Rip Van Winkle

Rip Van Winkle is a short story by the American writer Washington Irving (1783-1859) that first appeared in 1819 as part of his Sketch Book . In addition to The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (dt. The legend of the Sleepy Hollow ) from the same band it is considered as the first short story of American literature and is still one of the best known. Based on a German legend , it tells the story of the farmer Rip Van Winkle, who fell into a magical sleep in the mountains of New York during the English colonial era, only wakes up after twenty years and realizes that he is no longer a subject of the English king, but rather Is a citizen of the United States.

content

The beginning of the story takes place in the English colonial times of today's American state New York . In an idyllic village of Dutch settlers between the Hudson River and the “ Kaatskill ” mountains, the farmer Rip Van Winkle lives a peaceful life and, as a simple and good-natured man, is equally popular with women, children and dogs. But since he has an "insurmountable aversion to all kinds of considerable work", he often has to endure the wrath of his disgruntled wife (only called "Dame Van Winkle") and uses every opportunity to escape the inconveniences of married life and domesticity Accompanying your dog to roam the woods to fish or hunt. On one of these forays through the Kaatskills, in the middle of the forest, he suddenly hears his name and sees a human figure, dressed in old-fashioned Dutch costume and carrying a barrel of schnapps on his shoulder. Without a word he follows the apparition through a ravine to a depression where, to his great astonishment, a whole company of similarly strange figures - the scene reminds Rip of an old Flemish painting - has come together to play skittles. Not a word is exchanged, only the rumble of the balls disturbs the silence. Without a word, Rip is told to pour the players out of the barrel, from which he finally tastes himself, before falling into a deep sleep.

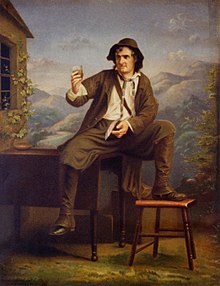

painting by John Quidor , 1849. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

When he wakes up, the ghostly company is gone, as is his dog; Instead of his rifle, Rip finds only a rotten shotgun, and to his surprise he finds that his beard has apparently grown a foot overnight. When he returns to his village, he hardly recognizes it - new houses have been built everywhere, his own house is dilapidated and abandoned, and all residents (and dogs) seem unknown to him and treat him with suspicion. Rip's beloved pub has given way to the Union Hotel , and it seems to him that the familiar portrait of the English king still hangs there, but it now bears the words General Washington . Before that there is a speaker about "elections", "citizens", the "Congress", the "Heroes of '76" and similar things that Rip cannot understand at all. When confronted by the curious crowd, the distressed Rip declares that he is a “poor, calm man, a resident of the village and a loyal subject to the king, God bless him!” And is then accused of being a traitor and be a spy.

Only when an old woman recognizes him does the riddle solve itself: Rip slept not one night, but twenty years. In the meantime, his wife has passed away (the only comforting news for him), his children have grown up, and most of all, he slept through the American Revolution and the War of Independence. The oldest villager explains that the wonderful characters Rip once met in the forest must have been none other than Henry Hudson and his Dutch crew; every twenty years Hudson paused in the mountains to see the progress of the valley named after him. Meanwhile, Rip Van Winkle finds a place in his daughter's household and, freed from the “yoke of marriage”, spends a pleasant retirement. He tells his story to all children and travelers so often that it is finally known across the country, and although, according to the narrator, some angry voices claim that he was out of his mind, at least the Dutch settlers never doubted her Truth.

Work context

Emergence

Rip Van Winkle is the "part sketchbook " (The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.) , The Irving 1818/19 written in England. In 1815 he had come to Liverpool to help his brother manage the English branch of the Irving family business, but he was unable to avert the decline and eventual bankruptcy of the company in 1818. After these sobering years, Irving found himself on his own in a foreign country, fell into depression and finally made the decision to make literature his profession. According to a family anecdote , Rip Van Winkle was written in June 1818 when Irving was staying with his sister Sarah Van Wart in Birmingham . One evening he and his brother-in-law, Henry Van Wart, indulged in memories of happy youth days in the rural idyll of the Hudson Valley. Suddenly he jumped up, went to his room and wrote until dawn, and then, holding the manuscript in his hands, appeared cheerfully at the breakfast table and read the story to his hosts.

The texts of the sketchbook first appeared in America over a period of around one and a half years in seven individual issues, and in book form for the first time in 1820 in two volumes in England. Rip van Winkle was published as the fourth and final “sketch” of the first American issue (the fifth, if you add the author's introduction) from May 1819. It was the first whose location is not Europe, but Irving's homeland New York. Rip Van Winkle can thus be read as a tribute to his New York audience. An autobiographical connection is suggested by the fact that the protagonists of the two previous sketches, The Wife and Roscoe , as well as Rip Van Winkle, are threatened with financial ruin and impoverishment - in the case of Rip Van Winkle, it is obvious that this is ultimately not just this one Emergency escapes, but at the end of the story is also known and honored as a storyteller.

Narrative instances

The story is embedded in a complex publisher's fiction: until his biography of Columbus in 1828, Irving always published under different pseudonyms , even if his authorship was known. The narrator and alleged author of the sketchbook is a certain Geoffrey Crayon, an American gent. ( Gentleman ) traveling in Europe. The Rip Van Winkle , on the other hand, is presented as a work from the estate of the historian Diedrich Knickerbocker , which was incorporated into Crayon's sketches . Irving had already put forward this persona in 1807 as the narrator of his satirical History of New York (English: History of New York from the beginning of the world to the end of the Dutch dynasty ): According to this, Knickerbocker disappeared without a trace one day and his landlord had it in his estate The found papers were published in order to pay Knickerbocker's outstanding debts with the proceeds. In the sketchbook , Rip Van Winkle appears framed by a preface, an appendix and a postscript by the narrator Geoffrey Crayon - a parody of the kind of critical apparatus that Walter Scott or the Brothers Grimm added to their collections of songs and fairy tales. Crayon vouches for the reliability of his informant Knickerbocker:

|

|

The truthfulness of the story is underlined again in the postscript, in which an accompanying remark by Knickerbocker is quoted. Knickerbocker claimed in it that he not only met Rip Van Winkle personally, but “even saw a credentials on the subject”, “which was recorded by a village judge and signed with a cross in the judge's own handwriting. So the story is beyond any possible doubt. ”So the story is conveyed and ironically broken by three narrators - Geoffrey Crayon, Diedrich Knickerbocker, Rip Van Winkle.

genus

Particularly important Rip Van Winkle for the genre theory : Despite the fact that there was fictional short stories before Irving and a definition of the nature of the short story ( short story ) - a distinction about the story , the fairy tale or the amendment - in literary studies to is openly discussed today, Irving, with Rip Van Winkle as “Urtext”, is generally considered to be the “inventor” of the short story, a genre that, unlike in German or English, has achieved great popularity, especially in American literature. While the other sketches in the sketchbook are hardly narrative and mostly not fictional either and are more closely related to the essay or travel literature , Rip Van Winkle depicts a self-contained plot that is structured around a concise and extraordinary "central event" or basic motif . This also applies to the “sketches” The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (“The Sage of the Sleepy Gorge”) and the now hardly read play The Specter Bridegroom (“The Ghost Groom”), which appeared in later issues of the Sketch Book . The designation as a short story was made retrospectively; Irving himself referred to his short prose pieces as sketches & short tales .

swell

In an afterword to the story, Irving suggests via his narrator that the Kyffhauser legend of the sleeping Friedrich Barbarossa was a model for him when he wrote the Rip Van Winkle . Soon after the appearance of the Sketch Book , however, allegations were made against Irving that he had failed to reveal his true sources and was guilty of plagiarism, so that he was called to a defense in Bracebridge Hall (1824). In fact, it is now considered certain that the direct model for the Rip Van Winkle is the legend of the goatherd Peter Klaus, also from Kyffhäuser, which Johann Karl Christoph Nachtigal published under the pseudonym Otmar for the first time in 1800 in his collection of Volcks sagas from the Harz Mountains. Irving probably got to know this legend through Büsching's folk sagas, fairy tales and legends (1812). The fact that Irving mixed up the two sagas may be due to the fact that they are combined in one chapter in Büsching's collection (“Legends and Fairy Tales of the Harz”) and are also thematically related. Some passages of Irving's story are actually little more than translations of Otmar's original, so that for example Stanley T. Williams in his Irving biography (1935) renewed the complaint that Irving had "stolen". In fact, Rip Van Winkle is not only four times the size of its role model, but also contains significant changes and additions, in particular the relocation of the setting to New York and the embedding of the plot in a specific historical context.

The central motif of the magic sleep can be found in numerous legends and fairy tales from a wide variety of cultures. In the Aarne-Thompson-Index , the classification of fairy tale materials that is decisive for narrative research , the motif of magic sleep is listed under the code AaTh 766 (" dormouse "). The widespread use of the motif has meant that other information about Irving's alleged sources can often be found in the literature. When the Dutch historian Tiemen De Vries got excited in a series of lectures in 1912 about Irving's portrayal of the Dutch as lazy and simple, he also falsely claimed that Irving had used Van Winkle for the Rip from Erasmus of Rotterdam - Erasmus had the in one of his writings ancient Greek legend carried out by Epimenides , who is said to have slept in the Dictaean cave for 57 years . Another more likely direct source is the Scottish saga of Thomas the Rhymer , in which the mortal Thomas is invited by the Queen of the Elves to a festival and when it ends finds that seven years have passed since then. This legend - still well known today in the form of a ballad - Irving mentioned in a letter to his brother Peter, which he wrote in 1817 after his visit to Walter Scott .

The related motif of the Rapture of the Mountains , as found in the Kyffhauser saga of the enchanted Friedrich Barbarossa, is echoed in Rip Van Winkle : Just as Barbarossa's sleep is linked to the hope of the renewal of imperial glory, Henry Hudson, who has grown too mythical, wakes up on the development of New York. As in the German legend over the Kyffhäuser, ravens also fly over Irving's Kaatskill Mountains, and Rip Van Winkle's beard grows to an astonishing length during his magical sleep. Irving knew the motif of the mountain rapture not only in connection with the Kyffhauser saga. In his notebook he recorded his impressions of reading the letters of a French traveler about Germany from Johann Kaspar Riesbeck in 1818 and noted in particular passages from the 14th letter about Salzburg and the surrounding area, including the reference to a legend after which Karl der Große with his army in the Watzmann waiting for his resurrection, as well as a note about “magicians whose white beards have grown ten or twenty times around the table on which they sleep, and millennial hermits who led the chamois hunters through underground passages and full of fairy tale palaces Gold and precious stones have shown ”. Other classic legend motifs can also be found in Rip Van Winkle : Rip's return is reminiscent of Odysseus' return to Ithaca : While the hero of the Odyssey is only recognized by his dog Argos , on his return Rip himself is growled at by his once loyal dog Wolf .

Themes and motifs

Romantic

As explained above, the motif of the magical sleep is borrowed from a German fairy tale through Nachtigal's mediation and reflects Irving's preoccupation with the literature of German Romanticism , which was received intensively in England and the USA during these years. While Irving's early works such as the Satires in Salmagundi and the History of New York were trained by English neoclassicalists such as Joseph Addison or Oliver Goldsmith , the Sketch Book marks his turn to a romantic way of thinking. After his arrival in Europe in 1815, his friendship with Sir Walter Scott made a great impression on him, and around 1818 - like Scott a few years before him - he began to learn German and dealt with legends and fairy tales. The "folk" subject of Rip van Winkle shows the effect of this reading: unlike his previous works, the story is not set in the city, but in a rural idyll decorated with numerous picturesque details :

|

|

The Kaatskill mountains are not only transfigured into a place of longing for romantic wanderlust due to the beauty of nature , but also provided with legends pointing to the past. Like numerous American writers before and after him, Irving complained that the New World did not offer a time-honored story that could be edited through literary means. In order not to have to do without the romantic, nostalgic enthusiasm for bygone worlds in his homeland, Irving now - following on from his History of New York - wrote a corresponding folklore to the settlers of the Dutch colonial era ; to a lesser extent, he also weaves alleged Indian myths about the Kaatskills into the story. In 1843 he wrote: "When I first wrote about the legend of Rip Van Winkle, I had been thinking for some time to add a little color and tradition to some interesting places in the landscape of our nation". The result of this romantic escape from the world is a place in which “the strange and unexpected, the mysterious and the supernatural are not only conceivable, but actually happen before the eyes of the reader”. This place, however, has little in common with the disgraceful social reality in the age of industrialization, which led William Hazlitt to claim as early as 1825 that Irving's writings were “literary anachronisms”.

Political

Irving achieves the “Americanization” of the mythical material on the one hand by localizing it in New York, but on the other hand also by embedding it in a specific historical context. Rip oversleeps the American Revolution and is suddenly thrown from the time of the monarchy into the turmoil of the young republic. This break is symbolically indicated at Rips Awakening: Instead of the ravens that previously flew over the mountains - a clear borrowing from the Kyffhauser legend - an eagle, the heraldic animal of the United States, now circles over the Kaatskills. Irving's description of Rip's return reveals a very ambivalent attitude towards the legacy of the revolution:

|

|

The cozy gatherings under the shady tree of the village tavern have given way to excited political debates, a “skinny, gall-addicted-looking guy” gives a political speech, and the angry crowd asks Rip “whether he is a federalist or a democrat” and is later suspected to be a Tory, a loyalist loyal to the king and thus a traitor and spy.

Irving shows the deep rifts that the party system of democracy has torn between the inhabitants of the once harmonious village community. Irving hardly ever took a political position, but his description of Election Day in Rip Van Winkle clearly shows the distrust with which he faced egalitarian-democratic aspirations that gained the upper hand over the Federalist Party after the 1800s with Thomas Jefferson's presidency . The story has often been read as a parable in which Irving's delicate, intellectual alienation from American society, which is increasingly determined by rationalism and the pursuit of profit, is expressed.

In addition to the political conflict, the story also reflects the regional conflict between New Yorkers and New Englanders, who now had to come to terms with one another in a state with the constitution of the United States of 1787 . The "Union Hotel", which is now on the site of the former village tavern, is run by a Jonathan Doolittle, for example - a stereotypical name for a Yankee , i.e. a New Englander with all the attributes attributed to him, in the eyes of Irving like many other New Yorkers Before and after him, writers were particularly addicted to profit and hard-heartedness. It is evidently described as a “large, crooked, wooden building”, “with large, wide windows, some of which were broken and clogged with old hats and petticoats”. Even the guilt for Dame Van Winkle's death is blamed on a Yankee: "She burst a blood vessel in a fit of anger at a peddler from New England".

Personal

Since Irving's short stories, alongside James Fenimore Cooper's novels, mark the beginning of an independent American literature, they have also received some attention in the classic texts of American studies , which tried to draw conclusions about the “national character” from specifics of American literature. Lewis Mumford saw the story's immense popularity as being based on the fact that Rip offered a down-to-earth, if not disillusioned, alternative to the equally popular stories of Frontier heroes like Paul Bunyan : Precisely because Rip is lazy, useless and unable to develop, he reflected reflect the experience of an entire generation for whom hopes for adventure and fortune had proven illusory. Similarly, Constance Rourke attributed the subsequent success of Rip Van Winkle as a stage play in the post-American Civil War (the Gilded Age ) to the fact that it dramatized the key collective experience of this time with its portrayal of sudden change and a lost world.

So Rip's Los is only superficially happy - the story has often been read as the portrayal of a frightening loss of identity, which culminates in the scene of Rip's return to the village, because he "found himself so alone in the world" :

|

|

Even after the mystery of his identity has been solved, he spends a peaceful retirement, but is at the same time a living anachronism . He did not experience the “best man's age”, and so even as an old man he basically remains a child, so pays (according to the literary scholar Donald A. Rings) a “terrible price”. In the village community he only has the outsider role of a harmless, not really serious, if lovable old eccentric. That Rip's story is above all terrible, suggests a reading that sees in his name an allusion to the epitaph Rest in Peace (" rest in peace "). In fact, a certain morbid fascination with death permeates the entire “sketchbook” from the start.

Illustration by NC Wyeth , 1921

More recently, numerous critics have voiced their opinions on the pronounced misogyny that is evident in history. Such was Leslie Fiedler in Rip Van Winkle created the basic motive that his influential book Love and Death in the American Novel (1957) According characterizes the entire American literary history: the flight of the male protagonists of responsibility, growing up, marriage, and consequently the entire Civilization. The escapist fantasy of escaping into the wilderness, as portrayed in Cooper's leather stocking novels, is not yet fully developed since Irving finally allows Rip to return to his village, but the misogynistic component of this presumed American myth is already there: by depicting Rip as a refugee from the tyranny of women, he creates a "comical reversal of the [European] legend of the besieged maiden - a corresponding male fantasy of persecution". Fiedler's interpretation has since been taken up especially in feminist literary theory. Judith Fetterley , for example, opened her book The Resisting Reader (1978), an early work of feminist canon criticism , with a review by Rip Van Winkle . Fetterley sees Dame Van Winkle as a scapegoat , enemy, as " the other marked" even as the embodiment of restrictions, brings with it the "civilization" - she sees in it even the sadistic Big Nurse from Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest prefigured . Fetterley concludes that even from this first American short story the female reader is excluded, Dame Van Winkle remains nameless, little more than a caricature that certainly does not encourage identification . It is precisely her actually praiseworthy qualities - that she, abandoned by her useless husband, keeps the court in order and raises the children - is blamed on her as an effeminate lust for power; all sympathies are directed to the incompetent and lazy male protagonist without justification.

Reception and adaptations

The sketch book was popular in England and America, but - in addition to the Christmas sketches - Rip van Winkle in particular was often published as a single print, often included in anthologies , also distributed as a children's book and soon canonised as school reading. Like few other literary figures, Rip Van Winkle finally entered American folklore and was often referenced and parodied in high and popular culture. In addition to The Legend of Sleepy Hollow , it is also the only work from Irving's extensive oeuvre that is still known to a wide audience today. Shortly after Irving's death, William Cullen Bryant wrote in 1860 that the two stories are probably known to almost everyone in the United States who can read.

The residents of the Kaatskills knew how to market the high level of awareness of the story early on: As early as 1828, an inn advertised there with the claim to be "Rip van Winkle's Shanty", that is, to stand in the very spot where Rip fell asleep; around 1860 you could buy refreshing drinks from a showman disguised as a Rip, and around 1870 a hotel was built on the site, the Rip Van Winkle House . New York State Route 23 through the Catskills, inaugurated in 1924, is nicknamed the Rip Van Winkle Trail ; it crosses the Hudson River via a cantilever bridge built in 1935, the Rip Van Winkle Bridge .

Theater, opera, cinema and television

The theater played a special role in popularizing the subject in the USA. By 1866, Rip Van Winkle had already been brought to the stage in at least four adaptations. In 1866, a version adapted by Dion Boucicault was premiered in London, which with the actor Joseph Jefferson in the lead role was to become one of the most successful plays of the 19th century. Boucicault added another plot to the story, in which Rip has to fight off an opponent - his malicious son-in-law. The piece lived on 170 evenings in London before Jefferson brought it to New York in 1866. For the next 15 years Jefferson and his company went on extensive tours through the cities of the American hinterland, becoming known to a mass audience and ultimately becoming the most famous American actor of his time. Jefferson tried his hand at other roles again from 1880 onwards, but the audience identified him so much with his role that he played the Rip Van Winkle hundreds of times until the end of his life. The fact that the play's popularity was also, if not primarily, due to Jefferson's performance shows that it quickly disappeared from the repertoire after his death in 1905.

Jefferson's performance recorded William KL Dickson in several short silent films from 1896 on by his American Mutoscope and Biograph Company ; In 1903 the eight scenes were combined into a whole. Dickson's Rip Van Winkle was rated particularly worth preserving by the Library of Congress in 1995 and entered into the National Film Registry . A number of other film adaptations were made in the silent film era. When Walt Disney made the decision to produce a full-length cartoon around 1935, he initially had a film adaptation of Rip Van Winkle in mind. However, since he did not succeed in acquiring the film rights for the material from Paramount , he looked for another subject, so that instead of Rip Van Winkle, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs went down in film history as the first animation in feature film format. Since then, however, the character of Rip Van Winkle has appeared in various cartoon series, for example he met Popeye in 1941 , and in 1965 both Mr. Magoo and Fred Feuerstein slipped into his role. The German movie Good Bye, Lenin from 2003 takes up the motif of waking up in a changed form of society.

In 1884 Robert Planquette adapted the material for the operetta Rip , the story of the Italian-British composer Franco Leoni (1897) and the American Reginald De Koven (1920) brought to the stage as an opera.

literature

Among the lyrical adaptations and adaptations of the story are Edmund C. Stedman's Rip Van Winkle and His Wonderful Nap , Oliver Wendell Holmes ' Rip Van Winkle (1870) and Herman Melville's Rip Van Winkle's Lilac (undated, first published posthumously in Weeds and Wildings , 1924 ) to call. A section of Hart Cranes The Bridge (1930), one of the great poems of American modernism, is also titled Rip Van Winkle - the poet calls Rip Van Winkle the "Muse of Memory" and "Guardian Angel on a Journey into the Past" . Allusions to motifs from the narrative can also be found in works as diverse as James Joyce's Ulysses , Willa Cathers My Antonia and Dylan Thomas ' Alterwise By Owl-Light . Authors of postmodern literature have used Rip Van Winkle as a cipher for the rapid changes in the world in recent decades, for example Robert Coover in his one-act play Rip Awake (1972); Thomas Pynchon's novel Vineland (1989) also begins with a paraphrase by Rip Van Winkle : the awakening of an old hippie in California in 1984, who then finds out that his local pub has been converted into a yuppie designer bar.

In the 1820s, the Sketch Book was translated into several European languages and the story of Rip Van Winkle was also known internationally. The first German translation appeared in Leipzig as early as 1819 and is marked by the censorship passed that year with the Carlsbad resolutions . The anonymous translator changed the story, in some cases considerably, and in particular underlined Irving's presentation of the unpleasant aspects of a republican social order as opposed to the intimate harmony in the monarchy. The translation by Irving's “official” translator Samuel Heinrich Spiker first appeared in 1823 in the Berlin Pocket Calendar . Irving exercised considerable influence on German writers in the 19th century; explicit borrowings from Rip Van Winkle can be found in Wilhelm Hauff's Fantasies in the Bremer Ratskeller (1827), Wilhelm Raabe's Abu Telfan (1868) and in Ferdinand Freiligrath's Im Teutoburger Walde (1869).

In the 20th century, the treatment of the material by the Swiss writer Max Frisch in the radio play Rip Van Winkle (1953) and the resulting novel Stiller (1954) should be emphasized: The protagonist of the novel tells his defender the "fairy tale of Rip van Winkle", that he believes he read "decades ago [...] in a book by Sven Hedin ". For Frisch's novel, the theme of separation and return and how returnees deal with their ascribed identity is of central importance. The Rip van Winkle subject is updated in the 2007 (German 2008) novel Exit Ghost by Philip Roth . The protagonist Nathan Zuckerman returns to New York after eleven years from the loneliness of the Berkshires in New England (which are only 50 km from the Catskill Mountains ). Zuckerman will see George W. Bush re-elected in 2004 .

expenditure

- Rip Van Winkle . German by Ilse Leisi-Gugler. In: Fritz Güttinger (ed.): American narrators: short stories by Washington Irving, William Austin, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Edward Everett Hale, Ambrose Bierce and Henry James . Artemis-Verlag, Zurich 1946.

E-texts

- Rip Van Winkle - Digitized from an edition by David McKay Co, Philadelphia 1921. With color illustrations by NC Wyeth . ( Internet Archive )

- Washington Irving: Gottfried Crayon's sketchbook in the Gutenberg-DE project

Secondary literature

- Jean Beranger: Analyzes structurales de 'Rip Van Winkle.' In: Revue Française d'Etudes Américaines 5, 1978. pp. 33-45.

- Steven Blakemore: Family Resemblances: The Texts and Contexts of 'Rip Van Winkle.' In: Early American Literature 35, 2000. pp. 187-212.

- William P. Dawson: “Rip Van Winkle” as Bawdy Satire: The Rascal and the Revolution . In: ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance 27: 4, 1981, pp. 198-206.

- Howard Horwitz: Rip Van Winkle and Legendary National Memory. In: Western Humanities Review 58: 2, 2004.

- Klaus Lubbers: Washington Irving · Rip Van Winkle . In: Karl Heinz Göller et. al. (Ed.): The American Short Story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02212-3 , pp. 25-35.

- Terence Martin: Rip, Ichabod, and the American Imagination . In: American Literature 31: 2, May 1969, pp. 137-149.

- Colin D. Pearce: Changing Regimes: The Case of Rip Van Winkle. In: Clio 22, 1992. pp. 115-28.

- Henry A. Pochmann : Irving's German Sources in The Sketch Book . In: Studies in Philology 27, 1930, pp. 477-507.

- Donald A. Rings: New York and New England: Irving's Criticism of American Society . In: American Literature 38: 4, 1967, pp. 455-67.

- Jeffrey Rubin-Dorsky: Washington Irving: Sketches of Anxiety . In: American Literature 58: 4, 1986, pp. 499-522.

- Jeffrey Rubin-Dorsky: The Value of Storytelling: “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” in the Context of “The Sketch Book” . In: Modern Philology 82: 4, 1985, pp. 393-406.

- Walter Shear: Time in 'Rip Van Winkle' and 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.' . In: Midwest Quarterly 17, 1976. pp. 158-72.

- Michael Warner: Irving's Posterity. In: English Literary History 67, 2000. pp. 773-799.

- Sarah Wyman: Washington Irving's Rip Van Winkle: A Dangerous Critique of a New Nation . In: ANQ 23: 4, 2010, pp. 216-22.

- Philip Young: Fallen from Time: The Mythic Rip Van Winkle . In: Kenyon Review 22, 1960, pp. 547-573.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Stanley T. Williams, The Life of Washington Irving , Oxford University Press, New York 1935, Vol. 1, pp. 168-169.

- ^ Mary Weatherspoon Bowden: Washington Irving. Twayne, Boston 1981, p. 59; Andrew Burstein: The Original Knickerbocker: The Life of Washington Irving. Basic Books, New York 2006, p. 149.

- ↑ Ruth B. Bottigheimer: Washington Irving. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales . Volume 7, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1977, p. 295.

- ^ Washington Irving: Gottfried Crayon's sketchbook in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ↑ So z. B. Fred L. Pattee: Development of the American Short Story: An Historical Survey. Harper & Brother, New York 1923, pp. 1ff.

- ↑ Werner Hoffmeister: The German Novelle and the American "Tale": Approaches to a genre-typological comparison. In: The German Quarterly 63: 1, 1990, pp. 44-45.

- ↑ George S. Hellman (Ed.): Letters of Washington Irving to Henry Brevoort, together with other Unpublished Brevoort Papers. GP Putnam's Sons, New York 1918, p. 399: “I have preferred adopting a mode of sketches & short tales rather than long work, because I chose to take a mode of writing peculiar to myself; rather than fall into the mode or school of any other writer; and there is a constant activity of thought and a nicety of execution required in writings of the kind, more than the world appears to imagine ... ".

- ↑ Irving writes in a footnote to the sketch The Historian (1824): “I find that the tale of Rip Van Winkle, given in the Sketch Book, has been discovered by divers writers in magazines, to have been founded on a little German tradition , and the matter has been revealed to the world as if it were a foul instance of plagiarism marvelously brought to light. In a note which follows that tale I had alluded to the superstition on which it was founded, and I thought a mere allusion was sufficient, as the tradition was so notorious as to be inserted in almost every collection of German legends “. Quoted from Carey, Lea & Blanchard, Philadelphia 1835 edition, Volume II, p. 149.

- ↑ JCC Nachtigal: The goatherd at Zeno.org .

- ^ EL Brooks, A Note on the Source of 'Rip Van Winkle' , in: American Literature 25, 1954, pp. 495-496.

- ^ Walter A. Reichart, Washington Irving and Germany , University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1957, p. 28.

- ^ Williams, p. 183.

- ^ Pierre M. Irving, Life and Letters of Washington Irving , Volume 1, GP Putnam, New York 1862, p. 282.

- ^ Reichart, p. 23.

- ↑ On these and other myths see Young 1963.

- ↑ Pochmann, pp. 480-481.

- ↑ Pattee 1923, pp. 10-12.

- ^ Martin Scofield, The Cambridge Introduction to the American Short Story , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, p. 12.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 138-140

- ↑ Irving writes about his persona Diedrich Knickerbocker: “His historical researches, however, did not lie so much among books as among men; for the former are lamentably scanty on his favorite topics; whereas he found the old burghers, and still more their wives, rich in that legendary lore, so invaluable to true history ”.

- ↑ “When I first wrote the Legend of Rip Van Winkle my thoughts had been for some time turned towards giving a color of romance and tradition to interesting points of our national scenery, which is so generally deficient in our country”. Quoted in: Wagenknecht 1962, p. 174.

- ↑ James F. Tuttleton, Style and Fame: The Sketck Book , in: James F. Tuttleton (ed.), Washington Irving: The Critical Reaction , AMS Press, New York 1993, p. 53.

- ^ William Hazlitt, The Spirit of the Age , Henry Colburn, London 1825, p. 421.

- ↑ a b Martin, p. 142.

- ↑ a b Michael T. Gilmore, The Literature of the Revolutionary and Early National Period , in: Sacvan Bercovitch (Ed.), The Cambridge History of American Literature , Volume 1: 1590-1820 , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1997, pp. 669-671.

- ↑ On the political implications cf. general rings, 1967.

- ↑ Lewis Mumford, The Golden Day , Horace Loveright, New York 1926, pp. 68-71.

- ↑ Constance Rourke, American Humor: A Study of the National Character , Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York 1931, Chapter VII ( digitized ).

- ↑ August J. Nigro, The Diagonal Line: Separation and Reparation in American Literature , Susquehanna University Press, London and Toronto 1984, pp. 85-86.

- ^ Rings, p. 455.

- ↑ George Wetzel, Irving's Rip Van Winkle , in: Explicator 10, 1954.

- ^ Leslie Fiedler, Love and Death in the American Novel , Criterion, New York 1960, p. 6.

- ^ Judith Fetterley: The Resisting Reader: A Feminist Approach to American Fiction. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1978, pp. 2-10.

- ^ William Cullen Bryant: Discourse on the Life, Character and Genius of Washington Irving. In: George P. Putnam (ed.): Washington Irving . GP Putnams, New York 1860. p. 22.

- Jump up ↑ Irvin Richman, The Catskills: In Vintage Postcards , Arcadia Publishing, Richmond SC 1999, p. 41.

- ↑ David Stradling, Making Mountains: New York City and the Catskills , University of Washington Press, Seattle and London 2007, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Stephen Johnson, Joseph Jefferson's Rip Van Winkle , in: The Drama Review 26: 1, 1982.

- ^ Rip Van Winkle (1903 / I). Internet Movie Database , accessed May 22, 2015 .

- ^ National Film Preservation Board : Films Selected to The National Film Registry, Library of Congress .

- ^ Richard Hollis, Brian Sibley: Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and the Making of the Classic Film . Simon and Schuster, New York 1987. p. 5.

- ↑ David Thoreen, Thomas Pynchon's Political Parable: Parallels between Vineland and Rip Van Winkle , in: ANQ 14: 3, 2001, pp. 45-50.

- ↑ Erika Hulpke, Cultural Constraints: A Case of Political Censorship , in: Harald Kittel, Armin Paul Frank (Eds.), Interculturality and the Historical Study of Literary Translations , Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 1991, pp. 71-74.

- ^ Walter A. Reichart: The Early Reception of Washington Irving in Germany . In: Anglia - Journal for English Philology 74, 1956. P. 351.

- ^ Walter A. Reichart, Washington Irving's Influence in German Literature , in: The Modern Language Review 52: 4, 1957.

- ^ Max Frisch, Collected Works in Time Sequence , Volume 3: 1950–1956 , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1972, p. 422.

- ^ Philip Roth, Exit Ghost , Hanser Belletristik, Munich 2008, p. 1.