Arches National Park

| Arches National Park | ||

|---|---|---|

| Delicate Arch, the landmark of Utah | ||

|

|

||

| Location: | Utah , United States | |

| Next city: | Moab | |

| Surface: | 310.3 km² | |

| Founding: | April 12, 1929 | |

| Visitors: | 1,663,557 (2018) | |

| Address: | Arches National Park | |

| North Window (front) and Turret Arch (rear) at dawn | ||

The Arches National Park is a national park in the United States in the north of the Colorado Plateau in the Colorado River north of the town of Moab in the State of Utah . He maintains the world's largest concentration of natural stone arches (ger .: arches ) caused by erosion and weathering re constantly come and go again. Over 2000 arches with an opening of at least 90 cm (3 feet) have been identified in the park area. The ecosystems of the over 300 km² large park extend from the bank of the Colorado River to bare rock and are characterized by the average height of around 1500 m above sea level in a desert climate.

The area was placed under protection as a National Monument in 1929 and upgraded to a national park in 1971 . It is maintained by the National Park Service .

Geography and climate

The Colorado Plateau is an uplift that was created as a bulge by lateral tectonic forces. The park lies at an average of 1499 m above sea level, its highest point is the "Elephant Butte" in the east at 1696 meters. The deepest point of the park is 1225 meters in the south on the Colorado River , close to the park entrance and visitor center. The south of the park is characterized by canyon- like watercourses that are dry almost all year round, the rest of the area is a high plateau with several flat and wide valleys.

Climatically the area is a desert . In summer temperatures can reach 40 ° C, while in winter they can drop as low as −10 ° C. Fluctuations of more than 25 ° C within a day are not uncommon. The long-term mean precipitation is less than 200 mm. The low rainfall is due to the proximity to the Tropic of Capricorn , the high elevation leading to previous rainfall at the borders of the Colorado Plateau, and the interior location of the continent, which results in an extreme continental climate .

Average temperatures and rainfall on average over 15 years:

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Yearly | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Temp (° C) | 5 | 11 | 16 | 21st | 28 | 30th | 37 | 36 | 30th | 23 | 12 | 7th | 21st |

| Min Temp (° C) | −8 | −3 | 1 | 6th | 11 | 13 | 18th | 18th | 14th | 6th | −2 | −6 | 6th |

| Precipitation (mm) | 9 | 12 | 12 | 19th | 14th | 11 | 14th | 23 | 22nd | 29 | 17th | 17th | 196 |

geology

The stone arches, because of which the area was placed under protection and which are the main attraction of the national park, are openings in rock ribs that are created by erosion without the participation of running water. They are thus separated from natural stone bridges.

Shift sequence

The high concentration of stone arches in the park area of 310 km² can be explained by the geology of the region. About 300 million years ago in the late Pennsylvania , which belongs to the Paleozoic Era , there was a saltwater-filled basin called the Paradox Basin at the site of today's park . In the hot and dry climate, even then, salt settled in the basin when water evaporated. Over several hundred thousand years, the basin must have been repeatedly filled with new salt water, as a result the up to 1,500 m thick Paradox Formation was formed from a salt layer that is criss-crossed by marl , clay , anhydrite and individual deposits of slate . It was covered by the Honaker Trail Formation of both limestone and sandstone. The latter arose from erosion products from the Uncompahgre Mountains to the east , a predecessor of the Rocky Mountains . It is only accessible at one point in the south of the park.

In the area of the Paradox Basin the rock strata from the Permian and Triassic periods from about 300 to 200 mya , which characterize the strata of the Grand Staircase in other parts of the Colorado Plateau, are largely missing ; they were locally eroded by intermittent erosion. Only a few deposits of the Cutler Formation from the Permian and the Moenkopi Formation as well as the Chinle Formation of the Triassic are present. Even from the beginning of the Jurassic around 200 million years ago, only thin layers have survived. They emerged from sand dunes which , driven by the wind, overlaid the exposed salt layers and, under the pressure of later layers , were condensed into Wingate sandstone over a long period of time . In a few places there is a thin layer of Kenyata sandstone, which was deposited as sands from alluvial fans . The layer of Navajo sandstone is important. It emerged from the compaction of dunes that were driven together by the wind. The resulting round shapes with overlapping structures in changing directions can be observed almost everywhere in the park on the immediate surface of the earth.

Around 150 mya at the end of the Jura it was again covered by heterogeneous sandy sediments, which became the Entrada sandstone formation. Your bottom layer is called the Dewey Bridge Member , and above it is the Slick Rock Member . Together they are known as the Carmel Formation . Above it lies the Moab member from the Curtis formation . All of the park's stone arches eroded from this rock, and almost all of them are in the slick rock layer. This layer was covered with around 1,600 m younger rock from the end of the Jura and from the chalk , which, however, is almost completely eroded in the park, but in the vicinity of the park as Summerville and Morrison sandstone, as well as from the chalk of the Cedar Mountain Formation , the Dakota sandstone and the Mancos - slate can be found. In the Quaternary , sediments were deposited on the Colorado River, and the park's surface is heavily characterized by unconsolidated sands derived from recent erosion and carried by the wind.

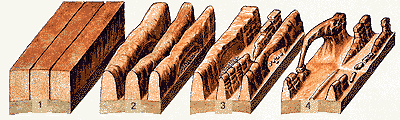

1. When the anticlines collapsed, the uplift cracks in the sandstone opened.

2. As a result of erosion, the surface of the cracks increased, which enabled the erosion to progress even more rapidly, so that long, rib-like structures emerged.

3. Rocks crumble and break through the ribs, in a few cases holes were made in the walls.

4. The holes created in this way are further eroded by wind and weather, water partially penetrates the sandstone and, when it freezes, blasts out more rocks.

Origin of the stone arches

The combination of subterranean salt deposits, the heterogeneous sandstone, and the great sea level with an extreme climate is responsible for the formation of the stone arches. Already in the Jura the salt layer was plastically deformed under the pressure of the rock layers above and formed a salt dome up to 3000 meters thick . It bulged in various places and formed elevations called anticlines . The forces acting from below broke crevices in the sandstone above. With elongated anticlines, these crevices ran parallel and could be several kilometers long.

As the tectonic uplift of the entire Colorado Plateau took place over the past 5 to 10 million years, the erosion accelerated. As a result, the Entrada and Navajo sandstones came close to the surface and water seeped into crevices. It reached the salt dome and slowly flushed it out. The rocks raised by the salt lost their foundation and slid down along the crevices. As a result, the cracks at the edge of the former anticline broke and the crevices became wider. Between them ribs arise (Engl. Finn ) of stone. There are two valleys in the park that arose from the collapse of such elongated anticlines, Salt Valley and Cache Valley . The vast majority of the Arches are located at their edges, the area called Fiery Furnace with most of the young and small Arches at their intersection.

A stone arch is created in particular where sandstone of different composition lies on top of one another in a rib and the lower layer is softer. This often applies to the transition from Dewey Bridge Member to Slick Rock Member when the softer Dewey sandstone begins to crumble. If this happens from both sides of a rib and breaks through the Dewey layer, a stone arch can arise. As Arch only those openings, the largest diameter exceeds three feet (90 cm) shall apply.

If the arch is no longer stable, it collapses. As the process of erosion continues today, this fate will eventually overtake every arc. The Wall Arch , then the park's twelfth largest arch and located directly on the popular Devils Garden Trail , collapsed between August 4th and 5th, 2008.

In the park you can see the different stages in many places. The other rock formations appear and disappear in the same way.

Ecosystems

Arches National Park is located in the ecoregion "Semiarid Benchlands and Canyonlands ", part of the Colorado Plateau. It is characterized by highland grass , shrub and forest communities and differs from the lower arid canyon zones in its altitude . The landscape is characterized by layers of layers and river terraces in which table mountains and canyons with steep slopes lie. In many cases the bedrock is open . The bottom is young stripping of sands. Typical plants are grasses, goosefoot , seaweed , Atriplex canescens , a melde and sagebrush . Pine and juniper trees prefer locations with flat, stony soils.

Throughout the park you can see turkey vultures ( Cathartes aura ) and white-breasted swifts ( Aeronautes saxatalis ) flying in the sky. Over 270 species of birds have been observed in the park so far, including migratory birds and casual visitors.

Over 50 species of mammals have been identified or accepted in the park. Most of these are rare or only occur in small populations. Common are just a few rodents and bats . The largest permanent mammal in the park is the mule deer ( Odocoileus hermionus ). Desert bighorn sheep ( Ovis canadensis nelsoni ) can only be seen in the south of the park near the Colorado . Occasional visitors are the pronghorns ( Antilocapra americana ).

Around 18 species of lizards and snakes live in the park, and they mainly feed on insects and small mammals. They themselves represent an important food for birds of prey and predators. They are very well adapted to the drought and heat of the desert and fall into a hibernation in winter when it is extremely cold .

The six-lined racing lizard ( Cnemidophorus tigris ) and the common spotted iguana ( Uta stansburiana ) are frequent and noticeable . In contrast, the snakes that live in the park are mostly nocturnal. The two poisonous snakes dwarf rattlesnake ( Crotalus oreganus concolor ) and prairie rattlesnake ( Crotalus viridis ) are rather rare. The striped whip snake ( Masticophis taeniatus ) is conspicuous, non-toxic and common .

Around 10% of the park area is grassland, around 40% loose woodland and 50% without closed vegetation. In addition, there are small-scale special locations, such as the bank zone of the Colorado, spring outlets and rock depressions that are only seasonally filled with water.

Grasslands

Grasses grow all over the park, except for bare rock locations. They form closed stands on around 10% of the area and are referred to as grassland. The two grasses that shape the landscape are Galleta and blue grama ( Bouteloua gracilis ), both sweet grasses from the subfamily of the Chloridoideae . Other species that are widely represented in the park are Indian ricegrass ( Oryzopsis hymenoides ), several species from the genus Sporobolus and the roof brine , which was introduced into the American West as a neophyte and which has spread particularly on soils that have been damaged by overgrazing . Until 1982, areas within the national park were still grazed, so that the grassland ecosystems of the park have changed significantly compared to their natural state. In the grasslands there are cinnamon-bellied phoebetyrants ( Sayornis saya ), black throats ( Amphispiza bilineata ) and the western larkbird ( Sturnella neglecta ).

Woodland

Loose woodland of pinyon pine , especially Pinus edulis and Utah juniper, is the most common plant community in the park . Wherever deeper soils have formed or crevices in the rock allow tap roots to penetrate , individual or grouped trees of these species grow, with juniper being a little more common than pines. The vegetation is loose, and around 90 other plant species grow underneath and preferably in the shade. Another tree that forms the stand is Acacia rigidula , which, due to the harsh climate in the park, hardly reaches a height of more than a meter and colonizes mostly flat soils, but also overgrows sand dunes in suitable locations if they do not migrate for a long time. In this case, Acacia rigidula can further fortify the dunes. In the pinyon juniper forests one encounters the black- billed jay ( Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus ), the western bush jay ( Aphelocoma californica ) and the black warbler ( Dendroica nigrescens ).

Loose occurrences of mugwort and sarcobatus species grow in suitable locations, mugwort predominantly on loose sand, sarcobatus in places with particularly salty soils.

Open locations

Almost half of the park is largely ungrown. This includes both bare rock and open sand. Of particular importance are cryptogams , which can form thin crusts on both rock and sand. On sand in particular, they reduce evaporation and protect against erosion. In this way they can stabilize dunes and drifts. They also enrich the soil with nitrogen .

Special locations

The park extends in the southeast to the Colorado River and includes its bank, this is characterized by steep rock walls, so that the river and its water resources only characterize the immediate bank zone. Originally there was a gallery forest made of willows . In the meantime it is being largely displaced by immigrant tamarisks . The river is an important corridor for bird migration in the Utah deserts . Great blue herons ( Ardea herodias ) can be seen here in spring . Ospreys ( Pandion haliaetus ) and bald eagles ( Haliaeetus leucocephalus ) as well as various other birds of prey are also guests in the park at this time. Among the songbirds, the azure bishop ( Passerina caerulea ), the yellow-breasted warbler ( Icteria virens ), the red chalk bunting ( Pipilo erythrophthalmus ) and the canyon wren ( Catherpes mexicanus ) use the Colorado valley as a migration route.

Spring outlets form hanging gardens in some sheltered rock niches with ferns , mosses and water-loving flowering plants such as primroses , columbines and juggler flowers . Amphibians like the Rotpunktkröte ( Bufo punctatus ) and the New Mexico - blade ( Spea inter montana ), Northern leopard frog ( Rana pipiens ) and Tiger Salamander ( Ambystoma tigrinum ) use the source outlets as a habitat. The bullfrog ( Rana catesbeiana ) was introduced into the area by humans.

Of particular importance for a large number of living beings in the park are, only temporarily, pools in rock depressions after the short rainy season. There are gill pods that live in a constant race against time after the rare summer rains. They must complete their complete reproduction cycle before the pools dry up. Once the eggs have been laid, they can wait years and decades for the same pond to fill up with water again.

flora

General

The flora of the Arches National Park is characterized by various adaptations to the desert climate due to the very difficult living conditions in terms of drought and extreme temperatures. They can be divided into three ecological groups:

- The first group includes the drought escapers (for example: "Dürremeider"). These are plants that only appear when the living conditions are optimal. The seeds of these plants can rest for years until they are germinated by moisture . Most grasses and wildflowers belong to this group .

- The second group are the drought resistors (about: "Drought-resistant"). Thanks to special adaptations, they are able to withstand the heat and drought. They usually have very small leaves in order to offer very little surface for evaporation . These include succulents such as cacti as well as yucca plants and mosses , which can dry out completely without dying off.

- The drought evaders (for example: "drought fleeing") live in habitats in which the living conditions are not so extreme. They can be found on the courses of the rivers or in shaded places near springs.

In addition to the climatic conditions, the soil also plays a major role, and the vegetation changes depending on the nature of the soil and its chemical properties. For example, deep, nutrient-rich soils are usually covered with grass, sandy and nutrient-poor soils with bushes. The pinyon juniper forests, which are the dominant flora of the Arches National Park, are found mainly on stony soils.

trees and shrubs

Trees and shrubs need sufficient water and nutrients to grow. For this reason, they are usually very small and widely dispersed in arid areas such as Arches National Park. However, once they are established they are very persistent. Their roots jagged the stony ground in search of water and nutrients, and even prolonged periods of thirst do not bother many shrubs. Many of the trees and shrubs that live in desert areas are over a hundred years old.

The most common shrubs in Arches National Park include the Mormon tea , the blackbrush ( Coleogyne ramosissima ), the four-wing saltbush ( Atriplex canescens ) and the cliff rose ( Purshia mexicana ). Large parts of the park also contain the loose populations of pinyon pine ( Pinus cembroides ) and Utah juniper ( Juniperus osteosperma ), which are dominant at altitudes between 1,500 and 2,000 meters in the southwestern United States. The proportion of juniper increases at higher altitudes as it is more competitive there.

The species diversity of the trees is highest in the area of the river corridors, as they have plenty of water here. Here you can find the nettle hackberry ( Celtis reticulata ), the ash maple ( Acer negundo ), the narrow-leaved olive ( Elaeagnus angustifolia , also "Russian olive"), small-flowered tamarisk ( Tamarix parviflora ) and Fremont cottonwood ( Populus Fremdontii ). The Russian olive and the tamarisk are not originally native to the USA ( neophytes ), but they are very successful in the area of rivers.

Wildflowers, grasses and cacti

Most of the flowering plants and grasses in the desert areas are annuals, which means they germinate, bloom and multiply within a year. Especially in the very hostile deserts, this vegetation period can be very shortened. Many of these plants can remain in the ground as seeds or tubers for years until optimal living conditions prevail for them, for example after heavy rainfall. In Arches National Park these usually occur in the months of April to May, but they can also be absent.

All plants must also be particularly well adapted to the heat and aridity of the desert areas. The flowering plants have accordingly thick layers of wax on the leaves and stems as well as very small leaves to reduce evaporation. The roots are either very deep or very large in order to be able to absorb as much water as possible. Some flowering plants, such as the yucca plants , the evening primrose (genus Oenothera ), the blue thorn apple ( Datura meteloides ), Wright's thorn apple ( Datura wrightii ) and the sand verbenia (genus Abronia ), also only bloom in the cooler evening hours. Specifically, the Yucca styles are in their resume very closely with specific pollinator, in this case with the prodoxidae linked.

Grasses can be found in Arches National Park wherever the sand is saturated with slightly more nutrient-rich soil. All desert grasses can be divided into two groups based on their growth habit: the tufted grass and the turf grass. Tufted grasses include all those that grow in scattered patches, such as Indian rice grass ( Oryzopsis hymenoides ) and needle-and-thread ( Stipa comata ) in Arches National Park . Both are perennial, although rice grass is known to be over a hundred years old. Galleta and Blue Grama ( Bouteloua gracilis ) are native to the park among the lawn-forming grasses , which mostly form common areas and are important as food for the bighorn sheep and deer. The roof bromide ( Bromus tectorum ), which was introduced by chance in the 19th century , is also widespread .

Cacti have become a symbol for the desert plants of North America. There are also nine species of this group of plants in Arches National Park. They belong to the group of succulents and have thickened trunks or branches and spines or scales instead of leaves. Their surface is covered by a wax to prevent evaporation. The root network is usually flat and wide, so it can absorb water very quickly. When it rains heavier, additional "rain roots" grow, which later wither again.

Cryptogams

The most inconspicuous, but at the same time one of the most important components of the flora are the cryptogams , i.e. all mosses , liverworts and lichens as well as the so-called "cryptobiotic crusts".

Lichen can be found in numerous types as a colorful coating on a great many stones, especially those that are exposed to sunlight. These are symbioses between fungi , green algae and blue algae , which are very well adapted to the conditions in the desert. In this way they can still produce biomass even when it is very hot ( photosynthesis by the algae, protection and nutrient supply by the fungi).

Mosses respond to the extreme conditions of the desert by allowing them to dry out completely for long periods of time without dying off. You can find them in almost all habitats in the park, especially on shady stones and the areas of the river corridors. It is Syntrichia caninervis the most common type on the cryptobiotic crusts Grimmia orbicularis makes 80 percent of the moss vegetation from on stones. Liverworts, on the other hand, always need water and can therefore only be found in the river areas.

The cryptobiotic crusts represent the basis of life for all plants and animals in many areas of the national park. It is a "living substrate", which mainly consists of blue-green algae, but also contains mosses, lichens, green algae, fungi and bacteria . Blue-green algae in particular ensure that the soil is enriched with nutrients, as they fix nitrogen from the atmosphere in the soil in a form that can be used by plants. In addition, they hold the soil together with their foothills and thus protect it from erosion to a depth of ten centimeters.

history

Early history

The first human traces in today's national park date from the end of the last ice age over 10,000 years ago. The area is rich in flint and chalcedony . However, traces of agriculture can only be found 8,000 years later. The remains of fields where corn , beans and pumpkins were grown were discovered. However, there is no evidence of human habitation from this period. It is believed that the population at that time lived near Four Corners , the joint border of the four states of Arizona , Colorado , New Mexico and Utah not far from the park, and only cultivated the fields in Arches National Park. The population is attributed to the Fremont People or the ancestors of the Pueblo builders . They lived in buildings similar to those that can still be admired in Mesa Verde today. Although no housing was found, there are numerous rock carvings from this period. The descendants of the pueblo builders still live in pueblos today, for example the Hopi Indians. The Fremont People were contemporaries of the Pueblo builders and the differences between the two cultures have not yet been adequately explored. Both cultures left this area almost simultaneously about 700 years ago.

Paiute Indians settled here, but the period of settlement is completely unclear. The first encounters with this tribe took place in 1776. Rock carvings were also found that are attributed to the Paiute, as these show hunting scenes with Indians sitting on horses. However, horses were only introduced by the Spaniards during colonization.

White colonization

The first whites to come to this area were Spaniards . The first recorded date comes from the trapper Denis Julien. He had a habit of scratching his name and date in stone wherever he hunted. The oldest find in the park dates to June 9, 1844.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (" Mormons ") established a mission in 1855 called the Elk Mountain Mission , now Moab. Through numerous conflicts with the Ute - Indians but they had to abandon their plan again quickly. In the years 1880 to 1890 the abandoned mission was successfully settled by farmers, trappers and prospectors. But only a few tried to settle the desert-like area north of the city. Temperatures of up to 40 ° C combined with only rare water points made this seem not very successful. Only the building of a ranch by John Wesley Wolfe, a veteran of the American Civil War, is documented, who settled in 1898 with his eldest son Fred in the area of today's Delicate Arch Trail. In 1906 he was followed by his daughter Flora with her husband and children, who, however, moved to Moab in 1908. Wolfe sold his ranch to Tommy Larson in 1910 and moved back to Ohio, where he was from.

The area became famous through Loren “Bish” Taylor, who took over the newspaper in Moab in 1911 and repeatedly reported in his newspaper about the beauty of the region north of Moab. He was often accompanied by the first doctor in town, John "Doc" Williams. The place where the two were often to watch the area is still called Doc Williams Point today.

The news of Taylor got around, and so in 1923 the gold prospector Alexander Ringhoffer wrote to the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad to open up this area for tourism. He accompanied those responsible for the railway company in this area, who were so impressed that a project was immediately started to attract tourists by placing the area under protection, who would make better use of the railway line.

History of the park

Based on the plans of the railway company, President Herbert Hoover declared the region a National Monument on April 12, 1929 in order to protect the many natural wonders. On November 25, 1938, Franklin D. Roosevelt enlarged the area. In 1960 and 1969 the park was enlarged again and on November 12, 1971 Richard Nixon named it a national park. Another small expansion took place in 1998 under Bill Clinton .

Until the 1960s, the then National Monument was hardly developed. The writer Edward Abbey worked as a ranger in the area for several summers and wrote the book Desert Solitaire (1968), which was influential for the American conservation movement, on his experience of the wilderness . It ends with the development of the sanctuary for tourism as part of Mission 66 of the National Park Service, during which around one billion dollars was spent on infrastructure and tourist facilities in parks on the occasion of the 50th year the service was founded.

The national park today

Attractions

- The Delicate Arch (height: 65 feet, corresponds to almost 20 meters) in the eastern part of the park ( ⊙ ), 2.5 km from the Wolfe Ranch (approx. 1 hour walk) is a secluded, very well-known arch. One of the images bears the license plate of the state of Utah. Frank Beckwith, leader of the Arches National Monument Scientific Expedition , gave the arch its current name in 1933. At that time, the arch was not part of the park until it was enlarged in 1938. Around 1950, the arch should be provided with a kind of plastic coating to protect it from further erosion and destruction. But the National Park Service remembered its original goals of protecting nature from humans and protecting it from their influence, but otherwise leaving nature to its own devices.

- The Three Gossips (three gossips) can be seen as the first prominent rock group after entering the national park to the left of the road. On the top of the structure you can see three heads, each looking in a different direction.

- The Babel Tower is located in the south of the park directly across from the Three Gossips and was featured with them on a Marlboro poster in the early 2000s .

- The Sheep Rock at the end of a rock face looks like a ram and is likely the remnant of a collapsed arch.

- The balanced rock is a large rock that "balances" on a rock needle. It is close to the road and can be circled on foot on a 500 meter path.

- Double Arch consists of two large arches that are almost at right angles to each other. He can be seen briefly in the films Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and the Hulk .

- Skyline Arch is almost at the end of the street. When a rock broke out of the arch in 1940, the size of its opening doubled.

- The Landscape Arch is one of the largest arches in the world with a span of 92 meters. On September 1, 1991, a boulder 18 meters long, 3.40 meters wide and 1.20 meters thick broke from the bottom of the arch. Since then it has been less than 3 meters thick at its thinnest point.

- The Partition Arch is a few hundred meters behind the Landscape Arch. It does not impress with its size (compared to the other arches in the park, it is rather small), but with the spectacular panoramic view of the La Sal Mountains , which you can get from there Has.

- The Double-O-Arch consists of two superimposed arches. It can only be reached via a long, unsecured rock ridge in the last section of the path. The hike there is therefore only recommended if you are in good physical condition and have sufficient time and water supplies.

- The Fiery Furnace is a walk-in labyrinth, which is formed by huge sandstone ribs.

administration

The reserve is wholly owned by the US federal government and administered by the National Park Service, an agency under the umbrella of the US Department of the Interior. The park administration employs its own scientists from various disciplines and shares others with geographically and thematically neighboring protected areas. In cooperation with external research institutions, continuous biomonitoring programs take place and threats to the national park are investigated.

Protection status

Arches National Park is in an almost untouched natural state, so only minor measures are required. Tamarisks have migrated to the reserve along the Colorado River and Salt Creek, which has only seasonal water in the south and east of the park . They have been fought with mechanical means since the turn of the millennium because they disrupt the water balance of the desert soil. The national park is a member of the Dark Sky Coalition, an association to investigate and combat light pollution in the night sky through artificial lighting in neighboring locations. The Arches National Park is one of the places with the darkest night sky, where a particularly large number of stars are visible, due to the altitude and the drought, as well as the distance from population centers . This status is endangered by population growth in Moab and the surrounding area, as well as particles in the air from coal-fired power plants in the area.

Plans for the construction of another coal-fired power plant in Sigurd and the development of areas in the vicinity of the park for prospecting for oil , natural gas and uranium are considered a threat . The surrounding land is administered by the Bureau of Land Management , like the National Park Service, an agency under the umbrella of the US Department of the Interior whose task is primarily the commercial exploitation of federally owned land. The two authorities are arguing about the use of the land and the resulting dangers for the national park. Active and abandoned mines also threaten the water quality of the Colorado River in the reserve.

tourism

The park is accessed by a spur road from which branches lead to several outstanding areas. The most famous rock arches can be reached by short hiking trails from the streets, the Devils Garden with the greatest concentration of distinctive arches is accessible by a nearly ten kilometer long hiking trail.

The park has no designated hiking trails (trails) in the hinterland, so hikes off the main routes are only suitable for visitors who have a good knowledge of navigation and experience in deserts. Registration at the visitor center is required. For the undeveloped Fiery Furnace area in the center of the park, guided hikes are offered daily from February to October. Because the rock structures there are particularly sensitive, visitors need a separate permit to access the Fiery Furnace on their own, which can also be obtained from the visitor center. Visitors are given an introduction to how to behave in the brittle sandstone. Free climbing in the park is generally allowed, since 2006 all rock arches ("Arches" and "Natural Bridges") that have a proper name on the official maps, as well as some individually blocked formations, have been excluded. Climbing and abseiling is prohibited on them to protect the landscape.

At the end of Parkstrasse there is a small campsite with 52 parking spaces and little comfort. That is why only around 47,000 of the over one million visitors a year stay overnight in the park itself. Accommodation of all classes is available in Moab and the surrounding area.

Balanced Rock , behind the La Sal Mountains

literature

- Edward Abbey: Desert Solitaire. A Season in the Wilderness . McGraw-Hill, New York 1968.

- David William Johnson: Arches. The story behind the scenery . KC Publications, Las Vegas 1987, ISBN 0-88714-002-5 .

- Eugene P. Kiver, David V. Harris: Geology of US Parklands . John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY 1999, ISBN 0-471-33218-6 .

- Stanley W. Lohman: The Geologic Story of Arches National Park (= Geological Survey Bulletin 1393) . US Gov. Print. Off., Washington, DC 1975 ( [1] ).

- National Park Service (ed.): Arches (= German leaflet) . ( PDF ).

Web links

- National Park Service: Arches National Park (official site; English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Arches National Park in the United States Geological Survey's Geographic Names Information System

- ^ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Deserts , accessed June 11, 2012

- ↑ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Weather (accessed April 11, 2009)

- ↑ Naturalarches.org: FAQ (accessed April 11, 2009)

- ↑ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Geologic Resource Evaluation Report (PDF; 1.5 MB)

- ^ DL Baars, HH Doelling: Moab salt-intruded anticline, east-central Utah . In: Geological Society of America, Centennial Field Guide - Rocky Mountain Section , Volume 2. Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society of America, 1987, ISBN 0-8137-5406-2 , pages 275-280

- ↑ Eugene P. Kiver, David V. Harris, pp. 506 f.

- ↑ Lohmann 1975, text = Chapter 8 .

- ↑ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Natural Features (accessed April 11, 2009)

- ↑ National Park Service: Wall Arch Collapses - August 8, 2008 press release (accessed April 11, 2009)

- ↑ The description is based on: US Environmental Protection Agency: Level IV Ecoregions of Utah (accessed December 28, 2009)

- ↑ United States Geological Society: Arches National Park - Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report , 2009.

- ↑ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora (PDF; 745 kB), 2009.

- ↑ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Species Checklist Birds ( Memento from July 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Species List Mammals ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Species List Reptiles ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d Johnson 1987, chapter The Mosaic of Life , pages 22-37

- ^ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Grasses

- ↑ a b c National Park Service: Arches National Park - Birds

- ^ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Soils

- ↑ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Species List Amphibians ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Ephemeral Pools

- ↑ The presentation is based on: National Park Service: Arches National Park - Plants (accessed on April 11, 2009) and Johnson, Chapter The Mosaic of Life , pages 22 ff.

- ↑ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Soils (accessed April 11, 2009)

- ↑ USGS: Cryptobiotic Soils: Holding the Place in Place , May 18, 2004

- ↑ This chapter draws on National Park Service: Arches National Park - History and Culture (accessed April 11, 2009)

- ↑ Arches National Park: Research Permits 2007 (PDF; 158 kB) - overview of ongoing research projects and preliminary results, status 2007 (accessed on April 11, 2009)

- ^ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Environmental Factors (accessed April 11, 2009)

- ^ National Parks Conservation Association: Coal-fired Power Plants threaten the Southwest's National Parks ( Memento from August 20, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Salt Lake Tribune, Lease sale riles Park Service , Nov. 9, 2008

- ^ National Park Service: Arches National Parks - Geology Fieldnotes , booth; January 4, 2005

- ^ National Park Service: Arches National Park - Plan Your Visit (accessed April 11, 2009)

- ↑ National Park Service: Public Use Reports, 2010 Statistical Abstract (PDF; 949 kB)