Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine ( Occitan Aleonòr d'Aquitània , French Aliénor or Éléonore d'Aquitaine ; also Éléonore de Guyenne ; * around 1122 in Poitiers in Poitou ; † April 1, 1204 in the Fontevrault monastery in France ) from the House of Poitiers was Duchess of Aquitaine , by marriage first Queen of France (1137–1152), then Queen of England (1154–1189) and one of the most influential women of the Middle Ages .

Eleanor came from the dynasty of the Dukes of Aquitaine , successors to Carolingian kings of Aquitaine and ruler of the largest duchy on French soil. Through the marriage of Eleonores to the French heir to the throne Louis , the French crown succeeded in re-tying territorial lords that had become increasingly independent and autonomous since the Carolingian era . The dissolution of the marriage with Louis VII is considered to be one of the most momentous separations in history, as it set in motion a development that led to more than 300 years of conflict between the English and French kingdoms. Shortly after the annulment of the marriage with the French king, Eleanor married the young Heinrich Plantagenet , the Duke of Anjou and Normandy , who was also a candidate for the English crown. Two years later, Henry and Eleonore were crowned English monarchs. Henry's policy was aimed at consolidating the territories owned by the family into what is now known as the Angevin Empire . The territorial rulers that Eleanor brought into the marriage again played a key role. However, her biographer Ralph V. Turner points out that Eleanor's actions show that she felt called to be the heir to the throne of Aquitaine and entitled to rule her own duchy and determined to prevent it from being stripped of its own identity and into that Would be incorporated into her husband's kingdom.

The marriage between Eleonore and Heinrich was fraught with conflict, not least because of Eleonore's right to exercise power independently. After Eleanor had joined the rebellion of three of her sons against their father in 1173/1174, Heinrich placed them under house arrest for 15 years. After the death of her husband in 1189, during the reign of her two surviving sons Richard Löwenherz and Johann Ohneland , she again assumed an important political role.

Myths and legends began to form around the person of Eleanor during her lifetime. She was accused of adultery with her uncle. For many centuries she was the example of a power-hungry, scheming ruler. This picture has changed a lot in the last few decades. Not least after she found her way into popular culture through the film The Lion in Winter , she became the main character of numerous works of fiction , which she stylized as a patroness of poets and minstrels , for which the historical sources, however, do not offer any reference to this extent. The overall meager sources make it difficult to do justice to the historical person Eleanor. Historians like Ralph V. Turner see her will to assume her role as queen and her determination to uphold the integrity of her Duchy of Aquitaine as the leitmotif of their lives.

Surname

According to Gottfried von Vigeois , Eleanor of Aquitaine was baptized with the name Alienor. According to this chronicler, this baptismal name is derived from alia-Aenòr ("the other Aenòr") in order to distinguish her from her mother. However, in view of the different spellings of the name in documents and contemporary chronicles, the historian Daniela Laube points out that the exact form of the name was not fixed during Eleonore's lifetime and the name was used differently. Abbot Suger calls them Aanor, Morigni's chronicle Aenordis; later she is called Alienor, sometimes also called Helnienordis. The form Eleonore , which is common in German-speaking countries, is used here.

swell

No contemporary of Eleonores left written evidence that would correspond to a biography in today's sense. Sources about her life are to a large extent annals and chronicles , which were mainly written by clergymen or, more rarely, by secular scribes from the royal court. Only very few chronicles have survived from Eleanor's Duchy of Aquitaine and these mainly focus on the events in the vicinity of individual monasteries. According to the judgment of the historian Ralph Turner, contemporary chronicles from the environment of the French royal court surprisingly little mention Eleonore's time at the side of Louis VII: Their reputation had suffered so much that the clergy apparently tried to erase them from historical memory. The most important sources on Eleonore's life come from a group of English scribes. Secular writers in this group include Roger von Hoveden , Walter Map , Radulfus de Diceto , Giraldus Cambrensis, and Radulfus Niger . Roger von Hoveden and Radulfus de Diceto, who were close to the English royal court, judged Eleanor largely neutrally. Walter Map and Gerald von Wales wrote satirical texts about life in the English royal court, in which rhetoric and polemics often prevailed over the facts . Giraldus in particular, who had found no sponsor at the English royal court, polemicized in his writing maliciously and maliciously against all members of the Plantagenet family. In contrast, Radulfus Niger limited his judgmental criticism to Heinrich in his two chronicles.

Four other contemporary or contemporary writers were monastic chroniclers: Gervasius of Canterbury , Radulph of Coggeshall , Richard of Devizes, and William of Newburgh . The image that these monastic chroniclers paint of the royal family was influenced by the assassination of Thomas Beckett and led to the fundamental assumption that all members of the royal family lived an immoral way of life. Only Richard of Devizes admires the perseverance and consistency with which Eleanor stood up for Richard the Lionheart during his crusade. All church clerks shared a deep unease with Eleanor's claim to power. In the understanding of roles, any exercise of public power by a woman was "unfeminine" and thus unnatural and improper. Ralph V. Turner writes:

"So we need not be surprised that the image [the chroniclers] have left us of her is speckled with dabs of evil that have condensed into a permanent" black legend "over the centuries."

Family background and childhood

ancestry

Eleanor of Aquitaine paternal grandfather was Duke Wilhelm IX. of Aquitaine . He was married to Philippa of Toulouse , daughter of William IV of Toulouse , in his second marriage . Since Philippa's brothers both died childless, Philippa was the legal heiress of the county of Toulouse bordering Aquitaine , from which Eleanor's claim to this county later, which led to numerous conflicts, was derived. Philippa's uncle Raimund of Toulouse had usurped the county of Toulouse after the death of Philippa's father and Wilhelm only managed to recapture his wife's legacy for a short time before it reverted back to the Counts of Toulouse.

The court that Wilhelm IX. in Poitiers had a reputation for being one of the most cultured in Europe. He was a pioneer in a change in which the knightly offspring were instructed not only in the use of weapons, but also in courtly manners and possibly classical education. As a result, Eleanor grew up in an environment that differed considerably from the world of her two future husbands. From her grandfather, eleven in Langue d'oc wrote Minne songs handed down, which earned him the name "Troubador Duke". Half of these chants frivolously mock the strict sexual morals of the church. In fact, Wilhelm's life was marked by numerous extra-marital love affairs. The crucial extra-marital relationship for his granddaughter was that with the wife of his vassal Aimeric I, the Vice Count of Châtellerault , which began in 1115. Wilhelm kidnapped the mother of three children to his court in Poitiers, whereupon his wife withdrew to the Abbey of Fontevrault . The vice countess, who lived at Wilhelm's court for the next few years, wanted at least for her daughter Aenòr the official role of duchess and advocated marrying her daughter from her marriage to the vice count of Châtellerault to the eldest son of the duke. The marriage between the young Wilhelm and Aenòr de Châtellerault probably took place in 1121.

Childhood and youth

As the first child of Wilhelm and Aenòr, Eleanor was probably born near Bordeaux. Even if some sources state 1122 as Eleonore's year of birth, 1124 is now the more likely year. Eleonore's sister Aelith, who was later called to the French royal court Petronilla, was probably born in 1125 and in 1126 or 1127 the longed-for male heir Wilhelm Aigret followed. Eleonore's grandfather died in 1127 and her father took over the rule of the duchy. Eleanor's brother and mother died in 1130, making Eleanor her father's heir.

Unusually for her time, Eleanor learned to read both Occitan and Latin, but there is no evidence that she also learned to write. In addition, she presumably received instruction in needlework and housekeeping. The growing Eleanor was considered beautiful. However, none of the contemporary troubadours who so named it has given any clues as to what it actually looked like. The contemporary ideal of beauty called for blonde hair and blue eyes; a wall painting of the church of Sainte-Radegonde in Chinon , which was made during her lifetime and represents her with great certainty, shows a woman with reddish-brown hair. Her intelligence, wit and open-hearted nature, which many of her contemporaries found attractive, have been handed down.

Death of the father

The reign of Eleonore's father was short and marked by numerous disputes with his vassals and the church. Wilhelm X. initially supported the antipope Anaklet from 1130 onwards , and it was not until 1135 that he confessed to being Pope Innocent II through the influence of Bernhard von Clairvaux . The widower's plan to marry the daughter of Vice Count Adémar von Limoges , who would have strengthened his influence in the Limousin , failed in an intrigue of his vassals, who have revolted against the Aquitaine rule over their land for more than a century. Count Wilhelm von Angoulême kidnapped the young woman and married her. The feared revenge campaign by Wilhelm did not materialize, instead he joined a campaign by his northern neighbor Gottfried von Anjou in September 1136 . Either the events during this short campaign or the encounter with Bernhard von Clairvaux were the trigger that Wilhelm decided to make a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in order to atone for his sins. Before leaving, he made his vassals swear to respect Eleonore's claim to inheritance. At the same time he placed his daughters under the protection of his liege lord, King Ludwig VI. of France . His two daughters accompanied their father to Bordeaux, where he presumably left them in the care of the archbishop. Wilhelm died on Good Friday, April 9, 1137, shortly before he reached Santiago de Compostela.

Eleanor's legacy

Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis , the influential advisor to the French king, claims that in his will, William not only gave Eleanor into the care of the king, but also asked him to designate a husband for her. In his generosity, Ludwig then decided to marry his successor to the throne to Eleonore. This contemporary testimony, however, obscures the true motives: The death of Wilhelm and the possibility of his heiress marrying his heir to the throne Ludwig presented for Ludwig VI. primarily the possibility of binding essential French territorial rulers more closely to the throne. At the beginning of 1137, the French crown domain was essentially limited to Île-de-France , Orléans and part of Berry . A marriage between the heir to the throne and Eleanor would extend the immediate sphere of influence of the French crown to extensive and rich lands in central and southern France. According to the scanty evidence of rights and rulers, the feudal system in these areas was complex and regulated differently and it was unclear to what extent the French crown would succeed in enforcing its upper fiefdom in these regions. A marriage with the heiress of the Duchy of Aquitaine meant in any case a claim to areas beyond the Loire, in which the French crown had not owned a domain since the 10th century. In addition, Eleonores had a legal claim to the county of Toulouse. All of these lands would not immediately count towards the Crown Domain. A son from this marriage would also be the French heir to the throne and heir to these areas.

There is an indirect indication of the great importance that the French court attached to the marriage between the heir apparent and the Aquitaine heiress. After the death of her father, Eleanor was almost certainly in the care of the Archbishop of Bordeaux, whose protection ensured that she was not kidnapped by Aquitanian vassals and forced into marriage. In June 1137, the ecclesiastical province of Bordeaux was granted the privilege of electing its prelates by canonical election and of no longer having to take oaths of fief or allegiance to the French throne. At the same time, all existing possessions and privileges of the ecclesiastical province were confirmed. According to Daniela Laube, it is reasonable to assume that the Archbishop of Bordeaux received privileges over the extensive independence of his diocese in return for his protection of the duke's daughter.

Marriage to Louis VII.

Louis was destined to be Eleanor's husband and was the second-born son of the French king. He was originally intended for an ecclesiastical career and was educated accordingly in the Abbey of Saint-Denis . It was only when his older brother Philipp died in a fall from his horse in October 1131 that his father brought him back from the monastery to the French court. Although he had since been instructed in all the chivalric arts and had been included in government affairs by his father, the 17-year-old Ludwig was characterized by deep piety and reserved modesty.

Eleonore and Louis were married on July 25, 1137 in the Cathedral of Bordeaux . Immediately after their wedding, as Duke and Duchess of Aquitaine, they took the oath of feudal and allegiance from the Aquitanian vassals. Shortly after the wedding, they received the news of the death of Ludwig VI. On August 8, 1137, Louis VII was crowned, making him ruler of the French kingdom, the county of Poitou and the duchy of Aquitaine.

At the French royal court

The Palais de la Cité , the Capetian residence in Paris, was simple compared to the residences Eleanor had grown up in. Apparently Eleanor was dissatisfied with her accommodation, because in the winter of 1137 Ludwig gave the order to modernize and enlarge the queen's rooms. There is also evidence to suggest that Eleanor tried to reshape life at the French court according to the courtly life that she was used to. She introduced tablecloths and napkins as they were in the South, and the pages were instructed to wash their hands before serving meals. She had the cantor of the royal chapel of Saint Nicholas fired to replace him with one better able to lead the chapel's choir. Much of her and her behavior met with strong rejection: the entourage she had brought with her formed a clique around the young queen, who long-serving Capetian courtiers had to perceive as a threat to her influence. A detailed description of her and her ladies-in-waiting elegant clothing has been handed down, for example, because Bernhard von Clairvaux sharply condemned them as excessive luxury. Her public role was limited to a ceremonial one during the first decade of her marriage; only a few of Ludwig's edicts also bear her name. Her limited political influence distinguishes her from her mother-in-law and other French queens before her and is almost certainly due to Ludwig's advisors, who specifically sought to limit Eleonore's influence.

During his marriage, Ludwig led a life that was strongly influenced by his monastic youth. Usually reserved and modestly dressed, he devoted a large part of his day to prayer, assisted at masses and only ate water and bread on Fridays. Politically, he continued his father's work by trying to consolidate the crown domain and try to keep the influence of his vassals under control. He also tried to make the administration of the French kingdom more efficient. Few doubted his personal integrity and in the course of his life he acquired a reputation for approaching the chivalric ideal. The most important advisor in his early reign was the ascetic abbot Suger, who had already served his father and, under Bernhard von Clairvaux's influence, had renounced all courtly luxury.

Reports by contemporary chroniclers such as Johannes von Salisburys from 1149 show that Ludwig had a deep affection for his wife. But it is also relatively certain that Ludwig and Eleanor did not often share the marriage bed with each other. The church teaching forbade sexual intercourse on Sundays and the numerous public holidays as well as during Lent and probably the deeply religious Ludwig adhered to these regulations. Eleonore had a miscarriage in the first or second year of marriage, after which there was no further pregnancy. It was not until the year 1145 that Eleanor gave birth to a viable child for the first time. It wasn't the heir hoped for, though. The girl was christened Marie.

Failed plans

In 1141 Ludwig undertook a first campaign to recapture the county of Toulouse, which had been ruled for 20 years by Alfons Jordan of Toulouse and which Eleanor claimed as her inheritance. Ludwig did not prove to be a skillful general during this campaign. The forewarned Alfons Jordan had Toulouse fortified strongly in anticipation of the French army, and since Ludwig did not bring enough siege equipment with him, the French king had to break off his campaign without result. Ludwig also showed political clumsiness in appointing the Archbishop of Bourges . Louis refused entry into Bourges for Pierre de La Châtre , appointed by Pope Innocent II , and when the Pope asked the king's ministers to prevent their masters from continuing to behave as foolishly as a schoolboy, Louis swore an oath on relics that the Archbishop-designate Bourges would not enter while he was alive. Pope Innocent then excommunicated Ludwig. This excommunication represented a heavy punishment for both deeply religious Ludwig and the citizens of his royal cities. In no city or castle in which he resided, bells were allowed to ring, church services or church funerals and baptisms or marriages were allowed. It is not clear what part Eleanor had in this affair. The decisive factor is that Pope Innocent suspected that Eleanor had driven Ludwig to take this position.

Her younger sister Petronilla lived in Eleonore's household. In the summer of 1141, the 16-year-old began an affair with Raoul de Vermandois , 35 years her senior , who was married to Eleonore, sister of Theobald IV of Blois . In the winter of 1141/1142, Ludwig found three well-meaning bishops who annulled Raoul de Vermandois' existing marriage because they were too closely related by blood and then married him to Petronilla. Theobald von Blois not only took his sister Eleanor and her children into his household, but also protested to Pope Innocent against Ludwig's interference in a matter that was to be decided by the Church alone. Theobald found support from Bernhard von Clairvaux, who was shocked to Pope Innocent about the crime against the Champagne family and the sacrament of marriage.

At a council ordered by Pope Innocent in June 1142, the papal legate excommunicated Cardinal Yves, one of the three bishops involved in the marriage annulment, suspended the other two from their office and ordered that Raoul de Vermandois return to his wife. When Raoul refused to do so, both he and Petronilla were excommunicated and their territory was placed under interdict . Ludwig refused to recognize the decision of the papal legate, which he interpreted as an attack on his royal authority and began a campaign against Theobald, whom he accused of being to blame for this development.

Campaign in Champagne

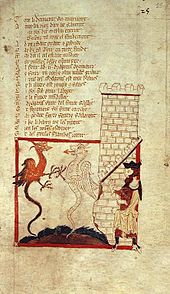

The feud between Ludwig and Theobald lasted until 1144 and was only settled through the mediation of Abbot Suger and Bernhard von Clairvaux. The Champagne was severely devastated in many parts during this Kriegszugs. The Vitry-le-François catastrophe was decisive for Ludwig's further decisions : marauding soldiers of Ludwig invaded the city, plundered it and set some of the houses on fire. Part of the population, according to the chronicles between 1000 and 1500 people, sought protection from the marauders in the cathedral. The fire raging in the city spread to the roof of the cathedral, which collapsed and buried the people who had taken shelter in the cathedral. Ludwig, who witnessed the catastrophe from a hill, did not order the sacking of the city, but felt responsible for the deaths of these people.

One of the declared critics of the campaign in Champagne was Bernhard von Clairvaux, who warned the French king in numerous letters that he was jeopardizing his soul and challenging the wrath of God. Bernhard also warned Ludwig of advisors who would lead him astray and went so far as to call them enemies of the French crown. Since both Abbot Suger and other advisers had warned Ludwig about the campaign in Champagne, it was clear that Clairvaux's harsh words referred to Eleonore, her sister Petronilla and Raoul de Vermandois. During a direct encounter, Bernhard Ludwig verbally attacked the assembled court society so violently that Ludwig was overwhelmed by feelings of guilt to such an extent that his doctors feared for his life. The successor to Pope Innocent, Pope Celestine II , lifted Ludwig's excommunication, but the Vitry disaster and the confrontation with Bernhard changed Ludwig permanently. Ludwig had his hair sheared like a monk's, began to wear simple clothing in a monk-gray color, fasted three days a week and spent hours of the day in prayer to ask God for forgiveness.

The thoughtless political behavior of Ludwig during his first years of marriage contrasts with the later exercise of power. In the literature, his behavior is therefore often attributed to the influence of Eleanor, even if this cannot be proven. The Vita prima of Bernhard von Clairvaux also assumes such an influence from Eleanor , which suggests that Eleanor opposed Bernhard's efforts for peace and that a peace agreement was only possible after she had given in.

The disputes about the marriage of Eleonore's younger sister Petronilla and the subsequent campaign in Champagne led to the first question that the legality of the marriage between Eleonore and Ludwig was questioned. The Bishop of Laon was the first to point out the close relationship between the two spouses and Bernhard twice in his disputes with Ludwig took up the question of why Ludwig was dissolving his seneschal's first marriage because he was too close by blood , while he himself did not is less closely related to Eleanor.

crusade

Call to the crusade

In 1144, Emir Imad ad-Din Zengi conquered the county of Edessa , one of the four original Crusader states . The news of this recapture aroused concern throughout Christian Europe as it highlighted the threat to the land gains of the First Crusade . On December 1, 1145, Pope Eugene III. a bull in which he urged King Ludwig and all Christians in France to come to the aid of their fellow believers in the Holy Land. A similar bull was directed at the Roman-German King Konrad III.

Ludwig was on another crusade , not least because he saw in it a reparation for the disaster in Vitry and the possibility of a restoration of his reputation. At Christmas 1145, during the Christmas court meeting, he announced that he was planning to retake Edessa. Among the ranks of opponents of such a crusade was Abbot Suger, who warned Ludwig that he would serve God better if he stayed in France. To Abbot Sugar's concern, Eleanor had also declared that she wanted to follow her husband to the Holy Land. Ralph Turner stresses, however, that there were strong political reasons not to leave Eleanor alone in France. As queen, she would have held a strong position of power, perhaps even assumed the office of regent , and thus could have questioned the powers of Abbot Suger, who, according to Ludwig's will, was to rule the French kingdom during his absence. Eleonore's participation was also the guarantee that nobles would pull out of their territorial rule and that the churches and the townspeople maintained their promised generous financial support for the crusade.

On Easter Sunday, March 31, 1146, Bernard of Clairvaux preached in the open field and urged the assembled crowd to join the crusade. Ludwig and Eleonore were the first to take the cross. There is no evidence in contemporary sources that Eleanor was criticized for her decision to join the crusade. It was not until fifty years later that chroniclers like William of Newburgh suggested that women following a crusade did so for reasons other than spiritual. Gervasius of Canterbury claims that Eleanor and her ladies dressed in white tunics adorned with red crosses after Bernhard von Clairvaux's sermon and then galloped through the assembled crowd on white horses with drawn swords and waving banners. As a sign of cowardice, they would have tossed spindles to those of the assembly who were still reluctant to do the same . Most historians dismiss this story as a legend because there are no contemporary sources for this event. However, it was already believed to be credible by people who Eleanor had met in the last years of her life and the historian Alison Weir points out that it seems appropriate to the character Eleanor, who the chronicle has passed down.

Failure of the crusade

In mid-June 1147 the crusaders set out from Metz . Eleonore and Ludwig traveled separately from each other. At night the court chaplain Odo de Deuil and the court official Thierry Galan shared the tent with the king, while Eleanor traveled in the company of her ladies and vassals. Later chroniclers have accused Eleanor and her noble ladies of behaving as if it were a pleasure trip during this phase of the crusade. In contrast, Eleonore's behavior is hardly mentioned in contemporary sources. The legend that Eleanor was accompanied by a cohort of mounted and armed “ Amazons ” is not historically proven. The report of such "Amazons" in Eleanor's entourage appeared for the first time in a Greek chronicle that described the entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople . However, this chronicle was only written down at least one generation after the event, taken up by authors of the 19th century and further disseminated in later, much-read books about Eleanor. It is undisputed that the large number of women and the accompanying entourage impaired the fighting strength of the crusader army .

Assaults on the population in the parts of the country through which the crusaders passed showed during the first week of this crusade that Ludwig was only able to enforce his orders among the crusaders to a limited extent. Failure to follow orders ultimately led to the fact that the crusaders in Asia Minor were attacked by a Turkish army while crossing the mountain Honaz Dağı (then called Cadmus) and were decisively weakened. The main sources for the events on Mount Honaz Dağı are reports by Odo von Deuil and William of Tire . The more detailed report comes from Odo von Deuil, who names the Aquitan nobleman Gottfried von Rancon and Count von Maurienne, an uncle of Ludwig, as the commander of the armed vanguard . Against the order of the king, the vanguard began to cross the Honaz Dağı when they had reached the foot of the mountain around noon and enemy forces had not shown up until then. The vanguard moved further and further away from the main group of crusaders, which was followed by an armed rearguard under the orders of Ludwig. When the Turkish army attacked the main force, only Ludwig could attack with his rear guard and was devastated. William of Tire reports the events on Mount Honaz Dağı in much less detail. He only names Gottfried von Rancon as the person responsible. Eleanor is not mentioned in either of the two chronicles. Reports of the crusade that emerged later claim, disregarding the main sources, that it was Eleanor, traveling with the vanguard, who caused Gottfried von Rancon to act differently than ordered.

Stay in Antioch

In March 1148 Ludwig arrived in Antioch with a tenth of the original crusader army and was received there by Raimund von Antioch , a younger brother of Duke Wilhelm X. of Aquitaine and thus an uncle of Eleanor. Seven years older than Eleonore, he had married the heiress of the Principality of Antioch Konstanze in 1136 and has been at the head of the principate ever since.

Raimund hoped that Ludwig would support him in his campaigns against Aleppo and Hama , while Ludwig planned to leave for Jerusalem as soon as possible . Eleanor appears to have sided with Raimund and his military plans on this matter, which led to increasing disagreement between the two spouses. When Ludwig was preparing to leave, Eleanor expressed the wish to remain in Antioch with her Aquitanian vassals. The most reliable contemporary source of the events in Antioch in 1148 is the account of John of Salisbury. He writes in detail:

“While the king and queen remained [at Antioch] to comfort, heal, and revive those who had survived the fall of the army, the attention the prince paid to the queen, and his permanent ones, did indeed attract almost incessant conversations with her the mistrust of the king. This was greatly intensified when the Queen expressed her wish to stay, although the King was preparing to leave, and the Prince went to great lengths to keep her if the King gave his consent. And when the king exerted pressure to tear her away, she mentioned their consanguinity and said that by law they could not remain man and woman since they were related in the fourth and fifth degrees. "

Wilhelm of Tire indicates in his Historia the possibility of Eleanor's adultery with Raimund. However, this chronicler wrote his Historia four decades after the events, when the Duchess's reputation was already very poor. According to Daniela Laube, the chronologically written report of John of Salisbury would have been less neutral in its choice of words had there been proven adultery of Eleanor. Ralph Turner, on the other hand, points out that for contemporary clerics like John of Salisbury the real violation of Eleonore was already in her refusal to submit to the serving role that was expected of a wife. Her persistent advocacy of her uncle's plan and her lack of discretion in the process already constituted infidelity because she thereby compromised her husband's royal dignity. Turner also points out that the accusation that the queen defied her husband's authority and thereby disregarded the Christian commandment of submission to the woman quickly turned into suspicion of committed adultery with her uncle. Even contemporary troubardor poems contain allusions to this alleged adultery.

Ludwig finally forced Eleanor to travel with him to Jerusalem. On the return trip to France in April 1149 Pope Eugene III succeeded. first to reconcile the two spouses. Eugene III. confirmed the royal marriage orally and in writing and forbade them ever to speak of their blood relationship again. In fact, the degree of blood relationship between Eleonore and Ludwig is controversial and was apparently already during their lifetime. The Pope's attempt at reconciliation was initially successful. Eleanor gave birth to a second daughter in 1150, about a year after returning from Jerusalem and five years after the birth of Marie .

Separation from Ludwig VII and marriage to Heinrich Plantagenet

On January 13, 1151 Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis died, who had strongly encouraged Ludwig to keep his marriage to Eleonore. 15 months later, on 21 March 1152, the marriage between Eleanor and Louis at the Council of was Beaugency in the presence of several archbishops canceled . Several witnesses had previously confirmed the close blood relationship between the spouses, which Pope Eugene had denied three years earlier. Since a protest on the part of the Curia in Rome has not survived, it is possible that Bernhard von Clairvaux urged the Pope to have it canceled. The main reason for the separation was that after fifteen years of marriage no heir to the throne was born. This also indicates that the two later wives of Ludwig, Constanze of Castile (who also did not bear him a son) and Adele of Champagne , were more closely related to him than Eleanor.

Ludwig became the guardian of their daughters, Marie and Alix. Eleanor got back the lands that she had brought into the marriage. The cancellation made it possible for both Eleonore and Ludwig to remarry. As Ludwig's vassal, Eleanor would theoretically have required Ludwig's consent before a new marriage. The attempt by both Theobald von Blois and Gottfried von Anjou to intercept Eleonore on her journey to Poitiers and to marry her by force, however, makes it clear that several high nobility of France were willing to risk a campaign by Louis in order to acquire Eleonore's extensive inheritance to get. Eleonore married neither of the two, but on May 18, 1152, without the consent of her ex-husband and liege lord, Heinrich Plantagenet , who was eleven years his junior , Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy .

The sources give only a few indications as to how the connection between Eleonore and Heinrich came about. Alison Weir and Ralph Turner are convinced that the meeting and agreement that was decisive for the quick marriage took place in August 1151, when Eleanor was still married to Ludwig and Heinrich was in Paris on the occasion of negotiations with Ludwig. The connection made sense for both Eleonore and Heinrich: After the marriage annulment, Eleonore was not only threatened by violent marriage initiation, but also needed a strong partner in order to assert her claim to power in their areas. Heinrich was also one of the few appropriate spouses who were even considered. Marriage to Eleanor would greatly increase Heinrich's resources with which he could pursue his claim to the English throne. Eleonore's legacy would more than double Henry's dominion on the European continent; the area from the English Channel to the Pyrenees , which would be directly under his rule, which had been augmented by their inheritance , encompassed half of what is now France and was ten times the size of the French crown domain of that time. Against the marriage with her spoke that she would possibly provoke back reactions and thus tie Henry's armed forces on the European continent, which he needed to enforce his claims in England. Heinrich also needed heirs, but Eleonore, who is now 30 years old, had only given birth to two girls.

Marriage to Heinrich II.

1152-1166

Ludwig initially refused to recognize Heinrich's claims to Aquitaine. However, there were no formal provisions in feudal law that Heinrich would have violated by his marriage to Eleonore so clearly that he could have been punished for it with the confiscation of his territorial possessions. Nevertheless, it took a few military and diplomatic interactions before Ludwig, who had meanwhile been remarried, officially renounced the title of Duke of Aquitaine in August 1154. At this point in time Wilhelm , the first son from Eleonores' marriage to Henry, had already been born and the English King Stephen had recognized Henry as his rightful heir to the throne in the Treaty of Wallingford .

Queen of England

Stephen of England died in October 1154 and on December 19, 1154 Henry and Eleanor were crowned by Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury at Westminster , London. The support that Heinrich originally had from the English barons was based not least on their hope that they would keep their freedoms and rights, which had been usurped over the years, under a predominantly nominal rule by Heinrich. However, Heinrich managed to largely enforce his authority in England by the end of 1155. The Pipe Rolls reveal that Eleanor enjoyed a great deal of trust in the early years of the marriage. For example, she was able to arrange payments from the state treasury on her own and, in the absence of her husband, she ruled for years in England, where she lived most of the time. Her orders (so-called "writs"), which she issued in close cooperation with royal officials who enjoyed Heinrich's trust, had the same legal force as instructions from the king. Ralph Turner points out in particular that Heinrich obviously had enough confidence in Eleanor to leave her there alone in the critical early years of his reign in England, when his rule over this kingdom was not yet consolidated. Shortly after the beginning of his English rule, he transferred some of the traditional widow estates of the Anglo-Norman queens to her. She owned 26 benefices scattered across 13 English counties . Their earnings amounted to an amount equal to that of the richest earls or barons in the kingdom.

Married life

Heinrich spent most of the year traveling alone through his territories and usually met Eleanor on the occasion of the Christmas court. Eleanor usually traveled to the European continent with some of her children. It is documented that the couple saw each other at Christmas 1156 in Bordeaux, 1157 in Woodstock and Oxford , 1158 in Cherbourg , 1159 in Falaise , 1161 in Le Mans , 1162 in Bayeux and 1163 in Cherbourg.

The first-born son Wilhelm died in 1156, but four more children were born by 1158: Heinrich (1155), Mathilde (1156), Richard (1157) and Gottfried (1158). In 1158, however, Ludwig was still without male descendants. At a meeting between Ludwig and Heinrich towards the end of 1158, the two monarchs concluded a marriage contract that provided for a marriage between the English heir to the throne, Heinrich, and Margaret of France, who was born in 1158 . Should Ludwig no longer produce male descendants, the Plantagenets could claim a legitimate claim to the French crown. As was customary for young female nobles at the time, Margarete, who was not yet a year old, was handed over to her future father-in-law for upbringing. Ludwig only made it a condition that his daughter should not grow up in his ex-wife's household. As Margarete's dowry, the two kings had agreed on the Norman Vexin , whose castles were of great importance for the control of the traffic routes between Paris and Rouen. In view of the age of the two engaged children, Ludwig certainly did not expect this dowry to be due anytime soon. Heinrich managed, however, by Pope Alexander III. to receive a dispensation for the marriage of the two children even though they were far too young for it under canon law. In November 1160 the two and five year old children were married to each other.

The initially good relationship between the two monarchs suffered further damage when Heinrich tried in vain to assert Eleonore's claim to the county of Toulouse in 1159. The course of the eastern border of the Duchy of Aquitaine was also controversial and not only Heinrich and Eleonore, but also the Counts of Toulouse and the Capetians made claims on the County of Auvergne. Until 1166, however, there were no major military conflicts between Ludwig and Heinrich. In view of the overwhelming superiority of his vassal, Ludwig concentrated on the expansion of the crown domain and an alliance policy from which his son Philipp August, born in 1165, was to benefit significantly.

1165 and 1166 Eleanor and Heinrich celebrated the Christmas days separately, which some historians see as the beginning of the estrangement between the two spouses. In addition, the heir to the throne Heinrich no longer lived in the care of his mother, but received his own household and increasingly represented at the side of his father. After two daughters, who were born in 1162 and 1165, Eleonore gave birth in December 1167 as the last child from their marriage to Heinrich Johann .

Rebellion of the Sons

Eleanor returns to Aquitaine

In 1167 Heinrich was busy suppressing various revolts of his vassals. At this point Eleanor seems to have taken over the rulership of Aquitaine together with Patrick, Earl of Salisbury . There is evidence of an attack on the Earl of Salisbury and Eleanor on March 27, 1168, which probably took place on the road between Poitiers and Niort and in which the Earl was killed. Guy de Lusignan wanted to take Eleanor hostage with this attack in order to strengthen his negotiating position with Heinrich. Eleonore just managed to escape from this attack.

From the point of view of the historian Alison Weir, it made political sense that Eleanor, with Henry's consent and under his sovereignty, began to exercise rulership in their inherited territories that had been under foreign rule for three decades. During her travels through her dominion, she accepted, among other things, the fiefs of Aquitan nobles in Niort , Limoges and Bayonne , re-established old markets, encouraged exiled barons to return and confirmed the ancestral rights of cities and abbeys. After Richard von Devizes , Eleonore's decision was made in these years to continue to live separately from Heinrich and to remain forever in their inherited territories. As further evidence of this there is a letter from the Archbishop of Rouen , Rotrou von Warwick, after it was Eleanor who also decided not to live with her husband any longer. Some historians argue that Henry's affair with Rosamund Clifford was the reason for this separation. Against this is the fact that Eleanor had previously ignored Heinrich's numerous affairs, from which several children had emerged. There are also many indications that this affair only began after Eleanor's return to France and that it was only noticed in public when Eleanor was already a prisoner of her husband. Weir thinks it is more likely that the age difference between the two partners became increasingly clear and that their strong-willed characters made them incompatible with one another. Turner, however, points out that there were long periods of separation in earlier years of the marriage between Eleanor and Heinrich. He argues that another explanation for Eleanor's return to Aquitaine could have been her desire to exercise her inherited claim to rule in Aquitaine herself and also to regulate the succession of this duchy in her favor. Her return also comes at a time when her role as regent in England had become increasingly unimportant after Heinrich had built up a functioning administrative apparatus there. As the heiress of a dynasty older and more famous than Henry's Angevin and Norman lines, Eleanor also refused to allow Aquitaine to become part of the Plantagenet empire. This is also supported by the fact that Eleanor used formulations in her decrees and instructions in 1171 that underlined that she ruled in Poitou and Aquitaine in her own authority and not only as Henry's representative.

The Montmirail Treaty

The Treaty of Montmirail, concluded at the beginning of 1169, regulated for the first time how his inheritance should be divided up after Henry's death. The eldest son of the royal couple, Heinrich, was to take over the rule in England and, in addition, Normandy and Anjou should fall to him. He was crowned King of England in 1170 - the coronation of the heir to the throne while the father was still alive was a common step to secure the succession. Richard was to receive Aquitaine, his supreme liege lord would accordingly be the French king. Gottfried was to keep Brittany and thus become a vassal of his eldest brother. The youngest son Johann was initially disregarded. It is not known how much Eleanor was involved in her husband's plans for the succession. That her duchy, which was brought into the marriage, should go undivided to Richard, should have been in Eleonore's sense. The procedure was also not unusual: the primogeniture had not yet fully established itself and there were conventions according to which the property that the woman had brought into the marriage with a prince went to the second-born son in the event of inheritance.

1172 followed the investiture of Eleanor's son Richard as Duke of Aquitaine. According to the chronicler Gottfried von Vigeois, this was done at the request of his mother. However, real power remained with Henry II. Richard, for example, had to turn to him if he needed more money for troops. Eleonore, however, granted her son Richard a share in political responsibility. On the other hand, the situation of his older brother Heinrich was more difficult. His father decided not to give his eldest son any part of government responsibility. Despite the coronation, Heinrich had no land of his own and thus no income of his own. The murder of Thomas Beckett by four knights from the court of Henry II had discredited the king in the eyes of his son, who had spent part of his youth at the court of Beckett. When Heinrich II began to divert a territorial inheritance for his youngest son Johann, who had initially not been considered, at the expense of the three older sons, this led to a rebellion of the older sons against Heinrich, which grew into a broad uprising movement. As early as the beginning of 1173, Raymond von Toulouse informed Heinrich about a conspiracy between his wife and his eldest sons. The rebellion became apparent to everyone when the young Henry fled to the court of the French king, who was his father-in-law, in March 1173. Richard and Gottfried joined their brother a little later. Eleonore was imprisoned in November 1173 by followers of Henry on the way to Chartres.

Contemporary chroniclers such as Ralph of Diceto , William of Newburgh, and Gervase of Canterbury believe that the Sons rebellion was initiated by Eleanor. Only a few, such as the author of the anonymous Gesta Henrici Secundi, see Ludwig as the main driver behind the conspiracy, the aim of which was to overthrow Heinrich II. A number of historians, such as Elizabeth Brown and Ralph Tuner, point out that there were valid political reasons for Eleanor to support the rebellion: in 1173, her husband managed to settle with Raymond of Toulouse, who gave up his formal vassalage to Castile and Limoges Henry II and his son Heinrich paid homage.

“In accepting Raymond's homage to Toulouse, Henry betrayed, in Eleonore's eyes, her long-standing claims to Toulouse as part of her rightful inheritance, and sowed doubts that the county was a vassal state of Aquitaine. At the same time he recognized Raymond [...] as the rightful ruler of Toulouse and implicitly suspended Eleonore's claim to the county. The fact that he accepted the Count's homage was all the more worrying for Eleanor as she knew that his claim to suffrage over Toulouse resulted solely from his marriage to her. Finally, she interpreted Count Raymond's homage to the young [Heinrich] as a step that suggested a sovereignty of the English crown over the Duchy of Aquitaine - in her eyes a signal that Richard and his descendants would in future receive their title of duke by the grace of the English king should wear. Eleanor, however, wanted the direct transfer of rule over Aquitaine to Richard, without the English king as an intervening liege lord. "

Captivity of Eleanor

It took Heinrich II until 1174 to put down the rebellion of his sons, supported by Ludwig, against his sovereignty. However, there were no actual campaigns, the military clashes were limited to the siege of castles and the burning of towns and villages of the respective enemy.

Eleanor, initially held captive at Chinon Castle , was transferred to England in the summer of 1174. Thereafter, Eleonore is only mentioned a few times in contemporary chronicles until Heinrich's death in 1189. The mentions do not indicate that Eleonores was actually imprisoned; in Ralph Turner's view, her situation can best be described with the term house arrest. It is relatively certain that her household was initially very small. In 1177/1178 the Pipe Rolls show expenses for coats and pillows for the queen's household, the same happens in 1179 and in this year a gold-plated saddle is also booked for the queen. Further evidence shows a meeting with her daughter Mathilda, who is married to Henry the Lion , in Winchester, a stay of the Queen and Henry the Lion in Forcester and Portsmouth and a crossing of the two on Henry's ship to France. Daniela Laube evaluates the increased evidence during her daughter Mathilda's multi-year stay in England to the effect that Eleonore was granted more freedom of movement during these years. After the duke and ducal couple returned to Germany in 1185, however, there is no evidence that Eleanor appeared in public.

The relatively good treatment of Eleonore, which she received during the almost 16 years of her imprisonment, is, according to Ralph Turner, a rational act of her husband. Inconsiderate treatment would have further strained his tense relationship with his three eldest sons and made the exercise of power in Eleonore's duchy much more difficult. Even higher would have been the political price that Heinrich - who was already blamed for the murder of Beckett - would have paid Eleanor in the event of a suspicious death. Heinrich II tried, however, in 1175/1176 to have his marriage annulled. It is not certain whether this ultimately failed because of the resistance of the Roman Curia or whether Heinrich became aware of the political consequences of such a cancellation.

Several contemporary chroniclers suggest that Heinrich began a relationship with Alice of France after the death of his longtime lover, Rosamund de Clifford . The connection was scandalous in every way. Alice was Ludwig's daughter from his second marriage and had been engaged to Heinrich's son Richard since 1169. Since the engagement she lived in Heinrich's care. It is possible that Heinrich was still convinced at the beginning of this relationship that he would have the annulment of the marriage with Eleonore and marry Alice instead of her. Both Ludwig and later his son tried repeatedly to enforce that the marriage between Alice and Richard would be consummated. The matter caused disagreements between the two royal families after Henry's death and ultimately remained unsolved.

Arguments between Heinrich and his sons

After the rebellion was put down in 1174, Richard was again given control of the Duchy of Aquitaine by Heinrich and until the death of his eldest brother in 1183, the cooperation between father and son seems to have been problem-free. The death of young Heinrich on June 11, 1183 changes this again. After the Treaty of Montmirail Richard would now fall to England, Normandy, Anjou, Poitou and Aquitaine. Gottfried - who was to die in 1186 either as a result of illness or an accident - was heir to Brittany, whereas Johann would only inherit Ireland and some goods in England and on the continent. Heinrich wanted to change this line of succession in favor of his youngest son, and Richard was to cede to Johann Aquitaine and Poitou, a project that Richard was initially able to evade. In 1185 Heinrich was able to force a cession of the duchy to Eleanor, who had come from England for this purpose. It is not known to what extent this return was made with Eleonore's consent. Richard then lived for some time at Heinrich's court and it is certain that this also applied to Eleanor at times. In the spring of 1186, for example, she held court with Henry in Normandy and traveled with him to Southampton in April. When Heinrich refused to officially recognize Richard as an heir in November 1188, the latter fled to the court of the French king and asked him for help. The alliance between Richard and Philipp August immediately led to acts of war in which Heinrich had nothing to oppose the combined forces of Philip August and Richard. Heinrich was finally forced to a peace treaty on July 4th, in which he had to recognize Richard as his main heir. Heinrich died a few days later near Chinon.

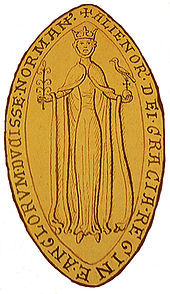

Queen mother

With Heinrich's death, Eleonore's withdrawn and largely uninfluential phase of life ended. During the remaining 15 years until her death in 1204, periods of relative seclusion alternate with periods of frenetic activity. Both Richard and Johann gave her priority over their own wives in their respective reigns and granted her the privileges of a neighbor queen. Her new role is also reflected in her seal that she had made after her release. It depicted her with more regal insignia than her two older seals, and referred to her as the queen by the grace of God.

Reign of Richard the Lionheart (1189–1199)

Richard, who had spent most of his life on the European continent, was largely unknown to his English subjects at the time of his father's death. Eleanor, who was released from arrest immediately after the news of Henry's death, immediately began to organize a smooth transition of rule over the kingdom. This included, among other things, the solicitation of oaths of loyalty in Richard's name and the appointment of court officials. “It is unlikely that a king ever received more valuable support from his mother than Richard von Eleonore,” says Ralph Turner of this transition phase. Richard thanked her by confirming her widow's estate, which Heinrich II had given her and also stating that she was entitled to everything that Heinrich I and Stephan had given their royal wives. It is unclear whether and how the income from the Duchy of Aquitaine was divided between Richard and Eleanor. In any case, Eleanor had an income that allowed her to hold a royal court as well as numerous foundations and gifts.

Third crusade

Richard had already committed to participating in the Third Crusade in 1187 and, a few months after his coronation, summoned his mother, his brother Johann, his half-brother Geoffrey Plantagenet and several archbishops to a council to regulate how his kingdom should be governed during his absence . His younger brother Johann would have been an obvious choice as regent. Richard mistrusted his brother, however, and even made him a vow (later revoked) that he would not step on the soil of England during his absence. Richard appointed William Longchamp as Chief Justice of England instead of Johann and, months later, made his nephew Arthur his heir.

Eleanor did not exercise any direct government functions at the beginning of the crusade. Instead, Richard had asked her to pick up Berengaria from Navarre in Spain and bring him to Sicily as a bride. In the summer of 1190, Eleanor, who was at least 66 years old, embarked on the arduous journey to Spain, where she had to convince King Sancho that Richard would in fact break off his long-standing engagement to the half-sister of the French king in favor of the Princess of Navarre. On March 30th, Eleanor, accompanied by the young bride, arrived in Reggio, Calabria, and then crossed to Messina , where she briefly met her youngest daughter Johanna. Only three days later she set out on her return journey to England, where a military test of strength threatened between the increasingly self-important Wilhelm Longchamps and her power-hungry youngest son Johann. The conflict ended with William Longchamps being ousted and Johann appointed heir to the throne of Richard if the marriage with Berengaria did not result in a son. This was in the spirit of Eleanor, since from her point of view her grandson Arthur was too close to the French royal court. However, Johann was barred from participating in the government affairs of the kingdom, which, with Eleanor's support, were largely transferred to Walter von Countenance. For Johann this was unsatisfactory and the French king, who had already broken off his participation in the Third Crusade in September 1191, tried to shift the balance of power in his favor by offering Johann the marriage to Alix, who had been cast out by Richard, and all French dowries Richards promised possessions. Only the influence of Eleonores and a number of noblemen at the court of the Plantagenets initially prevented Johann from accepting this offer from Philip Augustus.

Imprisonment and Return of Richard

For almost a year there was a precarious peace. Then at the beginning of 1193 the news arrived in England that Richard on his way back from the Middle East was first imprisoned in Germany by the Babenberg Leopold V of Austria and a little later to Emperor Heinrich VI. had been handed over. Johann reacted to this changed situation by immediately rushing to the court of the French king to pay homage to Philip August for his brother's French possessions. The assembled council of England rejected John's demand for the kingdom and until Richard's return to England there was a series of fighting between John's mercenary army and English troops on English soil.

At the end of 1193, the Bishop of Bath brought the terms that Emperor Henry linked to the release of Richard. As a crusader, Richard was under special papal protection and there are three contemporary letters written in the name of Eleonores with which she asks for papal help. It is disputed among historians whether these letters were sent in Eleanor's name or whether they are rhetorical finger exercises that were by no means set up on their behalf. The presumed author of the letters is Petrus von Blois , who accompanied Eleanor on her return trip from Sicily and then at least temporarily belonged to her court. Real or spurious, they express a mother's growing despair over the inaction of the Holy See. At the time, Pope Celestine was too keen to have a good relationship with the Roman-German Emperor to mess with him about Richard's capture.

Given the inaction of the Pope, Eleanor concentrated on obtaining the 150,000 marks that the Roman-German Emperor demanded as a ransom for Richard's release. Richard had not only authorized Eleanor to collect the required amount, but also stipulated that she should deliver the first installment of the ransom of 100,000 marks and accompany the hostages, whose position was to secure the payment of the second partial sum. In the winter of 1193/1194, Eleanor traveled to Germany accompanied by Hubert Walter , Archbishop of Canterbury. In January it finally reached Speyer . Richard recognized the suzerainty of the emperor for his kingdom of England. Heinrich demanded from Philipp and Johann, under threat of military force, the return of all possessions that had been confiscated from Richard during his captivity. This solution had the advantage for Heinrich that he had won Richard as a vassal , but at the same time Richard continued to fight against France as an independent English king, which meant that Philipp August was also dependent on Heinrich as an ally. The Kaiser cleverly maneuvered himself into a mediator position between England and France. On February 4, 1194 Richard was a free man again and on March 13, he landed in England with his mother.

In April 1194 Eleanor took part in Richard's second coronation in Winchester and she also seems to have been present at the reconciliation between Richard the Lionheart and his brother Johann. For the remainder of Richard's reign she retired to Fontevrault Abbey in Anjou.

Eleonore's last years during the reign of Johann Ohneland

Richard and Berengaria's marriage remained childless. As Richard's successors, Eleonore's youngest son Johann and her grandson Arthur were the primary candidates . Arthur's mother Konstanze had refused to let her son grow up at Richard's court due to her dislike of the Angevin ruling family, and when Richard demanded guardianship over Arthur in 1196, he was secretly brought to the court of the French king. It is possible that Eleonore was involved in this situation in appointing her grandson Otto von Braunschweig , the son of her daughter Mathilde , as Richard's heir. Otto, who had already been enfeoffed with the county of Poitou, preferred in 1197 to press ahead with his candidacy for royal dignity in the northern Alpine part of the empire.

When Richard was wounded by a crossbow bolt or an arrow during the siege of Châlus Castle on March 25, 1199 and died of this injury a few days later, he left a controversial legacy. There were as yet no binding rules as to which degree of kinship had priority in the case of inheritance, but some authorities took the view that a nephew as a descendant of a deceased older brother had a higher right than a surviving younger brother. In this situation, Eleonore did everything possible to get her son Johann recognized as an heir. Together with Richard's mercenary captain Mercadier , she led a punitive expedition to County Anjou, which Arthur had recognized. She also traveled to Aquitaine to obtain the support of her vassals for John. She also made sure that an armed conflict between the French and English kings would not spill over to the Duchy of Aquitaine while she was alive. To ensure this, Eleanor exchanged documents with her son, with which she appointed him as her rightful heir, bequeathed her territory to him and transferred the oaths of loyalty and feudal duties of all bishops and secular vassals to him. In return, Johann again issued a certificate with which he returned her dominion to her. Eleonore and Johann thus had joint power of disposal over their territory. However, since only Eleanor took the feudal oath towards Philipp August, a French military campaign in their area in the event of a dispute with Johann was humanly excluded. At the same time, she had cemented her son's position in the south-west of France by exchanging documents and made a potential intervention by Philip August in favor of Arthur after her death much more difficult. Ralph Turner describes the legal constellation that was brought about by these measures as a diplomatic masterpiece.

The acts of war between Johann and Philipp August were actually limited to Normandy and were ended in 1199 by the Treaty of Le Goulet . The two opponents agreed on a marriage of the French heir to the throne Ludwig with a princess from the house of Anjou-Plantagenet. Eleanor, now very old, undertook to travel to Navarre to pick up the chosen bride, her granddaughter Blanka of Castile , and to accompany her to France. Eleanor then withdrew to the Fontevrault Abbey, which she had been promoting for a long time . Eleanor, however, had to see how her son's clumsy behavior led to the disintegration of the Angevin Empire. Between 1200 and 1203 she made out at least ten documents relating to Aquitanian affairs, and through her personal intervention ensured that Count Aimery von Thouars was initially loyal to Johann. When her now 15-year-old grandson Arthur moved into Poitou at the head of a force in the summer of 1202, she was forced to leave Fontevraud for Poitiers to prevent Arthur from making a successful campaign. In July 1202, however, Arthur's armed forces succeeded in locking Eleanor and her followers into Mirebeau Castle . Johann's troops caught the besiegers by surprise by acting unusually quickly, prevented Eleonore's capture and also took Arthur prisoner. Arthur died in April 1203 while imprisoned in Rouen, presumably he was murdered on Johann's orders. The rumors about Johann's involvement in the death of his nephew led to the fact that numerous nobles of the Loire Valley, Anjou and Poitou parted ways with Johann.

Eleonore died on April 1st, 1204 at the age of about 80 years. In the same month Philip Augustus's troops occupied the Norman capital. Eleanor was buried next to her husband Henry II and her son Richard the Lionheart in Fontevrault Abbey.

effect

Effect on contemporary literary arts

Both Heinrich and Eleonore grew up in courts with a rich cultural life and, in Ralph Turner's assessment, a uniquely productive literary culture flourished among them at the English royal court. A large part of the works created in the environment of the English royal court were writings that underlined the sanctity of Henry's predecessors on the English royal throne. However, there is no evidence that the royal couple commissioned these writings directly. Turner believes it is more likely that authors whose writings attracted positive attention at court were indirectly rewarded by enabling them to enter a church career, being offered a position as royal scribe, or the monastery to which they belonged was given a special benefit. Philippe de Thaon, for example, initially dedicated his bestiary to Adelheid von Löwen , one of Eleanor's predecessors on the English throne. In 1154 he presented Eleanor with a copy that contained a new dedication addressed to her. In a few lines of verse of this dedication, he asks Eleanor to intercede with the king that he would be awarded his maternal inheritance.

Several verse narratives were also written in the vicinity of the English royal court; the most famous of these are the Roman de Brut , the Roman de Rou , the Roman de Troie and the Roman de Thèbes . An English translation from the beginning of the 13th century claimed that the novel de Brut by the poet Wace , written in Norman scripta and completed in 1155, was dedicated to Eleanor. Here, too, Turner points out that the dedication is no indication that Eleonore was commissioned. However, the dedication allows at least the conclusion that Eleonore was interested in literature and that the author could hope for a favor on her part. The Roman de Rou, on the other hand, is a work commissioned by Heinrich. Among other things, it contains a short biography of Eleonore, in which she is described as noble, friendly and clever. In no case do the sources suggest that Eleanor was a particular patron , and there is little historical evidence for this.

Eleanor of Aquitaine and her eldest daughter Marie de Champagne were and are often named as patrons of troubadour poetry . This is characterized, among other things, by the fact that it stylizes love into an ideal of platonic love , which stands above all for the inviolable knightly service for a lady, the submission to her will and the solicitation of her favor. In the 12th to 14th centuries, love increasingly stood for the “fin'amors” or “amour courtois” ( courtly, noble love ) of the Romanesque knight culture. The persistent legend that Eleanor promoted this courtly love in particular by gathering young women into a so-called "court of love " during her years in Poitou and taking on the role of arbiter in matters of love among these women, is based on only one source . Andreas Capellanus wrote De amore , a breviary for courtly lovers, in the second half of the 12th century , which among other things allegedly contains judgments in matters of love made by Eleonore and her ladies-in-waiting. Her eldest daughter is named as one of Eleonore's ladies-in-waiting at this love court in Poitou. However, there is no evidence that Eleonore saw her daughter Marie again after her separation from Ludwig. Recent discussions in the history of literature consider it likely that the portrayal of this court of love should be read as satire or an intellectual gimmick. This also indicates that two judgments ascribed to Eleanor contradict each other.

Effect on contemporary sculpture

The fact that the Abbey Church of Fontevraud developed into the burial place of the Plantagenets is due to the fact that the summer heat of 1189 did not allow the corpse of Heinrich II to be transported to the Grandmont monastery in Limousin, which Heinrich had chosen as his burial site. Instead, he was buried in Fontevraud. This abbey had long-standing ties to the Aquitaine ruling family. Eleonore's grandmother Philippa of Toulouse had withdrawn here when her husband, William IX. Aquitaine, his adulterous relationship with the Vice Countess de Châtellerault began. Under Eleonore's influence, Fontevraud then developed into the central burial place of her family. Both her son Richard and her daughter Johanna were buried here, and Eleanor was also buried here.

Ralph Turner assumes that Eleonore was instrumental in the work on the grave sculptures for Heinrich and Richard. The sculptures that were made for her husband and son are among the earliest grave figures of deceased rulers, which were carved life-size in stone in medieval Europe and are considered to be groundbreaking for the development of sepulkral sculpture . Turner also thinks it possible that Eleanor was involved in the design of her own tomb. As with the Gisants of her husband and son, Eleanor is depicted with a crown. Other symbols of royal power are missing. Unlike her husband and son, however, her Gisant portrays her alive, as a middle-aged woman. The reclining sculpture is also an artistic innovation, because it is the oldest medieval sculptural representation of a secular woman holding an open book in her hand.

Legends

Daniela Laube takes the view that Eleonore's bad reputation has its starting point in the events in Antioch, which are elusive for contemporaries.

“The triggering factor for this is that Wilhelm von Tire - discreetly veiling, but lending the unspeakable all the more weight through the unspoken - accused Eleanor of adultery. This laid the foundation stone and the development continues dynamically. No later medieval author was unaware of Eleanor's misstep; none who in his writings would not have called the Queen more or less sharply accountable for this. The attitude of the story is fixed until the end of the 19th [century]. "

While the earliest sources are still largely neutral about Eleanor, slightly more recent sources expand these suggestions to malicious further allegations. The chronicler Giraldus Cambrensis, for example, claims in his De instructione principis that Eleonore had already committed marriage to Heinrich's father Gottfried von Anjou and mentions his tenure as Seneschal of France as the period. Gottfried von Anjou never held this office. Although he was the Seneschal of Poitou, it is only known from this time that he held the office before 1151. In English historiography, reports of alleged adulteries of Eleonores were spun on by Roger von Wendover and Matthäus Paris and further developed by later chroniclers. The fact that Eleanor's adultery was the reason for separating his marriage with Ludwig persisted until the beginning of the 20th century. French chroniclers of the 13th century such as Philippe Mouskes even assume Eleanor had diabolical features and justify this with the fact that one of her ancestors was in league with the devil.

Two other legends have become particularly independent over the centuries. This includes the report of an alleged adultery between Eleonore and Saladin , which Matthew Paris already suggests. In later centuries the legend of Eleanor's love affair with the famous sultan was taken up in different variations, it was only with the emergence of modern historiography in the course of the 19th century that it became known that a relationship between Eleanor and Saladin, who was born in Mesopotamia in 1138, was not historically possible is durable.

The second legend assumes that Eleanor murdered Rosamund Clifford , her husband's mistress. The story that Heinrich wanted to protect his lover with a labyrinth, but found his jealous wife Rosamund anyway and gave her the choice of dying by poison or by the dagger, was used in innumerable poems, tragedies, operas and short stories in all of Europe Languages picked up. The story has its origins in the English chronicler Ranulf Higden , who reported as early as the 14th century about a labyrinth built by Heinrich to protect Rosamund from the jealous queen. In the sixteenth century, writers such as John Stow and Samuel Daniel took up this story and further adorned it. It was not until the middle of the 19th century that individual authors no longer began to see the fury murdering with poison and dagger in Eleonore. Charles Dickens, for example, underlines in his “Child's History of England”, written between 1851 and 1853, that the end of Rosamund's life was probably much less dramatic and that she spent her last days in a monastery near Oxford.

Plays, films, novels and visual arts

Eleonore's life has been dealt with in many plays, novels, films, and television plays. For example, Eleanor is one of the characters in William Shakespeare's 1595/1596 historical drama King John . In Gaetano Donizetti 's opera Rosmonda d'Inghilterra , which was premiered in 1834 , Eleanor, known as "Leonora", is portrayed as the murderess of Heinrich's mistress. Also historically incorrect is Jean Anouilh's drama Becket or the Glory of God , in which Eleanor is one of the minor characters. The play was filmed in 1964 and shown in Germany under the title Becket .

Along with Heinrich, Eleanor was one of the two central characters in James Goldman's play The Lion in Winter, which premiered in 1966 . The play takes place around Christmas time in 1183 and addresses the intrigues surrounding Heinrich's successor. The play was filmed with the same title in 1968. The film is exceptionally well cast: Eleanor is played by Katharine Hepburn , Heinrich by Peter O'Toole , the young Richard the Lionheart by Anthony Hopkins and the French King Philippe II by Timothy Dalton . The film received a number of awards. Among other things, Katharine Hepburn was honored with an Oscar for her portrayal of Eleonore as best leading actress . The remake of the same name, starring Glenn Close and Patrick Stewart , was released as a television film in 2003 and earned Close an Emmy nomination and a Golden Globe in 2005 . Eleonore appears as a minor character in several television and cinema adaptations of the Robin Hood and Ivanhoe material. Well-known adaptations include the movie Robin Hood and his daring journeymen (1952) and the television series The Adventures of Robin Hood , Ivanhoe (both 1950s) and Robin Hood (2006-2009).

Eleanor is also the main character in a number of historical novels . Authors who have dealt with her life in this way include Eleanor Hibbert , who wrote several novels about her under the pseudonym Jean Plaidy, Tanja Kinkel ( The Lioness of Aquitaine , 1991) and Alison Weir , who after her work in her biography about Eleanor of Aquitaine also used the material in a novel ( The Captive Queen , 2010). Sabine Weigand wrote the historical novel "Ich, Eleonore, Königin Zwei Reiche", published in 2015. Pamela Kaufman wrote the historical novel "The Book of Eleanor" in 1997, the German translation was published under the title "Die Herzogin".

Eleonore also found its way into the visual arts of the 20th century. The feminist artist Judy Chicago made her role in the history of women clear: In her work The Dinner Party , she dedicated one of the 39 place settings at the table to her.

ancestors

| William VIII of Aquitaine | Hildegard of Burgundy | William IV of Toulouse | Emma de Mortain | Boson from Châtellerault | Aliénor de Thouars | Bárthelemy du Bueil | Gerberge de Blaison | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| William IX. the troubadour | Philippa of Toulouse | Aimery I of Châtellerault | Dangereuse de l'Isle Bouchard | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| William X of Aquitaine | Eleanor of Châtellerault | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eleanor of Aquitaine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Family table

|

William IX. the troubadour 1071–1127 |

Philippa of Toulouse | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

William X of Aquitaine 1099–1137 |

Eleanor of Châtellerault 1103–1130 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Louis VII. 1120–1180 |

Eleanor of Aquitaine 1120–1204 |

Heinrich II. 1133–1189 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Marie of Champagne 1145–1198 |

Alix of Blois 1150-1195 |

Wilhelm 1153-1156 |

Heinrich the Younger 1155–1183 |

Mathilde 1156-1189 |

Richard the Lionheart 1157–1199 |

Gottfried II. 1158–1186 |

Eleonore Plantagenet 1162–1214 |

Johanna 1165-1199 |

Johann Ohneland 1167-1216 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Marriages

1. ⚭ (1137, canceled 1152) King Louis VII of France

2. ⚭ (1152) Henry Plantagenet , later King Henry II of England

progeny

- (1) Marie (1145–1198) ⚭ Henry I, Count of Blois-Champagne

- (1) Alix (1150–1197 / 1198) ⚭ Theobald V. , Count of Blois and Chartres

- (2) Wilhelm (August 17, 1153–1156)

- (2) Henry the Younger (1155–1183), heir to the throne and co-king of his father, ⚭ Margaret of France , which would have actually meant a union of the two countries at the time, after all, Philipp August was not yet born

- (2) Mathilde (1156–1189) ⚭ Heinrich the Lion , Duke of Saxony and Bavaria

- (2) Richard the Lionheart (1157–1199), King of England, ⚭ Berengaria of Navarre

- (2) Gottfried II (September 23, 1158– August 19, 1186), Duke of Brittany, ⚭ Konstanze von der Bretagne , the last descendant of the Dukes of Brittany

- (2) Eleonore (1162–1214) ⚭ King Alfonso VIII of Castile

- (2) Johanna (October 1165 – September 1199) ⚭ I. 1177 King Wilhelm II of Sicily and ⚭ II. 1196 Raymond VI. , Count of Toulouse

- (2) Johann Ohneland (1167–1216), King of England, ⚭ Isabella von Angoulême , son: Heinrich III. from England

literature

- Elizabeth AR Brown: Eleanor of Aquitaine: Parent, Queen, and Duchess. In: William W. Kibler (Ed.): Eleanor of Aquitaine - Patron and Politician. University of Texas Press, Austin 1976, ISBN 0-292-72014-9 , pp. 9-34.

- Amy Ruth Kelly: Eleanor of Aquitaine and the four kings. Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1950.

- Daniela Laube: Ten chapters on the history of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Lang, Bern a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-261-03476-9 .

- Jean Markale: La vie, la légende, l'influence d'Aliénor comtesse de Poitou, Duchesse d'Aquitaine, Reine de France, puis d'Angleterre, Dame des Troubadours et des bardes Bretons. Payot, Paris 1979, ISBN 2-228-27310-4 ; Paperback edition: 1983, ISBN 2-228-13300-0 .

- Marion Meade: Eleanor of Aquitaine - a biography. Penguin books, London 1991, ISBN 0-14-015338-1 .

- Régine Pernoud : Queen of the Troubadours. Eleanor of Aquitaine. 13th edition. dtv, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-423-30042-6 .

- Ralph V. Turner: Eleanor of Aquitaine - Queen of the Middle Ages. CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-63199-3 .

- Ursula Vones-Liebenstein: Eleanor of Aquitaine. Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen 2000, ISBN 3-7881-0152-0 .

- Alison Weir: Eleanor of Aquitaine - By the wrath of God, Queen of England. Pimlico, London 2000, ISBN 0-7126-7317-2 .

Web links

- Andrea Stahl: Eleanor of Aquitaine. A controversial personality through the ages ; aventinus mediaevalia No. 11 [09/04/2010]; aventinus student publication platform history

- Literature by and about Eleanor of Aquitaine in the catalog of the German National Library

- FemBiography: Eleanor of Aquitaine

Individual evidence