Platonic love

Platonic love is a form of love that has been named after the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (428/427 BC - 348/347 BC) since the Renaissance because its philosophical foundation is based on his theory of love and because their supporters rely on him. In modern usage, however, the expression “Platonic love” has a meaning and connotations that have little or nothing to do with Plato's original concept.

Plato sees in love ( Eros ) a striving of the lover, which should always lead him from the particular to the general, from the isolated to the comprehensive. According to the Platonic theory, this happens when the lover is or becomes a philosopher and as such deals with love in a manner described by Plato. The lover in the sense of Plato consciously chooses a philosophical path that should lead him to ever higher knowledge. He directs the erotic urge in the course of a stepped cognitive process to ever more comprehensive, general, higher-ranking and therefore more rewarding objects. In the end, the most general reality attainable in this way, which Plato defines as the beautiful in itself, proves to be the most worthy object. There the lover's search ends, because only there he finds the perfect fulfillment of his striving according to this teaching.

In modern parlance, a friendship is usually referred to as "platonic" when the people friends are not sexually interested in each other. The term is also used for a potentially erotic relationship in which one voluntarily renounces sexual gratification or has to forego it due to circumstances. It is only a question of renunciation as such, not of a philosophical motivation, justification or goal setting, which often does not even exist. For example, the reason may be that the ability or opportunity to engage in sexual activity is lacking or impossible because the loved one does not consent to it.

Plato's view

Definition

There are differentiating terms in ancient Greek for the different things that are referred to in German with the term “love” : eros (the “erotic” love associated with intense desire), philia (mild, friendly love, affection) and agape (benevolent Love without the motive that the lover desires something from the beloved). In Plato's concept, insofar as it is the starting point for what will later be called “platonic” love, it is about eros. The lover feels a serious deficiency in himself. Therefore he strives intensely for something that could compensate for this lack and for this reason becomes the object of his love. He wants to attain this object, he wants to connect with it or to appropriate it. Thus, one of the main characteristics of a love that is literally “platonic” is that it is erotic, that is, that the lover desires the object of his love fiercely. This desire is the driving force behind his actions.

In his writings, Plato deals not only with eros, but also with a friendly or family love, the characteristic of which is not erotic desire, but only permanent affection. For the origin and history of the term “platonic love”, however, this topic is of little importance, because the root of the later “platonic” love is eros, in which, from the point of view of the desiring lover, there is a gap between one's own lack and that of others Abundance is possible.

Sources

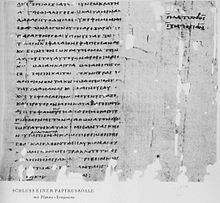

In several of his fictional, literary dialogues, Plato lets the interlocutors analyze the nature and meaning of love. The famous Dialog Symposium in particular is entirely dedicated to this topic. At a banquet ( symposium , "drinking binge") the participants hold speeches in which they present different, sometimes contradicting approaches and theories. In this way of presenting the subject, Plato deliberately refrains from presenting his own doctrine and identifying it as such. He leaves the conclusion to the reader. Nevertheless, it is largely clear from the type of presentation which views he considers to be inadequate or wrong and which arguments and conclusions he approves. In the interpretation of Plato, one traditionally assumes - also in modern research - that the considerations that Plato puts in the mouth of his teacher Socrates in the dialogues are essentially his own. Thoughts of other dialogue participants can also reflect his position. This is to be assumed or can be assumed if these utterances agree or are at least compatible with what is otherwise known about his philosophy.

With regard to love, which has been called “Platonic” since the Renaissance, the most important text is Socrates' speech in the symposium . There Socrates does not give his own knowledge, but refers to an instruction that the seer Diotima gave him in his youth. The view of Diotima, which he explains in detail, is expressly and unreservedly agreed by Plato's Socrates, and he advocates its dissemination. Therefore, the prevailing view in research today is that the essence of what Plato's concept of love can be found in Diotima's remarks. This does not mean, however, that his view is completely identical with the one she has put forward; Important and for the topic relevant components of Plato's philosophy such as the theory of ideas , the anamnesis theory and the immortality of the soul are not addressed by Diotima or only hinted at.

The assertions of Socrates' interlocutors in the symposium are for the most part incompatible with Plato's point of view and shaped by a sophistic way of thinking that is opposite to the Platonic one. Therefore they can only be used to a limited extent as sources for Plato's philosophy. The speeches of the other participants in the dialogue who spoke before Socrates are not insignificant, but an essential part of a common endeavor to gain knowledge. To what extent they also contain useful approaches from Plato's point of view is controversial in research. At least in Aristophanes' speech there are thoughts that have points of contact with the Platonic theory of love. Confirmatory and additional information on the theory of love can be found in other dialogues of Plato ( Phaidros , Politeia , Nomoi , Lysis ).

The theory of erotic love

Mythical approach

Since Plato is of the opinion that the essential cannot be adequately grasped and expressed through mere argumentation, he also uses myths to illustrate his interpretation of the phenomenon of love . In the symposium , Aristophanes tells the myth of the spherical people . According to the myth, humans originally had spherical torsos and four hands and feet and two faces on one head. In their arrogance they wanted to storm the sky. For this she punished Zeus by cutting each of them in half. These halves are today's people. They suffer from their incompleteness; everyone seeks the lost other half. The longing for the lost wholeness manifests itself in the form of erotic desire aimed at union. Some spherical people had two male halves, others two female halves, and still others had one male and one female. Depending on this original nature of the whole being, its separate halves show a heterosexual or homosexual disposition. This myth points to a core component of the Platonic theory of love, the explanation of eros as a phenomenon of deficiency. The erotic desire is interpreted as the desire to remedy a defect and to achieve wholeness or perfection.

Socrates, who will speak later, takes up the point of view of deficiency raised by Aristophanes and deepens it. He also tells a myth, referring to Diotima. The nature of human eros is explained by reference to the figure that embodies it in mythology .

According to this representation, the mythical Eros is not - as in a widespread tradition - the son of the goddess Aphrodite , but he was conceived at the feast that the gods held on the occasion of Aphrodite's birth. His mother Penia , poverty personified , came to the meal as a beggar and met the drunken Poros ("pathfinder") there. Poros is the personification of resourcefulness that always finds a way out and paves the way to abundance and wealth. However, as his drunkenness suggests, he lacks the ability to be moderate. In order to compensate for her need, Penia wanted to conceive a child from him. So it came to the procreation of Eros, which later joined the goddess, whose birth festival had led to the meeting of his parents, and became her companion. In his nature, Eros combines the qualities of his father with those of his mother. He inherited the principle of want from his mother, so he is poor and unsightly, barefoot and homeless. From his father he got his energy and cunning, his magic and the strong inclination for the beautiful and the good that drives him. Since wisdom counts for beauty, he is also a philosopher (“wisdom lover”). He lacks insight, but eagerly strives for it, being aware of this lack.

Like mythical eroticism, human eroticists also strive for the fullness they lack, for the beautiful and the good. You want to achieve what you strive for by all means and then possess it permanently in order to be happy.

In this myth, too, the lover is viewed from the point of view of his inadequacy. He suffers from his need and, as an erotic person, uses all his ingenuity to remedy it. Eros itself, the archetype of the erotic, cannot be a god, for as such he would be beautiful and blissful, not unsightly and needy. But neither is he a mortal, but a middle being, a "demon" ( daimon ) who stands between gods and humans and mediates between them. His name stands for the impulse to perfection, which drives people to higher development and thus to approach the sphere of the gods. Socrates emphasizes that Eros ennobles people and is their best helper. Therefore one should honor him and everything that belongs to eroticism and practice in this field.

Stage model of ascent

The first thing that awakens the power of eros in a young person is the sight of beautiful bodies. Since every beauty is an aspect of the divine, it is immediately attractive. Therefore, the erotic desire is initially directed towards the beautiful in the form in which it confronts the human being on the physical level in a sensually perceptible way. Wherever you meet something beautiful, eroticism can unfold.

The erotic attraction reaches a particular strength when the desired person is not only physically beautiful, but also mentally, i.e. virtuous. On this basis, as Socrates reports in the symposium , Diotima develops her doctrine of the right philosophical control of the erotic urge. In youth, one should turn to beautiful bodies and realize that it is not about the advantages of a particular body, but about the physical beauty itself, which is the same in all beautiful bodies. Later one will turn to the spiritual beauty that one initially perceives in a certain person. Therefore, love is now directed towards this person, even if it is outwardly unsightly. This leads to a focus on ethics ; the lover discovers the beautiful in beautiful actions. Later the beauty of knowledge becomes perceptible to him. In doing so, he has the opportunity to discover that in the spiritual and spiritual realm too, beauty is not tied to something individual, but is the general, which always shows itself in particular. From there the lover arrives at the highest level of knowledge. There it is no longer a matter of individual virtues or individual beautiful deeds or insights, but rather beauty in the most general and comprehensive sense: the perfect and unchangeable beauty par excellence, which is ultimately the source of all forms of beauty. This primal beauty is not a mere abstraction, not a conceptual construct, but a perceptible reality for those who have reached the last level. The breakthrough to the perception of primal beauty happens “suddenly”. Anyone who has experienced this has reached the goal of the erotic effort. He is relieved of the need that initially drove him to physical manifestations of the beautiful.

One of the main characteristics of the erotic is that he is not content with a passive contemplation of the beautiful, but strives for a creative activity to which the beautiful stimulates. He not only wants to receive impressions, but also to produce something himself. Its ability to produce, like beauty, is of a divine nature, so it unfolds where it encounters the inherently related beauty.

A universal aspect of the erotic will to generate is the instinct to reproduce, the urge to leave offspring; Eros also works in the animal kingdom. However, man has the power of procreation or fertility not only in the physical, but also in the spiritual and spiritual sense. His "descendants" are also the political and cultural works he created.

The ascent to the absolutely beautiful, driven by Eros, is a special case of Plato's general concept of ascent, which he also expounded elsewhere, especially in the allegory of the cave of Politeia . The task and goal of the ascending one are always the same, the procedure is analogous in the teaching of Diotima and in the allegory of the cave. The path of the philosopher - in the special case: the philosophizing erotic - always leads from the isolated to the comprehensive and thus from the defective to the perfect. It is about the knowledge of a reality structure that is closed to the unphilosophical person, but can be discovered through the philosophical activity of progressing step by step to higher levels of reality. The general is first grasped in detail through perception, then gradually isolated and made the object of knowledge as what it is itself, until finally the gaze can turn to the most general and comprehensive, i.e. the best of everything. In the symposium , this process is illuminated by advancing towards the perception of the primal beauty, in the Politeia by means of an analogous advancement towards the absolutely good.

Sexual problem

All love relationships that are described in Plato's dialogues are homoerotic. Such relationships were taken for granted and were discussed impartially. However, same-sex sexual execution was problematized. Plato disapproved of it on the one hand because he considered it to be contrary to nature, on the other hand because he rejected hedonism in general and considered a fixation on physical desires as wrong and unworthy of a philosopher. Therefore, sexuality does not appear in his ascent model. In the symposium he only lets the drunken Alcibiades appear after Socrates' speech , who was connected to Socrates by a strong erotic attraction on both sides. Alcibiades, to praise Socrates, describes his futile attempt to seduce his lover into sexual activity. In his portrayal, Socrates appears as an exemplary philosopher who calmly lets the efforts of Alcibiades come to nothing.

History of terms and effects

Ancient and Middle Ages

In the 3rd century Plotinus , the founder of Neoplatonism , wrote a treatise On Eros in which he allegorically interpreted Plato's myth of Eros from the symposium . He regarded Eros as belonging to the world soul and thus classified it in the system of the Neoplatonic model of the world order, the doctrine of hypostasis . He distinguished between two types of erotic love. One only strives for familiarity with the primal beauty that it wants to look at, so it is not productive; the other wants, as Plato described it, to beget or produce in the beautiful. Plotinus considered both types to be legitimate and worthy of praise, but the purely contemplative was more important to him. He understood the experience of transcendent beauty as a self-experience of the soul, which looks at itself. In doing so, through her erotic striving, she not only arrives at the beautiful in itself, but also at the absolutely good , that is: on the one hand , the highest principle. Plotin's Eros seeks and finds fulfillment not through the attainment of an external object, but in the retreat of the individual to himself, where he can encounter the divine within himself. All external love objects do not awaken love through their own being, but only because and to the extent that they depict the absolute good. This is thus the only true object of erotic striving. According to its nature, the soul can have direct access to this object, since it is inherent in itself.

The late antique Neo-Platonist Proklos represented a somewhat different concept . For him, the ascent driven by eros leads to the beautiful itself, the ultimate goal of eros, but not to the one. On the one hand, one can only get through pístis (certainty) after eros has achieved its goal and remedied its imperfection and has thereby come to rest.

In ancient Judaism, the Platonic concept of Eros found little resonance. In the Septuagint , the Greek translation of the Tanakh , only two passages speak of an “erotic” love, which is comparable to the Platonic Eros; it is a love of wisdom. An exception was the Jewish Platonist Philo of Alexandria , who used the term Eros in a positive sense corresponding to the Platonic understanding.

Influential Christian writers, whose authority from late antiquity set the trend for Western philosophy and theology, took over considerable parts of the Platonic ideas in a modified form, including the concept of the erotic ascent. They equated the highest goal of the Platonic erotic with God in the sense of the Christian concept of God. From their point of view, this resulted from the assumption that God as “the good” is the epitome of everything worth striving for.

In the third century, the church writer Origen , who was strongly influenced by Platonism, took the view in the prologue of his commentary on the Song of Songs that it was legitimate to describe the love affair between God and man in erotic terms. He thus initiated the later common mixing of the conventional, philosophical discourse and the New Testament concept of love.

The church father Methodios of Olympos , who lived in the late 3rd century, wrote dialogues, including a symposium in Plato's style. His symposium , in which he glorifies virginity as an expression of Christian eros, contains numerous allusions to the works of Plato, in particular his dialogue of the same name, from which he also took verbatim quotations. In Methodios, virginity ( chastity ) takes on the role that Eros plays in Plato. Like this, it is an active principle, not mere renunciation, and is intended to lead the striving man to a vision of beauty that is equated with God. Methodios depicts this show based on the example of Plato's Diotima speech and a passage in his dialogue Phaedrus . In his opinion, however, it is only possible in a perfect way in the hereafter.

In late antiquity, the influential theologian Augustine († 430) took up the Platonic concept of the lover's ascent to the most worthy object of love and used it for his own purposes. In it he found a philosophical support for the value system of the Christian doctrine of love, in which love of neighbor is above erotic love for a certain person and love of God above all other forms of love. As with Plato and Plotinus, with Augustine the human urge to love aims at the perfection of the longing lover who is aware of his inadequacy. The one striving for love fulfillment reaches his goal and thus happiness when he has found the highest possible love object in God.

Other well-known ancient church fathers also represented a concept of love that was shaped by Platonic ideas. Eastern, Greek-speaking authors in particular, and later Byzantine theologians, based their interpretation of the biblical commandment on love on the Platonic tradition. This had a strong effect in the Orthodox churches , especially with regard to the theological appreciation of love for a platonic beauty. The influential late antique church writer Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita emphasized the unity of the good and the beautiful and considered love for God and love for beauty to be inseparable. In the sense of the Platonic tradition, he used the word eros for all love with a transcendence reference, even if he meant love in the New Testament sense, which is usually called agape , and justified this use of the word. He referred to the opinion of some theologians that the name eros is even more divine than the name agape . For him, Eros was the unified, unifying and unifying power that links the higher and the lower, the lower strive for the higher and at the same time allows the higher to take care of the lower. In doing so, he changed Plato's concept, in which the work of eros is attributed exclusively to the defects of the lovers. The concept of a special “platonic” form of love did not exist then or in the Middle Ages.

Revival in the 15th century

During the Renaissance, Plato's previously largely lost works, including the symposium , were rediscovered. An early defender of Platonic Eros was Leonardo Bruni († 1444), who, with reference to Plato's dialogue Phaedrus, claimed that only a “madly” lover in the sense of the concept presented there, who is alienated and forgetting himself to a certain extent, can God completely love. Humanistic thinkers, especially Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) and Cardinal Bessarion (1403–1472), endeavored to harmonize the now widely known Platonism and the Christian faith.

This reception of Plato met with opposition from the Greek Aristotelian Georg von Trebizond , who lived in Italy and who published a comparative study of the teachings of Plato and Aristotle in 1455. With sharp polemics George fought the influence of Plato, which he considered to be even more pernicious than Epicurus . He also pointed out the homoerotic aspect of the Platonic doctrine of love, which is unacceptable for Christians.

Marsilio Ficino translated Plato's dialogues into Latin ; he also commented on some, including the symposium . In doing so, he gave them a broad impact. His intention to demonstrate the truthfulness of Plato's doctrine and at the same time a harmony between Platonism and Christianity was particularly directed at the theory of love. In his interpretation of Plato's texts he was strongly influenced by Plotin's point of view.

Like Plato, Ficino defines love as the pursuit of beauty, which he defines as the “splendor of divine goodness”, and emphasizes its creative function, since it is it that gives shape to the formless and chaotic. He believes that beauty is inseparable from goodness; Beauty is external perfection and goodness is internal. The intensity of the beauty corresponds to the degree of the goodness and thus shows it reliably. For humans, the quality of an object can only be recognized by the fact that the sensually perceptible characteristics of beauty lead to it. For Ficino, however, these characteristics are nothing physical. He emphasizes the purely spiritual nature of beauty, in which he sees a structure that permeates and shapes the material.

According to Ficino's teaching, all love begins with sight. It can then rise contemplatively to the purely spiritual, or turn to the physical with pleasure, or remain in the perception. This results in three basic ways of shaping life, between which people can choose.

Ficino coined the term “platonic love”. He only used it in one letter, however; his symposium comment only speaks of “Socratic love”. By Socratic love he understands love among friends in its highest possible form, as embodied by Socrates as the exemplary lover. Socrates appears as the loving educator who erotically binds the youth to himself in order to initiate them into philosophy and to inspire them for true values. In the sense of the Platonic tradition, such love is not limited to the relationship between people, but rather directs the lovers towards a transcendent goal. For Ficino this is God as the absolute good and the source of the beautiful.

According to Ficino's teaching, the orientation towards this goal is a return of the human soul to that which is divine in it. The loving soul turns back on itself in order to be able to turn to God thanks to the divine light present in it. Platonic eros and Christian doctrine of love come together. In modern Christian Platonism, the Platonic eros theory merges with the Christian doctrine of agape (this term in the Greek Bible denotes both love for God and God's love and neighborly love).

However, this mixing blurred the contours of the specifically Platonic element. A linguistic factor promoted this development. In Latin, the learned and educated language of the early modern period , there is no special word for desiring love in the sense of the Greek eros . Therefore the erotic, desiring character of the love meant by Plato was blurred by the translation into Latin. Ficino also used the Latin words amor (love in general) and caritas (love in the sense of agape ) indiscriminately, as if they were synonyms . This fact contributed to the fact that the concept of love, now labeled as “platonic”, moved away from its ancient origins.

Persistence of the platonic concept in the early modern period

Elements of Plato's love discourse found their way into numerous literary works of the Renaissance and the 17th century, partly in a direct way, partly via Ficino's interpretation. Some of the authors who were inspired by this include Baldassare Castiglione ( Il libro del Cortegiano ) , Pietro Bembo (Gli Asolani) and Leone Ebreo (Dialoghi d'amore) ; like Plato, they discussed questions of love in dialogue form. The poet Girolamo Benivieni († 1542) put the main ideas of Ficino's symposium commentary in verse. Queen Margaret of Navarre († 1549), who worked as a writer, incorporated a lot of platonic ideas into her concept of love. She could read Plato's dialogues in their original text. Later in France, well-known novelists ( Honoré d'Urfé , Madeleine de Scudéry , Fénelon ) received elements of the Platonic Eros concept. A number of poets ( La Pléiade , Lyoneser poet school ) used individual thoughts of Plato on Eros in their works. In contrast to the diverse literary echo, there was only a minimal discussion of the topic at the universities.

In 1531 the philosopher Agostino Nifo published a detailed critique of the Platonic doctrine of love from an Aristotelian point of view. In particular, he rejected the connection of sensual love, which he valued positively, to a metaphysical origin.

In England in the 17th century, the Cambridge Platonists , who represented Christian Platonism, received the symposium in the sense of Ficino's way of thinking. Henry More particularly attached importance to the teaching of eros. The English philosopher Shaftesbury (1671–1713) tied in with this group of Platonists, who reaffirmed the Platonic idea of an eros aiming at beauty and therefore necessarily at truth. Shaftesbury's work, which puts the aesthetic dimension of Platonism in the foreground, received a lot of attention not only in his home country, but also in France and Germany.

Friedrich Hölderlin's work was strongly influenced by the Platonic theory of love. The thought that Eros can lift the lover above the ephemeral individual is poetically expressed in the ode The Farewell and in the elegy Menon's lamentations about Diotima . In his epistolary novel Hyperion , on which he worked in the last years of the 18th century, he brought the Eros concept of Plato's symposium to bear.

Christoph Martin Wieland made a fundamental criticism of Plato's theory of eros in his epistolary novel Aristippus (1800/1801). A letter there reports on a banquet at which the participants in the discussion came to results that radically contradict Plato's approach. Against the doctrine of the primordial beauty as the highest goal of eros, it was objected that the primeval beauty lies outside the realm of possible human experience. Therefore it cannot be the goal of love.

Reception of the Platonic Concept in Modernity

Philosophy and Classical Studies

Ludwig Klages brought strong criticism in his work Vom kosmogonischen Eros , first published in 1922 . Klages characterized Plato's concept of love as "life-negating" and unrealistic. In reality, a person is always loved as an individual and never for the sake of their praiseworthy qualities. For the lover, it is not about advantages that the loved one shares with other people, but about the totality of those peculiarities that distinguish this individual from all other conceivable beings and make it incomparable. This is even the case if the lover perceives these peculiarities as weaknesses and defects. Therefore, the loved one cannot be replaced by another one who has more or more pronounced advantages. Contrary to Plato's view, eros has nothing to do with need and want, but shows itself as the urge to overflow and to pour out. Plato tries to divert this urge to “conceptual ghosts”, but thereby suppressing and destroying real Eros. This is an illegitimate and disastrous interference of the mind in matters of the soul.

In the research of antiquity, besides the question of which statements of the dialogue participants of the symposium correspond to Plato's own position, above all the peculiarity of his love theory was discussed. It is about the delimitation of a specifically Platonic Eros from other phenomena designated by the term “love” and the question of whether Platonic Eros is ultimately a matter of self-love. Philosophers and theologians have also expressed their views on this, whose concern is to distinguish between the Greek (especially Platonic) and the Christian understanding of love.

Max Scheler took a position in his book Love and Knowledge, first published in 1915 . When interpreting the relationship between love and knowledge, he distinguishes between two basic concepts, an “Indian-Greek type” and the Christian approach that is radically opposed to this. The Indian and the ancient non-Christian approaches (especially Plato and Aristotle) have in common that the priority of knowledge is assumed. According to these positions, it must be preceded by the knowledge that love is its fruit. The movement of love is therefore dependent on the progress of knowledge. In this way love is determined intellectualistically. Since Plato regards love as a striving from imperfect to perfect knowledge, for him a perfect deity can only be an object of love, but not love itself. As soon as the knowledge is complete, the love so conceived must disappear. This approach is wrong. In reality, love is not a striving, but rests “entirely in the being and being of its object”.

The philosopher and theologian Heinrich Scholz also dealt with the distinction between Platonic and Christian love in his treatise Eros und Caritas , published in 1929 . He, too, emphasized the fundamental impossibility of a God loving in the sense of the Platonic Eros concept. In Christianity, on the other hand, the love that proceeds from God is even a prerequisite for every love for God and also for every love between people.

In an influential study in 1930, Anders Nygren expressed the opinion that the Platonic Eros aims at the well-being ( eudaimonia , bliss) of the lover and that this exhausts its meaning. This is the case with all love concepts of the non-Christian ancient philosophers. This is a fundamental difference to Christian love of neighbor and love of God , which are oriented towards their object and not towards the well-being of the loving subject. Gregory Vlastos represented a differentiated version of this hypothesis in an essay first published in 1973. He denied Nygren's assertion that in antiquity there was an "unselfish" love for the love object's sake only in Christianity. On the other hand, he agreed that it was indeed a feature of the Platonic concept that the beloved individual was not valued for his own sake, but only because and to the extent that he embodied something general such as beauty or a virtue. It is only relevant as a carrier of certain properties. In the course of the ascent to higher, more general forms of love, the individual becomes superfluous and clinging to him is therefore absurd.

The positions of Nygren and Vlastos are abbreviated with the catchphrase of the " egocentric " character of the Platonic Eros. The egocentrism hypothesis is controversial in research and is predominantly rejected today in its radical variant. The opposite view is that Plato's idea is not so one-sided and limited, but that the virtuous individual is valued by him as a legitimate object of love. The ascent to more comprehensive levels of love need not be connected with the extinction of love for the individual, but this is only viewed and classified differently. According to an alternative hypothesis, Platonic eros is self-centered on the lower levels, but that changes as the ascension progresses.

psychology

Sigmund Freud was convinced that there are not several types of love that differ in their origin and nature, but that love is something uniform. All of its forms, including Platonic Eros, have a common root, the libido . Therefore, it is legitimate to use the term “love” for all manifestations of libido, according to the general usage, which is justified in terms of content. In defending his unity hypothesis, Freud referred to Plato, whose doctrine already contained the facts in principle: [...] so all who look down contemptuously from their higher point of view on psychoanalysis may be reminded how close the expanded sexuality is to psychoanalysis meets the eros of the divine Plato ; The "Eros" of the philosopher Plato shows in its origin, performance and relationship to sexual love a perfect correspondence with the power of love, the libido of psychoanalysis. Proponents of psychoanalysis (Max Nachmansohn, Oskar Pfister) tried to show a correspondence between Freud's concept of love and that of Plato. However, Freud saw the common root of all forms of love in the sex drive and believed that the sexual impulse remains intact in the unconscious, even if the drive has been redirected to another goal due to a lack of opportunity for direct satisfaction, as in "platonic" love. Thus the starting point of Freud's interpretation of love is the opposite of Plato's metaphysical approach.

Freud suspected a general regressive character of the instincts; he tried to reduce all urges to a need to restore an earlier state. In his presentation of this hypothesis, he cited, among other things, the myth of the sphere man in the symposium . There Plato expressed the facts in mythical language.

Hans Kelsen undertook a psychological interpretation of Plato's theory of eros in the essay Die Platonische Liebe , published in 1933 . He interpreted Plato's philosophical confrontation with eroticism as the result of an unsolved personal problem of the philosopher, which had played a central and fatal role in his life. The sexual component of the Platonic Eros presents itself as an essential part, as the ultimate foundation, as the breeding ground, as it were, from which the spiritualized Eros grows . In contrast to many bisexual contemporaries, Plato was purely homosexual. This orientation had met with widespread disapproval in Athens because it was seen as a threat to the continued existence of society. As a homosexual, Plato got into a serious internal conflict between instinct and social norm, which prompted him to justify his sexual orientation through metaphysical transfiguration. In particular, the fact that he did not start a family and thus neglected a civic duty had to be justified. His personal problem also had an impact on his political attitude; his basic anti-democratic attitude can be interpreted as a necessary consequence of his homosexuality.

Fundamental change in the meaning of the term "platonic love"

In the course of time there was a fundamental change in meaning, which eventually led to a modern use of the term that bears only a slight resemblance to Plato's concept.

Plato had not rejected the erotic love of the body, but regarded it as an inadequate, but necessary and sensible, initial stage of a higher development to be striven for. According to his teaching, eros is a unified phenomenon; the erotic urge only changes its object each time it reaches a new level. Therefore, in the symposium , Plato's Socrates describes "the erotic" as worthy of reverence without reservation. Thus, no level of eroticism can be described as non-Platonic in and of itself. Ficino followed this approach. Although he distinguished love (amor) from lust (voluptas) aimed at physical satisfaction , he considered love, inflamed by physical beauty, to be a legitimate expression of platonic eros. Sensually perceptible beauty is conveyed through the eyes and ears. The three other senses, on the other hand, are unable to grasp beauty and therefore do not serve love, but rather lead it away from it.

In broad circles of the early modern age and also of the modern age, especially in the church environment, however, the love of physical beauty was judged much less favorably. It was about the possible sexual implications and in particular about the homoerotic expression clearly emerging in Plato's writings, which was very offensive to many readers. Therefore, the reception of the Platonic concept in large parts of the public was associated with a reservation: The initial stage of Plato's stage model was suspect, it was evaluated negatively and separated from the other stages or tacitly ignored.

In view of this problem, platonic love theorists used to emphasize their distance from the sexual aspects of love of beauty. This initiated the development that ultimately led to the fact that, in common parlance, Plato's theory of love was reduced to a contrast between sexual and asexual relationships and “platonic” was given the meaning “without sexuality”. Starting points for this were the passages in Plato's dialogues where a body-related desire is rejected or the reader is shown the exemplary self-control of Socrates.

In the 18th century, in the age of sensitivity, a new, intensive but one-sided reception of the Platonic concept began. Characteristic for many theories of love of this time and the early 19th century was a sharp theoretical demarcation between a sensual love that was reducible to physical needs and the purely spiritual and spiritual love that was used to call "platonic" and considered the only true love. Frans Hemsterhuis (1721–1790) was an influential representative of this point of view . Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi and Jean Paul thought similarly to him . Jean Paul's attitude, however, was ambiguous; As a satirist, he also articulated sharp criticism of the “platonic” love ideal of sensitivity.

In the 19th century, proponents of “platonic love” (in the modern sense of the term) thought along conventional lines; they did not emit any new philosophical impulses. As a result of the focus on purely spiritual and spiritual love between two people, only a part of Plato's step model was in view. The reception of Plato's theory of erosion in the general public narrowed to him.

In common parlance since the late 18th century, the term “platonic love” has been used to describe an emotional bond with a person of the opposite sex without sexual contact. Often the term is used in an ironic and derogatory sense; It is assumed that a “platonic” lover is only forced to forego sexual satisfaction. The contrast to Plato's concept of Eros is so sharp that French scholars often speak of amour platonicien when referring to Plato's concept to distinguish it from amour platonique ("Platonic love" in the modern sense).

The writer Robert Musil depicts a meaningless echo of modern ideas of “platonic love” in his novel The Man Without Qualities . There, the hostess of a salon is given the name Diotima by an admirer. With this, Musil alludes ironically to Plato's symposium . He describes a presumptuous exaggeration of trivial relationships, a verbal connection to a misunderstood traditional ideal without reference to current reality.

Scientific criticism of the modern use of terms

From the point of view of philosophical historians and classical scholars, the modern use of the term is problematic. It is denounced as questionable and misleading because it gives the wrong impression of what Plato meant and wanted. As early as 1919, the influential archaeologist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff lamented the modern misunderstanding of Plato's concerns with drastic words: What a grimace has "Platonic" love been made, and "Platonic" has the meaning of what only does so as if it were something, assumed […]. Olof Gigon is one of the scholars who later expressed himself in this sense . He found that modern backstairs psychology had extracted the well-known and infamous term of “platonic love” from the “symposium” . This is the full property of the residents of the back stairs .

literature

Plato's concept

- Christoph Horn (Ed.): Plato: Symposion. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-05-004345-6 (collection of articles)

- Anthony W. Price: Love and Friendship in Plato and Aristotle. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-19-824899-7

- Frisbee CC Sheffield: Plato's Symposium: The Ethics of Desire. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-928677-9

- Kurt Sier : The speech of Diotima. Investigations on the Platonic Symposium. Teubner, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-519-07635-7

Aftermath

- Sabrina Ebbersmeyer: Sensuality and reason. Studies on the reception and transformation of Plato's love theory in the Renaissance. Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7705-3604-5

- Vanessa Kayling: The Reception and Modification of the Platonic Concept of Eros in French Literature of the 16th and 17th Centuries with Special Consideration of the Ancient and Italian Tradition. Romanistischer Verlag, Bonn 2010, ISBN 978-3-86143-190-9

- Jochen Schmidt : History of impact. In: Ute Schmidt-Berger (Ed.): Plato: Das Trinkgelage. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-458-32381-3 , pp. 160-187

- Achim Wurm: Platonicus amor. Readings of love in Plato, Plotinus and Ficino. De Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020425-4

- Maria-Christine Leitgeb: Concordia mundi. Plato's Symposium and Marsilio Ficino's Philosophy of Love. Holzhausen / Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-85493-171-3

Remarks

- ↑ See the examples in Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm : German Dictionary , Vol. 7, Leipzig 1889, Sp. 1900 f .; Duden. The large dictionary of the German language in ten volumes , 3rd edition, Vol. 7, Mannheim 1999, p. 2942; Ruth Klappenbach, Wolfgang Steinitz : Dictionary of contemporary German , vol. 4, Berlin 1975, p. 2810.

- ↑ Kurt Sier: Die Rede der Diotima , Stuttgart 1997, p. X f .; Michael Erler : Platon (= Hellmut Flashar (Hrsg.): Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 2/2), Basel 2007, pp. 196, 372.

- ↑ See the articles in the anthology Gerald A. Press (Ed.): Who Speaks for Plato? Studies in Platonic Anonymity , Lanham 2000 and the overview by Michael Erler: Platon (= Hellmut Flashar (Hrsg.): Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 2/2), Basel 2007, pp. 75–78 .

- ^ Plato, Symposium 201d-212c.

- ^ Plato, Symposium 212a – b.

- ↑ On the question of the extent to which Diotima reflects Plato's own position, and on the lack of important parts of his teaching, see Steffen Graefe: The split Eros - Plato's drive to “wisdom” , Frankfurt am Main 1989, pp. 110–119; Kurt Sier: Die Rede der Diotima , Stuttgart 1997, p. 96, 147–197; Achim Wurm: Platonicus amor , Berlin 2008, pp. 16–22; Gary Alan Scott, William A. Welton: Eros as Messenger in Diotima's Teaching . In: Gerald A. Press (Ed.): Who Speaks for Plato? Studies in Platonic Anonymity , Lanham 2000, pp. 147-159; Christos Evangeliou: Eros and Immortality in the Symposium of Plato. In: Diotima 13, 1985, pp. 200-211.

- ↑ See also Frisbee CC Sheffield: Plato's Symposium: The Ethics of Desire , Oxford 2006, pp. 27–39; Steffen Graefe: The split eros - Plato's drive to "wisdom" , Frankfurt am Main 1989, pp. 106–110.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon (= Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 2/2), Basel 2007, pp. 197, 372-375; see. Pp. 157-162; Steffen Graefe: The split eros - Plato's drive to "wisdom" , Frankfurt am Main 1989, pp. 31–85; Anthony W. Price: Love and Friendship in Plato and Aristotle , Oxford 1989, pp. 1-14, 55-102.

- ↑ Plato, Symposium 189d-193d.

- ↑ Mário Jorge de Carvalho offers a detailed investigation: The Aristophanesrede in Plato's Symposium. The Constitution of the Self , Würzburg 2009.

- ^ Plato, Symposium 201d – 212c (Myth: 203a – 204b).

- ↑ For the character of Poros and the etymology of his name, see Steffen Graefe: The split Eros - Plato's drive for “wisdom” , Frankfurt am Main 1989, pp. 131–170.

- ↑ a b Plato, Symposium 212b.

- ↑ Plato, Symposium 210e.

- ↑ See also Stefan Büttner: The theory of literature in Plato and their anthropological justification , Tübingen 2000, pp. 215-224.

- ↑ For the correspondence between Diotima's ascent model and that of the allegory of the cave, see Kurt Sier: Die Rede der Diotima , Stuttgart 1997, pp. 151–153; Hans Joachim Krämer : Arete in Plato and Aristoteles , Heidelberg 1959, pp. 497-499.

- ↑ Plato, Symposium 213b-d, 216d-219E, 222a-c.

- ↑ On Plotin's understanding of Eros see Christian Tornau : Eros versus Agape? In: Philosophisches Jahrbuch 112, 2005, pp. 271–291, here: 273–281; Christian Tornau: Eros and the good in Plotinus and Proclus . In: Matthias Perkams, Rosa Maria Piccione (Ed.): Proklos. Method, Seelenlehre, Metaphysik , Leiden 2006, pp. 201–229, here: 202–206; Kurt Sier: The speech of Diotima , Stuttgart 1997, p. 57 f.

- ↑ Christian Tornau: Eros and the good in Plotinus and Proclus . In: Matthias Perkams, Rosa Maria Piccione (Ed.): Proklos. Method, Seelenlehre, Metaphysik , Leiden 2006, pp. 201–229, here: 203 f., 206–228. Cf. Werner Beierwaltes : Proklos. Grundzüge seine Metaphysik , 2nd edition, Frankfurt am Main 1979, pp. 306-313 (partly overtaken by Tornau's results).

- ↑ Proverbs 4: 6 and Wisdom of Solomon 8: 2.

- ↑ Isaak Heinemann : Philon's Greek and Jewish Education , 2nd edition, Hildesheim 1973, p. 286 f.

- ↑ Catherine Osborne: Eros Unveiled. Plato and the God of Love , Oxford 1994, pp. 52-54, 70-77.

- ↑ See also Katharina Bracht: Perfection and Perfection. On the anthropology of Methodius von Olympus , Tübingen 1999, pp. 195–206, especially pp. 196, 202 f .; Selene M. Benedetta Zorzi: Desiderio della bellezza , Rome 2007, pp. 337-371.

- ↑ Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita, De divinis nominibus 4.11 f. See John M. Rist: A Note on Eros and Agape in Pseudo-Dionysius . In: Vigiliae Christianae 20, 1966, pp. 235-243; Werner Beierwaltes: Platonism in Christianity , Frankfurt am Main 1998, pp. 72–75; Jan A. Aertsen: "Eros" and "Agape". Dionysius Areopagita and Thomas Aquinas on the double figure of love . In: Edith Düsing , Hans-Dieter Klein (eds.): Geist, Eros and Agape , Würzburg 2009, pp. 191–203, here: 193–196.

- ↑ Melanie Bender: The Dawn of the Invisible , Münster 2010, pp. 148–153.

- ↑ James Hankins: Plato in the Italian Renaissance , 3rd edition, Leiden 1994, pp. 70-72; see. Sabrina Ebbersmeyer: Sinnlichkeit und Vernunft , Munich 2002, pp. 58–62.

- ↑ On Bessarion see Sabrina Ebbersmeyer: Sinnlichkeit und Vernunft , Munich 2002, pp. 64–68.

- ↑ On Georg's position see James Hankins: Plato in the Italian Renaissance , 3rd edition, Leiden 1994, p. 239 f.

- ^ Marsilio Ficino, De amore 1,4.

- ^ Marsilio Ficino, De amore 2,3.

- ^ Maria-Christine Leitgeb: Concordia mundi. Plato's Symposium and Marsilio Ficino's Philosophy of Love , Vienna 2010, pp. 15–21.

- ↑ On Ficino's aesthetics see Maria-Christine Leitgeb: Concordia mundi. Plato's Symposium and Marsilio Ficino's Philosophy of Love , Vienna 2010, pp. 99–109, 112 f.

- ↑ Thomas Leinkauf: Love as a universal principle. To deal with Plato's Symposium in Renaissance Thought: Marsilio Ficino and an outlook on the love treatises of the 16th century . In: Edith Düsing, Hans-Dieter Klein (eds.): Geist, Eros and Agape , Würzburg 2009, pp. 205–227, here: 218–221.

- ↑ Marsilio Ficino, De amore 7.16. See Achim Wurm: Platonicus amor , Berlin 2008, p. 1 and note 2.

- ^ Maria-Christine Leitgeb: Concordia mundi. Plato's Symposium and Marsilio Ficino's Philosophy of Love , Vienna 2010, p. 191 f.

- ↑ Marsilio Ficino, De amore 4, 4–5.

- ^ Helmut Kuhn , Karl-Heinz Nusser: Love, I. – III. In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Vol. 5, Basel 1980, pp. 290–318, here: 303; see. David Konstan : Eros. I. About the concept. II. Eros and Cupid . In: Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart , 4th edition, Volume 2, Tübingen 1999, Sp. 1465–1467.

- ↑ For details see Vanessa Kayling: The Reception and Modification of the Platonic Concept of Eros in French Literature of the 16th and 17th Centuries with Special Consideration of the Ancient and Italian Tradition , Bonn 2010; Thomas Leinkauf: love as a universal principle. To deal with Plato's Symposium in Renaissance Thought: Marsilio Ficino and an outlook on the love treatises of the 16th century . In: Edith Düsing, Hans-Dieter Klein (eds.): Geist, Eros and Agape , Würzburg 2009, pp. 205–227, here: 223–227; František Novotný: The Posthumous Life of Plato , Den Haag 1977, pp. 438-443.

- ↑ Sabrina Ebbersmeyer: sensibility and reason , Munich 2002, p 14 f.

- ↑ See Sabrina Ebbersmeyer: Sinnlichkeit und Vernunft , Munich 2002, pp. 170–178.

- ↑ Jochen Schmidt: History of impact . In: Ute Schmidt-Berger (Ed.): Platon: Das Trinkgelage , Frankfurt am Main 1985, pp. 160–187, here: 184–186.

- ^ Klaus Manger: Lais' Antisymposion in Wieland's Aristippus . In: Stefan Matuschek (ed.): Where the philosophical conversation turns completely into poetry. Plato's Symposium and its Effect in the Renaissance, Romanticism and Modern Age , Heidelberg 2002, pp. 49–61.

- ↑ Ludwig Klages: Vom kosmogonischen Eros , 4th edition, Jena 1941, pp. 41–49, 56–59, 93 f.

- ^ Max Scheler: Writings on Sociology and Weltanschauungslehre (= Collected Works Vol. 6), 2nd edition, Bern 1963, pp. 77–98, here: 83 f.

- ↑ Heinrich Scholz: Eros and Caritas , Halle (Saale) 1929, pp. 56–61, 65–67.

- ↑ Anders Nygren: Eros and Agape. Shape changes of Christian love , 2 parts, Gütersloh 1930–1937 (translation of a study published in Swedish in 1930), especially part 1 p. 157 f.

- ^ Gregory Vlastos: The Individual as an Object of Love in Plato . In: Gregory Vlastos: Platonic Studies , 2nd edition, Princeton 1981, pp. 3-42, 424 f. (Reprint of Princeton 1973 edition with corrections).

- ↑ Support for the egocentrism hypothesis expressed u. a. Willem J. Verdenius: The concept of mania in Plato's Phaedrus . In: Archive for the history of philosophy 44, 1962, pp. 132–150, here: 139–143; Gerasimos Santas : Plato and Freud. Two Theories of Love , Oxford 1988, pp. 31 f., 52; Louis A. Kosman: Platonic love . In: William Henry Werkmeister (ed.): Facets of Plato's Philosophy , Assen 1976, pp. 53-69.

- ↑ In this sense, u. a. Arthur Hilary Armstrong: Plotinian and Christian Studies , London 1979, Articles IX and X; Donald Levy: The Definition of Love in Plato's Symposium . In: Journal of the History of Ideas 40, 1979, pp. 285-291 and Catherine Osborne: Eros Unveiled. Plato and the God of Love , Oxford 1994, pp. 54-61, 222-226; Anthony W. Price: Love and Friendship in Plato and Aristotle , Oxford 1989, pp. 45-54, 97-102; C. David C. Reeve: Plato on Eros and Friendship . In: Hugh H. Benson (ed.): A Companion to Plato , Malden 2006, pp. 294–307, here: 300–302; Frisbee CC Sheffield: Plato's Symposium: The Ethics of Desire , Oxford 2006, pp. 154-182. See Martha C. Nussbaum : The fragility of goodness , Cambridge 1986, pp. 166-184.

- ↑ This opinion u. a. John M. Rist: Eros and Psyche , Toronto 1964, pp. 33-40 and Timothy A. Mahoney: Is Socratic eros in the Symposium Egoistic? In: Apeiron 29, 1996, pp. 1-18. Mahoney provides an overview of the older literature on pp. 1-3 and note 4-6.

- ^ Sigmund Freud: mass psychology and ego analysis . In: Sigmund Freud: Gesammelte Werke , 5th edition, Vol. 13, Frankfurt am Main 1967, pp. 71–161, here: 98–100.

- ↑ Sigmund Freud: Three treatises on the theory of sex . In: Sigmund Freud: Gesammelte Werke , 5th edition, vol. 5, Frankfurt am Main 1972, pp. 27–145, here: 32; see. Freud's essay Resistance to Psychoanalysis . In: Gesammelte Werke , 5th edition, vol. 14, Frankfurt am Main 1972, pp. 97–110, here: 105.

- ^ Sigmund Freud: mass psychology and ego analysis . In: Sigmund Freud: Gesammelte Werke , 5th edition, Vol. 13, Frankfurt am Main 1967, pp. 71–161, here: 99.

- ^ Anthony W. Price: Plato and Freud . In: Christopher Gill (Ed.): The Person and the Human Mind , Oxford 1990, pp. 247-270, here: 248, 250-258, 269 f. See also the comparison of the two approaches in Gerasimos Santas: Plato and Freud. Two Theories of Love , Oxford 1988, pp. 116-119, 153-184.

- ↑ Sigmund Freud: Beyond the pleasure principle . In: Sigmund Freud: Gesammelte Werke , 5th edition, vol. 13, Frankfurt am Main 1967, pp. 1–69, here: 62 f. Cf. Gerasimos Santas: Plato and Freud. Two Theories of Love , Oxford 1988, p. 161 f.

- ↑ Hans Kelsen: Essays on Ideology Criticism , Neuwied 1964, pp. 114–197, here: 134.

- ↑ Hans Kelsen: Essays on the critique of ideology , Neuwied 1964, pp. 114–197, here: 153–157.

- ↑ Hans Kelsen: Essays on Ideology Criticism , Neuwied 1964, pp. 114–197, here: 119 f.

- ^ Maria-Christine Leitgeb: Concordia mundi. Plato's Symposium and Marsilio Ficino's Philosophy of Love , Vienna 2010, p. 22 f .; Sabrina Ebbersmeyer: Sinnlichkeit und Vernunft , Munich 2002, pp. 73–78. On the problem of the sexual aspect of this eroticism in Ficino see Wouter J. Hanegraaff : Under the Mantle of Love: The Mystical Eroticisms of Marsilio Ficino and Giordano Bruno . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Jeffrey J. Kripal (Eds.): Hidden Intercourse. Eros and Sexuality in the History of Western Esotericism , Leiden 2008, pp. 175–207, here: 178–194.

- ↑ Jill Kraye: The transformation of Platonic love in the Italian Renaissance . In: Anna Baldwin, Sarah Hutton (eds.): Platonism and the English Imagination , Cambridge 1994, pp. 76–85, here: 76 f .; Diskin Clay: The Hangover of Plato's Symposium in the Italian Renaissance from Bruni (1435) to Castiglione (1528) . In: James H. Lesher et al. a. (Ed.): Plato's Symposium. Issues in Interpretation and Reception , Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2006, pp. 341–359, here: 344 f .; Sabrina Ebbersmeyer: Sinnlichkeit und Vernunft , Munich 2002, pp. 58, 63 f., 71, 131-133; Lloyd P. Gerson: A Platonic Reading of Plato's Symposium . In: James H. Lesher et al. a. (Ed.): Plato's Symposium. Issues in Interpretation and Reception , Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2006, pp. 47-67, here: 47; Gerhard Krüger : Insight and Passion , 5th edition, Frankfurt am Main 1983, p. 3 f.

- ↑ John Charles Nelson: Renaissance Theory of Love , New York 1958, pp. 69-72; Sabrina Ebbersmeyer: Sinnlichkeit und Vernunft , Munich 2002, pp. 65 f., 69–71; Unn Irene Aasdalen: The First Pico-Ficino Controversy . In: Stephen Clucas u. a. (Ed.): Laus Platonici Philosophi. Marsilio Ficino and his Influence , Leiden 2011, pp. 67-88, here: 79-83; Jill Kraye: The transformation of Platonic love in the Italian Renaissance . In: Anna Baldwin, Sarah Hutton (eds.): Platonism and the English Imagination , Cambridge 1994, pp. 76-85, here: 77-81.

- ↑ Maximilian Bergengruen : From the beautiful soul to the good state . In: Stefan Matuschek (ed.): Where the philosophical conversation turns completely into poetry. Plato's Symposium and its Effect in the Renaissance, Romanticism and Modern Age , Heidelberg 2002, pp. 175–190.

- ↑ Examples are offered by Jacob Grimm, Wilhelm Grimm: German Dictionary , Vol. 7, Leipzig 1889, Sp. 1900 f .; Günther Drosdowski (Ed.): Duden. The large dictionary of the German language in six volumes , Vol. 5, Mannheim 1980, p. 2005; Ruth Klappenbach, Wolfgang Steinitz: Dictionary of German Contemporary Language , Berlin 1975, p. 2810 (there, “platonic love” is defined as spiritual, not sensual love between man and woman ). Cf. Maximilian Bergengruen: From the beautiful soul to the good state . In: Stefan Matuschek (ed.): Where the philosophical conversation turns completely into poetry. Plato's Symposium and its Effect in the Renaissance, Romanticism and Modern Age , Heidelberg 2002, pp. 175–190, here: 178.

- ^ Thomas Gould: Platonic Love , London 1963, p. 1.

- ↑ See Karin Sporkhorst: From which, remarkably, nothing emerges. Diotima - a woman with a past but no future . In: Gabriele Uerscheln (Ed.): "Perhaps the truth is a woman ..." Female figures from Mythos im Zwielicht , Cologne 2009, pp. 112–121.

- ^ Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff: Platon. His life and his works , 5th edition, Berlin 1959 (first published in 1919), p. 369.

- ↑ Olof Gigon: Introduction . In: Platon: Meisterdialoge (= anniversary edition of all works , vol. 3), Zurich / Munich 1974, pp. V – LXXXVI, here: LIX.