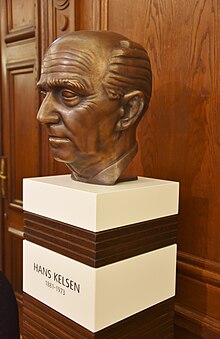

Hans Kelsen

Hans Kelsen (born October 11, 1881 in Prague , Bohemia , Austria-Hungary , † April 19, 1973 in Orinda near Berkeley , USA ) is considered one of the most important legal scholars of the 20th century. He made outstanding contributions in particular in constitutional law , international law and as a legal theorist . Together with Georg Jellinek and the Hungarian Félix Somló, he belonged to the group of Austrian legal positivists , whose thinking he significantly influenced with his main work, Pure Legal Theory. As early as 1920, Kelsen declared respect for the minority as the “highest value” of representative democracy and is considered the architect of the Austrian Federal Constitution of 1920, most of which is still in force today. Alongside H. L. A. Hart, he is regarded as the most influential exponent of legal positivism in the 20th century.

Life

Kelsen came from a German-speaking Jewish family in Prague. The father Adolf Kelsen (1850-1907) came from Brody in eastern Galicia , his mother Auguste Löwy (1860-1950) from Neuhaus in Bohemia .

Studies and teaching in Vienna

The family soon moved to Vienna ; his father wanted to expand his lamp business there. Hans first attended a private Protestant primary school . Because of his father's financial difficulties, Kelsen then had to attend a municipal elementary school, which he felt as a humiliation throughout his life. Then he graduated from the elite academic high school in Vienna . One of his school colleagues was Ludwig von Mises , later professor of economics and an advocate of economic liberalism . In 1905 Kelsen converted to Roman Catholicism ; In 1912 he moved to the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession .

Kelsen studied at the University of Vienna Law and habilitated in 1911 in constitutional law and legal philosophy . He also attended a seminar at Heidelberg University , where he met the constitutional law professor Georg Jellinek (1851-1911). In 1912 Kelsen married Margarete Bondi (1890–1973). The couple had two daughters: Hanna (1914–2001) and Maria (1915–1994).

In 1917 Kelsen became an associate professor at the University of Vienna, and in 1919 a full professor . His students included Hersch Lauterpacht and Leo Gross , among others .

Adviser to the last Austro-Hungarian War Minister

During the First World War , Kelsen was initially classified as unfit for service and briefly employed in the central shirt issuing office. As a result, as an employee of the last Austro-Hungarian War Minister , Rudolf Stöger-Steiner , he was involved in military-political plans that were based on the expected replacement of the Austro-Hungarian Real Union by a mere personal union.

Kelsen dealt u. a. in an article which then required division of the Imperial Army in an Austrian and a Hungarian army. This division finally took place on October 31, 1918 on the basis of the decision of Hungary to terminate the Real Union, sanctioned by Emperor Charles I in his function as King Charles IV of Hungary. However, the common minister of war, who were joint Council of Ministers or the kk Austrian government to no longer be involved.

In October 1918, Kelsen drafted a constitutional memorandum with plans to avoid an economic and political catastrophe in the area of the monarchy. Heinrich Lammasch and Kelsen then personally received the official order from the emperor at the headquarters in Baden to form a "liquidation commission", which had to conduct constitutional negotiations to "save the community". The subsequent negotiations, which Lammasch conducted with the representatives of the various nationalities, were initially favorable. But on October 20, 1918, Lammasch Kelsen reported that the mission was not feasible because of the refusal of Czech politicians to participate. Kelsen took over the notification of the emperor in Gödöllö . Immediately afterwards, Lammasch, Redlich and Kelsen prepared the list of ministers of the Lammasch government , the liquidation ministry, to be proposed to the emperor, which then only held office for two weeks before the emperor gave up.

Constitutional Expert of the Republic of Austria

After the proclamation of the state of German Austria, founded on October 30, 1918, as a republic on November 12, 1918, Kelsen was repeatedly consulted by the Social Democratic State Chancellor Karl Renner as an expert on constitutional issues. In March 1919 he was charged with drafting the constitution of the new state. Launched by the Constituent National Assembly adopted federal constitutional law from 1 October 1920, not, as is often written by him alone, but has played a major part of it. The so-called B-VG (the hyphen separates it from federal constitutional laws enacted on the basis of the constitution) applies in the version from 1929 (strengthening the rights of the Federal President, redesign of the Constitutional Court) with the modifications made by the EU accession in 1995 to today.

Constitutional judge

In 1919, Kelsen became a member of the Constitutional Court (VfGH) as an independent expert . His work as a constitutional judge and, above all, his alleged closeness to the Social Democratic Party earned him a lot of criticism after conservative governments took office from 1920. The Social Democratic Mayor of Vienna Jakob Reumann had, contrary to the request of the conservative Interior Minister, not forbidden the performance of Arthur Schnitzler's “ Reigen ”; the federal government's indictment against Reumann before the Constitutional Court failed. Furthermore, Reumann had a crematorium built in Vienna without government approval ; the VfGH recognized that it had found itself in an excusable legal error.

The conservatives took particular offense at a family law decision of the Constitutional Court. The divorce was not yet introduced in Austria. The Social Democratic governor of Lower Austria, Albert Sever , had, however, permitted civil remarriage after a separation by dispensation; one spoke of so-called dispensary marriages or sever marriages . If the Supreme Court , called on by the Federal Government, had declared these marriages invalid, the Constitutional Court did not lift the dispensation and thus sparked angry reactions from the Catholic Church and the Christian Socialists . Kelsen was accused of being the spiritual father of this VfGH knowledge.

On the occasion of the redesign of the Constitutional Court in 1929/30, the mandates of the previous constitutional judges were terminated ex lege. The conservative federal government did not include Kelsen in its nomination proposal to the Federal President for mandates to be filled by it on the basis of the constitutional amendment of 1929 . The Social Democrats, the strongest faction in the National Council , offered him to include him on the list of constitutional judges to be elected by the National Council. Kelsen turned down the offer because he did not want to be a judge by the grace of a party.

Kelsen in Cologne, Geneva and Prague

Kelsen subsequently left Austria and in 1930, at the suggestion of Lord Mayor Konrad Adenauer (Catholic Center Party ), became professor for international law at the University of Cologne . There he was in 1933 after Hitler came to power because of its known democratic views and his Jewish heritage on the basis of NS - Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil on leave April 7, 1933 from his post as a university lecturer. Carl Schmitt was the only faculty colleague who did not join a petition addressed to the Prussian government by the Faculty of Law in favor of Kelsen. In 1933, Kelsen was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . In 1934 he was retired as a professor at the University of Cologne.

In 1933, Kelsen took up a professorship for international law at the Institut universitaire de hautes études internationales in Geneva, where he taught until 1940. In 1936 he was also appointed by the Czechoslovak government as full professor for international law at the Karl Ferdinand University in Prague (until 1938). In 1936 Kelsen (losing the German and Austrian) acquired Czechoslovak citizenship. Kelsen's appointment to Prague sparked violent protests by German “ethnic” and National Socialist students. After only three semesters, his work in Prague ended.

Kelsen in the United States

In 1940 Kelsen emigrated to the USA . He received an honorary doctorate from Harvard University , but no permanent position. In 1942 he moved to the University of California, Berkeley , where he was appointed "Full Professor" in 1945 and taught political science until 1957.

After 1945, Kelsen was accepted by Austria into the Austrian Academy of Sciences and officially honored, but not invited to return to Vienna.

Kelsen died as a result of cardiac arrest on April 19, 1973 at 11 a.m. in the Orinda Hospice . Cremated at his own request, his ashes were scattered in the Pacific.

Kelsen's main fields of activity

overview

Kelsen, who was philosophically close to the Marburg Neo-Kantianism , was the founder of the pure legal theory , with which he put legal positivism on a new theoretical basis. The constitutional jurisdiction he shaped served as an example throughout Europe. He received eleven honorary doctorates ( Utrecht , Harvard , Chicago , Mexico City , Berkeley, Salamanca , FU Berlin , Vienna, New School for Social Research New York , Paris , Salzburg ) for his life's work.

Spiritual antipodes were Carl Schmitt , Hermann Heller or Rudolf Smend , who had a more sociological understanding of law, sometimes referred to as "humanities" (see also the legal and the "sociological" concept of the state in Weimar state theory ).

A central concern of Kelsen was the defense of freedom, especially intellectual freedom, against all forms of oppression. These ideas of the democratically and ideology-critical legal philosopher found expression in his classic writing State Form and Weltanschauung as well as in the essay "Defense of Democracy".

Legal theory

Hans Kelsen was described by Horst Dreier as the “lawyer of the 20th century”. In fact, his striving for a formal analysis of the law was formative for the German-speaking area. In doing so, Kelsen took a purely formal point of view, which he had already worked out in the main problems of constitutional law : In turning away from Georg Jellinek, for the first time he no longer understood the state in terms of the sociologically factual categories of “people, territory and authority”. Rather, Kelsen saw the state as the totality of legal obligations. Therefore, the main feature of the state, following Kant, is the existence of an objective legal system.

The individual legal norms are conditioned in their development by a higher legal norm in the norm pyramid developed by Adolf Merkl , and each legal norm in turn causes a norm of lower rank to arise ( tiered structure of the legal system ). However, this leads to an infinite regress , since a higher one would have to be above every norm. To solve this problem, Kelsen introduced what is known as the basic hypothetical norm .

The hypothetical basic norm serves as a transcendental logic requirement in order to guarantee the coherence of a legal system. A norm only belongs to a legal system if it can be traced back to this basic norm. Originally, Kelsen thought that the basic norm was a hypothesis , later he went on to see it as a fiction.

Kelsen attached great importance to the distinction of categories Shall and his (see is-ought problem ). Based on the fact that something is, it cannot be concluded that it should be so. There are therefore different categories of thought in the sense of Immanuel Kant . Norms belong to the area of the ought. Their specific existence is called validity. A norm can only derive its validity from another - higher - norm, never from a mere fact (such as power).

According to Kelsen, the subject of jurisprudence is exclusively legal norms. There are of course other systems of norms such as custom and morality; but the latter is the subject of ethics , which is concerned with norms of morality. In his presentation of applicable law, the legal scholar does not have to examine whether a norm appears just or unjust according to certain moral concepts. This would be an unreliable confusion of different systems of norms and contradict the demand for purity of legal doctrine.

It is characteristic of Kelsen's system that he opposes “ natural law ” for methodological reasons . A system of legal principles is referred to as "natural law" in which the constant nature of man as a rational being is derived from the nature of things, with the origin as well as the validity being independent of human action, so that it is above the positive legal order be able to lead an independent existence. In this context, the question arises as to what the hypothetical basic norm should be other than natural law or a norm from the nature of the thing.

But Kelsen also admitted that ethical and sociological questions play a role in shaping and creating laws.

sociology

In the field of sociology, his correspondence with Eugen Ehrlich (Kelsen-Ehrlich debate) should be mentioned in particular , in which Kelsen's legal positivism meets Ehrlich's understanding of law, which opposes the then still prevailing conceptual jurisprudence through a stronger reference to legal reality. In this discussion, Kelsen made a distinction between sociology and law . The strict separation is based on the fact that sociology is just as much a science as mathematics, like any natural science. What these sciences have in common is that they make statements about something that is accessible to evidence and can thus be determined as true or false. However, jurisprudence is a must-do science whose statements can neither be verified nor falsified. This is due to the fact that jurisprudence only makes statements about whether something should be, whether something should apply, be done, tolerated or omitted. Such statements can only be valid or not valid. The sociological and legal concept of the state from 1922 is regarded as his most important work in this field .

Democracy theory

Kelsen himself was an advocate of democracy , for whom he formulated the principle of majority and legitimate opposition in the sense of modern pluralism as early as 1920 and justified it with the relativism of ideological convictions. Against the Soviet form of dictatorship, which presents itself to him as the “absolutism of a political dogma” and “party rule that represents this dogma”, he declared in 1920 that democracy's “highest value” was that it “valued the political will of everyone equally” and “ every political belief, every political opinion ... equally respects ”. This has consequences: “The rule of the majority, which is so characteristic of democracy, differs from any other rule in that it not only conceptually presupposes an opposition - the minority - according to its innermost essence, but also recognizes it politically and in the basic rights and freedom , in the principle of proportionality. ”The politics of democracy, according to Kelsen, is“ a politics of compromise ”. In his memorandum Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie , first published in 1920, he discussed the principle of democratic representation in depth .

Also in 1920, Kelsen's exploration of Marxism was published under the title Socialism and the State: An Inquiry into the Political Theory of Marxism . For Kelsen, socialism was only possible through the state, but not without the state. He gave Ferdinand Lassalle's idea of state socialism preference over Marxist theory.

Constitutional law

Kelsen is rightly seen as the founder of modern constitutional justice. Although he is widely regarded as the creator of the Austrian Federal Constitution of 1920, he only worked on the sub-area of constitutional jurisdiction . The basic idea was to have the legislative acts (legal creation acts) checked in the last instance by a court that was separated from the specialized jurisdiction. This enables uniform application of the law and counteracts legal fragmentation. The fact that Kelsen's theory was not fully implemented in practice was shown by the dispute between the specialized courts and the Austrian Constitutional Court , at which Kelsen was a judge, over the interpretation of the requirements for divorce. While Kelsen and the Constitutional Court were convinced that an effective divorce already existed in the event of a state divorce decision, the specialized courts insisted that a church act was required for this. The result was that Kelsen resigned his judge's office and left Vienna.

In Cologne, Kelsen met Carl Schmitt and responded to his view of the state with the text Who should be the guardian of the constitution . Schmitt propagated the system of absolute power with the thesis “Whoever decides on a state of emergency is sovereign”, Kelsen countered the principle of constitutional jurisdiction.

In the course of the conformity with the seizure of power , Kelsen was asked to leave the University of Cologne. A petition signed by the entire Cologne law school with the exception of Carl Schmitt was unsuccessful.

international law

The legal theoretical considerations for the construction used in the case of the four-power status such as the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht go back to work by Kelsen.

The Allies had already been aware during the Second World War that in the event of the military occupation of Germany they would no longer find a government capable of acting. The Allies took over the tasks of the defeated German Reich as a subject of constitutional and international law as a whole without appropriating them.

During his time at Berkeley, Kelsen dealt more intensely with the application of his doctrine of norms to international law. He wrote a commentary on United Nations law that is still largely valid today .

Honors and Research

Awards (excerpt)

- 1938: Honorary membership of the American Society for International Law

- 1953: Karl Renner Prize

- 1960 International Antonio Feltrinelli Prize

- 1961 Grand Cross of Merit with Star of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 1961 Austrian Decoration for Science and Art

- 1961 honorary doctorate from the University of Vienna

- 1966 Ring of Honor of the City of Vienna

- 1967 Large Silver Medal of Honor with the Star for Services to the Republic of Austria

- 1967 Honorary doctorate from the University of Salzburg

- 1967 Corresponding member of the British Academy

- In 1981, Kelsenstrasse in Vienna ( Landstrasse district ) was named after him.

Hans Kelsen Institute and Hans Kelsen Research Center

On the occasion of the 90th birthday of Hans Kelsen, the Austrian federal government decided on September 14, 1971 to set up a foundation called the "Hans Kelsen Institute". The institute started its activity in 1972; Its task is to document Pure Legal Doctrine and its scientific echoes at home and abroad, to inform about it and to promote the further penetration, continuation and development of Pure Legal Doctrine. For this purpose, the Manz publishing house is issuing its own series of publications, in which 33 volumes have so far appeared. The institute administers Kelsen's rights to his publications and keeps his scientific legacy, from which writings have been and are repeatedly published posthumously (for example, the General Theory of Norms in 1979 ).

Kurt Ringhofer and Robert Walter were appointed managing directors of the Hans Kelsen Institute in 1972 , and they held this position until their deaths in 1993 and 2010, respectively. The current managing directors are Clemens Jabloner (since 1993) and Thomas Olechowski (since 2011).

In 2006, the "Hans Kelsen Research Center" was founded at the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg under the direction of Matthias Jestaedt . After he was appointed to the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg in 2011, the research center was also transferred there. In cooperation with the Hans Kelsen Institute, the Hans Kelsen Research Center publishes a historical and critical complete edition of Kelsen's works by Mohr Siebeck Verlag .

Fonts (selection)

- The doctrine of the state of Dante Alighieri. Deuticke, Vienna / Leipzig 1905.

- Main problems of constitutional law, developed from the doctrine of legal propositions . Mohr, Tübingen 1911, 2nd, photo-mechanically printed edition 1923 increased by a preface.

- On the nature and value of democracy Mohr, Tübingen 1920; 2nd, revised and expanded edition 1929; Reprint of the 2nd edition: Scientia, Aalen 1981, ISBN 3-511-00058-0 .

- Socialism and the State: An Inquiry into the Political Theory of Marxism. Hirschfeld, Leipzig 1920; 3rd edition: Wiener Volksbuchhandlung, Vienna 1965.

- Austrian constitutional law: an outline of the development history . Mohr, Tübingen 1923.

- General political theory. Springer, Berlin 1925.

- The philosophical foundations of natural law and legal positivism. R. Heise, Charlottenburg 1928.

- Who should be the guardian of the constitution? W. Rothschild, Berlin-Grunewald 1931.

- Pure legal theory: Introduction to legal problems. Deuticke, Leipzig / Vienna 1934; 2nd, completely revised and expanded edition: Deuticke, Vienna 1960.

- Retribution and Causality: A Sociological Inquiry. WP van Stockum, The Hague 1941.

- General Theory of Law and State. Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1945.

- Society and Nature: A Sociological Inquiry. Kegan Paul, London 1946.

- The Law of the United Nations: a critical analysis of its fundamental problems. Stevens, London 1950.

- What is justice Deuticke, Vienna 1953.

- Principles of International Law. Rinehart, New York 1952; 2nd edition 1966.

- General theory of norms. On behalf of the Hans Kelsen Institute from the estate ed. by Kurt Ringhofer u. Robert Walter . Manz, Vienna 1979.

- Works. Edited by Matthias Jestaedt. In cooperation with the Hans Kelsen Institute. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007 ff., ISBN 978-3-16-149420-8 .

literature

- Brunkhorst, Hauke (ed.): Legal state: State, international community and international law in Hans Kelsen , Nomos, Baden-Baden 2008.

- Ehs, Tamara (ed.): Hans Kelsen. A political science introduction. Facultas, Vienna 2009.

- Fränkel, Karl Joachim: Law and justice with Hans Kelsen. Diss. Cologne 1965.

- Heidemann, Carsten: The norm as a fact. On the theory of norms by Hans Kelsens , Nomos, Baden-Baden 1997.

- Klug, Ulrich: Principles of the Pure Doctrine of Law - Hans Kelsen for memory (= Cologne University Speeches. No. 52). With a speech by Klemens Pleyer Scherpe, Krefeld 1974.

- Koja, Friedrich (ed.): Hans Kelsen or the purity of legal theory. Böhlau Verlag, Vienna-Cologne-Graz 1988.

- Dreier, Horst : Legal studies, state sociology and theory of democracy with Hans Kelsen. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1986.

- Jestaedt, Matthias (ed.): Hans Kelsen. Works. Volume 1. Published writings 1905–1910 and personal reports. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-16-149419-2 .

- Jöckel, Wilhelm: Hans Kelsen's legal theoretical method. Presentation and criticism of its foundations and main results. Scienta, Aalen 1977.

- Reader, Norbert : Hans Kelsen (1881–1973). In: New Austrian Biography. Vol. 20, Vienna 1979, pp. 29-39.

- Marra, Realino: Liberi da Kelsen. Per un vero realismo giuridico. In: Materiali per una storia della cultura giuridica. Vol. 42, H. 1, 2012, pp. 263-280.

- Métall, Rudolf Aladár: Hans Kelsen: life and work. Deuticke, Vienna 1969.

- Métall, Rudolf Aladár (Ed.): 33 contributions to pure legal theory. Vienna 1974.

- Oberkofler, Gerhard / Rabofsky, Eduard: Hans Kelsen in the war effort of the kuk Wehrmacht: A critical appraisal of his military theoretical offers (legal history series 58). Frankfurt a. M. u. a. 1988.

- Thomas Olechowski : Hans Kelsen: Biography of a legal scholar , Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2020, ISBN 978-3-16-159292-8

- van Ooyen, Robert Chr .: The state of modernity. Hans Kelsen's theory of pluralism. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2003.

- van Ooyen, Robert Chr. (Ed.): Hans Kelsen: Who should be the guardian of the constitution? Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2008.

- van Ooyen, Robert Chr .: Hans Kelsen and the open society. Publishing house for social sciences, Wiesbaden 2010.

- Paulson, Stanley L. / Stolleis, Michael (Eds.): Hans Kelsen. Constitutional law teacher and legal theorist of the 20th century. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2005.

- Pils, Ramon: Terminology dictionary Hans Kelsen. German-English glossary for translation practice (= series of the Hans Kelsen Institute 37). Manz, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-214-14758-7 .

- Römer, Peter : Hans Kelsen. Dinter, Cologne 2009, ISBN 978-3-924794-54-5 .

- Schefbeck, Günther: Hans Kelsen and the Federal Constitution. In: Bezirksmuseum Josefstadt (Ed.): Hans Kelsen and the Federal Constitution. History of a career in Josefstadt. Exhibition catalog. Vienna 2010, pp. 48–57.

- Schild, Wolfgang : The two systems of pure legal theory. A Kelsen interpretation. In: Wiener Jahrbuch für Philosophie. 4: 150-194 (1971).

- Schlüter-Knauer, Carsten: The controversial democracy: Carl Schmitt and Hans Kelsen with and against Ferdinand Tönnies . In: Uwe Carstens u. a .: Constitution, constitution, constitution , Books-on-Demand, Norderstedt 2008, pp. 41–86

- Sciacca, Fabrizio: Il mito della causalità normativa. Saggio su Kelsen. Giappichelli, Torino 1993.

- Stifter, Christian H .: Between spiritual renewal and restoration. American plans for denazification and democratic reorientation and the post-war reality of Austrian science 1941–1955 . Böhlau, Vienna - Cologne - Weimar 2014, pp. 393–403. [2]

- Robert Walter: Kelsen, Hans. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 11, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-428-00192-3 , p. 479 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Walter, Robert : Hans Kelsen as constitutional judge. Manz, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-214-07673-6 .

- Walter, Robert / Ogris, Werner / Olechowski, Thomas (eds.): Hans Kelsen: Life, work, effectiveness. Manz, Vienna 2009.

- Ziemann, Sascha: The "International Journal for Theory of Law" / "Revue Internationale de la Théorie du Droit" (1926 to 1939). Introductory remarks on the first modern legal theory journal along with bibliography and index. In: Legal Theory. 2007, Issue 1, pp. 169–195 (contains a bibliography for the journal co-edited by Kelsen).

Web links

- Literature by and about Hans Kelsen in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Hans Kelsen in the German Digital Library

- The Pure Theory of Law. Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Freely accessible volumes of the academy project "Hans Kelsen Works"

- Hans Kelsen Institute Vienna (works, curriculum vitae, research)

- Hans Kelsen Research Center

- A short biography of Hans Kelsen from the Wiener Zeitung ( Memento from June 5, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- Horst Dreier: Hans Kelsen (1881-1973): “Jurist of the Century”? (PDF file; 121 kB)

- Andreas Kley and Esther Tophinke: Overview of the pure legal theory (PDF file; 177 kB)

- Various articles on the life and work of Hans Kelsen from The European Journal of International Law (1998)

- Newspaper article about Hans Kelsen in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Eric Frey: Early exile without conciliatory homecoming , report on the scientific Kelsen biography currently written by Thomas Olechowski, in: Daily newspaper Der Standard , Vienna, March 3, 2010, p. 16

- ↑ See details on this in Rudolf A. Métall, Hans Kelsen. Life and Work , Vienna 1969, p. 69 ff

- ↑ H. Kelsen, published writings 1905-1910 and personal reports. Tübingen 2007. p. 91.

- ↑ Hans Kelsen, Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie, p. 36 (1920) online: [1]

- ^ Matthias Etzel, The repeal of National Socialist laws by the Allied Control Council (1945–1948), Volume 7 of Contributions to the Legal History of the 20th Century, Verlag Mohr Siebeck, 1992, ISBN 3-16-145994-6

- ^ HR Klecatsky / Rene Marcic / Herbert Schambeck (eds.): The Viennese legal theory school: writings by Hans Kelsen, Adolf Merkl, Alfred Verdross , Verlag Österreich, 2010, p. 1933.

- ↑ Vienna City Hall Correspondence, December 22, 1953, sheet 2102

- ↑ Vienna City Hall Correspondence, January 16, 1954, sheet 67

- ↑ Honorary doctorate from the University of Vienna

- ^ Deceased Fellows. British Academy, accessed June 17, 2020 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kelsen, Hans |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian-American legal scholar |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 11, 1881 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Prague |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 19, 1973 |

| Place of death | Berkeley , California |