Round dance (drama)

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Round dance |

| Genus: | Ten dialogues |

| Original language: | German |

| Author: | Arthur Schnitzler |

| Publishing year: | 1900/1903 |

| Premiere: | December 23, 1920 |

| Place of premiere: | Small theater in Berlin |

| Place and time of the action: | Vienna, around 1900 |

| people | |

|

|

Dance is the most successful stage play by Arthur Schnitzler . He wrote the first version between November 23, 1896 and February 24, 1897. The first complete performance took place on December 23, 1920 at the Kleiner Schauspielhaus in Berlin and was one of the biggest theater scandals of the 20th century.

In ten erotic dialogues, the piece depicts the “relentless mechanics of cohabitation” (which is not shown in the piece itself) and its environment of power, seduction, longing, disappointment and the desire for love. It paints a picture of morality in the society of the fin de siècle and migrates in a dance all social classes from the proletariat to the aristocracy . After its world premiere in 1920, the play triggered a theatrical scandal in both Berlin and Vienna and led to the so-called "Reigen Trial", after which Schnitzler imposed a performance ban for the play, which was in force until January 1, 1982 was circumvented by various films and a vinyl recording.

content

Ten people meet each other in pairs, they have ten dialogues and each time the couple finds a sexual union. Schnitzler uses the dance form of round dance as a structural principle , in which one figure always extends the hand of a new figure for the next scene. Schnitzler only describes the situations before and after coitus , the sexual intercourse itself is not shown, it is only indicated in the text with dashes. After each scene, a partner is exchanged and the social ladder climbed, from the prostitute , soldier and housemaid to the young man , wife , husband and sweet girl to the poet , actress and count , who at the end meets the prostitute again and so on the "round dance" closes.

- The prostitute and the soldier

Late night. At the Augarten Bridge .

The prostitute speaks to a soldier on the street who is on his way home to the barracks. Because it is too far for him to get to her accommodation and he has no more time until the tattoo, she persuades him to stay with her and lures him with the words “Go, stay with me now. Who knows if we'll still have life tomorrow. ”To sexual intercourse. Afraid of being discovered by the police, the two descend to the river bank. - After coitus, the soldier is in a hurry to get away from the prostitute and into the barracks. After she had offered herself to him beforehand for free, since she asked for money "only from civilians", the soldier finally refused the prostitute the little money she needed for the caretaker . Mocking her name Leocadia, he runs off, the whore curses after him and his brutality.

- The soldier and the maid

Prater . Sunday evening. A path that leads from the Wurstelprater into the dark avenues. Here you can still hear the confused music from the Wurstelprater, also the sounds of the five-cross dance, an ordinary polka played by brass.

The soldier and the housemaid who go out walk late in the evening from a dance establishment in Vienna's popular Prater amusement park into the nearby meadows. Other lovers are already lying around her in the grass, the girl is scared and wants to go back. The soldier offers her the you-word , doesn’t make long detours and seduces her. - During the love hug the maid complains, “I can't see your face at all”, the soldier replies laconically: “A what - face!” And attacks her one more time. - After coitus the soldier is sobered, he wants to go straight back to the dance hall to continue the evening with friends and to make new conquests, he doesn't have to be in the barracks until midnight, but the maid has to go home. Reluctantly, he offers her his company if she wants to wait for him and invites her for a glass of beer. Then he is already dancing with the next one.

- The maid and the young man

Hot summer afternoon. - The parents are already in the country. - The cook is out. - In the kitchen, the maid is writing a letter to the soldier who is her lover. The doorbell rings from the young gentleman's room. She gets up and goes into the young gentleman's room. The young gentleman is lying on the divan , smoking and reading a French novel.

Alfred, son from a good family, is at home alone on Saturday afternoon, his parents have gone to the country, only the maid Marie is there. She is sitting in the kitchen and writing a love letter to the soldier. The atmosphere is hot and humid, there is something in the air. Again and again the young man lures Marie from the kitchen to his room with pretended wishes. Finally he boldly confesses to her that he has secretly observed her undressing, and begins to undress her. She defends herself pro forma: “Oh God, but I didn't even know that Mr. Alfred could be so bad”, but gives in and Alfred falls on her. - The doorbell rings. This is a welcome excuse for the young gentleman to send Marie to have a look, even though the doorbell has probably been rang for a long time, although she asserts that she “always paid attention” during traffic. When she comes back, the young gentleman keeps his distance and flees from her tenderness to the coffee house. The maid steals a cigar from his desk for her lover, the soldier.

- The young gentleman and the young woman

Eve. - A salon furnished with banal elegance in a house on Schwindgasse. The young man has just come in and is lighting the candles while still wearing his hat and overcoat . Then he opens the door to the next room and looks inside. The light from the candles in the salon extends over the parquet to a four-poster bed. (…) It rings. The young gentleman starts slightly. Then he sits down on the armchair and does not rise until the door is opened and the young woman enters.

Alfred, the young man, has a rendezvous with Emma, a married woman. He makes all possible preparations until she finally appears. She is veiled, yet very nervous about being seen and discovered in her adultery, and vows to stay short. The two had a rendezvous outside before, but this time things get serious with the help of the sister who serves as an alibi. Alfred swarms her with oaths of love and finally carries his beloved into the bedroom. - The intention fails, Alfred is too nervous, there is no traffic. The young gentleman tries to excuse his failure verbatim with a quote from a novel by Stendhal in which a company of cavalry officers recounts their love affairs. "And everyone reports that with the woman he loved most, you know, most passionately ... that he, that he - that is, in short, that everyone has felt the same way with this woman as it is now for me. “Emma feigns understanding for the predicament, but ironizes the fact with the consolation that from now on they are nothing but“ good comrades ”. But when Emma stimulates Alfred orally, his manhood returns. - Both are proud and fulfilled and arrange to meet for a dance the next day at a social ball and then back in the apartment the day after.

- The young wife and the husband

A comfortable bedchamber. It's half past ten in the morning. The woman lies in bed and reads. The husband is just stepping into the room in his dressing gown.

On the same day in the evening (this is not clear from the text, but it can be assumed) the young woman meets her husband in the marriage bed, who after a busy day praises the difficulties of the love life before marriage : “You hear a lot and you know too much and actually read too much, but you don't have a proper understanding of what we men actually experience. What is commonly called love is made very thoroughly repugnant to us. ”He hypocritically regrets the fate of the“ sweet girl ”who gives herself to love unmarried:“ You, who were you young girls from a good family, who were calm could wait under the care of your parents for the man of honor who desires you to marry; - You do not know the misery that drives most of these poor creatures of sin into their arms. […] I don't just mean material misery either. But there is also - I would like to say - a moral misery, a lack of understanding of what is permissible, and especially of what is noble. ”He speaks about the immorality of adulteresses, which he warns against. Emma tries cautiously to defend these women by assuming they have "pleasure" in cheating. The husband is outraged and describes their lust only as "superficial intoxication" . Then, conscious of his moral sovereignty, he loves his wife. - After the intercourse, the memory of the honeymoon in Venice returns to the wife. She gently indicates that she would like to enjoy her husband's passion more often. This blocks and turns to sleep.

- The husband and the sweet girl

A cabinet particulier in the Riedhof. Comfortable, moderate elegance. The gas stove is burning. The remains of a meal can be seen on the table: cream meringue, fruit, cheese. In the wine glasses a Hungarian white wine. The husband is smoking a Havana cigar, he is leaning in the corner of the divan. The sweet girl is sitting next to him on the armchair and spoons the top foam out of a meringue, which she sips with pleasure.

The husband approached a “ sweet Viennese girl ” on the street and persuaded him to go to the extra room of an inn with him, where he paid her for dinner. She enjoys the unfamiliar luxury. Both lie to each other, he about his place of residence and his marriage, she about their innocence. The husband is intoxicated by the youth of the 19-year-olds, the wine is used as an excuse, it seduces them. ––– While the girl is still dreaming blissfully, the husband suddenly reproaches himself for the careless encounter, he even suspects her of prostitution. The husband intrudes on her and wants to know more about her past, but pretends he lives away in order not to commit. The sweet girl complains about the change in his behavior: “Do you really want to send me home? - Go, you're like a changed man. What have I done to you? ”The husband even accuses her of having seduced him to be unfaithful, and when she speaks lightly about adultery:“ Ah what, your wife certainly doesn't do it any differently than you, ”he says indignantly sums up: "You are really strange creatures, you ... women." He plans a permanent liaison with her, but exhorts the girl to lead a moral life, which he makes a condition.

- The sweet girl and the poet

A small room furnished with a cozy taste. Curtains that make the room semi-dark. Red stores. Large desk with papers and books lying around. A pianino on the wall. You just come in together. The poet closes.

The successful poet took the cute girl home with him after a walk. The spiritual worlds of the two are fundamentally different, his is that of poetry, hers is profane everyday life. He enjoys its simplicity, which he tenderly calls stupidity. Inspired by her presence, he begins to write poetry, in the twilight he suddenly believes that he has forgotten what she looks like: “It's strange, I can't remember what you look like. If I couldn't remember the sound of your voice either ... what would you actually be? - Near and far at the same time ... “The sweet girl talks about herself, but uses the same stories and excuses that she used with her husband before. After playing the piano for her, the poet dreams of an “Indian castle” with her and seduces her. - In the exuberance of sexual bliss after coitus, the poet reveals his name to his lover: Biebitz. But she doesn't know the name and he philosophises about the fame that women usually bring him. He turns on the light and looks at the nakedness of the girl who is ashamed: "You are beautiful, you are the beauty, you may even be the nature, you are the holy simplicity." She declines to meet again the next day with the excuse of being more familiar Commitments. The poet invites her to visit one of his plays in the Burgtheater in order to learn everything about her: "I will only know you completely when I know what you felt about this play."

- The poet and the actress

A room in an inn in the country. It is a spring evening, the moon lies over the meadows and hills, the windows are open. Great silence. Enter the poet and actress; as they enter, the light that the poet holds in his hand extinguishes.

The poet and actress rented a room in a country inn for the weekend to start the long overdue affair. The successful diva is full of airs and moods, she torments the poet, in whose pieces she plays, with the alternation of closeness and distance and lets him feel both rejection and sweet promise. The poet raves about her: "You have no idea what you mean to me ... You are a world of your own ... You are the divine, you are the genius ... You are ... You are actually the holy simplicity." She uses that Zimmer as a private stage and takes chaste religious poses, teases the poet with silly nicknames, stirs up his jealousy and even sends him out of the room so that he can undisturbed. After exhausting all the refinements, she finally lets him in. - According to the résumé “It's nicer than playing in stupid pieces”, the actress continues her taunts and humiliating nicknames even after coitus, in return the poet violates her vanity by telling her that he will not have her performance the day before has visited. In pathetic words the actress confesses her love for the poet: “What do you know about my love for you. Everything leaves you cold. And I've been lying in a fever for nights. Forty degrees! "

- The actress and the count

The actress's bedroom. Very lavishly furnished. It is twelve noon, the rouleaux are still down, a candle is burning on the bedside table, the actress is still in her four-poster bed. There are numerous newspapers on the ceiling. The count enters in the uniform of a dragoon rider .

The actress is in bed, she is "indisposed", so she has her days . The Count waits for her to congratulate her on the previous day's performance, which was a triumph, but she only took the Count's flowers home with her. The actress lives in grand gestures, she kisses the count's hand and calls him a “young old man”, he admits that he is ignorant of the theater world, but confesses to an affair with a ballet girl. In their misanthropy, which is a dramatic pose for the actress and a philosophical attitude for the Count, the two find a soulmate. The Count philosophizes about the enjoyment of love: “As soon as you don't give in to the moment, that is, think of later or earlier ... well, it's over in a minute. Later ... is sad ... earlier is uncertain ... in a word ... you just get confused. "And would like to include the soul:" I think that's a wrong view that you can separate them. "He asks for a meeting after the evening theater performance, but the actress seduces him on the spot. - The count, trying to keep his feet up, initially refuses to meet again after the theater and does not want to come back until the day after next, but the actress forces him to go on a rendezvous. She suspects physical exhaustion in him, but he wants a mental distance, to which she replies in a male-chauvinistic manner: “What is your soul to me? - Leave me alone with your philosophy. If I want that, I'll read books. ”After the theater, she orders him to sleep in her apartment again.

- The Count and the Whore

Tomorrow, around six o'clock. A poor room, one-windowed, the dirty yellow roulettes are let down. Worn greenish curtains. A chest of drawers with a few photographs on it and a noticeably tasteless, cheap lady's hat. Cheap Japanese fans behind the mirror. On the table, which is covered with a reddish protective cloth, there is a kerosene lamp that burns slightly, a yellow paper lampshade, next to it a mug with a leftover beer and a half-empty glass. On the floor next to the bed there are untidy women's clothes, as if they had just been thrown off quickly. The prostitute lies asleep in bed, she breathes calmly. - On the divan, fully dressed, lies the count in a drappable overcoat, the hat lies on the floor at the head of the divan.

The scene begins with a monologue in the style of Schnitzler's inner monologues in his stories (for example in Lieutenant Gustl ). The count wakes up early in the morning in the whore's room and tries to remember the previous night of drinking. He assumes that he has not slept with the girl, looks at her and compares her blissful sleep with "his brother", death. When Leocadia, the prostitute, wakes up, he learns that she is twenty, intends to move downtown and has been with her business for a year. But she destroys his romantic illusion that nothing happened between them, which he regrets very much in his decadence: "It would have been nice if I had only kissed her on the eyes. It was almost an adventure ... I just wasn't meant to. ”This is the only scene in which the couple don't sleep together and in which there is therefore no second half. When the count leaves, the cleaning lady is just beginning her day's work outside, and the count thoughtlessly wishes her good night. She wishes him "good morning".

Emergence

Schnitzler's plan for the round dance dates from November 23, 1896 (diary entries). In January 1897 he wrote that he wanted to write "a healthy and cheeky comedy" in the open air. The original title was Liebesreigen , but Alfred Kerr Schnitzler recommended that it be changed. Schnitzler noted: "All winter I wrote nothing but a series of scenes that is completely unprintable, doesn't mean much in literary terms, but would be unearthed after a few hundred years and would illuminate a part of our culture in a peculiar way." (To Olga Waissnix , February 26, 1897) The ten scenes were written down a year later, on November 24, 1897.

In 1900 Schnitzler had 200 copies printed privately for friends at his own expense and was aware of the scandalous nature of his play from the start. In the foreword he wrote that the appearance of the following scenes was temporarily ruled out because “stupidity and bad will are always nearby are". It was not until 1903 that the first public edition was published by Wiener Verlag (with book decorations by Berthold Löffler ), as Schnitzler's regular publisher S. Fischer did not want to publish the work in Germany for legal reasons. The book caused a wave of outrage and was called "mess" and "the well-known foetor judaicus (Jewish stink)".

On March 16, 1904, at the request of the Berlin public prosecutor's office, the book was banned in Germany and then also in Poland. Despite criticism and censorship, the book was distributed, it sold 40,000 times and became "a well-known unknown book". Immediately after the publication of the print version, and especially after the premiere in Berlin, numerous parodies of the dance were written. In 1921 an edition with illustrations by Stefan Eggeler came out. S. Fischer Verlag did not take over the book until 1931, from its 101st edition.

"Original version"

No drafts or preliminary studies of the piece have survived in the storage locations of Schnitzler's estate, the Cambridge University Library and the German Literature Archive in Marbach . The Bodmer Foundation in Geneva thus owns the only known original manuscript pages. These were published by Gabriella Rovagnati for the first time in 2004 as an "original version" and were published in 2004 as a copy with 26 facsimile sheets by S. Fischer Verlag . The reactions in the press were euphoric about the find, including Hans-Albrecht Koch in the FAZ , the Süddeutsche Zeitung and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung . Criticism was expressed by Peter-Michael Braunwarth, who proved the editor to have serious reading errors solely on the basis of the published facsimile pages, including "confused" instead of "enthusiastic" or "strolled" instead of "strawanzt"; Doctor Angler ”.

Performance history

There was a German-language partial performance of scenes 4 to 6 on June 25, 1903 in the Kaim-Saal in Munich by the Academic-Dramatic Association (which was subsequently dissolved by the Bavarian Minister of Culture) and in the same year a cabaret performance that Schnitzler had not approved The eleven executioners in Munich. In November 1903 Hermann Bahr wanted to hold a public lecture in the Bösendorfersaal in Vienna, but this was banned by the police. A lecture by Marcell Salzer on November 21, 1903 in Breslau was successful and had no negative consequences. However, the current regulations of moral censorship in the Austrian Empire blocked the work's way onto the stage after Schnitzler had already come into conflict with censorship with his novella Leutnant Gustl (1900) and his drama Professor Bernhardi (1913).

On October 12, 1912, the piece was performed - unauthorized - in Budapest in Hungarian for the first time.

It was not until after the First World War that Max Reinhardt Schnitzler asked for the premiere rights in 1919: “I consider the performance of your work not only artistically opportune, but also absolutely desirable. However, it is a prerequisite that, given the dangers inherent in the objectivity of the material, the work does not fall into inartistic and undelicate hands, which could deliver it to the sensationalism of an overly prepared audience. ”(Max Reinhardt to Schnitzler, April 14, 1919 ) Reinhardt planned the world premiere under his own direction at the Großes Schauspielhaus in Berlin for January 31, 1920. For this purpose, he prepared a director's book that has been handed down and on which pages 1 to 48 contain instructions and revisions. The remaining pages, from 49–254, contain only a few notes. The reason for the termination of the work was that Reinhardt handed over his management to Felix Hollaender , the rights to the director of the small theater, Gertrud Eysoldt . The theater directors Josef Jarno , Emil Geyer and Alfred Bernau were also interested in the performance of the play.

Berlin 1920

The actual premiere took place on December 23, 1920 at the Kleiner Schauspielhaus in Berlin (in the building of the Academic University of Music in Berlin-Charlottenburg ) under the direction of Hubert Reusch, with Else Bäck (prostitute), Fritz Kampers (soldier), Vera Skidelsky (Chambermaid), Curt Goetz (young man), Magda Mohr (young woman), Victor Schwanneke (husband), Poldi Müller (sweet girl), Karl Ettlinger (poet), Blanche Dergan (actress), Robert Forster-Larrinaga (count) . A few hours before the Berlin premiere, the Prussian Ministry of Culture banned the performance at the request of the university (director: Franz Schreker ) and threatened the directors with six weeks' imprisonment. Gertrud Eysoldt stepped in front of the curtain, reported the situation to the audience and courageously declared that the impending prison sentence could not prevent her from standing up for the freedom of art and countering the accusation that Schnitzler was an “immoral writer”. The premiere took place regularly. On January 3, 1921, a court lifted the ban after the judges viewed the performance for themselves, calling the performance a "moral act" in their judgment.

Performances soon followed in other cities such as Hamburg ( Kammerspiele under Erich Ziegel , December 31, 1920), Leipzig (Kleines Theater), Hanover (September 1921), Frankfurt, Königsberg and Paris (Henri Bidon called the play a "masterpiece") and Norway, mostly without problems. At the Munich Schauspielhaus (after an incident on February 5, 1921) the performance was banned, as was the case in the USA (1923), Budapest (1926) and Teplitz (1928).

The critic Alfred Kerr wrote: “Schnitzler is more moody than fauny . With a thoughtful smile he gives the earthly humor of the subterranean world "and in his review of December 24, 1920 in the newspaper Der Tag asked the question:

“Can you forbid pieces? - Not even if they are badly written and badly played. But here is a lovely work - and it is played acceptably. The success was good; the audience didn't get any worse. And the world isn't a kindergarten, damn it. [...] Take a moment to rest and reflect! In the long run it becomes too boring to pretend to be dead from all the most important circumstances accompanying human reproduction; to act stupid. Long-term hypnosis. The classification of 'ancient times', 'medieval times', 'modern times' is basically premature. Dance is called love dance here. And love here does not mean platonic, but ... So: applied love. It is used without coarse, lustful or greasy things between ten pairs of people. And between all social classes. Always reaching over from one layer to another. Voltaire showed something similar in the " Candide ". The order for him is: housemaid; Franciscan; old countess; Rittmeister; Marquise; Page; Jesuit; Sailor of Columbus ... Here too, at least some of the bridging of class differences, which is so often sought, has been carried out. The psychic tragic comedy of the physical event was immortalized by the heavenly Hogarth in two pictures: named “Before” and “After”. The world still stands. Not filthy things: but aspects of life. Also the ephemeral nature of the tumult; the comical cloudiness of the disappearance of deception. Everything breathed in a quiet, funny charm. "

On February 22, 1921, riots broke out in Berlin after a high-ranking officer in the Berlin police had initiated systematic agitation against the performances. Many organizations were made to protest against the performance of the dance , pre-printed forms were sent out and politicians were mobilized. On February 22nd (a few days after the protests in Vienna) there was organized tumult in the performance and a hooting hall battle. Dedicated ethnic observers, most of them adolescent, threw stink bombs . Theater directors and actors were subsequently brought to court for "indecent acts" in the so-called Reigen trial (see below).

Vienna 1921

On February 1, 1921, the play had its premiere in Vienna in the Kammerspiele affiliated with the German People's Theater (director: Heinz Schulbaur). Various newspapers, especially the Reichspost , started an aggressive anti-Semitic smear campaign, Schnitzler was called a "pornographer" and a "Jewish pig literary", his play was called "Schandstück", "hottest pornography", and "Brothel prologue of the Jew Schnitzler". The journalist and writer Julius Bauer wrote a paraphrase of Goethe's last verses from Faust II in the ball book of the German-Austrian writers' cooperative Concordia : “The poet writes the indescribable. The eternal body goes a hundred times. The prudish and fearful, only damn the scribblers! Schnitzler sublimates everything that is catchy. "

“With the 'Reigen', Schnitzler turned the theater, which was supposed to be a house of joys, into a house of joy, the scene of events and conversations that cannot be more shamelessly unwound in a prostitute's den. Puffing thick pansies with their feminine appendages, which desecrate the name of the German woman, should now every evening let their nerves, slackened in the wild sensual frenzy, be tickled. But we remember to spoil the gentlemen the pleasure soon. "

At the performance on February 7th (two days after an incident at the Munich Schauspielhaus) there were initial disruptions, some young demonstrators stormed the performance and shouted “Down with the dance!” And “Man desecrates our women!”, The performance had to go the penultimate scene can be canceled. The Christian Social Member and later Chancellor Ignaz Seipel spoke on February 13 at a meeting of the Volksbund der Katholiken Österreichs of the play as a "piece of dirt from the pen of a Jewish author". On February 16, at the 4th scene (between a young man and a young woman), spectators threw stink bombs and gave a signal call outside. Around 600 demonstrators, including many young people, stormed the house with loud shouts of hurray and swinging sticks, smashed the mirror glass panes, penetrated the parquet and the boxes, from where they threw chairs and tar eggs at the audience. Schnitzler happened to visit the performance, but was not recognized by the mob of self-appointed moral guards and anti-Semites . The stage workers put an end to the tumult by using the fire hoses.

“Wednesday, February 16, the second storm took place, this time with resounding success. The sow performance had started at 7 o'clock. At about half past eight [...] a crowd that was growing minute by minute gathered. A few minutes after three quarters of eight o'clock in the meat market, some Volksstürmlern gave the signal to the storm. […] Volksstürmler ahead, a few hundred penetrated into the auditorium, where everything that was possible, panes of glass, chairs, etc., was smashed and the people present were thrashed with human pigs, sliders and prostitutes. Many were beaten bloody and had to be carried out. The theater was flooded by opening the hydrants, so that the fire brigade had to move in to pump out the hall. The fleeing Jewish spectators literally had to run the gauntlet (most of them without overalls), both inside and in the street, where a tremendous crowd demonstrated. Many were brought down on the stairs. The stage and many of the clean audience were pelted with dirt. "

After these incidents, the Viennese police chief Johann Schober banned any further performance in order to “protect public peace and order”. There were also fights in the Vienna Parliament; Social Democrats and Christian Socials got into each other's hair over the allegedly "obscene" play. Leopold Kunschak described the work as a "pig piece". This led to a controversy between the Interior Minister Egon Glanz and the Mayor of Vienna Jakob Reumann , who opposed a performance ban, and which was then decided by the Constitutional Court with the independent expert Hans Kelsen . In March 1922 the dance was resumed and played under police protection. The last performance took place on June 30, 1922. After the Viennese scandal, Karl Kraus stated in the torch : "In erotic theater, one and the same pack of people creates indignation and comfort."

In 1922 Schnitzler wrote resignedly, “Of the numerous affairs in my life, it is probably this last one in which mendacity, ignorance and cowardice have surpassed themselves”, and noted in his diary: “What a game of mendacity. Politicum. Insincere enemy and friend. -. Alone, alone, "He asked because of the polemic against alone round the S. Fischer Verlag , who owned the rights, no further performances of the play more to approve. This performance ban was extended by Schnitzler's son Heinrich after the author's death and remained in force until January 1, 1982.

Released in 1982

With the release of the dance dance at the theater, the Schnitzler reception reached a high point in the early 1980s. From 1982 there were numerous performances of the play, whereby the interest of the theaters of the scandal story was just as important as the challenge of the portrayal of sexuality and the nudity that it caused on stage. On New Year's Eve 1981/82, performances took place in Basel (January 1, 1982 at 12:25 a.m.), Munich, Manchester and London. As a result, there were performances on almost all German-speaking stages, including a. at the

- Residenztheater Munich (director: Kurt Meisel ), with Gundi Ellert (prostitute), Nikolaus Paryla (soldier), Lena Stolze ( housemaid ), Herbert Rhom (young man), Gaby Dohm (young woman), Kurt Meisel (husband), Bettina Redlich (Sweet girl), Walter Schmidinger (poet), Ursula Lingen (actress), Hans Brenner (count)

- Schillertheater Berlin (director: Hansjörg Utzerath ), with Sabine Sinjen (prostitute), Georg Corten (soldier), Gudrun Gabriel (housemaid), Andreas Bissmeier (young man), Mona Seefried (young woman), Peter Matić (husband), Marie Colbin (Sweet girl), Helmut Berger (poet), Senta Berger (actress), Joachim Bliese (Count)

- Schauspiel Frankfurt (director: Horst Zankl ), with Almut Zilcher (housemaid), Paulus Manker (young man), Suzanne von Borsody (sweet girl), Sabine Andreas (actress)

- Akademietheater Wien (director: Erwin Axer ), with Ulrike Beimpold , Robert Meyer , Elisabeth Augustin , Georg Schuchter , Sylvia Lukan , Wolfgang Hübsch , Susanne Mitterer, Karlheinz Hackl , Annemarie Düringer , Peter Wolfsberger

On May 10th, 2009 the scene “Whore and Soldier” experienced a “virtual premiere” on the Internet platform Second Life .

The Reigen Trial

After the premiere in Berlin, the two directors of the Kleiner Schauspielhaus, Maximilian Sladek and Gertrud Eysoldt , the director Hubert Reusch and the actresses Elvira Bach, Fritz Kampers , Vera Skidelsky, Victor Schwanneke, Robert Forster-Larrinaga, Blanche Dergan, Tillo, Madeleine, Riess-Sulzer, Delius and Copony brought to justice for "causing public nuisance". The trial took place in Berlin from November 5 to 18, 1921. The defense was taken over by the lawyer and former social democratic minister Wolfgang Heine , who then published the shorthand minutes of the trial at Ernst Rowohlt's publishing house .

The witness Elise Gerken (member of the Volksbund for decency and good manners ) testified at the hearing:

"I have spoken to many people, older and younger, men and women, who had seen the play, and I found them to confirm the judgment I had gained from reading that even the most subtle representation of the actors is incapable of to soften the filth and meanness of the work and to strip it of its immorality. According to my impression, which I also found reinforced in the court presentation on Sunday, the act, the most intimate union of man and woman, is presented here ten times, in its crudest and meanest form, stripped of all the ethical moments, all the ideal moments, who otherwise elevate this intercourse between man and woman from the animal to the human. The women who prostitute themselves ten times in this play give themselves, e.g. Sometimes after a few minutes, to a man not even known by name, they offer themselves. The whole process is also particularly sharply characterized by the fact that after the act the man turns away almost every time in a cynical brutality from the woman who was willing to him and partly pushes her back - a sign that here of love or of there is no question of any emotional relationships! "

Other witnesses criticized a “glorification of adultery”, took offense at the “debate on the nervous disorders of the young man” and particularly criticized the fact that the young woman commits adultery on the same day and then sleeps with her husband (although this is not expressly stated in the text) and that the rhythm of the music reproduced "coitus movements" as the curtain fell.

After five days of negotiation, during which numerous respected literary scholars, theater people and journalists such as Alfred Kerr , Ludwig Fulda , Felix Hollaender , Georg Witkowski and Herbert Ihering were heard as experts, acquittals were made because the performance was in no way "obscene or offensive" . The actors had "exercised the utmost decency". In the grounds of the judgment it said:

“As the court found from the evidence, the play pursues a moral idea. The poet wants to point out how stale and wrong love life is. In the opinion of the court, he did not intend. To arouse lust. […] The language of the book is fine and light. The characters are drawn excellently with a few sharp lines. The dramatic entanglements are developed with psychological delicacy. The action is carried out in each picture until immediately before the cohabitation, which is indicated in the book by dashes. Then the action starts again, which outlines the effect of the sexual intoxication. The sexual adjacent dwelling itself is not described. It resigns completely, for the poet it is only a means to an end. "

The process met with a great response in literary and artistic circles, because it was not just a question of whether the "dance" was about art or immorality, but ultimately also about the political question of whether the state should make rules on art . When the trial ended in acquittal, an important precedent was set for the progressive theater of the 1920s.

“We know that a kiss, a hug, so to speak, occurs very often on stage as a symbolic substitute for the actual sexual act, and we have got used to accepting this as entirely permissible and as compatible with our artistic and moral principles. It would be impossible to enumerate all the scenes in which the poet actually understands a kiss to be something other than the kiss itself; it would be impossible to enumerate all those acts that relate to what immediately after the curtain falls in the sense of the play has to point out, and there are also an abundance of cases in which the curtain rises immediately after a love embrace has taken place between two people on the scene in the sense of the play ('It is the nightingale and not the lark'). Now either this is hurtful or it isn't hurtful. However, it cannot be seen why it should be hurtful in one case and not in the other, but in particular it is impossible to understand why it should stimulate sensuality or destroy morality when it is artistically less valuable than when it is a valuable act. [...] If the dance is an artistically inferior work, it should of course not be performed, precisely because it is artistically inferior, because it shares those other characteristics that you condemn in it with a hundred others. [...] All objections that are raised against the performance of the dance must be raised against a whole host of others. "

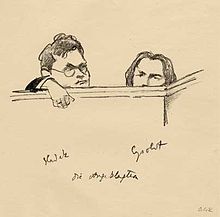

During the trial negotiations , Emil Orlik drew 14 lithographs from the Reigen Process in 1921 , which were printed in Berlin by Verlag Neue Kunsthandlung in 1921.

The broadcaster SWF produced a radio play documentary The Reigen Process - or: The Art of Taking Offense (Director: Fritz Schröder-Jahn ) with Willy Maertens (theater director Maximilian Sladek), Edith Heerdegen ( Gertrud Eysoldt ), Gustl Bayrhammer (actor Fritz Kampers ), Heinz Schimmelpfennig (actor Victor Schwanneke), Willy Trenk-Trebitsch ( Alfred Kerr ), Eric Schildkraut ( Emil Orlik ) a. a.

In 1967 Roger Vadim , director of the Reigen film adaptation La Ronde, was brought to court in Italy and even Arthur Schnitzler was charged posthumously.

Reception and interpretation

Schnitzler's friend Richard Beer-Hofmann described Reigen as Schnitzler's “most erect” work. Hugo von Hofmannsthal wrote to him: "After all, it is your best book, you dirt finch."

Egon Friedell wrote about Arthur Schnitzler in 1931: “He was already dramatizing psychoanalysis at a time when these doctrines were still emerging. And in his novels and plays he captured the Vienna of the fin de siecle and preserved it for later generations: a whole city with its unique culture, with the kind of people it nourished and developed, as it lived out at a certain point in time of maturity and over-maturity has become ringing and shining in them. He did something analogous to what Nestroy did for the Vienna of Vormärz . "

Georg Hensel describes Schnitzler's dialogues as "ten triumphs of sex, before which there are no class differences: a ring game of amours, who also have their delicacies, a carousel of fleeting hugs, a dance with the everlasting three steps: greed, pleasure and cold - a dance of death of Eros ”.

What takes the place of love in the dance "is not fatal, but poor, revocable death in small portions while still alive". The dialogues are frivolous and tender, ironic and melancholy, instinctual and saddened by death. Schnitzler's critical view of the sexual sphere of his time, which tabooed sexuality and tied it to the “sacred” institution of marriage, shows in the behavior of the people involved, especially that of the men. This is undermined by the double standards of the socially representative figures, who in their phrase-like speech reveal the unfree treatment of their own sexuality and manifests itself in the sexual exploitation of the maid and the “ sweet girl ” in the society around 1900, which was shaped by men get involved with "lower-ranking" women in order to ensure their masculinity. In the culture of the “ dump ” and the chambre separée as the scene of lies, deception and adultery, which continues into the marital bedroom, the narrowness and secrecy of the pleasure thought are evident. The people only characterize themselves by what they will say to the other partner or what they have said in the previous scene. Often only this shows that they are lying. Instead of naming the characters, Schnitzler uses a typology, the namelessness of the protagonists reveals their interchangeability in the sexual interplay. This sequence of figures paraphrases the medieval " dance of death " (representation of the violence of death over human life in allegorical groups in which dance and death can be found simultaneously).

Schnitzler's work makes it clear that the different moral concepts of the "culture" of the time were closely linked to the respective social class. Thus, throughout the play, morality is only addressed in those scenes in which the couple appear. A key role is played by the dialogue in the marriage bed, which clarifies the position of the young wife within the middle class. Only in the encounter between the poet and the actress (which Schnitzler himself and the actress Adele Sandrock could be copied) does a freer conception of sexuality emerge, and in the count's observations a philosophically reflective one.

Schnitzler describes the different sexual behaviors of the sexes before and after intercourse, but the separation of lust and love means that the relationships between man and woman run in an opposing emotional curve. The woman changes from brittle rejection to affectionate attachment, the man from romantic-sensual excitement to cold aversion. In the wake of their desire, people resemble each other despite social differences and ultimately become the same as representatives of the proletariat , petty bourgeoisie , bourgeoisie , bohemian and aristocracy regardless of social origin or age - as in the face of death.

The literary critic Richard Alewyn called the dance dance “a comedy for gods” and wrote in the epilogue to the book edition: “Dance dance - a masterpiece of the strict sentence. Ten people form his choreography. Ten times these ten people form a couple. The temperature rises ten times from zero to boiling point and then falls back to zero. Ten times the ups and downs of the scales of advertising, pairing, saturation and disenchantment, and in the end we are back to where it started and it is nothing but the mercy of the curtain that prevents the game from starting all over again . The only thing that cannot be found is how this piece could have been denounced as immoral. Far from whetting the appetite for amoureuse activity, it is much more likely to spoil it thoroughly. It is the work of a moralist , not an Epicurean , a work of exposure, of disenchantment, ruthless and deadly serious, and in comparison to this, the love affair still appears as a humane and comforting piece. ”( Richard Alewyn: Arthur Schnitzler: Reigen. Epilogue to Book edition 1960 )

Schnitzler dealt intensively with psychoanalysis and achieved in his work a far-reaching agreement with the psychological problems of his time, especially the depth psychological aspect of sexual behavior. Schnitzler is therefore often referred to as the literary counterpart to Sigmund Freud , who also emphasized this in a letter to Schnitzler in 1922: “Dear Doctor Schnitzler. For many years I have been aware of the far-reaching agreement ... So I got the impression that you know everything through intuition that I have uncovered in laborious work on other people. Yes, I believe that at heart you are a psychological in-depth researcher, as honest, impartial and fearless as anyone has ever been. But I also know that analysis is not a means of making yourself popular. Your devoted Dr. Freud. ”In a letter on the occasion of Schnitzler's sixtieth birthday, Freud even spoke of“ a kind of double aversion ”to him.

Film adaptations, radio plays and records

- 1950 La Ronde , directed by Max Ophüls , with Anton Walbrook (Adolf Wohlbrück) (emcee), Simone Signoret (prostitute), Serge Reggiani (soldier), Simone Simon (housemaid), Daniel Gélin (young man), Danielle Darrieux (young woman) ), Fernand Gravey (husband), Odette Joyeux (sweet girl), Jean-Louis Barrault (poet), Isa Miranda (actress), Gérard Philipe (count). Ophüls' famous film supplemented the plot with the figure of the conférencier (“Meneur de jeu”), who appears on a carousel (Ringelspiel) guides the viewer through Vienna around 1900, connects the scenes and also intervenes directly in the plot. In addition, there are parallel montages that show twice the future of a couple that is not a couple: the husband waits in vain for the “sweet girl” in the Chambre Separée, while the “sweet girl” is already with the poet and the sweet girl waits in vain to the poet at the stage exit of the theater while he is devoting himself to the actress in the cloakroom. Oscar Straus composed for the film the dance waltz Rotates you in the dance in the old way , where he made the Sylphentanz La Damnation de Faust by Hector Berlioz paraphrased.

- 1964 La Ronde , directed by Roger Vadim , screenplay: Jean Anouilh , with Marie Dubois , Claude Giraud , Anna Karina , Jean-Claude Brialy , Jane Fonda , Maurice Ronet , Catherine Spaak , Bernard Noël , Francine Bergé , Jean Sorel , Denise Benoît ( Yvette Guilbert ) (nominated for the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film). Screenwriter Jean Anouilh moved the location of the play to Paris. “The remake is endowed with noticeable irony, but largely lacks atmospheric appeal. Instead, the director relies more on the charms of his actresses. "(Lexicon of international films)

- 1966 Reigen (record recording) Director: Gustav Manker , with Hilde Sochor (prostitute), Helmut Qualtinger (soldier), Elfriede Ott (chambermaid), Peter Weck (young man), Eva Kerbler (young woman), Hans Jaray (husband) , Christiane Hörbiger (sweet girl), Helmuth Lohner (poet), Blanche Aubry (actress), Robert Lindner (count) (CD: Preiser Records 93124, 1988). With the record, the author succeeded in circumventing the play's ban on stage performance.

- 1973 Reigen , director: Otto Schenk , music: Francis Lai , with Gertraud Jesserer , Hans Brenner , Sydne Rome , Helmut Berger , Senta Berger , Peter Weck , Maria Schneider , Michael Heltau , Erika Pluhar , Helmuth Lohner .

- 1981 Reigen (radio play) Director: Peter M. Preissler . Production: BR. with Brigitte Neumeister (prostitute), Herwig Seeböck (soldier), Maresa Hörbiger (chambermaid), Klaus Maria Brandauer (young man), Johanna Matz (young woman), Albert Rueprecht (husband), Marianne Nentwich (sweet girl), Karl Maldek ( Poet), Lotte Ledl (actress), Wolfgang Gasser (count), Franz Hofer-Lester (speaker).

- 1982 Reigen (Ringlek) Sweden (TV). Director: Christian Lund, with Micha Gabay, Lars Green, Carl-Axel Heiknert, Christina Indrenius-Zalewski, Margaretha Krook .

- 2006 Berliner Reigen , directed by Dieter Berner , with Jana Klinge , Robert Gwisdek , Sebastian Stielke , Nina Machalz, Johanna Geißler, Dirk Talaga a. a. The action was moved to today's Berlin.

- 2011 radio play edition : Fräulein Else / Liebelei / Spiel im Dawn / Reigen u. a. Directed by John Olden . Production: NDR (radio play, 1963) with Helli Servi (prostitute), Wolfgang Gasser (soldier), Lotte Ledl (chambermaid), Peter Weck (young man), Christiane Hörbiger (young woman), Fred Liewehr (husband), Elfriede Ott ( Sweet girl), Helmuth Lohner (poet), Susi Nicoletti (actress), Wolf Albach-Retty (Graf), Hörverlag 2011, ISBN 978-3-86717-750-4

Adaptations

Movies

- 1944 La Farandole (France) directed by André Zwobada. Screenplay: André Cayatte and Henri Jeanson, with Alfred Adam, André Alerme, Jean-Louis Allibert, Bernard Blier , Jean Davy

- 1963 The big love game (And so to bed) (Austria / FRG). Director: Alfred Weidenmann . Script: Herbert Reinecker , Carl Merz , Helmut Qualtinger , with Hildegard Knef , Lilli Palmer , Nadja Tiller , Daliah Lavi , Thomas Fritsch , Walter Giller , Martin Held , Charles Regnier , Peter van Eyck , Paul Hubschmid , Elisabeth Flickenschildt . Starkino with twelve love episodes based on the example of the dance with the couples policeman / call girl, call girl / pupil, pupil / young wife of the school principal, director / secretary, secretary / boss, divorced wife of the boss / student, student / French, French / guest worker, Foreign worker / actress, actress / diplomat, diplomat / elderly lady, diplomat / call girl.

- 1965 Das Liebeskarussell (Austria) directed by Axel von Ambesser , Rolf Thiele and Alfred Weidenmann , with Nadja Tiller , Catherine Deneuve , Anita Ekberg , Johanna von Koczian , Heinz Rühmann , Gert Fröbe , Curd Jürgens and Peter Alexander . Episodic trivial version.

- 1971 Hot Circuit (Director: Richard Lerner ), based on Reigen

- 1973 Reigen , (FRG) Director: Otto Schenk.

- 1981 Neonstadt (FRG) Director: Gisela Weilemann , Helmer von Lützelburg , Dominik Graf , Johann Schmid / Stefan Wood, Wolfgang Büld . Five episodes about the attitude towards life and the problems of urban youth in the 1980s, inspired by Schnitzler's round dance .

- 1982 La Ronde (Director: Kenneth Ives), based on Reigen

- 1983 New York Nights (USA) Director: Simon Nuchtern, with Willem Dafoe , Nicholas Cortland, Corinne Alphen, George Ayer, Bob Burns, Peter Matthey, Missy O'Shea. Adaptation of Max Ophüls' film La Ronde in 9 episodes

- 1984 Choose Me (directed by Alan Rudolph ), with Geneviève Bujold , Keith Carradine , Lesley Ann Warren . The film practically transplanted Max Ophüls' Schnitzler adaptation La Ronde into contemporary Los Angeles.

- 1985 Love Circles (Ronde de L'Amour) (Great Britain) Director: Gérard Kikoïne , with Lisa Allison, Sophie Berger, Josephine J. Jones, John Sibbit, Michele Siu

- 1985 La ronde de l'amour (Love Circles) (director: Gérard Kikoïne), variation on Schnitzler's round dance .

- 1986 Das weite Land (director: Luc Bondy , co-author: Botho Strauss ) The film adaptation of Schnitzler's play Das weite Land invents new locations such as the theater and its dressing rooms, the actress, Ms. Meinhold (played by Jutta Lampe ) is in the world premiere to see von Reigen as a prostitute. Her son Otto is furious about this "scandalous play" in which his mother plays.

- 1992 Chain of Desire (USA). Directed by Temístocles López, with Linda Fiorentino , Elias Koteas , Patrick Bauchau , Malcolm McDowell

- 1997 The Way We Are (Quiet Days in Hollywood ) (USA / BRD) Director: Josef Rusnak , with Hilary Swank , Daryl Mitchell , Meta Golding , Natasha Gregson Wagner , Jake Busey . A “ reference” to Schnitzler's dance series transposed “into the X generation ” of Los Angeles

- 1998 Karrusel (10-part TV series, Denmark), directed by Claus Bjerre

- 2002 Love in the Time of Money , directed by Peter Mattei

- 2004 Seduction by Jack Heifner (Gay version)

- 2004 Complications by Michael Kearns (Gay version), pro-safe-sex piece (a remake was Dean Howell's film Nine Lives )

- 2008 Innschuld , directed by Andreas Morell , with Nadeshda Brennicke , Kai Wiesinger , Leslie Malton . With the adaptation by Kai Hafemeister , the film brought the parable into the 21st century.

- 2011 360 by Fernando Meirelles , screenplay: Peter Morgan , with Rachel Weisz , Jude Law , Anthony Hopkins , Moritz Bleibtreu and Johannes Krisch

- 2013 Deseo by Antonio Zavala Kugler from 2013

- 2016 Karussell (experimental film, Austria) by Gerda Leopold

The film Der Reigen (A career) by Richard Oswald (1920) has nothing to do with Schnitzler's original, despite having the same name and temporal proximity, which the latter also had to confirm in press releases.

Dramas and parodies

- 1921 The rose-red dance . Parody. First performance March 26, 1921 in the Theater in der Josefstadt .

- 1951 Reigen 51 by Helmut Qualtinger , Michael Kehlmann , Carl Merz , music: Gerhard Bronner (premier at Kleines Theater im Konzerthaus, Vienna) Cabaret parody.

- 1955 Reigen Express from Helmut Qualtinger . Radio play for the station " Rot-Weiß-Rot ".

- 1986 Round 2 by Eric Bentley (Gay version), set on the gay scene in New York in the 1970s

- 1994 Round process made in Germany , dramatic collage from real life by Frank Jankowski

- 1995 The lovely round dance after the round dance by lovely Mr Arthur Schnitzler by Werner Schwab (premier at the Schauspielhaus Zurich as a private event due to copyright problems). The people involved at Schwab are a whore, employee, hairdresser, landlord, young woman, husband, secretary, poet, actress, member of the National Council. Based on Schnitzler's piece “Werner Schwab designed his own version on the subject of“ sexuality ”. A world of sex without the inkling of eros, the world as a sex shop, garish, fast and icy-cold. Any feeling degenerates into a cliché, the individual asserts itself and is nevertheless interchangeable. "(Also TV, with Karina Fallenstein , Jessica Früh, Jutta Masurath, Katharina von Bock)

- 1998 The Blue Room by David Hare , UA Donmar Warehouse, London, directed by Sam Mendes , with Nicole Kidman and Iain Glen . The piece is moved to today's London, "the situations are updated, the characters pointed and the language vulgarized".

- Hilary Fannin; Stephen Greenhorn; Abi Morgan ; Mark Ravenhill : Sleeping Around (1998) - Rowohlt Theater Verlag 1999, translation by Corinna Brocher and Dieter Giesing

- 2005 Ringel-Ringel Reigen. Parodies of Arthur Schnitzler's round dance (Eds. Gerd K. Schneider, Peter Michael Braunwart). Special number, Vienna 2005. 12 parodies, most of which are in the tradition of the Wiener Volksstück and Nestroy .

Music theater and ballet

- La Ronde . Ballet by Erich Wolfgang Korngold . Performance: 1987, National Ballet of Canada, O'Keefe Center, Toronto; also: 1993 for The Royal Ballet, London

- 1951 Ronde de Printemps. Ballet. Choreography: Antony Tudor , music: Eric Satie . Resident Company, Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival, Lee, Massachusetts

- 1955 souvenirs. Ballet. Choreography: Tatjana SGsovsky, music: Jacques Offenbach / Simon Karlinsky. Berlin Ballet, Titania Palace , Berlin

- 1963 episodes. Ballet. Choreography: Gerhard Senft, interludes to music from the Strauss dynasty / Walter Deutsch. The Little Vienna Ballet, theater in the Josefstadt

- 1988 Arthur Schnitzler and his dance. Ballet in 9 pictures. World premiere at the Vienna Volksoper ( Wiener Festwochen ). Choreography: Susanne Kirnbauer. Music: Oscar Straus , Ernst von Dohnányi , Richard Heuberger , Josef Hellmesberger (son), Johann Strauss (son) , Alfred Grünfeld ( Herbert Mogg )

- 1993 Hello Again , musical, book and music: Michael John LaChiusa (German premiere 2007 at the Akademietheater in the Prinzregententheater Munich). The adaptation places the scenes in a decade of the 20th century.

- 1993 Reigen , opera in 10 dialogues by Philippe Boesmans , libretto by Luc Bondy ( Premiere Théâtre de la Monnaie , Brussels 1993; German premiere at the Staatstheater Braunschweig 1998)

- 2008 Fucking Men . Ballet by Joe DiPietro (Gay version), set in what is now New York.

- 2009 naked. Rock musical by Brandon Ethridge (premiere 2009 at the Bremen Musical Theater, director: Christian von Götz) Only Schnitzler's figure system is used, the original text is not spoken, there are "hot sex scenes, brutal bondage games and a rape, accompanied by loud punk rock" before and updates: the wife is constantly cleaning and frustrated eating, the son smokes and smears the walls, the married man rapes the schoolgirl, who then kills him with a wooden slat.

- 2011 La Ronde. Musical (gay version) by Peter Scott-Presland, music: David Harrod (UA Rosemary Branch Theater London).

- 2012 Re: igen . Opera by Bernhard Lang , libretto by Michael Sturminger (premiered at the Schwetzinger Festival 2014).

- 2018 the round dance. Musical. Book and music by Dean Wilmington. World premiere at the Theater an der Rott, Eggenfelden, November 16, 2018.

expenditure

- Round dance. Ten dialogues. Winter 1896/97. Printed as a manuscript. Buchdruckerei Roitzsch vorm. Otto Noack & Co. [1900] (private print)

-

Round dance. Ten dialogues. Wiener Verlag, Vienna and Leipzig 1903. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive ) (first edition)

- Reprint: round dance . Ten dialogues. Vienna and Leipzig 1903, dtv, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 978-3-423-02657-4 .

- Round dance / love affair . 2 plays, with a foreword by Günther Rühle and an afterword by Richard Alewyn . 38th edition, Fischer 2010 (reprint of the 1960 edition), ISBN 978-3-596-27009-5 ( Fischer Taschenbücher . Theater, Film, Funk, Fernsehen Volume 7009).

- A dance of love. The original version of "Reigens" . Edited by Gabriella Rovagnati. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-10-073561-7 .

- Round dance . Comedy in ten dialogues, epilogue by publisher Hansgeorg Schmidt-Bergmann . Insel, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 978-3-458-34520-6 .

- Round dance . Ten dialogues, Reclam 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-018158-4 .

- Round dance. Historical-critical edition. Edited by Marina Rauchbacher and Konstanze Fliedl with the collaboration of Ingo Börner, Teresa Klestorfer and Isabella Schwentner. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter 2019. (Arthur Schnitzler: Works in historical-critical editions, ed. Konstanze Fliedl) (Open Access: Volume 1 , Volume 2 )

literature

- Franz-Josef Deiters : Arthur Schnitzler: "Reigen". The allegorical immobilization of the moment . In: Drama at the moment of his fall. On the allegorization of drama in modern times. Attempt a constitution theory. E. Schmidt, Berlin 1999, pp. 83-117, ISBN 3-503-04921-5 .

- Ortrud Gutjahr (Ed.): Reigen by Arthur Schnitzler . Sexual scene and misconduct in Michael Thalheimer's production at the Thalia-Theater Hamburg , Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8260-4217-1 (= Theater and University in Conversation , Volume 10).

- Alfred Pfoser , Kristina Pfoser-Schweig, Gerhard Renner: Schnitzlers Reigen. Ten dialogues and their scandalous story. Analyzes and documents . 2 volumes. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-596-10894-2 and ISBN 3-596-10895-0 .

- Gerd K. Schneider: I want to see a bunch of falling stars rain down on you every day. On the artistic reception of Arthur Schnitzler's “Reigen” in Austria, Germany and the USA . Praesens, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-7069-0463-6 .

- Gerd K. Schneider: The reception of Arthur Schnitzler's Reigen, 1897–1994: Text, performances, film adaptations, press reviews and other contemporary comments , Ariadne Press, Riverside, CA 1995, ISBN 1-57241-006-X .

- Rania el Wardy: Play love - love while playing . Arthur Schnitzler and his metamorphosis of love for the game, Tectum, Marburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8288-9577-5 .

- Egon Schwarz : 1921 The staging of Artur Schnitzler's "Reigen" in Vienna creates a public uproar that draws involvement by the press, the police, the Viennese city administration, and the Austrian parliament. In: Sander L. Gilman , Jack Zipes (ed.): Yale companion to Jewish writing and thought in German culture 1096-1996. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1997, pp. 412-419

Web links

- Reigen (drama) in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

- First edition by Wiener Verlag as facsimile

- Piece text on projekt-gutenberg.org

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jenny Hoch: birds egg times ten. In: Spiegel Online. March 8, 2009, accessed May 4, 2019 .

- ↑ Lahan, B .: They loved each other and they fought: Arthur Schnitzler and Adele Sandrock. You crafty chimpanzee. Die Welt, Hamburg December 20, 1975. In: Lindken, H.-U .: Arthur Schnitzler. Aspects and accents. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Peter Lang GmbH 1987, p. 249

- ↑ (Zum) Riedhof (Johann Benedickter's Restaurant u. Weinhaldung) was a world-famous restaurant in Vienna 8. See, for example, a picture postcard ; see also Adolf Lorenz: I was allowed to help. My life and work. (Translated and edited by Lorenz from My Life and Work. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York) L. Staackmann Verlag, Leipzig 1936; 2nd edition ibid. 1937, p. 101 f.

- ↑ a b Hans Weigel: Reigen , Preiser Records 93124, 1964.

- ↑ a b Archived copy ( Memento from February 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ How the manuscript got into the Martin Bodmer collection is told: Lorenzo Belletini: On a winding path to the library of world literature , Neue Zürcher Zeitung, December 10, 2011

- ↑ Arthur Schnitzler: A love dance. The original version of the "Reigen". Published by Gabriella Rovagnati. Frankfurt / Main: S. Fischer 2004. Gabriella Rovagnati: How I came to the edition of the original round dance. In: Schnitzler's Hidden Manuscripts. Lorenzo Bellettini and Peter Hutchinson (eds.). Lang, Oxford, Bern, Berlin 2010. pp. 81-98.

- ^ Hans-Albrecht Koch: From tête-à-tête to duel . Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, June 24, 2004

- ^ Andreas Bernard in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, August 13, 2004.

- ↑ Jdl: Schnitzler love dance in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, August 7th of 2004.

- ↑ Peter Michael Braunwarth: Slipped for minutes or slipped continuously? Notes on a new Schnitzler edition. In: Hofmannsthal-Jahrbuch zur Europäische Moderne 13 (2005), pp. 295–300. A summary can be read: Konstanze Fliedl : The original version of the dance dance , PDF (last November 15, 2013)

- ↑ Kindly information from J. Green, Binghampton University ( The Max Reinhardt Archives & Library ), April 27, 2018. The director's book (“prompt book”) is today in the Reinhardt holdings in Binghampton. A copy can be found in the archive of the Salzburg Festival (formerly Max Reinhardt Research and Memorial Center). Images from the director's book are included in the Schnitzler / Reinhardt correspondence. (Schnitzler, Arthur and Max Reinhardt: Arthur Schnitzler's correspondence with Max Reinhardt and his colleagues , edited by Renate Wagner, Salzburg: Otto Müller 1971, after p. 88 (publication by the Max Reinhardt Research Center, II).)

- ↑ Nikolaj Beier, The anti-Semitic backgrounds of the Reigen scandal. in: First of all, I am me, 2008

- ↑ See decision 8/1921 of the findings and decisions of the Constitutional Court

- ^ Karl Kraus , Die Fackel , No. 561-567.

- ↑ End of self-censorship . In: Der Spiegel . No. 38 , 1981, pp. 266 ( online - Sept. 14, 1981 ).

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento from November 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The fight for the dance. Complete report on the six-day trial against the management and actors of the Kleiner Schauspielhaus Berlin. Edited and with an introduction by Wolfgang Heine, lawyer, former minister of state. D. Berlin: Ernst Rowohlt Verlag 1922.

- ↑ Minutes from the "Round Dance" process. 1921

- ^ W. Heine, Der Kampf um den Reigen , Berlin 1922, p. 429ff, quoted from: Kunstamt Kreuzberg (Hg) Weimarer Republik, Berlin-Hamburg 1977

- ↑ http://www.arthur-schnitzler.de/Hoerspiele%20alphabetische%20Liste.htm ( Memento from December 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Richard Beer-Hofmann to Arthur Schnitzler, [15. 2. 1903] In: Arthur Schnitzler: Correspondence with authors. Digital edition. Edited by Martin Anton Müller and Gerd Hermann Susen, [1] , accessed on August 7, 2020

- ^ Die Neue Rundschau , Volume 33, Part 1, S. Fischer, 1922

- ^ Georg Hensel, schedule. The actor guide from ancient times to the present.

- ↑ Rolf-Peter Janz, Reigen. in: Rolf-Peter Janz and Klaus Laermann, Arthur Schnitzler: On the diagnosis of the Viennese middle class in the fin de siècle. Metzler, Stuttgart 1977

- ↑ Erna Neuse: The function of motifs and stereotypical expressions in Schnitzler's round dance . In: Monthly books for German teaching, German language and literature 64 (1972).

- ↑ Schnitzler, Arthur: Reigen. Stuttgart: Reclam 2002. P. 141 f.

- ↑ Homepage of the film adaptation of Berliner Reigen ( Memento from December 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of February 27, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ stattgespraech.de ( Memento from February 12, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Shared echo on rock musical "Nackt". In: Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung. November 1, 2009, accessed May 4, 2019 .