Heinz Rühmann

Heinrich Wilhelm "Heinz" Rühmann (born March 7, 1902 in Essen ; † October 3, 1994 in Aufkirchen am Starnberger See ) was a German actor and director .

His role in the film Die Drei von der Gasstelle marked his breakthrough as a film actor in 1930. Since then he has been one of the most prominent and popular actors in German film and one of the best-paid film stars of the Nazi era . Rühmann was mainly used as an average comedic guy, as in his most famous role as Hans Pfeiffer in the comedy Die Feuerzangenbowle . In the post-war period he was able to build on earlier successes as a character actor, for example in Hauptmann von Köpenick and in Es happened in broad daylight . The actor had his last film appearance in 1993 in Wim Wenders ' In weiter Ferne, so nah! . In 1995, Heinz Rühmann was posthumously awarded the Golden Camera as the greatest German actor of the century .

Life

Childhood and youth

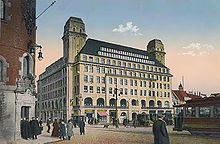

Heinz Rühmann was born in Essen in 1902. In the spring of the same year, his parents had leased the station restaurant in Wanne . Today the station forecourt as Heinz-Rühmann-Platz reminds of this connection. In front of the guests of the pub, Rühmann made his first appearances at the age of about five, which he himself described as the primal scenes of his career. In order to amuse his regulars, Hermann Rühmann regularly took his son out of bed in the evenings to have him recite poems on the counter. Heinz played his role as expected and enjoyed the applause from his audience. The business of the station restaurant developed very positively, so that in 1913 the Rühmanns were able to take over the newly opened Hotel Handelshof in Essen with cafés, restaurants, a wine salon and various shops. The economic success failed to materialize, so they had to file for bankruptcy at the end of the same year . As a result, their parents' marriage broke up and in March 1915 they divorced. Hermann Rühmann moved to Berlin , where he shortly afterwards probably suicide committed. The exact circumstances of death could never be clarified.

Ms. Rühmann and the children initially stayed in Essen. However, the family moved to Munich in 1916 because a friend had told their mother that this was the city with the lowest cost of living in Germany. However, it was also difficult in the Bavarian capital to support the three children with the narrow widow's pension. In the spring of 1919, Heinz Rühmann switched to the Luitpold-Oberrealschule to take his Abitur there. However, he followed the lessons listlessly. It was now his goal to become an actor. He joined a Munich amateur theater on Augustenstrasse . His mother supported him in his endeavors. In order to get to the professional level, he called on Ernst von Possart , who advised him against becoming an actor, but this did not irritate Rühmann. He turned to the actor Friedrich Basil from the court theater to get acting lessons. On the second attempt, Basil accepted it.

Early career

Richard Gortner became aware of him just six months later . Gortner, who ran two theaters in Breslau , including the Lobe Theater , offered Rühmann an engagement on both theaters for 80 marks a month. Basil, who saw the training in jeopardy, initially protested. He was finally convinced by his colleague that his protégé was in good hands in Wroclaw. Shortly before Rühmann was due to start his journey to his new job, he woke up in the morning with facial paralysis on his left side. A doctor diagnosed inflammation of the facial nerve as a result of a dragged on cold. Rühmann left anyway and was first sent home by his new employers to cure himself.

After a few weeks the paralysis disappeared and Rühmann made his first appearances. The hoped-for great success did not materialize in Wroclaw. His roles were too often designed for a manly, heroic guy. His relatively small height and boyish appearance contradicted this. Rühmann tried to compensate for the negative reviews by wearing eccentric clothing and a corresponding attitude in public.

After the actor had worked in Wroclaw for about a year, the director changed. Gortner left and was replaced by Paul Barnay . This took over the entire ensemble; the only exception was that Heinz Rühmann was not hired again due to a lack of talent. When the Residenztheater Hannover made him an offer in this situation , he accepted it immediately.

His obvious problem haunted him in his new job too. Rühmann was too small, too boyish to take on hero roles. While this awareness grew at Rühmann and he was considering how to deal with this difficulty, the Residenztheater closed its doors in 1922. The economic crisis prevailing at the time had deprived the theater of its economic basis. After a short return to Munich, Rühmann was able to find a new job in Bremen . Here he was offered the leading role in The Model Husband. It corresponded exactly to his personal charisma and was a great success for him. He played it well over 2,000 times over the next thirty years. In 1937 the film of the same name became a box-office hit. Contrary to what he himself portrays in his memoirs, The Model Husband was the most successful performance of the Bremen Schauspielhaus in 1922. In December of the same year, Rühmann terminated his contract because there had been difficulties with the management of the theater , which he himself had because of his sometimes quite violent improvisation was not innocent.

As a result, it was difficult to get a job due to the overall economic situation. Heinz Rühmann made unsuccessful attempts in Braunschweig and at the Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus . Finally, the Bavarian State Theater took him under contract. This was a touring theater without a permanent house. Founded in 1921 by the Bavarian Ministry of Culture , Otto Kustermann , who had made a name for himself as chief director at the Bremen theater , was in charge at the time . Kustermann had divided his actors into two groups who never saw each other because each group traveled to a different area. During his work Rühmann heard of an attractive woman, a member of the ensemble, who performed under the stage name Maria Herbot, but who was actually called Maria Bernheim (1897–1957). The two got to know each other, and Bernheim, over four years older and a good ten centimeters taller than Rühmann, gave up her actual job and became, as he called it himself, his private director.

Rühmann only stayed a few months at the Bayerische Landesbühne, then he received a call to the Munich Kammerspiele . The then director of the Kammerspiele, Hermine Körner , saw in him the essential enrichment of her ensemble in the comic field, and so he agreed. At this time, Heinz Rühmann got his first offer to work in a silent film. Basically not very enthusiastic about this medium, he was ultimately won over by the payment. A fee of 500 marks was promised for ten days of shooting. Rühmann accepted, and that's how he came to the screen in the film Das deutsche Mutterherz .

On August 9, 1924, Rühmann married Maria Bernheim. Instead of a wedding party, there was the premiere of slangs Die Adults , in which Rühmann had taken on one of the leading roles. When the mime was appointed to the Deutsches Theater in Berlin, the two saw each other less and less, which ultimately had an impact on the marriage.

Career as a film actor

At the end of the 1920s, Heinz Rühmann became a successful stage actor. The model husband still celebrated successes. He also got good reviews in the lead role as Charley's aunt . The first appearances in silent films followed. In 1930 Erich Pommer , at that time head of production at UFA , noticed him and invited him to audition for a sound film. Rühmann was not able to convince and was not hired. He worked tenaciously to get a second chance, which he eventually got. This time he played a disobedient student in an argument with his teacher. With this he convinced Pommer, who then gave him one of the leading roles in the film Die Drei von der Gasstelle , alongside Willy Fritsch and Oskar Karlweis . With gross sales of 4.3 million Reichsmarks , the film became the most successful film of the season. From then on, Rühmann was known throughout Germany.

Pommer was delighted with his new young actor. Even before Die Drei von der Gasstelle had its cinema premiere, Rühmann got another role in Burglar . He starred for the first time in his next film for UFA, The Man Who Is Looking for His Murderer (1931), and his fee doubled.

Secured economically in this way, Rühmann fulfilled a childhood dream. He got his pilot's license and bought his own plane . In 1932, the avid aviator made the acquaintance of Ernst Udet , who had become famous for his aerial battles during World War I. Rühmann admired Udet. He judged z. For example, his apartment on Salzburger Strasse in Berlin-Wilmersdorf was modeled on Udet's premises. In the “Fliegerzimmer” there were a number of photos that showed the two of them on excursions together.

Rühmann saw himself at the height of his career at that time and advertised sportswear. Ufa signed a long-term contract with him, which made him one of the best-paid actors in the German Reich at the time.

Career in the time of National Socialism

After the takeover of the NSDAP 1933 Rühmann expressed not publicly policy in Germany, in addition to the elimination of the rule of law and criminal arbitrariness the exclusion and persecution of Jews included. Rühmann was well acquainted with Joseph Goebbels and belonged to "a small circle around the Propaganda Minister".

When Rühmann got into trouble because his wife Maria Bernheim was viewed as Jewish and discriminated against, he turned to Goebbels. According to the Nuremberg Laws and similar regulations for artists in the Reichsfilmkammer, as the husband of a Jewish woman, Rühmann was placed on a "Jewish list" of the Reichsfilmkammer and was excluded from the chamber. That meant a professional ban. On November 6, 1936 Goebbels wrote in his diary: “Heinz Rühmann complains to us of his marital oath with a Jewish woman. I will help him. He deserves it because he is a really great actor. ”Rühmann was granted a special permit that enabled him to continue working as a film actor. But the problems continued. When Goebbels did not want to help him any further, Rühmann turned to Hermann Göring . He advised that he should get a divorce and that Bernheim should marry a foreigner, then she would have protection from persecution and Rühmann no more problems. The marriage with Maria Bernheim was divorced in 1938. Maria Bernheim married the Swedish actor Rolf von Nauckhoff , who lived permanently in Germany , "in a fictitious marriage" . Allegedly Rühmann Nauckhoff, who did not have a large income, “put a sports car in front of the door” for the wedding. The divorce later brought the charge that Rühmann had abandoned his wife in order to advance his acting career. But the couple had probably drifted apart before then. In any case, Maria Bernheim was present at Rühmann's wedding with Hertha Feiler in 1939. Bernheim was able to travel to Stockholm in 1943 and thus avoided the Holocaust . Rühmann received a foreign currency export permit that allowed him to continue supporting his ex-wife in Sweden with regular money transfers. In any case, Rühmann benefited from the divorce. On January 18, 1939, he regained his membership in the Reichsfilmkammer and no longer needed a special permit to work as an actor. His contacts with Goebbels and Göring paid off. In 1940 Rühmann took over the direction of a "birthday film" that the UFA made every year as a present for the Propaganda Minister. In it Rühmann showed the daily routine of the Goebbels children. According to the entry in his diary, Goebbels was very touched by the film.

In the mid-1930s, Heinz Rühmann had a long relationship with his colleague Leny Marenbach , who was his film partner in The Model Husband and Five Million Are Looking for an Heir , among others .

In 1938, Rühmann directed the film Lauter Lügen. Here he met the Viennese actress Hertha Feiler . The two married in July 1939. Hertha Feiler was classified as a “quarter Jew” according to the Nuremberg race laws , so that she had been able to marry Rühmann. With a special permit from Goebbels she was accepted into the Reichsfilmkammer. In 1942 their son Peter was born as the only child of the marriage .

Rühmann was not perceived by the film audience as a figurehead of the National Socialist regime. That was fully in line with Goebbels, who preferred subtle propaganda. The spectrum of Rühmann's film roles ranged from comical characters ( Die Feuerzangenbowle ) and tragicomic characters ( clothes make the man ) to propaganda appearances ( request concert ) . In Quax, the Bruchpilot , Rühmann played a "sincerely looking" aviator in a comedy film that was supposed to advertise military training. This is cited by Wolfgang Benz as an example of “indirect manipulative propaganda”. In 1941 he played under the direction of the President of the Reichsfilmkammer , Carl Froelich , in Der Gasmann, a gas reader who is suspected of foreign espionage. Like many prominent figures in the Third Reich, Rühmann enjoyed special payments, some of them annual, from a Hitler secret fund of between 20,000 and 60,000 Reichsmarks.

In connection with the invasion of Denmark and Norway by the Wehrmacht in the spring of 1940, the Rühmanns feared being abused as "mood makers". You wrote numerous letters to Danish friends to correct such an impression. When Heinz Rühmann was denounced to Goebbels that he wanted to emigrate with his wife, Goebbels had the case investigated by the head of the film department in the Reich Ministry for Propaganda and Public Enlightenment and later Reich film director Hippler . Goebbels noted in his diary on April 10, 1940: "Little things: Rühmann has declared himself positive." The main informer was also reprimanded.

In 1943, the film Die Feuerzangenbowle , which was being made, was banned from the performance of Nazi circles competing with Goebbels. a. the Minister of Education Bernhard Rust , because of the negative portrayal of the role of teachers. Thanks to Rühmann's good relationships with Hermann Göring, Rühmann was nevertheless able to get the film going in the cinemas. On Göring's orders he brought the film himself to the Fuehrer's headquarters in Wolfsschanze , where a private screening took place in Göring's presence, who thereupon ordered Hitler to lift the film ban. The film premiered on January 28, 1944.

Heinz Rühmann was not drafted into the Wehrmacht as a state actor . He only had to complete basic training as a defensive pilot at the Quarmbeck military training area south of Quedlinburg. For the regime he was more important as an actor than he could have been as a soldier. He was spared participating in the war effort. In August 1944 he was added to the regime's God- favored list.

Heinz Rühmann's country house villa in Berlin, Am Kleinen Wannsee 15, was bought very cheaply by Rühmann in 1938 from the widow of the late Jewish “department store king” Adolf Jandorf ( KaDeWe ), who fled the Nazis to The Hague . In doing so, he benefited from the persecution of the Jews. The villa was shot at in the course of the fighting for the Reich capital in March 1945 and burned down to the ground. The Rühmann-Feilers fled after their property was declared a main battle line (HKL). Nine moves to emergency shelters within Berlin followed by the end of the war on May 8, 1945.

Career in post-war Germany

In connection with the end of the war, Rühmann said in his autobiography that Russian officers had contacted him in May 1945 to talk “about the structure of German film”. In 2001 it became known that, like the physician Ferdinand Sauerbruch or the architect Hans Scharoun, he was also in an advisory relationship with the Ulbricht group . The very first edition of a German newspaper in the Soviet zone of occupation reported on Rühmann, who wished everyone involved in the reconstruction "joy and relaxation".

On March 28, 1946, as part of the so-called denazification , it was established that there were “no concerns about Mr. Rühmann's further artistic activity”. Until then, he was banned from performing. In July of the same year, Rühmann applied for permission to stage plays and traveled around with a small theater group.

Heinz Rühmann, drawing by Hans Pfannmüller , 1956

Heinz Rühmann, drawing by Günter Rittner , 1968

Rühmann founded the film company Comedia in the western sector in 1947 , which went bankrupt in 1953 after several failures . Only with the help of director Helmut Käutner did he make a comeback as an actor, first in the film Not Afraid of Big Animals (1953), then in the tragic comedy Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (1956), in which he played the shoemaker Wilhelm Voigt and for that in 1957 was awarded the German Film Critics' Prize. In the following years, Heinz Rühmann played in numerous entertainment films of varying quality and was able to build on his earlier successes.

Rühmann shot the Pater Brown adaptation The Black Sheep in 1960 and the sequel in 1962, He can't stop it . The director Helmuth Ashley remembered the commitment of the film composer Martin Böttcher , who set both films to music and also the Rühmann films Max, the pickpocket (1962) and The duck rings at ½ 8 (1968):

“… I noticed that a door was opening in the back (in the reception room). Heinz Rühmann crept in and sat in the back row. Without saying a word. After a quarter of an hour he disappeared. ... He wanted to make sure that he had made the right decision (to commit Böttcher) . "

In 1966 Rühmann received the Federal Cross of Merit .

Even after his early days, Rühmann continued to appear at the theater, B. at the Münchner Kammerspiele , where he was seen under the direction of Fritz Kortner in Waiting for Godot . From 1960 to 1962 Rühmann was a member of the Vienna Burgtheater . First he played there in My Friend Harvey at the Akademietheater , then he played Willy Loman in The Death of the Salesman . On December 31, 1976 Rühmann appeared as a frog in Die Fledermaus at the Vienna State Opera .

In 1970 his wife Hertha Feiler died of cancer in Munich. In 1974 Rühmann married his third wife on Sylt, the author and divorced publisher's wife Hertha Droemer (née Wohlgemuth, February 20, 1923 - April 20, 2016), whom he met at Siemens in the mid-1960s and contacted and contacted again for the first time in 1971 invited to an alpine sightseeing flight controlled by him.

From 1977 to 1982 he took part in the matinée Rund um die Oper in the Bavarian State Opera , to which the then director August Everding had invited him. As a representative of the audience, Rühmann explored all areas of the world of opera in this often scheduled and popular event. The conception of this matinee was developed with him by Klaus Schultz , who repeatedly engaged him to readings in the theaters in Aachen and Mannheim he directed from 1985 to 1993.

In the last years of his life, Rühmann discovered recitation as a new passion and more and more swapped the stage and screen for a recitation desk and record studio. In this context, his Christmas readings, which were shown on the Second German Television (ZDF), were particularly popular . a. 1984 in the St. Michaelis Church in Hamburg .

At Stars in the Manege 1980 Rühmann appeared with the clown Oleg Popow . When his colleague Edith Schultze-Westrum , with whom he had worked under Otto Falckenberg in the 1930s, died on March 20, 1981 , he gave the funeral speech at the burial at the Solln forest cemetery in Munich. In 1982 he published his autobiography under the title That was it .

On the occasion of his 90th birthday, a special program was broadcast on German television in 1992. Loriot and Evelyn Hamann performed a new sketch and then bowed to the “birthday boy”.

In 1993 he joined the RTL telecast Gottschalk Late Night on.

Heinz Rühmann made his last appearance on January 15, 1994 in Linz on the television show Wetten, dass ..? . The audience present celebrated the actor, who had already become a living legend, with tumultuous applause for several minutes and moved him to tears.

On October 3, 1994, Rühmann died in his house in Aufkirchen am Starnberger See at the age of 92 and was cremated a day later - at his request. The urn was buried on October 30, 1994 in Aufkirchen. The municipality of Berg , to which Aufkirchen belongs, renamed a street near which he last lived as Heinz-Rühmann-Weg . The community of Grünwald also has a Heinz-Rühmann-Strasse in the Geiselgasteig district not far from the Bavaria site.

Records

Rühmann has also made numerous records. His most famous was the sea shanty song That Can't Shake a Sailor , composed by Michael Jary and recorded on June 30, 1939. The film 5 million looking for an heir , which was released on April 1, 1938, also brought with it Ich break 'die Herz der Hochest Frau' n an evergreen . The song sung by Rühmann What is the street for? was one of the titles that were used in 1943 for the sound system at the Majdanek camp as part of the “ harvest festival ”. As on August 11, 1955, the film If the father with the son was released, the sung herein was lullaby La-Le-Lu (Our Song) famous. Newly arranged and underlaid with a contemporary rhythm, it entered the German single charts in November 1993.

pilot

Heinz Rühmann learned to fly privately with Eduard von Schleich , a former fighter pilot of the First World War, and received his flight license in 1930. He financed his first aircraft, a Kl 25 , from the fee of Die Drei von der Gasstelle . He was an exceptionally gifted pilot. When during the shooting of Quax, the Bruchpilot, the professional pilot made available due to a broken leg, and no replacement was available due to the war, Rühmann flew all scenes himself, including the aerobatic insoles. For reasons of age, he sold his machine at the age of 65, but soon bought a new one and flew until he was 80. Then he finally gave up his pilot's license.

Others

Heinz Rühmann's first automobile was a three-wheeled vehicle of the Diabolo brand , which was manufactured in Stuttgart and Bruchsal from 1922 to 1927.

Filmography

movie theater

presentation

- 1926: The German mother's heart (silent film)

- 1927: The girl with the five zeros (silent film)

- 1930: The three from the gas station

- 1930: burglar

- 1931: The man who is looking for his murderer

- 1931: Bombs on Monte Carlo

- 1931: My wife, the impostor

- 1931: The good sinner

- 1932: The pride of the 3rd company

- 1932: You don't need money

- 1932: It's getting better again

- 1932: Dashed the bill

- 1933: Me and the Empress

- 1933: laughing heirs

- 1933: Return to happiness

- 1933: Three blue boys - one blonde girl

- 1933: There is only one love

- 1934: The Grand Duke's finances

- 1934: What a bully

- 1934: Pipin the short one

- 1934: a waltz for you

- 1934: Heinz in the moon

- 1934: Frasquita

- 1935: Heaven on earth

- 1935: Who dares - wins

- 1935: Eva

- 1935: The outsider

- 1936: One shouldn't go to sleep without kissing

- 1936: Allotria

- 1936: If we were all angels

- 1936: Lumpacivagabundus

- 1937: The man they talk about

- 1937: The man who was Sherlock Holmes

- 1937: The model husband

- 1938: The detours of beautiful Karl

- 1938: Five million are looking for an heir

- 1938: 13 chairs

- 1938: Well, you don't know Korff yet?

- 1939: The Florentine hat

- 1939: Bachelor's Paradise

- 1939: Hurray! I am dad!

- 1940: Clothes make the man

- 1940: Request concert (vocal performance)

- 1941: The main thing is happy

- 1941: The gas man

- 1941: Quax, the break pilot

- 1942: Front theater ( cameo )

- 1943: I entrust you with my wife

- 1944: The Feuerzangenbowle

- 1945: tell the truth (unfinished)

- 1948: The gentleman from the other star

- 1949: The Red Cat's Secret

- 1949: I'll make you happy

- 1952: It can happen to anyone

- 1952: We'll rock the child

- 1953: Quax in Africa (completed 1944)

- 1953: Don't be afraid of big animals

- 1953: Postman Müller

- 1954: On the Reeperbahn at half past twelve

- 1955: Stopover in Paris (Escale à Orly)

- 1955: When the father with the son

- 1956: Charley's aunt

- 1956: The captain of Köpenick

- 1956: The Sunday Child

- 1957: In contrast, being a father is a lot

- 1958: It happened in broad daylight

- 1958: The man who couldn't say no

- 1958: The timpanist

- 1958: The iron Gustav

- 1959: people in the hotel

- 1959: A man walks through the wall

- 1960: The youth judge

- 1960: My school friend

- 1960: The good soldier Schwejk

- 1960: Father Brown - The Black Sheep

- 1961: The Liar

- 1962: Max, the pickpocket

- 1962: Father Brown - He can't stop

- 1963: my daughter and me

- 1963: The house in Montevideo

- 1964: Beware of Mister Dodd

- 1965: Dr. med. Job Praetorius

- 1965: The love carousel

- 1965: The Ship of Fools

- 1966: Hocus pocus or: How do I make my husband disappear ...?

- 1966: The Greek is looking for a Greek

- 1966: Money or Life (La bourse et la vie)

- 1966: Maigret and his greatest case

- 1968: The Adventures of Cardinal Braun (Operazione San Pietro)

- 1968: The duck rings at ½ 8

- 1971: The captain

- 1973: Oh Jonathan - oh Jonathan!

- 1977: The Chinese miracle

- 1977: Found eating

- 1993: Far away, so close!

production

- 1939: The Florentine hat

- 1939: Bachelor's Paradise

- 1940: Clothes make the man

- 1941: The main thing is happy

- 1941: Quax, the break pilot

- 1943: I entrust you with my wife

- 1944: The Feuerzangenbowle

- 1944: The angel with the strings

- 1945: Quax in Africa

- 1945: tell the truth (unfinished)

- 1948: The gentleman from the other star

- 1948: Berlin ballad

- 1949: The Red Cat's Secret

- 1949: Martina

- 1949: murder trial of Dr. Jordan

- 1949: I'll make you happy

- 1950: 12:15 a.m., room 9

- 1950: wonderful times

- 1951: Shadows over Naples

Director

- 1938: Lots of lies

- 1940: All love

- 1943: Sophienlund

- 1944: The angel with the strings

- 1948: The copper wedding

- 1953: Postman Müller

watch TV

presentation

- 1968: The Death of the Salesman (TV movie)

- 1969: Tell Santa Claus (TV movie)

- 1970: My friend Harvey (TV movie)

- 1970: Final spurt (TV movie)

- 1971: The Pawnbroker (TV movie)

- 1973: The Janitor (TV movie)

- 1976: No evening like any other (TV movie)

- 1978: Servants and other masters (TV movie)

- 1979: Another opera (TV movie)

- 1979: Balthasar in a traffic jam (TV movie)

- 1980: All good things come in threes (film) (TV film)

- 1981: A Train to Manhattan (TV Movie)

- 1983: There are still hazelnut bushes (TV movie)

Documentation (selection)

- 1972: Heinz Rühmann's 70th birthday. Portrait of an actor. Friedrich Luft talks to Rühmann about his life (Director: Heribert Wenk)

- 1982: actor, aviator, human. Hermann Leitner talks to Rühmann about his life. (Director: Hermann Leitner)

- 1994: Little man, big. (Director: Bernhard Springer)

- 2007: Heinz Rühmann - the actor. Part of the ZDF documentary series “Hitler's Useful Idols”. (Director: Michael Strauven)

- 2007: Legends - Heinz Rühmann. Part of the ARD documentary series " Legends ". (Director: Sebastian Dehnhardt )

Discography

music

- 1936: Li-li, Li-li, Li-li, love / What is the street for? (Odeon O-25 846)

- 1937: Yes, gentlemen! (Duet with Hans Albers) (Odeon O-25 919a)

- 1938: I break the hearts of the proudest women (Odeon O-26 126a)

- 1939: That can't shake a seaman (with Hans Brausewetter and Josef Sieber) / What is the road for? (Odeon O-26 342)

- 1940: Wanderlied / I'm fine ... (Duet with Hertha Feiler) (Odeon O-4629)

- 1940: I am so passionate! / I only do that with a nice smile (Odeon O-4632)

- 1955: When the father with the son (duet with Oliver Grimm) / What kind of fun club we men are (Odeon O-29010)

- 1957: O Bello / It won't stay that way (Polydor 23 565)

- 1975: I know / The Clown (Philips 6003 450)

- 1975: Meeting point heart: What is the street for ... (Duet with Peter Alexander on LP) (Ariola 89 370 XT)

- 1993: Our song (LaLeLu) remix by Cinematic feat. Heinz Rühmann and Oliver Grimm (Hansa 74321 14746 7)

- 1994: A good friend remix by Cinematic & Heinz Rühmann (Hansa 74321 19941 7)

also:

- It's good for an earthworm / Die Ballade vom Semmelblonden Emil (later edition as a vinyl single by EMI Electrola)

- A friend, a good friend (on various compilations, film sound)

word

- 1976: Heinz Rühmann tells Max and Moritz about Wilhelm Busch. (Poly / Polydor STEREO 2432 175)

- 1979: Dear Augustin. The story of an easy life. (Tudor 77029)

- 1982: Christmas with | Christmas with Heinz Rühmann. (Orfeo S 037821 B)

- 1984: Reineke Fuchs. From Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. (with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra) (Orfeo S 110 842 H)

- 1988: Heinz Rühmann tells Christmas stories by Felix Timmermans. (Deutsche Grammophon Literatur 427 278-1)

- 1989: The 13 months. Heinz Rühmann speaks Erich Kästner. (Deutsche Grammophon Literatur 429 418-1)

- 1992: Heinz Rühmann tells fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. (Deutsche Grammophon Literatur 435 890-1)

- 1992: Christmas with Heinz Rühmann. (Ariola 74321 11041 2)

- 1992: Heinz Rühmann reads the Sermon on the Mount. (Lipp 004)

- 2004: Waiting for Godot. (Bayerischer Rundfunk 1954) (Deutsche Grammophon Literatur. ISBN 978-3-82911-491-2 .)

- 2004: You can tell me a lot. (NWDR 1949) (Deutsche Grammophon Literatur. ISBN 978-3-82911-492-9 .)

- 2004: An angel named Schmitt. (NWDR 1953) (Deutsche Grammophon Literatur. ISBN 978-3-82911-493-6 .)

- 2004: Abdallah and his donkey. (Bayerischer Rundfunk 1953) (Deutsche Grammophon Literatur. ISBN 978-3-82911-494-3 .)

- 2004: The Feuerzangenbowle. A radio play using the famous film sound. (Deutsche Grammophon Literatur.)

Radio plays

- 1926: Die Lore (The Little One) (after Otto Erich Hartleben ) - Director: Albert Spenger , with Otto Framer , Albert Spenger, Ruth Giethen

- 1927: The Seventeen Year Olds (after Max Dreyer ) - Director: Rudolf Hoch , with Rudolf Hoch, Elise Aulinger , Ewis Borkmann, Ferdinand Classen

- 1949: You can tell me a lot (by Christian Bock ) (Johannes) - Director: Ulrich Erfurth

- 1952: Not only at Christmas time (based on Heinrich Böll ) - Director: Fritz Schröder-Jahn , with Reinhold Lütjohann , Thea Maria Lenz, Rudolf Fenner, Ingeborg Walther

- 1953: Abdallah and his donkey (after Käthe Olshausen ) (donkey) - Director: Hanns Cremer , with Axel von Ambesser , Bum Krüger , Alexander Malachovsky , Helen Vita , Heinz Leo Fischer

- 1953: An angel named Schmitt (after Just Scheu and Ernst Nebhut ) (Thomas Schmitt, Paul Gerlach's secretary) - Director: Otto Kurth , with Hans Zesch-Ballot , Gisela Peltzer , Helmut Peine , Jo Wegener , Charlotte Joeres

- 1954: Waiting for Godot (based on Samuel Beckett ) (tarragon) - Director: Fritz Kortner , with Friedrich Domin , Ernst Schröder , Rudolf Vogel

- 1955: My wife doesn't hear a word - Direction: Axel von Ambesser , Friedrich Luft , Jörg Jannings , with Hertha Feiler , Karl Schönböck , Eva Kerbler

Awards

- 1938: Venice International Film Festival : Medal (Acting Achievement) for The Model Husband

- 1940: Appointment as state actor

- 1940: Honorary membership of the Danish Aviation Club

- 1949: Venice International Film Festival : Special award (ingenious representation of post-war German conditions) for Berlin Ballad

- 1955: Honorary member of the International Artist Lodge

- 1957: Golden Gate Award (Best Actor) for Der Hauptmann von Köpenick

- 1957: Art Prize of the City of Berlin

- 1957: Film tape in gold (best leading actor) for Der Hauptmann von Köpenick

- 1959: Ernst Lubitsch Prize

- 1961: German Film Critics' Prize

- 1961: Federal Film Prize with the film tape in gold (Best Actor) for The Black Sheep

- 1962: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1963: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1964: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1966: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1966: Great Cross of Merit of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 1966: Silver screen for TV-Hören undsehen magazine

- 1967: Golden screen of TV-Hören undsehen magazine

- 1967: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1968: Golden screen of TV Hören undsehen magazine

- 1968: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1969: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1971: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1972: Large Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany with a star

- 1972: Filmband in gold for many years of outstanding work in German film

- 1972: Golden canvas (special award) for special merits

- 1972: Medal of Honor from the Central Organization of the Film Industry ( SPIO ) for life's work

- 1972: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1973: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1973: Golden screen of the Main Association of German Film Theaters

- 1977: Large Cross of Merit of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany with star and shoulder ribbon

- 1977: Cultural Prize of Honor from the City of Munich

- 1978: Golden Bambi as the most popular actor

- 1978: Chairman of the Association for the Promotion of the Münchner Kammerspiele e. V.

- 1979: Golden Camera from HÖR ZU magazine

- 1981: Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art

- 1981: Silver Medal at the 24th New York Film Festival for A Train to Manhattan

- 1982: Silver Chaplin stick from the Association of German Film Critics

- 1982: Gold Medal of Honor of the City of Munich

- 1984: Golden Bambi for his overall performance

- 1986: Bavarian Film Prize : Honorary Prize

- 1989: Appointment as professor honoris causa for art and science of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia

- 1990: Golden Berolina

- 1992: Otto from Magdeburg for the complete works

- 1995: Golden Camera in the category Greatest German Actor of the Century ( posthumous )

- 2002: Golden radio clock from the TV magazine Funk Uhr in the "The greatest TV and film stars of all time" election

- 2006: 1st place in the show Favorite Actors of the ZDF series Our Best

Autobiography

- That's it Memories. (= Ullstein. 20521). Ullstein, Berlin / Vienna / Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-550-06472-1 (14th edition 1995, ISBN 3-548-20521-6 ).

literature

- Georg A. Weth: Heinz Rühmann life recipes from an immortal optimist. Langen-Müller, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7844-2854-1 .

- Franz J. Görtz, Hans Sarkowicz: Heinz Rühmann 1902–1994. The actor and his century. Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-48163-9 .

- Torsten Körner : The little man as a star: Heinz Rühmann and his films of the 50s , with a foreword by Reinhard Baumgart . Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2001, ISBN 3-593-36754-8 (dissertation Humboldt University Berlin).

- Torsten Körner: A good friend: Heinz Rühmann. Structure, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-7466-1925-4 .

- Torsten Körner: Rühmann, Heinz Wilhelm Hermann. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 22, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11203-2 , pp. 219-221 ( digitized version ).

- Hans-Ulrich Prost: That was Heinz Rühmann. Bastei, Bergisch Gladbach 1994, ISBN 3-404-61329-5 .

- Fred Sellin: I break hearts ..., the life of Heinz Rühmann. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-498-06349-9 .

- Gregor Ball, Eberhard Spiess , Joe Hembus (eds.): Heinz Rühmann and his films. Citadel-Filmbücher , Goldmann, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-442-10213-8 .

- Hans Hellmut Kirst , Mathias Forster and others: The great Heinz Rühmann book. Naumann & Göbel / VEMAG, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-625-10529-2 .

- Michaela Krützen: "Group 1: Positive" Carl Zuckmayer's assessments of Hans Albers and Heinz Rühmann. In: Carl Zuckmayer yearbook. published by Günther Nickel, Carl-Zuckmayer-Gesellschaft . Wallstein, Göttingen 2002, ISSN 1434-7865 , pp. 179-227.

- Berndt Schulz : Heinz Rühmann. Moewig, Rastatt 1994, ISBN 3-8118-3924-1 (with numerous b / w photos and filmography).

- Hertha Rühmann: My years with Heinz , Langen Müller Verlag , 2004

Web links

- Heinz Rühmann in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Literature by and about Heinz Rühmann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Heinz Rühmann in the German Digital Library

- Heinz Rühmann at Discogs (English)

- Heinz Rühmann memorial page

- Do you know Heinz Rühmann ? Comprehensive information about Heinz Rühmann and his films

- The man who was Heinz Rühmann by Michael Wenk, epd film 03/2002

- Dietrich Kuhlbrodt : Rühmann, Stoiber and the No. 1: Hitler , book excerpt, filmzentrale.com, 2006

- Heinz Rühmann at filmportal.de

- Spiegel Online Dossier: 7 articles 1949–2002

Individual evidence

- ^ Franz J. Görtz, Hans Sarkowicz: Heinz Rühmann 1902–1994. The actor and his century. Munich 2001, p. 107.

- ↑ Anja Greulich, Guido Knopp: Heinz Rühmann. In: Guido Knopp (ed.): Hitler's useful idols. 1st edition. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-570-00835-5 , p. 19.

- ↑ Heinz Rühmann: That's it - memories. 1st edition. Ullstein Verlag, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / Vienna 1982, p. 23.

- ↑ Anja Greulich, Guido Knopp: Heinz Rühmann. In: Guido Knopp (ed.): Hitler's useful idols. 1st edition. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-570-00835-5 , p. 14 ff.

- ↑ Heinz Rühmann: That's it - memories. 1st edition. Ullstein Verlag, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / Vienna 1982, p. 24.

- ↑ Rühmann himself wrote about his teacher: “Friedrich Basil […] was an impressive figure in Munich's cultural life. He still embodied the court theater style with a rolling tongue-R. The writer Frank Wedekind also took acting lessons from him, and later I heard that he had instructed Adolf Hitler in gestures. Both of them would be able to do it. ”Cf. Heinz Rühmann: That's it - memories. 1st edition. Ullstein Verlag, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / Vienna 1982, p. 28.

- ↑ Anja Greulich, Guido Knopp: Heinz Rühmann. In: Guido Knopp (ed.): Hitler's useful idols. 1st edition. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-570-00835-5 , p. 22 f.

- ↑ Heinz Rühmann: That's it - memories. 1st edition. Ullstein Verlag, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / Vienna 1982, p. 41.

- ↑ Anja Greulich, Guido Knopp: Heinz Rühmann. In: Guido Knopp (ed.): Hitler's useful idols. 1st edition. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-570-00835-5 , p. 25 f.

- ↑ Heinz Rühmann: That's it - memories. 1st edition. Ullstein Verlag, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / Vienna 1982, p. 49.

- ↑ a b Anja Greulich, Guido Knopp: Heinz Rühmann. In: Guido Knopp (ed.): Hitler's useful idols. 1st edition. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-570-00835-5 , p. 26 f.

- ↑ Torsten Körner: A good friend: Heinz Rühmann. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-351-02525-4 , p. 334.

- ↑ Heinz Rühmann: That's it - memories. 1st edition. Ullstein Verlag, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / Vienna 1982, p. 54.

- ↑ Hans Josef Görtz, Hans Sarkowicz: Heinz Rühmann, 1902-1994: the actor and his century. 1st edition. Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-48163-9 , p. 55 ff.

- ↑ Heinz Rühmann and flying (The page is part of a larger website realized with a frame). He later owned a De Havilland "moth" .

- ↑ Anja Greulich, Guido Knopp: Heinz Rühmann. In: Guido Knopp (ed.): Hitler's useful idols. 1st edition. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-570-00835-5 , p. 14 ff.

- ^ Felix Moeller: The Film Minister - Goebbels and the cinema in the “Third Reich” . Edition Axel Melges, London 2000, ISBN 3-932565-10-X , p. 179.

- ^ A b c Franz Josef Görtz, Hans Sarkowicz: Heinz Rühmann, 1902–1994. The actor and his century. 2001, p. 192 ff.

- ↑ Klaudia Brunst: If we were all angels. In: TAZ , October 6, 1994, accessed on August 13, 2020 (obituary for Heinz Rühmann).

- ↑ Lutz Hachmeister , Michael Kloft (ed.): The Goebbels Experiment - Propaganda and Politics . DVA, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-421-05879-2 , p. 218.

- ^ Wolfgang Benz: On the role of propaganda in the National Socialist state. In: Hans Sarkowicz: Hitler's Artists - Culture in the Service of National Socialism . Insel, Frankfurt 2004, ISBN 3-458-17203-3 , p. 19.

- ^ Felix Möller: Film stars in propaganda use . In: Hans Sarkowicz: Hitler's Artists - Culture in the Service of National Socialism . Insel, Frankfurt 2004, ISBN 3-458-17203-3 , pp. 144 f.

- ↑ Torsten Körner: A good friend: Heinz Rühmann. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-7466-1925-4 , p. 209.

- ↑ Torsten Körner: A good friend: Heinz Rühmann. Construction Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-7466-1925-4 , p. 213.

- ^ Franz Josef Görtz, Hans Sarkowicz: Heinz Rühmann, 1902–1994. The actor and his century. 2001, p. 241 ff.

- ↑ There is also talk of Rechlin-Lärz . https://www.ndr.de/geschichte/rechlin126_page-2.html

- ^ Ernst Klee : The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-10-039326-5 , p. 502.

- ^ Franz Josef Görtz, Hans Sarkowicz: Heinz Rühmann. 1902-1994. Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-48163-9 , p. 197.

- ↑ Heinz Rühmann: That's it. Memories. Ullstein, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-548-20521-6 .

- ^ Franz Josef Görtz : The Heinz Rühmann file. The legendary comedian was one of Hitler's favorite actors - and later adviser to Walter Ulbricht before the GDR was founded. In: Fee-based archive of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung , October 14, 2001 (enter “Die Heinz Rühmann” under the search term).

- ↑ Berliner Zeitung of May 21, 1945, p. 2 (of 4)

- ↑ Torsten Körner: A good friend: Heinz Rühmann. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-7466-1925-4 , p. 276.

- ↑ In: Reiner Boller: Winnetou-Melodie - Martin-Böttcher-Biographie, ISBN 978-3-938109-16-8 .

- ↑ youtube.com

- ↑ For sale: Heinz Rühmann's villa in Berg . In: https://www.merkur.de/ . September 22, 2016 ( merkur.de [accessed November 6, 2017]).

- ↑ knerger.de: The grave of Heinz Rühmann .

- ^ Stefan Klemp : Action harvest festival. With music to death: reconstruction of a mass murder. Villa ten Hompel, Münster 2013 (= current. Volume 19), ISBN 978-3-935811-16-0 , p. 79.

- ↑ Cinematic feat. Heinz Rühmann & Oliver Grimm - Our Song (La Le Lu). officialcharts.de

- ↑ Stefan Bartmann: The unknown relative of the "Bruchpilot", Part 1: This side of Africa. In: Flugzeug Classic. No. 3/2013.

- ↑ Werner Oswald : German Cars 1920–1945. 10th edition. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-87943-519-7 , p. 439.

- ↑ Fred Sellin: I break hearts. The life of Heinz Rühmann. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 2001, p. 160.

- ↑ Discography on discogs.com .

- ↑ a b c d That's it (p. 309).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rühmann, Heinz |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Rühmann, Heinrich Wilhelm (full name); Rühmann, Heinrich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German actor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 7, 1902 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | eat |

| DATE OF DEATH | 3rd October 1994 |

| Place of death | Aufkirchen am Starnberger See |