Captain von Koepenick

Friedrich Wilhelm Voigt (* 13. February 1849 in Tilsit ; † 3. January 1922 in Luxembourg ) was from East Prussia originating shoemaker . He became known as Hauptmann von Köpenick through his spectacular occupation of the town hall of the city of Cöpenick near Berlin , which on October 16, 1906, disguised as a captain , he entered with a group of gullible soldiers , arrested the mayor and stole the city treasury .

This event, which met with great public interest and when the Köpenickiade entered the German language, was often artistically processed. Carl Zuckmayer's play Der Hauptmann von Köpenick is particularly well-known .

The historical Wilhelm Voigt

Career and history

Wilhelm Voigt was born on February 13, 1849 as the son of a shoemaker in Tilsit . At the age of 14 he was sentenced to 14 days in prison for theft . His years of traveling as a journeyman shoemaker took him through large parts of Pomerania and to Brandenburg . Between 1864 and 1891 he was convicted four times of theft and twice for forgery and spent many years in prison. The last time he tried to rob the court treasury in Wongrowitz in what was then the Prussian province of Posen with a crowbar in 1890 , he received a 15-year prison sentence . After his release early 1906 Voigt moved to Wismar , where it the institution clerics had given a journeyman point when Hofschuhmachermeister Hilbrecht where he led well. Due to his previous convictions, however, after a few months the police were banned from staying in the Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin .

He then moved to Rixdorf near Berlin, where he lived with his older sister Bertha and her husband, the bookbinder Menz, and found work in a shoe factory. On August 24, 1906, Wilhelm Voigt was also banned from staying in the greater Berlin area, which he did not adhere to. Instead, he moved as a sleeper to unannounced accommodation in Berlin-Friedrichshain near the Silesian train station . He initially kept his job, but due to his illegal status he had little prospect of permanent employment. At the end of September, he told his employer and his partner Riemer, a 50-year-old factory worker who lived in the sister's house next door, about an alleged inheritance in Odessa , which he would have to travel for some time to claim. The last time he appeared at the factory was on October 6th.

The Köpenickiade

For his coup, Voigt had put together the uniform of a captain of the Prussian 1st Guard Regiment on foot from parts purchased from various dealers . In this disguise he stopped a troop of guard fusiliers (so-called "cockchafer") on the street at noon on October 16, 1906 near the Plötzensee military bathing establishment in west Berlin at the time of the changing of the guard , and left a second troop of detached guards from the shooting range of the 4th Guard -Regiments summoned and placed ten or eleven men under his command, referring to a nonexistent cabinet order “on the highest orders”.

He drove with them on the Berlin tram to Koepenick , since, as he explained to the soldiers, it was not possible for him to “commandeer vehicles”. During a stop in Rummelsburg , he served the men with beer. Voigt himself approved a cognac for 25 pfennigs , according to Private Klapdohr . After arriving in Koepenick, he gave each soldier a mark and let them have lunch at the train station. He then told them that he would " arrest the mayor and perhaps other gentlemen."

They then marched to the town hall of the then still independent city. Voigt and his troops occupied the building, had all exits cordoned off and forbade the officials and visitors to the building “any traffic in the corridors”. He then arrested Upper City Secretary Rosenkranz and Mayor Georg Langerhans "in the name of His Majesty" , had them arrested and guarded in their offices. He gave the gendarmerie officials present in the town hall the order to cordon off the area and to ensure “peace and order”, although he even had a gendarme assigned to him “for better orientation”. He gave the chief of the local police station leave, whereupon he left his city hall office and went home to take a bath.

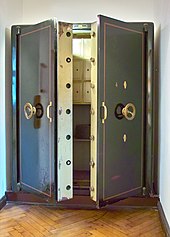

He instructed the treasurer of Wiltburg to close the accounts and told him that he would have to confiscate the holdings of the city treasury. After the money, which had to be withdrawn and fetched in parts from the local post office, had been counted, he had bags brought to him, into which he filled it with the help of the bearer who held the bags and then sealed them. The “seized” cash balance amounted to 3557.45 marks (adjusted for purchasing power in today's currency: around 22,000 euros), with 1.67 marks missing from the target balance in the cash book. Voigt signed a receipt requested by the renter with the last name of his last prison director (“von Malzahn”) and the addition “Hi1.GR” (captain in the 1st Guard Regiment).

Finally the wrong captain let the mayor and the cashiers of Wiltburg in rented cabs under military guard by a Gardefüsilier and a instructed him policeman of the city police to the Neue Wache in Berlin bring after he the prisoner before parole had taken off, not try to escape to company. According to press reports, he had previously succeeded in blocking the Köpenick post office for calls to Berlin for an hour. Only after the prisoners had been removed were some city councilors able to notify the district office by telegram.

After the end of his action, Captain von Köpenick gave his troops the order to keep the town hall occupied for another half an hour. He himself made his way back to the train station under the eyes of a curious crowd. In the station restaurant, according to newspaper reports, he had “a glass of light served, which he emptied in one go” and disappeared on the next train in the direction of Berlin. Shortly afterwards he procured civilian clothes from a men's outfitter and left most of his uniform on the Tempelhofer Feld , where it was found by passers-by. He was arrested at breakfast ten days later after a former cellmate, who knew about Voigt's plans, tipped the police in anticipation of the high reward. Sentenced to four years in prison by the District Court II in Berlin "for unauthorized wearing of a uniform, offenses against public order , deprivation of liberty , fraud and serious forgery of documents ", he was pardoned by Kaiser Wilhelm II and on August 16, 1908 prematurely removed from Tegel prison dismiss.

There are contradicting statements about the motive for the attack. While Voigt himself always claimed in court, in his autobiography and in his later appearances that he only wanted to keep the money and actually steal a foreign passport, his biographer Winfried Löschburg suspects that Voigt was actually two million marks (today: around 13 Million euros), of which he had heard that they were in the safe in the Köpenick town hall.

Passports were not issued in the town hall, but in the district office of the Teltow district in Berlin. In view of his careful research before the crime, he should have known this. The fact that Voigt did nothing during the occupation of the town hall that would point to a search for passports, while “his entire systematic behavior towards the cashiers” (according to the judgment of December 1, 1906) is clear evidence of a deliberately planned procedure wearing. In fact, he had already planned the way he would proceed during his last stay in prison and reported it to his cellmate Kallenberg, whereas his illegal residence status, which he said he intended to end with a forged passport, only arose shortly before the crime. Correspondingly, the (altogether “remarkably benevolent”) royal district court also considered Voigt's claim that he originally only wanted a passport form to be “completely untrustworthy”.

As a mitigating circumstance, however, the court accepted that “after having served his last sentence, he tried seriously and - as far as it was up to him - successfully to earn his living honestly, and was well on his way to becoming a useful member of the civil society To become society, but that this endeavor is thwarted through no fault of his own and he is pushed back on the path of crime. ”In this respect, the court also recognized that Voigt's act was largely due to his hopeless situation as a criminal, who according to the rules of the time Police supervision could not hope for a secure residence status.

Contemporary response

All of Germany laughed at the stroke of genius. The Kaiser immediately requested a telegraphic report on the affair . While reading it, he too is said to have laughed and said: “You can see what discipline means. No people on earth imitate us! ”However, this saying of the emperor is not guaranteed. On the other hand, the note in a correspondent's report in the Daily Mail is viewed as historically secure , according to which Wilhelm II described the Köpenick perpetrator in a comment on the dossier as a “brilliant fellow”.

The editor of the Vossische Zeitung called the perpetrator in the introduction to his report from the morning of October 17, 1906, with a wink, a "robber captain" and recognized the suitability of the event on the stage, which he compared with daring romantic stories of robbers:

"An unheard-of crook, which is strongly reminiscent of the Russian bank robberies and at the same time looks like a funny operetta story, got the city of Köpenick upset yesterday afternoon."

The great echo in the press and in the cultural media and a large number of funny postcards, photos and satirical poems made the episode known throughout Germany and abroad and led to the reputation of Captain von Köpenick as the " Eulenspiegel of the Wilhelmine military state", which continues to this day. as the Luxembourg historian Marc Jeck calls him (see literature ). Journalists from all over the world traveled to the trial against Voigt . During his detention, the authorities were inundated with questions, greetings, autograph requests and requests for pardons for the perpetrator from home and abroad. Voigt himself was offered large sums of money for exclusive marketing of his story during his time in Tegel prison. With his early release he finally became an object of the entertainment industry .

In addition to amusement and malicious glee , thoughtfulness was also noticeable in public immediately after the event. Could it really be that an officer with no legitimation other than his uniform was suspending civil authority? Many saw this incident as a symptom of the precarious role played by the military in the German Empire .

The Berliner Morgenpost stated the day after the attack:

"That a whole community with all its public functions, yes, that a division of soldiers itself was duped by a single person in such an overwhelmingly funny and yet completely successful way, that in our country of unlimited uniform reverence has done a military garb which an old, crooked-legged individual had hung up in a makeshift manner. "

The commentator for the left-liberal Berliner Volks-Zeitung summarized the political symbolic content of the Köpenick crook on the same day as follows:

“As unspeakably funny, as indescribably ridiculous as this story is, it has such an embarrassingly serious side. The Köpenick crook is the most brilliant victory that militaristic thought has ever come to a head. Yesterday's intermezzo teaches in no uncertain terms: Dress up in a uniform in Prussia Germany and you are all powerful. […] Indeed: The hero of Köpenick, he really captured the zeitgeist. It is at the height of the most intelligent appreciation of modern power factors. The man is a real politician of the very first order. [...] The victory of military cadaver obedience over common sense, over the state system, over the personality of the individual, that is what revealed itself in a grotesquely horrific way yesterday in the Köpenick comedy. "

The columnist Paul Block admonished his readership a little more conciliatory in the evening edition of the Berliner Tageblatt of October 17, 1906:

“We notice that our predilection for military pomp and style, which is in the blood of every Prussian, has received too much nourishment in recent years. Therefore we have to keep our respect silent from now on. "

The overly 'respectful' behavior of the soldiers was also criticized in the press: They had the instructions of an improperly uniformed “captain who was noticeably not wearing a helmet but a cap” (as the Vossische Zeitung reported in the above-mentioned message) In addition, the upper cockade was missing (as confirmed by witnesses) and not allowed to obey so easily, it was said in many places. Voigt later wrote in his autobiography :

“What is all the talk that is used to criticize my approach, even my uniform ?! [...] For example, I would not have worn a helmet! - The helmet was quietly on the table in my apartment. However, I did not consider it necessary, according to the facts, to wear a helmet on my head for 17 hours for an official act that I could and would do more comfortably in my cap. "

Government agencies reacted to the incident by instructing officers not to rely solely on the uniform, but to request "appropriate evidence" of supervisor status.

The incident caused quite a stir abroad as well and was largely interpreted as a comical manifestation of Prussian-German militarism and the dominant role of the German military in the state and society.

"For years the Kaiser has been instilling into his people reverence for the omnipotence of militarism, of which the holiest symbol is the German uniform."

"For years the emperor has instilled awe in his people for the omnipotence of militarism, the most sacred symbol of which is the German uniform."

"With his bold act, the false captain made the German spirit of submission ridiculous all over the world," writes the Berlin non-fiction author Wilhelm Ruprecht Frieling in this context. Nevertheless, nothing changed in these conditions in Germany until the November Revolution of 1918. The politically questionable special position of the military as an “internal power instrument to maintain the system” and the “abuse of the military as a domestic political instrument of war”, which Stig Förster describes as the essence of “conservative militarism”, were instead continued to be active by the emperor and the political forces gathered behind him promoted. Thus, the requested Conservative MPs Elard of Oldenburg Januschau in a much more sensational Reichstag speech on 29 January 1910 in reference to the number of years past incident in Koepenick:

"The King of Prussia and the German Kaiser must at any moment be able to say to a lieutenant: Take ten men and close the Reichstag!"

In this context, the Köpenick incident can be categorized as a comedic forerunner of the Zabern affair , which at the turn of the year 1913/1914 (a few months before the outbreak of the First World War ) once again led to fierce discussions throughout Germany and across all social classes of military authorities against the civil administration. The outbreak of war and the political takeover of power by the military in the state during the course of the war ultimately led to the upheavals of 1918 , which made it necessary to redefine the role of the military in Germany and make the situation in the empire seem a distant past. Against this background, interest in the story of Captain von Köpenick reawakened at the end of the 1920s.

After release from prison

The " Köpenickiade " made Voigt world famous. He was pardoned by the emperor and released on August 16, 1908, on the same day he immortalized his voice in the form of a gramophone recording , for which he received 200 marks . In this recording he said:

“The longing grew in me to walk among the outdoors as a suitor. I have now become free, but I wish [...] and please God may save me from becoming outlawed again. "

In the following days, his appearance in Rixdorf caused tumultuous crowds, which even made it necessary for the police to intervene. 17 people were arrested within two days for disturbing the peace and similar violations . Four days later, Voigt was presented in Berlin on the occasion of the unveiling of his wax figure in the wax museum Castans panopticon Unter den Linden in turn the public, autographed photos and held speeches, but this was immediately forbidden.

Later he traveled all over Germany (for example Bonn on November 26th 1908) and appeared in pubs and at fairs. In halls or circus tents he acted as Captain von Koepenick and sold autograph cards with pictures of him in uniform or in civilian clothes. Individual members of the "troop" that he had commanded at the time also took part in the performances or had themselves photographed with him. In 1909 his autobiography was published by a Leipzig publisher : How I became a captain of Koepenick. My picture of life / By Wilhelm Voigt, called Captain von Köpenick .

Since he was under police supervision as a reportable criminal, Voigt, who "mostly received noticeable sympathy from the lower strata of the population" (as a report by a Saarland mayor says), repeatedly suffered harassment and even arrests by the local authorities who disliked the mockery of the state and the military that was latently associated with his appearance. Therefore he was looking for a new home and preferred to perform in other European countries. Allegedly he even managed to enter the USA in March 1910 , where he is said to have celebrated great success with his tour (which is not historically certain; it is only certain that the American circus Barnum and Bailey financed a tour through several European cities ).

On May 1, 1910, he received a Luxembourg ID and moved to Luxembourg, where - after the frequency of his public appearances had decreased - he mainly worked as a waiter and shoemaker. Thanks to his popularity he achieved a certain prosperity and was one of the first owners of an automobile in the Grand Duchy, in which he occasionally went on excursions with his landlady and her children. In 1912 he bought the house on Neippergstrasse (Rue du Fort Neipperg) No. 5, where he lived until his death.

Voigt came into contact with the Prussian military once again during the First World War . In Luxembourg, which was occupied by German troops, he was briefly taken into custody and interrogated. The lieutenant involved in the process noted in his diary: "It remains a mystery to me how this poor man was once able to shake the whole of Prussia."

Death and burial in Luxembourg

Wilhelm Voigt did not appear in public in the last years of his life. He died on January 3, 1922 at the age of 72, severely affected by a lung disease and completely impoverished as a result of war and inflation, in Luxembourg ( Limpertsberg district ) and was buried in the local Liebfrauenfriedhof ( French : Cimetière Notre-Dame). It is located in the Allée des Résistants et des Déportés . The funeral procession allegedly met a group of French soldiers stationed in Luxembourg. When the squad leader asked who the dead man was, the mourners replied “Le Capitaine de Coepenick”. Thereupon the troop leader, assuming that a real captain ( French: Capitaine ) was being buried here, instructed his people to allow the funeral procession to pass with a military note of honor for the deceased officer.

The Sarrasani Circus bought Wilhelm Voigt's grave in 1961 for 15 years and donated a tombstone at the same time. This showed the biting caricature of the head of an obviously German soldier with a spiked hat , who opens his mouth to give orders , framed by the inscription "Der Hauptmann von Köpenick". The grave has been tended by the city since 1975 and, at the instigation of some members of the European Parliament , the tombstone was also renewed. It now shows a spiked hat and the inscription "HAUPTMANN VON KOEPENICK". Underneath it is written “Wilhelm Voigt 1850–1922” in smaller letters, whereby the year of birth is incorrectly stated here. In 1999, the City of Luxembourg rejected the request to transfer the remains to Berlin. The house in which he lived until his death no longer stands.

Memorial sites and illustrative material

A memorial was erected in front of the town hall in Köpenick in 1996. The figure was designed by Spartak Babajan and cast in bronze by the Seiler art foundry. A Berlin memorial plaque for Voigt was also attached to the town hall . Inside the building there is a permanent exhibition of the Heimatmuseum Köpenick with numerous exhibits about the "Captain von Köpenick". In the film archive in Berlin an original film document Wilhelm Voigt exists.

In Wismar , a plaque was attached to the house at Lübsche Strasse 11, where Wilhelm Voigt had lived and worked with the court shoemaker H. Hilbrecht. A figure at Madame Tussauds was also erected in his honor.

Literary echo

Theater, literature, film and music

Immediately after the crime, even before the impostor was caught, the episode was prepared for the Berlin theater audience in the form of satirical performances. Vorwärts reported on such a cabaret sketch on October 19, 1906: “The stage has already taken over history.” In the daily revue in the Metropol-Theater “a number of soldiers marched up yesterday who limited themselves to all orders of a captain's nod ”. In the Passage-Theater (in the Berliner Passage at the corner of Friedrichstrasse and Behrenstrasse ) a Schwank entitled Sherlock Holmes in Köpenick was rehearsed and in the German-American Theater (in the Köpenicker Strasse in Berlin-Kreuzberg ) an interlude with the title Der Hauptmann von Köpenick in the farce built into the Wild West .

A first play (Der Hauptmann von Köpenick. A comedy in four acts) , the performance of which cannot be proven, was written in Berlin in 1906 by the playwright Hans von Lavarenz . In Mainz , Trieste (November 1906) and Innsbruck (January 1907) the world premieres of three apparently comical and comical pieces are documented, all of which were entitled The Captain von Cöpenick . A similar play (Der Hauptmann von Köpenick) came to the theater in Leipzig in 1912.

In 1908 (after Voigt's dismissal) a Kiel vaudeville brought a funny program called Der Hauptmann von Köpenick onto the stage. Wilhelm Voigt himself wrote in a letter to his friend Kallenberg that he had “had a great desire and interest” to see the performance. Although he traveled to Kiel specifically for this purpose, the authorities forbade him to enter the auditorium because they feared a crowd.

The immense public interest is also illustrated by the fact that the first film versions of the Köpenickiade existed as early as 1906: Less than three months had passed, there were already three short films (shot by Heinrich Bolten-Baeckers , Carl Sonnemann and an unknown Schaub) who reenacted the Köpenick incident in a documentary manner and brought the sensational topic to cinemas all over Germany.

Also in 1906, the well-known crime writer Hans Hyan published an illustrated volume of poetry entitled The Captain von Köpenick, a gruesomely beautiful story of the limited understanding of subjects . Hyan also wrote the foreword for the memoirs that Wilhelm Voigt published after his release from prison in 1909.

The first longer feature film was produced by the screenwriter and director Siegfried Dessauer , who filmed the bizarre episode of the false captain in 1926 under the title Der Hauptmann von Köpenick with Hermann Picha in the title role. In contrast to what is often read in catalogs, this film, the majority of which were destroyed in copies in the Third Reich , is of course not based on Zuckmayer's well-known drama, which was made a few years later.

Also before Zuckmayer, the Rhenish local poet and editor Wilhelm Schäfer took up the topic and in 1930 published an only moderately successful novel about the life of the shoemaker Wilhelm Voigt with the title Der Hauptmann von Köpenick . Schäfer devotes only a few chapters to the Köpenickiade itself, while beforehand he broadly describes Voigt's sad vagabond existence and tries to give a plausible psychological justification for the revenge of the humiliated cobbler.

In the same year Carl Zuckmayer , who had been made aware of the material by his friend Fritz Kortner and who, according to his own testimony, had deliberately not read Schäfer's book, wrote a three-act tragic comedy entitled Der Hauptmann von Köpenick. A German fairy tale in three acts . The play was premiered on March 5, 1931 at the Deutsches Theater Berlin , directed by Heinz Hilpert, with Werner Krauss in the title role. In the same year, directed by Richard Oswald, the first film adaptation for the cinema followed, in which Max Adalbert , who has now also embodied the role on stage, took on the title role.

Albert Bassermann played the role in a remake of Oswald's film made in 1941 while in exile in the US for the first time in English . Helmut Käutner , later a scriptwriter and initiator of the Rühmann film , recorded a very successful radio play based on the drama in 1945 . Other film adaptations followed, all based on Zuckmayer's play, some with well-known actors such as Heinz Rühmann (1956) and Harald Juhnke (1997). An English editor of Zuckmayer's drama was formed in 1971 under the title The Captain of Koepenick (translator was the English playwright John Mortimer ) and was in the same year with the famous Shakespeare -interpreten Paul Scofield in the title role in London premiered.

Another dramatic implementation of the subject in the form of the comedy by Paul Braunshoff , also published in 1932 under the title Der Hauptmann von Köpenick , remained largely unknown.

The captain von Köpenick also appears as a minor character in Otto Emersleben's novel In den Schründen der Arktik (2003) , in which Karl May and Wilhelm Voigt meet and the idea of the Köpenickiade emanates from May. The scene is based on the fact that May himself (as a con man) repeatedly faked public officials in his youth.

For the first time on the 100th anniversary of the Köpenickiade in 2006 and since then every year in October, the Zuckmayer play is staged in the ballroom of the town hall in Köpenick by the "Stadttheater Cöpenick".

Also for the anniversary year 2006, under the title Das Schlitzohr von Köpenick - Schuster, Hauptmann, Vagabund, a new play about Wilhelm Voigt was created, which the authors Felix Huby and Hans Münch wrote for the people's actor Jürgen Hilbrecht , a captain actor who already has this role embodied for years at the historical crime scene in Berlin-Köpenick and brings the history of Voigt closer to tourists and those interested in history. Extensive historical research preceded the piece; a number of new discoveries and so far little or no known details and episodes from the "real" life of the main character flowed into his plot. In this respect, the piece is suitable to complement the image of Wilhelm Voigt in the public , which today is almost exclusively shaped by Zuckmayer's interpretation and the films based on it, and to link it more closely to historical events.

Also at the historical crime scene since May 2000 there has been a half-hour street theater in front of the Köpenick town hall every Wednesday and Saturday at 11 a.m. In this small Köpenickiade, originally initiated in 2000 by the Treptow-Köpenick Tourist Association and since 2005 by the Köpenicker HauptmannGarde e. V. , the coup of October 16, 1906 is re-enacted in a humorously modified Zuckmayer version of Captain von Köpenick.

Since 2019 there has been an escape room on Schlossplatz in Köpenick , in which the story of the Captain of Köpenick can be re-enacted.

Plot from Zuckmayer's drama

In the second and third act, Zuckmayer's piece deals with the time around the spectacular attack and in the first act a fictional history that takes place ten years earlier. In addition to minor changes (for example, Voigt's place of birth is relocated near the Wuhlheide so that Voigt speaks Berlin dialect ), the main difference between the piece and reality is probably the stylization of Voigt as a 'noble robber'. Zuckmayer, for example, adopts Voigt's (hardly credible) self-portrayal, according to which the motive for his attack was exclusively the acquisition of a passport, which he urgently needed in order to be able to start a normal life again. However, since the office in Köpenick did not have a passport department, the culprit - the city treasury almost untouched - in Zuckmayer's play at the end voluntarily surrenders to the police and has a passport promised for the time after his release from prison.

The fact that Voigt, unlike in reality, purchases the entire uniform from a dealer - a rather banal change in itself - gives the 'blue skirt' its own story. By introducing the previous owners one after the other, Zuckmayer took the opportunity to review the history of some of the minor characters (the mayor of Köpenick, for example) against the background of a critical, sometimes even caricature, description of the conditions in the imperial army and the militaristic society of the former Time to tell, with the omnipresence of the military being staged again and again.

Individual episodes deal with the effects of the officer's code of honor on the personal life and the social position of the reserve officer or address the unconditional piety of a 'down-to-earth' Berlin soldier and worker, personified in the form of Voigt's brother-in-law, a staid NCO Army and State. Everyday phenomena such as the stereotypical question when looking for a job "Where do you have anyone?" Voigt, who is very prominent here, can be performed to celebrate the anniversary of the Battle of Sedan .

Zuckmayer (who was an avowed opponent of the emerging National Socialism at the time the play was written and whose mother came from an assimilated Jewish family) also takes up anti-Semitic clichés, as they were already widespread in the imperial era, in a caricatural manner, for example in the figure of enterprising Jewish shopkeeper Krakauer or in the depiction of the Jewish uniform tailor Wormser and his son, to whom he ascribes certain degrees of expression of the "Jewish racial characteristics" in the stage directions and thus also addresses the failure of Jewish assimilation in the empire.

Film adaptations

The most important films at a glance:

- 1906: Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (Bolten-Baeckers, 1906) - silent film by Heinrich Bolten-Baeckers with Ernst Baumann as Wilhelm Voigt

- 1906: Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (Buderus, 1906) - silent film by Carl Buderus and Carl Sonnemann

- 1907: Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (Schaub, 1907) - silent film with the actors of the Berlin Luisen-Theater

- 1908: The robber captain von Köpenick and his pardon - silent film report about Voigt's release from prison, the performance was banned by the police

- 1926: Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (1926) - silent film, directed and written by Siegfried Dessauer , with Hermann Picha in the title role

- 1931: Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (1931) - based on Carl Zuckmayer , directed by Richard Oswald, book by Albrecht Joseph, with Max Adalbert in the title role

- 1941: I Was a Criminal - remake of his film in English , made by Oswald in American exile, with Albert Bassermann in the leading role

- 1956: Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (1956) - directed and written by Helmut Käutner , with Heinz Rühmann in the title role

- 1960: Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (1960) - TV film based on Carl Zuckmayer, directed by Rainer Wolffhardt, with Rudolf Platte in the title role

- 1997: Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (1997) - directed by Frank Beyer , with Harald Juhnke in the title role

- 2001: Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (2001) - stage adaptation ( Maxim-Gorki-Theater ) based on Carl Zuckmayer, directed by Katharina Thalbach , Andreas Missler-Morell (TV director), with Katharina Thalbach in the title role

- 2005: Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (2005) - stage adaptation ( Schauspielhaus Bochum ) based on Carl Zuckmayer, directed by Matthias Hartmann, with Otto Sander in the title role

- 2011: The Captain of Nakara - film by Kenyan director Bob Nyanja based on a script by Cajetan Boy and Martin Thau , which sets the plot in a fictional African military dictatorship

Radio plays

All of the radio plays listed here were based on the play by Carl Zuckmayer.

- 1945: NWDR - Director: Helmut Käutner , with Willy Maertens (Voigt) and Eduard Marks , Fita Benkhoff , Inge Meysel , Gustav Knuth , Erwin Linder , Ida Ehre , Erica Balqué

- 1947: SDR - Director: Alfred Vohrer , with Kurt Rackelmann (Voigt) and Axel Kreuzinger , Kurt Norgall , Willy Hochapfel , Harald Mannl , Friedrich Schoenfelder , Fritz Umgelter , Gerti Fricke

- 1951: SWF - Director: Karl Peter Biltz , with Ernst Sladeck (Voigt) and Heinz Schimmelpfennig , Kurt Lieck , Max Mairich , Alois Garg , Kurt Ebbinghaus

- 1954: BR - Director: Heinz-Günter Stamm , with Paul Bildt (Voigt) and Friedrich Domin , Erika Riemann , Ursula Kube , Werner Hinz , Charlotte Witthauer , Fritz Benscher , Ernst Fritz Fürbringer

- 1955: SFB - Director: Carlheinz Riepenhausen, with Helmut Heyne , Franz Weber, Eduard Wandrey , Erich Fiedler, Richard Süssenguth , Robert Klupp and others.

- 1962: Polydor International GmbH - Production: Pali Meller Marcovicz , with Rudolf Platte (Voigt) and Bruno Fritz , Reinhold Bernt , Ilse Fürstenberg , Eduard Wandrey , Edith Hancke , Erich Fiedler - The radio play does not include the entire play by Zuckmayer, but only the 1st and 6th scenes of the 1st act, the 9th, 12th and 14th scenes of the 2nd act, as well as the 19th and 21st scenes of the 3rd act.

- 1964: SFB - Director: Boleslaw Barlog , with Carl Raddatz (Voigt) and Christian Rode , Klaus Miedel , Herbert Grünbaum , Klaus Herm , Friedrich W. Bauschulte , Eva-Katharina Schultz

music

- In 1968 Drafi Deutscher published the song Der Hauptmann von Köpenick .

literature

- Walter Bahn: Wilhelm Voigt, the captain of Koepenick. In: ders .: my clients (= big city documents , volume 42). Hermann Seemann Nachhaben, Berlin undated [1908], pp. 67–115 ( digitized version of the Central and State Library Berlin , 2014).

- Annette Deeken : The captain of Koepenick. In: Heinz-B. Heller , Matthias Steinle (ed.): Film genres - comedy. Reclam, Stuttgart 2005, pp. 280-285.

- Wilhelm Ruprecht Frieling : The captain of Koepenick. The true story of Wilhelm Voigt. With the original judgment of the Berlin regional court. Internet book publisher, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-941286-69-6 .

- Wilhelm Große: Explanations to Carl Zuckmayer: The captain von Köpenick (= text analysis and interpretation. ) (Vol. 150). C. Bange Verlag, Hollfeld 2012, ISBN 978-3-8044-1956-8 .

- Wolfgang Heidelmeyer (ed.): The case of Köpenick. Files and contemporary documents on the history of a Prussian morality. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1968.

- Robert von Hippel : The "Captain von Köpenick" and the residence restrictions of punished people. In: Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung. Vol. 11 (1906), Vol. 11, pp. 1303/1304 (published online here ).

- Marc Jeck: On the highest orders. Not a German fairy tale. The true life. In: Die Zeit , No. 42, October 12, 2006, p. 104 ( online ).

- Paul Lindau : The captain of Köpenick . In: Paul Lindau: Excursions into the criminalistic. Munich 1909, pp. 241-272.

- Winfried Löschburg: Without gloss and glory - The story of the captain of Köpenick. Ullstein, 1998, ISBN 3-548-35768-7 .

- Philipp Müller: Looking for the culprit. The public dramatization of crimes in the Berlin quayside area (= campus: historical studies. 40). Frankfurt am Main 2005.

- Matthias Niedzwicki: The basic right to freedom of movement according to Art. 11 GG - At the same time a contribution to the 100th anniversary of the Köpenickiade of the Captain von Köpenick. In: Administrative sheets for Baden-Württemberg. Journal of Public Law and Public Administration. 10/2006, p. 384 ff.

- Henning Rosenau : The captain von Köpenick a suspect? - Study on a judgment of the Royal District Court II in Berlin and a play by Carl Zuckmayer. In: ZIS . 2010, p. 284 ff .; contains a copy of the judgment of December 1, 1906 in the appendix ( digital version (PDF; 199 kB)).

- Claus-Dieter Sprink (Red.): Subordinate - yes! But under wat under ?! From shoemaker Friedrich Wilhelm Voigt to “Captain von Köpenick”. Exhibition in the town hall of Köpenick, commemorative publication for the 90th anniversary of the Köpenickiade on October 16, 1996. Köpenick, 1996.

- Wilhelm Voigt: How I became captain von Köpenick: my life picture. Various publishers 1909, 1931, 1986, 2006. ISBN 3-935843-66-6 (text also published online here ).

- Carl Zuckmayer : The Captain von Köpenick: A German fairy tale in three acts. Fischer, ISBN 3-596-27002-2 .

- Simplicissimus , issue 33 (special number), vol. 11 (1906/1907) of November 12, 1906, pp. 513-532.

Web links

- From petty criminal to millionaire. Book review on W. Voigt's picture of life

- Overview of the Hauptmann von Köpenick films in the Internet Movie Database

- Captain actor Jürgen Hilbrecht (updated 2019)

- Works by Wilhelm Voigt in the Gutenberg-DE project

Individual references and comments

- ↑ The name of the city at that time was in the official spelling Cöpenick . This spelling was not officially changed in Köpenick until January 1, 1931 . In contemporary documents (including official documents such as the judgment of the Berlin Regional Court on the act of Wilhelm Voigt), books and press reports, however, the spelling with the initial K has already prevailed since the beginning of the 20th century . In this article, the name is reproduced as Köpenick in the following (except in quotations from sources that use the Cöpenick spelling ).

- ↑ The amount stated in the receipt of 4,000.70 marks (instead of 3,557.45 marks) is explained by the fact that the court ruling accidentally included the coupons from the Köpenick city bond for 443.25 marks that Voigt had not taken with him .

- ↑ The judgment is printed in the Zeitschrift für Internationale Strafrechtsdogmatik 2010, pp. 294–298, online here (PDF; 199 kB).

- ↑ Meint Rosenau (see literature ), p. 287

- ↑ Zuckmayer, who processes contemporary press reviews and news in his drama, lets his characters report on the Emperor's saying (according to the author's memory, “credibly rumored ”). It is strongly reminiscent of the sentence attributed to Bismarck : “Nobody imitates the Prussian lieutenant.” Zuckmayer uses this well-known Bismarckian bon mot (cf. Louis Reynaud: Histoire générale de l'influence française en Allemagne , 13th edition, Paris 1924. p . in 231) ironic "the: unfamiliar form and the uniform Schneider Worms in his mouth old Fritz , the categorical imperative , and our drill regulations ! that makes us not to" even Karl Liebknecht takes in his work militarism and anti-militarism with special emphasis on international Youth Movement (Leipzig, 1907) refers to this when he says: “As allegedly nobody - to speak to Bismarck - has copied the Prussian lieutenant, so nobody has in fact been able to completely copy the Prussian-German militarism who since not only a state within a state , but actually a state above the state has become [...]. ”(Quoted from Volker R. Berghahn [Ed.]: Militarism . K Öln, 1975. P. 91)

- ↑ With his reference to the "Russian bank robberies" the editor is evidently alluding to the spectacular bank robberies by revolutionary groups for the purpose of foreign exchange, which have been reported more frequently in pre-revolutionary Russia since the unrest of 1905 . The bloodiest of them, the attack on the Bank of Tbilisi , in which 40 people died and in which Joseph Stalin was involved, did not take place until the following year (July 1907).

- ↑ Heinz Pürer, Johannes Raabe, Presse in Deutschland , UTB, 2007, ISBN 9783838583341 , p. 66

- ↑ Conduct of railway employees towards superiors who are not personally known . In: Eisenbahn-Directions Bezirk Mainz (Ed.): Official Journal of the Royal Prussian and Grand Ducal Hessian Railway Directorate in Mainz. February 16, 1907, No. 8. Announcement No. 74, p. 77.

- ↑ 100 years "Hauptmann von Köpenick" (Part I) ( Memento of the original from February 18, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (October 9, 2006 at 11:37 a.m. by Wilhelm Ruprecht Frieling)

- ↑ See Stig Förster: Military and Citizenship Participation. General conscription in the German Empire 1871–1914. In: Roland G. Foerster (Ed.): The conscription. Origin, manifestations and politico-military effect. Munich, 1994. p. 58

- ↑ XII. Legislative period , 2nd session, vol. 259, p. 898 (D)

- ↑ 1508: Captain von Köpenick released from prison on br.de

- ↑ Eva Pfister: Against the uniform fetishism. In: Calendar sheet. March 5, 2011, accessed March 5, 2011 .

- ↑ Ebba Hagenberg-Miliu: When the 'captain' was in Bonn. His deception in Köpenick made him famous. The Bonners received him euphorically. In: General-Anzeiger (Bonn) , 7./8. August 2021, p. 26

- ↑ Neue Zeit of May 20, 1966, p. 6.

- ^ Liebfrauenfriedhof Luxemburg-Limpertsberg. Retrieved August 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Märkische Oderzeitung from 18./19. March 2006, p. 14.

- ↑ Cöpenick City Theater

- ↑ Simone Jacobius: Müggelheimer has created a historic escape room. September 2019, accessed September 21, 2019 .

- ↑ Film posters and basic data of the film from 1931 from the West German sound film archive ( Memento from December 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Film posters and basic data of the film from 1956 from the West German sound film archive ( Memento from December 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Captain von Koepenick |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Voigt, Friedrich Wilhelm (full name); Voigt, Wilhelm |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German-Luxembourgish shoemaker and impostor (Captain von Köpenick) |

| BIRTH DATE | February 13, 1849 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Tilsit |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 3, 1922 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Luxembourg |