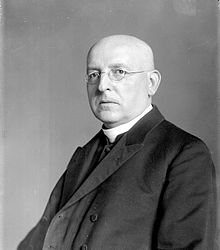

Ignaz Seipel

Ignaz Seipel (born July 19, 1876 in Vienna , † August 2, 1932 in Pernitz ) was an Austrian prelate , Catholic theologian and politician of the Christian Social Party . From 1921 to 1930 Seipel was their party chairman, dissolved the first coalition with the Social Democrats and served twice as Federal Chancellor (1922–1924 and 1926–1929). During Seipel's terms of office, on the one hand, the restructuring of state finances and the Federal Constitutional Amendment of 1929 fell ; on the other, he fought the Social Democratic Workers' Party and Austromarxism, especially in his second term, and supported the militarization of paramilitary militias such as the Home Guard .

Life

Academics and priests

The son of a Viennese fiaker graduated from the kk Staatsgymnasium in 1895 in the XII. Districts of Vienna in Meidling (today's BGRG Wien XII Rosasgasse), then he studied Catholic theology at the University of Vienna and was ordained a priest on July 23, 1899 . In 1903 he received his doctorate. theol. He was a member of KaV Norica Wien , then in the CV , now in the ÖCV . He later became an honorary member of the Catholic student associations “Deutschmeister Wien” as well as “Winfridia” and “Austria” (both Graz) in the KV / ÖKV . On May 11, 1930 he became an honorary member of the Catholic Austrian Student Union Asciburgia zu Oberschützen (today in the Middle Schools Cartel Association (MKV) founded in 1933 ).

In his book The Business Ethics Teachings of the Church Fathers , he was the first to use the term business ethics (Vienna 1907, page 304). In 1908 he completed his habilitation at the Catholic Theological Faculty of the University of Vienna . From 1909 to 1917 he was a professor of moral theology at the University of Salzburg . Here he also published his study Nation und Staat . In 1917 he was appointed to succeed the moral theologian Franz Martin Schindler as a university professor at the University of Vienna .

Politician

During the final disintegration of the monarchy was called on October 27, 1918 by Emperor I. Karl in the Ministry Lammasch , the last kk appointed government as Minister of Public Works and Social Welfare. At the beginning of November 1918 he had to hand over his German-Austrian official business to the Renner I state government appointed by the State Council on October 30, 1918 , where the public works were carried out by the Christian Socialist Johann Zerdik and the social agendas by the Social Democrat Ferdinand Hanusch ; the Lammasch Ministry, however, remained formally in office at the emperor's request until his own retirement.

While he was still imperial minister, Seipel was involved in the formulation of the waiver , which the emperor signed on November 11, 1918. On this day the emperor also dismissed the Lammasch Ministry.

On February 16, 1919, Seipel was elected to the Constituent National Assembly on the Christian social list of Vienna's Inner City (1st), Landstrasse (3rd) and Wieden (4th) districts. His parliamentary group elected him to the club presidency.

In this phase he prevented the split of the party in 1918 over the question of the abolition of the monarchy, which the Social Democrats and Greater Germans wanted. In March 1919 he spoke out against the affiliation euphoria of Social Democrats and Greater Germans, because the affiliation of German Austria to the German Empire was generally rejected by the Entente and would jeopardize the peace treaty. In 1920 he dissolved the CS from the coalition with the Social Democrats and concluded an alliance with the Greater German People's Party .

Seipel supported the new parliamentary democracy, but showed it a clear skepticism. Already in the preliminary deliberations on the Federal Constitution in 1920 and afterwards in 1922, Seipel spoke out in favor of a partial disempowerment of parliament in favor of a Federal President with significantly more extensive powers.

At the same time, Seipel supported the establishment of militant right-wing radical groups in Vienna, which was mainly reflected in the fact that Seipel had been a member of the secret organization " Vereinigung für Ord und Recht " ( Association for Order and Law ) since March 1920 , which included military figures as well as monarchist and Greater German representatives. This association planned the forcible elimination of social democracy and worked closely with Bavarian right-wing radicals around Georg Escherich .

From 1921 to 1930 Seipel acted as chairman of the Christian Social Party (CS). From May 31, 1922 to November 20, 1924, at the request of his party, Seipel was for the first time Federal Chancellor ( Federal Government Seipel I-III ) of a Christian-Social-Greater German coalition. In his first term of office, Seipel personally coordinated the distribution of industrial funds to right-wing militias. The main focus of Seipel was on the military efficiency of these militias, the ideological proximity to the CS party was secondary. This also explains why Seipel's main concern was the right wing fighters' association of German-Austria under the anti-Semite Hermann Hiltl , which he also armored with the financial means of the Hungarian Horthy regime .

Seipel rehabilitated the state finances with the help of a League of Nations loan ( Geneva Protocols ) and prepared the introduction of the shilling currency in 1925 , which was decided in December 1924 a few days after his resignation . However, this led to a sharp decline in the real income of the population and a sharp rise in the unemployment rate . After severe criticism from his own party and an assassination attempt on him on June 1, 1924, he resigned, but remained chairman of the Christian Social Members' Club . The assassin Karl Jaworek blamed Seipel for his personal poverty and shot the Chancellor, who had just arrived in Vienna by train, at close range on the platform of the Südbahnhof. For this Jaworek was later sentenced to five years in heavy prison.

In autumn 1924, the Bavarian foreign police, thought Adolf Hitler , who after his coup attempt in 1923 prison Landsberg since April 1924 imprisonment was serving from Bayern deported to Austria if he would prematurely released from prison. Seipel did not want the putschist and troublemaker back in Austria and informed Bavaria that Hitler had become a German through his service in the German army . Bavaria proved that Austria had recognized the Austrian citizenship of German soldiers in other cases; Seipel insisted on his right view.

Hitler stayed in Germany and resigned his Austrian citizenship in 1925, as he could no longer be deported from Germany as a stateless person. In 1932 he was formally naturalized in the German Reich .

Theodor Körner , an officer, a social democratic military politician in the First Republic, mayor of Vienna , then Federal President , paid tribute to Seipel during the 1924 election campaign. His biographer Kollman quoted from the Innsbrucker Volkszeitung that Körner described Seipel as "a character of integrity in every respect, a hardworking, selfless worker".

From 1926 to 1929 Seipel was again Chancellor, where he particularly fought against the Social Democrats. To this end, he joined the CS with the Greater German People's Party, the Landbund and the National Socialist Riehl and Schulz Group to form an anti-Marxist front ("Citizens' Block"). After the National Council election in Austria in 1927 , the basic stance against Austrian democracy was enforced. He also strengthened the role of the increasingly anti-democratic Home Guard and remained its most influential advocate until his death.

As a result, he became the great enemy of the Social Democrats, who after the police massacre of workers who demonstrated on July 15, 1927 on the occasion of the Schattendorfer judgment , referred to him as “prelates without mercy”, “prelates without mercy” and “blood prelates”. On July 26, 1927, Seipel had said in his statement on the events before the National Council: “Do not ask parliament or the government that appears lenient to the victims and the guilty of the unfortunate days, but would be cruel to the wounded republic. “Seipel's statement was followed by a highly controversial and heated parliamentary debate. The opposition picked out the abbreviated term without mildness and linked it with their criticism of the excessive police operation for which Police President Johann Schober was responsible.

In 1928, Seipel, in agreement with the governor of Lower Austria Karl Buresch, represented the interests of the Heimwehr by authorizing the deployment of the Heimwehr in Wiener Neustadt , as well as the temporally and spatially separate deployment of the Republican Protection Association , against the express request of Mayor Anton Ofenböck . As Federal Chancellor he was able to show his strength with a massive contingent of gendarmerie and military, there were no violent incidents on the day of the march.

Seipel resigned from the office of Federal Chancellor on April 4, 1929 and continued to run the business until May 4, 1929, when Ernst Streeruwitz succeeded him as head of government. (A total of five federal governments of the First Republic were under Seipel's leadership.)

He was not satisfied with the form of government of the First Republic; he was an essential operator of the strengthening of the role of the Federal President, as it was realized with the Federal Constitutional Amendment 1929 , which Seipel negotiated himself with the Social Democrats, and "probably thought of himself as the future holder of the office". In addition, under the political slogan of "true democracy", he propagated a cleansing of the system from the "evil of party rule":

“I myself do not attach too much importance to the mere reform of the electoral law and the electoral code; I see the root of the evil in the type of party rule that developed in the times of constitutional monarchy and that went unchecked after the monarchical correction fell away. In my opinion, the one who saves democracy is who cleanses it of party rule and thereby restores it. "

In 1930 Seipel was briefly foreign minister in Carl Vaugoin's cabinet . After the collapse of Creditanstalt in 1931, he was supposed to take over government business again, but was unsuccessful in forming a government.

Decades later, Bruno Kreisky , Social Democratic Chancellor 1970–1983, criticized his own party in this context. Seipel offered Otto Bauer , the leading head of the Social Democrats, a coalition at the height of the global economic crisis. The party executive did not respond. “… In retrospect, it seems to me clearly wrong not to advocate compromise more strongly in order to be in government at such a critical moment. ... In my opinion this was the last chance to save the Austrian democracy, "wrote Kreisky in 1986.

While Seipel's policy was initially shaped by the belief in Austria's independence, he later took the view that without the German Reich no Austrian policy would make sense.

Seipel suffered from diabetes mellitus , the consequences of the attack on him, and from tuberculosis . In December 1930 he therefore stayed in Meran for a cure , where he stayed in the “Stefani” diet sanatorium and was supported by Pius XI. was contacted by letter. He died in 1932 in the Wienerwald sanatorium in Lower Austria . Otto Bauer dedicated an obituary to him in the Arbeiter-Zeitung , in which he certified Seipel “honest inner conviction”:

“He fought us with all means and all weapons, and so did we. The fact that he was not a man of compromise, but a man who only felt comfortable in ruthless struggle, may often, especially in the years since 1927, have been a source of misfortune for the country; but whoever is a fighter himself will not deny the real fighting nature in the enemy camp with human respect. Now he's dead; the bourgeois parties have no personality above mediocrity. We can say of him on his bier: he was a man, take everything in everything. The soldier does not refuse the last military honors to the fallen enemy. So we send three volleys over the stretcher to the big enemy. "

Since Seipel was regarded by the Social Democrats as the refuge of reaction and the epitome of the alliance between clericalism and capitalism, the party base received the article with incomprehension. Bauer felt compelled to point out the difference between “emotional socialists and trained Marxists” in another article. While the emotional socialist hates the capitalist and the spokesmen of the capitalist world, the Marxist sees his opponents as creatures of a hostile social order. Seipel “is to us, precisely because we are Marxists, because he has fought us and we have fought him, not a villain, but the 'creature of relationships that he remains social, no matter how much he may subjectively rise above them '. "

Commemoration

In the Austro-Fascist corporate state , Seipel was the founding father of the regime: On the initiative of Hildegard Burjan , supported by Federal Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß , the Christ the King's Church , designed by Clemens Holzmeister , was built in the Viennese workers' district with the current name Rudolfsheim-Fünfhaus (15th district). (It is only six blocks from Seipel's birthplace.) Seipel's coffin was buried in the church's crypt in the fall of 1934. Dollfuss, governing dictatorially, had been murdered by a National Socialist two months earlier. Dollfuss' successor Kurt Schuschnigg had Dollfuss buried there too; the church was called "Seipel-Dollfuss Memorial Church" by the regime.

After the annexation of Austria , the Nazi regime had both coffins reburied in 1939: Seipel's coffin was buried in an honorary grave in Vienna's central cemetery (group 14 C, number 7). The burial ground is right next to the presidential crypt in front of the then "Dr. Karl Lueger Memorial Church", known as the cemetery church of St. Karl Borromeo ; Seipel's grave is located between the graves of the poet Anton Wildgans and the opera singer Selma Kurz . Dollfuss was buried in the Hietzingen cemetery .

On April 27, 1934, the dictatorial city administration named the then Ring of November 12 (commemoration of the founding of the republic), part of Vienna's Ringstrasse , in the section in front of the parliament, Dr.-Ignaz-Seipel-Ring. This was renamed in 1940 after the Nazi Gauleiter Josef Bürckel , on April 27, 1945 back to Seipel-Ring and on July 8, 1956 was given the current name of Dr.-Karl-Renner-Ring , after a different traffic area in the 1st district in 1949 was named after Seipel (see below).

A residential complex built in 1934/35 in the 3rd district of Vienna , Fasangasse 39-41, was named Ignaz-Seipel-Hof as part of the Assanierungsfonds .

The Dr.-Ignaz-Seipel-Platz in Vienna's 1st district was named after Ignaz Seipel in 1949 under the Social Democratic Mayor Theodor Körner , who was three years older than Seipel . The old town square is framed by the Academy of Sciences (Old University) and the Jesuit Church (University Church ); The square was previously named after both buildings.

In 1950, a Seipel bust created by Josef Engelhart in 1933 was placed in the arcade courtyard of the University of Vienna .

Artistic processing

In Hugo Bettauer's novel Die Stadt ohne Juden (1922) Ignaz Seipel is the person of the Christian-social Chancellor Dr. Karl Schwertfeger, who had all Jews expelled from the country, modeled on it. Seipel had seen in the Jews a "class" that represented mobile big business and a "certain kind of tradership" by which the people felt threatened in their economic existence. Austria, according to Seipel, is “in danger of being economically, culturally and politically ruled by the Jews.” As a solution to the so-called Jewish question, he proposed recognizing the Jews as a national minority. On the basis of this book, the film of the same name in 1924 was The City Without Jews from Hans Karl Breslauer . In 1977 Franz Novotny and Otto M. Zykan created the television production " State Operetta" for ORF, which portrays the civil war-like conflicts in Austria between 1927 and 1933 in a caricature-like manner. In the “State Operetta” Ignaz Seipel is portrayed as a “murderous clergyman”.

literature

- Klemens von Klemperer: Ignaz Seipel: Christian Statesman in a Time of Crisis . Princeton UP, Princeton, NJ 1972.

- German Ignaz Seipel. Statesman in a time of crisis . Styria, Graz 1976.

- Thomas Olechowski: Ignaz Seipel. Moral theologian, Imperial and Royal Minister, Federal Chancellor . In: Mitchell G. Ash, Josef Ehmer (ed.): University - Politics - Society . V&R Unipress, Göttingen 2015. pp. 271–278.

- Friedrich Rennhofer: Ignaz Seipel. Human u. Statesman. A biographical documentation . ( Böhlau Contemporary History Library , Volume 2), Böhlau, Vienna 1978, ISBN 978-3-205-08810-3 .

- Angelo Maria Vitale: The political one. Ignaz Seipel's thinking between scholasticism and corporatism. In: FS Festa, E. Fröschl, T. La Rocca, L. Parente, G. Zanasi (eds.): Austria in the thirties and its position in Europe. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-653-01670-3 .

- Entries in reference books

- DA Binder: Seipel Ignaz. In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 12, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2001–2005, ISBN 3-7001-3580-7 , p. 142 f. (Direct links on p. 142 , p. 143 ).

- Konrad Fuchs: Ignaz Seipel. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 9, Bautz, Herzberg 1995, ISBN 3-88309-058-1 , Sp. 1357-1358.

- Michael Gehler: Seipel, Ignaz Karl. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0 , p. 196 f. ( Digitized version ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Ignaz Seipel in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Ignaz Seipel in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Ignaz Seipel in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Ignaz Seipel on the website of the Austrian Parliament

- Entry on Ignaz Seipel in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- Funeral speech for Ignaz Seipel by Federal President Wilhelm Miklas (1932)

Individual evidence

- ^ Vlg. Wilhelm Braumüller, Vienna / Leipzig 1916

- ↑ Friedrich Funder : From yesterday to today. From the Empire to the Republic. 3. Edition. Herold Verlag, Vienna 1971, p. 468.

- ↑ Friedrich Funder: From yesterday to today. From the Empire to the Republic. 3. Edition. Herold Verlag, Vienna 1971, p. 471 f.

- ↑ a b c d Vienna's street names since 1860 as “Political Places of Remembrance” (PDF; 4.4 MB), p. 185ff, final research project report, Vienna, July 2013.

- ↑ Other spelling: Karl Jawurek; sz B. here

- ↑ Assassination attempt on Chancellor Seipel: "I think I was shot at". (No longer available online.) Die Presse , June 1, 2014, archived from the original on June 4, 2014 ; accessed on June 1, 2014 .

- ^ Historical Lexicon of Bavaria: Expulsion of Adolf Hitler from Bavaria

- ↑ Othmar Plöckinger: History of a Book: Adolf Hitler's "Mein Kampf". 1922-1945. Oldenbourg, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-486-57956-8 , p. 59.

- ↑ Eric C. Kollman: Theodor Körner. Military and politics. Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, Vienna 1973, ISBN 3-7028-0054-9 , p. 134.

- ↑ Stenographic Protocol. 7th session of the National Council of the Republic of Austria. III. Legislative period. July 26, 1927 (= p. 133 ff.)

- ↑ Seipel cabinet resigned . In: Vossische Zeitung , April 4, 1929, p. 1.

- ↑ Eric C. Kollman: Theodor Körner. Military and politics. Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, Vienna 1973, ISBN 3-7028-0054-9 , p. 344.

- ↑ Bruno Kreisky : In the stream of politics. The second part of the memoir. Siedler-Verlag, Berlin, Kremayr & Scheriau, Vienna 1988, ISBN 3-218-00472-1 , p. 354.

- ^ Religion.ORF.at: Opening of the Vatican archives important for Austria .

- ↑ Bruno Kreisky : Between the Times. Memories from five decades. Siedler-Verlag and Kremayr & Scheriau, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-88680-148-9 , p. 195 f.

- ↑ Alpenzeitung , edition of December 16, 1930, p. 5 ; Alpenzeitung , issue of December 24, 1930, p. 4 (with photo) .

- ↑ Thomas Olechowski: Ignaz Seipel - from kk minister to reporter on the republican federal constitution. In: Thomas Simon (ed.): State foundation and constitutional order. In development, Vienna 2011, p. 134. Online version, January 3, 2011: Kelsen Working Papers. Publications of the FWF project P 19287: “Biographical Researches on H. Kelsen in the Years 1881–1940” (PDF) (accessed November 23, 2017).

- ↑ a b quotation from Robert Kriechbaumer : Great stories of politics. Political culture and parties in Austria from the turn of the century to 1945. Böhlau, Vienna 2001, p. 190.

- ↑ Robert Kriechbaumer: Great stories of politics. Political culture and parties in Austria from the turn of the century to 1945. Böhlau, Wien 2001, p. 191.

- ↑ Helmut Weihsmann: Das Rote Wien: Social Democratic Architecture and Local Policy 1919–1934 . Promedia, Vienna 2001, p. 210.

- ↑ Frank D. Hirschbach: The novel "The city without Jews" - thoughts on March 12, 1988 . In: Donald G. Daviau (ed.): Austrian Writers and the Anschluss. Understanding the Past - Overcoming the Past . Ariadne Press, Riverside, CA 1991, pp. 56-69, cit. P. 61.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Seipel, Ignaz |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian Catholic theologian and politician (CS), member of the National Council |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 19, 1876 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 2, 1932 |

| Place of death | Pernitz |