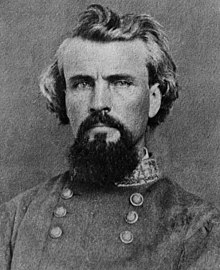

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest (born July 13, 1821 in Chapel Hill , Marshall County , Tennessee , † October 29, 1877 in Memphis , Tennessee) was an American plantation owner and general in the Confederate Army and probably the founder or at least one of the first leaders of the first Ku Klux Klans .

Life

Early years

Nathan Bedford Forrest came from a poor family. Before the Civil War he made it through the slave trade , including illegally smuggled Africans into the United States, and speculation with plantations , of which he owned several, to become a millionaire and one of the richest men in the South. He was also known in Memphis as a player and duelist and notorious for his often rough methods. When his uncle, with whom he did business, was killed in a shootout, he shot two of the opponents himself and wounded two others with the knife. He was elected alderman of the city of Memphis in 1858 .

Civil war

On June 14, 1861, he joined the army of the Confederate States as a volunteer and formally simple soldier ( private ) and quickly climbed the career ladder to equestrian general without formal military training. As a wealthy man, approached by the governor of Tennessee, he raised a mounted battalion at his own expense .

When the breakout of Confederate forces from besieged Fort Donelson was not approved, Forrest sought permission to break out with his battalion. He succeeded in leading most of his men and other soldiers, who mostly sat as second riders on the horses of the cavalrymen, through the siege lines. He led the rearguard while dodging Nashville . Mounted troops were of little use at the Battle of Shiloh ; his association therefore again brought up the rear during the evasive action. Forrest was wounded the day after the end of the battle.

After he was promoted to brigadier general shortly after the first battle for Corinth , he took the garrison and supplies from Murfreesboro with a newly formed brigade . In December 1862 and January 1863 he made some forays into western Tennessee, which led to the abandonment of General Ulysses S. Grant's attacks in Mississippi . A short time later he united his troops with those of General Joseph Wheeler . He made a fruitless attempt to take Fort Donelson. Forrest swore never to fight under General Wheeler again.

On June 14, 1863, Forrest was shot by a disgruntled subordinate, Andrew W. Gould , who Forrest himself fatally struck with his penknife . After his recovery he became division commander and soon afterwards commanding general of a corps at Chickamauga . After a series of discussions with Commander-in-Chief Braxton Bragg , Forrest was reassigned General Wheeler as a "punishment". His request for a mission in western Tennessee was then granted. The troop assigned to him was so small that he had to recruit. Soon he had enough people together to cause the Union generals a headache.

Immediately after Forrest's men had captured Fort Pillow on the Mississippi, there was a massacre there on April 12, 1864 , in which a large number of mainly black Union soldiers who had surrendered were brutally killed. The massacre resulted in US President Abraham Lincoln demanding that black soldiers be treated like other prisoners of war, even if they were former slaves. The south refused and the prisoner exchange came to a standstill.

In the months that followed, Forrest lost numerous soldiers at Brice's Crossroads, Tupelo, and other locations in Mississippi, but at Brice's Crossroads he inflicted a humiliating defeat for Northern forces with only half as many soldiers. But Forrest and his decimated troops could not stop the incursion of Union General James H. Wilson into Alabama and Georgia in the last months of the civil war. He was defeated and surrendered at the Battle of Selma on April 2, 1865 , and a few days later went into captivity with Richard Taylor .

post war period

Forrest had lost most of his slave and plantation fortune during the Civil War. He had freed his slaves before the end of the war. He became president of the Marion & Memphis Railroad in Selma , Alabama, but under his leadership it went bankrupt in the early 1870s, at a time of widespread financial crisis in the United States. Forrest was almost financially ruined and ran a prison farm on an island in the Mississippi.

He was of the first Federal Congress early 1867, the Ku Klux Klan in absentia to its first Grand Warlock ( Grand Wizard selected, and thus leader). The main aim of the clan was initially the repression and re-enslavement of blacks. The clan spread rapidly in the southern states. His acts of violence (including lynching and torture) were initially directed against black people and their protectors, as well as against the numerous former northerners who wanted to benefit from the reconstruction of the south after the civil war. Hundreds of black and white teachers and officials fell victim to him. Later the Klan turned against immigrant Jews and Catholic Irish, among other things. In 1869 the clan is said to have over 500,000 members. After the "Ku Klux Acts", a series of laws aimed at ending the acts of violence in the south, had been passed, Forrest dissolved it in 1871 and heralded the end of the first Klan. Some speak of Forrest's tactical maneuver to avoid persecution by the federal authorities; others claim that the ex-general no longer approved of this level of violence. A congressional committee found in 1871 that there was no evidence that Forrest led the clan, but that he had driven its dissolution.

Nathan Bedford Forrest died - presumably of complications from diabetes - on October 29, 1877 in Memphis, where he is also buried.

Forrest was known for his raids , with which he surprised the enemy and systematically destroyed the infrastructure in his hinterland. He used the cavalry mainly dismounted as infantry, which he could move quickly. His military motto was: “ Get there first with the most men. ”(German:“ Be the first with most men. ”).

aftermath

In the American southern states, especially in Tennessee, numerous monuments and parks commemorate him and schools are named after him. Forrest City , Arkansas is named after him. His role in the Fort Pillow massacre and in the Ku Klux Klan made him a controversial figure in the United States.

Nathan Bedford Forrest is also the namesake of the hero " Forrest Gump " in Winston Groom 's novel of the same name .

On February 10, 2011, the Fox News Channel reported that there were plans to feature Forrest on license plates. The Mississippi section of the NAACP petitioned Governor Haley Barbour to prevent this from happening.

In 2000, a monument to Forrest was unveiled in Selma, Alabama. In 2012 this monument was damaged by unknown persons.

In Rome , Georgia, a Nathan Bedford Forrest statue has stood in Myrtle Hill Cemetery in Chapel Hill since 1909 ; a high school is named after him in Tennessee, and also in Jacksonville , Florida . There, in 2008, the application to rename the Nathan Bedford Forrest High School was denied. The school got its name in 1959 after the civil rights movement had won a decisive victory in the US Supreme Court (keyword: Brown v. Board of Education ). In 2013 it was finally decided unanimously to rename the school and in 2014 it was renamed Westside High School . There is a bust of Forrest in the Tennessee House of Representatives .

literature

- United States War Department: The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies . Govt. Print. Off., Washington 1880-1901.

- Robert Underwood Johnson, Clarence Clough Buell: Battles and Leaders of the Civil War . New York 1887.

- James M. McPherson : Battle Cry of Freedom . Oxford University Press, New York 2003, ISBN 0-19-516895-X .

- Paul Ashdown, Edward Caudill, “What Can We Say of Such a Hero?” Nathan Bedford Forrest and the Press . In: David B. Sachsman, S. Kittreel Rushing, Roy Morris Jr. (Eds.): Words at War: The Civil War and American Journalism (The Civil War and the Popular Imagination). West Lafayette IN 2008, pp. 319-327.

- Interview with Nathan Bedford Forrest . In: Cincinnati Commercial , August 28, 1868 (i.e. 40th Congress, House of Representatives, Executive Documents No. 1, Report of the Secretary of War, Chapter X, p. 193)

Web links

- Nathan Bedford Forrest in the database of Find a Grave (English)

Notes and individual references

- ↑ Brigit Katz: New Historic Marker Highlights Nathan Bedford Forrest's Ties to the Slave Trade. Retrieved July 13, 2021 .

- ↑ tennessee-scv.org

- ↑ See James M. McPherson: Battle Cry of Freedom , p. 748. The fact that a massacre actually took place was denied by representatives of the southern states. But today it is considered certain by historians. See the article Battle for Fort Pillow for details .

- ↑ Arlin Turner: George W. Cable's Recollections of General Forrest . In: The Journal of Southern History , Vol. 21, No. 2, May 1955, p. 224 ff.

- ↑ In his dialect: to git thar fust with the most men. Bruce Catton: The Civil War , 1971, p. 160.

- ^ Nathan Bedford Forrest State Park. Retrieved July 13, 2021 .

- ^ Proposed Mississippi License Plate Would Honor Early KKK Leader . In: Fox News , February 10, 2011.

- ↑ KKK leader on specialty license plates? Plan in Mississippi raises hackles . In: Christian Science Monitor , February 11, 2011.

- ^ Group Wants KKK Founder Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest on License Plate . In: ABC News , February 10, 2011.

- ↑ Haley Barbour Won't Denounce Proposal Honoring Confederate General, Early KKK Leader . In: CBS News , February 16, 2011.

- ↑ Nathan Bedford Forrest Monument - Selma, Alabama. Retrieved July 13, 2021 .

- ↑ Bust of Civil War General Stirs Anger in Alabama . In: New York Times , August 24, 2012.

- ↑ Jennifer Lawinski: Florida High School Keeps KKK Founder's Name. March 25, 2015, Retrieved July 13, 2021 (American English).

- ↑ Scott Barker: Nathan Forrest: Still confounding, controversial . In: Knoxville News Sentinel , February 19, 2006.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Forrest, Nathan Bedford |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | General of the Army of the Confederate States of America |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 13, 1821 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Chapel Hill , Tennessee |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 29, 1877 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Memphis , Tennessee |