Battle of the Chickamauga

| date | September 18-20, 1863 |

|---|---|

| place | Catoosa Counties and Walker Counties , Georgia, USA |

| output | Confederation victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

|

56,965

|

66,000

|

| losses | |

|

16,170

1,657 killed 9,756 wounded 4,757 missing |

18,454

2,312 killed 14,674 wounded 1,468 missing |

Chattanooga II - Davis' Cross Roads - Chickamauga

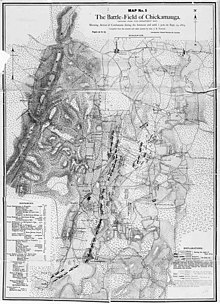

The Battle of Chickamauga took place from September 18-20, 1863 during the War of Civil War in northern Georgia . It was named after the Chickamauga brook , which flows into the Tennessee near Chattanooga , Tennessee . Because of the victory of the Confederates under General Bragg over the Generals of the Northern States Rosecrans and George Henry Thomas , the Northern Army was forced to evade to Chattanooga.

After the loss of Vicksburg and the lost Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the Confederation Army fought a victory over the Union in one of the most costly battles of the Civil War.

prehistory

While Ulysses S. Grant went on the offensive in Vicksburg , Mississippi and Joseph Hooker in Virginia , the Cumberland Army under William Starke Rosecrans remained inactive for a long time. In June, Rosecrans began the Tullahoma campaign . Although heavy rains delayed his advance and he lost the element of surprise, he maneuvered the Confederates so skillfully that their Commander-in-Chief Braxton Bragg decided to evade as far as Chattanooga.

Abraham Lincoln's plan was for Rosecrans to march on Chattanooga with the Cumberland Army, while the Ohio Army, under Ambrose E. Burnside, would advance against Knoxville. Rosecrans refused to march until August 16. It was only on a direct order from General Henry W. Halleck that he set off with the army. At the same time the Ohio Army marched with 24,000 men in four columns on Knoxville. The city's 10,000 defenders abandoned the city, and on September 3, Burnside's forces occupied Knoxville. The Confederates evacuated to Chattanooga, whose residents were evacuated from Bragg to Georgia on September 8. Bragg took up positions south of the city.

In order to take up the fight against Rosecrans, General Joseph E. Johnston strengthened Braggs troops by two divisions . President Jefferson Davis , who knew about the bad morale of the Tennessee Army , wanted to appoint Robert Edward Lee as its commander-in-chief, but who intended to continue to take action against Major General George Gordon Meade at Rappahannock . President Davis then dispatched Lieutenant General James Longstreet with two divisions to Georgia. Beginning on September 9th, the troops moved by rail. However, since Rosecrans held eastern Tennessee, they had to drive over 1,440 kilometers through South and North Carolina on ten different routes. Almost half of the troops arrived in time for the battle.

Now that Bragg knew reinforcements were on the way, he attacked. By apparently overflowing deserters, he let the rumor spread that the Tennessee Army was on the retreat. Bragg gave three orders to attack the Cumberland Army, which had several open flanks in the hilly terrain. But the respective officers refused to attack. Rosecrans finally assembled the three columns of his army in the valley of West Chickamauga Creek.

When Longstreet's vanguard arrived on September 18, they were first led by John Bell Hood , a Texan who had lost an arm in Gettysburg. Bragg could now bring superior forces into the field and probably would have managed to roll up Rosecrans' flank with his army, but the Confederate advance was halted by Union cavalry . During the night, a Union corps under George H. Thomas succeeded in a forced march to strengthen the left flank of the Union troops. When Union and Confederate patrols clashed on the afternoon of September 18, the greatest battle between Mississippi and Appalachians began.

The Cumberland Army, commanded by Rosecrans, consisted of about 57,000 men:

- XIV Corps (Major General George H. Thomas ) with the divisions of Major Generals James Scott Negley and Joseph J. Reynolds and those of Brigadier Generals Absalom Baird and John M. Brannan .

- XX. Corps (Major General Alexander Mc.D. McCook ) with the divisions of Brigadier Generals Jefferson C. Davis and Richard W. Johnson as well as Major General Philip Sheridan .

- XXI. Corps (Major General Thomas L. Crittenden ) with the divisions of Brigadier Generals Thomas J. Wood and Horatio P. Van Cleve as well as Major General John M. Palmer .

- Reserve Corps (Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger ) with Brigadier General James B. Steedman's division and Colonel Daniel McCook's brigade.

- Cavalry Corps (Brigadier General Robert B. Mitchell ) with the cavalry divisions of Brigadier General George Crook and Colonel Edward Moody McCook .

The Tennessee Confederate Army under Bragg Braxton numbered about 66,000 men:

- On the right wing the Corps Polk (Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk) with the divisions of Major General Benjamin F. Cheatham and John C. Breckinridge . Behind the cavalry corps under Brig. General Nathan Bedford Forrest with the divisions of Brig. Gen. Frank C. Armstrong and John Pegram .

- Hills Corps (Lieutenant General DH Hill ) with the divisions of Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne , Maj . Gen. Alexander P. Stewart, and General JB Kershaw

- Reserve Corps under Maj. Gen. William HT Walker with the divisions of Brigadier General States Rights Gist and St. John R. Liddell .

- On the left wing the Corps Lieutenant General James Longstreets, with the divisions of Major General John Bell Hood and Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws .

- Corps Buckner (Major General Simon B. Buckner ) with the divisions of Major General Thomas C. Hindman , Brig. Gen. William Preston and Bushrod R. Johnson . Behind the cavalry corps under Major General Joseph Wheeler with the divisions of Brig. Gen. John A. Wharton and William T. Martin .

The battle

September 18

For the advanced and mounted Union Brigade of Colonel John T. Wilder of the Reynolds Division, the battle began on September 18. Braxton Bragg, who still wanted to roll up the left flank of the Cumberland Army, sent his soldiers in division strength against George Thomas' corps. Hood's front division under General Bushrod Johnson crossed Chickamauga Creek over Reeds Bridge at 3:30 p.m., around the same time that Nathan Bedford was translating Forrest's cavalry at Fowler's Ford. They formed a group on the west side of the river halfway between the Reed and Alexander Bridges. Wilder's soldiers operated independently and were armed with the new Spencer bolt-action rifle that would soon prove to be one of the deadliest weapons of the Civil War. The brigades of Col. John T. Wilder and Robert Minty delayed the advance of the Confederates at the Reed and Alexanders Bridges. During the night Thomas moved his corps further north from the center and formed his corps on the streets to attack, which could also secure the retreat to Rossville Gap and Chattanooga.

September 19th

At dawn on September 19, Baird's division had arrived at XIV Corps as reinforcements, and General Thomas had set up his headquarters in Kelly House. He tried to protect Lafayette Road by having Brigadier General John Brannan's division advance east to defeat what he thought was a small and isolated force of the Confederate forces. Although covered by the forest on Chickamauga Creek, the move was risky, given that the Confederate Corps under Leonidas Polk was already concentrated less than a mile away. Both opposing forces were unaware of the close presence of the main enemy forces. Johnson's division of Longstreet's Corps (under Hood's command) was on the move all day with little water supply. After repeated attacks and counter-attacks, the Confederates captured Viniard Farm and controlled Layfayette Road.

Thomas received further reinforcements from Rosecrans, so that he only had to give up a little area, but with high losses for both sides. The XXI. Thomas L. Crittenden's Corps was concentrated at Lee and Gordon's Mills, where Bragg correctly suspected the Union's left flank. To the north of it was the XIV Corps, covering a broad front from Crawfish Springs (Negley division) via Glenns House (Reynolds division), Kelly Field (Baird division) to McDonald Farm (Brannan's division). The reserve corps operating on the sidelines under Major General Gordon Granger was spread across the northern end of the battlefield from Rossville to McAfee's Church. Separated by thick undergrowth, hills and forests, the Union's associations could neither communicate nor see each other. Overall, the confusion of the battlefield meant that the enemy troops often only sighted each other when they were only a few meters apart. This led to intense hand-to-hand combat with high losses on both sides. It also meant that the Union troops could not take advantage of the superior accuracy and range of their rifles. Just before dark, Cleburne's division entered the battlefield by crossing the Chickamauga at Thedfords Ford near Bragg's headquarters in Leets Tanyard. These troops reinforced the weak Confederate line to the north. In an unusual nightly attack, Cleburne's men advanced again on Winfrey Field. The Confederates could push back but not break through the Union's lines. In the evening General Longstreet had also arrived with two fresh brigades. Bragg ordered a staggered attack from right to left for the next morning.

September 20th

Bragg had formed his reinforced Tennessee Army into two parts for the attack, with General Polk in command on the right wing and James Longstreet on the left wing. Rosecrans, whose numerical and tactical situation had deteriorated considerably, convened a council of war. The presence of Deputy Secretary of War Charles A. Dana made it difficult to immediately consider the possibility of an orderly retreat. Rosecrans then decided against the withdrawal, strengthened his left wing and let the Union troops take up defensive positions.

The attack on Polk's wing was delayed by several hours. Slow communication hampered the early attack, which Hills Corps was supposed to launch at 5:00 a.m. When Polk received a message from General DH Hill at 5:30 a.m., he appealed to delay the attack. Bragg then delayed the initial move. When Hill ordered his men to finally attack at 9:30 a.m., the Confederates advanced on the Union parapets, some of which were strong, which Major General Thomas had built. The Breckinridge Division, relocated from the southern battle front, was able to break in briefly on the northern flank of XIV Corps and was then stopped by counterattacks. To the left the division of Cleburne attacked unsuccessfully, then the attack by Cheatham and finally that of the Walker division were repulsed, all advances shattered by Thomas's dogged defense.

Bragg broke off the attack in the north and then ordered General Longstreet to attack with all his troops on the left wing head-on. Longstreet struck around 11:30 am, under the command of Major General John Bell Hood , he had concentrated three divisions with eight brigades for a massive attack. In the lead, Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson's division advanced on Brotherton Road, followed by Hood's division, commanded by McLaws, during which two brigades were brought forward by Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw. To the left covered Major General Hindman's division, behind which William Preston's division acted as reserve. Rosecrans, meanwhile, led further reinforcements to his left wing by pulling divisions from Crittenden's corps to the north and his front with the troops of the XX. McCook's Corps replenished. During the regrouping, a staff officer overlooked a division of the Union that was on the right in the forest. Assuming there was a gap in the front, the division under General Thomas J. Wood was ordered there, which tore open an actual gap in the Union front elsewhere. Through this gap the troops attacked Longstreets and grabbed the Union troops on both flanks, whereupon they panicked around noon. The Union's resistance on the southern wing of the battlefield quickly dissolved. The rightmost divisions of Sheridan and Davis flooded back through McFarland's Gap, tearing parts of the Van Cleve and Negley divisions with them. When the right flank was rolled up by the Confederates, the generals of the Union forces - including Rosecrans, four division commanders and two commanding generals - fled to Chattanooga, 12 kilometers away.

Longstreet saw his chance and threw all his reserves forward for the decisive attack. The troops of the Union on the northern sector had not remained inactive and had built a new front, at right angles to the old one, on a mountain ridge. George Thomas had erected a final containment line along the ridge of Snodgrass Hill and further west to Horseshoe Ridge, which later earned him the nickname "Rock of Chickamauga". He received support from Gordon Granger, the commander of the Union reserve troops: without having received orders, Granger and his troops had marched in the direction from which he heard the noise of the battle. The repeatedly attacking troops Longstreets could be repelled. In the evening, Granger and Thomas' troops evaded orderly to Chattanooga. The next day, Longstreet and Nathan Bedford wanted to pursue Forrest of the Union in an attempt to destroy the Cumberland Army for good, but Braxton Bragg declined the request, given the army's losses. The Tennessee Army had suffered nearly 30 percent casualties in the dead, wounded and missing, including ten generals. John Bell Hood had a leg amputated. In addition, half of Bragg's artillery horses had been killed. Bragg therefore decided to starve Union forces in Chattanooga.

Aftermath

Braxton Bragg suspended three of his generals, including Leonidas Polk, for disobedience . On the Union side, Rosecrans was replaced by George Thomas, nerves at the end. An expeditionary force under Joseph Hooker marched towards Chattanooga, and Lincoln appointed Ulysses S. Grant as commander in chief of the western theater of war, which spanned the entire area between the Mississippi and the main Appalachian ridge . Grant loosened the siege of Chattanooga by a series of measures and it was possible to supply the trapped soldiers. In November, William T. Sherman arrived with 17,000 men. Longstreet was commissioned to liberate Knoxville. Grant began to finally liberate Chattanooga, which culminated in the Battle of Chattanooga .

literature

- Peter Cozzens: This Terrible Sound. The Battle of Chickamauga. University of Illinois Press, Urbana 1992, ISBN 0-252-01703-X .

- James A Kaser: At the Bivouac of Memory: History, Politics, and the Battle of Chickamauga. Peter Lang Publishing, New York 1996, ISBN 978-0-8204-2811-6 .

- Dave Powell: Decisions at Chickamauga: The Twenty-four Critical Decisions that defined the Battle. University of Tennessee Press, Chicago 2018, ISBN 978-1-62190-411-3 .

- Michael Solka: Chickamauga 1863. Publishing house for American studies, Wyk auf Föhr 1993, ISBN 3-924696-91-8 .

- Matt Spruill (Ed.): Guide to the Battle of Chickamauga. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence 1993, ISBN 978-0-7006-0596-5 .

- Steven E. Woodworth: Six Armies in Tennessee: The Chickamauga and Chattanooga Campaigns . University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 1998. ISBN 0-8032-9813-7 .

Web links

- Story about the Battle of Chickamauga

- http://npshistory.com/publications/civil_war_series/10/sec1.htm

Individual evidence

- ^ Union losses. Cornell University Library, January 12, 2017, accessed June 22, 2020 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXX, Part I, pp. 171–179).

- ↑ Fox's Regimental Losses, chap. 14 Confederate losses

- ^ Organization of the Cumberland Army. Cornell University Library, January 12, 2017, accessed June 25, 2020 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XXX, Part I, pp. 40-47).