Karl Kraus

Karl Kraus (born April 28, 1874 in Gitschin ( Jičín ), Bohemia , Austria-Hungary ; † June 12, 1936 in Vienna , Austria ) was one of the most important Austrian writers of the early 20th century. He was a publicist , satirist , poet , aphorist , playwright , promoter of young authors, language and culture critic and, above all, a sharp critic of the prevailing press and inflammatory journalism of his time or - as he himself put it - the journalle .

Life

Karl Kraus was the ninth child of the Jewish paper and ultramarine manufacturer and businessman Jacob Kraus (1833–1900) and his wife Ernestine (nee Kantor); the family belonged to the upper middle class. In 1877 the family moved to Vienna. Kraus' mother died in 1891.

After graduating from the Gymnasium Stubenbastei in 1892, Kraus began studying law at the University of Vienna . From November 1891 he sent the first of many articles to the monthly newspapers of the Breslau poet school under the editorship of Paul Barsch . He wrote articles for various German and Austrian magazines, especially literary and theater reviews . In April 1892, a review of Gerhart Hauptmann's drama Die Weber appeared as his first journalistic contribution in the Wiener Literaturzeitung. During this time Kraus tried his hand at acting in the suburban theater, which he gave up after the lack of success. A satirical magazine planned with Anton Lindner , for which contributions had already been made, for example by Frank Wedekind , was never published. Soon after, he changed the subject and studied philosophy and German until 1896 , but without completing his studies. His friendship with Peter Altenberg came from this time .

In 1897 Kraus succeeded with the publication of Die demolirte Litteratur a satirical settlement with the coffee house culture of Viennese modernism . The satire was Kraus' first major public success; Already at this point it was symptomatic that Kraus incurred the bitter hostility of the writers he had exposed. In the same year Kraus became the correspondent of the Breslauer Zeitung in Vienna .

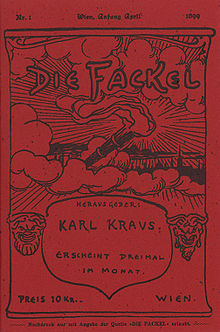

In 1898, Kraus, who had already helped found the magazine Die Wage , started considering publishing his own magazine. This magazine - Die Fackel - appeared for the first time in April 1899 with a length of 32 pages. In 1901 the first of many lawsuits took place, which were initiated by people who felt attacked by corruption allegations of the torch : here the theater critic and playwright Hermann Bahr and the artistic director Emmerich Bukovics . In the same year, after a three-month trip to Scandinavia, Kraus found that his publisher Moriz Frisch had taken possession of the torch by registering the title page of the magazine as a trademark under his own name and publishing a magazine called Neue Fackel . After fifteen trials, Kraus won the lawsuit. The torch seemed from then on self-published without title picture; Kraus also switched to the Jahoda & Siegel printing company.

In 1899 Kraus left the Jewish religious community. In 1911 he was baptized as a Roman Catholic on April 8th in the Karlskirche in Vienna . His godfather was Adolf Loos . In 1923 Kraus resigned from the Catholic Church.

In 1902 Kraus wrote his first contribution with the essay Morality and Criminality about what was to become one of the great topics of his work: the defense of sexual morality with judicial means, which was supposed to be necessary to protect morality (“The scandal begins when the police him puts an end to it. "). From 1906 on, Kraus published aphorisms in the Fackel , which were later summarized in the books Sprüche und contradictions (first edition 1909, further editions up to 1924), Pro domo et mundo (1919) and Nachts (1924). In 1910 Kraus held the first of his seven hundred public readings by 1936. In the same year the font Heine and the consequences appeared.

The first sensational “settlement” by Kraus took place in 1907 when he attacked his former patron Maximilian Harden on the occasion of his role in the Eulenburg trial.

On September 8, 1913, Kraus met the Bohemian Baroness Sidonie Nádherná von Borutín in Vienna , with whom he had a conflicted, intense relationship until his death. Kraus may have toyed with the idea of a marriage, but Rainer Maria Rilke thwarted it with the reference to "difference" (apparently what was meant was Kraus' Judaism ). On Castle Janowitz , the family of Nádhernys, created numerous works. Sidonie Nádherná became an important correspondent, “creative listener” and addressee of books and poems.

After an obituary for Franz Ferdinand , the heir to the throne murdered in the assassination attempt in Sarajevo , in the summer of 1914 the torch did not appear for many months and Kraus did not speak up again until December 1914 with the essay In this great time : “In this great time, that I still knew when she was so small; which will become small again if you still have time; […] In this noisy time, which is booming from the gruesome symphony of deeds that produce reports and reports of which deeds are to blame: in this time you may not expect a word of my own from me. ”In the following period, Kraus wrote against him War, several editions of the torch were confiscated, other editions were hindered by the censors.

In 1915 he began work on the play The Last Days of Mankind , parts of which were printed in advance in the Fackel and which appeared in 1919 in the form of special issues of the Fackel . The epilogue to this was published as a special issue as early as 1918 under the title The Last Night . Also in 1919 Kraus published his collected war essays under the title Last Judgment.

In 1921 Kraus published the satirical drama Literature or One will see there as a reply to an attack on him published by Franz Werfel under the title Spiegelmensch .

In January 1924 the dispute began with the extortionate publisher of the tabloid The Hour , Imre Békessy . This responded with character assassination campaigns against Kraus, who the following year under the slogan "Get out of Vienna with the villain!" Went to an "execution" and in 1926 managed to get Békessy to evade his arrest by fleeing Vienna. In 1927, Kraus asked Johann Schober , the Viennese police chief who was jointly responsible for the bloody suppression of the “ July Revolt ”, unsuccessfully on posters to resign. In the play The Insurmountable, which appeared in 1928, Kraus processed these two arguments. In the same year he published the files of the trial that Alfred Kerr had brought against Kraus, since Kraus had presented him with his earlier chauvinistic war poems in the torch .

From 1925, the Viennese doctor Victor Hammerschlag, together with the writer Sigismund von Radecki ("Homunculus") and others, campaigned heavily for Karl Kraus to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature . The driving force came from France , where Charles Andler nominated Kraus for the years 1926, 1928 and 1930, sometimes with colleagues.

From 1930 Kraus read on the radio, first in Berlin, then in Vienna, and made recordings for the record. In 1931 the State Opera Unter den Linden performed his adaptation of Offenbach's operetta La Périchole .

Kraus' new translation of Shakespeare's sonnets took place in 1932 . In 1933, after Adolf Hitler's " seizure of power " in the German Reich, no issue of the torch appeared for months . Kraus worked on a monumental text that was to have the takeover of power and the first months of National Socialist rule as its theme, but decided not to publish it. The work was only published posthumously in 1952 under the title The Third Walpurgis Night. In the October 1933 edition (the only edition of the torch that year), Kraus published the poem Man Don't Ask , which ends with the line: The word fell asleep when that world awoke.

In 1934, in an essay Why the Torch Does Not Appear, he justified the aforementioned waiver of publication of the Third Walpurgis Night, from which, however, he quoted long passages. With his support for the dictatorial ruling Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss , whom Kraus hoped would prevent the spread of National Socialism in Austria, Kraus alienated parts of his supporters.

In February 1936 Kraus was knocked down by a cyclist in the dark after issue No. 922 of the Torch had appeared. The consequences were increasing headaches and amnesia. On April 2, 1936, he gave his last lecture. After a severe heart attack in the “Café Imperial” on June 10th, Kraus died of a heart attack on June 12th 1936 in his apartment at Lothringerstrasse 6.

His grave, honored by the City of Vienna, is located in the Vienna Central Cemetery (Group 5A, Row 1, No. 33/34) near the old Israelite Department at the First Gate. Heinrich Fischer , Karl Jaray (1878–1947), Philipp Berger and Oskar Samek were appointed administrators of the estate by Kraus .

A memorial plaque is attached to the house at Lothringerstraße 6 in Vienna 4, where he had lived since 1912.

person

Karl Kraus polarized throughout his life. His appearance corresponded to this: His awareness of his own meaning was immense and conducive to this polarization. This self-image was not completely unfounded, because the listeners of his readings were fascinated by the personality of the presenter. His followers saw him as an infallible authority who gave all he sponsored every support to put them in the right light. Elias Canetti first heard of Kraus through acquaintances who described him as follows:

“This is the strictest and greatest man who lives in Vienna today. Nobody finds mercy before his eyes. In his lectures he attacks everything that is bad and corrupt. [...] Every word, every syllable in the torch is from himself. It is like being in court. He himself accuses and he judges himself. There was no defense attorney, that was superfluous, he was so just that no one would be charged who did not deserve it. He's never wrong, can't be wrong at all. [...] If he reads from it [from the last days of mankind ], one would be stunned. Nothing stirs in the hall, one hardly dares to breathe. […] Anyone who heard him never wanted to go to the theater again, the theater was boring compared to him, he was a whole theater by himself, but better, and this wonder of the world, this monster, this genius had the very common name of Karl Kraus . "

The Austrian writer Stefan Zweig described Kraus in his memoir Die Welt von Gestern (The World of Yesterday) as the “master of poisonous ridicule”.

For his numerous opponents, whom he created through the absolute and passion of his partisanship, however, he was a bitter misanthropist and a “poor wannabe” ( Alfred Kerr ) who indulged in hateful convictions and errands.

“Behind Karl Kraus there is no religion, no system, no party, Karl Kraus is always behind Karl Kraus. It is a self-contained system, it is a one-man church, it is itself God and Pope and evangelist and community of this confession. He speaks in his own name, on his own behalf and regardless of the response. He hates the audience of his reading evenings and hates the readers of his magazine, he forbids any consent ... and this is where the first irresolvable contradiction begins; because at the same time he depends on the applause of the audience, for which he comes to thank and which he proudly registers, at the same time he prints detailed approving reports in the newspapers ... If you want to ask about your mental disposition, you will find the obvious surface categories' vanity 'or' Megalomania 'can't do much ... I believe that two realizations most likely open the way to understanding the uniqueness of the phenomenon Karl Kraus and that they, related to each other, explain his development and his specialty ... Karl Kraus ... has as a young man of twenty-five years realizes what every intelligent, independent dissatisfied person dreams of at any time: he has created a forum for himself to express his opinion, to criticize, to accuse, to fight without hesitation and inhibitions, beyond all cliques and ties in absolute freedom ... twenty-fifth year until his death did only what he wanted. And, secondly, he was unable to do one thing that he wanted, and which, I believe, would have been his complete and final fulfillment, and was therefore condemned to circle it around his life in a roundabout way and only indirectly, temporarily to realize. At heart he was an actor, better a theater person; and he couldn't go to the theater. So ... for him, what might have been just a sideline, the main thing and, wherever conceivable, the theater had to be brought closer: 'When I lecture, it is not fictional literature. But what I write is printed acting. ' And: 'I am perhaps the first case of a writer who also experiences his writing as an actor.' "

Thomas Mann on Karl Kraus' reading evening on March 29, 1913 in Munich:

“His spiritual way of reading Jean Paul immediately captivated me very much. And the ingenious passion with which he, in his own so sharply and purely stylized writings, defends the great basic things of life, war, sex, language, art, against desecration and pollution, against the world of the newspaper, against civilization, It too has something spiritual, something religious, and whoever has at some point grasped the contrast between spirit and art, civilization and culture, will often feel sympathetically carried away by the satirical pathos of this anti-journalist. "

Ernst Krenek about Karl Kraus:

“It never came from the opinion to the word, but directly from the origin, from the thought. Therefore his opinions could seem to contradict one another. And from this he had the authority to judge those who only use the language to express the opinions they draw from the contradicting situations of this world. "

Karl Kraus and the language

Karl Kraus was convinced that the great evils of the world and of the epoch are revealed in every smallest discrepancy, which apparently has at most a local and temporal significance. So he could see in a missing comma a symptom of the state of the world that made a world war possible. One of the main concerns of his writings was to draw attention to the great evils through such small grievances.

For him the most important indicator of the grievances in the world was language. In the negligent use of language by his contemporaries, he saw a sign of the negligent use of the world in general. So could Ernst Křenek report the following typical for him remark about Karl Kraus: "When you look excited just about the bombardment of Shanghai by the Japanese and I Karl Kraus at one of the famous comma problems encountered, he said roughly: I know that all of which is pointless when the house is on fire. But as long as that is at all possible, I have to do it, because if the people who are obliged to always have made sure that the commas are in the right place, Shanghai would not burn. "

He accused the people of his time - not least journalists and writers - of using language as a means that one believes to be “mastered” instead of seeing it as an end and “serving” it. For Kraus, language is not a means of disseminating ready-made opinions, but rather the medium of thought itself and, as such, in need of critical reflection. It was therefore a major concern of Karl Kraus to “de-journalize” his readers and to “understand” in a “through and through journalized time that the spirit serves for information and has deaf ears for the harmony of content and form” to educate the matter of the German language, to the height at which one understands the written word as the naturally necessary embodiment of the thought and not just as the socially obligatory shell of the opinion ”.

How far the language of his contemporaries had deviated from the thought and the imagination of what was spoken becomes clear in the meaningless phrases, the metaphors of which came from times long past - when, for example, in April 1914 the Torch was quoted: “'The author is decided a thorough expert on international naval conditions and has broken many a lance in various brochures for the strengthening of the sea power of our fatherland. ' Although such are no longer even used on land. "

Language does not allow itself to be put entirely at the service of human intent, but rather shows the true conditions in the world even in its most mutilated form. For example, the war profiteers unconsciously referred to the cruel slaughter during the war when they described the war as "murderous hate" (Austrian: great fun).

This fixation on the “correct language” was seen by many contemporaries as at least quirky and superficial. By identifying the main enemy in the press and the “literary underworld”, other social and cultural fields remained fuzzy with him, which is also reflected in his fluctuating political stance (at times he sympathized with social democracy, at times with Archduke Franz Ferdinand ). Albert Fuchs - originally an admirer of Kraus - summed it up as follows: “She [Karl Kraus' philosophy] demanded that I speak decent German. Otherwise she didn't ask for anything. "

Karl Kraus mastered word games with and about names. He glossed the imprisonment of the fraudulent banker Reitze as follows: "The Stein penal institution does not lack a certain Reitze". In his earlier years he courted the young actress Elfriede Schopf, who, however, was in the firm hands of the Burgtheater hero Adolf von Sonnenthal . The news of his sudden death elicited the exclamation: "Now you should grab the opportunity!". He commented on the sometimes not easy to understand statements of communist parties as "gibberish".

Karl Kraus and the press

Karl Kraus' campaign against the press ("Journaille", "Inkstring", "Catchdogs of Public Opinion", "Preßmaffia", "Pressköter") ran through his entire life's work. He accuses her that “only what is between the lines is not paid for”. In particular, he turns against the Neue Freie Presse (today: Die Presse ), of which he says that “there is no wickedness that the editor of the Neue Freie Presse cannot represent for real money, and that there is no value that he expounds Idealism is not ready to be denied ”. The phenomenon is not new (and extends to other controllers of public affairs and opinions) that everything is subject to criticism from the press - with the exception of the press itself.

Kraus was able to justify his allegations with facts. So he proved the payment of so-called "lump sums" to newspapers with which large commercial enterprises bought the good behavior of the newspapers. He was able to prove a connection between attacks by a newspaper on a company and their expiry after a few advertisements were placed by the same.

Karl Kraus liked to expose the press, especially in his earlier years, by launching one or the other so-called pit dog with a lot of impressive-sounding but meaningless technical terms.

- In the beginning there was the press

- and then the world appeared.

- In your own interest

- she has joined us.

- After our preparation

- God sees that it succeeds

- and so the world to the newspaper

- he brings [...]

- You read what appeared

- they think what you mean.

- Even more can be earned

- when something does not appear. [...]

The fight against the press is inseparable from the fight against the phrase: "... it is my deepest conviction that the phrase and the thing are one". Anyone who writes impure also thinks impure: “People still believe that the human content can be excellent if the style is bad and that the attitude is established quite separately. But I maintain ... that nothing is more necessary than trashing such people as waste. Or a state parliament would have to be constituted on language, which, as for every adder, offers a reward for every phrase hunted down. "

He is also accused of having driven his hatred of the liberal press, at least in the pre-war years, to anti-liberalism with an ultra-conservative tinge; many positions from this period cannot be taken literally.

Karl Kraus and Judaism

In 1899 Karl Kraus left the Jewish cult community and was baptized as a Catholic in 1911 after a few years of non-denominational status. This step remained unknown to the public until Kraus resigned from the church in a sensational way in 1922 - as a protest against a church which the Salzburg Collegiate Church "gave" to Max Reinhardt staging theater performances in it.

Kraus' writings pick up on some anti-Semitic expressions: For example, he called “Jewish-German” as “mauscheln” and the work of the editor of the Neue Freie Presse , Moriz Benedikt , as “ritual robbery” (see legend of ritual murder ). Even in Kraus' long-running polemical argument with Heinrich Heine , a German-Jewish writer like Kraus himself, whom he accuses of having loosened the bodice of the German language, so that every clerk can now finger their breasts, there are numerous hidden and hidden ones open allusions to Heine's Judaism (while Heine was baptized in June 1825).

This ambivalence towards one's own origin and the tendency to view the supposed “typically Jewish” characteristics as primarily negative was not unusual in his time. A Jewish community in Vienna willing to assimilate and largely already assimilated encountered the Eastern Jewish co-religionists streaming from Galicia to Vienna with their caftan , sidelocks and tefillin , which were felt to be out of date - and felt strangeness and anxiety. The “ West Jews ” made it a point not to be confused with the “ East Jews ”, they were particularly fond of Germany and Austria and sometimes presented themselves more German than the Christian Germans, were culturally extremely committed, economically successful and, in the face of a time, wanted something the atavistic hostility towards Jews had apparently overcome once and for all , leaving behind the smell and humiliation of the centuries-old ghetto without being reminded of it again by Eastern European fellow believers. In addition, there was concern that the “Eastern Jews” might revive old resentments through their appearance and their foreign customs - especially since the phenomenon of anti-Semitism was becoming more prevalent in Vienna and elsewhere towards the end of the 19th century. It took Martin Buber to rediscover the culture of Eastern Jewry .

Kraus, descendant of a wealthy family of upper-class industrialists, shared this feeling with the long-established Jews. The attitude of established Judaism to the Jewish question represented by Kraus can be seen well in his pamphlet A Crown for Zion (1898), which replied to Theodor Herzl's publication Der Judenstaat . The crown, actually the Austro-Hungarian currency (although a crown had to be deposited as a minimum donation in order to be eligible for participation in the Second Zionist Congress), was interpreted by Kraus as the crown of a would-be “King of Zion”. Kraus accused Zionism of making a historical mistake: it was leaving the only promising path of assimilation and leading astray, and it was also playing into the hands of those who wanted to separate Jews from non-Jews. The militant Zionists in particular had succeeded in “convincing Christians, who so far had no taste for anti-Semitism, of the salutary nature of the idea of isolation”. Zionism will have to capitulate before integration: “It is hardly to be assumed that the Jews will move into the promised land this time dry-footed, another red sea, social democracy, will block their way there.” In addition, Kraus also felt confronted Because of his Jewish descent, he was basically not obliged to allow himself to be absorbed by the Zionist idea and to opt for a Jewish state of his own: he felt himself to be Austrian and Viennese. In this, Kraus knew that he was in agreement with a significant part of the old-established Jewry, which - no matter how much they might see the need for a solution for the oppressed Eastern Jewry - did not recognize a meaning and purpose of the Zionism movement for itself because they did not see or wanted to see what Theodor Herzl had deduced in the midst of the tumult in the course of the Dreyfus Trial .

The distance to their own roots has been discharged in quite a few members of the assimilated Jewry in an attitude that has been described as " Jewish self-hatred ". Although there was also no lack of voices who viewed hasty assimilation as undignified, the tenor was to regard the term “Jewish characteristics” as having negative connotations and to ignore one's own Jewish origins as far as possible - for which the work of Karl Kraus, but the former Has not denied, exemplifies in many ways.

But Kraus was far more likely than the Jews to find the anti-Semites among his contemporaries ridiculous. In the essay Er ist noch e Jud (October 1913) Kraus printed a letter from a reader, who asks him to explain whether he, Kraus, “adheres to nothing of all the qualities of the Jew” and “what position” Kraus to the sentence "which Lanz-Liebenfels also agrees with", namely that "one cannot withdraw from the race". Kraus explains that it is not his business to "let strangers break my head [...] My lack of education means that I can hardly say as much about the racial problem as is necessary to get in a halfway decent bowling club that considers itself to be considered an intelligent person. Even so, it was possible that a specialist like Dr. Lanz von Liebenfels, to whom my examiner also refers, addressed me as the 'savior of Ario-Germanism'. I do not know how this is done, since these racial anti-Semites also put forward the sentence: 'One cannot quit the race' […] I do not know whether it is a Jewish quality to find the Book of Job worth reading, or whether it is anti-Semitism to throw a book by Schnitzler in the corner […] I don't know about the race ”.

More than a quarter of a century after the publication of A Crown for Zion , Kraus wrote: "Since I was not born with as much conviction as a Zionist editor, I cannot possibly maintain what I wrote when I was twenty-three as a fifty-year-old." Regret as the idea that I could have omitted it at the time or did it differently can never take hold of me. That would only be possible if I knew that I would have done it against my convictions! "

Kraus seems to have been aware of the ambivalence of his traditional attitude to the Jewish question when, for example, on the Third Walpurgis Night, he printed a letter to the Westdeutscher Rundfunk , which in April 1933 had asked him to provide some sample copies of its translation of Shakespeare's sonnets. Kraus pretended to protect the editor "from a mistake that could bring you into contradiction with the guidelines for cultural criticism that apply in Germany": he himself is a Jewish author, but there is no reference to a "translation from the Hebrew ”(in the sense of a kind of literary Jewish star ). Karl Kraus was aware that the National Socialist racial ideology classified him as a Jewish author anyway.

plant

"The torch"

On April 1, 1899, Karl Kraus founded the magazine Die Fackel. In the preface to this he renounced all consideration of party political or other ties. Under the motto What we kill, which he countered the lurid What we bring in the newspapers, he told the world, especially writers and journalists, to fight against the phrase and developed into one of the most important champions against the neglect of the German language.

The development of the magazine Die Fackel is a biography of its editor. From the beginning, Karl Kraus was not only the editor, but also the author of most of the articles (sole author from 1912). While the torch was comparable to other magazines (such as Weltbühne ) at the beginning , it later became more and more the privileged form of his own literary expression. Karl Kraus was financially independent and didn't have to be considerate. So the torch was his work alone; only what he thought was right was printed in it. The last number, published four months before his death, ends with the word idiot.

Kraus' self-confidence was immense, his misanthropy legendary. A note published in Fackel in January 1921 could be described as a manifesto of his work:

“I // do not read any manuscripts or printed matter, // do not need newspaper clippings, // am not interested in magazines, // do not request any review copies and do not send any, // do not review books, but throw them away, // do not test talents , // do not give autographs [...] // do not attend any lectures other than your own [...] // give no advice and do not know anyone, // do not visit or receive anyone, // do not write a letter and do not want to read any and // refer to the utter futility of any attempt to determine any of the connections to any of the connections indicated here or, as always, interfering with my work in your imagination, increasing my discomfort with the outside world, and I only have the request to open all such undertakings, wasted postage and other costs, from now on to the Society of Friends Vienna I, Singerstraße 16. "

"The last days of mankind"

The last days of mankind is a "tragedy in 5 acts with prelude and epilogue". It was created in the years 1915–1922 as a reaction to the First World War .

"The Third Walpurgis Night"

The seizure of power in neighboring Germany seemed to leave Kraus speechless. It was not until October 1933 that he spoke up again with the thinnest torch (four pages) that he had ever published. In addition to a funeral oration for Adolf Loos , it only contains the following poem:

- You don't ask what I was doing all this time.

- I remain mute;

- and don't say why.

- And there is silence as the earth crashed.

- Not a word that met;

- one speaks only from sleep.

- And dreams of a sun that laughed.

- It passes;

- afterwards it didn't matter.

- The word fell asleep when that world awoke.

This statement in Torch No. 888 was commented on by Bertolt Brecht in a poem:

- When the eloquent apologized

- That his voice should fail

- The silence came before the judges' table

- Took the handkerchief from his face and

- Identified himself as a witness.

The National Socialist rulers immediately put Kraus' life's work on the “ list of harmful and undesirable literature ”. When the books were burned, however, his works were spared. Kraus was not pleased: “[...] this black list, the sight of which grips you with yellow envy. Where is justice then, if one has worked all one's life in a corrosive way, weakened the will to defend himself, advised against joining and recommended the country only to protect against the other, in the often (rarely with source) quoted knowledge that there was electrical lighting Barbarians live and that the people are judges and executioners. "

Kraus had by no means been idle in the months from the seizure of power in Berlin up to October 1933. He recognized the inhumanity and the danger of National Socialism early on . His thoughts on this can be found in the book Third Walpurgis Night, which begins with the famous words: “I can't think of anything about Hitler”. In this work, which was written in 1933 - in the first months after the National Socialist seizure of power - but was only published posthumously in 1952, there is the prophetic sentence that National Socialism was a nightmare from which - "after coping with the other slogan" - Germany " awaken ”. With the "other slogan" Kraus alludes to the second part of the Nazi slogan "Germany awake, Judah verrecke!"

The title refers The Third Walpurgisnacht therefore that Kraus's work alongside the two other famous literary Walpurgis nights in Goethe's Faust I and Faust II provides and with this, commenting on the hideous, grotesque ghosts of the Nazi nightmare by about Joseph Goebbels describes:

- How they please the satyrs;

- A goat's foot can dare anything there.

The writing is characterized by a logical conclusion from the beginnings of National Socialism to its progress and its end, based on the bestial deeds on the one hand, which the book cites in large numbers, and the language of the National Socialists on the other. He interpreted the peace oaths of the new rulers correctly: "We live [...] in an eternal circle and the world does not know its way around, although it is easier to recognize what is defensive than what is true, especially in the speeches of purely pacifist content behind which it is Thoughts presumed: si vis bellum, para pacem. "

Kraus worked on the Third Walpurgis Night from May to September 1933; it should appear as the output of the torch . It had already been set and the proofs had been checked when Kraus decided not to publish it. It was less the personal danger than the fear that the National Socialists could take revenge on innocent victims for a provocation for which, in all experience, they would blame larger circles than him alone. He himself confessed that he “regards the most painful renunciation of the literary effect less than the tragic victim of the poorest anonymously lost human life”. So it happened that The Third Walpurgis Night could only appear after the Second World War.

more publishments

Many of the larger essays Kraus also published as brochures, for example: The Hervay Case. 1904; Madhouse Austria. 1904; The child friends. 1905; The Riehl trial. 1906. Since Karl Kraus wrote with the knowledge that his work would outlast his time, he published many of his articles collected and revised in book form. The early book publications include: Morality and Criminality 1908, The Chinese Wall 1910, Last Judgment 2 volumes 1919.

Kraus has dealt intensively with the work of Shakespeare . Subsequent to a review of Shakespeare's sonnets by Stefan George , which he wrote in a torch in 1932 with the essay Da Vinci Code or Atonement to Shakespeare? panned ("Findings hopeless. Deadwood every line"), he composed the sonnets himself. He has also edited translations of several plays by Shakespeare (including Timon of Athens , King Lear , Macbeth ) and published seven of them in book form.

The lectures

Kraus gave his first lecture from his own writings on January 13, 1910 at the “Verein für Kunst” in Berlin. The response was such that the man who was persistently hushed up in Vienna considered moving to Berlin. But even in Vienna, his lectures met with the interest of the audience, which prevented him from moving to Berlin. In this way Kraus went from being a poet to being a reader.

In his lectures from his own and other people's writings (including William Shakespeare, Johann Nestroy , Jacques Offenbach ) he fascinated his audience with his power of speech and personality. He himself wrote:

“I must unite them all that

I do not accept individually.

From a thousand that each mean something,

I make a sentient mass.

Whether one or the other praises me

does not matter for the effect.

Everyone complains in the dressing room,

you were defenseless in the hall! "

In fact, with exactly 700 lectures he achieved the greatest impact with his audience, as Elias Canetti confesses in his autobiographical work The Torch in the Ear . He not only had the rhetorical tools, but also a range of variations in characterizing and portraying down to the last detail through all nuances, dialects and accents.

As much as his appearance captivated the audience, Kraus had stage fright before his performances and forbade any disturbance, including taking photos.

Small excerpts from his lectures were preserved through the use of tapes by amateurs, in some cases also through some Austrian and German radio stations. In addition, in 1934 Karl Kraus was captured on sound film by an amateur at one of his lectures.

Karl Kraus gave his 700th and last lecture on April 2, 1936 in the Vienna Konzerthaus .

Friend and foe

Funded Authors

The authors sponsored and supported by Karl Kraus included Peter Altenberg and others, the poet Else Lasker-Schüler, whom he held in high regard, and the poet Georg Trakl , who wrote a short, lyrical characterization of his patron:

- White high priest of truth

- Crystal voice in which God's icy breath dwells,

- Angry magician,

- The warrior's blue armor rattles under a flaming coat.

The torch printed in their early years - before almost exclusively Kraus's works were printed in it - moreover also u posts. a. by Houston Stewart Chamberlain , Albert Ehrenstein , Egon Friedell , Karl Hauer , Detlev von Liliencron , Adolf Loos , Erich Mühsam , Otto Soyka , August Strindberg , Frank Wedekind , Franz Werfel and Oscar Wilde . Kraus later fell out with some of these authors, especially Werfel.

"Errands"

Karl Kraus worked by messing with famous contemporaries. The list of his opponents is long and illustrious: instead of many, Hermann Bahr , Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis , Moriz Benedikt , Maximilian Harden , Alfred Kerr and Johann Schober should be mentioned . They had to be big, have followers, and influence in order to exemplify the basic. Kraus acted like a court with his magazine. Four campaigns are outlined here as examples.

Maximilian Harden

Maximilian Harden published his own magazine Die Zukunft in Berlin . Originally there was friendship between Kraus and Harden; The future, also essentially an individual's mouthpiece, was in many ways a model for the torch, and Kraus had consulted with Harden before the torch started . Then, however, Kraus sought the conflict with Harden against the background of the moral processes that Kraus had passionately approached, as they were typical of the time before the First World War. Kraus dedicated a whole collection of his essays, Morality and Crime, to this type of process , in which he advocated the right of the individual to lust and to be spared from snooping around sex.

As part of the so-called Eulenburg trials against the imperial confidante Philipp Fürst zu Eulenburg and Hertefeld and Count Kuno von Moltke , who were accused of homosexual acts, Harden fought in a mud battle (including perjury was sworn and Harden was paid insult to the following pro -forma process to be able to use a testimony) against the "Hofkamarilla". Although Kraus did not have very much sympathy for the system of the German Empire itself, he was generally disgusted with the conduct of another great moral process and the methods of Maximilian Harden - with his tactics of dragging the private lives of other people into light for political goals and thereby destruction to accept their bourgeois existence - in particular. So he dedicated an entire double issue of the torch to a large accounting with Harden (Harden. An Erledigung.), In which he also endeavors to address his position on Harden as an early promoter indicated above and to justify it with his development.

The discussion with Harden also runs through the later books The Chinese Wall and Literature and Lies, as Kraus threw himself into Harden's extraordinarily screwy language, which bristled with its splendor with education and half-education and deliberately ancient expressions. Kraus called this Hardensche German “Desperanto” and published several translations from Harden in Der Fackel (“Under the Wonnemond a Borussian Sodom cheered - complain about Prussian moral depravity in May”)

Alfred Kerr

Alfred Kerr remained for Karl Kraus almost a lifelong, at least due to his inconsiderate reactions, a particularly grateful object of his "errands".

Kraus and Kerr clashed for the first time as early as 1911. Kerr was the lead author of the literary magazine Pan , edited by publisher Paul Cassirer . In 1911, the Berlin police chief von Jagow courted the actress Tilla Durieux , Cassirer's wife at the time. This affair was amicably settled by all concerned, and there was no need to touch it. Kerr, however, wanted to put pressure on von Jagow for political reasons and published the affair with private details in the Pan with Cassirer's approval . Kraus pointed out to him in the torch essays Little Pan is dead, Little Pan is still groaning and Little Pan already stinks his actions just as he did with Harden. In the following argument, Kraus attacked Kerr's entire oeuvre and doubted his literary abilities. Finally, Kerr let himself be carried away to write a "Capricho" in Kraus, which is full of personal insults and culminates in a foul mockery poem:

- Dross, living in leaves,

- Nesting, mucking, “decisive”.

- Poor wannabe! He shouts:

- "Am I a personality ...!"

Kraus, who printed the poem in the essay The Little Pan Stinks in full length in the torch , said: "It's the strongest thing I've done against the Kerr so far [...] It is my fate that the people who I want to kill die in secret. ”Kerr has done the most harm to himself with his own Capricho and has only slowly recovered from its devastating effects.

After the First World War, Karl Kraus scourged not so much the nationalists, who at least remained true to themselves, but the war poets, who seamlessly transformed themselves into democrats and pacifists and who could no longer remember earlier activities. Alfred Kerr wore his supposedly white vest particularly boldly, among other things by traveling to Paris as a representative of the reconciliation of nations, where nothing was known about his war poems:

- Is your country, Immanuel Kant,

- Overrun by the Scythians?

- With stink and noise

- stump dull swarms of steppes

- Dogs invaded the house -

- Whip them out! [...]

- Can't get us down

- Whip them so that the rags fly,

- Tsar filth, barbarian filth -

- Whip them away! Whip them away!

The democrat and pacifist Kerr proved to be extremely sensitive to evidence of his literary work during the war. He took the fact that Kraus had wrongly ascribed one of the many war poems published under a collective pseudonym (Gottlieb) to him as an opportunity to bring a libel suit against Kraus. This in turn brought a counterclaim. Kerr, although of Jewish origin himself, used the attacks by anti-Semitic associations on Kraus for the purpose of taking the allegedly anti-Semitic Berlin court against Kraus. Both lawsuits were withdrawn amicably in court as Kerr began to suspect the publicity the trial would create. Kraus called Kerr a "scoundrel" and stated that he had agreed to the settlement of the proceedings in order to be able to publish the pleadings submitted by Kerr to the court in the torch . This was done in September 1928 in a torch over two hundred pages long. Kerr is in this text commented by Kraus, not only because of the anti-Semitic swipes, not very advantageous. In the same month he announced an answer and rebuff against Kraus, from which it was said: "Will appear in 8 days". The publication date was delayed further and further - but Kerr's answer never appeared, although (if Kraus' friends remember correctly) the talented voice impersonator Kraus is said to have called Kerr anonymously again and again and asked him when the reply should be expected.

Imre Békessy

Imre Békessy , a Hungarian who received Austrian citizenship from the city of Vienna in 1923, published the daily newspaper Die Stunden in Vienna, a new type of daily newspaper for Vienna with lots of pictures, little text, lots of advertisements, a lot of gossip and little politics. For a long time Kraus did not notice the lesson because he used the so-called quality sheets for the layer that had formed. The tabloid was Kraus on the first time, the magazine as the editor Bekessy a process of two editors The Economist could choke off by threatening with the publication of a private letter of the editors. Békessy was the ideal type of a commercial editor, who not only offered donations under the palm of the hand, but had the appearance or non-appearance of an article paid for.

The lesson reacted in its own way by offering "revelations" about Karl Kraus. This ranged from the publication of a youth photo in which the retoucher gave Kraus protruding ears and a few other unsightly features, to a fictitious dispute over the inheritance of Kraus and his sister.

Kraus reacted: in June 1925 he read the text “Unmasked by Békessy”, which culminated in the call: “Out of Vienna with the villain!”, Which he repeated on later occasions on the occasion of further works and readings on Imre Békessy, which was just as popular with the public . Kraus had only a few allies; In particular, the Social Democratic Party and the Vienna Police President Johann Schober (who had promised Kraus protection) both hesitated to take action against Békessy because Békessy knew too much about them.

Békessy could not withstand the pressure of the torch : a general manager was arrested, an employee association asked its members not to buy the hour anymore, and he was exposed to an investigation into extortion. Kraus publicly called Békessy a fraudster, perjurer and extortionist and left him to prove the contrary in court. Instead, Békessy fled abroad, as it was called "to the cure", so as not to return to Vienna.

In May 1928 Kraus made Békessy and his hour the subject of his satirical drama The Insurmountable, in which Békessy appeared as Barkassy, the Viennese police chief Schober because of his role in the suppression of the July revolt, and the speculator Camillo Castiglioni . Castiglioni obtained a performance ban in Austria, so it was premiered in Dresden.

Johann Schober

Johann Schober , three-time Austrian Chancellor and then Police President of Vienna, was responsible for the bloody suppression of the July revolt of July 15, 1927: A crowd angry after the Schattendorfer judgment had infected the Palace of Justice , the police had shot at people, and around 100 people died in the process. This event is viewed controversially to this day. In the face of an angry crowd that set fire to a courthouse, Schober was expected to make a decision. Whether the order to shoot was justified and why there had to be such a high number of victims has been discussed many times since then. The scandal was not so much the order to shoot, but the bloodlust in which departments of the Vienna police organized a “target shooting” at their “opponents”. According to the eyewitness reports published in the torch , random shots were taken at passers-by, including children and bystanders who were known to be innocent.

The bourgeois government stood behind Schober, who justified himself by saying that he had done his duty, and behind his police. Kraus was outraged, drew comparisons with the World War in the torch and in Vienna posted the message addressed to Schober in large letters: "I ask you to resign". Kraus intended to corner Schober in the same way that he had succeeded with Békessy, not only with journalistic means but also with the use of the judiciary. Aside from the events of July 15, Kraus relied on Schober's commitments in the fight against Békessy, which the latter had not kept, and measures which he had not taken. Schober, according to Kraus, broke his word and had to resign.

Here Kraus miscalculated: the audience he addressed with his moral appeal hardly wanted to know anything about it. Neither did the citizens want to reveal the “rescuer from the overthrow”, nor could the Social Democrats fully support Kraus against the “workers murderer” Schober, because between them and their Schutzbund on the one hand and the home guards on the other hand there were essentially only Schober and his police. Therefore, Kraus did nothing against Schober in the result. In this case, he could not achieve the desired "settlement". In addition, a Viennese original, the so-called “ gold fountain pen king ”, had posters posted as a joke in which Schober was asked in the same wording not to “resign”.

Kraus portrayed Schober in the drama The Insurmountable as the character Wacker. Kraus put the Schoberlied , which he wrote himself, into the mouth of this Wacker , which Kraus hoped to make popular by selling it as a cheap pamphlet - in the deceptive hope that a mocking song sung in all the streets could induce Schober to resign :

- Yes this is my duty

- please don't see that.

- That would be such a thing,

- I am not doing my duty [...]

The song continues in this way (on motifs from Ub Always Faithful and Honesty and the Radetzky March ), but ends with the stanza:

- Some wretches dare to do it

- and misjudges my duty.

- But I'm not going to court

- this is not my duty!

With this, Kraus alludes to the fact that Schober did not sue him despite angry attacks.

Admired role model and figure of hatred

The sensational success of the torch - it reached a circulation of over 30,000 copies right from the start - made Karl Kraus famous and an object of admiration, imitation and envy within journalism. There were numerous imitations and competing magazines that tried to orientate themselves in the design and tone of his magazine. Examples are: in the torchlight , in the fire shrine , Don Quixote , storm! , The rabble , the scandal and torpedo (by Robert Müller ). The position that Kraus occupied in World War I again earned him numerous admirers, such as Siegfried Jacobsohn (1905 founder of the magazine Die Schaubühne ), who initially published critical articles on Kraus in his paper. Max Brod called Kraus a "mediocre head whose style rarely avoids the two bad poles of literature, pathos and pun". Arthur Schnitzler noted a "cloud of hatred" in Kraus and caricatured him as a critic Rapp in Der Weg ins Freie . Schnitzler, however, showed his respect for the last days of mankind , whose satire seemed "brilliant to the point of great" to him. The speech Zarathustra's Monkey , given by Anton Kuh on October 25, 1925 in the Wiener Konzerthaussaal , in which Kuh accused Karl Kraus of acting vanity and a logic of devaluation, and made him responsible for the hysterical and excessive attitude of his followers according to his own principles , became legendary .

effect

“When he died, he seemed to have outlived himself. Since he began to resurrect fifteen years later, we saw that he had survived and will survive us. "(Hans Weigel)

Torch and books, although originally lucrative, had become a losing business, and Kraus died almost destitute. Without exception, he had donated the proceeds from his many readings to charitable causes. The estate was barely enough to cover the cost of the funeral. He might not have been able to finance another issue of the torch. A Karl Kraus archive was brought to Switzerland just in time for 1938: what remained in Vienna was looted and destroyed. Although there is no closed estate, a large part of it is now in the Vienna Library in the City Hall .

Kraus and his time had grown apart. There was little to suggest that posterity, which had been profoundly changed by other events after his death, would show him any interest. And really: Kraus is posthumously an “insider tip” even more than during his lifetime, and his work may be recommended in literary canons from time to time . Many of his writings deal with Viennese affairs from a hundred years ago; you don't have to belong to the "educationally distant classes" to find this material uninteresting, and a complete understanding is only possible in the context of contemporary history and the torch run - someone from the English-speaking area called it idiosyncratic Austrian , whose readers also because of the language barrier be prevented.

And yet the work is timeless. It finds readers who are drawn to Kraus 'mastery of the satirical form - a satire that lives from language in such a way that Kraus' works are very difficult to translate. Even after a century, many of the torch's issues are not settled. The fact that Kraus did not subordinate himself to any ideology, drawer or party, rather stepped on the toes of (almost) everyone, limited his popularity during his lifetime; he could neither be the pillar saint of the revolution nor of the reaction, his writings were not suitable for either the Bible study group or the synagogue, and neither patriarchs nor emanciers could fully agree with him.

So now as then, Kraus' work is little known compared to its importance. You have to consider, however, that Kraus is one of the very few (like Kurt Tucholsky, for example ) who managed to reach the top of the writing table with journalistic work and whose works on daily events from a long time past are still valued and read today. In fact, most of his opponents are actually just today - except as a footnote in history books - known because of the torch completed were. But this is what makes Kraus so controversial to this day: that he was immoderate in “getting things done” and hardly any contemporary, no matter how important, could escape his campaigns. In 1984 Hellmut Andics wrote of Kraus' “Demoliertaktion an literary monuments” with the torch as the “executive organ of a cultural moral police, and with the mentality of a beating police officer, Karl Kraus also took action against the intellectual underworld. As the prosecutor, judge and executioner in one person, he himself decided what “underworld” was. ”Even in death Kraus did not hope for peace, on the contrary:

- I remain connected to the words

- against which I defend myself of the spirit. [...]

- I boldly tear myself away from the lazy peace

- to have nothing but the dead silence [...]

- The fear of death is that nature will bring me

- once for all living horror

- That eternal rest cannot be trusted.

- I want to suffer, love, hear, see:

- eternally restless that the work may succeed!

He has had a great impact on Austrian literature to the present day. Representative of this is the attitude of Elias Canetti, who as a Goethe reader freed himself from the unconditional commitment to Kraus as a role model, but then changed his very critical attitude after the publication of Kraus' correspondence with Sidonie Nádhérny in the 1970s. In literary criticism in Austria, Edwin Hartl consistently referred to Karl Kraus as the outstanding benchmark for decades, as has recently also Wilhelm Hindemith in Germany. The essayist Erwin Chargaff describes Karl Kraus in an interview with the biographer Doris Weber as his "only real teacher". The American writer Jonathan Franzen also joins the ranks of Kraus recipients .

Honors

In 1970 Karl-Kraus-Gasse in Vienna- Meidling was named after Kraus. On April 26, 1974, the Austrian Post issued a commemorative stamp on his 100th birthday (4 Schillings, purple-red. Michel No. 1448). On the same occasion, the Vienna City Library organized a Karl Kraus exhibition in the archive of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna from May 20 to June 30, 1974.

Publications

Book editions published during his lifetime

- The demolished literature. 1897.

- Morality and crime. 1908 textlog.de .

- Proverbs and contradictions. 1909.

- The Great Wall of China. 1910 1914 edition by Austrian Literature Online (ALO); 4th edition online in Chicago .

- Words in Verse (1916–1930):

- The last days of humanity. 1918.

- Last Judgment. 1919.

- Selected poems. 1920 online in Chicago .

- The end of the world through black magic. 1922 textlog.de .

- Literature. 1921 online in Chicago .

- Dream piece. 1922 1923 edition in Chicago .

- Cloud Cuckoo Land. 1923 online in Chicago .

- The insurmountable. 1927 Edition 1928 at ALO .

- Literature and lies. 1929 at ALO .

- Shakespeare's sonnets. 1933

Posthumous editions

- The language. Prepared by Kraus, final editing by Philipp Berger, 1937.

- The third Walpurgis Night. Edited by Heinrich Fischer 1952, ISBN 3-518-37822-8 . Online version

The torch (reprints)

- Kösel-Verlag 1968–1970, also as paperback 1976

- Two thousand and one 1977 (here reduced in size).

Work editions

Karl Kraus: Works (1954–1970)

Published by Heinrich Fischer

- The Third Walpurgis Night (the first edition subsequently became part of the work edition)

- The language. 2., ext. Reprint, 1954

- Taken at your word. 1955 (contains: sayings and contradictions, Pro domo et mundo, night )

- Reflection of the torch. Glossary from the torch 1910–1932, with annotations, 1956

- The last days of humanity. Tragedy in five acts with prelude and epilogue (version from 1926), 1957

- Literature and lies. 1958

- Words in verse. 1959

- The end of the world through black magic. 1960

- Immortal Joke, glosses from 1908–1932, 1961

- With great respect. Letters from the Torch Publishing House. 1962

- Morality and crime. 1963 (also as vol. 191 of the series " The Books of the Nineteen ", Nov. 1970)

- The Great Wall of China. 1964

- Last Judgment. 1965

- Dramas. 1967

- Supplementary Volume: Shakespeare's Dramas. Edited by Karl Kraus, 1970 (2 volumes)

- Supplementary volume: Shakespeare's sonnets. Adaptation by Karl Kraus, 1964

(All in Kösel- Verlag with the exception of 11-14 from Langen Müller Verlag . Volumes 1-10 also as paperback in cassette, around 1974).

Karl Kraus: Selected Works (1971–1978)

- Grimaces. Selection 1902–14, edited by Dietrich Simon with the assistance of Kurt Krolop and Roland Links based on the works published by Heinrich Fischer and the magazine Die Fackel, 1971 (online)

- In this great time. Selection 1914–25, edited by Dietrich Simon with the assistance of Kurt Krolop and Roland Links based on the works published by Heinrich Fischer and the magazine Die Fackel, 1971 (online)

- Before Walpurgis Night. Essays 1925–33, edited by Dietrich Simon with the assistance of Kurt Krolop and Roland Links based on the works published by Heinrich Fischer and the magazine Die Fackel, 1971 (online)

- Aphorisms and poems. Selection 1903–33, edited and with an afterword by Dietrich Simon, 1974

- The last days of humanity. Tragedy in five acts with prelude and epilogue. Edited by Kurt Krolop in collaboration with a group of editors led by Dietrich Simon, 1978 (with commentary)

All volumes in Verlag Volk und Welt

Karl Kraus: Writings (1986–1994)

Edited by Christian Wagenknecht , Suhrkamp- Verlag

- Morality and crime. 1987, ISBN 3-518-37811-2 .

- The Great Wall of China. 1987, ISBN 3-518-37812-0 .

- Literature and lies. 1987, ISBN 3-518-37813-9 .

- The end of the world through black magic. 1989, ISBN 3-518-37814-7 .

- Last Judgment I. 1988, ISBN 3-518-37815-5 .

- Last Judgment II. 1988, ISBN 3-518-37816-3 .

- The language. 1987, ISBN 3-518-37817-1 .

- Aphorisms. Proverbs and contradictions. Pro domo et mundo. At night. Suhrkamp 1986, ISBN 3-518-37818-X .

- Poems. 1989, ISBN 3-518-37819-8 .

- The last days of humanity. Tragedy in five acts with prelude and epilogue. 1986, ISBN 3-518-37820-1 .

- Dramas. Literature / Dream play / Cloud cuckoo home / Dream theater / The insurmountable. 1989, ISBN 3-518-37821-X .

- Third Walpurgis Night. 1989, ISBN 978-3-518-37822-9

- Theater of Poetry. Jacques Offenbach. 1994, ISBN 3-518-37823-6 .

- Theater of Poetry. Nestroy. Time stanzas. 1992, ISBN 3-518-37824-4 .

- Theater of Poetry. William Shakespeare. 1994, ISBN 3-518-37825-2 .

- The hour of judgment. Articles 1925–1928. 1992, ISBN 3-518-37827-9 .

- Bread and lies. Articles 1919-1924, 1991, ISBN 3-518-37826-0 .

- Over and over. Articles 1929–1936. 1993, ISBN 3-518-37828-7 .

- The catastrophe of phrases. Glosses 1910–1918. 1994, ISBN 3-518-37829-5 .

- Cannonade on sparrows. Glosses 1920–1936. Shakespeare's sonnets. Re-seal. 1994, ISBN 3-518-37830-9 .

As an electronic resource: Directmedia Publishing Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-89853-556-4 .

Other relevant issues

- Karl Kraus: Heine and the consequences. Writings on literature. Edited and commented by Christian Wagenknecht and Eva Willms. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-8353-1423-8 .

- Shakespeare's sonnets. Re-seal. Diogenes, 1977, ISBN 3-257-20381-0 .

- The Great Wall of China. With eight illustrations by Oskar Kokoschka . Insel, 1999, ISBN 3-458-19199-2 .

- The last days of humanity. Stage version by the author. Edited by Eckart Früh . With drawings by Georg Eisler and an essay by Eric Hobsbawm . Frankfurt / Main: Gutenberg Book Guild 1994.

Correspondence

- “Remembering the one day in Mühlau”. Karl Kraus and Ludwig von Ficker. Letters, documents 1910–1936. Edited by Markus Ender, Ingrid Fürhapter and Friedrich Pfäfflin. Wallstein, Göttingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-8353-3151-8 .

- "How geniuses die". Karl Kraus and Annie Kalmar. Letters and Documents 1899–1999. Edited by Friedrich Pfäfflin and Eva Dambacher. Wallstein, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-89244-475-7 .

- Karl Kraus - Mechtilde Lichnowsky: Letters and Documents: 1916–1958, edited by Friedrich Pfäfflin and Eva Dambacher, in collaboration with Volker Kahmen. German Schiller Society Marbach am Neckar 2000, ISBN 3-933679-23-0 ; “Revered Princess”: Karl Kraus and Mechthilde Lichnowsky, letters and documents, 1916–1958, Wallstein Verlag , Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-89244-476-5 .

- Karl Kraus: Letters to Sidonie Nádherný von Borutin 1913–1936. Edited by Friedrich Pfäfflin, 2 volumes. Wallstein, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-89244-934-1 .

- "You are dark with gold." Kete Parsenow and Karl Kraus. Letters and documents. Edited by Friedrich Pfäfflin. Wallstein, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8353-0984-5 .

- Reinhard Urbach : Karl Kraus and Arthur Schnitzler. A documentation. In: literature and criticism. 49, October 1970, pp. 513-530.

- Karl Kraus - Otto Stoessl: Correspondence 1902–1925. Edited by Gilbert J. Carr. Deuticke, Vienna 1996.

- Enemies in droves. A real pleasure to be there: Karl Kraus - Herwarth Walden correspondence 1909–1912. Edited by George C. Avery. Wallstein, Göttingen 2002, ISBN 3-89244-613-X .

- Karl Kraus - Frank Wedekind. Correspondence 1903 to 1917. Edited and commented on by Mirko Nottscheid. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8260-3701-6 .

- Karl Kraus - Franz Werfel. A documentation. Compiled and documented by Christian Wagenknecht and Eva Willms, Wallstein, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8353-0983-8 .

- Karl Kraus - Kurt Wolff: Between Judgment Day and Last Judgment. Correspondence 1912–1921. Edited by Friedrich Pfäfflin. Wallstein, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-8353-0225-9 .

Documents

- Peter Altenberg : Your unhappy Peter: Letters to Karl Kraus. In: Andrew Barker, Leo A. Lensing: Peter Altenberg: Recipe to see the world. critical essays, letters to Karl Kraus, documents on reception, book titles. (= Studies on the Austrian literature of the 20th century. Volume 11). Braumüller, Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-7003-1022-6 , pp. 209-268.

- Hermann Böhm (Ed.): Karl Kraus contra ... The trial files of the Oskar Samek law firm. 4 volumes. Vienna 1995–1997.

-

Jonathan Franzen : The Kraus Project. Essays. Fourth Estate, London 2013, ISBN 978-0-00-751824-1 .

- Edited and annotated by Jonathan Franzen , with Paul Reitter and Daniel Kehlmann : The Kraus Project. Essays by Karl Kraus. Translated from the English by Bettina Abarbanell . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-498-02136-8 .

- Karl Kraus: Even dwarfs cast long shadows: sayings and contradictions. Aphorisms , Marix, Wiesbaden 2013, ISBN 978-3-86539-304-3 .

- Anton Kuh : The monkey of Zarathustra. In: Luftlinien. Features, essays and journalism. Edited by Ruth Greuner , Verlag Volk und Welt, Berlin 1981. (Kuh's impromptu speech of October 25, 1925 against Kraus.)

Sound documents with Karl Kraus

- Shellac records (electro-acoustic recordings) from the company “Die Neue Truppe” (1930/31): Karl Kraus reads “Das Schoberlied” (No. 141, listening ) and “Das Lied von der Presse” (No. 142, listening ) - “The Ravens” from “The Last Days of Mankind” (No. 143, listening ) - “Fear of Death” (No. 144, listening ) - “The Cross of Honor” (No. 158, listening ) - “Colorful incidents” (No. 159, listening ) - “Youth” (No. 160, listening ).

- Karl Kraus reads from his writings. Preiserrecords, 93017, 1989 (CD). Recordings of the “New Troop” (1930/31) (except: A. Polgar's obituary (recorded on January 8, 1952) and “Reklamefahrten zur Hölle” (soundtrack from the 1934 film)). Contains: Obituary for Karl Kraus, spoken by Alfred Polgar. - Kraus reads and sings: “The song from the press”. - "The Cross of Honor". - "Colorful events". - "Youth". - "The Schoberlied". - "Away with it!" - "To eternal peace". - "The Ravens". - "Advertising trips to hell". - "Fear of Death".

- Karl Kraus reads. Preiserrecords, 90319 (CD). Contains recordings from 1930 and 1931. Goethe: “Eos and Prometheus” from “Pandora”. - Shakespeare: Four fragments from “Timon of Athens”. - J. Offenbach: Metella's letter from "Paris Life". - J. Offenbach: "At table", from "The babbler from Saragossa". - F. Raimund: Scenes from Act 1 of "The Alpine King and the Misanthrope".

reception

Exhibitions

- Karl Kraus, German Literature Archive Marbach . Catalog: Friedrich Pfäfflin…, Marbach am Neckar ( Schiller National Museum ) 1999, (Marbach Catalogs; 52), ISBN 3-933679-19-2 .

- “What We Kill” - “The Torch” by Karl Kraus, Jewish Museum Vienna . Catalog: Heinz Lunzer, Victoria Lunzer-Talos, Marcus Patka (Ed. On behalf of the Jewish Museum of the City of Vienna) 1999, ISBN 3-85476-024-8 .

- Katharina Prager (ed.): Spirit versus Zeitgeist: Karl Kraus in the First Republic. Vienna, Metroverlag 2018, ISBN 978-3-99300-328-9 .

Movie

- Karl Kraus: From my own writings. Sound film, 18 min., Prague-Paris-Filmgesellschaft, Prague, 1934. Production manager: Albrecht Viktor Blum (Prague). First performed in Vienna for Karl Kraus' 60th birthday in June 1934. Original in the Vienna City and State Archives, Vienna. Published as a VHS video within the material accompanying the Karl Kraus exhibition at the German Literature Archive in Marbach, 1999. Contains: “To Eternal Peace”. - "The Ravens". - "Advertising trips to hell". - "Away with it!"

- In sight: the last days of mankind. A film about Karl Kraus, the war and the journalists. Documentary, 58 min., Director: Ivo Barnabò Micheli , production: WDR , first broadcast in 1992.

- Karl Kraus. The brightest inventions are quotations. Documentary, 45 min., Script and direction: Florian Scheuba and Thomas Maurer, production: SWR , first broadcast: December 17, 2006.

Graphic novel

- The last days of humanity. A graphic novel based on Karl Kraus. Edited by Reinhard Pietsch, illustrated by David Boller. Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-8316-4372-1 .

literature

- Theodor W. Adorno : Morality and criminality. To the eleventh volume of the works of Karl Kraus. In: Th.WA: Gesammelte Schriften. Volume 11, Frankfurt am Main 1974, pp. 367-387.

- Gerhard Amanshauser : Reading. Aigner, Salzburg 1991, pp. 26, 78, 107.

- Helmut Arntzen : Karl Kraus and the press. (= Literature and press. Karl Kraus studies. Volume 1). Munich 1975, ISBN 3-7705-1272-3 .

- Helmut Arntzen: Kraus, Karl. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-00193-1 , pp. 694-696 ( digitized version ).

- Hermann Bahr, Arthur Schnitzler: Correspondence, records, documents 1891–1931. Edited by Kurt Ifkovits, Martin Anton Müller. Göttingen: Wallstein 2018, ISBN 978-3-8353-3228-7 Three letters to Schnitzler

- Walter Benjamin : Karl Kraus. In: Ders .: Collected writings. Volume II / 1, Frankfurt am Main 1977, pp. 334-367.

- Elias Canetti : Karl Kraus - School of Resistance. In: Power and Survival. LCB, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-920392-36-1 .

- Jens Malte Fischer : Karl Kraus. Studies on the 'theater of poetry' and cultural conservatism. Kronberg 1973.

- Jens Malte Fischer: Karl Kraus. Stuttgart 1974.

- Jens Malte Fischer: Karl Kraus: The opponent. Biography, Zsolnay Verlag, Vienna 2020, 1104 pp., ISBN 978-3-552-05952-8 .

- Jonathan Franzen : The Kraus Project. HarperCollins UK 2013.

- Mirko Gemmel: The Critical Viennese Modernism. Ethics and aesthetics. Karl Kraus, Adolf Loos, Ludwig Wittgenstein. Parerga, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-937262-20-2 .

- Wolfgang Hink: "The torch." Ed. Karl Kraus. Bibliography and index. 2 volumes Munich 1994.

- Youssef Ishagpour: Mass and Power in Elias Canetti's Work. In: John Pattillo-Hess (Ed.): Death and Metamorphosis in Canetti's Mass and Power. Canetti Symposium of the Kunstverein Wien, Löcker, Wien 1990, pp. 78–89.

- Joachim Kalka: Slovenian organ organ. A poem by Karl Kraus. Ulrich Keicher, Warmbronn 2011, without ISBN.

- Werner Kraft : Karl Kraus: Contributions to the understanding of his work. Müller, Salzburg 1956.

- Werner Kraft: The yes of the naysayer: Karl Kraus and his spiritual world. edition text + kritik , Munich 1974, ISBN 3-415-00369-8 .

- Benjamin Lahusen: Philanthropist and Misodem. Karl Kraus, the people and democracy: an attempt on a current occasion. In: myops . 35, 2019, pp. 15-24.

- Reinhard Merkel : criminal law and satire in the work of Karl Kraus. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1998, ISBN 3-518-28945-4 .

- Michael Naumann : The dismantling of an upside-down world. Satire and political reality in the work of Karl Kraus. List, Munich, 1969 (also Diss. Phil. Ludwig Maximilians University Munich ).

- Alfred Pfabigan : Karl Kraus and socialism. Vienna, 1976.

- Friedrich Pfäfflin (ed.): The "torch" run. Bibliographic directories. German Schiller Society , Marbach 1999, ISBN 3-933679-24-9 .

- Friedrich Pfäfflin (Ed.): Close up. Karl Kraus in reports of companions and adversaries. Janowitz Library, Wallstein, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8353-0304-1 .

- Sigurd Paul Scheichl and Christian Wagenknecht (eds.): Kraus-Hefte. Total 72 booklets, Ed. Text + criticism, München 1972–1994.

- Paul Schick : Karl Kraus. Rowohlt Bild Monographien, Reinbek 1986, ISBN 3-499-50111-2 .

- Paul Schick: Kraus Karl. In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 4, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1969, pp. 230–232 (direct links to p. 230 , p. 231 , p. 232 ).

- Gerald Stieg : The burner and the torch. A contribution to the history of the impact of Karl Kraus. Brenner Studies Volume 3, ed. by Eugen Thurnher and Ignaz Zangerle , Müller, Salzburg 1976, ISBN 3-7013-0530-7 .

- Jochen Stremmel: Third Walpurgis Night - About a text by Karl Kraus. Bouvier, Bonn 1982.

- John Theobald: The Paper Ghetto. Karl Kraus and Anti-Semitism. New York 1996.

- Edward Timms : Karl Kraus. Satirist of the Apocalypse. Life and work 1874–1918. Deuticke, Vienna 1986 (as paperback: Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1999, ISBN 3-518-39495-9 ).

- Edward Timms: Karl Kraus. The post-war crisis and the rise of the swastika. (= Encyclopedia of Viennese Knowledge, series portraits. Volume V). Publishing House Library of the Province , Weitra 2016, ISBN 978-3-99028-499-5 .

- Hans Veigl : Karl Kraus. The demolished literature. Edited and commented by Hans Veigl (= Allotria. 1). Austrian Cabaret Archive, Graz 2016, ISBN 978-3-9501427-5-4 .

- Christian Wagenknecht: The pun with Karl Kraus. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , Göttingen 1965.

- Hans Weigel : Karl Kraus or The Power of Powerlessness. dtv , Munich 1968, ISBN 3-423-00816-4 .

- Martin Weiß: Kraus, Karl. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 15, Bautz, Herzberg 1999, ISBN 3-88309-077-8 , Sp. 826-842.

more publishments

- Wilhelm Hindemith: Karl Kraus' "Last Days of Mankind": Which command does media power obey? In: Badische Zeitung online. July 28, 2014. Retrieved November 21, 2014

Web links

- Karl Kraus Online , an online project of the Vienna Library and the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute (focus: the reader)

- Digital edition of the torch with full text search of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (AAC)

- Karl Kraus in the Vienna History Wiki of the City of Vienna

- Works by Karl Kraus in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Literature by and about Karl Kraus in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Karl Kraus in the German Digital Library

- Holdings in the catalog of the Austrian National Library

- Entry on Karl Kraus in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- Sigurd Paul Scheichl: Portrait module on Karl Kraus at litkult1920er.aau.at , a project of the University of Klagenfurt

- Karl Kraus: Viennese places. Biography and topography of Karl Kraus

- Karl Kraus. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Works by Karl Kraus at textlog.de

- Karl Kraus' apartment immediately after his death in 1936. Literaturhaus - Exhibition 2006; accessed on April 15, 2017.

- ub.fu-berlin.de ( Memento from January 29, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Link collection of the University Library of the Free University of Berlin

- Markus Murauer: Karl Kraus and Judaism. In: aurora-magazin.at

- “I was seldom in love, always hated.” (Life & Work, Selected Aphorisms) In: Glanz @ Elend - magazine for literature and contemporary criticism.

- Incitement to rediscover Karl Kraus (series of articles by Richard Schuberth in Augustin magazine)

- Photo gallery for Karl Kraus

- Karl Kraus - Last Judgment. Polemics against the war. Online exhibition, 2014

- Advertising Drives To Hell Online version of the 1921 text

swell

Texts by Kraus are quoted as far as possible from the edition: C. Wagenknecht (Ed.): Karl Kraus: Schriften. (= Suhrkamp Taschenbuch. 1311-1322). Frankfurt am Main 1989.

- ↑ Georg Gaugusch : Who once was. The upper Jewish bourgeoisie in Vienna 1800–1938. Volume 1: AK . Amalthea, Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-85002-750-2 , pp. 1545-1548.

- ^ Alfred Pfabigan : Karl Kraus / Hermann Bahr - revisited . In: Hermann Bahr - Austrian critic of European avant-garde . Peter Lang, 2014, ISBN 978-3-0351-9573-6 , pp. 83-98 .

- ^ Proverbs and contradictions. In: Volume 8 (Aphorisms). P. 45. See Veith Trial. In: Volume 2 (The Great Wall of China). P. 32: "Immorality lives in peace until envy pleases morality to draw attention to it, and the scandal only begins when the police put an end to it."

- ↑ Joachim W. Storck, Waltraud, Friedrich Pfäfflin (eds.): Rainer Maria Rilke - Sidonie Nádherný von Borutin: Correspondence 1906–1926. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-89244-983-X .

- ↑ In this great time. In: Volume 5 (Weltgericht I), p. 9. Cf. Die Fackel. No. 404, December 1914, p. 1.

- ↑ Eckart Early in: Karl Kraus and France. In: Austriaca. Relations franco-autrichienne (1870–1970). Rouen 1986, pp. 273f. ( limited preview in Google Book search)

- ↑ nobelprize.org

- ^ Schick: Karl Kraus. P. 136; Letters to Sidonie Nádherný from Borutin. Volume 2, Notes. dtv, Munich, 1974, p. 404.

- ↑ V. Retrieved October 2, 2019 .

- ^ Felix Czeike: Historical Lexicon Vienna. Volume 3, p. 598 f.

- ↑ Stefan Zweig; The world of yesterday. Memories of a European. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1986, p. 127.

- ↑ Thomas Mann: About Karl Kraus. S. Fischer Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-10-400396-2 . limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Patricia Alda: Karl Kraus' relationship to journalism. Books on Demand, 2002, ISBN 3-8311-4651-9 , p. 83. Limited preview in Google Book Search

- ↑ Weigel: Kraus or the power of impotence. P. 128.

- ↑ The disaster of phrases. Glosses 1910–1918. Suhrkamp 1994, Frankfurt am Main, p. 176.

- ^ Albert Fuchs: Spiritual currents in Austria 1867-1918. Globus, Vienna 1949; contained in the 1984 reprint (Löcker): Albert Fuchs - Ein Lebensbild, p. XXIV.

- ^ Friedrich Torberg : The heirs of Aunt Jolesch. dtv, p. 44.

- ↑ Friedrich Torberg: Biased as I am. Langen Müller, p. 81.

- ↑ for an exemplary list of these and other designations cf. Weigel: Kraus or the power of impotence. P. 125.

- ↑ a b Weigel: Kraus or the power of impotence. P. 125.

- ↑ The song about the press in literature or One will see there. In: Volume 11 (Dramas), p. 57.

- ↑ A necessary chapter. In: Volume 3 (literature and lies). P. 144.

- ↑ Weigel: Kraus or the power of impotence. P. 128 f.

- ↑ for example: Albert Fuchs : Geistige Strömungen in Österreich 1867-1918. Globus, Vienna 1949, p. 272.

- ↑ Jacques Le Rider : The end of the illusion. Viennese modernism and the crises of identity. Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-215-07492-3 .

- ↑ a b quot. after: history with a kick, 5/93: Palestine / Israel. P. 45 (author cannot be determined), ISSN 0173-539X

- ↑ He's a Jew. In: Volume 4 (Fall of the World through Black Magic). P. 327 ff.

- ↑ Volume 12 (Third Walpurgis Night). P. 159.

- ↑ Die Fackel, No. 922, February 1936, p. 112.

- ↑ Die Torch No. 557-560 January 1921 archive.org p. 45 f.

- ↑ Volume 9 (Poems), p. 639. Cf. Die Fackel No. 888, October 1933, p. 4.

- ^ Schick: Karl Kraus. P. 129; s. a. Bert Brecht: "On the meaning of the ten-line poem in the 888th number of the torch" ( Memento from September 20, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) (October 1933)

- ↑ Volume 12 (Third Walpurgis Night). P. 41.

- ↑ Why the torch does not appear. In: Die Fackel, No. 890–905, end of July 1934, p. 10.

- ↑ Die Fackel, No. 885–887, end of December 1932, p. 61.

- ↑ The reader. In: Words in Verses III, Volume 9 (Poems), p. 144.

- ^ Karl Kraus reads from his own writings. Recordings from 1930–1934. Preiser Records, 1989, ISBN 3-902028-22-X .

- ^ Translation from Harden. In: Volume 3 (literature and lies). P. 81.

- ↑ Little Pan is dead , Little Pan is still groaning , Little Pan already stinks at textlog.de

- ↑ Karl Kraus - Literature: Little Pan still stinks - The Kerr case. In: textlog.de. July 8, 1911, accessed January 5, 2015 .

- ^ The hour of the court, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1992, p. 174.

- ↑ in: Volume 11 (dramas) p. 306f. or 395 (with score)

- ↑ Martina Bilke: Contemporaries of the "torch". Vienna 1981, p. 109ff, summary p. 150f.

- ↑ Bilke (1981) pp. 153–160f, around the mid-1920s, however, there was again a distancing.

- ↑ Bilke (1981), p. 166.

- ↑ Bilke (1981), p. 196.

- ^ Anton Kuh: Luftlinien. Vienna 1981, p. 153ff.

- ↑ Weigel, p. 16.

- ↑ Lueger time. Black Vienna until 1918, Vienna & Munich (Jugend & Volk), 1984, p. 278 restricted preview in the Google book search

- ↑ Fear of death in words in verse VI. In: Volume 9 (Poems), p. 435.

- ↑ Doris Weber: Against the genre intoxication. A meeting of the century. Publik-Forum, Oberursel 1999.