Angevin Empire

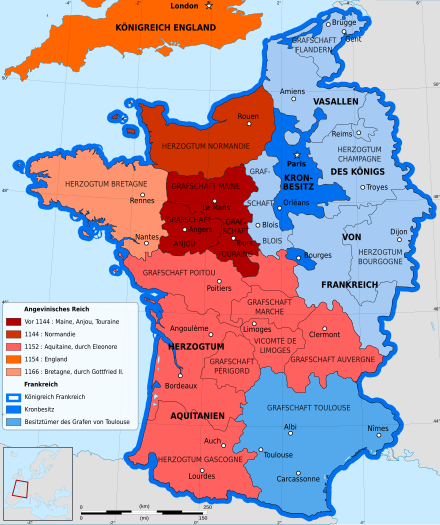

The Angevin Empire ( English Angevin Empire , French Empire angevin or Empire Plantagenêt ) is a modern term for the extensive territorial possessions of the House of Plantagenet from around 1150 to the middle of the 13th century. The property mainly comprised the entire western half of France and the Kingdom of England .

Name of the empire

The French adjective angevin ("from Anjou") describes the inhabitants and their spoken dialect from the French Anjou countryside around the main town of Angers . In the ancient times there moved the Celtic tribe of the Andegaven , after which the medieval Count of Anjou in the former Latin either comes Andecavorum ( "Count of Anjou") or comes Andegavensis called ( "Count of Anjou").

The Anjou was the ancestral home of the Plantagenets, which is why this family is often referred to as the first Angevin Dynasty in England , in distinction to the second and third Angevin dynasties . The term Angevin Empire itself is a word created in recent historical research and was first used by the British historian Kate Norgate in her work England under the Angevin Kings , published in 1887 . Here, however, the use of the term is Empire (Empire, Empire) among historians controversial because during the Middle Ages in the narrow constitutional sense only the Holy Roman Empire ( Sacrum Roman Empire was to be understood) as an "empire". Especially since the Plantagenets never had an imperial title ( imperator , augustus ) that would have legitimized their rule over their country complex.

Rather, the “Angevin Empire” consisted of a union of several legal titles within the Plantagenets family. The highest title they held was that of King of England ( regi Angliæ ), with which, however, rulership rights were exclusively connected in England, which is why the "Angevin Empire" cannot be referred to as an "English Empire" either how the mainland areas were English territory. For their areas on the French mainland, the Plantagenets had the respective legal titles that established their rule there.

In France, instead of an Angevin, they speak of the Empire Plantagenet .

Emergence

The Counts of Anjou were French feudal princes who had become the most powerful vassals of the French king by the middle of the 12th century. In addition to their home country Anjou, which was located in the lower Loire Valley around Angers , they already controlled the neighboring areas around Tours and Le Mans (together called Grand Anjou ). The Angevin Empire owed its origin to two marriages of the Count's house: first in 1128 that of Count Gottfried V of Anjou , who was already called Plantagenêt " gorse " by contemporaries - perhaps after his helmet - with Mathilde , who was due to the previous marriage with the Roman-German Emperor Heinrich V. "Empress", heiress of the Anglo-Norman Empire. This marriage brought the Plantagenet House , established by the two, the right to Normandy , which was implemented in 1144, and to the Kingdom of England. Heinrich II. Kurzmantel , the couple's son, married the Duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152 , with which her extensive property, which encompassed almost the entire south of France, came to the family. Heinrich was also able to ascend the English throne in 1154 after his rival Stephan von Blois had died.

Acquis and related vassals

- Duchy of Normandy (1144)

-

Duchy of Aquitaine (1152)

- Poitou (ducal domain)

- Saintonge (ducal domain)

- Angoulême county

- County of Périgord

- County of La Marche

- Auvergne county

- Vice-counties of the Limousin ( Limoges , Turenne , Comborn , Ventadour , Rochechouart )

- Vice-counties of Poitou ( Châtellerault , Thouars , Brosse )

- lower berry ( Châteauroux , Issoudun )

- County of Toulouse (vassal to Aquitaine since 1173)

(The county of Bigorre was a vassal of Aragón since 1082, the county of Comminges a vassal of Toulouse since 1144.)

-

Duchy of Gascony (1152)

- Bordelais (ducal domain)

- Agenais (ducal domain)

- Armagnac county

- County of Fézensac

- Astarac county

- various vice counties such as Lavedan , Dax , Tartas etc.

- Vice-county of Béarn (until 1154, then to Aragón)

-

Kingdom of England (1154)

- Kingdom of Scotland (vassal to England since 1157)

- Welsh principalities (vassal to England since 1163)

-

Duchy of Brittany (1166, previously vassal to Normandy)

- Nantais (ducal domain)

- Rennetais (ducal domain)

- Vannetais (ducal domain)

- County of Penthièvre

- Vice County of Rohan

-

Eastern Ireland (1171)

- Western Irish petty kings

Family table of the Plantagenets

|

Gottfried V of Anjou (1113–1151) |

Mathilde "the Empress" (1102–1167) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Heinrich II. Short coat (1133–1189) |

Eleanor of Aquitaine (1123–1204) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Henry the Younger (1155–1183) |

Richard the Lionheart (1157–1199) |

Gottfried of Brittany (1158–1186) |

Johann Ohneland (1167-1216) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arthur of Brittany (1187-1203) |

Henry III. (1207-1272) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kings of England until 1485 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Character of the empire

The Angevin Empire was not a united state structure, it was rather a combination of several territories that were ruled in personal union by a ruler. This means that there was no unifying imperial ideology as in the Holy Roman Empire , there was also no uniform imperial administration nor a special feeling of belonging among the subjects of the respective parts of the empire. Rather, each part of the empire had its own administration and its own legal customs. The ruling power was also different in the respective territories. If, for example, rule in England or Normandy was strongly geared towards the person of the king or duke by means of a centralized administration, in Aquitaine or Brittany it was only poorly developed and primarily dependent on the loyalty of powerful vassals.

Another defining feature of the Angevin Empire that contributed significantly to its downfall was the feudal affiliation of its continental territories to the French kingdom. That is, the Plantagenets were vassals of the French kings for these areas, to whom they were obliged to be allegiance. It is not uncommon for the French kings of the Capetian dynasty to use their feudal position, which was superior to the Plantagenets, to weaken them, because the kings of France had only a negligible area compared to the Plantagenets, the crown domain , to which they had direct access. So rule over their kingdom also depended on the loyalty of their vassals to them. The Plantagenets in their abundance of power represented a constant threat potential for them. The establishment of a strong royal power in France could ultimately only go through the smashing of the territorial conglomerate of the Plantagenets.

history

Consolidation under Heinrich II. Short coat

Under Heinrich II. Kurzmantel the Angevin Empire reached its greatest territorial extent. In 1151 he was able to take over the Duchy of Normandy from his father in addition to the family estates around Anjou, Maine and Touraine. Together with his father, shortly before his death, he took the oath of feudal oath to the French King Louis VII for these areas in Paris . Heinrich began a relationship with Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine , which eventually led to her marriage in the same year after Eleanor divorced her first husband. This unified all the main areas of the Angevin Empire in this couple, but at the same time marked the beginning of the rivalry between the French king and Eleanor's ex-husband and the Plantagenet. The wedding alone happened without the consent of King Ludwig VII, as the liege lord of both spouses. The conflict eased on February 5, 1156 in the Vexin , when Heinrich paid homage to Ludwig VII for all land holdings, including those of his wife.

After King Stephen's death in 1154, Heinrich succeeded him in the Kingdom of England. In his capacity as the English king, he was able to gain supremacy over the British island. The Scottish king paid homage to him in 1157 and the Welsh princes in July 1163. In October 1171 he crossed over to Ireland, the eastern half of which he was able to subject to his direct rule and in the western half of which he was recognized as overlord.

Heinrich also pursued an aggressive expansion policy on the mainland. His main opponent there was the Count of Toulouse , to whose county Henry's wife had a claim that had been made in her family for generations. In 1159 Heinrich started the largest military project of his rule to enforce this claim by force. Here, however, he collided for the first time with the laws of the French feudal structure. Count Raimund V of Toulouse turned for help to King Louis VII of France, who went to the besieged Toulouse and identified himself to Henry, who then had to give up the siege. Even though Heinrich was militarily able to take the city, there was no question of endangering his liege lord. Such disregard for a relationship based on trust and loyalty would not only have broken it, it would also have set a precedent for Heinrich's own vassals to break their bond with him. A reconciliation with the Count of Toulouse took place in Limoges in 1173 , who paid homage to the Plantagenets there and from then on held his county as a fiefdom of Aquitaine.

The relationship between the Plantagenets and their vassals was not free of tension even under Henry II. Especially in those parts of the empire where the feudal nobility traditionally held a strong position vis-à-vis the feudal lord, there were repeated revolts against him by the local nobility. He met strong opposition in Brittany and Aquitaine. The Aquitan nobility, at its head the Lusignans , vehemently resisted Heinrich's attempts to strengthen the ducal power. This resistance, but also Heinrich's ecclesiastical conflict with Thomas Becket , was tacitly promoted by the French king, who hoped that this would weaken the Plantagenet. In order to take into account the different conditions in his lands and to relax the relationship with King Ludwig VII, Heinrich decided to formally divide his power.

To this end, he met with his sons on January 6, 1169 in Montmirail for a personal encounter with the French king. There Heinrich put his eldest son, Heinrich the Younger , in Anjou, Normandy and Brittany and the second oldest, Richard , in Aquitaine. All three then paid homage to the French king, Henry for the entire property and his sons for the areas assigned to them. A year later, Brittany was to be taken over by the third son, Gottfried , who had to pay homage to his older brother Heinrich the Younger, since Brittany was a feudum of Normandy. The youngest son, Johann , was not assigned any land in the Montmirail Agreement (hence "Nohneland"), he was only appointed Lord of Ireland ( Dominus Hiberniae ) in 1177 . In Montmirail, a marriage between Princess Margaret of France and Henry the Younger was agreed, who was also crowned (co) King of England the following year.

Despite the division of power, Heinrich did not think of letting his sons participate in actual power and continued to determine the politics of his family alone. This encouraged the displeasure of the sons, who, driven by their mother and supported by King Louis VII of France and King William I of Scotland, raised themselves against their father in 1183. However, through the use of mercenary companies ( Brabanzonen ) he was able to put down the rebellion both on the British Isles and on the mainland until September 1184. He took Queen-Duchess Eleanor prisoner and his sons again submitted to his authority. In order to reconcile with the French king, an additional marriage between Richard and Princess Alice (Alix) of France was negotiated in 1174 . This should also be a solution in the long-lasting conflict over the property rights of the Norman Vexin with its strategically important fortress Gisors . The Vexin had been in the hands of the Dukes of Normandy for a long time and had been with the Plantagenets since 1144, which the French crown had never recognized. In order to defuse this conflict, the Vexin should be used as a dowry for Alice, through whose marriage to Richard the possession status of the Vexin should be legitimized. However, Richard persistently avoided the marriage bond with Alice in the following years and thus provided another cause of conflict with the French royal family.

In 1180 King Louis VII of France died and he was succeeded by King Philip II , with whom the antagonism between Capetians and Plantagenets entered a new phase. Henry II Short Coat was initially able to act as the protector of the young king, who was in a mutual conflict with his mother, the Count of Blois-Champagne and the Count of Flanders over the reign. After Philip II had prevailed against his opponents, he immediately took the next opportunity to deal with his former protector. The reason for this was the Alice-Vexin conflict, and another argument among the Plantagenets played into his hands. Henry the Younger urged his father to share in power. In order to avoid another violent dispute, Heinrich II. Kurzmantel urged his younger sons in Le Mans in spring 1183 to pay homage to their older brother. Richard, however, who had practically alone ruled in Aquitaine since his mother's captivity, refused. In the fratricidal conflict that broke out, the younger Heinrich was supported by King Philip II with mercenaries and money, while Richard received support from his father. Richard's opponents were joined by his own vassals in Aquitaine, who have been a constant source of unrest for him since his reign. However, the fight ended after the younger Heinrich died unexpectedly in June 1183. The conflict was then ended when Heinrich II. Kurzmantel paid homage to King Philip II in Gisors on December 6, 1183 for all continental areas. Another success came for Philip II in Brittany after Gottfried moved to his court in 1184 and probably paid homage to him for his duchy. This territory was effectively lost to the Plantagenets, as Gottfried's wife resolutely opposed her husband's family after his death in 1186.

The subsequent question of the successor to the Plantagenets' seed heritage immediately led to a new dispute in this family. King Henry II favored his youngest son Johann, to whom he transferred Normandy and whom he wanted to marry off to Princess Alice (Alix). This factual disinheritance of Richard led him in 1187 into an alliance of convenience with Philip II against his father. Philip II was able to achieve significant military successes in the lower Berry, where he was able to take Issoudun in May 1187 and Châteauroux on August 11, 1188 . On November 18, 1188 Richard paid homage to the French king in Bonsmoulins, in addition to Aquitaine, also for Anjou and Normandy, which did not even belong to him, but which sealed the final break with his father. He appeared in 1189 with an army in France to take up the fight, but was quickly defeated by his enemies and fled to Chinon before his son . On July 4, 1189, Henry II. Kurzmantel had to surrender in the Treaty of Azay-le-Rideau and recognize all the conquests of Richard and Philip II. Two days later he died in Chinon.

Richard the Lionheart against Philip II August

With the death of old Heinrich, the alliance of the now English king and sole ruler of the Angevin empire, Richard and Philip II of France, fell apart. Although Richard paid homage to the French king for all land possessions on July 22, 1189 in Chaumont-en-Vexin , he continued to refuse the urgently required marriage to Alice, so the dispute over the Vexin remained topical. A deeper rift initially did not materialize, since both kings had committed to carrying out a crusade to recapture Jerusalem . For the time of his absence Richard entrusted the reign of the empire to his close followers. In England these were the chief justiciars Wilhelm von Longchamp and Hubert Walter , Archbishop of Canterbury .

In the course of the Third Crusade , which both kings began in 1190, a break occurred between them after Richard had married Berengaria of Navarre in Cyprus and thus completed the repudiation of Princess Alice. For the French king, this rejection of his vassal represented a considerable loss of reputation, especially since Richard also ignored the demand for the restitution of Vexins to Philip II. The King of France ended his crusade in July 1191 and returned home, while Richard remained in the Holy Land to fight Saladin . During this time Philip II forced the fight against Richard and found an ally in his brother Johann.

Prince Johann pursued his own interests during the absence of his brother after he had to fear a possible successor in the Angevin Empire. During Richard's crossing to the Holy Land, he had concluded an agreement with the local King Tankred of Lecce in Sicily , which was against the Italian policy of Emperor Henry VI. was directed. In this agreement Richard promised the marriage between his nephew Arthur of Brittany and a daughter of King Tankred. Richard had thus designated the nephew as his successor in the event of his own childlessness, which questioned Johann's prospects for the successor. Subsequently, with the help of Philip II, Johann opposed the rulers appointed by Richard in England, which led to conditions similar to civil war. At the same time, Philip II carried out campaigns in Auvergne and Upper Normandy, where he was able to conquer several castles.

Richard's behavior on the crusade had also favored Philip II's diplomatic position in this conflict, which was increasingly taking on European dimensions. By the Sicilian Agreement Richard won Philip II the emperor as a natural ally and by insulting the Duke of Austria he became an enemy of Richard. On the return journey home, Richard was captured by the Duke in Austria in December 1192 and handed over to the Emperor. Philip II used the capture of his rival in the spring of 1193 to attack Normandy, where he was able to take castles such as Pacy , Ivry and, above all, the long-sought Gisors. In a peace agreement authorized by Richard (Mantes, July 9, 1193), Philip II got all conquests confirmed. Despite Richard's imprisonment, Philip II was only able to take action against him indirectly, as he got into a conflict with the Pope due to his own family problems. Instead, Philip II promoted Prince John in his ambitions, who in return for renouncing Upper Normandy and Touraine, as well as in the event of a successful takeover of the English throne, was ready to take England by fief in favor of France. Philip II also welcomed the notoriously rebellious barons in Aquitaine, who also used the imprisonment of their liege lord for a renewed uprising against him. In the meantime Richard was able to improve his position vis-à-vis the emperor by mediating in Germany in the conflict between the Staufers and Welfen and by paying homage to the emperor for the English regnum. The quick payment of the ransom resulted in his release in early 1194.

Richard first moved to England, where he quickly restored public order, but as early as May 1194 he crossed over to Normandy to force his brother Johann into submission, who from then on remained loyal to Richard. He left England, which Richard was never to re-enter, under the administration of his confidants, whose primary task was to obtain the financial resources he needed to finance his war on the mainland. England, along with Normandy, was the best organized part of the Angevin Empire. Above all, Richard's father had set up an administrative and tax system there that was unsurpassed in terms of efficiency in the West of its time. And yet England only took on the role of a minor province in Richard's perception, whose almost inexhaustible cash reserves bore the brunt of the financial burden for the crusade, the ransom to the emperor and intensive castle building in Normandy ( Château Gaillard ). This financial policy led to widespread rejection among the barons and the urban population for the first time in the final phase of Richard's rule in England. At a council in Oxford (December 7, 1197) at which Richard's governors demanded new tax permits from both the nobility and the clergy, the Bishop of Lincoln , Hugh of Avalon , publicly criticized the king's demands for money. The bishop pointed out that the clergy and nobility of England were obliged to defend the kingdom, but not to participate in the dynastic conflicts of its king on the mainland. Despite this obvious lack of Angevin empire consciousness, Richard continued his war. He no longer cared about English matters, which resulted in the defection of the Welsh under Lord Rhys .

In France, Richard was able to quickly gain the upper hand over Philip after he had defeated him at Fréteval in July 1194 and was able to take several castles from him. In doing so, he forced Philip to make a peace in Louviers on January 15, 1196 , in which Richard also accepted his own territorial losses to Philip for the first time. Thereupon Richard tried in April 1196 to regain control of Brittany, but this prevented his sister-in-law Konstanze by sending her son and Richard's designated heir, Arthur, to the court in Paris. In order to relieve himself of his primary fight against Philip, Richard also sought a compromise with Count Raimund VI. from Toulouse on, who, despite his fief, had always rebelled against the Plantagenets. In an agreement Richard recognized the count in his possessions and married him to his sister Johanna, who was endowed with the agenais as a dowry. In June 1196, King Philip II resumed the war and captured the strong Norman castle of Aumale . Richard countered this offensive with an alliance with the Count of Flanders in order to impose a two-front war on Philip. His diplomatic activities he extended to Germany, where he after the death of Emperor Heinrich VI. supported the choice of his nephew Otto von Braunschweig . In September 1198 Richard was again able to personally defeat his rival Philip in the battle of Gisors . With papal mediation, both parties resumed peace talks in which, among other things, the marriage of the heir to the French throne to a niece of Richard's was agreed. Before Richard could ratify this new peace, he died unexpectedly in April 1199 on a campaign against a rebel vassal in Aquitaine.

Collapse under Johann Ohneland

Aided by the help of his mother, who had paid homage to Philip II for Aquitaine in July 1199, Johann was recognized relatively quickly in all parts of the Angevin Empire, although there were uncertainties among the vassals regarding Arthur's inheritance rights due to different customs in inheritance law came from Brittany. Philip II of France used Richard's death and the lack of a peace agreement to immediately start the war against his former ally Johann. He achieved major conquests in Normandy, where the Counts of Évreux and Meulan submitted to him. Johann himself avoided the fight and moved to England where he wanted to celebrate his coronation. This gave Philipp a much better basis for negotiations than he still had with Richard. On May 22nd, 1200 Johann accepted in the Treaty of Le Goulet considerable territorial losses in Normandy and Berry in favor of Philip, but received in return from him recognition in all other continental possessions.

The subsequent misconduct of Johann provided the French king with a new pretext to take military and legal action against Johann. In August 1200 he kidnapped and married Isabella von Angoulême, the daughter of one of his Aquitanian vassals. The bride had previously been engaged to a member of the Lusignan family, who in turn appealed to King Philip II in this matter, who then initiated a feudal trial against John. After Johann failed to comply with several requests to appear before the court, a default judgment was imposed on him in 1202 by declaring all of his fiefs in France forfeit. To enforce the judgment, Philip resorted to Prince Arthur of Bretagne, who paid homage to the French king for all Angevin possessions in France. Despite a victory over Arthur at Mirebeau in July 1202, Johann could no longer stop the collapse of the Angevin Empire. After the rumor of the murder of the captured Prince Arthur by John had spread in France since the spring of 1203, the vassals in virtually all Angevin territories fell away from him and placed themselves under the direct rule of the King of France. As a result, he was able to bring the entire area north of the Loire, i.e. Normandy, Anjou, Maine and Touraine, under his rule by the year 1204. In Aquitaine and Gascony too, plantation rule collapsed in the same year after the Queen-Duchess Eleanor had died. Although Johann was there as a duke in the legal succession of his mother, he showed little interest in these areas and left his vassals there largely to themselves, only in the Poitou and the Saintonge was his nominal rule maintained by appointed seneschals. Gascony was briefly occupied in 1206 by King Alfonso VIII of Castile , who regarded the land as the dowry of his wife, a sister of John. In an agreement concluded in the same year, Alfonso VIII lifted the occupation again. The feudal relationship with Toulouse, however, was effectively ended.

Johann's real estate was mainly limited to the English kingdom, whose interests he consequently tried to take care of more than his brother. In addition to expanding the royal administration, he asserted the authority of the crown towards the periphery of the country. In August 1209 he renewed the English supremacy over the Scottish king at Norham, which has in fact no longer been exercised since Richard's reign. In Ireland in 1210 John subjugated with extreme severity those Norman lords who, in Richard's absence, had become independent princes. He then pursued the consolidation of his rule through the establishment of a royal central administration based on the English model and through a systematic urban policy (e.g. Dublin , Cork ). Similarly, Johann approached the submission of the Welsh princes, which he forced in several campaigns until 1211 to recognize his suzerainty. By building a castle system, he additionally secured his rule in Wales.

Despite these successes, Johann came under increasing pressure from his English barons in the following years. He gave the occasion for this himself through an aggressive church policy, which brought him excommunication, and through the continuation of his brother's tax policy, which served him primarily to recapture the family mainland areas. To this end, he committed himself to his nephew Emperor Otto IV in the German throne contest against the Hohenstaufen in order to win him over as an ally against the King of France. In addition, Johann pursued an intensive alliance policy in the Flemish-Dutch area against France, which is important for the English export economy. In return, these activities led to France taking sides with the young Sicilian King Frederick II of Hohenstaufen as a candidate against the Welf Emperor. In 1213 John was able to counter an invasion of France in England by submitting in good time to the Pope, whom he recognized as a liege lord of England and was therefore released from the ban. The Anglo-Welf alliance then decided to launch a major offensive against France in the following year, after the position of Emperor Otto in the empire was increasingly called into question by the arrival of Frederick. In the spring of 1214 Johann landed with an army in the Poitou and advanced into the Anjou in order to recapture the ancestral land of his family, while at the same time Emperor Otto advanced with an army in Flanders. On July 2nd, Johann at Roche-aux-Moines was surprised by the French Crown Prince Louis VIII the Lion and put to flight in a short fight. A few weeks later on July 27th, King Philip II was able to achieve the decisive victory over the emperor in the battle of Bouvines .

With the defeat at Bouvines, Johann lost the last chance to restore his family's empire. In England, too, his rule was now endangered, as the barons rose against him. In the Magna Carta (June 12, 1215) he had to grant them far-reaching legal concessions and a share in power. The attempt to counteract this development led to the defection of his barons in 1216, who offered the French crown prince the English crown. Prince Ludwig was able to move into London in May 1216 and bring large parts of England under his control. Only the death of John on October 26th in Newark saved the Plantagenets the throne after his son Henry III. was immediately crowned king and recognized by the Pope. Subsequent military successes of the followers of Henry III. at Lincoln and Sandwich resulted in a departure of the prince in September 1216.

The Treaty of Paris 1259

After Louis VIII had ascended the French throne, he led a campaign in the Poitou in 1224, where the last supporters of the Plantagenet surrendered to him. Only Gascony could be held by Prince Richard of Cornwall . The feudal nobility of Aquitaine entered into a direct loyalty relationship to the French crown in the following years, with which the Aquitaine duchy was effectively dissolved. King Henry III of England was not ready to accept the loss. After former Angevin territories were given to princes of the French royal family as appanages , he decided in 1242 to launch an offensive against the young King Louis IX. the saints . But just a few days after landing on the coast of Saintonge , he was defeated on July 21 at the Battle of Taillebourg , whereupon he had to retreat to England.

Although Heinrich III. did not want to forego his claims, the battle for the Angevin Empire came to an end with the defeat at Taillebourg. The next few years were marked by several armistices between England and France. Heinrich III got similar to his father. with the English barons in a power struggle, which also had its commitment on the mainland as a cause that the barons were no longer willing to support. Finally, Heinrich III saw himself. forced to a lasting peace with France. After the active mediation of his wife, whose sister with Ludwig IX. was married by France, the Treaty of Paris was signed on May 28, 1258 , which ended the nearly one hundred years of war between the Plantagenets and the French crown. Henry III. acknowledged the previous losses of the Plantagenets to the Crown of France, was in return confirmed in the possession of Gascogne ( Guyenne ) and received other areas with the Saintonge and parts of the Angoumois and Périgords returned. The treaty was then ratified by the English barons and entered on December 5, 1259 in Paris with the homage of Henry III., For his French possessions, to Louis IX. in force.

heritage

The era of the Angevin Empire marked the climax in the history of French feudalism, which began with the collapse of Carolingian rule in the 10th century. Neither before nor after the Plantagenets could a family hold such a prominent position of power in France that even overshadowed royalty. Nevertheless, the Angevin Empire played a decisive role in the further development of the Capetian kingdom. Despite their weakness, the Capetians were able to maintain their position at the top of the feudal pyramid and thus at any time prosecute their vassals and thus also the Plantagenets. In their efforts to overcome the Plantagenets, they tackled the development of a complex ideology of domination tailored to their dynasty, which was to contribute to the formation of a feeling of togetherness in the regions of the entire French regnum, including the Angevin territories. King Philip II (also called Augustus since the Battle of Bouvines ) was the first Capetian to call himself rex Franciae (King of France) and no longer rex Francorum (King of the Franks). With the return to the universal concept of power by Charlemagne at the same time , the Capetians created an additional legitimation for undivided rule over the French kingdom.

These developments passed the rulers of the Angevin Empire, namely Heinrich II. Plantagenet and Richard the Lionheart, almost without a trace. Although Richard in particular tried to increase his English kingship through an ideal connection to the mythical British king Arthur ( Excalibur , Arthur's tomb in Glastonbury ) and to legitimize the English supremacy on the islands through the connection with the idea of a Britannica , these measures were also limited on England and its British neighbors. With regard to the mainland, both kings failed to remedy the structural deficits of their country complex through institutional reforms such as the creation of a uniform administrative apparatus and legal system. Likewise, they did not succeed in achieving a feeling of unity among their subjects here. The maintenance of their rule was based solely on military strength, with which they could overthrow opponents, counter attacks from outside and assert dynastic interests against their subjects. This rulership often gave their vassals the appearance of an "Angevin despotism" and thus encouraged their rapid fall to the French king in the first years of John's reign. Ultimately, the Plantagenets could only maintain their rule in England, where they could only ensure their survival by sharing power after the violent rebellion of their barons.

Therein lies the importance of the Angevin Empire for the history of England. While England was culturally and politically strongly influenced by the French mainland through the establishment of a Franco-Norman nobility since the conquest by the Norman Duke Wilhelm in 1066, the island empire took its own historical course under the first Plantagenet kings. The growing opposition of the barons of the kingdom, caused by an unscrupulous exploitation of its financial resources for dynastic interests on the mainland, led to the development of a political self-confidence of the baronial class. The political concessions wrested from the king in the Magna Carta set a decisive course in the constitutional history of England. Last but not least, the collapse of the Angevin Empire favored the development of an English national identity.

Through the possession of the Guyenne, the Plantagenets continued to remain in vassalage to France, although in the further course of history they appeared primarily as sovereign kings of England. The resolution of this Lehnsverhältnisses and the dispute over the power to dispose of the Agenais, which was united after the extinction of the counts of Toulouse and the French royal domain, laid the grounds for further conflicts between England and France, the definitive cause of the outbreak of the Hundred Years War in 14th century contributed.

literature

- Martin Aurell: L'Empire des Plantagenêt. 1154-1224 (= Collection Tempus. 81). Editions Perrin, Paris 2004, ISBN 2-262-02282-8 .

- Dieter Berg : The Anjou Plantagenets. The English kings in Europe in the Middle Ages. (1100–1400) (= Kohlhammer-Urban pocket books. Vol. 577). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-17-014488-X .

- Dieter Berg: Richard the Lionheart. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-534-14511-9 .

- Jean Favier : Les Plantagenêts. Origine et destin d'un empire. XIe - XIVe siècles. Éditions Fayard, Paris 2004, ISBN 2-213-62136-5 .