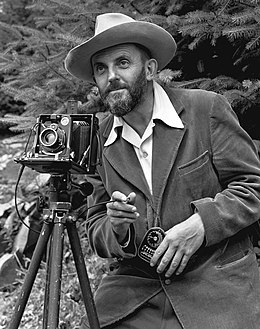

Ansel Adams

Ansel Easton Adams (born February 20, 1902 in San Francisco , California , † April 22, 1984 in Carmel-by-the-Sea , California) was an American photographer , author and teacher of fine art photography . He was best known for his impressive landscape and nature photographs from the national parks , national monuments and the wilderness areas in the western United States, for the preservation of which he actively campaigned throughout his life.

As a co-founder of the f / 64 group, he is one of the pioneers of straight photography and is one of the most important American photographers. Adams wrote numerous textbooks on the theory and practice of photographic technology . The zone system he formulated at the same time as Fred Archer became groundbreaking for artistic black and white photography .

Life

Childhood and early years

Ansel Easton Adams was the only child of Charles Hitchcock Adams and Olive Bray Adams, a family of merchants from San Francisco. The boy was named after Uncle Ansel Easton. The Adams family was from New England on his father's side . The family had immigrated from Northern Ireland in the early 18th century . The grandfather had built up a prosperous timber trading company in San Francisco, which was managed in the successor to Adams' father Charles. The mother's family was from Baltimore and the maternal grandfather had settled in Carson City , Nevada , as a haulier and property speculator.

Adams' parents were politically liberal , otherwise more conservative-bourgeois people. The father was an avid hobby astronomer who was interested in optical equipment in general and photography in particular and had a "Brownie Bullseye" box camera from Kodak as his most modern achievement ; the mother was artistically ambitious and preferred to devote herself to porcelain painting .

Ansel Adams' first childhood memory was the devastating San Francisco earthquake of 1906 , in which the four-year-old smashed his nasal bone as a result of a fall, which was never straightened, and Adams brought in his distinctive crooked, left-pointing nose. Since the Adams' lived in a self-built house in the dunes outside of San Francisco, they were otherwise largely spared the effects of the quake.

The Panic of 1907 , Recessions

In 1907 Ansel's grandfather William James Adams died. With his death and the first major stock market crash in the USA, known as The Panic of 1907 , his company went down. The creeping recession of the following decades took up the entire family fortune of the Adams' family, and Ansel's father tried to salvage the little remaining corporate capital. Secret agreements and share sales by Ansel's uncle Ansel Easton are said to have ultimately led to another financial disaster. Ultimately, the bank took over the property and the once flourishing company was broken up.

As a child, Ansel was often sickly, suffered from colds and various teething problems. Nevertheless, he let off steam on hour-long climbing tours on the steep cliffs on the nearby Pacific coast of Fort Scott or China Beach. The inquisitive boy collected insects and botanized plants. He was also enthusiastic about sports, but was always too impatient to concentrate on one sport. In 1912 Ansel fell ill with measles and had to spend two weeks in bed in a darkened room. To pass the time, his father explained his boxing camera and the age-old principle of the camera obscura that was behind it, and thus aroused the boy's interest in photography for the first time.

Ansel spent most of his elementary school at Rochambeau School in San Francisco. However, because he was considered a difficult child who was mostly bored in class and often involved in fights, he had to change schools several times. After a violent fit of anger, he was finally expelled from school and received home tuition from his father, who taught him basic French and algebra. Charles Adams also made sure that his son read English literature classics and received lessons in ancient Greek from a pastor friend of his. As Adams described in his memoirs, during the numerous conversations with the clergyman he quickly realized that with the help of the intellect he had to create his own critical view of the world, which, as he said, was directed "against intolerance, ignorance and arrogance" . Around this time, the boy also showed a musical talent, and from 1914 he also received piano lessons.

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition , Turning to Music

(photography by Charles C. Moore)

In 1915 his father gave him an annual ticket for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition , the world exhibition held to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal . The gigantic exhibition left a lasting impression on the boy, and above all he was enthusiastic about the concerts that were played on an imposing organ in the exhibition's festival hall, a huge dome. If possible, he never missed any of the concerts. He also often visited the painting and sculpture exhibition in the Palace of Fine Arts, where works by Pierre Bonnard , Paul Cézanne , Paul Gauguin , Claude Monet , Camille Pissarro and Vincent van Gogh were shown.

While looking for a regular school leaving certificate, Ansel attended a few more schools in the following years, and with the eighth grade certificate he formally ended his school career.

From the age of 13, the boy received intensive piano lessons from an elderly lady named Marie Butler, a graduate of the New England Conservatory with many years of teaching experience. She possessed virtuosity in playing and a profound knowledge of music theory and music history ; she knew how to wrest a certain amount of discipline from the boy with a lot of patience and perseverance and to awaken his fascination for the instrument. In 1918 she recommended the young Adams to study music with the composer Frederick Zech (1858–1926). Adams soon developed the desire to become a professional musician.

The Sierra, Yosemite and Photography

Ansel Adams had first been on a vacation trip to Yosemite National Park with his parents in 1916 . While on vacation, his father gave him a Kodak Brownie box camera , Ansel's first camera of his own. The 14-year-old began passionately to capture everything that came before his lens. The boy was so enthusiastic about the vacation that he also spent the summer months in the nature reserve in the following years. In 1919 Adams joined the Sierra Club founded by John Muir . In 1922, Adams published his first article for the Sierra Club Bulletin . In 1934 he was finally to become a member of the board of directors of the club (until 1971).

When the club went to Yosemite in the summer of 1923, Adams met his childhood friend, the violinist and later photographer Cedric Wright (1907–1950) again. During a multi-day excursion through the park, the friendship of the two nature lovers was strengthened, and people exchanged views on music and the mutual interest in photography. Wright dealt with pictorialism and preferred to create portraits that were similar in their technical quality to the early works of Edward Weston . Wright made Adams known, among other things, with the artistically printed books of Elbert Hubbard , the founder of the Roycroft movement.

The friendship with Wright, the relationship with the Sierra Club and the countless excursions in Yosemite Park should arouse a deep lifelong fascination with the wilderness and its protection in Adams. In later years, Adams recalled this time as "the most memorable experience of his life" and emphasized how the intense experience of nature, childhood at the seaside and the early years in the Sierra Nevada had shaped his entire life.

Over time, Adams began to view the snapshots he took on his field trips to Yosemite as a "visual diary," and the more he photographed, the more interested he became in the photographic process behind it. After all, he wanted to learn how to put the pictures on paper himself. Around 1917 a neighbor who ran a photo lab offered him a job as a laboratory assistant. Within a short time, Adams learned the routine of film development. Eventually, he perfected his hobby, and he managed to create expressive images.

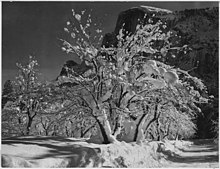

Monolith, The Face of Half Dome

Until the mid-1920s, Ansel Adams saw himself at best as an ambitious amateur photographer. Adams dated a spring day, April 17, 1927, at Yosemite that, he said, "would change his understanding of the medium of photography." It was on that day that Adams broke up with friends Cedric Wright, Arnold Williams, Charlie Michael, and his future wife Virginia Best for a hike to the Diving Board , a rocky outcrop with an imposing view of Half Dome . Adams was carrying 40-pound camera equipment with him in his rucksack, consisting of a corona studio camera, several lenses, filters, six plate holders with twelve glass plates, and a wooden tripod. During the ascent, Adams took several shots, some of which were unsuccessful, a glass plate was accidentally exposed because Adams forgot to protect the camera lens from direct sunlight. After all, he had only two plates left to expose them, as he said, "with the greatest sight the Sierra offers - the Face of Half Dome itself." Adams brought back one of his most famous pictures from this excursion: Monolith, The Face of Half Dome .

In 1937, a fire broke out in Adams' photo lab, and thousands of his original negatives were destroyed or damaged. It took him and his helpers several days to water and dry the rescued negatives. Some photographs, for example Monolith, The Face of Half Dome , which were only damaged at the edge, have enlargements before and after the fire, with the newer enlargements necessarily showing a smaller section of the image so that the damaged areas are not visible. Adams kept the original negatives in a safe for later years.

Albert Bender, Robinson Jeffers

In the spring of 1926 Cedric Wright introduced his friend Ansel to the art collector and patron Albert Maurice Bender (1866–1941). Born in Ireland, Bender had made his fortune as an insurance broker and was considered a philanthropist who had a large circle of friends and had quite influential relationships with important gallery owners, artists and publishers on the west coast. He was particularly interested in the art of printing and rare artist books . He became interested in Adams' photographic work and decided without further ado to create a portfolio with the young photographer . Bender took care of publishing and sales. Adams imagined the portfolio should simply be titled Photographs , but the publisher Jean Chambers Moore had reservations about the word, and so it was agreed that the title was made up of “Parmelian Prints” , but Adams was not very happy with it. When Adams finally held the finished print in his hands, his disappointment was all the greater because the incorrect subline “… of the High Sierras” had been added to the title : because “Sierra” is already a plural. Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras was published in 1927 with an edition of 100 portfolios plus 10 artist copies of 18 photographs each for a retail price of 50 US dollars each.

Ansel Adams and Albert Bender became close friends and together they went on numerous long country trips by car. Through Bender, Adams soon became acquainted with numerous creative people in the Bay Area , including the journalist and poet Ina Coolbrith and the reclusive poet and natural philosopher Robinson Jeffers who was critical of humanism and who predicted a future in symbolic poems nature would get along very well without humans, which came very close to a certain basic mood of Adams. Jeffers' increasingly anti-humanist radicalism and his heightened contempt for human civilization would bring him frequent criticism in later years.

Marriage to Virginia Best

On January 2, 1928, Ansel Adams married his childhood sweetheart Virginia Rose Best in Yosemite. Virginia was the daughter of Harry Best, born in 1904, a local landscape painter who sold paintings, wood carvings and souvenirs in his own studio and shop in Yosemite Park. Ansel had already met Virginia in Harry Best's studio in 1921. Both had a passion for Yosemite and music: Virginia originally wanted to be a singer. Virginia Best and Ansel Adams had been in a changeable relationship for over six years. Their son Michael was born in 1932, and their daughter Anne followed two years later. When Virginia's father Harry Best died unexpectedly in 1936, she took over his shop atelier in Yosemite.

In the early years of his marriage, Adams still wavered between two professions: a career as a concert pianist and that of a professional photographer. By the beginning of the 1930s at the latest, with the onset of the Great Depression , Adams was unable to continue the balancing act financially or emotionally. In order to clarify his further career, he made several trips to New Mexico during this time .

New Mexico, Taos Pueblo

Adams had already taken a trip with Albert Bender to Santa Fe in New Mexico in 1927 . It was Adam's first acquaintance with the barren desert region in the southwestern United States . He was very impressed by the peculiar light of New Mexico, the sometimes bizarre landscape and the huge cloud formations. In Santa Fe they met the poet Witter Bynner and the writer Mary Hunter Austin , who was particularly committed to the concerns of Indians and women. Few photos were taken during Adams' first trip to New Mexico in 1927. In the two years that followed, the photographer took a corona studio camera with him and exposed orthochromatic films.

In 1929, Ansel Adams and Virginia made a long visit to Santa Fe, accompanied by the Irish author and theosophist Ella Young , an acquaintance of Albert Bender. It was at this point in time that Adams began to speculate seriously with earning a living exclusively with photography and possibly settling in northern New Mexico. Ansel and Virginia had accepted an invitation from Mary Austin to stay with her. They quickly became friends and the idea of writing a book on a New Mexico topic soon arose. In consultation with Albert Bender, Adams and Austin agreed on Taos Pueblo as a sponsor and contacted the art patron Mabel Dodge Luhan , who had founded her artist colony Los Gallos in the nearby Taos . The wealthy Luhan had already run influential salons in Europe and New York, in which the intellectuals and creative people of her time gathered. Her husband Tony, himself a Pueblo Indian, made contact with the chief and council of elders of the pueblo . Taos Pueblo was published in 1930 in a first edition of 100 books.

Paul Strand, beginnings as a professional photographer

When Adams visited Mabel Dodge Luhan's one more time in Los Gallos, he made the acquaintance of photographer Paul Strand and his wife Becky as well as the painter and photographer Georgia O'Keeffe , the writer DH Lawrence and the architect and painter John Marin , all of whom were guests of the art patron. Paul Strand was very interested in Adams' Taos book, and so the two photographers started talking. Strand showed Adams his work, which at that time he only had to hand as 4 × 5 inch large format negatives in a cardboard box. Despite the lack of positive prints, Adams was fascinated by Strand's perfectly composed pictures:

“They were negatives full of glowing shadows and strong lights that showed subtle tonal gradations. The compositions were of unusual perfection, the peripheral zones free of disturbances, the picture elements, which he had carefully selected and interpreted as form, wonderfully distributed - everything simple, but of great power [...] "

The meeting with Paul Strand gave Adams the decisive impulse: Suddenly he recognized the creative possibilities that might be in the medium of photography. With the decision to finally give up his career as a musician and to work as a professional photographer in the future, Adams returned to San Francisco. In the years that followed, Adams had a lively pen friendship with Strand.

In 1930 Adams built a house and studio next to his parents' house and began working as a commercial photographer. In the beginning, under the increasing pressure of the economic crisis, he photographed, as he said, “everything: from catalogs to industrial reports, from architecture to portraits.” Although he always preferred artistic photography and his later teaching activities, Adams should Remaining successful as a commissioned photographer into old age and doing photo reports, for example for Fortune or Life magazine, or taking advertising photos for AT&T , Kodak or Nissan , among others . Much of his later commissioned work for paying customers was done in color.

As early as 1929, the Yosemite Park and Curry Company (YPCCO) , which ran the park's concession operations, hired him to take on the public relations work for Yosemite and primarily to take pictures of the winter sports opportunities to attract tourists. For many years, YPCCO Adams was the most important client. His fellow photographer Imogen Cunningham , whom he had met through Albert Bender around this time, in the late 1920s, and with whom he was a lifelong friend, always viewed his commercial work with mixed feelings and sometimes criticized him with humor with the words “Adams, you sold you again. ”Cunningham was initially under the influence of pictorialism, but in the mid-1920s he also turned to straight photography .

From an artistic point of view, Adams did not particularly value the pictorialist photography, which was widespread at the time. The style seemed too mannered to him, and so far he had seen only a few photographs that he found artistic, and his knowledge of the history of photography and photographers had been extremely poor. Adams had begun to experiment at the latest since his meeting with Paul Strand in New Mexico; he tried out new photographic directions and now worked with unstructured, smooth photo papers with a glossy surface, as did his role models Strand and Edward Weston. Eventually he got a finer feel for the light and the tonal gradations in the prints. He noted: "I felt liberated: I was able to create a good negative through the visualization and now reliably convert it as a fine image on glossy paper."

Group f / 64

One evening in 1932 Ansel Adams and the photographers Imogen Cunningham, John Paul Edwards, Sonya Noskowiak , Henry Swift and Edward Weston met at the photographer, filmmaker and Berkeley student Willard Van Dyke to discuss the idea of “ straight photography " , The" pure photography ". Although the work of those involved was sometimes very different, they agreed to pursue a common goal and to define a new way of creative photography that should clearly stand out from traditional pictorialism. At another meeting they discussed a name for the group. The present young photographer Preston Holder, a fellow student of Willard Van Dyke, suggested "US 256", the outdated system name for the very small f-number 64, which meant a large depth of field . But because it was likely to be confused with a US motorway, they agreed on “ f / 64 ” , corresponding to the new name for US256.

“Group f / 64” should become the catchphrase for direct, linear photography as an independent art form and not the imitation of another art form. The members made it their goal to present this as soon as possible in a “visual manifesto” and designed an exhibition. The established gallery owners were initially less than enthusiastic, and the local art scene in San Francisco reacted rather negatively to the idea that photography should be art. Only Lloyd Rollins, the director of the MH de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco, was open-minded and agreed after an appraisal of the photographic work. For Ansel Adams it was the third major exhibition in an art museum. In 1931 he had a solo exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and exhibited at the de Young that same year. The seven founding members of the group f / 64, Adams, Cunningham, Edwards, Noskowiak, Swift, Weston and van Dyke, invited four other photographers who followed a similar concept in their photographs: Preston Holder, Consuela Kanaga, Alma Lavenson and Brett Weston , the son of Edward Weston.

The exhibition ran from November 15 to December 31, 1932. 80 photographs were shown, which were available for purchase: Edward Weston charged fifteen dollars per picture, the other participants ten. During the exhibition, the group distributed a jointly written manifesto. Both the exhibition and the manifesto caused a sensation and led to heated discussions, which, according to Adams, “were largely negative.” Mostly artists and gallery owners filed written complaints against the museum, which dared to show photography as an art form in a public space. Ultimately, the Board of Trustees and Museum Director Rollins sided with the photographers. Leading the criticism were the Pictorialists, above all William Mortensen, a photographer from Los Angeles who was caught up in the painterly tradition and who, in Adams' opinion, disrespected the group f / 64 in specialist magazines. For some time after the exhibition, Adams exchanged controversial letters with Mortensen.

The group f / 64 only did one more exhibition. After Willard Van Dyke, the initiator of the group, moved to New York and the other members also had their own goals, they rarely met; eventually the group broke up informally. In 1933, Adams opened a small gallery in San Francisco, the Ansel Adams Gallery , as the group's “estate administration” , which was under the lasting impression of a visit to Alfred Stieglitz and which was modeled on Stieglitz's galleries in New York. In addition to the pictures from the first Group f / 64 exhibition, Adams also presented paintings, sculptures and prints by various artists with a commercial focus.

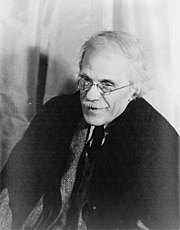

Alfred Goldfinch

In March 1933, Ansel Adams, accompanied by his wife Virginia, undertook an extensive trip to the east coast , which led via Chicago and Detroit, including visits to museums, to Rochester , where Adams visited the Eastman Kodak factory . The destination of the trip was New York City , where the Adams arrived on March 28th. In addition to visits to the theater and museums, Ansel definitely wanted to meet Alfred Stieglitz , the most influential gallery owner and mentor of photography in the United States of the time , with photographs in his luggage, to show him his pictures.

When Adams first met Alfred Stieglitz in his gallery An American Place on Madison Avenue , Adams found the New York photographer cool and unwelcoming, but Stieglitz finally viewed Adams' work with benevolence. With Stieglitz's approval, Adams presented himself to the influential New York gallery owner Alma Reed, who ran Delphic Studios, one of the few renowned art galleries that also showed photographs. In November 1933, a sales exhibition of 50 photographs by Adams opened at Delphic Studios , which although not a financial success during the Great Depression , was accompanied by a surprisingly good review in the New York Times .

From then on, Adams visited Alfred Stieglitz once a year in New York in order to exchange ideas with him and to show new pictures. It was not until January 1936 that Stieglitz agreed to do an exhibition with Adams; the pictures were shown in a successful show at An American Place in November 1936 . Adams wrote to his wife Virginia happily: “The show at Stieglitz is unusual - not only because the pictures are stylishly coordinated and hung. Your relationship to space and the relationship to Goldfinch are things that only happen once in a lifetime. "

The Newhalls and the MoMA

In 1939 Adams met the art historian Beaumont Newhall and his wife Nancy in New York , with whom Adams had been in correspondence since his 1935 book Making a Photograph . Beaumont Newhall was at the time a librarian at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), he had a keen interest in photography as an art form and wrote numerous essays and reviews on the subject. A lifelong friendship grew out of the correspondence. Together with Nancy Newhall, Adams published several books in later years.

In 1940 Adams became curator of a larger picture show in San Francisco, which was to show a cross-section of the history and development of photography under the title A Pageant of Photography as part of the Golden Gate exhibition . The spectrum ranged from the beginnings of photography with Timothy H. O'Sullivan's photographs of the Civil War to Man Ray's rayographs . The accompanying exhibition catalog was extensive and contained essays by Beaumont Newhall, Dorothea Lange , László Moholy-Nagy , Nicholas Ulrich Mayall from the Lick Observatory , Grace Morley from the director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Paul Outerbridge.

Beaumont Newhall and his wife had also come to the West Coast from New York. Adams' photo exhibition at the Palace of Fine Arts inspired the Newhalls to expand MoMA's photographic department. After their return they were able to convince the inaccessible Alfred Stieglitz of this idea. For his part, Adams managed to win over photographer Arnold Genthe for the opening exhibition planned for the MoMA that same year. Both Stieglitz 'and Genthe's contributions were considered indispensable, as both were among the pioneers of artistic photography in the USA.

On December 31, 1940, the first exhibition of the new photographic department at MoMA opened under the title Sixty Photographs . The show was extensive and documented all of creative photography from its beginnings to the present. Works by Berenice Abbott , Ansel Adams, Eugène Atget , Ruth Bernhard , Mathew B. Brady , Henri Cartier-Bresson , Harold E. Edgerton , PH Emerson, Walker Evans , Arnold Genthe, David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson , Dorothea Lange, Henri Le Secq , Helen Levitt , Lisette Model , Moholy-Nagy, Dorothy Norman, TH O'Sullivan, Eliot Porter, Man Ray, Henwar Rodakiewicz, Charles Sheeler , Edward Steichen , Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Luke Swank, Brett Weston , Edward Weston and Clarence White, and unknown press photographers.

Edward Steichen

With the outbreak of World War II , Beaumont Newhall volunteered for air reconnaissance in Europe, and his wife Nancy and Ansel Adams took over the board of trustees for the photo department of MoMA at short notice. Adams served as the vice president of the photography committee. In the course of the war, Edward Steichen , who had been commissioned by the US Navy with the photographic documentation of the Pacific War , took over the management of the MoMA. Since his first meeting with Steichen, Adams had a pronounced antipathy for the photographer, especially since he designed exhibitions of wartime propaganda . In Adams' view, these exceeded the remit of an art museum. Eventually discrepancies arose, as a result of which both the Newhalls and Adams resigned from their posts. Steichen took up the post in 1947 as the new director of the photographic department at MoMA, which he headed until 1962. He was succeeded by John Szarkowski , who was to curate a large traveling exhibition of Adams' work in the 1970s.

In 1954, Adams and Steichen came into contact again when Steichen put together his exhibition The Family of Man (1955) and requested Adams' negatives. Adams sent Steichen the images Mount Williamson , Sierra Nevada and From Manzanar, California as duplicates and requested permission to make the prints. Steichen refused and had Adams' work, as the latter criticized, "enlarged disproportionately". Adams later noted, “When I saw the finished mural, I felt sick. He had demoted Mount Williamson , one of my strongest paintings, to wall paper. [...] I lost interest in MoMA for years. "

Moonrise , Hernandez, New Mexico

In the spring of 1941, Adams received a letter from then US Secretary of the Interior, Harold L. Ickes, requesting that they photograph the national parks in the United States in order to create murals for the Department; around the same time, the US Potash Company in Carlsbad , New Mexico commissioned him to photograph the potash mines near Carlsbad. For this purpose, Adams, accompanied by his eight-year-old son Michael and his long-time friend Cedric Wright, traveled to northern New Mexico to take various landscape shots. Near the village of Hernandez, travelers were faced with an extraordinary sight when the moon suddenly rose over the snow-capped mountain peaks, while in the west the late afternoon sun flashed white crosses in a churchyard. Knowing that such a motif would never be repeated, Adams stopped the car to quickly unload and set up his bulky plate camera. He only succeeded in taking one shot, with the second negative the sun had already disappeared behind a bank of clouds and "the magical moment was over forever," as he recalled. Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico was to become Ansel Adam's most famous photograph. Years later, the photographer received letters asking if it was a double exposure , which he always denied.

Unfortunately, in his excitement, Adams forgot to date the picture, which is why biographers and photographic historians argued for a long time about when the exact date of the legendary photo was taken. Beaumont Newhall succeeded in the 1980s with the help of his friend, astronomer David Elmore, to calculate the date of the rare sun-moon constellation with the help of azimuth tables and maps on a computer, according to which Moonrise should be on October 31, 1941 between 4 p.m. and 4 p.m. : 5 a.m. local time. Recent research, however, dated the creation date to November 1, 1941, 4:49 p.m. MST .

National parks

After Adams photographed the US Potash Company's potash mines , he traveled on to Carlsbad Caverns National Park to begin photography for the US Department of the Interior. During the trip he recorded from the cliff dwellings of the Anasazi in Mesa Verde National Park or from the Adobe - Pueblos of Acoma , also felt Adams in his own way the historical photographs of Timothy H. O'Sullivan after which this already in 1873 in Canyon de Chelly had made.

In the summer of 1942, the photographer continued his extensive photo excursion for the government through various national parks : he photographed the geysers of Yellowstone National Park and stopped in Rocky Mountain National Park in Glacier National Park and finally in Mount McKinley National Park (today Denali National Park ). Much to Adams' displeasure, the mural project was discontinued in July 1942 under pressure from World War II and never resumed after the war.

After the war, Adams competed in the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation for a Fellowship ( scholarship ), so that he could continue his work in the national parks for a book project. Adams received the Guggenheim Fellowship twice: in 1946 and 1948. The fellowship enabled him, among other things, to travel by plane to southern Alaska , where he and a group of geologists took pictures of the ice fields around Glacier Bay in Glacier Bay National Park . From all the national park material, he extracted the portfolio The National Parks and Monuments and the photo book My Camera in the National Parks , published in 1950.

Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park , 1941

Canyon de Chelly , 1941

McDonald Lake, Glacier National Park , 1941

Acoma Pueblo , 1941/42

Old Faithful , 1942

Manzanar, Dorothea Lange

In the summer of 1943, Adams was entrusted with the project by Ralph Merrit, the newly appointed head of the Manzanar Internment Camp, to resolve the predicament of the Nisei , native-born American citizens of Japanese descent who were lonely after the attack on Pearl Harbor as part of a government internment program Areas had been forcibly relocated. Ansel Adams decided to go to Manzanar in late autumn of that year. He already knew the deserted area in Owens Valley from the stories told by Mary Austin and from Dorothea Lange's documentary photographs that she had taken here the year before. The visit to the desolate barracks settlement touched Adams deeply. One of his most famous pictures was taken in Manzanar, Winter Sunrise, The Sierra Nevada, from Lone Pine, California (1943).

The photo report from the Manzanar internment camp, which Adams' only contribution directly related to the war, was published in 1944 as the book Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans . The work received positive reviews and topped the San Francisco Chronicle's bestseller list in the spring of 1945 .

Ansel Adams worked with Dorothea Lange on several stories together in the 1950s. Lange also lived in the Bay Area of San Francisco and in the 1930s had earned a reputation as a social documentary photographer on behalf of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) founded under Roosevelt with her haunting images of American country life . Adams' relationship with Lange was friendly, despite some disagreements, and the two often exchanged lively photographic and political views. Adams saw a certain sympathy for Trotskyism in Lange's work , which the photographer never expressed directly. "She had integrity in her convictions and was full of skepticism about the smug 'good old boy' attitude that she saw predominantly in industry and politics," Adams recalled in his memoirs of the photographer. The two had a lively correspondence for many years.

On behalf of Life magazine , Adams and Lange realized the photo essay Three Mormon Towns in the summer of 1953 about the secluded Mormons in southwest Utah .

Edwin Land and Polaroid

In 1948, Adams met the physicist and photography pioneer Edwin Herbert Land at a party in his home in Cambridge , Massachusetts . Land had just presented its new Polaroid -Land- separating process and invited the curious Adams to his laboratory the following day, where Land took an instant portrait of Adams. It was Adam's first encounter with the Polaroid process. Since Land only counted scientists and theorists at that time, but no creative people with photo- technical knowledge, he hired Adams as a technical consultant. In addition to an instant camera with the accompanying films, Adams was given the task of examining the quality and performance of the material, which ultimately resulted in a lifelong business relationship between Adams and Polaroid, as well as a close friendship between Land and Adams.

From the 1950s onwards, Ansel Adams made numerous photographs on Polaroid material. A well-known shot from 1968, El Capitan, Winter Sunrise , showing the monolith El Capitan in Yosemite, was made on Polaroid Type 55 P / N , a high-resolution positive / negative black and white film .

Teaching activities

In 1940, Ansel Adams took over the photography department at the Art Center School (now the Art Center College of Design ) in Los Angeles at short notice and also led numerous workshops "on site" in Yosemite National Park. In 1946 he was asked by then President of the San Francisco Art Association , Ted Spencer, to set up a photography department at the California School of Fine Arts , now the San Francisco Art Institute . Adams enthusiastically accepted and immediately began planning three darkrooms and a large demonstration and classroom for the university. But the cost of Adams' project far exceeded budget, which aroused displeasure in the other departments. “The painters, sculptors, graphic artists and potters rose like a man in anger. Photography is not art, they claimed, and has no place in an art school ... ”Adams recalled.

With Spencer's support, however, he was able to start teaching and finally convinced his critics of the technical and artistic-aesthetic aspects associated with photography. Adam's photographic department was one of the first to teach the medium of photography in a fine arts institution . But after just one year, when he received the Guggenheim scholarship, Adams gave up his work at the institute due to lack of time. In moral duty he finally found an equal successor in Minor White .

Ansel Adams still held numerous workshops well into old age, in which he lectured on his zone system and other findings in the theory and practice of photography. In this context, numerous textbooks on photo technology were created , such as Camera and Lens and The Negative (both 1948), The Print (1950) or Natural Light Photography (1952) and Artificial Light Photography (1956).

Carmel, The Friends of Photography

After living alternately in San Francisco and Yosemite since the early 1920s, Ansel and Virginia Adams moved to Carmel-by-the-Sea in 1961 , where a friend of the Adams' Dave McGraw had gathered a small colony of artists . The Adams' decision to move to Carmel was primarily a logistical one: Ansel still had business in New Mexico, while Virginia continued to run Best's Studio , her father's former shop in Yosemite. Dick McGraw offered the Adams three acres on Wild Cat Hill in the Carmel Highlands. With a heavy heart, Adams separated from his parents' house in the dunes of San Francisco, where he had temporarily lived since it was built in 1903. Adams' mother Olive had died in 1950, and father Charles followed her just under a year later. With the help of the architect Ted Spencer, Adams had a house designed according to his ideas, the center of which was to form a large darkroom that was accessible from all areas of the house.

In Carmel, Adams founded Friends of Photography in 1967 together with Morley Baer, Beaumont and Nancy Newhall as well as Brett Weston as a non-profit organization that promoted creative photography and organized exhibitions and showrooms. Within a few years the association became an internationally known institution with several thousand members. After Adams' death in 1984, the group moved from Carmel to San Francisco and opened the Ansel Adams Center for Photography at Yerba Buena Gardens in 1989 .

Late years and death

With increasing age, Ansel Adams limited his activities to smaller workshops for the Friends of Photography , to the publication of photo books and articles in specialist journals as well as to the reproduction of his most famous photographs, which had become coveted collector's items. In addition, since the Nixon era, Adams was increasingly concerned with political initiatives to preserve the national parks. In 1975 he submitted a memorandum to the incumbent US President Gerald Ford for this purpose .

In the 1970s, the photographer began to settle his estate and founded two trusts for this purpose : on the one hand the Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust , which was to control all future publications and reproduction rights, and on the other hand the Ansel Adams Family Trust , into which the net proceeds of the Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust , which will benefit only the Adams family, after Ansel and Virginia's death, the children Anne and Michael. Adams also decreed that his photographs should no longer be associated with a commercial product.

In the mid-1970s, Adams did his last commissioned work and publicly announced that he would no longer accept orders for pictures from December 31, 1975. With Adams' announcement, the prices of his photographs at art auctions began to rise steadily. Most of the years 1976, 1977 and 1978 he spent fulfilling outstanding orders. In the last few years of his life, the photographer viewed around 40,000 negatives. While Adam was still alive, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico reached a record auction price of $ 71,000, the highest price ever paid for a photograph.

Although Adams' work was shown in international shows during his lifetime, he did not travel to Europe for the first time until 1974 to visit an exhibition of his work in Arles and to give lectures. He met fellow photographers such as Bill Brandt , Brassaï , Henri Cartier-Bresson and Jacques-Henri Lartigue . In 1976 he repeated his lecture tour to Arles, and in 1979 he visited the Victoria and Albert Museum in London again. In the same year, Adams, who had suffered from increasing heart problems since the early 1970s, underwent an operation in which he was triple bypassed . He turned down a fourth lecture tour to Europe in 1982. In 1979 John Szarkowski , Edward Steichen's successor on the board of trustees of the photographic department of MoMA, organized the major traveling exhibition Ansel Adams and the West , which showed 153 landscapes by the photographer. The exhibition opening coincided with Adams' book release, Yosemite and the Range of Light . The show was a huge success and was recognized by art critic Robert Hughes with a cover story in Time Magazine.

In 1981, Adams was the second after Lennart Nilsson to be honored with the Hasselblad Gold Medal by the Erna and Victor Hasselblad Foundation . The award by King Carl XVI. Gustaf from Sweden took place at MoMA. Adams had already met the Swedish photographer and inventor Victor Hasselblad on a visit to New York in 1950. At the time, Hasselblad asked Adams to try out one of their first cameras, the Hasselblad 1600F medium format camera . From then on, Hasselblad models were one of Adam's cameras of choice.

Ansel Adams' eightieth birthday on February 20, 1982 was celebrated with numerous exhibitions, retrospectives and festivities organized by Friends of Photography . To Adams' particular joy, the Russian pianist Wladimir Aschkenasi , whom he greatly admired, gave a private piano concert in the Adams home in Carmel.

Adams died of heart failure on April 22, 1984 at the age of 82. In his honor, the wilderness area Minarets Wilderness , which surrounds the mountain range The Minarets in the Sierra Nevada , was renamed Ansel Adams Wilderness that same year . His wife Virginia Best Adams passed away on January 29, 2000.

plant

Photo-historical classification

Ansel Adams is considered to be a representative of “ straight photography ” , “pure photography”, which, following the tradition of realism in painting, is committed to strict visual aesthetics and demonstratively opposed to the dogmatics postulated by group f / 64 was supposed to judge the pictorialism popular at the time , which, with its sentimental style, was perceived as tastefully "impure". His works from the early 1930s were still very much under the influence of the group f / 64 and are based on Paul Strand or Edward Weston in the representation of pure forms . Only in the period that followed, from the mid-1930s, did Adams break away from the restrictive theories of group f / 64 and switch from a more two-dimensional design to a more plastic image structure. Although Adams' landscapes and the precision of their implementation were groundbreaking in photo history, photographers of the New Objectivity in German-speaking countries such as Albert Renger-Patzsch found a similarly “pure” visual language.

Photography as an art form, relation to music

In his numerous writings, lectures and workshops, Adams clearly presented his methods of creating and refining a perfectly delineated, "well-composed" photograph and demonstrated the possibilities that pure photography can offer as an artistic medium of expression. Coming from a classical music education, Adams transferred his knowledge of musical composition to composition in art and legitimately declared photography as “belonging to the fine arts”. Adams regarded (and described) the camera with its accessories made up of various lenses and filters as being equivalent to music as an “instrument”.

The “anticipated” fine picture

In contrast to fast-paced reportage photography as well as the emerging snapshot photography , which at the latest since the introduction of the handy Kodak products ( "You press the button - we do the rest" - "You press the button, we do the rest" , was the slogan of the time company) and the small picture formats often led to a mechanical arbitrariness of the sitter, Adams concentrated already on site to a certain "forward unsuspected" ideal composition, which he visualized and the deduction finally in an elaborate darkroom process using tonal corrections the desired form of presentation gave that he himself referred to as an expressive "fine picture". Adams emphasized this “premonition” in relation to his photographer colleague Henri Cartier-Bresson , who is regarded as a snapshot photographer par excellence, but despite this speed, visualized the subconscious composition of the image at the “decisive moment” and thus found its optimal expression.

The zone system

Together with photographer and college lecturer Fred Archer, Ansel Adams developed and formulated the famous zone system towards the end of the 1930s . The process, which Adams subsequently developed, is based on a series of articles in the US Camera magazine . With the help of the zone system, Adams tried to transfer the contrast range of the motif so skillfully to the (usually significantly lower) contrast range of the black and white film that a natural image impression was created. The goal was technically perfect, neatly drawn negatives that could be easily enlarged. But that does not mean that he refuses to be tampered with in the darkroom . The negative was for him only an intermediate step on the way to the already existing finished in his head picture - only this intermediate had to meet the highest standards, so that he could realize his idea right at the end in the finished print. Based on the music, he interpreted the negative as a score, but only the print was the interpretation and the finished work.

Adams' zone system was received ambivalently by photographers and the trade press; some found the method helpful to expand creative possibilities under the aspect of “ calibrated recording”, critics of the zone system and supporters of snapshot photography found the principle too didactic , too cumbersome and not very practical.

The technology

Adams presented his working method in numerous specialist books, in which he often goes into technical aspects such as exposure times , devices used, filters, film materials or the subsequent work in the darkroom or in the photo laboratory , based on the genesis of a selected work .

Adams worked mainly with corona and later Linhof - large format (professional) cameras as well as from the 1950s with Hasselblad - medium format cameras in black and white slide film. Until about the early 1930s, he used the usual orthochromatic films, which is why some pictures taken under blue skies produced relatively bright results without being filtered. In order to make the sky appear dramatically dark, the photographer used color filters (mostly Wratten No. 29 red filters) for panchromatic films . This becomes clear, for example, in Monolith, The Face of Half Dome from 1927.

In his own photo lab, Adams used a purpose-built horizontal magnifier based on an old converted plate camera. The device also enabled him to enlarge his early large format negatives, some of them on 8 × 10 inch glass plates.

Although the trend was towards large format as early as the 1930s, Adams often only made contact prints of his negatives in the format 20 × 25 cm for exhibition purposes , which he presented in white passe-partouts . To contrast increase and retrieve a high archival stability to achieve toned Adams deductions mostly with a direct selenium toning.

Alfred Stieglitz gave Adams the idea of ideally showing the works in front of a neutral wall in a mixed lighting of indirect artificial light and subdued daylight in order to increase the effect - a type of presentation that is common today in the White Cubes .

Adams and color photography

What is less well known is that Adams also took color photographs: during his photographic life he made over 3,000 photographs on color slide film . Most of the photographs were taken in the 1940s and 1950s, partly as test shots for Kodak's newly developed Kodachrome film. When Adams died in 1984, he was already planning a book on color photography . The subject had preoccupied him, albeit with unease, since the 1950s. In the 1980s he admitted that if he could start all over again as a young photographer, he would probably take pictures in color, “actually,” says Adams, “I don't particularly like color photography. That's not my case. "

When asked if he was working in black and white because his color vision might be impaired, he replied that he had had his color vision checked and that it was okay. He prefers black and white because he has more control over the process. A large number of his commercial commissioned works were created in color. Through his acquaintance with Edwin Land , he also had the opportunity to test numerous new instant photo materials with which he achieved impressive image results.

Quotes

"Two people are always involved in a picture: the photographer and the viewer."

"A photo is mostly just looked at - you rarely look into it."

"Twelve good photos in a year are a good result."

reception

Ansel Adams was one of the most important American photographers of the 20th century during his lifetime. His name, which is now inextricably linked with the photographic documentation and the preservation of the national parks and national monuments in the western USA, has become a synonym as well as a label for technically adept, high-quality nature and landscape photography, which was already extensively commercialized during his lifetime has been.

Importance as a conservationist

Adams spent much of his life in the US national parks and Indian reservations , where he not only worked as a photographer, but also supported her with his work, publications and workshops. His numerous writings quickly aroused public interest in the hitherto unknown wilderness areas of the West.

Adams' work Sierra Nevada: The John Muir Trail , first published in 1939 , had a significant influence on the then Interior Minister Harold Ickes and fitted into the regionalist aspect of the state program of "economic renewal" under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, which included 1940 Established Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks . In 1968, Adams was recognized by the National Park Service (NPS) for his services with the Conservation Service Award , the highest civilian honor awarded by an agency of the US Department of the Interior.

For the Sierra Club , of which Adams was a board member from 1934 to 1971, the photographer produced numerous photo reports with accompanying essays, which appeared in the club magazine Sierra Club Bulletin and which were decisive for the tourist development and the economic and political importance of the nature reserves that were still untouched at the beginning of the last century contributed. In the beginning this was done under simple nature conservation aspects , but with the beginning of the Second World War the region began to be developed and popularized, which led to expansive commercialization by the 1960s at the latest, when parts of the natural areas were opened to property speculators and concessions to build power stations were granted. This eventually led to differences, as a result of which Adams resigned as a board member in 1971.

Perception through art criticism

In a new edition of his highly acclaimed work History of Photography (History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present) , the photo historian and curator Beaumont Newhall , a contemporary and friend of Adams, emphasizes the technical quality of Adams' work, which "was in his exhibition as early as 1936 in Stieglitz's gallery An American Place were of a sensitivity and sincere directness rarely encountered. ”Newhall stated:“ Adams has excellently demonstrated in his photography, his writings and his teaching activities the possibilities that pure photography offers as a medium of expression. "And refers to Adams' enthusiasm for experimentation, his technical mastery, and his" spiritual feeling for the pristine regions of the earth, skills with which the photographer created great landscape shots. "

In 1979 the art critic Robert Hughes dedicated a cover story to the photographer in Time Magazine and emphasized that no other living photographer had contributed to determining the difference between documentary and aesthetic, or “emotional” use of photography. The photo historian John Szarkowski - director of the photographic department of MoMA from 1962 to 1991 - characterized Adams on the occasion of the Ansel Adams retrospective curated by him, Adams at 100 , which was shown in 2003 at the MoMA in New York and at the SFMOMA in San Francisco In an interview with the New York Times : “One aim of the exhibition is to free Adams from the image of the green social realist. Although Adams had a lifelong interest in the preservation of the wilderness, his best work came about for reasons that were far more personal and mysterious [...] but he would be indignant if someone assumed that he had felt something close to religious in the traditional sense. In his private letters it becomes clear that his experiences of the natural world were basically mystical experiences and that his only truly lasting artistic problem was to provide physical proof of this experience. "

Compared to socially critical contemporaries, Szarkowski relativized Adams' presumably less importance for social documentary photography in the USA: “Until around 1960, the fact that he was photographing trees and snow-capped mountains was considered by many who believed that photography should document human suffering rather than Felt 'moral wrong'. Only later did he become a hero for something he had never intended when doing his best work. "

In the context of the retrospective, the New York Times described Adams in commercializing his name as “America's most beloved photographer [...] whose photographs of thundering rocks and glittering groves through an endless stream of posters, calendars, books, and screensavers are more popular than ever ... "In a dossier on" New Photography in the United States ", the art historian John Pultz viewed Adams as a photographer with craftsmanship and technical perfection who" in the 1940s and 1950s devoted himself almost exclusively to the representation of majestic landscape panoramas, while in the diversity of his Motive in the 1930s achieved the precision that Strand and Weston had established in the 1920s. "

Significance for the establishment of photography as an art form

In a departure from the short-lived pictorialism associated with painting and thus despised as "weakly sentimental", Adams, in the wake of Edward Weston and the jointly founded group f / 64, introduced a strictly composed visual language into photography, which was precisely and sharply focused Reproduction of "pure forms" of reality. Adams and group f / 64 met with rejection from contemporary artists and critics. A cultural and aesthetic upgrading of the medium of photography as a new and legitimate form of the “fine arts” was generally accepted only hesitantly until the middle of the 20th century, which is why Adams' appointment as university lecturer for photography in 1946 initially met with criticism in the established departments.

In an obituary for the photographer in 1984, Der Spiegel stated that Adams was honored “which placed him alongside the great writers, painters and composers of his generation: the American Ansel Adams had made a significant contribution to establishing photography as an art form in its own right . "

Critical considerations

The art photographer and pictorialist William Mortensen (1897-1965) was one of Adam's harshest critics in the 1930s. After Mortensen's death, Adams allegedly prevented the archiving of his photographic estate at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, and Mortensen was forgotten. The art-historical rehabilitation of William Mortensen: A Revival , recently published by the Center for Creative Photography , suggests an effort by Adams to erase the adversary from the annals of photographic history. In his autobiography, Adams only reproduced the long-standing correspondence with Mortensen on one side.

The author Jonathon Green takes a clearly critical position in his work American Photography: A Critical History 1945 to the Present , which assigns Adams puritanical - technocratic characteristics and describes him as “an archetypal American engineer of the 19th century” who, “like all great master builder of his time, who used his knowledge for the aesthetic and spiritual well-being of mankind ”. Adams' work is of the puritanical grain: strict and conservative with the obsession with technological control, which shows another fundamental American trait, as already seen in Stieglitz and Steichen: the aggressive, acquisitive, inventive engagement with technology and practical use of new technologies.

“The formalism that pervades Adams' work relates directly to his belief in technology . For Adams, technology is redeeming. He could even sell cars or televisions with a clear conscience. In fact, it seems he relies on technology more than sight. Of all the great American photographers, he is the one with the most inconsistent work. If his work is successful, it is breathtaking, but if it fails, it is nothing more than a finger exercise in the zone system - sweet and decorative. "

Adams on the art market - record price for allegedly rediscovered negatives

In 2000, the house painter Rick Norsigian of Fresno, California, bought two boxes of 65 glass plate negatives for US $ 45 showing photographs of Yosemite Park. According to an expert opinion commissioned by Norsigian, the negatives are said to come from Adams. The lettering on the paper sleeves of the negatives is also said to be identical to the handwriting of Adams' wife Virginia and the negatives are from the 1920s and 1930s. Norsigian went public with the find in 2007 via the Los Angeles Times . At a press conference in 2010, art expert and gallery owner David W. Streets stated that it was "a missing link in the story and work of Ansel Adams" and put the value of the find at around $ 200 million (around $ 153 million) , 5 million euros). Ansel Adams' heirs and trustees, however, questioned the authenticity of the find and remarked that if the negatives were actually genuine, they would not have such great value, since only original prints made by Adams himself would be of high collector's value. Later comparisons revealed similarities with the early photographs of an otherwise unknown portrait photographer named Earl Brooks. In March 2011, Norsigian and the Adams Trust reached an out-of-court settlement that denied Norsigian the right to continue to market prints of the negatives in question as "real" Adams photographs; he must also point out that his negatives are not authorized by the Adams Trust.

honors and awards

- 1966: Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 1968: Conservation Service Award from the National Park Service (NPS)

- 1980: Presidential Medal of Freedom presented by US President Jimmy Carter

- 1981: Hasselblad Medal of the Erna and Victor Hasselblad Foundation presented by Carl XVI. Gustaf of Sweden

- 1982: Honorary Doctorate from Mills College , Oakland , California

- 1983: Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 1984: Renaming of the Minarets Wilderness in the Sierra Nevada to Ansel Adams Wilderness (posthumous)

Ansel Adams Award

Since 1971, the Sierra Club has presented the Ansel Adams Award for Conservation Photography to photographers who have worked primarily for the preservation and protection of nature. A well-known award winner is Frans Lanting from the Netherlands .

Famous photographs

The classics of landscape photography are:

- 1927: Monolith, The Face of Half Dome , (Monolith, wall of Half Dome) , Yosemite National Park, California

- 1932: Frozen Lake and Cliffs , ( Frozen Lake and Cliffs ) , Sequoia National Park, Sierra Nevada

- 1932: The Golden Gate before the Bridge , (The Golden Gate before the bridge) , San Francisco

- 1940: Surf Sequence , (Surf, a sequence) , six photographs coast at San Mateo, California

- 1941: Moonrise , (Moonrise) , Hernandez, New Mexico

- 1944: Clearing Winter Storm , (end of a winter storm) , Yosemite National Park, California

- 1944: Winter Sunrise , (sunrise in winter) , Sierra Nevada, seen from Lone Pine from California

- 1945: Mount Williamson , Sierra Nevada, as seen from Manzanar, California

- 1947: Mount McKinley and Wonder Lake (Mount McKinley and Wonder Lake) , Denali National Park, Alaska

- 1948: Sand Dunes, Sunrise , (sand dune in the sunrise) , Death Valley National Monument, California

- 1950: Early Morning, Merced River, Autumn (early autumn morning, Merced River) , Yosemite National Park, California

- 1950: Base of Upper Yosemite Fall , ( Upper Yosemite Falls ) , Yosemite National Park

- 1956: Half Dome, Yosemite Valley , Yosemite National Park, California

- 1960: Moon and Half Dome , (Moon and Half Dome) ,

- 1968: El Capitan, Winter Sunrise , El Capitan, winter sunrise , Yosemite National Park, California

Portrait photographs:

- 1933: Alfred Stieglitz, An American Place (Alfred Stieglitz in his gallery An American Place) , New York City

- 1937: Georgia O'Keeffe and Orville Cox (Georgia O'Keeffe and Orville Cox) , Canyon de Chelly National Monument

- 1940: Edward Weston , Carmel Highlands, California

- 1955: Farmer Family , (Farmer Family) , Melones, California

- 1961: Martha Porter, Pioneer Woman , (Martha Porter, wife of pioneer days) , Orderville, Utah

- 1974: Jacques-Henri Lartigue , Arles, France

Other motifs:

- 1929: Saint Francis Church, Ranchos de Taos , Taos, New Mexico

- 1958: Aspens , (Espen) , two photographs, Northern New Mexico

- 1956: Buddhist Grave marker and Rainbow , (Buddhist grave stones and rainbow) , Paia, Maui, Hawaii

- 1982: Graffiti, Abandoned Military Installation , (Graffiti in abandoned military facility) , Golden Gate Recreational Area, California

In 1965, Ansel Adams donated a selection of his works from the national parks and the photographs from the Manzanar internment camp to the Library of Congress's picture archive .

bibliography

Publications by Ansel Adams

- 1930: Taos Pueblo ; with Mary Hunter Austin (text); First edition 1930; Facsimile: New York Graphic Society, Boston / Little, Brown and Company, New York 1977, ISBN 0-8212-0722-9

- 1934: Yosemite. Tales and trails ; with Katherine Ames Taylor (text); San Francisco: HS Crocker, 1934

- 1934/1949: Making A Photograph ; First edition The Studio Publications Inc., 1934; in the fourth edition (1949) with a foreword by Edward Weston

- 1936/1940 The Four Seasons (Yosemite) , photographs by AA, ed. by Stanley Plumb, 1936 Yosemite Park and Curry Co .; fourth edition 1940

- 1939: Sierra Nevada, the John Muir Trail . The Archetype Press, Berkeley 1939; New edition Little, Brown and Company, New York 2006, ISBN 0-8212-5717-X

- 1940: A Pageant of Photography . Crocker Union, San Francisco 1940

- 1940: Illustrated Guide to Yosemite Valley ; together with Virginia Best Adams, Crocker-Union, San Francisco 1940

- 1941: Michael and Anne in the Yosemite Valley ; together Virginia Best Adams, Studio Publications Inc., 1941

- 1944: Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans ; New York: US Camera (1944); Reprint: Spotted Dog Press, 2002, ISBN 1-893343-05-7

- 1948: Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada ; Text by John Muir , ed. by Charlotte E. Mauk, Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1948

- 1948: Exposure Record . Morgan and Morgan, New York 1948

- 1948: Camera and Lens . New York Graphic Society / Morgan and Lester, New York 1948, reprint 1978, ISBN 0-8212-0716-4

- 1948: The Negative . New York Graphic Society / Morgan and Lester, New York 1948; New edition 2004, ISBN 0-8212-1131-5

- 1950: The Print . New York Graphic Society / Morgan and Lester, New York 1950; New edition 1995, ISBN 0-8212-2187-6

- 1950: Exposure record , Morgan & Morgan, New York 1950

- 1950: The Land of Little Rain ; Originally by Mary Hunter Austin (1912); New edition with photographs by AA; Houghton Mifflin and Company, Boston 1950

- 1951: My Camera in the National Parks , Houghton Mifflin and Company, Boston 1950

- 1952: Ansel Adams Natural Light Photography , New York Graphic Society / Morgan and Lester, New York 1952; New edition 1978 ISBN 0-8212-0719-9

- 1959: Yosemite Valley ; ed. by Nancy Newhall, 5 Associates, San Francisco 1959

- 1960: This Is The American Earth ; with Nancy Newhall, Sierra Club, San Francisco 1960, ISBN 1-199-54073-0

- 1967: Fiat Lux: The University of California ; with Nancy Newhall, McGraw Hill Book Company, 1967

- 1979: Polaroid Land Photography , New York Graphic Society, ISBN 0-8212-0729-6

- 1985: Ansel Adams: An Autobiography ; with Mary Street Alinder; New York Graphic Society / Little, Brown and Company, New York 1985; New edition 1996, ISBN 0-8212-2241-4

posthumously:

- Ansel Adams: Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs . Little, Brown and Company, 1997, ISBN 0-8212-1750-X

- Ansel Adams in Color ; ed. by Harry Callahan; Little, Brown and Company, Boston 1993, 2001 reissue, ISBN 0-8212-1980-4

- Conversations with Ansel Adams: oral history transcript / 1972-1975 With Introductions by James L. Enyeart and Richard M. Leonard. An Interview Conducted by Ruth Teiser and Catherine Harroun in 1972, 1974, and 1975. Regional Oral History Office Bancroft Library. Publisher: University of California Berkeley, Calif. c1978

German translations

- Ansel Adams: Autobiography ; with Mary Street Alinder, translated and annotated by Fritz Meisnitzer ; Christian Verlag, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-88472-141-0

- Ansel Adams: Meisterphotos - creation, technique, design of the 40 most famous pictures ; translated and annotated by Fritz Meisnitzer; Christian Verlag, Munich 1982; 3rd edition 1995, ISBN 3-88472-073-2

Textbooks:

- The positive as a photographic image ; with Robert Baker (illustrations); Christian Verlag, Munich 1984; 8th edition 1998, ISBN 3-88472-072-4

- The negative ; with Robert Baker (illustrations); Christian Verlag, Munich 1987; 9th edition 1998, ISBN 3-88472-071-6

- The camera ; with Robert Baker (illustrations); Christian Verlag, Munich 1982; 8th edition 2000, ISBN 3-88472-070-8

Illustrated books, monographs

- John Szarkowski (Ed.): Ansel Adams at 100: A Postcard Folio Book . Little, Brown & Company, 2001, ISBN 0-8212-2585-5 ; German edition at Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt / M. 2003, ISBN 3-86150-616-5

- John Szarkowski (Ed.): The Portfolios of Ansel Adams . Little, Brown & Company, 2006, ISBN 0-8212-5822-2

- Andrea G. Stillman (Ed.): Ansel Adams: 400 Photographs , Little, Brown and Company, New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-316-11772-2

- Andrea G. Stillman (Ed.): Untouched Landscapes , Christian Verlag GmbH, Munich, print: Gardner Lithograph 1990, ISBN 3-88472-187-9

Secondary literature

- Mary Street Alinder: Ansel Adams: A Biography . Key Porter Books, 1998, ISBN 0-8050-5835-4

- Mary Street Alinder: Letters 1916-1984 . Little, Brown and Company, Boston 2001, ISBN 0-8212-2682-7

- Jonathon Green: American Photography: A Critical History 1945 to the Present . Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York 1984, ISBN 0-8109-1814-5

- Franz-Xaver Schlegel: The life of dead things - studies of modern object photography in the USA 1914-1935 . 2 volumes, Art in Life, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-00-004407-8 (group f / 64: p. 215 ff., Ansel Adams: p. 231 ff.)

Ansel Adams in the film

- 2002: Ansel Adams: A Documentary Film ; Documentary produced by the Sierra Club about Adams' life and work in the series The American Experience on the US television channel PBS , directed by Ric Burns (running time: 100 min, color and b / w; first broadcast: April 21, 2002; released on DVD in 2004)

Web links

- Literature by and about Ansel Adams in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Ansel Adams in the German Digital Library

- Search for Ansel Adams in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Ansel Adams on kunstaspekte.de

- Ansel Adams in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Ansel Adams at photography-now.com

- Ansel Adams In: Times Topics of the New York Times (English)

- The Ansel Adams Gallery (English)

- Ansel Adams & The Sierra Club (English)

- American Experience - Ansel Adams: A Documentary Film (English)

- Ansel Adams at 100 Exhibition Feature in SFMOMA (English)

Notes and individual references

(Unless otherwise noted, excerpts from the biographical section are based on Ansel Adams and Mary Street Alinder: Ansel Adams: Autobiography ; in the German translation with notes by Fritz Meisnitzer, published by Christian Verlag, Munich, first edition 1985, ISBN 3-88472 -141-0 )

- ↑ When Ansel Adams learned in later years that his rich uncle had slowly driven his own brother, Ansel's father Charles, into bankruptcy through financial machinations, he deleted the middle name "Easton".

- ↑ Ansel Adams: Autobiography . Christian Verlag, Munich 1985, p. 13-15 .

- ↑ The moon crater was named after Charles Hitchcock Adams .

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 17

- ↑ Adams: Autobiography , pp. 44-45

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 21

- ↑ a b Adams: Autobiography , pp. 25-27

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 28

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 39

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 68

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 69

- ↑ a b Ansel Adams: Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, California. Afterimage Gallery, 1927, accessed June 27, 2008 .

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 74

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 75

- ^ Undated photograph by Albert Bender in the archives of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley , accessed July 20, 2008

- ↑ Adams: Autobiography , pp. 78-80, 88

- ↑ a b Adams: Autobiography , pp. 84-85

- ^ John Robinson Jeffers in: Microsoft Encarta

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , pp. 95f.

- ^ Ansel Adams: Meisterphotos , Christian Verlag, Munich 1984, 3rd edition 1995, p. 101

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 87

- ↑ a b Adams: Autobiography , pp. 102-103

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , 144

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 169

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 162

- ↑ Adams defined the term “fine image” in his later textbook Das Positiv .

- ↑ a b c Adams: Autobiography , p. 104

- ↑ Edward Weston's photographs fetch top prices at today's auctions. He has been considered one of the most expensive photographers since around the end of the 20th century. Source: Daniel von Schacky: The most expensive photographers today. Welt-Online, archived from the original on March 21, 2008 ; Retrieved June 13, 2008 .

- ↑ a b c Adams: Autobiography , pp. 114–116

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 178

- ↑ Arnold Genthe (1869–1942) is best known for his photographs of the great 1906 earthquake in San Francisco.

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 184

- ↑ a b Adams: Autobiography , p. 185

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 321

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 190

- ^ A b c Adams: Autobiography , pp. 249-250

- ^ A b Ansel Adams: Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico. anseladams.com, 1941, accessed December 30, 2019 . A signed gelatin silver print was auctioned on October 17, 2006 at Sotheby’s in New York for $ 609,600.

- ↑ In: Philip T. Ganderton: Return to Hernandez - A Short Essay on Moonrise, Hernandez by Ansel Adams. 2001, archived from the original on January 15, 2010 ; accessed on June 16, 2008 .

- ^ American Experience - Ansel Adams. PBS , 2002, accessed June 17, 2008 .

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 253

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 257

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , pp. 236-237

- ↑ Adams's Work at Manzanar. Library of Congress , accessed June 29, 2008 .

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 242

- ↑ Adams: Autobiography , pp. 261, 264-266

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , pp. 280-281

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 284

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 292

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 296

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 305

- ↑ a b Adams: Autobiography , pp. 315-316

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 320

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 322

- ^ Robert Hughes: Ansel Adams: Master of the Yosemite. Time Magazine, September 3, 1979, accessed June 20, 2008 .

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 327

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 329

- ↑ a b c d Beaumont Newhall: History of Photography . Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-88814-319-5 , p. 194-195, 198 .

- ^ A b John Pultz in: New History of Photography ; ed. by Michel Frizot, Könemann, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-8290-1327-2 , p. 484

- ↑ a b Ansel Adams: Das Positiv , Christian Verlag, Munich, 1984, p. 14

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 76

- ^ Ansel Adams: Das Negativ , Christian Verlag, Munich, 1983, p. 10

- ↑ Thomas Walter: The contrast-adapted B&W slide photography and the criticism. (PDF) May 17, 1997, archived from the original on November 10, 2007 ; Retrieved June 29, 2008 .

- ↑ Ansel Adams: Meisterphotos , pp. 13, 101

- ↑ Frank Bauchspiess: Direct selenium toning. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008 ; Retrieved July 10, 2008 .

- ↑ a b Adams in Color ; ed. by Harry Calahan; Little, Brown and Company, Boston 1993, blurb

- ↑ Photography of the 20th Century . Taschen, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-8228-8818-4 , pp. 19 .

- ↑ a b About Ansel Adams. (No longer available online.) In: Ansel Adams & the Sierra Club. Sierra Club , archived from the original on July 13, 2008 ; accessed on July 1, 2008 .

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 139

- ^ Robert Hughes: Ansel Adams: Master of the Yosemite. Time Magazine, September 3, 1979, accessed June 20, 2008 .

- ↑ a b c Tessa DeCarlo: Ansel Adams, the Artist Who Preceded the Celebrity. The New York Times, July 29, 2001, accessed July 1, 2008 .

- ^ John Pultz in New History of Photography , 1998, p. 486

- ↑ Sharp outlines in the moonlight . In: Der Spiegel . No. 51 , 1984 ( online ).

- ^ AD Coleman, Diane Dillon: William Mortensen: A Revival . 1998, ISBN 0-938262-33-5

- ^ Adams: Autobiography , p. 107

- ^ Jonathon Green: Ansel Adams. In: American Photography: A Critical History. Masters of Photography, 1984, accessed July 5, 2008 .

- ↑ Suspected Ansel Adams negatives / flea market photos could be worth millions. Spiegel Online , July 27, 2010, accessed July 29, 2010 . cf .: photographer Ansel Adams - negatives found on flea market for 200 million dollars. Die Zeit , July 28, 2010, accessed on July 29, 2010 .

- ↑ http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster/2011/03/ansel-adams-photographs-yosemite-rick-norsigian.html Los Angeles Times, March 15, 2011, accessed July 19, 2011

- ↑ Honorary Members: Ansel Adams. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed March 1, 2019 .

- ^ Ansel Adams Award Winners. (No longer available online.) The Sierra Club, archived from the original on May 28, 2008 ; Retrieved July 6, 2008 .

- ↑ The selection is based on Ansel Adams: Meisterphotos , Christian Verlag, Munich 1984, 3rd edition 1995

- ↑ Ansel Adams's Photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar. Library of Congress, accessed June 30, 2008 .

- ^ American Experience - Ansel Adams. PBS , 2002, accessed June 17, 2008 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Adams, Ansel |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Adams, Ansel Easton |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American photographer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 20, 1902 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | San Francisco |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 22, 1984 |

| Place of death | Carmel-by-the-Sea |