The Family of Man

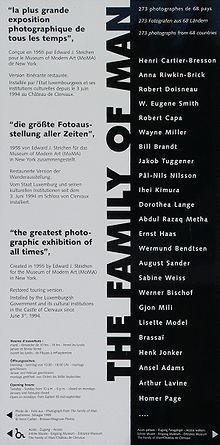

The Family of Man is a photo / text installation that was designed by Edward Steichen from 1951 for the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), where it was on view from January 24, 1955 . Steichen and his collaborators Wayne and Joane Miller initially selected ten thousand photos from over two million photographs, while his collaborator, civil rights activist Dorothy Norman, contributed accompanying text quotations from world literature and contemporary documents. Ultimately, 503 photos by 273 photographers from 68 countries made it to the exhibition. The exhibition was visited by more than ten million people worldwide and has been part of the world document heritage since 2003 .

The Family of Man has been a permanent exhibition at Clervaux Castle in Luxembourg (the homeland of Edward Steichen , where he was born in Bivange in 1879 ) since 1994 .

The basic idea

"The Family of Man" shows a comprehensive portrait of mankind in 32 topics, including z. B. love, faith, birth, work, family, children, war and peace. After the experiences of the war it was supposed to help promote understanding between people. It should also show what could be destroyed in the event of an impending nuclear war. At the end of the exhibition, there was a large photo of an atomic bomb explosion. Next to it was a warning from the philosopher and pacifist Bertrand Russell about the destructive power of the hydrogen bomb, which was later to find its way into the Russell-Einstein Manifesto (1955). Photography should serve as a universal language that all people understand. The exhibition should show that all people are equal and that every person, regardless of their class, regardless of race, regardless of culture, regardless of religion, regardless of age or gender, has dignity and all people have a common nature. The power of love and humanity should overcome hatred, violence and destruction. Some of the photos were from unknown amateurs; Most of the works exhibited were photographs by professional photographers and outstanding visual artists such as Mathew B. Brady , Dorothea Lange , Consuelo Kanaga , Robert Frank , Henri Cartier-Bresson , August Sander or Alfred Eisenstaedt . For the time, Steichen's installation showed an unusually large number of works by female photographers (including Margaret Bourke-White , Lee Miller , Lisette Model , Diane Arbus ) as well as photographs by relatively little-known African American artists (including Roy DeCarava , Gordon Parks ).

The exhibition

After the enormous success of the exhibition at MoMA , the pictures went on a world tour in several traveling versions, first to Tokyo , Berlin , Paris , Amsterdam , Munich , London and later even - during the Cold War - to Moscow and many other cities. The exhibition was celebrated by fellow artists, experts and the press. Steichen also received several awards. German photographer August Sander and writer Wolfgang Koeppen were full of praise for the exhibition . The German painter Gerhard Richter , who saw the exhibition in Berlin in 1955, was overwhelmed by the innovative power of the installation. There was also occasional criticism; some artists such as Saul Leiter ignored the invitation to the exhibition. By 1964, over nine million visitors in 38 countries on four continents (America, Europe, Asia and Africa) had seen the exhibition. In 1966 the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg received the last remaining walking version of the exhibition from the United States as a gift, just as Edward Steichen had requested. From 1974 to 1989 the exhibition was only partially shown in the castle of Clervaux . The pictures had been damaged by frequent transport and improper storage; they therefore had to be restored from 1989 to 1991 in over 2000 working hours. They were then shown again in Toulouse (January 1993), Tokyo (late 1993) and Hiroshima (early 1994), and since June 3, 1994 they have been on permanent display in Clervaux Castle. The installation of the exhibition should come as close as possible to the original design realized in MoMA.

"The Family of Man" was in the 2003 Memory of the World Register of UNESCO added.

The exhibition was closed from September 2010 to July 5, 2013 due to renovation work. The closing time was also used to restore each of the paintings.

The exhibition's humanistic image

Roland Barthes criticized in 1956 from the perspective of deconstruction , the humanist image of man of the exhibition. In Mythen des Everyday he described how the myth of “Adamism” and the human condition worked: “The myth of the human condition is based on a very old mystification that has always consisted of the foundation of history To set nature. "

As early as 1958, the German philosopher Max Horkheimer came up with a completely different interpretation when the exhibition opened at its stopover in Frankfurt. For him, the exhibition was able to show the complex diversity of the human family through the sensual abundance and wholeness of the pictures. From his point of view, the photos were characterized by a critical look that was transferred to the audience: "The individual pieces do not claim to be aesthetic works as much as discoveries. They show what everyone sees without being aware of himself. By directing the gaze to the known unknown, they bring the beholder into a new, more delicate relationship to things. Whoever has learned to see in this way, his senses are no longer focused on purposes, they are peculiarly changed and sharpened, In the future he will see differently, more vividly and in a more diverse way than before.This is indeed what the exhibition has in common with real artists, that it points perception in a new direction, which is no longer forgotten, how little can be done with it. "

In 1960 Siegfried Kracauer also saw an emancipatory potential in the intercultural orientation of the exhibition. For decades, however, Roland Barthes' negative attitude set the tone. Susan Sontag had literally repeated his core formulation in her collection of essays "On Photography" (1977). In the past two decades, Barthes' interpretation has been increasingly criticized and refuted. In his interpretation, Barthes had suppressed Steichen's pacifist stance, his criticism of nuclear weapons, his progressive interpretation of the question of women's rights and his commitment to civil rights. The Barthes researcher Jaqueline Guittard even voiced the suspicion in 2006 that Barthes, who did not discuss a single photograph, had not even visited the exhibition. In 2013, Ariella Azoulay criticized Barthe's dominant interpretation in that he did not take into account the polyphony of the installation and shortened the statement to the artist's intention and thus contradicted his own theory. The volume The Family of Man: Photography in a Global Age (2018), ed. by Gerd Hurm, Anke Reitz, and Shamoon Zamir, with previously unpublished documents and a variety of possible interpretive approaches, enables a renewed dialogue about this epoch-making exhibition. For Geoffrey Batchen, the “Family of Man” is currently the most important photography exhibition, the reception history of which should be re-examined critically and precisely, as the new documents call into question much of what was once considered reliable.

Photographers (selection)

Steichen's declared aim was to visually draw attention to the universality of human experience and the role of photography in its documentation. The exhibition brought together 503 photos from 68 countries. With 163 American and 70 European photographers, the ensemble takes a predominantly Western standpoint.

Dorothea Lange assisted her friend Edward Steichen in recruiting photographers with their FSA and Life connections, who in turn passed the project on to their colleagues. In 1953 she started "A Call to Photographers All Over the World":

“Show 'Man to Man' all over the world. Here we hope through visual images to reveal man's dreams and aspirations, his strength, his despair under evil. When photography brings these things to life, this exhibition is created in a spirit of passionate and devoted belief in man. We will achieve nothing less. "

The letter lists subjects that the photos could cover, although these categories are actually reflected in the final arrangement of the exhibition. Long works can be seen in the exhibition.

Steichen and his team relied in particular on Life archives for the photographs used in the last exhibition. These account for more than 20% of the total (111 out of 503). However, Steichen also searched for suitable images in 11 European countries, including France, Switzerland, Austria and Germany. In total, Steichen acquired 300 images from European photographers, many of them from the humanist group, which were shown for the first time in the 1953 European post-war photography exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The 1955 definitive exhibition international tour was sponsored by the now-defunct United States Information Agency. Its aim was to counter the Cold War propaganda by painting a better picture of American politics and values.

A number of participating photographers are included in the following list:

Source:

Texts used in the exhibition and in the book

The enlarged images of the various photographers were shown without explanatory captions and instead provided with quotes from James Joyce, Thomas Paine, Lillian Smith and William Shakespeare, selected by photographer and social activist Dorothy Norman. Carl Sandburg , Steichen's brother-in-law, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1951 and known for his biography of Abraham Lincoln, wrote an accompanying poetic commentary, which was also shown as text panels throughout the exhibition and included in the publication. The following quotes are excerpts from it:

- "There is only one man in the world and his name is All Men. There is only one woman in the world and her name is All Women. There is only one child in the world and the child's name is All Children. "

- "People! flung wide and far, born into toil, struggle, blood and dreams, among lovers, eaters, drinkers, workers, loafers, fighters, players, gamblers. Here are ironworkers, bridge men, musicians, sandhogs, miners, builders of huts and skyscrapers, jungle hunters, landlords, and the landless, the loved and the unloved, the lonely and abandoned, the brutal and the compassionate - one big family hugging close to the ball of Earth for its life and being. Everywhere is love and love-making, weddings and babies from generation to generation keeping the Family of Man alive and continuing. "

- "If the human face is 'the masterpiece of God' it is here then in a thousand fateful registrations. Often the faces speak that words can never say. Some tell of eternity and others only the latest tattings. Child faces of blossom smiles or mouths of hunger are followed by homely faces of majesty carved and worn by love, prayer and hope, along with others light and carefree as thistledown in a late summer wing. Faces have land and sea on them, faces honest as the morning sun flooding a clean kitchen with light, faces crooked and lost and wondering where to go this afternoon or tomorrow morning. Faces in crowds, laughing and windblown leaf faces, profiles in an instant of agony, mouths in a dumbshow mockery lacking speech, faces of music in gay song or a twist of pain, a hate ready to kill, or calm and ready-for- death faces. Some of them are worth a long look now and deep contemplation later. "

Catalog, exhibition

Catalog

- Jerry Mason (Ed.): The Family of Man. Prologue by Carl Sandburg . Museum of Modern Art, New York 1955

- (The United States Mission in Berlin): We All - The Family of Man . Prologue by Carl Sandburg, foreword by Edward Steichen. Booklet accompanying the exhibition at the Berlin School of Fine Arts as part of the Berliner Festwochen. Berlin undated (24 pages).

literature

- Edward Steichen : The Family of Man. Distributed Art Pubublishers (DAP), New York 1996, ISBN 978-0870703416

- Martin Thomas, Michael Neumann-Adrian: Belgium - Luxembourg. Bucher, Munich 1996, p. 85, ISBN 3-7658-1097-5

- Reinhard Tiburzy: Luxembourg. DuMont, Cologne 1997, pp. 154–155, ISBN 3-7701-3805-8

- Roland Barthes : The great family of people. In: Roland Barthes: Myths of everyday life. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1964. [Mythologies, 1957]

- Allan Sekula : The trade in photographs. In: Herta Wolf (Ed.): Paradigma Photography. Photo criticism at the end of the photographic age , Frankfurt am Main, 2002, pp. 255–290. [= The Traffic in Photographs , in: Art Journal, Spring 1981, pp. 15–21.]

- Claudia Gabriele Philipp (di Gabriele Betancourt Nuñez): The exhibition "The Family of Man" (1955). Photography as a world language. In: Photo History, 7th year, No. 23, Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 45–62

- Sarah Goodrum: A Socialist Family of Man . Rita Maahs' and Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler's Exhibition On Human Happiness . In: Zeithistorische Forschungen 12 (2015), pp. 370–382.

Web links

- Official homepage of The Family of Man

- Family of Man on UNESCO's World Document Heritage Site

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gerd Hurm : Hurm, Gerd, (ed.); Reitz, Anke, (ed.); Zamir, Shamoon, (ed.) (2018), The family of man revisited: photography in a global age, London IBTauris, ISBN 978-1-78672-297-3 , 34, 41

- ^ Family of Man. In: Memory of the World - Register. UNESCO , 2003, accessed July 5, 2013 .

- ↑ Steichen Collections: The Family of Man , accessed September 18, 2016.

- ↑ Gerd Hurm : Hurm et al., 32

- ↑ Gerd Hurm : Hurm et al., 41, 110

- ↑ Gerd Hurm : Hurm et al., 10, 71, 73

- ↑ FERMETURE pour rénovation & restauration ( Memento of August 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Press release on the website of the exhibition of September 27, 2010 (French)

- ↑ “Family of Man” in focus: man in all his facets . In: Luxemburger Wort , July 4, 2013, accessed the day after.

- ↑ Roland Barthes : The great family of people. In: Roland Barthes: Myths of everyday life. Frankfurt / M., Suhrkamp. 1964. p. 17

- ↑ Gerd Hurm : The rhetoric of the details. schwarz auf weiss.org, article 214, December 13, 2015.

- ^ Max Horkheimer, opening of the photo exhibition The Family of Man - We all (1958). In: Alfred Schmidt (ed.): Collected writings. Vol. 13. Frankfurt a. M. 1989, p. 36

- ↑ Hurm et al., P. 25, 38

- ↑ Jacqueline Guittard in Hurm et al., P. 24

- ^ Ariella Azoulay in Hurm et al., P. 23

- ^ Matthias Kolb, "Friede auf Erden", Süddeutsche Zeitung, June 2, 2018, p. 51

- ↑ Geoffrey Batchen in Hurm et al., Back of the book cover

- ↑ a b c d Kristen Gresh: The European Roots of "The Family of Man". In: History of Photography. 2005, 29, (4): 331-343, DOI: 10.1080 / 03087298.2005.10442815 .

- ^ Turner, Fred (2012). 'The Family of Man and the Politics of Attention in Cold War America', in Public Culture 24: 1 Duke University Press doi: 10.1215 / 08992363-1443556

- ↑ Dorothea Lange, letter, January 16, 1953, quoted in Szarkowski, The Family of Man , p. 24.

- ↑ Alise Tlfentale (2015) in Šelda Pukīte (editor) and Latvian National Museum of Art and Luxembourg National Museum of History and Art. Edvards Steihens. Photography: Izstades catalogs (Edward Steichen. Photography: Exhibition catalog). Neputns Publishing House and Latvian National Museum of Art

- ↑ Photography Now: The Family of Man - UNESCO Memory of the World , accessed September 18, 2016.

- ^ Gerd Hurm: Hurm, Gerd, 1958-, (editor.); Reitz, Anke, (editor.); Zamir, Shamoon, (editor.) (2018), The family of man revisited: photography in a global age, London IBTauris, p. 11, ISBN 978-1-78672-297-3