Edward Steichen

Edward Jean Steichen (born March 27, 1879 in Béiweng , Grand Duchy of Luxembourg ; † March 25, 1973 in West Redding , Connecticut ) was an artist , photographer and curator who had a considerable influence on the development of photography and the transfer of art between Europe and the USA in the early modern. With The Family of Man , Steichen conceived the most influential exhibition in the history of photography .

Life

Eduard Jean Steichen was born in Béiweng in Luxembourg in 1879 as the first child of Marie Kemp (1854–1933) and Jean-Pierre Steichen (1854–1944). In 1880 Jean-Pierre Steichen emigrated to the USA . Marie Steichen followed in January 1881 with her son Edward. The family moved via Chicago to the mining town of Hancock, Michigan . The second child, Lilian, was born in 1883 (1883–1977). Mary Kemp Steichen (names anglicized with emigration) first worked as a tailor and then opened a hatmaker shop with up to ten employees. Jean-Pierre Steichen cultivated a garden with the cultivation of fruits and vegetables . From 1888 to 1894 Edward attended Pio Nono College boarding school in St. Francis , Wisconsin . In 1889 the family moved to Milwaukee .

1903 married Edward Steichen and the musician Clara Smith (1875-1952). In 1904 the daughter Mary (1904–1998) was born, followed in 1908 as the second child Kate Rodina (1908–1988). The couple separated in 1914 and the divorce was declared in 1921. In 1923 Steichen married the actress and photographer Dana Desboro Glover (1894–1957). After Dana's death, Edward married Joanna Taub (1933-2010) in 1960.

Edward Steichen died on March 25, 1973 in West Redding, Connecticut.

education

Edward Steichen traveled to the World's Fair in Chicago in 1893 at the age of 14 . Shortly afterwards he bought a camera and learned how to take photos on his own. In 1894 Edward began training in typesetting , then in the design department at the American Fine Art Company in Milwaukee . The company designed commercial graphics for the American market. Edward had his first experience with design before his apprenticeship: he designed advertising posters, shop windows and hats for his mother's salon. Steichen's fundamental appreciation for the means and benefits of the graphic arts and crafts were laid here. Success came quickly: in 1897 Steichen was awarded the National Education Association's prize for designing an envelope.

Milwaukee Art Students League

While still studying, Steichen founded the Milwaukee Art Students League together with friends in 1896. Steichen was active in the first professional art association in Milwaukee as president for the interests of young artists. In 1899 Steichen submitted three photographs for the Second Philadelphia Salon. The jurors Gertrude Käsebier , Fred Holland Day and Clarence H. White accepted his work. Especially Portrait Study (1898), Steichen's photographic self-portrait as a young artist, caused a sensation in the exhibition and then internationally. On Clarence White's advice, Steichen submitted ten photographs for the 1900 Chicago Salon . Two of his works were exhibited there. Steichen was stylistically versatile in his early work, but above all connected to Pictorialism .

Out and about in Europe

Equipped with a letter of recommendation from Clarence H. White, Steichen met Alfred Stieglitz in New York in 1900 . Stieglitz bought three works by the young photographer. Steichen traveled on from New York for his first visit to Europe . For a short time he studied at the Académie Julian in Paris . He visited the Paris World Exhibition , the Louvre and was enthusiastic about the works of Auguste Rodin . Steichen went to Vienna and contacted Fred Holland Day in London . Day included 21 works by Steichen in the exhibition The New School of American Photography . The show attracted a lot of attention and Steichen's Portrait Study (1898) was the subject of controversy. In 1901, Day showed The New School of American photography in a modified version in Paris, with an even greater number of Steichen's photographs. Steichen became the "internationally celebrated child prodigy". At the same time, Steichen exhibited a painting in Paris: his portrait of Fred Holland Day was accepted by the Societé des Beaux Arts at the Salon de 1901 .

The first solo exhibition Monsieur Eduard J. Steichen received Steichen in 1902 in Paris. In the Maison des Artistes he showed retouched and non-retouched photographs as well as paintings alternating in order to emphasize the equality of the two art forms. Steichen thus abolished the firmly established academic separation between the fine arts and photography. His reputation spread quickly, and invitations to exhibitions in Europe and the USA , prizes and awards followed. Among other things, Belgium acquired Steichen's The Black Vase (1901), the first ever photograph for a museum.

In Paris , Steichen met numerous avant-garde artists and intellectuals, the photographers Alvin Langdon Coburn , Frank Eugene , Gertrude Käsebier , Mary Devens , Elise Pumpelly Cabot and Margaret Russell. He made the acquaintance of Auguste Rodin , photographed the artist and his works. In Paris Steichen met the Belgian writer and naturalist Maurice Maeterlinck , with whose work he was already familiar. At the suggestion of his sister traveled to Steichen Socialist Congress in Stuttgart to August Bebel and Karl Liebknecht to photograph.

Camera work

In 1902 Steichen returned to the USA . He founded a photo studio in New York and established himself as a photographer. Alfred Stieglitz called as a mouthpiece of the New York Photo-Secessionist magazine Camera Work to life . He entrusted Edward Steichen with the typographic layout and title design. Steichen thus shaped the first impression of the magazine for over 15 years and 50 issues. His influence extended far beyond the graphic design. Over 60 of his photographs have been reprinted over time, and five special editions of the magazine exclusively showed his work. Not least because of Steichen's ongoing contacts in the art scene (such as Henri Matisse and Sarah and Leo Stein ), Camera Work offered contemporary artists and intellectuals a forum. His essay Ye Fakers appeared in the first edition in January 1903 . Steichen expressed his conviction that a photo by no means only shows a mechanical, objective image of reality, but is shaped by the subjective design of the photographer.

Gallery 291

1905 founded Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz in 291 Fifth Avenue , the gallery 291 as a presentation space for the New York Photo Secession. Alfred Stieglitz wrote in 1913: “We would like to take this opportunity to express once again how much we owe Steichen thanks. The work of '291' could not have been achieved to such full extent without his active participation and constructive cooperation, which he has always done completely unselfishly. It was he who originally associated '291' with Rodin [...] and with Matisse ”. Together with his wife Clara, Steichen had worked out the plan for the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession : Against the prevailing zeitgeist, the exhibits were to be arranged geometrically in simple rooms without decoration and well-lit at eye level. Steichen's connections in the avant-garde art scene expanded the spectrum beyond photography. With his idea of showing both painters and photographers, the gallery played an important role in promoting modern, European visual art in the USA - well before the Armory Show in 1913. Between 1906 and 1914, Steichen commuted between Europe and the USA and acted as intermediary direct contact to the artists numerous exhibitions in the gallery 291 . In 1907, drawings by Auguste Rodin were presented in the USA for the first time , and the exhibition met with enormous feedback. In 1908 Henri Matisse was able to exhibit for the first time outside of Paris in Galerie 291. Works by Paul Cézanne (1911), Pablo Picasso and George Braque (1911, 1914), Éduard Manet , Auguste Renoir , Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec , Henri Rousseau (1910) and Constantin Brâncuși (1914) were shown. Steichen prepared the construction of the exhibition from France using precise installation sketches. In 1914, 291 showed an early exhibition of African masks and cult objects, and subsequently Steichen combined Cubist works by Picasso and Braque with African cult objects and the object trouvé of a wasp nest.

Steichens himself continued to work as an artist. His photographs and paintings have been shown in numerous exhibitions and have received multiple awards. In 1906 his painting Apple Bloom appeared on the cover of Vogue . In 1907 Steichen was one of the first to experiment with the new technology of color photography.

Plant growers in Voulangis and West Redding

The Steichen family leased a farm in Voulangis near Paris in 1908 . Steichen worked there as a photographer and painter and remained active in art education. The courtyard served artist friends as a place of residence and exhibition. Stylistically, Steichen turned more and more from pictorialism and further towards objectivity, his paintings showed the influences of Fauvism . This phase of his work is difficult to reconstruct: a large part of the negatives and photo prints were lost in the turmoil of the First World War, and Steichen also destroyed his early pictures in Voulangis.

Steichen also worked intensively as a plant and vegetable breeder in Voulangis. His delphinium varieties received the gold medal of the Societé Nationale d´Horticulture de France in 1913. In the same year Steichen was awarded for the best potato harvest in the Seine et Marne department.

When the German troops entered France , the Steichen family had to leave the farm in Voulangis and return to the USA .

Working with nature remained indispensable for Steichen: in 1928 he bought a 60 hectare site in West Redding, Connecticut . At the Umpawaug Plant Breeding Farm , Steichen continued his experiments on breeding and growing plants. In June 1936, in the first Bio-Art installation, he showed larkspurs grown on his farm for a week at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The museum announced the show of “the very well-known photographer” as a “very unusual… show” and emphasized in a press release from June 22, 1936: “To avoid confusion, it should be noted that the museum actually shows larkspurs - no paintings or Photographs. The flowers will appear “personally”. ”In 1936 he also photographed Walden Pond in Massachusetts for an illustrated edition of Henry David Thoreau's dropout and eco-bible Walden (1854).

Photographer at war

When the USA entered World War I , Steichen volunteered in 1917. As an air reconnaissance employee , he was responsible for photographing enemy positions in France . Steichen also volunteered during the Second World War in 1941. As head of a photography department in the US Navy in the Pacific, he was responsible for logging the war at sea. While he was still on the front, Steichen curated two exhibitions for the Museum of Modern Art in collaboration with Carl Sandburg and Herbert Bayer: The Road to Victory (1942) and Power in the Pacific (1945). Together with William Wyler he worked on the production of the film The Fighting Lady about everyday life on an aircraft carrier. The Fighting Lady received an Oscar for best documentary in 1944 . Together with Thomas J. Maloney, Steichen published the illustrated book US War Photographs: Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Harbor in 1946 . Steichen described in 1963 that his involvement in the wars should promote the desire for peace in the viewers of the photographs. “My feelings of aversion to the war hadn't let up since 1917. But over the years I had gradually come to believe that if a real image of war could be photographed and presented to the world, it might help end the specter of war. This thought drove me to take part in a photographic recording of the Second World War ”.

Fashion photographer: Vogue and Vanity Fair

In 1911, the publisher Lucien Vogel offered Edward Steichen to photograph Paul Poiret's fashion for Art et Décoration magazine . Steichen's elegantly staged photos were published in April 1911 and are considered the beginning of modern fashion photography. In 1919 Isidora Duncan invited Edward Steichen on a trip to Greece : Steichen focused in the recordings on the relationship between the dancers in antique robes and the architecture of the Acropolis .

Eventually Steichen turned to fashion and portrait photography. In 1922, the publisher Condé Nast offered him to work as chief photographer for Vogue and Vanity Fair . Until the 1930s, Steichen was considered the highest paid photographer. He staged the celebrities of his time: Greta Garbo (1928), Gloria Swanson (1924), Gary Cooper , Agnes Geraghty (1929), Winston Churchill (1934). Steichen used his influence so that photographs of Afro-American personalities could be published: In 1924, his picture of jazz singer Florence Mills was printed as the first full-page portrait in the Vanity Fair , followed in 1933 by a full-page portrait of actor and civil rights activist Paul Robeson. In 1932 Steichen designed the first colored cover photo for Vogue . Steichen staged around 1000 portraits and just as many fashion photos by 1937.

In 1923 Steichen began teaching at the Clarence White School of Photography in New York. To this end, he was under contract with the advertising agency J. Walter Thompson, designed fabric samples for the Stehli Silks Corporation, and shot advertising for lighters and shoes. Steichen emphatically defended his comprehensive concept of art and his understanding of an objective, functional aesthetic. Edward Steichen: “Something is beautiful when it serves its purpose, when it works. In my opinion, a modern refrigerator is an object that exudes beauty. "

During his time for Vogue and Vanity Fair , Steichen also dealt with architectural photography, among other things. An example of this is his recording of Maypole (1932). Steichen remained very well connected internationally: for film and photo , a show curated by László Moholy-Nagy for the Deutscher Werkbund in Stuttgart , he put together the American selection in 1929 with Edward Weston . He showed works by Berenice Abbott , Anton Bruehl, Paul Outerbridge and Charles Sheeler , among others .

Children's books

As early as the 1920s , Steichen was collecting ideas for a children's book that was populated by a series of abstract, geometric figures, the Oochens . At the beginning of the 1930s, he and his daughter Mary published two small photo books for children: The First Picture Book (1930) and The Second Picture Book (1931).

US Camera Annual

When Thomas J. Maloney was planning to publish the US Camera Annual as publisher in 1934 , he initially appointed Steichen as chairman of the selection jury, and from 1938 to 1946 as the sole juror. Steichen promoted social documentary and socially critical photography: Dorothea Lange was represented in the first issue of the magazine in 1935 with White Angel Breadline (1932) and in 1936 with Migrant Mother (1936). In 1938 Steichen designed an edition of the US Camera Annual with photographs from the time of the Great Depression, which were shown in the 1938 exhibition First Photographic Exposition in New York's Grand Central. The US Farm Security Administration (FSA) commissioned photographers from 1935 to 1941 to document the effects of the Depression in rural areas. Involved were u. a. Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans , Ben Shahn , Carl Mydans and Arthur Rothstein . The First International Photographic Exposition 1938 was shown at New York's Grand Central Palace. Thanks to Steichen's reputation and commitment, documentary photography, which had previously been neglected as an artistic form of expression, gained further respect. For him, the photographs of Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Russell Lee and others were "the most impressive human documents that have ever been shown in pictures".

Director at the Museum of Modern Art

Time and again, Steichen was in contact with the Museum of Modern Art as an artist and curator through exhibitions. In 1947 Edward Steichen was appointed director of the photography department of the Museum of Modern Art at the instigation of Thomas J. Maloney. In the 15 years that followed, up to 1962, Steichen curated 44 photo exhibitions in a wide variety of genres. Steichen gave an overview of the current state of photography in 1948 with two exhibitions: In and Out of Focus: A Survey of Today's Photography and 50 Photographs by 50 Photographers . With the group exhibition Six Women Photographers , the first group exhibition for women, Steichen, as a curator, set a signal for equal rights for women photographers in 1949. In 1950 Steichen invited under the motto What is Modern Photography? to a public symposium with contemporary photographers Margaret Bourke-White , Irving Penn , Lisette Model and Walker Evans . In 1961 the MoMA showed the retrospective Steichen the Photographer .

As director of the photography department, Steichen systematically supported young artists such as Robert Frank , Lee Miller , Harry Callahan , Roy DeCarava , Consuelo Kanaga and Stephen Shore through exhibitions and acquisitions . The MoMA buys the first museum of photographs under his leadership, among others Robert Rauschenberg on.

With the exhibition The Bitter Years , Steichen said goodbye as director in 1962 . The Bitter Ye ars once again took the social documentary photographs from the time of the Great Depression as their subject. In addition to human need, the exhibition also focused on the exploitation and destruction of nature.

The Family of Man

At the beginning of the 1950s, Steichen implemented an idea from the global economic crisis: an exhibition as a manifesto of peace and equality for all people. Steichen and a team selected 503 photographs by around 270 photographers from 70 countries. The installation The Family of Man clarified the principles of the United Nations and the UN Declaration of Human Rights . "THE FAMILY OF MAN is planned as an exhibition of photography portraying the universal elements and emotions and the oneness of human beings throughout the world. It is probably the most ambitious and challenging project photography has ever faced and one for which, I believe, the art of photography is uniquely qualified ". During the Cold War era , images of people from a wide variety of cultures were contrasted by capturing the explosion of a hydrogen bomb . This great parade of human emotions and feelings, seen in people, characterized the dignity and hope wherever they were found by photographers all over the world, is climaxed at the end of the exhibition by a series of photographs which dramatically rise one of the greatest challenges of our time - the hydrogen bomb and what it may mean for the future of the family of man. Nine photographs of questioning faces, more No. 3 triptychs of three children, three women and three men are shown with a quotation from Bertrand Russell, "... the best authorities are unanimous in saying that a war with hydrogen bombs is quite likely to put an end to the human race .. .. there will be universal death - sudden only for a fortunate minority, but for the majority a slow torture of disease and disintegration. "

The exhibition was a resounding success when it opened at MoMA in 1955. In four months, around 270,000 people visited the installation in New York. The Family of Man was then exhibited in almost 40 countries around the world and the catalog sold four million times. The exhibition has been a UNESCO World Document Heritage since 2003 .

Permanent exhibitions in Luxembourg

In 1952 Steichen traveled to his homeland to win Luxembourg as the starting point for the traveling exhibition The Family of Man . The Grand Duchy rejected the idea, saying that photography was not art. In 1966, through the mediation of the journalist Rosch Krieps, a donation was arranged. The last surviving version of the Family of Man (1964) and The Bitter Years (1967) was transferred to the Grand Duchy. In 2004 the Ministry of Culture launched the Edward Steichen Award . In Luxembourg, The Family of Man in Clervaux has been shown in permanent exhibitions since 1994 and The Bitter Years in Dudelange since 2012 .

reception

When Auguste Rodin called Steichen a “very great artist and the leading, greatest photographer of our time” in 1908, photography was not yet accepted as an art form.

When the Armory Show in New York opened in 1913 with 1,600 works by European and American artists, Steichen was not invited: the curators had categorically excluded works by photographers, and no painting by Steichen was included in the exhibition. Like many photographers at the beginning of the 20th century , Steichen was initially interested in having photography included in the canon of the visual arts . “When I got interested in photography, I thought that was the greatest thing of all. My idea was that it had to be recognized as an art. Today I don't give a damn about it. The task of photography is to explain humanity to human beings and to explain each human being to themselves. ”But his contemporaries considered Steichen's wide-ranging interests to be insufficiently academic. The independence with which Steichen moved between the art forms, his work as a freelance artist and as a paid contract artist, his early interest in fashion photography and social documentary work led to some violent rejection.

The Family of Man curated by Steichen also met with opposing reactions. August Sander saw the installation as “the greatest work that photography has brought to light”. While the French cultural scientist Roland Barthes covered the exhibition in 1956 with what had been dominant for a long time, Max Horkheimer pointed out in his opening speech in 1958 in Frankfurt that the viewer “... will see in the future differently, more vividly and more diverse than before . What the exhibition has in common with real artists is that it points perception in a new direction ”. A reassessment of Steichen's work began only after the opening of the permanent exhibitions in Luxembourg .

Filmography

- 1966 This is Edward Steichen, CBS, scripted by Jane Kramer

- 1995 Edward J. Steichen, documentary Claude Waringo

Art theoretical writings

- Edward Steichen: "Ye Fakers", Camera Work 1, 1903: p. 48. Edward Steichen: "The FSA Photographers". US Camera Annual 1939 . New York 43-66.

Quotes

“When I took up photography, I wanted to see it recognized as an art. Today I wouldn't give a chanterelle for this goal. The photographer's job is to explain people to people and help them to recognize themselves. "

Works

The following recordings are in the public domain due to the Google Arts & Culture project and Steichen's work with the US Navy . No fashion or advertising photos from the 1920s or 1930s are available.

Moonlight recordings, act

Artist portraits

War reporting

Archive and exhibitions

archive

1964 Edward Steichen Photography Center, Museum of Modern Art, New York

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York

Exhibitions

- In high fashion, 1923–1937. First comprehensive exhibition of the original prints of Steichen's work for the fashion and glamor industry at the Kunsthaus Zürich from January 11th to March 30th, 2008

- Edward Steichen: Lives in Photography , Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume , Paris, 2007, then:

- A life for photography . Retrospective of Steichen's oeuvre at the Musée de l'Elysée in Lausanne from January 18 to March 24, 2008.

- In high fashion . Exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg from October 11, 2008 to January 4, 2009.

- Goldfinch, Steichen, beach . Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City from November 10, 2010 to April 10, 2011.

- New York Photography. From Goldfinch to Man Ray . Exhibition at the Bucerius Kunst Forum , Hamburg, from May 17 to September 2, 2012

Permanent exhibitions

- Banque et Caisse d'Epargne de l'Etat tunnel , Luxembourg ( 360 ° panorama )

- The Family of Man, Center National de l´Audiovisuelle, Clervaux, Luxembourg (1994)

- The Bitter Years, Dudelange, Luxembourg (2012)

- Salle Steichen, Musée National d´Histoire et d´Art, Luxembourg City (2015)

Auction of his work

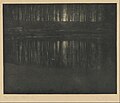

On February 14, 2006, one of three existing enlargements of Edward Steichen's photo The Pond - Moonlight was auctioned at Sotheby’s , New York City for $ 2.928 million. This was the highest auction price for a photograph to date - until March 2007, when an unknown bidder paid $ 3.3 million for the work 99 cent II, Diptych by Andreas Gursky .

literature

- How Edy was after Jonk. Published in 2004 by the Luxembourg Ministry of Education, Vocational Training and Sport. Available online , PDF, 2.5 MB.

- AD Coleman, Catherine Coleman, Ronald J. Gedrim, Patricia Johnston, Olivier Lugon, Pamela Roberts, Joanna T. Steichen, Todd Brandow (Eds.), William A. Ewing (Eds. And Foreword): Edward Steichen. A life for photography . Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2007, ISBN 978-3-7757-2065-6

- Joel Smith: Edward Steichen: The Early Years . Princeton University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-691-04873-8

- Todd Brandow and William A. Ewing (eds.): Edward Steichen: A life for photography . Ostfildern 2007.

- Elsen, Thomas and Christof Trepesch (eds.): Edward Steichen: The artist portraits . Berlin 2014.

- Max Horkheimer: "Opening of the photo exhibition The Family of Man - We All (1958)". Collected Writings. Vol. 13. Ed. Alfred Schmidt. Frankfurt 1989. 30-37.

- Gerd Hurm, Anke Reitz and Shamoon Zamir (eds.): The Family of Man Revisited: Photography in a Global Age . London 2018.

- Gerd Hurm: Edward Steichen . Luxembourg 2019.

- Patricia A. Johnston: Real Fantasies . Berkeley 1997.

- Krieps, Rosh. Steichen story I / II. Luxembourg 2004.

- Penelope Niven: Steichen: A Biography . New York 1997.

- Eric J. Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition . Albuquerque 1995.

- Edward Steichen: The Family of Man. New York 1955.

- Edward Steichen: A Life for Photography . Düsseldorf 1965.

- Joanna T. Steichen: Steichen's Legacy: Photographs, 1895-1973 . New York 2000.

Web links

- Edward Steichen on kunstaspekte.de

- Edward Steichen at photography-now.com

- Literature by and about Edward Steichen in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Edward Steichen in the German Digital Library

- Search for Edward Steichen in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- The Bitter Years exhibition in Dudelange

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hurm, Gerd: Edward Steichen . Editions Luxembourg, Luxembourg 2019, ISBN 978-99959-2040-1 .

- ^ 'The admiration one feels for something strange and uncanny': Impressionism, Symbolism, and Edward Steichen's Submissions to the 1905 London Photographic Salon. Retrieved May 8, 2020 .

- ↑ Edward Steichen: Ye Fakers . In: Camera Work . tape 1 , 1903, p. 48 .

- ↑ Hurm: Edward Steichen . 2019, p. 109 .

- ↑ Michael Torosian: Steichen: Eduard et Voulangis, The Early Modernist Period 1915-1923 . 2011.

- ↑ Edward Steichen Is Dead At 93.Retrieved May 4, 2020 .

- ↑ MoMA: Press Release 32505. Retrieved May 4, 2020 .

- ↑ Hurm, Gerd .: Edward Steichen. Editions Luxembourg, Luxembourg 2019, ISBN 978-99959-2040-1 , pp. 92 .

- ^ Coleman, Allan D., Brandow, Todd ,, Steichen, Edward: Edward Steichen - a life for photography: [on the occasion of the exhibition Edward Steichen: Lives in Photography, Jeu de Paume, Paris, October 9th - December 30th, 2007 ... Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, June 24th - September 22nd, 2008] . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2007, ISBN 978-3-7757-2065-6 .

- ^ Paul Martineau: Icons of Style: A Century of Fashion Photography . tape 40-41 . Los Angeles 2018, pp. 20 .

- ↑ Edward Steichen. Retrieved May 4, 2020 .

- ^ Carl Sandburg: Steichen the Photographer . Ed .: Steichen the Photographer. New York 1961.

- ↑ Edward Steichen. Retrieved May 4, 2020 .

- ↑ Edward Steichen. Retrieved May 4, 2020 .

- ↑ Hurm, Gerd: Edward Steichen . Editions Luxembourg, Luxembourg 2019, ISBN 978-99959-2040-1 , pp. 109 .

- ↑ Hurm, Gerd: Edward Steichen . Editions Luxembourg, Luxembourg 2019, ISBN 978-99959-2040-1 , pp. 124 .

- ↑ Hurm, Gerd: Edward Steichen . Editions Luxembourg, Luxembourg 2019, ISBN 978-99959-2040-1 , pp. 153 .

- ^ MoMA Press Release: Edward Steichen . January 31, 1954.

- ↑ MoMA Press Release: 325965 . January 26, 1955.

- ↑ Hurm, Gerd: Edward Steichen . Editions Luxembourg, Luxembourg 2019, ISBN 978-99959-2040-1 , pp. 143 .

- ^ Penelope Niven: Steichen . New York 1997, p. 292 .

- ↑ Steichen, 1969 cit. n. Hurm (2019, p. 156), see Hurm, Gerd: Edward Steichen . Editions Luxembourg, Luxembourg 2019, ISBN 978-99959-2040-1 , pp. 156 .

- ↑ Patricia A. Johnston: Real Fantasies . Berkeley, 1997, pp. 221 .

- ↑ Gerd Hurm, Anke Reitz, Shamoon Zamir (eds.): The Family of Man Revisited: Photography in a Global Age . London 2018, p. 74 .

- ↑ Roland Barthes: "Press photographs can never be art photographs": The Photographic Message . New York 1977, p. 18 .

- ^ Max Horkheimer: "Opening of the photo exhibition The Family of Man - We all (1958)" . In: Alfred Schmidt (ed.): Collected writings . tape 13 . Frankfurt 1989, p. 36 .

- ↑ Hurm, Gerd: Edward Steichen . Editions Luxembourg, Luxembourg 2019, ISBN 978-99959-2040-1 , pp. 146 .

- ↑ Eric Sandeen: Picturing an Exhibition . Albuquerque 1995.

- ↑ Google Arts & Culture: Edward Steichen , 14 selected works, accessed on September 18, 2016.

- ^ Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand , The Metropolitan Museum of Art ( English ), accessed February 12, 2011

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Steichen, Edward |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Steichen, Edward Jean (full name); Steichen, Edouard Jean |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Luxembourg photographer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 27, 1879 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Béiweng , Grand Duchy of Luxembourg |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 25, 1973 |

| Place of death | West Redding , Connecticut |