Camille Pissarro

Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro (born July 10, 1830 in Charlotte Amalie , Danish West Indies today: American Virgin Islands , † November 13, 1903 in Paris ) was one of the most important and productive painters of impressionism . He is the progenitor of the artist family Pissarro .

Life

Parental home, childhood and youth

Camille's father, Abraham (Frederic) Gabriel Pissarro came from a Marran family from Bragança in Portugal and had fled to Bordeaux with his parents as a child before the Inquisition . A large community of Sephardic Jews existed in Bordeaux . Camille's mother, Rachel Manzano-Pomié, had Spanish ancestry and was from the Dominican Republic . In 1824 the father's family emigrated to the Antilles Islands . One of the first Jewish communities in the New World existed in Charlotte Amalie , the capital of the Danish West Indies on St. Thomas . There the father ran a hardware store.

The family continued to have permanent connections to Bordeaux. At the age of twelve, Camille Pissarro was sent to a boarding school in a suburb of Paris. Even at this age he showed a great interest in drawing and his drawing teacher Auguste Savary , who was also the principal and founder of his school and a respected salon painter , encouraged Pissarro in this inclination. Pissarro filled his notebooks with drawings of palm trees and plantations in his homeland.

In 1847 his father brought him back to the West Indies to introduce him to the family business. However, Pissarro preferred to spend every free minute at the port and draw. There he met the Danish painter Fritz Melbye , who, despite the age advantage of only four years, was already an established painter who had exhibited several times in Copenhagen . Melbye recognized Pissarro's talent and encouraged him. Despite his father's opposition, Pissarro joined Melbye when he traveled to Venezuela in 1852 .

The young artist

In Caracas , Melbye and Pissarro rented a house together and Pissarro drew the city life, the market and the buildings, the taverns, but also the rural life and the vegetation in the area. In 1854 he returned to St. Thomas. Eventually he managed to convince his father to help him decide to devote his life to painting. In September 1855 he finally left St. Thomas and traveled to Paris. At the world exhibition there , he was able to admire almost 5,000 works of painting, including pictures by Eugène Delacroix , Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Camille Corot .

Pissarro became a student of Corot. He also went to the painter Anton Melbye , Fritz Melbye's brother. Urged by his father, he also took lessons from masters at the École des Beaux-Arts , but their dogmatic approach did not appeal to him. Instead, he preferred to work with young colleagues who met in the cafés and discussed realism and painting in the open air. In 1858 he began to appropriate these subjects and painted in the woods north of Paris. One of these pictures, Landscape near Montmorency , was accepted at the Salon of 1859, but did not attract much attention there.

In 1857 his parents moved back to France. Pissarro lived with them again in their house in Montmorency . In 1859 Julie Valley joined the parental household as a servant. She and Camille began a relationship that resulted in two illegitimate children. In 1859 Pissarro met Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne at the Académie Suisse , a free painting school .

The middle years

In the mid-1860s, Pissarro began to break away from his teacher Corot and find his own style. In 1863 Pissarro showed paintings at the first Salon des Refusés and received laudable mention from the critics. In 1866 and 1868 two of his paintings were admitted to the salon. The young critic Émile Zola took a liking to them and praised them effusively. He particularly emphasized the conscientiousness of the artist Pissarro, who is only committed to the truth. However, these critical successes did not mean any success with buyers and dealers. Pissarro got into financial hardship and had to earn a living painting awnings and roller blinds.

The social and political side of Pissarro is less well known: in his drawings he depicts the living conditions of poor people in realistic forms of expression that are sometimes reminiscent of Daumier . He professed anarchism and dealt with Pierre-Joseph Proudhon .

In 1869 and 1870 he worked closely and regularly with his friends Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir . They often set up their easels next to each other and painted the same motifs together, but each with its own style. In contrast to Monet, Pissarro included people and passers-by much more closely in his paintings: For him, places, landscapes and streets are almost always largely determined by people working, talking to one another or strolling.

In November 1870 he fled the Franco-Prussian War to London after he had previously housed his family in Brittany. He had to leave almost all of his image production behind in Louveciennes near Paris. In London he met Monet again, who had also fled there before the war. The art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel became aware of him and bought four of his paintings from him, but was unsuccessful in reselling them.

On June 14, 1871, Pissarro married his lover Julie Vellay in Croydon, south of London, who was meanwhile pregnant with their third child. He returned to France at the end of that month and learned that some of his pictures had been trampled on by German and French soldiers. They had carpeted them in the garden to keep their boots from getting muddy. Pissarro was not discouraged by this, but worked more productively than ever in the following years. He worked particularly intensively with Paul Cézanne ; both influenced each other very strongly in their artistic development. In financial terms he was confident when his paintings fetched high prices at auction in January 1873, but after that he had hardly any income and was again penniless at the end of the same year.

In 1874 he was one of the driving forces who organized the first Impressionist exhibition. The result of the criticism was disappointing and Pissarro's income from the exhibition was only 130 francs. In the 1870s, Pissarro was struggling desperately for sales and for sheer livelihoods for himself and his family.

Pissarro was a staunch advocate of exchange and collaboration between artists and participated in all other Impressionist exhibitions up to 1882.

The late years

In the mid-1880s he met the young artists Paul Signac and Georges Seurat . He was interested in color theory and adapted its pointillist painting style. He worked with pure, unmixed complementary colors, which he used in ever shorter brushstrokes in order to achieve a mixture of the pure colors to create an overall harmony. In 1886 he exhibited together with Signac, Seurat and his son Lucien in a separate room at the Independent Exhibition. Despite favorable reviews, he failed to make a breakthrough among buyers.

Over time he also felt constrained by the procedural rules of pointillism. While in April 1887 he described himself as an adept of the new art in a letter to Signac, in July of the same year he complained that it was too time-consuming for him. Around 1890 Pissarro turned back to "his" original, freer Impressionism.

In 1892 he finally achieved his breakthrough: with a major retrospective at his sponsor, the art dealer Durand-Ruel. In the last ten years of his life he painted a series of cityscapes from Rouen , Dieppe and Paris. When he died in 1903, he left a huge number of pictures. Since 1980 there has been a Musée Camille Pissarro in Pontoise .

Pissarro's interest in anarchism

In the 1880s, Pissarro met Paul Signac and Georges Seurat . Like many neo-impressionists, he also dealt with the ideas of anarchism . He developed personal acquaintances with Émile Pouget , Louise Michel and Jean Grave . After the attack by Caserio , Pissarro was wanted by the police.

He fled to Belgium, where he met Élisée Reclus and Henry van de Velde . Pissarro had met van de Velde in Belgium in 1894. In March 1897 he wrote a letter to van de Velde in which he described his conversion to Neo-Impressionism and his departure from this painterly method.

After his return to France he published nouveaux in Les Temps and was active against anti-Semitism during the Dreyfus affair .

In 1889 he joined the debating club Club de l'Art Social and subscribed to anarchist newspapers such as Le Père Peinard , Le Révolté , Le Prolétaire , Les Temps nouveaux , in which his illustrations were also published. He also supported the newspapers financially and helped the families of persecuted or imprisoned anarchists. In his cycle of pen drawings, Turpitudes sociales (Social Disgrace), Pissarro expressed his contempt for the exploitation of workers and for Paris society.

Pissarro and the Dreyfus Affair

Pissarro's interest in the political and social consequences of the Dreyfus Affair was the central theme of numerous letters to his son Lucien. On November 19, 1898 he wrote: “ Yesterday, when I went to Durand-Ruel's, at five o'clock, I ran into a horde of high school students on the boulevards, behind whom street boys were running, and they were shouting:“ Death to the Jews! Down with Zola! ”I walked right through the group to Rue Laffitte. They didn't even think I was a Jew. Protests against the Dreyfus judgment are hailing from all sides. The whole intelligentsia protests; and the socialists hold meetings. “The division of his circle of colleagues and some close friends in the aftermath of the Dreyfus affair affected him deeply. Above all, he was tormented by the falling out with Edgar Degas , with whom he had been close friends. Pissarro, Monet, Signac and Vallotton and particularly vehemently the poet and critic Émile Zola (“ J'Accuse ...!”) Supported Dreyfus. On the opposing side were Degas, Cézanne, Renoir and Armand Guillaumin . Anti-Jewish protests broke out across the country and Zola was charged with defamation and convicted. The only way he could escape his imprisonment was to flee to England.

In the course of the Dreyfus affair, Pissarro left France again in 1894 and went to Belgium, but later returned to Paris.

Works (selection)

The catalog raisonné was published in Paris in 1939, listing 1316 oil paintings and several hundred other works. In 2005 the Wildenstein Institute published a new, more comprehensive catalog raisonné with 1528 oil paintings, all from 1939 and adding new discoveries and new insights into the genesis of the artist.

- Portrait of a boy , 1852/55, Ordupgaard Art Museum, Copenhagen

- Two women at the seaside deep in conversation, St. Thomas , 1856, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

- A place in La Roche-Guyon , 1867, National Gallery Berlin

- View from Louveciennes, 1869–1870, National Gallery, London

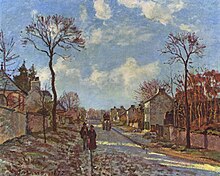

- Street in Sydenham, 1871, National Gallery of Art, London

- The Crystal Palace, London , Art Institute of Chicago

- Portrait of Paul Cézanne, 1874, National Gallery, London

- Jeanne-Rachel Pissarro, 1873–1874, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

- Madame Pissarro sewing at the window, 1873–1874, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

- Boats at Pointoise, 1876, Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

- The Lumberjack, 1878, Musée d'Orsay

- Washerwoman, 1880, Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

- The Little Country Maid, 1882, National Gallery, London

- Study of a peasant girl digging up , 1882, private property

- La Charcutière , 1883, Tate Gallery, London

- Cowherdess, Éragny , 1887, private property

- Poplars, Éragny , 1895, Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

- Steamboats in Rouen, 1896, Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

- Boulevard Montmartre on a winter morning , 1897, Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

- Boulevard Montmartre at Night, 1897, National Gallery, London

- Rue de l'Épicerie in Rouen, in sunlight , 1898, Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

- The Tuileries on a Winter Afternoon, 1899, Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

- The Gardener, 1899, State Gallery Stuttgart

- The Louvre under Snow, 1902, National Gallery, London

- Le Quai Malaquais et l'Institut , 1903, private property

- Le Pont de la Clef à Bruges, Belgique , 1903, Manchester Art Gallery

Up to 19 million pounds sterling are paid for the artist's works today .

literature

Catalog raisonné

- Joachim Pissarro , Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts: “ Pissarro: Critical Catalog of Paintings . “ Wildenstein Institute (Ed.), 3rd volume, Milan 2005, ISBN 978-2908063141 .

Representations

- Christoph Becker, Wolf Eiermann: Camille Pissarro . Hatje Cantz, 1999, ISBN 3-7757-0855-3

- Bruce Bernard (Ed.): The Great Impressionists. Revolution in painting. Delphin-Verlag, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-7735-5323-4

- Richard R. Brettell: Pissarro and Pontoise - the painter in a landscape . Yale Univ. Press, 1990, ISBN 0-300-04336-8

- Richard R. Brettell: Pissarro's people . Prestel, 2011, ISBN 3-7913-5118-4 .

- Raymond Cogniat: Pissarro. Südwest-Verlag, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-517-00650-5

- Gerhard Finckh (Ed.): Camille Pissarro. The father of impressionism (exhibition catalog). From the Heydt Museum Wuppertal, 2014, ISBN 978-3-89202-091-2 .

- Karen Levitov, Richard Shiff: Camille Pissarro: Impressions of City & Country . Yale Univ. Press, 2007, ISBN 0-300-12479-1

- Christopher Lloyd: Pissarro . (Color Library), Phaidon, ISBN 0-7148-2729-0

- Camille Pissarro: letters. Henschel, Berlin 1965

- Joachim Pissarro: Camille Pissarro . Hirmer, 1993, ISBN 3-7757-0855-3

- Katharina Rothkopf: Pissarro - creating the impressionist landscape . Philip Wilson, 2007, ISBN 0-85667-630-6

- Richard Thomson: Camille Pissarro - Impressionism, landscape and rural labor . Exhibition catalog, Amsterdam Books, 1990, ISBN 0-941533-90-5

Web links

- Literature by and about Camille Pissarro in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Camille Pissarro at Zeno.org .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Henry van de Velde: Pissaro and van de Velde, pp. 124–126. Retrieved April 18, 2020 .

- ^ Sylvie Gonzales, Bertrand Tillier, Des cheminées dans la plaine: Cent ans d'industrie à Saint-Denis, 1830–1930 , Créaphis, 1998, texte intégral .

- ↑ L'ephemeris anarchiste : notice biographique .

- ↑ Finckh, Gerhard (ed.): Camille Pissarro. The father of impressionism. From Heydt-Museum Wuppertal, 2014, p. 313.

- ↑ Erpel, Fritz (ed.): Camille Pissarro. Letters. Munich: Rogner & Bernhard, 1970, p. 178.

- ↑ Finckh, Gerhard (ed.): Camille Pissarro. The father of impressionism. From the Heydt Museum Wuppertal, 2014, p. 12.

- ↑ Jürgen Gerhardt: Camille Pissarro as a footnote? For God's sake. No! In: en-mosaik.de from November 1, 2014 → online

- ^ Biography of Camille Pissarro. In: whoswho.de → online

- ↑ Georges Waser: World record for Juan Gris and Pissarro. nzz.ch, February 6, 2014, accessed on February 6, 2014

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pissarro, Camille |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pissarro, Jacob Abraham Camille (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Impressionist painter and pioneer of Neo-Impressionism |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 10, 1830 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Charlotte Amalie (City) |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 13, 1903 |

| Place of death | Paris |