Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas , bourgeois Hilaire Germain Edgar de Gas (born July 19, 1834 in Paris , † September 27, 1917 ibid), was a French painter and sculptor . He is often counted among the impressionists with whom he exhibited together. However, his paintings differ from those of Impressionism, among other things, in the exact lines and the clearly structured composition . On the one hand Degas created numerous portraits , on the other hand he concentrated on a few pictorial themes that he varied again and again: ballet, jockeys and horses, the Parisian nightlife and women in personal hygiene. He devoted himself to oil painting and graphic techniques as well as pastel painting , in which he achieved extraordinary mastery. His sculptures show a new conception of sculpture .

Life

Edgar Degas (for which he was later to 'civil' his name) was born on July 19, 1834, the first of the five children of Auguste de Gas (around 1795–1874) and his wife Célestine Musson (1815–1847) in Paris. The father, a native of Neapolitan , managed the Paris branch of the family's own bank in Naples. The mother was of Creole descent and was from New Orleans ; she died when the son was 13 years old. Degas grew up in a middle-class environment that was open to the arts. After attending the Collège Louis-Le-Grand , he began to study law at the request of his father , which he soon gave up to pursue a career as an artist. His father supported him, among other things, by providing him with a suitable studio. From 1853 Degas took lessons from Ingres' student Louis Lamothe. In 1855 he attended the École des Beaux-Arts for a short time . After that he preferred to continue his artistic training on his own. In the Paris museums he drew from antique reliefs as well as from the models of old masters.

In 1856 Degas set out on the study trip to Italy that was customary for visual artists at the time. He first visited relatives in Naples and then spent around a year and a half in Rome , where he was busy drawing. In July 1858 he continued his journey to Florence ; here he lived again with relatives, the Bellelli family. He made numerous studies of the relatives, which should serve as the basis for a planned group picture.

In April 1859 Degas returned to Paris. He now considered his studies to be over and himself able to master more demanding projects. He demonstrated his skills with the large-format group portrait of The Bellelli Family . Even if the young artist saw himself primarily as a portraitist, he still considered it essential to prove himself in the field of history painting, which was at the top of the hierarchy of pictorial genres at the time. By 1865 he had created five history paintings; one of them, the medieval battle scene , he exhibited in the Salon in 1865 , where it met with little response from the public or critics. This, as well as the doubts he had previously had about the value of history painting, prompted him to concentrate from now on entirely on topics of contemporary Parisian life. His more experienced colleague Édouard Manet , whom he had met years earlier while copying together in the Louvre, was helpful to him . In addition, he came into contact with other modern artists and writers such as Paul Cézanne , Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Émile Zola . The acquaintance with the writer and art critic Edmond Duranty was of particular importance for his further artistic development . From 1866 to 1870 he continued to exhibit in the salon every year.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 Degas served as an artilleryman in Paris; the first complaints about his eye disease have come down to us from this time. He spent the weeks of the bloody Paris Commune with friends in the country.

In 1872/73 the painter traveled to New Orleans, where his numerous relatives on his mother's side lived. Two brothers had meanwhile also settled there; Members of the family were in the cotton business. During the five-month stay a number of portraits of the relatives were created, including the painting The Cotton Office in New Orleans . The next year the father died. As a result, it became apparent that the Paris bank had only been kept afloat by loans and that Degas' brother René had also accumulated high business debts. The bank was wound up two years later, and Degas felt obliged to pay his brother's debts. He had to sell parts of his art collection and restrict his lifestyle. However, his financial situation improved again in later years, as his works recorded immense price increases. This was also due to the support of his art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel .

In 1874 Degas and a group of progressive artists organized the first of a series of exhibitions that would later become known as the 'Impressionist Exhibitions'. They were created with the intention of breaking the exhibition monopoly of the established "salon". Degas took part in all eight exhibitions that took place up to 1886, with one exception. He did a lot for the preparation and organization, but on the other hand caused all sorts of tensions and arguments with his uncompromising attitude and his lack of understanding for the concerns of the other participants.

In the 1890s Degas developed into an avid photographer; preferably he portrayed people from his environment. He exhibited the results in 1895.

Degas remained unmarried. Nothing is known about relationships with women, which gave rise to various rumors among contemporaries. In his later years, his often gruff and malicious manner, combined with his own sensitivity, made friends turn away from him. Degas was a violent anti-Semite . In the Dreyfus affair , which polarized the nation from 1894 onwards, he took sides against the accused Jewish officer, which cost him many friendships, including those with his painter colleague Camille Pissarro . The events surrounding the affair also caused him to break up with particularly close friends, a family of Jewish origin. He made new friends with fellow painters and their families such as Georges Jeanniot and Louis Braquaval . He met Braquaval around 1896 in Saint-Valery-sur-Somme , where Degas also painted a few later landscapes in oil.

The painter's eyesight deteriorated over the years. As a result, he was eventually forced to stop oil painting. Degas made his last pastels and drawings around 1908, but continued to work on sculptures for some time. He spent the last years of his life, lonely and almost blind, in the care of a niece. Edgar Degas died of a cerebral haemorrhage on September 27, 1917.

plant

painting

subjects

A genre that accompanied Degas throughout his life was the portrait . He rarely took portraits, but preferred family members or people he knew as models; he kept the paintings mostly in his possession. He was thus free from external requirements. Degas' portraits are characterized by a high level of psychological observation and representation. His depictions of families and couples often show "discrete breaks in which alienation is heralded". With a few exceptions, the portrayed are not depicted in front of a neutral background, but in an environment appropriate to them.

In the 1860s Degas created five large-format history paintings ; History painting was considered the genre with which an artist could earn the highest recognition. All five paintings are about women: The daughter of Jephthas (1861–1864), Semiramis, contemplating the Babylon she built (1860–1862), Medieval war scene , (1861–1865), Young Spartan women challenge young people (approx. 1860–1862 ) and Mademoiselle Eugénie Fiocre in the ballet 'The Source' (1866–1868). But the painter realized that history painting did not meet his real goals; the figures in these paintings already look contemporary with their individual facial features. Finally Degas gave up the historical subject and concentrated entirely on contemporary issues.

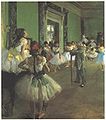

From now on his models were the people, especially the women, of modern, metropolitan Paris. On the one hand, these were the members of his own bourgeois social class and the places where they could spend their free time: racing arena, museum, theater and concert. On the other hand, he liked to portray women from the opposite end of the social ladder: laundresses and ironers, cleaning women, prostitutes. This interest in social reality prompts the art scholar Werner Hofmann to assign Degas' work to realism . One of Degas' great themes, and one that was also preferred by collectors, became the dancer. Of the well over 200 works on the subject of ballet, only a little more than a fifth deal with the actual performance, the rest shows the almost always nameless dancers behind the scenes at Degas, at rehearsals or while resting. The ballet as the focus of the motif, with an almost exclusive interest in the representation of the individual dance (s) itself, in the individual ballet works and in the specific prominent dance artists, is only found later with Ernst Oppler, who is around 30 years younger .

At the center of Degas' late work is a series of pictures, mainly pastels, female nudes that bathe, wash, dry off, comb or do their hair. The painter refrained from showing an ideal image of the female body, as it had become a convention in academic painting. Instead, he portrayed women in natural form and natural poses. He himself said: “Until now, the naked has always been portrayed in poses that require an audience, but these women of mine are respectable, simple human children who have no other interests than those who are based on their physical condition ... It is like looking through a keyhole. "

Stylistic features

Degas' early portraits show the classicistic style of his role model Ingres . Take, for example, the portrait of René Hilaire Degas from 1857. When the painter turned to the motifs of city life towards the end of the 1850s, his formal goals also changed. He was now primarily looking for new, exciting spatial solutions. The attention he devoted to the division of the picture surface and the precise delimitation of the forms set him apart from the impressionists to whom he is often assigned.

Place de la Concorde (around 1875), oil on canvas, 79 × 118 cm ( Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic and his two daughters)

Characteristic of Degas' paintings are decentralized compositions that move the actual events to the edge of the picture. This creates a tension between the abundance of an empty space and the other, for example in the pictures Die Tanzklasse (around 1871), Place de la Concorde (around 1875) and Dancers on the Pole (1876/77). Often figures are apparently arbitrarily cropped or cut up. This happens either through the edge of the picture, as in Place de la Concorde , where all four people and the dog can only be seen in fragments, or through objects placed in front, as in the painting At the Milliner (1882), where the standing mirror not only cuts up the room , but also dismembered the milliner's body. Both stylistic devices process influences from developing photography as well as Japanese prints, which were very popular among European painters at the time . They give the paintings the appearance of snapshots .

The influence of Japanese art also reflects Degas' tendency to flatten the pictorial space by foregoing perspective means . Sometimes floors, as in Die Grüne Tanzinnen (1877–1879), are projected less into the depths than into the surface, so that “[…] one thinks that they would slide into the bottomlessness, hardly giving the bodies any more support.” A flat effect the painter also achieved by drawing the foreground and background together, skipping the middle ground. In the painting Musicians in the Opera (1872) the distance between the musicians and the dancers on the stage is canceled. This also leads to extremely disparate proportions of the figures shown.

Degas' joy in experimenting led him to look for unusual angles, such as Miss Lala in the Fernando Circus (1879), who was seen from below .

Pastel painting

At the beginning of the 1870s Degas discovered pastel painting for himself and brought it to perfection in a creative process that lasted over three decades. His pastel paintings were admired by contemporary artists. He developed a special technique for his painterly elaborated pastels. The pictures were built up in numerous layers, with each new layer of color being fixed. To do this, Degas used a special fixative whose recipe he had brought back from Rome. With his process, he achieved a bright color and a dry color effect that was reminiscent of fresco paintings . Degas' pastels became a model for many subsequent artists.

Working method

Degas rejected the open-air painting popularly practiced by the Impressionists . He worked in the studio with the help of models or drawings that he had made on site or taken from an already existing fund. “There has never been an art that is less spontaneous than mine,” he explained. “What I do is the result of thinking and studying the great masters. I don't know anything about inspiration, spontaneity, temperament […]. ” In the years 1895/96 Degas occupied himself with photography; Two paintings from this period are documented, for the preparation of which he used his own photographs. However, since the process apparently did not satisfy him, he then returned to drawing. Degas attached great importance to drawing and painting from memory because of the associated release of the imagination.

There is a tradition of the artist's habit of reworking finished pictures over and over again.

drawing

Degas drew throughout his fifty years of creativity until he had to give up this artistic discipline around 1908 because of his bad eyesight. Numerous statements have come down to us that make it clear what importance he attached to drawing and that he valued his drawings more than his paintings.

The artist's willingness to experiment is evident in the choice of his means of representation. He drew with pencil , chalk, charcoal , pastel pencils and thinned oil paint on partly colored tinted paper, often combining different techniques on one and the same sheet. Degas had a particular fondness for colored drawings; for this, pastel chalk became his preferred medium from the beginning of the 1870s. It allowed him to combine a linear, graphic representation with painterly flatness. Many of his pastels are so strongly illustrated that the demarcation from painting becomes blurred.

During his student years from 1853 to the end of the 1850s, Degas used drawing primarily to acquire the knowledge and methods of older models. He made over 740 traces, mostly after masters of the Renaissance and Classicism . He concentrated on figurative representations. In this phase his drawing style shows a growing sense of security and spontaneity.

After that, Degas used the drawing on the one hand to prepare paintings, on the other hand he increasingly made drawings that were intended as an 'end use'. From the 1880s onwards, drawing outpaced painting production. The late work is characterized by larger formats (due to the deteriorating eyesight) as well as a progressive coarsening and the renunciation of spatial illusion.

Printmaking

Degas' enthusiasm for experimentation and his interest in new techniques are particularly evident in the field of printmaking. He created numerous etchings , using drypoint as well as etching and aquatint and mixing these processes with one another. He also experimented with lithography . He became known for his monotypes . Using this printing technique, only one clear and at most one or two weaker prints can be made, which Degas often reworked with pastel chalk. The mostly small-format monotypes show scenes from ballet, theater and everyday life in the brothel.

Sculptures

After Degas' death, more than 150 sculptures were found in his studio, most of them in poor condition. Only one of them, the fourteen-year- old dancer , who finished in 1878, was exhibited to the public in 1881. The rest of the horses, dancers and bathers are dated to Degas' later years. Presumably, after the deteriorating eyesight had made painting impossible, he concentrated entirely on three-dimensional work. Most experts no longer share the earlier view that they served as models for paintings. Degas used different materials such as wax, clay, plasticine and textiles for the sculptures . This and the resulting multicolor were alien to traditional sculpture.

The fourteen-year-old dancer was exhibited by Degas at the sixth impressionist exhibition in 1881. The wax figure with realistic facial features, equipped with a real skirt and dance shoes made of fabric, a linen bodice, a headband made of satin and horsehair was outside the established sculpture of the 19th century. She was judged differently by critics. While some condemned its “terrible reality”, felt it to be “ugly” or “wretched”, others like the writer Joris-Karl Huysmans saw it as a future-oriented conception of sculpture: “[...] all the public's ideas about sculpture, about it cold, lifeless, white apparitions, over these memorable stencil-like works repeated for centuries, are overturned. The fact is that Monsieur Degas overturned the tradition of sculpture [...]. "

Posthumously, Degas' heirs had 72 of the sculptures bronze casts made in sometimes very large editions.

Degas as a collector

Degas built up an important art collection largely in secret. In his estate there were over 1,000 paintings and drawings as well as 4,000 prints, among others by Ingres , Delacroix , Daumier , but also by contemporaries such as Édouard Manet , Paul Cézanne , Paul Gauguin and Mary Cassatt . Degas acquired the majority of these works in the 1890s. There were also numerous paintings, drawings and prints by his own hand.

In the two years after his death, Degas' heirs had the approximately 8,000 objects auctioned. The buyers included the Musée du Louvre in Paris, as well as the National Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

reception

Degas was held in high regard by his artist colleagues. Camille Pissarro wrote to his son in 1883: "Degas is certainly the greatest artist of our time." Later he emphasized the modernity of Degas, who "[...] continuously advances and finds peculiarities in everything that surrounds us." In his successor stood above all Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and his friend Walter Sickert . Later artists, including Pablo Picasso , found inspiration in Degas.

His work also attracted the interest of collectors early on, including the painter and collector Gustave Caillebotte and the American collector Louisine W. Havemeyer, who was personally known through Degas . With the cotton office , the museum in Pau was the first museum to buy a work by Degas in 1878. From the 1880s onwards, his pictures increased in value, "[...] reminiscent of speculation on the stock market." In 1912, Mrs. Havemeyer bought the painting Dancers on the Pole from 1877 for 435,000 francs. (For comparison: In the same year Degas was offered the purchase of a Paris town house for 300,000 francs.) With the estate of Caillebotte, the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris took over a series of Degas' pastels in 1896 (now in the Musée d'Orsay ). After the death of Louisine W. Havemeyer after 1929, a large number of his paintings were donated to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art .

In 2008, a mixed media piece of paper called Dancers on the Pole at Christie's , London, achieved more than 17 million euros. The bronze cast of Degas' Petite danseuse de 14 ans ("Little fourteen-year-old dancer") from 1922 (original around 1880) went to one in February 2009 via the London auction house Sotheby’s for 13.26 million pounds (14.4 million euros) Asian collector.

Important Degas collections are in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Eponyms

- In 1979 a Mercury crater was named after him.

- In 1986 the image processing program DEGAS was named after him.

- In 1996 the asteroid (6673) Degas was named after him.

- In 1997 a rose variety was named Edgar Degas .

Exhibitions

- Degas: Classics and Experiment , Kunsthalle Karlsruhe , Karlsruhe. Catalog.

- 2016/17: Degas & Rodin . Giants of Modernity , Von der Heydt Museum , Wuppertal

literature

- Paul-André Lemoisne : Degas et son oeuvre . P. Brame et CM de Hauke, Paris 1946-1949, OCLC 977103837 (French).

- Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings . DuMont, Cologne 1984, ISBN 3-7701-1552-X .

- Denys Sutton: Edgar Degas . Hirmer, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-7774-4270-4 .

- Richard Kendall (Ed.): Edgar Degas. Life and work in pictures. Delphin, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7735-5389-7 .

- Wilhelm Schmid (ed.): Ways to Edgar Degas. Matthes & Seitz Verlag, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-88221-236-5 .

- Marion Vogt: Between ornament and nature: Edgar Degas as a painter and photographer (= studies on art history , volume 134), Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York, NY 2000, ISBN 3-487-11082-2 (dissertation University of Saarbrücken 1996, 251 pages, illustrated, 21 cm).

- Angela Wenzel: Edgar Degas, Magic of the Dance Prestel, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7913-2731-3 .

- Bernd Growe: Edgar Degas. Taschen, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-8365-4339-7 .

- Werner Hofmann: Degas and his century . Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-56497-0 .

- Ambroise Vollard: Memories of Edgar Degas . Piet Meyer, Bern / Zurich 2012, ISBN 978-3-905799-20-0 .

- Jonas Beyer: Between drawing and printing: Edgar Degas and the rediscovery of the monotype in the 19th century , Fink, Paderborn 2014, ISBN 978-3-7705-5568-0 (Dissertation Freie Universität Berlin 2012, 406 pages, illustrated, 24 pages) .

- Christian Berger: Repetition and experiment with Edgar Degas , Reimer, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-496-01498-0 (Dissertation Freie Universität Berlin 2013, 215 pages, illustrated, 24 cm).

- Miguel Orozco Degas Monotypes: A Catalog raisonné 2019 , Academia.edu

Movie

- David Thompson and Ann Turner: The unquiet spirit of Edgar Degas . Documentation 65 min., Arthaus Musik, 2008, ISBN 978-3-939873-11-2 .

- Nelson Castro: Degas . 21min. France 2013

Web links

- Literature by and about Edgar Degas in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Edgar Degas in the German Digital Library

- Works by Edgar Degas at Zeno.org .

- Janca Imwolde: Edgar Degas. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Edgar Degas on kunstaspekte.de

- Edgar Degas at Google Arts & Culture

- Degas' family tree illustrated with paintings at geneanet.org

Individual evidence

- ↑ gw.geneanet.org: H Laurent Pierre Augustin de GAS

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 26.

- ↑ Denys Sutton: Edgar Degas. P. 310.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann: Degas and his century. P. 49.

- ↑ Denys Sutton: Edgar Degas. P. 102ff.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann: Degas and his century. P. 316.

- ↑ Denys Sutton: Edgar Degas. Pp. 227/228.

- ↑ Denys Sutton: Edgar Degas. P. 301 ff.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988 ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) - exhibition catalog: Edgar Degas. Pp. 566-567.

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 100.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann: Degas and his century. P. 316.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann: Degas and his century. P. 40.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann: Degas and his century. P. 9ff.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann: Degas and his century. P. 170.

- ^ Ernst Oppler exhibition 2017

- ↑ Quoted from: Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas: Pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 89.

- ↑ Werner Hofmann: Degas and his century. P. 150.

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 84.

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas: pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 50/51.

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas: pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 67.

- ↑ Quoted from: Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 60.

- ↑ Three Photographs ( Memento of July 8, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Edgar Degas to be Featured in Exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum . Text for an exhibition at the Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. Footnote 184 to p. 67.

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 18.

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 32.

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 34.

- ↑ Angela Schneider, Anke Daemgen, Gary Tinterow (eds.): French masterpieces of the 19th century from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York ( exhibition catalog ), p. 141.

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 80.

- ↑ Angela Schneider, Anke Daemgen, Gary Tinterow (eds.): French masterpieces of the 19th century from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. P. 140.

- ↑ Quoted from: Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 82.

- ^ The Private Collection of Edgar Degas Website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York ( Memento June 6, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Denys Sutton: Edgar Degas. P. 308.

- ↑ Quoted from: Werner Hofmann: Degas and his century. P. 9.

- ↑ Quoted from: Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 12.

- ^ Götz Adriani: Edgar Degas - pastels, oil sketches, drawings. P. 12.

- ↑ Denys Sutton: Edgar Degas. P. 295.

- ↑ Proof of the painting in the Metropolitan Museum's online inventory catalog.

- ↑ Denys Sutton: Edgar Degas. P. 307.

- ^ Christie's website.

- ↑ Almost 15 million euros for a 14-year-old . In: The world . February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Edgar Degas in the Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature of the IAU (WGPSN) / USGS

- ↑ Computer Magazine Archives - Classic Computer Magazines. Retrieved September 29, 2017 .

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 26932

- ↑ Nelson Castro: Degas. Retrieved September 29, 2017 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Degas, Edgar |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | de Gas, Hilaire Germain (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French painter and sculptor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 19, 1834 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 27, 1917 |

| Place of death | Paris |