House of Eternity (Ancient Egypt)

| House of Eternity in hieroglyphics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old empire |

Per-djet Pr-ḏ.t House of Eternal Time / House of Eternity |

||||

| Greek | Aidioi oikoi Eternal Houses |

||||

| Pyramids of Giza | |||||

In ancient Egypt , the term called " House of Eternity " a grave plant , the first mostly as pit grave shaft or adobe was and later from rock hewn or built in an open area. Due to their long durability as a "symbol of immortality", grave structures made of stone represented the "ideal design", which, however, only very few ancient Egyptians could afford due to the high costs. The monumental grave laid out in this way during his lifetime represented the most intense form of connection between life and the idea of survival in the hereafter in ancient Egyptian mythology .

For the owner of the grave, the “House of Eternity” was a “place of encounter with oneself”, the decorations a reflection of the stations in his life. He immortalized his “doppelganger” on the grave walls and awakened him to “new life in later times” with inscriptions . In the “House of Eternity” the grave owner showed his “perfect life” in anticipation of death, which according to his belief should be withdrawn from oblivion and transience in this form of representation.

The grave owner hoped to meet his ka in the afterlife through an impeccable way of life . The "House of Eternity" was the place that enabled the grave owner to remain unchanged in "eternal time" ( djet ). Against this background, the ancient Egyptians celebrated the “ Celebrations in the House of Eternity ” every year on important occasions .

Mythological connections

According to ancient Egyptian ideas, life in this world was short-lived compared to eternity . The Egyptians therefore used two terms of time for "Eternal cycle of life on earth" ( neheh - nḥḥ) and "Life in the eternity of the realm of the dead" ( djet - ḏt ). “Neheh” stands for the period in which something exists, renews and repeats itself. “Djet” refers to the future in which “earthly life will have been” and everything “perfect in life dwells in the duat for an indefinite period ”.

The sun god Re was seen as a manifestation of the “neheh time”, since Re “renewed himself every night” and with the daily sunrise is “reborn” again and again by the sky goddess Nut . As the god of the dead , on the other hand , Osiris was a synonym for the “djet time”, which in its appearance as a mummy also bore the nickname “the one who lived in perfection” in this context. In this respect, neheh is the Re-time of renewal and djet the Osiris-time of remembrance.

The "life goal" of the ancient Egyptian represented the eternal continuation in the "kingdom of Osiris", for which the deceased required embalming and mummification and the approval of the judgment of the dead . A previously lived life in moral perfection symbolized “the good”, which after “examination by the judgment of the dead” was allowed to pass into the afterlife and, associated with it, into the “djet time”. The "House of Eternity" also functioned as a "court of justice and mummification hall", which was constructed according to the principles of the goddess Maat .

The "House of Eternity" as the "Book of Life"

The ancient Egyptians lived life from birth with a view of later death. With the entry into “working life”, the planning for their own “house of eternity” began for the high-earning officials or for those working in the temple cult. The income was used to create reserves that were used for the gradual expansion of the grave complex. After the “ laying of the foundation stone ”, the inscriptions in the grave that reported the “stages of life” followed. The tradition of the ancient Egyptian "House of Eternity" had its roots in " result-oriented thinking", which was based on the past culture and provided no room for innovations on a religious level.

In contrast to “ spiritually innovative progress ”, which takes into account the experiences of life and continually adapts to new circumstances in the further course, the Egyptian saw personal life up to death as the perfect result of preparation for the hereafter, in which “the on Repeat the actions taken “. The "actions to be repeated" had their spiritual foundation in the cult of the dead , which "prescribed to the living how a morally impeccable life should look like". In return for the “successful accomplishment of the tasks in life”, the “crossing to the holy land ” beckoned as a reward after death . The starting point for that transition into the Duat was the “House of Eternity”. This made the construction and alignment of the tomb the most important project in the life of an ancient Egyptian.

The "House of Eternity" contained the hope of immortality after death. In this context, the grave owner repeatedly asked himself worriedly whether he was leading a glorious life. For him, the grave had the function of a mirror, which showed the grave owner his life in the "light of what it was".

There was a close connection between the "House of Eternity" and the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing . The arrangement of the interior of a tomb followed a fixed construction for thousands of years. The hieroglyphic script was primarily linked to the "House of Eternity" and was therefore only subject to minor changes in its appearance. Just as the “house of eternity” was to remain immortal, hieroglyphic writing also followed this principle. Even the educated "ancient Egyptians of the 25th dynasty " should still be able to read and understand the grave reports of "his ancestors of the 1st dynasty ".

According to ancient Egyptian understanding, the “House of Eternity” also functioned as a “Book of Life” that the grave owner wrote in his role as author . The grave complex and the hieroglyphic writing together formed a “ work of art ” that was passed on from generation to generation as a template for the later “Houses of Eternity”. The hieroglyphic writing and the "House of Eternity" were based on the "Foundation of Cultural Memory". Old systems were sanctified, which prevented an alienation from one's own grave culture. The maintenance of old traditions cannot be equated with "inability to develop further", but is an expression of the "ancient Egyptian longing for immortality". In a wisdom book of the 19th dynasty it is written:

“They passed away and completed their lifetimes, all of their contemporaries were forgotten… But they created books as heirs and teachings that they wrote… They made gates and chapels; they fell apart. Their priests of the dead have gone away, their altars are polluted ... and their names would have been forgotten, but it is the book that keeps the memory of them alive. "

Celebration in the "House of Eternity"

→ Main article: Celebration in the house of eternity

Celebrations in the "House of Eternity", which were meant for the grave owner among his relatives and friends, are already represented in the Old Kingdom. The associated cult of the dead was fully developed by the 5th dynasty . At the most important festivals of the year, special offerings and consecration offerings were brought to the "House of Eternity". At this time the focus was still on the “feast for the grave owner and for various deities”, which was then followed by music and dance. The collapse of the Old Kingdom was connected with a religious addition to the cult of the dead in the Middle Kingdom . With the addition of the duat , the new three-level view of the world was created, which was fixed in writing with the "access to the beyond of heaven and the duat" through dissemination also in the non-royal cult of the dead, among other things in the newly emerging coffin texts .

With the introduction of the Book of the Dead in the New Kingdom, the "earlier supper for the upper class" achieved a broader audience. Particularly noteworthy is the valley festival , which in the course of the 18th dynasty developed into an exuberant feast in the “House of Eternity” with dancing and drinking . The focus was no longer on the grave owner embodied as a statue and symbol of later life in the Duat, but mainly as the "recipient of offerings and consecration in life". During the reign of Akhenaten , who introduced the cult of Aton , the celebrations in the "House of Eternity" temporarily ended. With the beginning of the 19th dynasty , the earlier traditional forms were again in the foreground, which replaced the glamor of exuberance during the 18th dynasty with serious content.

"Houses of Eternity"

From the work "History of Egypt" from 320-305 BC Chr in. Alexandria at the beginning of the Ptolemaic acting Greek historian Hecataeus of Abdera , who reported on the lives of the Egyptians, have been preserved only quotes. Above all, the description of the Nile land in the first book of the world history of Diodor is based essentially on Hecataeus. One of his quotes tells about the houses of eternity:

“The locals give very little value to the time spent in life. They call the dwellings of the living " dismount " because we only lived in them for a short time. On the other hand, they place the greatest emphasis on the time after their death, during which one is preserved in the memory by the memory of virtue. They refer to the graves of the deceased as "Eternal Houses" because they spent infinite time in Hades . Accordingly, they spend little thought on equipping their houses, whereas no expense seems too high to them for the graves. "

The observations of Hecataeus of Abdera corresponded to the actual conditions in ancient Egypt. The houses of the Egyptians as well as the royal palaces were made of air-dried clay bricks , which were the simplest and cheapest building material. On the other hand, the "houses of eternity" built like temples were, if possible, made from stone blocks or as rock tombs .

Mastabas

The mastaba is a type of tomb named after the Egyptian-Arabic word for bank. In terms of art history, mastabas can be assigned to a line of development that began with elite graves from the early dynastic period , led to the construction of pyramid tombs in the royal area and did not end in the private sector until the end of the 12th dynasty .

The burial took place below the actual building, in a chamber at the end of a shaft. In comparison, the mastabas of the lower courtiers are usually rather simple and do not have a niche facade. At the end of the Old Kingdom , the classic mastaba shape dissolves. The decoration is now mostly reduced to a false door , while the burial chamber is decorated more and more often.

Pyramids

The pyramids represent a further development of the mythological " original hill " that can be found at royal tombs in Abydos . The hill structure was also incorporated into the mastaba tombs of Saqqara . From the 3rd dynasty , the pyramids served as the king's burial place, which developed as a synthesis of the various Upper and Lower Egyptian components of tombs and valley districts. Elements of the graves and grounds can be found in Saqqara. The large enclosure in Saqqara ( Gisr el-Mudir ), as a stone equation of the valley districts of Abydos, may have served as a model for the enclosure of the pyramid district, as did the gallery graves of the 2nd dynasty in Saqqara.

The construction of the Djoser pyramid created a new visual appearance for the "House of Eternity", which was supposed to enable the deceased king to take on a rank equivalent to the sun as the "human equivalent of the sun ( Goldhorus )". This new royal philosophy was also reflected in the increasing size of the subsequent pyramids. The walls inside these buildings initially had relief decorations on the Djoser pyramid , but were later undecorated until the end of the 5th dynasty . The way to the tombs led through a long tunnel in the pyramids.

Up until the 3rd dynasty, the kings saw themselves as "earthly Horus", but from King Radjedef ( 4th dynasty ) onwards, when the sun rose to the deity Re , they understood themselves as " sons of Re ". The changed "ranking" led to a size reduction of the pyramids. The literary work " The Doctrine of Hordjedef ", which refers to the graves of the Old Kingdom as "Houses of Eternity", is only preserved in a few fragments . Due to its language, the Middle Kingdom can be clearly dated as the time of origin of the work . It starts with the quote:

“Make your house in the west splendid and furnish your seat in the necropolis generously . Accept this, because death is low to us, accept this, because life is high to us. But the house of death serves life. "

The rest of the text deals with the grave complex. According to this, the “house of eternity” ideally includes a piece of land in order to be able to provide the necessary income as offerings . In the Old Kingdom there was the office of “Overseer of the House of Eternity”. A funeral priest took care of the offering of the “proceeds from the house of eternity”: “That will be more useful to you than a biological son. Promote him more than your heir. Think of what you say, because there is no heir who remembers forever ”.

Temple tombs

Temple-like tombs have existed since the Middle Kingdom. They were found in all parts of Egypt and are attested until the late period . Some of the temple tombs had an access road and were surrounded by a wall with pylons at the front . The actual burial chapel had a courtyard, optionally decorated with columns. Behind it was a cult room with a statue or a false door .

The facilities of the Middle Kingdom in Lischt were partly built in a monumental style. In Thebes there were smaller versions made of mud bricks. In the New Kingdom this grave type flourished, especially in Saqqara was a variety of these tombs found and excavated . The walls were often decorated with reliefs, more rarely with paintings. Small pyramids were found as a new feature.

Shaft and rock graves

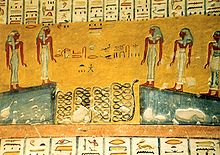

Most ancient Egyptians let themselves be buried in simple shafts or pits for reasons of cost. The tombs of the kings of the New Kingdom ( 19th and 20th dynasties ) are located in the Valley of the Kings . The valley lies in Thebes-West opposite Karnak on the edge of the desert and is lined with high mountains, in particular by the natural rock pyramid el-Qurn ("The Horn"). Almost the entire area of Thebes-West forms a huge necropolis in which 64 graves and other pits have been found to date.

There are three basic types of graves in the Valley of the Queens . The oldest systems are simple, undecorated shaft graves . These usually only had one room, more rarely one or two side chambers. The graves usually consist of two large rooms one behind the other. There were up to five secondary chambers. The graves are usually richly decorated.

None of the systems shows the remains of a superstructure that was normally reserved for the cult of the dead. These are likely to be found on the edge of the fruit and are shaped like small temples. From the time of Thutmose III. comes the text in grave TT 131 of the vizier Amunuser , which expresses the "result-oriented thinking" in a few words:

“I built an excellent tomb in my city of abundance of time ( neheh ). I made excellent use of the location of my rock ditch in the desert of eternity ( djet ). May my name endure on him in the mouths of the living, while the memory of me is good with people after the years to come. This world is only a little of life, but eternity is in the realm of the dead. "

literature

- Jan Assmann : Death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt. Special edition. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49707-1 .

- Ulrike Fritz: Typology of the mastaba's graves of the Old Kingdom. Structural analysis of an ancient Egyptian grave type (= Achet - Schriften zur Ägyptologie. A 5). Achet-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-933684-19-6 (also: Tübingen, Univ., Diss., 2000).

- Siegfried Schott : The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Festive customs of a city of the dead (= Academy of Sciences and Literature. Treatises of the humanities and social science class. Born in 1952, No. 11, ISSN 0002-2977 ). Publishing house of the Academy of Sciences and Literature, Mainz 1953.

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Vol. 30). 3rd, updated and expanded edition. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 .

- Kent R. Weeks (Ed.): In the Valley of the Kings. Of funerary art and the cult of the dead of the Egyptian rulers. Photos by Araldo de Luca. Weltbild, Augsburg 2001, ISBN 3-8289-0586-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt . Pp. 484-485.

- ↑ Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. P. 64 and p. 66.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt . P. 169.

- ↑ Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Pp. 76-77.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt . P. 483.

- ↑ Mark Lehner : The first wonder of the world. The secrets of the Egyptian pyramids. ECON, Düsseldorf et al. 1997, ISBN 3-430-15963-6 , p. 75 ff .: The royal tombs of Abydos.

- ^ W. Helck : History of ancient Egypt (= Handbuch der Orientalistik . Abt. 1, Bd. 1, 3). Photomechanical reprint with corrections and additions. Brill, Leiden 1981, ISBN 90-04-06497-4 , pp. 45-46.

- ^ Günter Burkhard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history. Volume 1: Old and Middle Kingdom (= introduction and source texts for Egyptology. Volume 1). 2nd Edition. LIT, Münster et al. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8258-6132-2 , p. 81.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt . P. 481.

- ↑ Hellmut Brunner : Ancient Egyptian wisdom. Lessons for life (= The library of the old world. Series: Der Alte Orient. Vol. 6). Artemis, Zurich et al. 1988, ISBN 3-7608-3683-6 , p. 103.

- ↑ Eberhard Dziobek: The graves of Vezirs User-Amun Thebes No. 61 and 131 (= Archaeological Publications 84). von Zabern, Mainz 1994, ISBN 3-8053-1495-7 , pp. 78-79.