Tomb of the Night (TT52)

The Tomb of the Night is the private tomb of the ancient Egyptian civil servant Nacht and his wife Taui. The rock tomb, rediscovered in the necropolis of Thebes-West in Egypt in 1889 , is dated to the 18th Dynasty, i.e. to the time at the beginning of the New Kingdom around 1400 BC. It bears the number TT52 (TT = Theban Tomb = Theban grave) of the graves of Sheikh Abd el-Qurna in West Thebes. Several details of the high-quality wall paintings , which are often referred to in Egyptological literature , are particularly well known . Little of the rest of the furnishings in the unfinished grave has survived today. The paintings are now badly damaged, but thanks to the work of the archaeologist Norman de Garis Davies, they are known to have been found.

Discovery and research

Towards the end of the 19th century, probably in 1889, Egyptians from the village of Sheikh Abd el-Qurna (on the west side of the Nile, opposite Luxor ) found the grave and gained access. Shortly afterwards, officials from the Egyptian Antiquities Service under Emile Grébaut carried out the first cleansing operations in the grave. Shortly before that, apparently four small painting fragments were stolen from the grave by a traveler and sold to the USA. They are now in the Brooklyn Museum . The first drawings of the decoration were made by Gaston Maspero and Hippolyte Boussac .

The grave initially remained unknown to a wider public until the British Egyptologist Norman de Garis Davies took up the paintings between 1907 and 1910. His special qualities as an artist helped him. With the help of other archaeologists, including his wife Nina de Garis Davies , he drew all the frescoes in the tomb in painstaking detail . Then in 1917 this work was presented to the public in a magnificent publication. This publication is so valuable today because it shows the frescoes in an undamaged condition. In the last few decades their condition has deteriorated, not least because of the large number of visitors. Ultimately, only closing the tomb to the public could prevent its complete destruction.

In Europe, Davies' works were first presented to a broad public in 1991 as part of the exhibition " Egypt - Search for Immortality " in Hildesheim . They were then shown in Mainz and other cities as a special exhibition on the grave of the night. In the course of this presentation, a color picture book with photographs of all original images of the tomb was published for the first time by the Egyptologists Matthias Seidel and Abdel Ghaffar Shedid .

Grave owner

| Night in hieroglyphics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Night Nḫt The Strong |

|||

The personality of the night - Egyptian for The Strong - can only be determined on the basis of inscriptions and the representations in the grave, as no other finds exist about him so far. Nacht calls himself “Schreiber”, but this term is very imprecise and only identifies him as an official. After all, it follows from this that he belonged to a small senior class of officials in the Reich. A second title is "Priest of the hours of Amun ". In this function he had to monitor the observance and punctual execution of certain cult rituals in the imperial temple of Amun-Re in Karnak . The combination of the two titles, which is sometimes interpreted as "astronomer", shows in its imprecise way that Nacht probably only belonged to the middle class, an assumption that is also supported by the modest furnishings of his grave. His wife Taui, who was the temple singer of Amun, is buried next to him in the tomb. The remains of other coffins have also been found.

Description and inventory

The small rock tomb is located on the ascent to Sheikh Abd el-Qurna's burial hill, the preferred burial site for officials in the area. The tomb consists of two parts, an above-ground cult facility, which was accessible to ancient Egyptian visitors, and the underground part with the burial chamber, which was locked after the burial. Only the part above ground was decorated.

The grave is also built in the usual form of such Theban private graves of the early and middle 18th dynasties: First you enter an open courtyard. After a short passage you come to the so-called “wide hall”. This is about 5 meters wide, 1.5 meters deep and is the only one that is almost completely decorated. Another narrow corridor follows, which is followed by the so-called "deep hall" in the form of a slightly elongated rectangle, which was probably just plastered. There was no painting. On the back wall of the room there is a niche that probably used to house a statue of the tomb owner and his wife. In the floor of the room a wide shaft leads to the undecorated coffin chamber. After the burial, the shaft was filled with rubble and sand and thus made inaccessible. These above-ground rooms remained accessible.

The grave was no longer completely intact when Davies took it. The investigation of the subterranean coffin chamber began without great expectations, but at least brought an important individual find to light. It was a painted stelophore knee figure that shows night. The painting is almost completely preserved. Originally, the 40 centimeter high statue was above the entrance to the tomb complex. It faced east, which was of particular importance in connection with the inscription on the statue. The inscription, from which, as everywhere else in the grave, the name of the god Amun was erased, reads:

Worship Re when he rises

to the onset of his downfall in life

by the hour priest of [Amun]

the night scribe, justified.

Greetings, Re , on your rise,

Atum , on your beautiful fall!

You appear and shine on your mother's back,

you have appeared as the king of the gods.

Nut carries out the njnj greeting in front of your face,

mate hugs you at all times.

You cross the sky with a wide heart,

the knife lake has come to rest.

The rebel has fallen, his arms are tied,

the sea has cut his vortex.

The statue was shipped to New York in 1915 . On the way there, the steamer Arabic was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine. As a result, the statue is probably lost forever. Other grave finds were sparse and mostly fragmented. Parts of several coffins, furniture, clay vessels and some grave cones were recovered. The few and almost completely destroyed finds prove that the grave was looted by grave robbers.

Grave design and image program

In the middle room, on both sides of the entrance, the deceased couple is depicted with burn victims (Fig. 1). On the left side you can also see farmers working in the fields and harvesting (picture 2), on the right side fork bearers (picture 7). On the left narrow side there is a false door (picture 3), on the right there are offerings in front of the owner of the grave (picture 6). The so-called “Beautiful Festival of the Desert Valley” is shown on the left back wall (picture 4), on the right back the hunt in the papyrus thicket, the grape harvest and the catching of birds (picture 5).

Work process and artist

It is noticeable that the paintings are not completely executed. It can be assumed that they were stopped after the death of the night and that the latter thus died while the work on the grave was still in progress. It is particularly striking that the work on the first room is largely complete, while the last room, which led to the burial chamber, was not completed beyond the fine plastering work. Not all internal drawings, structures and contours have even been executed in the painted space.

The limestone from which the grave was made is porous and brittle, which is why it was not possible to smooth the stone surface and use it directly as a painting surface. As a result, several layers of different plastering materials and primers had to be applied in the grave - as with most of the other graves in Thebes. First, a layer of clay and chaff was applied to the rough hewn wall to level it. On top of that was a second layer of plaster and mortar that was supposed to smooth the ground. Finally, a thin layer of plaster was applied as a painting surface. White whitewash was used as the base color. Now there was a uniform shade and a paintable surface that did not have the absorbency of pure plaster.

In the case of larger representations that span several grids, the painter used fine square nets that served as an aid for proportioning. In the case of rather unimportant people such as the victim-bearers, he only sketched an axilla for rough orientation. Straight lines were drawn with the help of a ruler or using a pull cord technique. With the cord pull technique, a rope dipped in color is attached between the two end points of a straight line, tensioned and snapped against the wall. The painter did not sketch out all the details and designed various details freely. After the contours had been drawn, he applied the colored areas. It was not uncommon for him to apply several layers to emphasize individual details. In a final step, he traced the contours again with red-brown paint.

Based on the degree of manufacture of the walls, it can be seen that each work step was apparently carried out one after the other for all pictures, but not always consistently. The usual color pigments were used: Calcite , calcium sulfate and huntite for white, carbon black for black, ocher for yellow, red and brown tones, Egyptian blue (artificially produced pigments with cuprorivaite ) for blue and wollastonite for green. Even with modern research methods, the binding agent can no longer be determined today. The colors made it possible to paint large areas as well as finely sculpted. It is noticeable that the expensive green and blue tones were used generously and are interspersed in all scenes. In the case of the hunting scene, which is unusual, the entire background of the picture was even kept green and a thick stripe symbolizing water was painted on. Also striking are the fine color variations of the blue, green and ocher tones, which were achieved by mixing and diluting. You can see this very nicely in the skin colors of the people, which were usually designed quite individually.

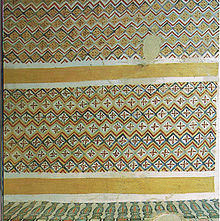

At the bottom of the walls is a plinth that has been whitewashed. Usually, however, it should have been black. The base and the pictures were separated from each other by a red and yellow colored strip. In the grave of the night, however, they were only completed on the right back wall. On the sides and at the top, so-called color conductors - ribbons with black borders in the color sequence green, ocher, blue and red with small white stripes in between - form the ends of the picture. Where two walls meet, vertical colored conductors with a black and white braided pattern formed the connection. The upper end of the walls was formed by the so-called cheker frieze , a special ornamental border-like shape of the border showing columns (see Gardiner list , symbols Aa30 (A) and Aa31). The design of the ceiling imitates mat cladding supported by wooden beams.

The painter is well acquainted with the traditions from the time of Amenhotep II , but uses more innovative and progressive elements from the time of Thutmose IV in his own work , which suggests a date in his reign. As many postures or movements show, for example, the artist had a good gift for observation. He varied between strict depictions in religious scenes such as the sacrificial situations and more relaxed scenes such as festivities, hunting and agriculture. Sometimes he even sprinkles caricatures and new ideas. You can see shaggy figures, the beginnings of the belly of the wine-making workers, the harpist's belly folds or the bald head of a farmer reminiscent of a tonsure . Brush duktus , color and composition suggest that a single painter decorated the grave. His special class is illustrated not least by his masterly free brushwork.

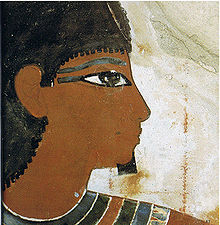

Image 1: victim scene

The scene of the sacrificing grave lord and his wife is a common motif in tomb painting of the time and is not missing in almost any of these graves. The sacrificial scene is shown in a similar form on both sides of the entrance. The couple stands in front of a high-piled sacrificial building. A rich offering is made to the gods. The sacrificed goods are typically shown spread out. Night makes the sacrifice by pouring myrrh and frankincense from a vessel over the sacrificial building. Lady Taui stands next to her husband and seems rather uninvolved. In one hand she holds a menat , in the other a musical instrument in the form of a bowstring . The objects show her in her function as the temple singer of Amun. The victim scene alludes to the annual valley festival in Theben-West. The gods to whom sacrifices are made here are not depicted in figures, but are named in inscriptions above the heads of the couple. They are the realm god Amun-Re , the sun god Re-Harachte and the death god Osiris as well as the smaller gods Hathor and Anubis . The image of the couple with the victim is probably the most important representation in the grave, as night and Taui are very large and in festive garments and occupy almost the entire height of the wall. As in all other depictions, Nacht wears conservative clothes here.

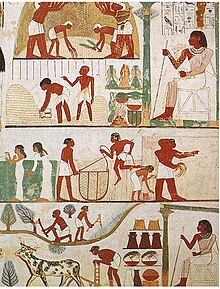

Photo 2: Agriculture

Since the Old Kingdom , the depiction of agricultural scenes has been a popular motif for depictions in graves, even if the person buried there had no relation to agriculture. Such representations showed the care of the deceased in the afterlife .

On the right, Nacht is enthroned on a kiosk and observes the work. On the other side of the picture you can see a worker who is drinking from a water bag. In between, a bump runs through the picture, which among other things surrounds a small lake and thus wants to show a landscape-related spatiality. You can see farmers sowing, clearing trees and chopping a vegetable field. In addition, two teams of cattle are shown plowing. In the register above you can see a group of farmers with sickles, followed by a harvester, next to two farmers who are trying to tame an overflowing carrying basket. One of the two is painted during a jump, which is reminiscent of a time lapse or slow motion . At the end of the picture you see two girls in front of a flax field. Above that, on the right edge, night is shown sitting in a kiosk. It takes the place of two registers. There is an inscription:

- Sitting in the hall and inspecting his fields , through the hour priest of Amun, night, the justified by the great God.

According to this, Nacht supervised the work on his own fields. He observes the grain knife in the middle register when measuring the amount of grain, above it in the top register grain throwers, who free the grain from the remains of the husks and straw by throwing it into the air.

Photo 3: false door

The left narrow side served as the main cult site of the grave. A false door is shown in the center of the page. It is speckled in red and is supposed to imitate roses in granite . The false door was the most important element in an ancient Egyptian tomb because, according to the Egyptians, false doors were a connection to the world of the dead and the deceased can go through this into the world of the dead and return to the tomb. In addition, he could receive sacrifices made here. That is why six kneeling gift bearers are shown strictly symmetrically around the door . The offerings they have made are explained by inscriptions, including water, beer, wine, clothing and ointments. Under the door in the middle rises a high, figurative sacrificial structure, which is equipped with bread, fruit, vegetables, meat and poultry. A woman is shown on both sides in a vest and a tree as a headdress. The trees and other offerings in their hands identify them as personifications of fertility. At the edge, other gift bearers come up with offering tables in their hands.

Photo 4: The "Beautiful Festival of the Desert Valley"

The most famous details of the frescoes of the tomb are within this image. Today it is in the worst condition of any painting of the Night Grave. Celebrations on the occasion of the " Beautiful Festival of the Desert Valley " are shown. During the festivities, cult statues of the gods Amun, Mut and Chons were brought in a solemn procession from Karnak to West Thebes to symbolically visit the mortuary temples in the Valley of the Kings . The destination was the valley basin of Deir el-Bahari . During this festival the families of the area gathered in front of the graves of their ancestors to celebrate with them, probably in the forecourt of the graves. In addition, the other cult rooms were probably also included in the festivities.

Amenemope, the sacrificing son of the night, in front of a sacrificial table with rich gifts, and his parents sitting behind it, are shown in the lower register, in the second overarching register. Under her chair, which resembles a bench, is one of the most famous details of the paintings from this tomb, a cat eating a fish. With her you can see the decay of the pictures as an example. While the depiction is still completely intact on Davies copy, part of the underside of the animal is missing today. The most famous and to this day most widespread scene from this grave follows. You can see a group of three musicians: a harp, a lute and a flute player. The individuality of the individual figures and their collective composition is always particularly emphasized when they are included in the tomb paintings. The musicians occupy about one and a half registers, above which additional offerings are shown to fill up the second register. On the left in the lower register there are three seated women, above in the second register three seated men, certainly party participants. While the musicians playing in front of them are shown individually and in motion, the six people are painted very stiffly and schematically. Above these two lower registers, only the larger part of another register can be seen. Here, too, a familiar scene is depicted, a blind musician playing the harp. He is sitting cross-legged in front of six women attending the party. These are stored on a papyrus mat. The one closest to the harpist smells a lotus flower . Behind it you can see two women with fruits in their hands and finally a group of three in a row, served by a small, almost completely naked, female figure. The wigs of women, who followed a frequently changing fashion during the times of Amenhotep II and Thutmose IV, make dating easier. The traditional three-part wig can only be seen on the tree goddesses on the false door side. The participants in the festival are all shown with the modern one-piece wig, which in turn is shown in several variations. For example, the lengths and hairstyle shapes differ here. However, the hairstyle fashions did not alternate directly, but sometimes continued to exist side by side. The newer hairstyles shown are stylistically just like the dresses of the ladies who are worn at the festival - slightly yellowish discolored, tight-fitting, the hem pulled over the heel to the floor and combined with a wide, transparent cape that holds one arm or one Shoulder covered and appears to be knotted in front of the chest - clearly in the time of Thutmose IV.

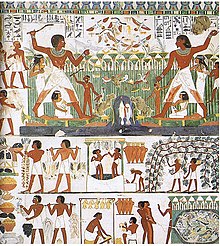

Image 5: Hunting, grape harvest and bird trapping

The image is divided into two main registers. On the left side of both registers, Night and Taui are shown again in front of a large pile of offerings. Both observe the processes that lead to the provision of the gifts. In the lower register of the two-part register you can see a large beating net filled with birds and the plucking and gutting of the birds. The small register above shows the grape harvest , the pressing of the grapes, the collecting of the must in a basin and the filling into amphorae .

The upper register is dominated by a single display. You see night twice in a large representation while hunting in the papyrus thicket. One time he holds a throwing stick with which he hunts for poultry, the other time his posture indicates fishing with a spear. However, the spear was not made by the painter. Nacht is accompanied by his wife, three children and his servants. Not only the hunt, which is recognizable at first glance, is shown; rather, an image motif known since the Old Kingdom is passed on, which is also firmly rooted in religious ideas. The papyrus thicket is a mythical place of fertility and regeneration . That is why the family members are shown who would not actually have been present during the sporting leisure pursuit of the hunt. The representation of the family symbolizes a posthumous generation of offspring. The hunting aspects of the picture, for their part, are a symbol of victory over the chaotic forces that threaten the divine world order. In general, some aspects in the mostly rather conservative representation of the night point to the reign of Amenhotep II, but here the relatively broad belt suggests a date to the time of Thutmose IV.

The representations on this wall are also based on common shapes, some of which have been in use since the Old Kingdom. The opposite representation of the grave lord already exists in the tomb of Sabni in Aswan from the sixth dynasty and in the tomb of Menena, which was also found in Thebes-West and is dated around the same time as the tomb of the night. The depiction of a fish hunt in the grave of Userhet and in the grave of Anchtifi, which was found in Mo'alla and is dated to the first interim period, also dates from this period and from a Theban grave . However, none of these representations can compete with the splendor of color in the grave at night today.

Photo 6: victim

The narrow wall on the right, which is opposite the false door wall and thus the main cult site, also addresses the material provision of the deceased in the realm of the dead. This figure is also divided into two tabs. Both are about the same size and show Nacht and his wife sitting at overloaded sacrificial tables. You can see bread, meat, fruit and baskets full of blue grapes. Below are jugs and bouquets of rods wrapped in lotus flowers .

In the upper register, two rows of sacrificial bearers pass the deceased, led by a priest dressed in a panther fur. The porters bring flowers, vessels of oil and ointment. In the lower register there are four individual priests who also bring gifts. The paintings on this wall have not been completed.

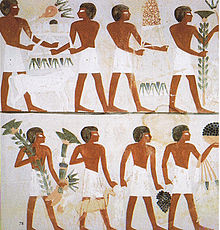

Photo 7: Gift carrier

This wall is the counterpoint to the first picture with the agricultural scenes. Instead of these scenes, however, victims are again shown in three registers. There are four in each of the two upper registers and three in the bottom three. They bring papyrus plants, grapes, poultry, desert gazelles and calves that are intended for the burnt offering of the night. They are also intended for cultic care for the deceased. Both the detail scenes and the lowest, fourth register are missing on this wall.

See also

literature

- Norman de Garis Davies : The Tomb of Nakht at Thebes (= Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition. / Robb de Peyster Tytus Memorial Series. Volume 1). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (NY) 1917.

- Nina de Garis Davies : Ancient Egyptian paintings. Selected, copied and described. 3 volumes, Chicago University Press, Chicago (Ill.) 1936, volume 1, plates XLVII-XVLIII.

- Sigrid Hodel-Hoenes: Life and Death in Ancient Egypt. Scenes from private tombs in new kingdom Thebes. Cornell University Press, Ithaca (NY) et al. 2000, ISBN 0-8014-3506-4 , pp. 27-41.

- Also: life and death in ancient Egypt. Theban private graves of the New Kingdom. Special edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1992, ISBN 3-534-11011-0 , pp. 35–47.

- Friederike Kampp : The Theban Necropolis. To the change of the grave idea from the XVIII. until XX. Dynasty. (= Theben 13), von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1506-6 , pp. 257-258.

- Lise Manniche : Lost Tombs. A Study of Certain Eighteenth Dynasty Monuments in the Theban Necropolis (= Studies in Egyptology. ). KPI, London et al. 1988, ISBN 0-7103-0200-2 , pp. 171-72.

- Lise Manniche: City of the Dead. Thebes in Egypt. British Museum, London 1987, ISBN 0-7141-1288-7 .

- Matthias Seidel , Abdel Ghaffar Shedid: The grave of the night. Art and history of an official grave of the 18th Dynasty in Thebes-West. von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1332-2 .

- Kent R. Weeks , Araldo de Luca: In the Valley of the Kings. Of funerary art and the cult of the dead of the Egyptian rulers. Weltbild, Augsburg 2001, ISBN 3-8289-0586-2 , pp. 391-397.

- Dietrich Wildung : Egyptian painting. The grave of the night (= Piper Gallery. ). Piper, Munich et al. 1978, (also special edition: Seehamer, Weyarn 1997, ISBN 3-932131-05-3 ).

Web links

- Nakht - TT52. TT52, the grave of the night and his wife, Tawy (English)

- The Tomb of Nakht on the West Bank at Luxor. (English)

- Recording of the grave

- Recording of the grave

Individual evidence

- ↑ Directeurs de l'IFAO depuis sa fondation

- ↑ Manniche: City of the Dead. 116-117; Manniche: Lost Tombs , 171–72, plate 55, no. 83

- ^ Tour Egypt

- ↑ a b Seidel, Shedid: The grave of the night. P. 13.

- ↑ Arne Eggebrecht : Foreword , in Seidel, Shedid: Das Grab des Nacht , p. 7.

- ↑ Seidel, Shedid: The grave of the night. Pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Davies: The tomb of Nakht. Plate XXVIII

- ^ Translation after Jan Assmann : Sun Hymns in Theban Graves , 1983, p. 64.

- ↑ Davies: The tomb of Nakht. Panel XXIX; Seidel, Shedid: Das Grab des Nacht , p. 19.

- ↑ Seidel, Shedid: The grave of the night. Pp. 19-21.

- ↑ Seidel, Shedid: The grave of the night. Pp. 21-22.

- ↑ Seidel, Shedid: The grave of the night. Pp. 29-30.

- ↑ Seidel, Shedid: The grave of the night. P. 15.

- ↑ Davies: The tomb of Nakht. Plates XX, XXI; Seidel, Shedid: Das Grab des Nacht , pp. 15-17.

- ↑ a b Seidel, Shedid: The grave of the night. P. 17.

- ↑ Dr. Dietrich Volkmer

- ↑ Davies: The Tomb of Nakht. frontispiece

- ↑ Davies: The Tomb of Nakht. Panel XV, XVII; Seidel, Shedid: Das Grab des Nacht , p. 28.

- ↑ Davies: The Tomb of Nakht. Panel XXIV; Davies: Ancient Egyptian Paintings , Plate XLVII

- ↑ Seidel, Shedid: The grave of the night. Pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Davies: The Tomb of Nakht. Panel XXVI; Seidel, Shedid: Das Grab des Nacht , p. 29.

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage : Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998 ( Kulturgeschichte der Antiken Welt , Volume 70), especially pp. 30–49.

- ↑ Seidel, Shedid: The grave of the night. P. 18.

- ↑ Seidel, Shedid: The grave of the night. P. 19.

Coordinates: 25 ° 43 ′ 54.6 ″ N , 32 ° 36 ′ 35.8 ″ E