inscription

Under inscriptions refers generally characters (mostly font , rare symbols ) that are embedded on a stable support, in the majority of objects with a fixed location. However, there is no precise and undisputed definition of the term. Linguistic representations are primarily memorial , grave, consecration , honorary, sculptor, building release inscriptions , vows , gifts to gods, decrees , inscriptions under private and sacred law.

definition

The definition of the term “inscription” is vague and cannot be formulated completely clearly. The word is a loan translation of the Latin "inscriptio". In antiquity, this referred to the “inscription” on an object or the “heading” of a text; the Latin word has only been understood in its narrower meaning today since the 16th century. The German and the Latin term correspond to the Greek "ἐπιγραφή" ("Epigraphé"), which literally also means "inscription" or "inscription" and from which the term epigraphy for the science of inscriptions is derived.

Since these terms could theoretically designate any form of writing, they are usually defined according to the practical requirements of research: Everything that epigraphy deals with is considered an inscription. This is the definition of the historian and archivist Rudolf M. Kloos in relation to the inscriptions of the Middle Ages and the modern age : “Inscriptions are inscriptions of various materials - in stone, wood, metal, leather, fabric, enamel, glass, mosaic, etc., which are produced by forces and methods that do not belong to the writing school or chancellery. ”Thus, the writing methods learned in schools or used in state administration ( pen , pen, etc.) are excluded and all other written documents are summarized as inscriptions. The French palaeographer Jean Mallon formulated similarly for antiquity : Epigraphy for this epoch deals “with all graphic monuments, with the exception of those written in ink on papyrus and parchment”.

In practice, however, two other groups of materials are excluded from the inscriptions, since they are also researched by their own specialist disciplines: the coins , the subject of numismatics , and the seals , which are concerned with sphragistics . However, even within numismatics, the inscription in the field of a coin is called "inscription".

Other attempts to define and narrow down the term “inscription”, which relate to the specific external form or function of a document, have also been discussed, but have not been successful:

- A frequently encountered definition is that all written documents on "permanent" materials are to be regarded as inscriptions. This applies to the great majority of the surviving inscriptions, which were made, for example, in stone or metal and many of which were even explicitly created, since the writing of a fact on stone promised to fix the content for a longer time than the sole publication, for example, on papyrus or parchment. This applies, for example, to inscriptions that make a law or ordinance public, remind of a charitable donation or a building project (see house inscription ) or ensure the memory of a deceased person ( grave inscription ). At the same time, however, scratches on wooden tablets and even embroidery on cloths are referred to and treated as inscriptions, so that durability alone is not a sufficient criterion.

- Attempts were also made to define inscriptions more narrowly by means of the characteristic of publicity. Like the criterion of durability, this limitation also applies to many important groups of inscriptions, but leaves out other types of inscription material. These include, for example, bell inscriptions , but also the numerous written documents that were placed inside coffins or grave buildings and thus inaccessible to every visitor.

- After all, scientists have wanted to narrow down inscriptions about their monumentality . A large format is, however, conducive to the permanent presentation of a text or the most effective possible publicity, but it does not apply to all inscriptions. For example, there are numerous inscriptions on objects of everyday use (referred to as instrumentum domesticum in ancient epigraphy ), but also scribbles on walls or stonemasons' marks on many buildings from antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Function, material and technology

Inscriptions are often carved in stone . It is not uncommon for the letters to be colored or gold-plated. In ancient times , the letters were often traced with red paint. Also metal casting or engravings find inscriptions use. Sgraffito (scratch plaster) is a special technique . In addition, sharp objects are scribbled or scratched in walls or other material, and painted with paint on wood or walls ( graffiti ).

Via the visual perception , certain feelings should be addressed and triggered by the way of representation, such as appreciation , dignity , sublimity , esteem , respect , awe and others. This role is not necessarily realized or supported by a corresponding size, but above all by the targeted use of creative graphic / plastic means. The material used and the technology are an integral part of the aesthetic effect.

exploration

The oldest inscriptions known to us come from early antiquity. As historical sources, they are particularly important for research into antiquity and the Middle Ages. They supplement and correct the knowledge about the living environment from this time and help to reconstruct history. Inscriptions are investigated by a separate discipline, as auxiliary historical science applicable epigraphy . The number of ancient inscriptions is in the hundreds of thousands. Since 1853, the Latin inscriptions have been recorded by the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum institution from the entire area of the former Roman Empire in a geographical and systematic order. Since its establishment by Theodor Mommsen, it has been the authoritative documentation of the epigraphic legacy of Roman antiquity.

Lasting effect of the classical Roman inscriptions

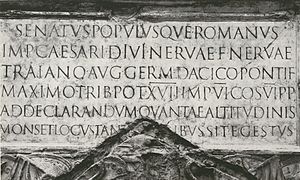

From the great variety of ancient inscriptions, the monuments of the Roman Empire stand out in their significance for the history of writing . The representatively designed letters of the Capitalis Monumentalis represent a crystallization point in the development of the Latin alphabet . In these ancient masterpieces by the font designers and stonemasons, the aesthetic form of the Latin capital letters has reached its climax. At the same time, the shape of the letters (except for H, J, K, U, W, Y and Z, which were only added later) was finally determined, canonized .

Intensive preoccupation with classical inscriptions began in the Renaissance . Many artists and scientists, including Albrecht Dürer , the mathematician Luca Pacioli and Francesco Torniello , have dealt with the canon of forms of majuscules . With the help of geometric measurements, they tried to make the beauty of this alphabet didactically transparent. The elegance and clarity of this typeface are based primarily on the proportions of the letters, the bold-fine contrast in the lines, its serifs and finally on the rhythm inherent in the overall typeface. The humanists adopted these capital letters in their typefaces, the humanistic minuscule and the humanistic italic . Both formed the models for the first Latin printing types : the Antiqua and the Italic . The artistically mature forms of the classical Roman inscriptions have set aesthetic standards for over 2000 years up to the present day. One of the most famous examples from this period is the inscription on Trajan's Column (114 AD). The capitalis monumentalis, or classical Roman capital, is also a fundamental orientation for contemporary type designers .

See also

- Bustrophedon

- Stumbling blocks

- Roman lead pipe inscription

- Epitaph

- Dedicatory inscription

- Trajan (font)

literature

- Albert Kapr : German writing. A textbook for writers . Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1955.

- Edward M. Catich: Letters Redrawn from the Trajan Inscription in Rome. The Catfish Press, 1961.

- Jan Tschichold : Master book of writing. A textbook with exemplary fonts from the past and present for type painters, graphic artists, sculptors, engravers, lithographers, publishers, book printers, architects and art schools. 3rd un. Reprint of the 2nd edition. Otto Maier-Verlag, Ravensburg 1965, ISBN 3-473-61100-X .

- Edward M. Catich: The Origin of the Serif: Brush writing and Roman letters . The Catfish Press, 1968.

- Albert Kapr: Fonts. History, Anatomy and Beauty of the Latin Letters . Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1971, ISBN 3-364-00624-5 .

- Albert Kapr: Aesthetics of the Art of Writing. Theses and marginalia . Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1977.

- Walter Ohlsen: Proportional analysis of the inscription of the Trajan column , Friedrich Wittig Verlag, Hamburg 1981. ISBN 3-8048-4222-4 .

- Helga Giersiepen, Clemens Bayer: inscriptions, written monuments. Techniques, history, occasions. Falken Verlag, Niedernhausen 1995, ISBN 3-8068-1479-1 .

- Thomas Neukirchen: Inscriptio. Rhetoric and poetics of the astute inscription in the Baroque era (= studies on German literature. Volume 152). Tübingen 1999, ISBN 978-3-484-18152-6 .

- Bernhard Bischoff : Palaeography of Roman antiquity and the western Middle Ages (= basics of German studies. Volume 24). 3rd unchanged edition Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-503-07914-9 .

- Anne Kolb , Joachim Fugmann : Death in Rome. Grave inscriptions as a mirror of Roman life (= cultural history of the ancient world. Volume 106). Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2008.

Web links

- German inscriptions online. The inscriptions of the German-speaking area in the Middle Ages and early modern times (DIO). Academy of Sciences and Literature Mainz, accessed on May 11, 2016 .

- Research group "Religious and cultural transfer in antiquity" at the University of Erfurt

- Werner Eck: Introduction to Latin Epigraphy (PDF; 2.7 MB)

Remarks

- ^ Walter Koch : Inscription palaeography of the occidental Middle Ages and the early modern times: early and high Middle Ages. R. Oldenbourg, Vienna / Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-7029-0552-1 , p. 25.

- ↑ Rudolf M. Kloos: Introduction to the epigraphy of the Middle Ages and the early modern period. 2nd edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1992, ISBN 3-534-06432-1 , p. 2.

- ^ Jean Mallon: Paléographie romaine (= Scripturae. Volume 3). Consejo superior de investigaciones científicas, Instituto Antonio de Nebrija de filologia, Madrid 1952, p. 55.

- ^ Walter Koch: Inscription palaeography of the occidental Middle Ages and the early modern times: early and high Middle Ages. R. Oldenbourg, Vienna / Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-7029-0552-1 , p. 24.

- ↑ Helmut Kahnt, Bernd Knorr: Old dimensions, coins and weights. A lexicon. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig 1986, licensed edition Mannheim / Vienna / Zurich 1987, ISBN 3-411-02148-9 , p. 385.

- ↑ Manfred G. Schmidt : Introduction to Latin epigraphy. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-14343-4 , p. 1; Walter Koch: Inscription palaeography of the occidental Middle Ages and the early modern period: early and high Middle Ages. R. Oldenbourg, Vienna / Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-7029-0552-1 , p. 23.

- ^ A b Walter Koch: Inscription palaeography of the occidental Middle Ages and the early modern times: early and high Middle Ages. R. Oldenbourg, Vienna / Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-7029-0552-1 , p. 23.

- ↑ See also Helmut Häusle: The monument as a guarantee of post-fame. A study of a motif in Latin inscriptions. Munich 1980 (= Zetemata. Volume 75).

- ^ Dürer, Albrecht: Underweysung the measurement, with the Zirckel and Richtscheyt, in lines, levels and whole corporen, Nüremberg, 1525. Page 115 and following. On-line

- ↑ Luca Pacioli: Divina Proportione. The doctrine of the golden section - According to the Venetian edition of 1509 , pp. 359, 361 u. 363 [1]

- ^ Walter Ohlsen: Proportional analysis of the inscription of the Trajan column , Friedrich Wittig Verlag Hamburg, 1981. ISBN 3-8048-4222-4

- ↑ Example of the takeover of the Capitalis monumentalis in the humanistic minuscule

- ↑ Example for the transfer of the Capitalis monumentalis into the humanistic cursive ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Various views of the inscription on Trajan's Column here , here and here