Djoser pyramid

| Djoser pyramid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

View of the Djoser pyramid from the southeast

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The step pyramid of the ancient Egyptian king Djoser ( Djoser pyramid , also Netjerichet pyramid ) from the 3rd dynasty of the Old Kingdom around 2650 BC. BC is the oldest, with a height of 62.5 meters the ninth highest of the Egyptian pyramids and one of the few with a non-square base.

With this building the first phase of the pyramid construction in Egypt and the monumentalization of the royal tombs began. The step pyramid itself is enclosed by the largest of all pyramid complexes, which contains a large number of ceremonial buildings, structures and courtyards for the cult of the dead. After Gisr el-Mudir, a few hundred meters west of the pyramid, it is considered to be the second oldest preserved building made of hewn stones in Egypt .

As the central building of the necropolis of Saqqara it belongs as part of the Memphis necropolis since 1979 to UNESCO World Heritage Site .

exploration

The pyramid complex was examined for the first time in 1821 by the Prussian consul general Heinrich Menu Freiherr von Minutoli and the Italian engineer Girolanio Segato. The entrance to the pyramid was discovered. In the corridors, the remains of a mummy were found in a corner , namely a gilded skull and gilded soles, which Minutoli believed to be the remains of the Pharaoh. Although the objects were lost due to the shipwreck of the Gottfried on the crossing to Hamburg , it is certain that it was a secondary burial from a later time.

In 1837 John Shae Perring found numerous other secondary burials in the aisles. He also discovered the galleries under the pyramid.

From 1926 onwards, Cecil M. Firth conducted a more systematic investigation that he was unable to finish due to his death. James Edward Quibell was in charge of the excavation until he died in 1935. Jean-Philippe Lauer , who worked with Quibell, continued the research. In 1932 Lauer measured the underground chambers and passages. In 1934 he found further body fragments in the burial chamber which, after an initial examination, had been stored in the University of Cairo until 1988 . Lauer believed they had found the pharaoh's remains, but closer inspection after their retrieval revealed that they were from several people. A radiocarbon dating showed that the body parts of a secondary burial from the Ptolemaic era came.

Lauer dedicated his life to exploring the Djoser pyramid and the Saqqara necropolis until his death in 2001. Various buildings and wall sections of the complex were also reconstructed under Lauer's direction.

Research by a Latvian team led by Bruno Deslandes has been able to identify several previously unknown tunnels in the pyramid complex since 2001.

Construction of the pyramid and the complex

Djoser, who at his time was known by his Horus name Netjerichet, had his tombs planned and built by Imhotep ( high priest of Heliopolis ), Iri-pat ( "member of the elite" , top lecture priest , head sculptor and site manager).

Circumstances of construction

Djoser had an unprecedented monumental grave built during his 19-year reign (approx. 2665–2645 BC). This period was evidently marked by political stability, increasing prosperity and advances in science and construction.

When choosing the location for his tomb, Djoser chose the Saqqara necropolis. The pyramid complex was located near the tombs of the kings of the second dynasty, Hetepsechemui , or Raneb and Ninetjer, and the large enclosure Gisr el-Mudir , apart from the mastaba tombs of the first dynasty. However, the complex was not built on pristine land, but there was already an older necropolis on the area , as can be seen in the staircase graves in the north.

Development of the step pyramid from earlier burial structures

The pyramid complex did not arise spontaneously, but represents a synthesis of various Upper and Lower Egyptian burial practices. It was the preliminary high point in the development of the tombs of the kings of the 1st and 2nd dynasties from Abydos . The step pyramid and its surrounding facilities represent a combination of the two components of the grave building and the valley district.

However, elements of the graves and facilities of the Saqqara necropolis can also be found. The large enclosure (Gisr el-Mudir), as a stone equivalent of the valley districts of Abydos, may have served as a model for the enclosure of the pyramid district. The gallery graves of the second dynasty in Saqqara are also models for the extensive galleries in the Djoser pyramid district.

The pyramid itself is a further development of the grave mounds symbolizing the mythological " original mound", as can be found at royal tombs in Abydos. The hill structure was also incorporated into the mastaba tombs of Saqqara. So one finds z. B. a concealed burial mound inside the Mastaba S3507 . In the Mastaba S3038 , this inner burial mound was reproduced by a stepped brick mound, which is a direct predecessor structure to the pyramid.

The step pyramid

The step pyramid is located in the center of the grave district. However, Imhotep originally planned it not as a pyramid, but as a square mastaba .

Development from the mastaba to the step pyramid

According to Jean-Philippe Lauer, the mastaba was expanded into a step pyramid in five additional construction phases (a total of six). On the south and east sides of the pyramid, the individual phases of the expansion can still be seen very clearly. With the completion of the six construction phases, the step pyramid received six steps and reached a height of around 62 m, with a rectangular base area of approx. 121 × 109 m.

The following construction phases can be distinguished:

- Mastaba M1 : In the first step, a square mastaba with an edge length of 63 meters and a height of eight meters was erected, which differed from previous mastabas in two essential ways: On the one hand, all previous mastabas had a rectangular floor plan and, on the other hand, the Djoser mastaba was the first which was completely made of limestone . The mastaba M1 received an external cladding made of fine limestone. The substructure was hewn out of the rock under the structure for this phase. The shaft of the burial chamber ran through the structure to the roof of the mastaba.

- Mastaba M2 : In the second phase, the mastaba was expanded to an edge dimension of 71.5 m. The new component only reached a height of seven meters, so that a stepped appearance was created. The eleven galleries on the east side of the mastaba were built during this construction phase.

- Mastaba M3 : The third construction phase only extended the mastaba on the east side to 79.5 m, so that the shafts of the east galleries were covered by the new, only five-meter high component.

- Pyramid P1 : The fourth construction phase converted the mastaba into a four-step pyramid of 85.5 m × 77 m. The core of the building was made of coarse stones and clad with finely crafted stones. The wall layers were no longer horizontal as in the mastabas, but inclined inward by 17 ° to give the masonry more stability. This phase did not get past the height of the original mastaba.

- Pyramid P1 ' : In the fifth phase, the small pyramid was covered by a four- or six-tier pyramid measuring 119 m × 107 m in area. As a result of this expansion, the original access to the substructure was no longer accessible and a second access was created, which came to the surface in the floor of the mortuary temple on the north side. Significantly larger stones were now used in the masonry. In this phase, too, only the first stage was completed before a new expansion was started.

- Pyramid P2 : The sixth and final construction phase enlarged the pyramid again to a base area of 121 m × 109 m (231 by 208 cubits) with a total of six steps, which reached a height of 62.50 m. In the west, the lowest level is based on the western massifs that have already been built. The top step had a rounded end and, together with the pyramid core, forms a flat surface. So there was probably no pyramid apex.

In addition to the core structures for the four or six-tier pyramid, Lauer specifies seven or eleven layers without the outermost cladding layer. He is of the opinion that the cladding layers of construction stages P1 and P2 were only applied after the completion of the individual layers. The pyramid P1 was therefore completely built before the last expansion with the pyramid P2. The question of whether the pyramid was provided with a smooth outer surface is answered in the negative by Stadelmann. In addition, excavations at the northwest corner of the pyramid in 2007 show that no remnants of limestone cladding were present.

Substructure of the pyramid

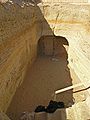

The burial chamber was laid out in a 28 m deep shaft with a base area of 7 × 7 m. It consists of precisely hewn rose granite blocks in four layers. The burial chamber was accessed from a so-called "maneuvering chamber" above it through a circular hole about one meter in diameter. The access was closed with a 3.5-ton granite stopper, which was lowered from the maneuvering chamber with ropes. Finds of alabaster and limestone fragments with star patterns around the burial chamber suggest that these are remnants of the maneuvering chamber, as the material and decoration are similar to those of the maneuvering chamber in the south tomb. On the other hand, Lauer suspected that the granite burial chamber replaced a burial chamber that had been installed in an earlier construction phase.

After the digging and maneuvering chambers had been placed in the shaft, it was walled up around the chambers, then largely filled with loose material and the upper end walled up again. The backfill and the maneuvering chamber were cleared out in the 26th Dynasty (Saïten period).

A gallery complex is laid out around the burial chamber in all directions . The individual galleries are connected to one another by corridors. In the east gallery there are four rooms clad with blue faience tiles , similar to those in the south grave. The tiles, separated by raised spaces, are an imitation of reed mat curtains . The blue tiles express the watery character of the underworld in Egyptian mythology . There are also three bas-reliefs depicting the king at the Sed festival . The complex appears unfinished - especially when compared to the south grave.

Blue faience tiles from the substructure of the Djoser pyramid in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

Blue faience tiles from the substructure of the Djoser pyramid in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

The second substructure consists of the eleven east galleries. In the second construction phase of the mastaba (M2), eleven 30 m deep shafts were dug on the east side, each of which has a gallery corridor in a westerly direction below the actual substructure. The corridors were numbered from north to south by the excavators. The middle galleries are each curved outwards so that the area of the central shaft of the primary substructure is avoided. The first five shafts (I-V) were used to bury members of the pharaoh's family and were looted in ancient times. There were two in the corridors Alabaster - sarcophagi found as well as fragments of other sarcophagi and grave goods.

The remaining shafts, however, were intact and contained over 40,000 vessels made of ceramic and alabaster, which were identified by inscriptions as grave goods from the 1st and 2nd dynasties . Although largely broken by the collapse of the ceilings, these items form an important source of art from the early Dynastic period. Possibly it concerns a new burial of grave goods from damaged old graves restored by Djoser. The reason why these vessels, but not other grave goods, were moved to the galleries of Djoser's grave has not yet been clarified.

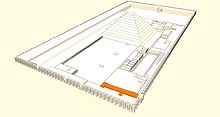

The pyramid complex

The pyramid complex of the Djoser pyramid is the largest of all Egyptian pyramids. In the execution of the elements of the complex, some were implemented in functional architecture, but others in a so-called fictional architecture. While the former buildings probably had a function in the funeral ceremony, the latter served the Pharaoh's Ka in the afterlife. It was enough that the exterior of the elements had the correct appearance, while the interior could be neglected.

It is noticeable that certain elements of Egyptian architecture , which in this worldly architecture consist of perishable material such as wood and reed mats, are not missing here, but have been reproduced in stone without function .

The pyramid complex, like the pyramid, was built in two phases. The dimensions of the originally, smaller pyramid area can be seen from the wall foundations north of the pyramid. In the east, this first phase of construction was probably limited to the western massifs.

The elements of the system are described below.

| Elements of the pyramid complex | |

Big ditch

The entire district is also enclosed by a large, 40 m wide ditch. This reaches an extension of 750 m in a north-south direction. The depth of the trench is unknown as previous excavations have only been carried out to a depth of five meters. On the south side, the trench carved out of the rock is not closed in on itself, but the western wing is a little shorter, so that an overlap arises. The entrance to the complex was probably between the ends of the moat. An Egyptian research team was able to prove during excavations in the southern area that the walls of the trench were provided with niches. Today the trench is largely buried, but can be clearly seen on aerial photographs.

According to Swelim , the niches could represent a symbolic replacement for the secondary graves of the 1st Dynasty, which took the servants of the deceased Pharaoh with them into the afterlife.

In addition to its symbolic function, it is possible that the moat served as a quarry for the material used in the pyramid complex. This theory is supported by the fact that no other traces of the excavated material were found.

In the space between the northeast corner of the moat and the wall of the Djoser complex, Userkaf built his pyramid in the 5th dynasty . Unas built his pyramid complex directly to the west of the entrance . Presumably by this time the big moat was already largely buried.

Wall

The burial area is surrounded by a 1645 m long and approx 10.5 m high limestone wall in palace facade architecture, which is divided by niches and 14 false gates. As with the valley districts in Abydos, the actual entrance to the grave district is in the southeast corner of the enclosing wall . The wall encloses an area of 15 hectares and thus has an area that corresponds to a larger city at that time. In the north-south direction the extension is 545 m, in the east-west direction 278 m.

The wall consists of a core of loosely laid masonry, which is completely clad on the outside and partially on the inside with fine limestone. Every four meters an equally wide bastion protrudes from the wall. The bastions around the entrance and the false gates are wider. There are three false gates each on the north and south side, four on the west side and four false gates as well as the real entrance on the east side.

The wall differs from the enclosures of the valley districts in Abydos, but is similar to those of the archaic mastabas in Saqqara. According to Lauer, the wall could have been a replica of the palace in the then capital Inebu-Hedj (White Walls) , but this has not yet been confirmed because this palace has not yet been found. Some other Egyptologists suspect that this could be a replica of a lower Egyptian palace made of adobe bricks, as the building blocks of the wall are similar in size to the typical adobe bricks.

Entrance area

The entrance area consists of the entrance gate, the colonnade and the portico to the courtyard.

The colonnade is not oriented exactly in an east-west direction, which is attributed to the fact that it was built along a no longer existing "leaning" building that was located between the south wall and the colonnade. A total of 20 pairs of columns form the colonnade. The approximately six meter high limestone pillars were each composed of several shorter segments. Apparently not relying on the sole load-bearing capacity of the columns, they were connected to the wall behind. The surface of the pillars imitates plant material; According to Lauer, bundles of reeds could have carried light roofs at that time, or according to Ricke, palm leaf ribs that were used as protection on adobe buildings. The colonnade is divided into two areas of different lengths between the twelfth and thirteenth pairs of columns. Between the pillars and the walls there are 24 niches that, according to some Egyptologists, could represent chapels for the provinces of the empire.

In the west, the colonnade ends in a portico to the south courtyard, which is formed by four shorter columns. Remains of red paint were still found on the portico columns.

The investigation of the area showed that it was not built in one step, but in several construction stages. Fragments of statues by Djoser were also found there, the inscriptions of which bear witness to the name of Horus Netjerichet and the name of Imhoteps , which is evidence of the builder.

Lauer reconstructed the entrance area between 1946 and 1956.

South grave

The south tomb represents one of the most enigmatic elements of the Djoser pyramid complex. The structure consists of a massive, elongated mastaba-like block of limestone masonry on the south side of the courtyard. At right angles to the mastaba superstructure is a cult chapel in the northwest, which borders on the western massifs. The façades that are visible towards the courtyard are provided with niches and decorated with a cobra frieze.

The substructure of the south grave was a slightly reduced and simplified version of the substructure of the main grave, but with an east-west orientation. A descending corridor leads to a burial chamber made of rose granite, which appears as a reduced copy of the main burial chamber. The length of the chamber is 1.6 m. The maneuvering space above the chamber is preserved here. The descending corridor leads to a gallery, which, like in the main grave, was partly covered with blue faience tiles. There are also three false doors with door rolls , on each of which the Pharaoh is shown in scenes of the Sed festival .

The meaning of the south grave is still unclear. According to Firth and Edwards , it could be a makeshift grave, but a symbolic Ka grave is also conceivable, according to Ricke and Jéquier. With the latter possibility, the south grave would represent a forerunner of the later cult pyramids . It is not clear whether a burial took place in the south grave.

Südhof

The south courtyard is the largest free area in the Djoser complex. A few buildings can be found there. In the north, right by the pyramid, there is an altar . The remains of a small temple can be found in the northeast corner. On the area of the courtyard there were two limestone buildings with a “B” -shaped floor plan. The purpose of these objects has not yet been clarified, but there could be a connection to the symbolic course of the Sed-Festival (Heb-Sed) .

In the area of the south courtyard, a limestone block was found during excavations, the inscription of which attests to the restoration of the complex in the 19th dynasty by Chaemwaset , a son of Ramses II . Numerous buildings and monuments in the necropolis near Memphis have inscriptions that indicate a renovation by this prince.

Sed Fest Courtyard

On the southeast side of the complex there is an area assigned to the Sed festival , which ceremonially demonstrates the pharaoh's ability to govern. On the west side of the rectangular courtyard there are thirteen chapels, which were built in two different designs. The Seh-netjer ( god's shadow ) type has a flat roof and semicircular elevations on the edges. At the approach to the roof there is an imitation of outstanding palm leaves. The Per-wer type has a round roof and pilasters on the facade. Some of the chapels have false doors . There are twelve other chapels on the east side of the courtyard, but they are smaller. All chapels are designed as pseudo-architecture. This suggests that they were not intended for actual use in the context of Sed festivals, but for otherworldly use in the context of the ruler's cult, which should enable the dead ruler to celebrate Sed festivals in all eternity. Some of the chapels have been completely reconstructed.

Temple "T"

The rectangular building located between the Sed-Fest chapels and the south courtyard, which Lauer gave the working name Temple "T" , was apparently a temple that was included in the Sed Fest ceremony. Similar to other buildings in the pyramid complex, the usual mud brick construction was also transferred here in stone, whereby this was a functional architecture. The temple consisted of an entrance colonnade, an antechamber, three inner courtyards and a hall with a square floor plan. Entrances to the temple were on the east and south. The limestone ceiling was supported by pillars.

Mortuary temple

The mortuary temple was on the north side of the pyramid and formed the central element for the ruler's cult . It had an east-west orientation and was entered through an entrance in the south-east, which imitated an open wooden door in stone construction. A portico made of double columns led from the entrance to the inner area. The floor of the temple was slightly raised compared to the surrounding structures.

Numerous corridors, galleries and rooms form the interior of the temple. The interpretation and reconstruction of the various components of the temple is difficult because its structure differs significantly from all later mortuary temples.

The temple structure included two courtyards that were east and west of the center of the temple. The access stairs to the pyramid were also in the western courtyard.

The mortuary temple was probably originally planned further south, but had to be moved further north as the pyramid was enlarged several times. The mortuary temple was originally planned to be much larger and the northern areas were filled in as a solid mass, presumably in order to complete the temple quickly after the death of the pharaoh.

Serdab

The Serdab (Arabic cellar) is a small chamber east of the mortuary temple on the north side of the pyramid. The whole Serdab, like the building blocks of the pyramid, is inclined inwards by 17 °. In the Serdab Chamber was a life-size statue of Djoser, which was made of limestone and depicts the ruler sitting strictly on the throne. There are two holes in the north side of the chamber that should allow the statue to see the rituals performed in the courtyard. The inclination of the chamber can also be interpreted as an orientation towards the circumpolar stars .

The original of the statue is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo , while a replica is on display in the Serdab. During the reconstruction, a side stone of the Serdab was replaced by a pane to allow visitors a look inside.

Statue fragments that resemble the Serdab statue were found in the area of the mortuary temple, which could indicate a possible second Serdab.

North and South Pavilion

The south house was an elongated building, which presumably (according to Lauer) was a replica of a wooden frame construction with a rounded flat roof. The roof was supported by several rows of four stone half-columns, the red and black paintwork to simulate cedar trunks. The interior of the building was filled with solid masonry, similar to the Sed-Fest chapels. An L-shaped chapel was in the pavilion . On the walls visitors can see graffiti from the 18th and 19th dynasties , including the first mention of the name "Djoser". Firth found the remains of charred papyri during excavations .

The north house was constructed in a similar way to the south pavilion, but had a smaller courtyard and no altar or niches. Instead, there is a shaft to an underground gallery.

The meaning of the pavilions has not yet been finally clarified. According to Lauer, the buildings represent Upper and Lower Egypt in the form of symbolic administrative buildings in which the Pharaoh's Ka was to receive the respective subjects.

Based on the papyri finds, Firth assumed that in later times the administration of the pyramid complex was housed in the south pavilion. On the other hand, recent evidence suggests that the pavilions were purposely buried after completion, to be ready for the pharaoh's afterlife directly.

The remains of the north and south pavilions were mistaken for the ruins of secondary pyramids by the Lepsius expedition and were therefore incorrectly included in the Lepsius pyramid list under the names Lepsius XXXIII (33) and Lepsius XXXIV (34) .

West Galleries

The western massifs with their galleries below are among the most enigmatic structures of the pyramid complex. The westernmost of the three massifs extends the full length of the complex, while the other two are shorter. The superstructure is possibly built from rubble from the pyramid structure and does not contain any corridors. The superstructures must have been completed before the final construction phase of the pyramid, as it sits on the eastern massif in the west.

The substructure of the west galleries consists of long corridors and over 400 chambers. The purpose of these chambers has not yet been clarified. The general character makes them appear as storage magazines, but Lauer sees them as possible graves of Djoser's servants, who were sacrificed to serve the Pharaoh in the afterlife. However, the practice of sacrificing servants at the Pharaoh's burial was abandoned as early as the 1st Dynasty.

Rainer Stadelmann suspects that it could be the remains of an earlier grave from the early dynastic period (possibly the grave of Chasechemui ), although no usurpations of royal graves in the Old Kingdom are known.

According to Andrzej Ćwiek , the western massifs represent the very first construction phase of the Djoser tomb. After that, the tomb was initially to become a gallery tomb with a huge elongated mastaba-like structure in the style of the two tombs of the 2nd dynasty, which can be found south of the Djoser complex. This theory connects the complex with the earlier designs and avoids Stadelmann's usurpation problem.

North courtyard

The northern area of the complex has not yet been systematically investigated, but individual excavations have already produced some elements.

There is a structure known as the north altar on the northern perimeter wall. It is a high plateau that is accessible via a step ramp. There is an 8 x 8 m and a few centimeters deep depression on the plateau. The function of this element is still controversial. Stadelmann interprets it as a sun temple . The recess could then indicate the position of an obelisk . However, neither an obelisk nor fragments of one have been found.

Another magazine gallery extends from the northwest corner of the enclosing wall in an easterly direction. This probably represented granaries, as they have round filling openings in the ceiling. In addition to the seal impressions of Djoser, also those of Chasechemui were found in the north galleries, which connects them with the problematic classification of the west galleries.

In the north courtyard there are also some stair tombs that are older than the Djoser complex and come from an earlier necropolis that was built over by the Djoser complex.

Later changes to the pyramidal complex

In later times various additional shafts and galleries were dug, mainly by grave robbers.

Already at the end of the Old Kingdom, a tomb robber passage was dug from the cross gallery in the entrance area to the galleries around the burial chamber in order to plunder it. Other grave robber tunnels date back to Roman times.

Particularly striking is a gallery dug under the pyramid in the 26th Dynasty (Saïten period), the entrance of which is in the south courtyard west of the altar and which leads to the central shaft of the grave. This gallery was propped up with reused columns. With the help of this gallery, the central shaft filled with rubble was emptied and access to the grave chamber was made possible for the purpose of grave robbery . Wooden beams that were used to support the central shaft are still on site today.

More recent research by a Latvian team led by Bruno Deslandes using ground penetrating radar has also revealed indications of at least three further tunnels that were driven from outside the eastern boundary wall to the eleven east galleries, as well as another tunnel that connects the southern chambers of the main grave with the southern grave.

Importance for the pyramid development

Even if no second tomb complex was built based on the model of the Djoser pyramid, various elements were nevertheless characteristic of the style. The exact development is no longer traceable today, as the two subsequent projects - the Sechemchet pyramid and the Chaba pyramid - were not completed. In particular, the Sechemchet complex shows a close relationship with the Djoser complex, which is due to the fact that Imhotep was also the builder of this complex.

Thus, the Djoser pyramid is the only royal tomb that has been completed and preserved as a layered pyramid. A number of small provincial pyramids , built as cenotaphs , were also layered pyramids. The next completed king's pyramid, the Meidum pyramid of Sneferu , was apparently initially completed as a layered pyramid and then converted into a pyramid with an outer cladding with a constant incline in a later construction phase. All other king pyramids were basically built as real pyramids. However, two queen pyramids of the Mykerinos pyramid were later made in the form of step pyramids. The later pyramids of the 4th to 6th dynasties are also designed in a stepped construction with an outer cladding (e.g. Mykerinos pyramid, Sahure pyramid ).

It is noteworthy that initially the importance and size of the pyramid increases significantly, while the complex is reduced. The external galleries of the Djoserkomplex were integrated into the substructure of the subsequent pyramids in an increasingly reduced form. The substructure has also been simplified significantly. Elements such as the Heb-Sed-Hof or the north and south pavilions disappeared completely from the subsequent pyramid complexes, even if the Sed-Fest motif in the form of relief depictions in the mortuary temple remained present.

The mortuary temple is an element that can be found in all later pyramids. The importance of this temple increased significantly from the 5th dynasty on. However, the execution of the later mortuary temples differs from that of Djoser.

Literature and Sources

General

- Jean-Philippe Lauer : The royal tombs of Memphis. Excavations in Saqqara. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1988, ISBN 3-7857-0528-X .

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 131 ff. [The step pyramid of Netjerichet (Djoser)].

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids. Econ, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-572-01039-X .

- Frank Müller-Römer : The construction of the pyramids in ancient Egypt. Utz, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-4069-0 , pp. 143-148.

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 .

- IES Edwards : The Pyramids of Egypt. Penguin Books, West Drayton / New York 1947. (Corr. Editions Harmondsworth 1961 and 1985; German edition: Die ägyptischen Pyramiden. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1967)

Excavation publications

- Cecil M. Firth, JE Quibell: Excavations at Saqqara: the Step Pyramid. with plans by J.-P. Lurking. 2 volumes, Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1935.

- Jean-Philippe Lauer: Service des antiquités de l'Égypte. Fouilles à Saqqarah. La pyramid à degrés, l'architecture. Volume I, Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1936.

- Jean-Philippe Lauer: Service des antiquités de l'Égypte. Fouilles à Saqqarah. La pyramid à degrés, l'architecture. Volume II: Planches. Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1939.

- Jean-Philippe Lauer: Service des antiquités de l'Égypte. Fouilles à Saqqarah. La pyramid à degrés, l'architecture. Volume III: Compléments. Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1939.

- Pierre Lacau, Jean-Philippe Lauer: Service des antiquités de l'Égypte. Fouilles à Saqqarah. La Pyramide à degrés… 4, Inscriptions gravées on the vases. 1st fascicule: Planches. Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1959.

- Pierre Lacau, Jean-Philippe Lauer: Service des antiquités de l'Égypte. Fouilles à Saqqarah. La Pyramide à degrés… 4, Inscriptions gravées on the vases. 2 fascicule: texts. Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1961.

- Pierre Lacau, Jean-Philippe Lauer: Service des antiquités de l'Égypte. Fouilles à Saqqarah. La Pyramide à degrés… 5, Inscriptions à l'encre sur les vases. Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1965.

- Rainer Stadelmann: On the building history of the Djoserbe district. Grave shaft and burial chamber of the step mastaba. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 52, von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1861-8 , pp. 295-305.

Movie

- The Djoser pyramid in Saqqara. Documentation, France, 2008, 26 min., Director: Richard Copans, production: arte France, series: Baukunst, German first broadcast: September 29, 2009 (table of contents below)

Web links

- Alan Winston: The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara in Egypt

- Djoser and the Djoser pyramid at www.semataui.de

- Djoser (King, 3rd Dyn) at www.aegyptologie.com

- Saqqara I - Djoser's Step Pyramid (engl.) ( Memento of 29 August 2012 at the Internet Archive )

- Image of a faience tile wall from the south grave (reconstructed)

- Djoser Complex (Engl.)

Individual evidence

- ↑ UNESCO: Advisory Body Evaluation (1979; PDF; 353 kB)

- ↑ a b c Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 131 (The step pyramid of Netjerichet (Djoser))

- ↑ a b Redazione Archaeogate, 18-09-2007: Update on the recent works carried out by the Latvian Scientifique Mission in the Step Pyramid of Saqqara (Egypt) ( Memento from February 23, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Mark Lehner: Secret of the pyramids . Düsseldorf 1997, p. 75 ff. (The royal tombs of Abydos)

- ↑ Mark Lehner: Secret of the pyramids . Düsseldorf 1997, p. 78 ff. (Archaic mastabas in Saqqara)

- ↑ a b c Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 137 f. (The pyramid)

- ↑ Mark Lehner: Secret of the pyramids . Düsseldorf 1997, p. 84 ff. (Djoser's step pyramid complex)

- ^ A b Alan Winston: The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara in Egypt. Part III: The Primary Pyramid Structure.

- ^ Rainer Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world. Mainz 1997, p. 40 ff.

- ↑ R. Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. 3. Edition. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , p. 54 and drawing p. 45.

- ↑ JP Lauer: Histoire Monumentale des Pyramides d'Egypte. Part I: Les Pyramides à Degrés. Cairo 1962, Pl. 10 and 11.

- ↑ R. Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. 3. Edition. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , p. 53.

- ↑ F. Müller-Römer: The construction of the pyramids in ancient Egypt. Utz, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-4069-0 , p. 148 ff.

- ^ Rainer Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world. Mainz 1997, p. 65 ff.

- ↑ Satellite image of the Djoserkomplex on Google Maps

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 133. (The Great Ditch)

- ↑ a b c d e Alan Winston: The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara in Egypt. Part II: The Trench and Perimeter Wall, the South Courtyard, And South Tomb.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 135. (The surrounding wall).

- ↑ statue base JE 49889, Cairo

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 135. (The entrance colonnade)

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 150 f. (The south grave).

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 150 f. (The south courtyard).

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 154 f. (The complex of the Sed festival).

- ^ A b c Alan Winston: The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara in Egypt. Part IV: The South and North Pavilions, The Sed Festival Complex and the Temple “T”.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 153 f. (The temple "T")

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 158 f. (The mortuary temple)

- ^ A b c Alan Winston: The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara in Egypt. Part V: The Mortuary Temple, Serdab, Northern Courtyard and the West Mounds.

- ^ Rainer Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world . von Zabern, Mainz 1997, p. 63 ff.

- ↑ a b Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 159 f. (The Serdab and the northern part of the Djoser complex)

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 156 f. (South house and north house)

- ↑ a b Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Hamburg 1998, p. 160 f. (The Western Massifs)

- ^ Rainer Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world. Mainz 1997, p. 37 ff.

- ^ Andrzej Ćwiek: Mortuary Complex of Netjerykhet - A Re-Evaluation .

- ^ Latvian Expedition ( Memento of February 5, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). On: saqqara.nl , last accessed on March 25, 2014.

- ↑ Summary of the film ( memento of October 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) by Arte with video excerpt

| before | Tallest building in the world | after that |

| (62 m) around 2690 BC BC - around 2600 BC Chr. |

Meidum pyramid |

Coordinates: 29 ° 52 ′ 16.6 ″ N , 31 ° 12 ′ 59 ″ E