Userkaf

| Userkaf | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

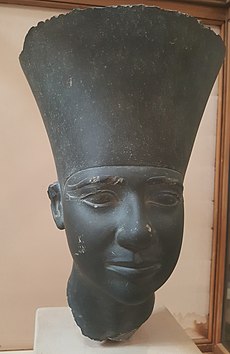

Head of a statue of Userkaf from his solar sanctuary; Egyptian Museum , Cairo

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

JRJ-m3ˁ.t The the Maat realized |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Jrj-m3ˁ.t-nb.tj Who realizes the mate of the two mistresses |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Nfr-bjk-nbw The perfect gold hawk |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

Wsr k3 = f Stronger of his Ka

Wsr k3 = f Stronger of his Ka |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Royal Papyrus Turin (No. 3./17.) |

Proper name: (User) -ka (Wsr) -k3 Das Ka ... (with a name ideogram for a king who represents the Horus falcon) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Abydos (Seti I) (No.26) |

Wsr k3 = f |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Saqqara (No.25) |

Wsr k3 = (f) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Greek after Manetho |

Usercheres |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Userkaf was the first king ( pharaoh ) of the ancient Egyptian 5th dynasty in the Old Kingdom . He ruled roughly between 2500 and 2490 BC. Very little is known about his ancestry, the relationship to the royal family of the previous 4th dynasty and the exact circumstances of the change of dynasty. In the state administration, the first signs of opening the highest state offices to people of non-royal descent can be seen under his rule. Trade relations are documented with Nubia and perhaps also with Greece .

The most important aspect of Userkaf's reign is his construction activity, the central projects of which included a pyramid complex in Saqqara and a solar sanctuary near Abusir . The latter represents the first representative of this type of temple typical of the 5th dynasty and is a testimony to the strong influence of the cult around the sun god Re . Significant remnants of royal statues have been found both in the sun sanctuary and in the pyramid complex, including the head of the oldest known monumental figure from ancient Egypt.

Origin and family

The origin and family relationships of Userkaf are so far only incompletely known. The Egyptian priest and historian Manetho wrote in the 3rd century BC. BC, Userkaf comes from Elephantine on the southern border of Egypt. However, it is unclear whether this tradition is based on facts. After all, he doesn't seem to come directly from the 4th Dynasty royal family .

Key roles in the question of the transition from the 4th to the 5th dynasty play on the one hand a story from the Westcar papyrus , in which Userkaf and his two successors Sahure and Neferirkare are referred to as triplets and sons of a Rudj-Djedet, and on the other hand Chentkaus I was buried in Giza , who is considered the historical model of the literary Rudj-Djedet and the " ancestor " of the 5th dynasty. Chentkaus had a title that is usually translated as "mother of two kings of Upper and Lower Egypt ". Hence, for a long time it was believed that at least two of the first three kings of the 5th Dynasty were actually brothers. However, since none of them is named in Chentkaus' grave and, conversely, Chentkaus is not mentioned in any royal grave complex, there were different opinions about the exact family constellation. For example, it was considered that she was the mother of Userkaf and Neferirkare and the grandmother of Sahure. According to another hypothesis, however, she was seen as the wife of Userkaf and mother of Sahure and Neferirkare.

With the discovery of some new relief blocks from the path of the Sahure pyramid in 2002, the family relationship between the three kings has become a little clearer. On them, Queen Neferhetepes is clearly identified as the mother of Sahure. Userkaf had a small pyramid complex built for them next to his own tomb in Saqqara. So she was his wife and Sahure his son. The position of Neferirkare has also been secured. He was a son of Sahure and his sister wife Meretnebty and thus a grandson of Userkaf.

The exact relationship between Chentkaus I. and Userkaf is still not clear. There is a high probability that she was his mother, but there is only indirect evidence of this. Since she had the title of a “ Queen's Mother ”, but neither the title of a “King's Daughter” nor a “ King's Wife ”, she probably did not come directly from the royal family of the 4th Dynasty or at most from a sideline and was therefore with the last kings of the 4th Dynasty Dynasty - Mykerinos , Shepseskaf and Thamphthis - neither related nor married. Therefore only Userkaf comes into question as her son. Nothing is known about his father and possible siblings.

Domination

Locations of evidence of the Userkaf |

Term of office

The exact duration of the Userkaf's reign is unknown. The Royal Papyrus Turin , which originated in the New Kingdom and is an important document on Egyptian chronology , gives seven years, which began in the 3rd century BC. Living Egyptian priests Manetho 28. The highest contemporary date with certainty is a “3. Times of the count ”, which means the nationwide cattle count, originally introduced as the escort of Horus , for the purpose of tax collection. The fact that these counts initially took place every two years (that is, an “xth year of counting” followed by a “year after the xth time of counting”), but later also take place annually, poses a certain problem (an “xth year of counting” was followed by the “yth year of counting”). Assuming a very short term in office, this fact would not be very significant. More problematic are four dates that were found in the solar sanctuary of Userkaf and a “5th Time of counting ”and a“ year after the 5th time of counting ”. However, since a royal name is not mentioned in these dates, it is still unclear whether they can be attributed to Userkaf or whether they were attached during renovations by a later king, such as Sahure or Neferirkare. Egyptological research tends towards the second possibility with this question and assumes a short reign for Userkaf. Wolfgang Helck , for example, accepted the information in the Turin Papyrus and assumed that the reign was seven years; Jürgen von Beckerath expects eight years.

State administration

Little is known about the administration system under Userkaf. Among high officials, only the vizier Sechemkare can be safely assigned to his reign. He was a son of King Chephren and after Userkaf's death also exercised the office of vizier under his successor Sahure. On the other hand, the dating of the two “chiefs of all labor of the king” Anchchufu and Nianchre is uncertain . The former is dated to the end of the 4th or the beginning of the 5th dynasty, the latter to the beginning of the 5th dynasty. So you could have exercised your office under Userkaf. According to the title successes in their graves, they did not come from the royal family. Although Nianchre carried the title of "King's Son", this was probably more of an honorary title, as he lacked other titles that were typical for biological royal sons.

Religious acts

The worship of the sun god Re , which was an important part of the royal ideology since the middle of the 4th dynasty, reached a new high point under Userkaf with the construction of a sun shrine included in the royal cult of the dead. The fact that religion was also of greater economic importance than in the 4th dynasty becomes clear from the entries in the Palermostein , an important part of the annals stone of the 5th dynasty . While various events are reported there for Userkaf's predecessors - such as military campaigns, the erection of buildings and statue foundations - the entries by Userkaf himself and those of his successors Sahure and Neferirkare consist almost exclusively of land donations and offerings to the large temples. Extensive donations to his solar sanctuary and the temple of Heliopolis are documented for Userkaf , as well as the construction of a shrine in the temple of Buto .

In one of the Fraser graves near Tihna al-Jabal , the owner Nekaanch had an inscription affixed to it stating that his appointment as priest of Hathor was at the instigation of Userkaf.

External relations

Relations to Nubia during Userkaf's reign are documented by seal impressions from Buhen . In addition, there could have been trade relations with Greece . On the island of Kythira between Crete and the Peloponnese , a marble vessel was found in the 1890s on which the name of Userkaf's solar sanctuary is engraved. However, it is unclear whether it reached its place of discovery during Userkaf's rule or only at a later time.

In an entry that is difficult to read, the Palermostein mentions a tribute delivery that was delivered by numerous men in the year after the first count from a location that was not exactly localizable to the pyramid complex of the Userkaf. After a reading of Hartwig Altenmüller it seems at the gifts charms to 303 (?) To have acted Egyptians, who had been banished to the 5th Dynasty during the turmoil of the transition from the 4th and now loyalty vowing from their presumably in southern Palestine located Returned to exile . Their tributes were about 70 Asians, who they handed over as workers to the service of the royal pyramid complex.

Construction activity

The Userkaf pyramid in Saqqara

After his predecessor Schepseskaf had a tomb in the form of a huge mastaba built for himself, Userkaf returned to the shape of the pyramid. He chose the immediate vicinity of the Djoser pyramid in Saqqara as the location . Userkaf's tomb with the ancient Egyptian name "The (cult) sites of Userkaf are pure" has some innovations compared to older pyramids, some of which were taken over by later rulers, but some of which remained unique.

With a side length of 73.30 meters and an original height of 49.40 meters, the Userkaf pyramid was designed to be significantly smaller than its predecessor buildings. The building material for the core masonry was roughly hewn limestone of local origin, while finer Tura limestone was used for the cladding . The entrance to the underground chamber system is no longer in an elevated position on the north side, as in the pyramids of the 4th Dynasty, but in the pavement of the courtyard in front of it. From there, a descending corridor leads down first, which then becomes horizontal. Behind a blocking device there is a branch to the east to a T-shaped magazine chamber. The main course leads south to the antechamber, to the west the actual grave chamber adjoining that in which remains of basalt - sarcophagus was found.

The mortuary temple is much larger in relation to the pyramid than was the case with earlier pyramids. This strong emphasis on the mortuary temple was taken over by Userkaf's successors of the 5th and 6th dynasties , but its position on the south side of the pyramid instead of the east side as usual in the 4th dynasty remained unique. Although the temple was largely destroyed by later construction work, three main sections can be reconstructed: a south-eastern entrance area, a central part that comprised an open pillar courtyard and the Holy of Holies, and a south-western section in which a small cult pyramid stood. Numerous relief fragments and the head of a colossal statue were found in the pillar courtyard. The pyramid and the mortuary temple are surrounded by an enclosure wall, the valley temple and the path that connected it with the mortuary temple have not yet been excavated.

The Queen's Pyramid of Neferhetepes in Saqqara

South of the mortuary temple is the pyramid of Neferhetepes, a queen pyramid, which has its own pyramid complex separated from the tomb of Userkaf. It was originally built as a three-tier structure with a cladding of white limestone blocks. The underground chamber system consists of an antechamber and a burial chamber, both of which were provided with a gable roof. On the east side of the pyramid is a heavily damaged mortuary temple, which was probably designed similarly to that of the king's pyramid and had a central courtyard surrounded by pillars, a sacrificial hall, statue niches and storage rooms.

The sun sanctuary of Userkaf in Abusir

In Abusir , Userkaf built a solar sanctuary called the “Fortress of Re”. It represents the first example of this type of temple and is, besides the solar sanctuary of Niuserre, the only surviving of the total of six known solar sanctuaries of the 5th dynasty. The facility was excavated in the 1950s under the direction of Herbert Ricke . This sanctuary has a valley temple with an antechamber, a central part, a courtyard surrounded by pillars and seven niches. In a south-westerly direction, a wide path leads to the actual sanctuary. Ricke was able to determine that this had been built in several construction phases. In its final state, it had a central monumental pedestal on which an obelisk made of granite stand. To the east of the pedestal was an altar and a statue shrine to either side. The sanctuary is surrounded by a wall, on the southern outside of which there is an outbuilding.

After evaluating contemporary written sources, the striking obelisk appears to have been created in a later construction phase by one of Userkaf's successors, either Sahure or Neferirkare. In texts from Userkaf's reign, the name of the solar sanctuary was always written with a determinative (Deutzeichen), which suggests that in the place of the later obelisk there was only a wooden pillar crowned with a sun disk.

The temple of et death

The oldest traces of the Temple of the Month in et-Tod go back to Userkaf. Due to numerous alterations from the Middle Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period, as well as the severe degree of destruction of the temple structure, very little of the Userkaf complex has been preserved. All that can be reconstructed is that he had a small brick temple built, which also included a granite pillar bearing the king's name.

Statues

Statues of Userkaf have so far been found in two places: In the valley temple of his solar sanctuary (see picture above) in Abusir and in the mortuary temple of his pyramid in Saqqara. None of the statues is completely preserved; the most outstanding examples are two well-preserved statue heads.

One of them was discovered in the 1950s during excavations outside the valley temple of the Userkaf sanctuary and is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (inv.no. JE 90220). It is made of greywacke and measures 45 × 26 × 25 cm. The king is depicted beardless and wears the red crown of Lower Egypt on his head . The excavator Herbert Ricke originally assumed that it was a portrait of the goddess Neith , who was also depicted in this way. Later, however, remnants of a mustache painted with black paint were found, which clearly confirmed that it was a statue of a king.

Other statuary finds from the Userkaf sanctuary are smaller fragments of limestone , granite and red sandstone , which were discovered by Ludwig Borchardt in 1907. Another piece of alabaster originally belonged to an almost life-size statue. It shows the king's mouth and chin and is now in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin (Inv.-No. ÄM 19774)

Another very well-preserved statue head was found in 1928 by Cecil Firth in the mortuary temple of the Userkaf pyramid and is now also in the possession of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (inv. No. JE 52501). The head is made of rose granite and is 75 cm high. It originally belonged to a colossal statue about four meters high (based on the assumption that it was a seated statue) and thus, apart from the Great Sphinx of Giza, to the largest known statue of ancient Egypt to date. The king is also depicted here without a beard and wearing the Nemes headscarf with a uraeus snake on his forehead. Also in the mortuary temple of the pyramid, further statue fragments made of granite and diorite were found, which bear the proper name and Horus name Userkaf.

Another piece is of unknown origin, possibly depicting Userkaf. It is now in the Cleveland Museum of Art (Inv.-No. 1979.2). It is the head of a limestone statue and shows the king with a ceremonial beard and the white crown of Upper Egypt. It has a height of 17.2 cm, a width of 6.5 cm and a depth of 7.2 cm. There are remains of painting on the face.

Head of a colossal statue of Userkaf, Egyptian Museum Cairo (JE 52501, copy in the University of Lausanne )

Userkaf in memory of ancient Egypt

Userkaf enjoyed a high reputation for a long time in the further course of Egyptian history . His cultic veneration did not last very long and his buildings were left to decay. During the Middle Kingdom , at the beginning of the 12th dynasty , King Amenemhet I had parts of Userkaf's pyramid complex torn down and used the stones to build his own pyramid in El Lisht .

Probably also in the Middle Kingdom, Userkaf was first mentioned in a literary work, namely in one of the stories in the Westcar papyrus . The majority of the stories assume the 12th dynasty as the time of origin, although there are now increasing arguments to date them to the 17th dynasty , from which the traditional papyrus also comes. The action takes place at the royal court and revolves around Pharaoh Cheops from the 4th dynasty as the main character. In order to pass the boredom, he lets his sons tell wonderful stories. After three of his sons have already told him about past miracles, the fourth Hordjedef finally has a still living magician called Djedi brought in, who first performs magic tricks. Cheops then wanted to know from Djedi whether he knew the number of jpwt (exact meaning of the word unclear, translated as locks, chambers, boxes) in the Thoth sanctuary of Heliopolis . Djedi denies and explains that Rudj-Djedet, the wife of a Re- priest, will give birth to three sons who will ascend the royal throne. The oldest of these is to find out the number and convey it to Cheops. Djedi adds reassuringly that these three will only ascend to the throne when Cheops' son and grandson have ruled. Cheops then decides to go to the home of the Rudj-Djedet. Then suddenly the description of the birth of the three kings follows. The four goddesses Isis , Nephthys , Meschenet and Heket and the god Khnum appear and are led to the woman giving birth by Rauser, Rudj-Djedets husband. Through dance and magic they help the three kings into the world. Their names are shown here as User-Re-ef, Sah-Re and Keku, so these are the first three kings of the 5th dynasty: Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai.

A relief fragment is known from the New Kingdom , which comes from the grave of a priest named Mehu from Saqqara and dates to the 19th or 20th dynasty . Three deities are depicted on it, facing a number of deceased kings. These are Djoser and Djos erti from the 3rd dynasty and Userkaf from the 5th dynasty. Only a badly damaged signature remains of a fourth king, which was read partly as Schepseskare and partly as Djedkare . The relief is an expression of the personal piety of the tomb owner, who made the ancient kings pray to the gods for him.

During the 19th Dynasty, Chaemwaset , a son of Ramses II , carried out restoration projects across the country. This also included numerous pyramids, as is known from inscriptions. Possibly the Userkaf pyramid was one of them, because remains of a hieroglyphic inscription were also found on the fragments of its cladding .

literature

General

- Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs, Volume I: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, Oakville 2008, ISBN 978-0-9774094-4-0 , pp. 484-486.

- Peter A. Clayton The Pharaohs . Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1999, ISBN 3-8289-0661-3 , pp. 31, 59-61.

- Martin von Falck, Susanne Martinssen-von Falck: The great pharaohs. From the early days to the Middle Kingdom. Marix, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-7374-0976-6 , pp. 122–127.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 304-305.

About the name

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Handbook of the Egyptian king names . 2nd edition, von Zabern, Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-422-00832-2 , pp. 56-57.

To the pyramid

- Zahi Hawass (Ed.): The Treasures of the Pyramids . Weltbild, Augsburg 2003, ISBN 3-8289-0809-8 , pp. 238-239.

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids . Orbis, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-572-01039-X , pp. 140-141.

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , pp. 159-164.

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 306-313.

For further literature on the pyramid see under Userkaf pyramid

To the sun sanctuary

- Miroslav Verner: The Sun Sanctuaries of the 5th Dynasty . In: Sokar No. 10 , 2005, pp. 39-41.

- Herbert Ricke et al .: The sun sanctuary of King Userkaf . Contributions to Egyptian building research and antiquity. Volumes 7 and 8, Wiesbaden 1965 and 1969.

- Susanne Voss: Investigations into the sun sanctuaries of the 5th dynasty. Significance and function of a singular temple type in the Old Kingdom. Hamburg 2004 (also: Dissertation, University of Hamburg 2000), pp. 7–59, ( PDF; 2.5 MB ).

For further literature on the solar sanctuary see under Userkaf's solar sanctuary

Questions of detail

- Hartwig Altenmüller: The "taxes" from the 2nd year of the Userkaf. In: Dieter Kessler, Regine Schulz (ed.): Commemorative publication for Winfried Barta (= Munich Egyptological investigations. Volume 4). Munich 1995, pp. 37-48 ( online ).

- Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronology of the pharaonic Egypt . von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 , pp. 153-155, 174-175.

- Vinzenz Brinkmann (Ed.): Sahure. Death and life of a great pharaoh. Hirmer, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-7774-2861-1 .

- Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3 , pp. 62-69 ( PDF file; 67.9 MB ); retrieved from the Internet Archive .

- Miroslav Verner : Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology . In: Archives Orientální. Vol. 69 , Prague 2001, pp. 363-418 ( PDF; 31 MB ).

Web links

Notes and individual references

- ^ Alan H. Gardiner: The royal canon of Turin . Panel 2; The presentation of the entry in the Turin papyrus, which differs from the usual syntax for hieroboxes, is based on the fact that open cartridges were used in the hieratic . The alternating time-missing-time presence of certain name elements is due to material damage in the papyrus.

- ↑ Year numbers according to Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs .

- ↑ Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho, introduced and translated. Native traditions in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor (Michigan) 2000, ISBN 0-472-08687-1 , p. 135.

- ↑ Silke Roth: The royal mothers of ancient Egypt from the early days to the end of the 12th Dynasty (= Egypt and Old Testament. Volume 46). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04368-7 , pp. 90-99.

- ^ Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London 2004, pp. 62, 64-65, 68.

- ↑ Tarek El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. New evidence. In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Prague 2006, pp. 192–198.

- ↑ Tarek El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. New evidence. In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Prague 2006, pp. 198–213.

- ↑ Hartwig Altenmüller: The position of the king mother Chentkaus in the transition from the 4th to the 5th dynasty. In: Chronique d'Égypte. Volume 45, 1970, pp. 223-235 ( online )

- ↑ Silke Roth: The royal mothers of ancient Egypt from the early days to the end of the 12th Dynasty (= Egypt and Old Testament. Volume 46). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04368-7 , pp. 90-93.

- ↑ see Verner: Archaeological Remarks .

- ^ Verner: Archaeological Remarks . Pp. 386-390

- ^ Verner: Archaeological Remarks . P. 390

- ↑ Werner Kaiser: To the sun sanctuaries of the 5th dynasty . In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department . Vol. 14, Mainz 1956, p. 108

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: History of ancient Egypt (= Handbook of Oriental Studies. Dept. 1: The Near and Middle East. Volume 1). Brill, Leiden / Cologne 1981, p. 75, ( online version ).

- ↑ Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1994, p. 155.

- ^ Nigel Strudwick: The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom. Routledge, Boston 1985, ISBN 0-7103-0107-3 ( PDF; 21 MB ), p. 136.

- ^ Nigel Strudwick: The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom. Routledge, Boston 1985, ISBN 0-7103-0107-3 ( PDF; 21 MB ), pp. 79, 102-103.

- ↑ Michel Baud: Under the rule of the sun. Myth and worship of the great God. In: Vinzenz Brinkmann (ed.): Sahure. Death and life of a great pharaoh. Hirmer, Munich 2010, p. 37.

- ↑ James Henry Breasted: Ancient records of Egypt. Historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I: The first to seventeenth dynasties. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1906, § 153–158 ( PDF; 12.0 MB ).

- ↑ James Henry Breasted: Ancient records of Egypt. Historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I: The first to seventeenth dynasties. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1906, § 219 ( PDF; 12.0 MB ).

- ↑ Kurt Sethe : An Egyptian monument of the Old Kingdom from the island of Kythera with the name of the sun sanctuary of the Userkef . In: Georg Steindorff (Hrsg.): Journal for Egyptian language and antiquity . Fifty-third volume. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1917, p. 55–58 ( digitized version [accessed April 13, 2016]).

- ^ Arthur Evans: Further Discoveries of Cretan and Aegean Script: With Libyan and Proto-Egyptian Comparsions. In: Journal of Hellenic Studies. Vol. 17, 1897, pp. 349-350.

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 305.

- ↑ Hartwig Altenmüller: The "taxes" from the 2nd year of the Userkaf. In: Dieter Kessler, Regine Schulz (ed.): Commemorative publication for Winfried Barta (= Munich Egyptological investigations. Volume 4). Munich 1995, pp. 37-48 ( online ).

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1998, pp. 308-309.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1998, pp. 309-311.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1998, p. 311.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The sun shrines of the 5th Dynasty. In: Sokar. Volume 10, 2005, pp. 39-41.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The sun shrines of the 5th Dynasty. In: Sokar. Volume 10, 2005, p. 41.

- ↑ Dieter Arnold: The temples of Egypt. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1996, ISBN 3-86047-215-1 , p. 107.

- ^ Richard H. Wilkinson: The world of temples in ancient Egypt. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-18652-4 , pp. 200-201.

- ↑ Rainer Stadelmann: The head of the Userkaf in the "valley temple" of the solar sanctuary in Abusir . In: Sokar, No. 15, 2007, pp. 56-61.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The sun shrines of the 5th Dynasty . In: Sokar, No. 10, 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. III. Memphis . 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1974, p. 333; Rainer Stadelmann: The head of the Userkaf in the "valley temple" of the solar sanctuary in Abusir . In: Sokar, No. 15, 2007, p. 60.

- ↑ Christiane Ziegler (Ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids . The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, pp. 314-315.

- ^ The Cleveland Museum of Art - Head of King Userkaf, c. 2454-2447 BC .

- ^ Adela Oppenheim: Cast of a Block with Running Troops and an Inscription with the Names and Titles of King Userkaf. In: Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, ISBN 0-87099-906-0 , pp. 318-319.

- ↑ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom . LIT Verlag, Münster / Hamburg / London 2003, p. 178

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung : The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Part I. Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties . Munich Egyptological Studies, Vol. 17, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin, 1969, pp. 74–76

- ↑ Verner: The pyramids . P. 308

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

|

Thamphthis ? Chentkaus I. ? |

Pharaoh of Egypt 5th Dynasty (beginning) |

Sahure |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Userkaf |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Egyptian king (pharaoh) of the 5th dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 26th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 25th century BC Chr. |