Sahure

| Name of sahure | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sahures statue (detail); Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York City

|

||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

Nb-ḫˁw Lord of the Crowns / Lord of the Coronation Figure |

|||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Nb-ḫˁw Lord of the Crowns / Lord of the Coronation Figure |

|||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Bjkwj-nbw Gold (golden) of the two falcons |

|||||||||||||

| Proper name |

(Sahu Re) S3ḥw Rˁ Re comes to me |

|||||||||||||

| List of kings of Abydos (Seti I) (No.27) |

S3ḥw Rˁ |

|||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Saqqara (No.26) |

S3ḥw Rˁ |

|||||||||||||

|

Greek for Manetho |

Sephres |

|||||||||||||

Sahure was the second king ( pharaoh ) of the ancient Egyptian 5th dynasty in the Old Kingdom . He ruled approximately within the period from 2490 to 2475 BC. In the state administration he continued the policy of his predecessors to increasingly fill high state offices with people who did not come from the royal family. In terms of foreign policy, archaeological finds and relief representations attest to trade relations with the Middle East , Nubia and Punt as well as war campaigns on the Sinai Peninsula and perhaps also to Libya . But Sahure is best known for his building activity, whose central projects included a pyramid complex , a previously undiscovered solar sanctuary and a palace complex. The mortuary temple of its pyramid is one of the best preserved in Egyptian history . Architecturally, it represented a formative model for later temple complexes. Its well-preserved relief representations give detailed insights into the family relationships of the 5th dynasty as well as into the economy, administration and external relations of Egypt during Sahure's reign.

Origin and family

Sahure's family relationships were unclear for a long time and research on this was mainly based on the information in the Westcar papyrus , according to which the first three kings of the 5th dynasty ( Userkaf , Sahure and Neferirkare ) were brothers. According to another variant Sahure and Neferirkare were as sons of Userkaf and Chentkaus I. considered.

Only in 2002 newly discovered relief blocks from the path of the Sahure pyramid could clarify this. Accordingly, Sahure's mother was the " daughter of God ", " king consort " and " king mother " Neferhetepes . She was the wife of Userkaf , who had a queen pyramid built for her in Saqqara next to his own pyramid complex. Userkaf can therefore be seen as the father of Sahure.

Meretnebty appears on the same row of pads as the wife of the Sahure . She may have been the ruler's full sister, but this can only be deduced from a scene that shows the king's mother and queen hand in hand. However, there is no other evidence, such as titles that identify her as a king's daughter.

Several of the king's sons are known. Two of them are called the eldest sons of the king. They are Ranefer, who would later ascend the throne under the name Neferirkare , and Netjerirenre . Since both had the title of eldest prince, but only one known consort of Sahure, they could possibly have been twins. Other sons of Sahure were Chakare , Raemsaf and Heryemsaf .

Domination

Sites of evidence of the Sahure |

Term of office

In contrast to many other rulers of the Old Kingdom, the period of reign of the Sahure can be specified quite precisely because of the comparatively good sources. It lasted about 12 to 13 years, which is evident from both contemporary sources and from texts written much later. The royal papyrus Turin , which originated in the New Kingdom and is an important document on Egyptian chronology , states 12 years, which began in the 3rd century BC. Living Egyptian priests Manetho 13. The highest contemporary date with certainty is a "year after the 6th (or 7th?) Time of the count", which means the nationwide cattle count, originally introduced as the escort of Horus , for the purpose of tax collection. The fact that these counts initially took place every two years (that is, an “xth year of counting” was followed by a “year after the xth time of counting”) poses a certain problem with dates from the Old Kingdom could sometimes also take place annually (an “xth year of counting” was followed by the “yth year of counting”). With Sahure, this uncertainty factor is greatly minimized. There are dates for a total of four "years of the count" and three "years after the count". It can therefore be assumed that there was an essentially regular biennial count under Sahure's rule.

The only major problem is a date that Ludwig Borchardt discovered at the beginning of the 20th century in the pyramid complex of the Sahure and which calls a "year 12", which, taking into account a biennial count, would mean a doubling of Sahure's reign. A detailed scientific examination of this inscription was prevented by the fact that Borchardt did not note where he had discovered it and neither made a drawing nor a photo. It is therefore very likely that the inscription was only added after Sahure's reign. It could come from restoration work by later kings or it could have been added as a so-called visitor inscription in the valley temple of the pyramid in the New Kingdom .

State administration

At least two viziers were at the head of the state administration : Sechemkare and Werbauba , perhaps also Waschptah-Isi and Minnefer . Except for Sechemkare, none of these officials seem to come from the royal family, so Sahure continued the policy pursued since the beginning of the 5th dynasty of increasingly filling high state offices with non-noble people.

Religious acts

An important document that reports on events from Sahure's reign is the Palermo Stone , which is considered an important part of the Annals Stone of the 5th Dynasty . He particularly goes into the religious activities of Sahure and names extensive sacrificial and land foundations for various deities, as well as the production of boats and statues.

Trade and expeditions

The Palermostein calls for the last year of Sahure's reign the arrival of trade goods from the country Punt , which implies that an expedition was sent there. Further trade relations are attested with the Near East . An alabaster vessel was found in Byblos . The trade relations in this region are also underlined by a relief in the mortuary temple of the Sahure pyramid, on which ships are depicted whose crews are Syrians . Furthermore, seal impressions from boos and a graffito in Tom's document connections to Nubia . Two expeditions have been handed down through inscriptions: one led to the diorite quarries near Abu Simbel , another to the gold mines of Wadi al-Gidami in the eastern desert.

Campaigns

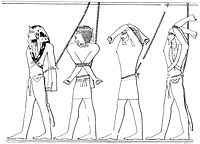

The only campaign that can be reliably proven during Sahure's reign was a raid against Bedouins on the Sinai Peninsula . The king had this reported on a large relief in Wadi Maghara , which is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo . A possible second campaign was directed against Libya . Reliefs from the ascent of the Sahure pyramid, in which processions of captured Asians and Libyans are shown, testify to this. However, since an almost identical image was also found in the pyramid complex of Pepi II , it is unclear whether a real historical event is really represented or rather a purely symbolic beating of the enemies of Egypt , which had to be repeated by each new king.

Construction activity

A total of three royal building projects are known from Sahure's reign, of which only his pyramid complex has been archaeologically researched so far. Like his predecessor Userkaf, Sahure also built a solar sanctuary, which is only known from written sources. The second so far undiscovered structure is Sahure's palace complex.

The Sahure pyramid in Abusir

→ Main article: Sahure pyramid

Sahure chose Abusir as the location for his pyramid and thus founded a new royal necropolis not far from the solar sanctuary of Userkaf . The pyramid had the ancient Egyptian name "The soul of the Sahure appears" and is today badly damaged. With a side length of 78.8 meters and an original height of 47.3 meters, it was quite similar in size to the Userkaf's grave. The building material for the core masonry was roughly hewn limestone of local origin; Finer limestone from Ma'asara on the opposite bank of the Nile was used for the cladding .

The entrance to the underground chamber system is located directly above the base of the north wall. The chamber system itself is designed to be comparatively simple. First a short descending corridor leads to a vestibule with a locking device. Behind it, a slightly ascending corridor runs further south to the antechamber, to which the actual burial chamber adjoins to the west, in which remains of a basalt sarcophagus were found.

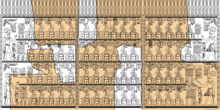

In contrast to the actual pyramid, the associated temple complex is very well preserved. The valley temple , which is quite simply designed, has two entrances: one in the south and one in the east. Both are provided with columns and lead into a small room with two more columns. From here the access leads to the west, which connects the valley with the mortuary temple. Numerous reliefs come from the pathway, showing, among other things, the king in the form of a sphinx .

The mortuary temple is divided into two areas. The outer, public part consists of an elongated entrance hall and a courtyard surrounded by columns, around which a corridor runs. Behind the courtyard is a transverse corridor that separates the outer from the intimate part of the temple. The entrance to the five-niche chapel is in the middle of the corridor, with storage rooms to the side. The entrance to the sacrificial hall branches off from the five-niche chapel. At the southern end of the cross corridor there is an entrance to the cult pyramid. The mortuary temple and the royal pyramid were enclosed by a wall, the cult pyramid also had its own enclosure.

When building his valley temple, Sahure based himself on previous buildings, but introduced numerous innovations. So he chose palm frond columns for the courtyards and entrance colonnades instead of the pillars previously used. The room scheme established by him, the building materials chosen and above all the relief themes were taken up by his successors to a large extent. A large part of the well-preserved reliefs from the mortuary temple came to the Egyptian Museum in Berlin after Ludwig Borchardt's excavations at the beginning of the 20th century .

The solar sanctuary of the Sahure

→ Main article: Sun sanctuary of the Sahure

Like Userkaf, Sahure built a solar sanctuary which was named “Field of Re” and, according to written sources, apparently remained unfinished. It has not yet been found, but archaeological finds such as the remains of an obelisk suggest that it may have been in Abusir in the vicinity of the Niuserre pyramid .

The palace of the sahure

Sahure's palace complex was called "Who exalts the beauty of the Sahure". It has not yet been proven archaeologically, but only known from relief scenes and administrative texts. Vessel labels from the mortuary temple of the Raneferef pyramid prove that the palace had a slaughterhouse which, after Sahure's death, was responsible for the maintenance of the death cult of his successors. Several events that took place in this palace are known from relief blocks. This includes the return of an expedition from Punt, the planting of a frankincense tree brought from there and the awards of officials. From all this evidence it can be concluded that the structure was located near a port facility and near the mortuary temple of Abusir. The most likely location is therefore an area between the mortuary temples of the Sahure and the Niuserre , the former lake of Abusir and the Bahr el-Lebeini (the "Great Canal of Memphis").

Statues

Only a few fragments of statues and sphinxes were discovered in Sahure's pyramid complex . These consisted of alabaster , slate and sandstone and are now partly in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin . The only nearly completely preserved image of the Sahure is a statue of unknown origin, which is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York . It is made of gneiss and measures 64 × 46 × 41.5 cm. The statue has a wide base and a back plate. The left side is occupied by the enthroned king, on his right is the personification of the fifth Upper Egyptian Gau . Both figures are connected to the back plate. The king is dressed in an apron and wears the Nemes headscarf on his head and an artificial beard on his chin. His own name and Horus name are engraved to the right and left of his legs . The statue appears to have originally been planned for Chephren , a ruler of the 4th Dynasty. Stylistic subtleties, such as the facial features, however, suggest that it was not simply usurped by Sahure , but that it remained unfinished and was later completed with Sahure's features. In 2015 a fragment of a Sahure statue was found in Elkab .

Sahure in the memory of ancient Egypt

Old empire

Sahure enjoyed a high reputation for a long time in the further course of Egyptian history. For his cult of the dead 22 agricultural goods ( domains ) were set up, which ensured the supply of offerings . In addition, numerous graves of priests are known from Abusir and Saqqara, who served in the death cult of the king during the 5th and 6th dynasties .

Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period

During the Middle Kingdom , at the beginning of the 12th dynasty , King Sesostris I had a statue of Sahure erected in the temple of Karnak , which was probably part of a group of images of deceased kings. The piece is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (Inv.No. CG 42004). It is made of black granite and is 50 cm high. The king is depicted enthroned and wears a pleated apron and a round curly wig. Both sides of the throne bear inscriptions that identify the work as a portrait of Sahure, which was commissioned by Sesostris I.

Probably also in the Middle Kingdom, Sahure was first mentioned in a literary work, namely in one of the stories in the Westcar papyrus . The majority of the stories assume the 12th dynasty as the time of origin, although there are now increasing arguments to date them to the 17th dynasty , from which the traditional papyrus also comes. The action takes place at the royal court and revolves around Pharaoh Cheops from the 4th dynasty as the main character. In order to pass the boredom, he lets his sons tell wonderful stories. After three of his sons have already told him about past miracles, the fourth Hordjedef finally has a still living magician called Djedi brought in, who first performs magic tricks. Cheops then wanted to know from Djedi whether he knew the number of jpwt (exact meaning of the word unclear, among other things translated as locks, chambers, boxes) of the Thoth sanctuary of Heliopolis . Djedi denies and explains that Rudj-Djedet, the wife of a Re- priest, will give birth to three sons who will ascend the royal throne. The oldest of these is to find out the number and convey it to Cheops. Djedi adds reassuringly that these three will only ascend to the throne when Cheops' son and grandson have ruled. Cheops then decides to go to the home of the Rudj-Djedet. Then suddenly the description of the birth of the three kings follows. The four goddesses Isis , Nephthys , Meschenet and Heket and the god Khnum appear and are led to the woman giving birth by Rauser, Rudj-Djedets husband. Through dance and magic they help the three kings into the world. Their names are shown here as User-Re-ef, Sah-Re and Keku, so these are the first three kings of the 5th dynasty: Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai.

New Kingdom, Late Period, and Ptolemaic Period

During the New Kingdom was in the 18th Dynasty under Thutmose III. In the Karnak Temple the so-called King List of Karnak is attached, in which the name Sahure appears. In contrast to other ancient Egyptian king lists, this is not a complete listing of all rulers, but a shortlist that only names the kings for which during the reign of Thutmose III. Sacrifices were made. Since there is presumably a connection between this list and the statues of kings that have been erected in Karnak since the Middle Kingdom, it can be assumed that Sahure's cult of the dead continued to exist in both the Middle and New Kingdoms.

In the 19th dynasty , Chaemwaset , a son of Ramses II , carried out restoration projects across the country. This also included numerous pyramids, including that of the Sahure, as is known from inscriptions on facing stones.

During the New Kingdom and far beyond, the mortuary temple of the Sahure pyramid was a much-visited sanctuary. As shown by square nets on several reliefs, these served as templates for other building projects. Since the 18th dynasty, a cult of the lion goddess Sachmet can also be traced in the pyramid temple. It began under Thutmose III at the latest. During the 18th and 19th dynasties, numerous visitor inscriptions, steles and statues were left in the temple. There are also testimonies from the 26th dynasty . The most recent are from the Ptolemaic period .

literature

General

- Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs, Volume I: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, Oakville 2008, ISBN 978-0-9774094-4-0 , pp. 343-345.

- Martin von Falck, Susanne Martinssen-von Falck: The great pharaohs. From the early days to the Middle Kingdom. Marix, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3737409766 , pp. 127-133.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 243-244.

- Vinzenz Brinkmann (Ed.): Sahure. Death and life of a great pharaoh. Hirmer, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-7774-2861-1 .

About the name

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Handbook of the Egyptian king names . 2nd edition, Zabern, Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-422-00832-2 , pp. 56-57.

To the pyramid

- Ludwig Borchardt : The grave monument of King Sahure . 2 volumes, JC Hinrichs, Leipzig 1910–13 (the pyramid excavation publication; online version ).

- Zahi Hawass (Ed.): The Treasures of the Pyramids . Weltbild, Augsburg 2003, ISBN 3-8289-0809-8 , pp. 224-230.

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids . Orbis, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-572-01039-X , pp. 242-245.

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , pp. 164-171.

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 313-324.

For further literature on the pyramid see under Sahure pyramid

To the sun sanctuary

- Miroslav Verner: The Sun Sanctuaries of the 5th Dynasty . In: Sokar, No. 10 , 2005, pp. 42-43.

- Susanne Voss: Investigations into the sun sanctuaries of the 5th dynasty. Significance and function of a singular temple type in the Old Kingdom. Hamburg 2004 (also: Dissertation, University of Hamburg 2000), pp. 135–139, ( PDF; 2.5 MB ).

Questions of detail

- Tarek El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. New evidence . In: Miroslav Bárta; Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, Prague 2006, ISBN 80-7308-116-4 , pp. 191-218.

- Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronology of the pharaonic Egypt . Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 , pp. 153-155.

- Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt . The American University in Cairo Press, London 2004, ISBN 977-424-878-3 , pp. 62-69.

- Miroslav Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology . In: Archives Orientální. Vol. 69, Prague 2001, pp. 363-418 ( PDF; 31 MB ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Sahure in the catalog of the German National Library

- Look at Digital Egypt

- The Ancient Egypt Site

- Alina Schadwinkel: At the grave of the sun son. In: The time. 24/2010 of June 10, 2010, p. 35.

- Sahure. Death and Life of a Great Pharaoh - Exhibition in the Liebieghaus, Frankfurt am Main

Individual evidence

- ↑ Year numbers according to T. Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Düsseldorf 2002.

- ^ Aidan Dodson, Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt . The American University in Cairo Press, London 2004, pp. 64-65.

- ↑ Tarek El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. New evidence. In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Prague 2006, pp. 192–198.

- ↑ Tarek El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. New evidence. In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Prague 2006, pp. 198–203.

- ↑ Tarek El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. New evidence. In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Prague 2006, pp. 208–213.

- ↑ Tarek El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. New evidence. In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Prague 2006, pp. 213–214.

- ↑ Tarek El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. New evidence. In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Prague 2006, pp. 214–216.

- ↑ see M. Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology .

- ^ M. Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology . P. 391.

- ^ M. Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology . Pp. 392-393.

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 244.

- ^ Nigel Strudwick: The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom. Routledge, Boston 1985, ISBN 0-7103-0107-3 ( PDF; 21 MB ), pp. 301, 308.

- ↑ a b T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 243.

- ↑ Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs, Volume I. Bannerstone Press, Oakville 2008, p. 345.

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, pp. 243-244.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck : History of ancient Egypt . Handbuch des Orients I 1/3, Leiden 1981, p. 65 ( online version )

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1998, pp. 316-317.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1998, pp. 317-318.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1998, pp. 323-324.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1998, pp. 318-323.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1998, p. 313.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: The Berlin reliefs from the pyramid complex of the Sahure. In: Vinzenz Brinkmann (ed.): Sahure. Death and life of a great pharaoh. Hirmer, Munich 2010, pp. 183–194.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The sun shrines of the 5th Dynasty . In: Sokar, No. 10, 2005, pp. 42-43

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: reflections on the royal palaces of the Old Kingdom. In: Sokar. Volume 24, 2012, pp. 16-19.

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. III. Memphis . 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1974, p. 333

- ↑ Christiane Ziegler (Ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids . The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, pp. 328-330

- ^ Past Preserves News . On: pastpreserversnews.tumblr.com from April 28, 2015.

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 244.

- ↑ a b Dietrich Wildung: The afterlife of the Sahure. In: Vinzenz Brinkmann (ed.): Sahure. Death and life of a great pharaoh. Hirmer, Munich 2010, p. 276.

- ↑ a b Dietrich Wildung : The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Part I. Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties . Munich Egyptological Studies, Vol. 17, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin, 1969, pp. 60–63.

- ^ Georges Legrain: Catalog général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire. CG 42001-42138: Statues et statuettes de rois et de particuliers. Cairo 1906, pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I. Old and Middle Kingdom (= introductions and source texts for Egyptology. Vol. 1). LIT, Münster / Hamburg / London 2003, ISBN 978-3-8258-6132-2 , p. 178.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung : The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Part I. Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties . Munich Egyptological Studies, Vol. 17, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin, 1969, p. 170

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: The afterlife of the Sahure. In: Vinzenz Brinkmann (ed.): Sahure. Death and life of a great pharaoh. Hirmer, Munich 2010, p. 275.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung : The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Part I. Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties . Munich Egyptological Studies, Vol. 17, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin, 1969, p. 198

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: The afterlife of the Sahure. In: Vinzenz Brinkmann (ed.): Sahure. Death and life of a great pharaoh. Hirmer, Munich 2010, pp. 275-276.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Userkaf |

Pharaoh of Egypt 5th Dynasty |

Neferirkare |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sahure |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Neb-chau, Sephres |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Egyptian king of the 5th dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 25th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 2475 BC Chr. |