Pepi II.

| Name of Pepi II. | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Statue of Pepis II as a child on the lap of his mother Anchenespepi II; Brooklyn Museum , New York City

|

||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

Nṯr.j-ḫˁ.w Divine in apparitions |

|||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Nṯr.j-ḫˁ-nb.tj Divine in apparitions of the two mistresses |

|||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Sechem Bjk.-nbw-sḫm Mighty Goldfalke |

|||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Nfr-k3-Rˁ With perfect Ka des Re |

|||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

Pjpj Pepi |

|||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Abydos (Seti I) (No.38) |

Nfr-k3-Rˁ |

|||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Saqqara (No.36) |

Nfr-k3-Rˁ |

|||||||||||||||

|

Greek for Manetho |

Phiops |

|||||||||||||||

Pepi II ( Greek Phiops II ) was the fifth king ( pharaoh ) of the ancient Egyptian 6th dynasty in the Old Kingdom . He ruled approximately within the period from 2245 to 2180 BC. And came to the throne as a child. With probably more than 60 years of reign, his reign was one of the longest in the history of ancient Egypt.

In the state administration under Pepi II a continuation of the long-lasting decentralization as well as a growth of the civil service can be observed. In a complex interplay with unfavorable climatic changes, this increase in the number of civil servants seems to have contributed to a scarcity of resources in the advanced course of his government, which ultimately led to the collapse of the Old Kingdom under his successors. Intensive trade contacts to Byblos as well as to Nubia and Punt have been handed down through grave inscriptions and archaeological finds . The contacts to the south were made increasingly difficult by hostilities with Bedouin tribes and strengthened Nubian principalities. The most important building project of Pepis II is his pyramid complex in the south of Saqqara .

Origin and family

Pepi II was the son of Pharaoh Pepi I and his wife Anchenespepi II (also called Anchenesmerire II). His half-brothers were his predecessor Merenre and the two princes Tetianch and Hornetjerichet . His half-sisters Neith and Iput II and his niece Anchenespepi III are wives . as well as two other women named Anchenespepi IV. and Wedjebten . From the marriage with Neith Pepis heir to the throne Nemtiemsaef II. (Antiemsaef II.) Emerged, from the marriage with Anchenespepi IV. The future king Neferkare Nebi . In Nebkauhor-Idu and Ptahschepses then possibly to other sons of Pepi II. Apart from Neferkare Nebi an intimate relationship with the many very short reigning kings is the eighth dynasty unclear.

Domination

Term of office

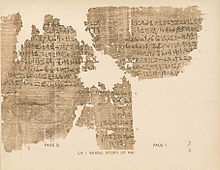

Although there is agreement among Egyptologists that the reign of Pepis II was very long, its exact duration is still controversial. In the Royal Papyrus Turin from the New Kingdom , 90 years are given in its badly damaged entry (possibly also 93 or 94). In the 3rd century BC Egyptian priest Manetho living in BC apparently referred to this and stated that Pepi II came to the throne at the age of six and died at the age of 100, resulting in 94 years of reign.

Despite this extraordinary length (for comparison: the reign of Sobhuza II of Swaziland , the longest documented term of office of a head of state, lasted “only” 82 years), the information provided by Manethus and the Turin papyrus has recently been viewed as plausible by some researchers , for example by Wolfgang Helck or Erik Hornung .

Hans Goedicke expressed doubts about this, considering the information in the Turin papyrus as a prescription from "60" to "90". The contemporary dates seem to support this interpretation. Goedicke saw a graffito in the mortuary temple of the Pepi II pyramid as an indication of Pepi's year of death. It was about the indication of a "year of the 31st time of the count ". This refers to the nationwide cattle count, originally introduced as the escort of Horus , for the purpose of tax collection. This census originally took place every two years (that is, an “xth year of counting” was followed by a “year after the xth time of counting”), but later also partly annually (after an “xth Year of Counting ”was followed by the“ yth year of counting ”). However, this interpretation is not supported by other, higher dates. There is also a rock inscription from the “year after the 31st time of the count” and an indication that cannot be read with certainty, which probably refers to the “year of the 33rd time of the count”. So far it is unclear whether the counting under Pepi II. Took place regularly every two years or irregularly, since a total of six years of counting (2, 11, 12, 14, 31 and possibly 33) but only three or four statements of "years after the count ”(11, 22 and 31 and possibly 1) have been handed down. He therefore has a minimum term of 34 years and a maximum of 62 to 66 years.

The latter is considered plausible by the majority of researchers today, also because two sed festivals are documented for Pepi's reign . Jürgen von Beckerath , for example, assumes 60 years and Thomas Schneider 65 years.

State administration

At the beginning of Pepi's reign his mother Anchenespepi II acted as regent, but his uncle Djau also played an important role. This held the provincial vizier in Abydos . He was later followed by Idi and Pepinacht. Ankh-Pepi-Heriib and Ankh-Pepi-Henikem are known as viziers in Meir . Residency viziers in Memphis were Ihichenet and Chenu, Ima-Pepi and Schenai, Chabau-Chnum / Biu and Nihebsed-Neferkare and Teti.

The important office of the vizier was restructured under Pepi II. The title of “head of all the king's works” was now directly linked to the residence vizier. He was thus directly responsible for the royal building projects and for the recruitment of workers. In return, however, the offices of barn and treasury head , which were previously very closely associated with the viziers, were now increasingly occupied by non-viziers. In the provincial administration, for Pepi's reign it can be established that at least occasionally the office of barn manager was also carried out by viziers. However, this was almost never the case with the office of treasurer. The distribution of the titles suggests that Pepi originally intended to equate the provincial administration with the residence administration or even to make it independent of it. However, this was only partially implemented for the barn department and practically not at all for the treasury department. Instead, control over both departments remained de facto with the residence administration due to the occupation with lower-ranking officials in the province.

External relations and expeditions

Numerous expeditions from Pepi's reign are documented by inscriptions, including one to the copper and turquoise mines of Wadi Maghara on the Sinai Peninsula in the 2nd year of the count and two expeditions to the alabaster quarries of Hatnub in Central Egypt , which took place in the 14th century The year of the census and the year after the 31st time the census took place. Trade contacts with the city of Byblos in today's Lebanon are also evidenced by numerous finds (especially alabaster vessels) with Pepi's name, which were found in the temple there.

As with his predecessor Merenre, trade with Nubia also played a central role. Relations with the south, however, were dominated by increasing hostilities under Pepi's rule. In Pepi's second year in power, the Elephantine official Harchuf made a trip to the country of Jam . He had already traveled to Nubia three times under Merenre and described these journeys in detail in his tomb on the Qubbet el-Hawa . From these reports it emerges that a changed political situation made it visibly more difficult for him to return home on his third expedition and that he only got back safely to Egypt thanks to a strong contingent of troops from the Prince of Jam. There is no report of his fourth and final trip. Instead, Harchuf had a copy of a letter from young Pepi II affixed to his grave, in which he expressed his great joy that Harchuf had brought him a " dancing dwarf " (probably a pygmy ) from Jam and admonished him to take good care of him .

The journeys mentioned in the tomb of Chui on Qubbet el-Hawa seem to have been largely peaceful . There a servant named Chnumhotep reports that he, together with his master Chui and another high official named Tjetji, made a total of eleven trips to Nubia and to Punt in what is now Eritrea or Somalia .

In contrast, Sabni reports hostile clashes in his grave on Qubbet el-Hawa. His father Mechu I. had led an expedition to Nubia and died there. Apparently he had been murdered because his body initially remained in Nubia and Sabni had to march to Nubia with a larger contingent of soldiers to bring him home. Sabni himself apparently died immediately after his return from a Nubia expedition in Elephantine. His son Mechu II was staying in Nubia himself at the time and after his return received the support of the royal residence to furnish his father's grave.

Another inscription on the Qubbet el-Hawa comes from Pepinacht, called Heqaib . He reports on two military operations in Nubia . The king had sent him to "hack" the two countries of Wawat and Irtjet . Pepinacht reports that on his first campaign he killed several princely children and military leaders and brought large numbers of prisoners of war to Egypt. On his second campaign he finally captured the two princes of Wawat and Irtjet as well as their children and two high commanders and brought them to Egypt along with numerous cattle and goats. A third military expedition took Pepinacht to the eastern desert. There the commander Aaenanch and his escort group of Bedouins (called "sand dwellers" by the Egyptians) were murdered while they were building a ship that was to make a trip to Punt. Pepinacht led a punitive expedition against the Bedouins and brought Aaemanch's body back to the residence.

After the death of Pepis II, the expeditions to the areas outside Egypt came to a temporary end. The Wadi Maghara was not revisited until around 200 years later in the 12th Dynasty . Trade contacts with Byblos are also only documented again at this time. Expeditions to Punt took place again under Mentuhotep III. ( 11th Dynasty ), while Nubia did not come under Egyptian control again until the 12th Dynasty.

End of government and collapse of the Old Kingdom

After Pepi, his son Nemtiemsaef II ascended the throne first. But he only ruled for about a year. He was followed by a large number of other rulers who also ruled only briefly. They increasingly lost control of the state administration, until Egypt finally fell into two spheres of power: Herakleopolis in the north and Thebes in the south.

The reasons for this decline in the Egyptian central state can certainly be found in Pepi's tenure. However, they have not yet been conclusively clarified and were probably of a complex nature. Whereas in older works the view was predominantly held that the main reason lay in the increasing striving for autonomy and an increasing power of the Gau princes (such as James Henry Breasted but also Wolfgang Helck ), systematic studies of civil servant titles and their bearers have, however, shown that there was a decentralization of the administration and a general growth of the civil service. Central key departments such as that of the head of the barn and treasure house, but also that of the head of all the king's work, however, remained very closely linked to the residence administration and thus directly linked to the king. According to Petra Andrássy, there was no evidence of a strong increase in the power of the princes, neither in the economic nor in the military area. According to her, the general growth of the civil service seems to have become a crisis factor, as their supply became more and more a problem. For example, the ever-decreasing size of private graves indicates a scarcity of resources. The increased exemption of the temples from taxes also seems to have weakened the scope of action of the residence administration. Climatic factors, above all falling amounts of precipitation combined with low Nile floods, apparently exacerbated Egypt's economic problems.

According to a more recent proposal by Karl Jansen-Winkeln , the main factor behind the downfall of the Old Kingdom was neither an administrative crisis nor unfavorable climate change, but primarily an invasion of the Nile Delta by tribes from the Middle East. Jansen-Winkeln bases his argumentation mainly on written sources such as the teaching for Merikare . But more recent excavations in the delta also seem to support his hypothesis. The city of Mendes was apparently destroyed at the end of the 6th Dynasty and its inhabitants murdered.

Construction activity

The Pepi II pyramid in Saqqara South

For his pyramid complex with the name Men-Anch-Neferkare (“The life of Neferkare lasts”), Pepi II chose a location in Saqqara- South, immediately northwest of the Mastabat al-Firʿaun of Sheepseskaf from the 4th dynasty . The complex was uncovered by Gustave Jéquier between 1926 and 1932 . In terms of its dimensions and structure, the pyramid follows a standard program that has been established since Djedkare and is therefore largely identical to its predecessor buildings. It has a side length of 78.75 m and an original height of 52.5 m. It thus represents the last great building of the Old Kingdom. The core of the building consists of limestone pieces that are connected with clay mortar; the cladding blocks are made of tura limestone . As part of a subsequent expansion, a 7 m wide wall belt was placed around the completed pyramid around the entire building. The north chapel was demolished and the already built surrounding wall had to be moved several meters.

The entrance to the underground chamber system is on the north side. From here a corridor leads diagonally downwards. It first opens into a chamber and then continues horizontally. The corridor has a blocking device made of three massive granite falling stones. Its walls are decorated with pyramid texts. The antechamber is located directly below the center of the pyramid. The Serdab branch off to the east and the burial chamber to the west . The Serdab consists of only one room and has no niches. The antechamber and the burial chamber have a gable roof decorated with stars. The walls of the chambers have pyramid texts, but the west wall of the burial chamber is designed as a palace facade . The granite sarcophagus and the lid of a canopic cupboard were found in the burial chamber . The mummy of Pepis II was not preserved.

In front of the valley temple was a wide, northwest-southeast oriented terrace, which ran along a canal. At both ends, ramps provided access to the terrace from the water. In the middle of the terrace was the entrance to the valley temple. The temple consists of a pillar hall, a vestibule behind it and several storage rooms. Several scenes have survived from the wall decoration of the temple. The avenue running in a south-westerly direction connects the valley temple with the mortuary temple .

The mortuary temple initially has three chapels in which the three religious centers of Heliopolis , Sais and Buto are represented. This is followed by the entrance hall and a courtyard surrounded by pillars. To the north and south of it are magazines. Behind the courtyard is a cross corridor that separates the public from the intimate area of the temple. Numerous remnants of the relief decoration have been preserved in the corridor, including depictions of the Sed festival, the Min festival and the execution of a Libyan prince. The latter, however, is a copy of a representation from the mortuary temple of the Sahure pyramid and therefore does not refer to a real event. The inner part of the temple consists of a cult chapel with five niches, an antichambre carrée and an offering hall. To the north and south of these rooms are further storage rooms. The anitchambre carrée has images of the court who pays homage to the king; in the sacrificial hall the king is depicted in embrace with gods. A small cult pyramid was erected southeast of the royal pyramid .

The pyramid complex

To the south and north-west of his own pyramid complex, Pepi had three pyramid complexes built for his wives Wedjebten, Neith and Iput II outside the enclosure wall. The pyramids of Neith and Iput II are located on the northwest corner of the royal tomb complex. The Neith pyramid is the oldest of the three systems. The chamber system consists of a descending corridor with a blocking stone, a burial chamber and a serdab. The ceiling of the burial chamber is decorated with stars, the walls with pyramid texts or in the west with a palace facade. Numerous broken stone vessels were preserved from the burial equipment. The mortuary temple is south of the pyramid. It consists of a vestibule, a courtyard surrounded by pillars, storage rooms, a sacrificial hall and a room with three niches in which the statues of the queen originally stood. A small cult pyramid is located south-east of the queen pyramid. Between the two structures, 16 wooden ship models were found in a pit. The entire facility is surrounded by its own wall.

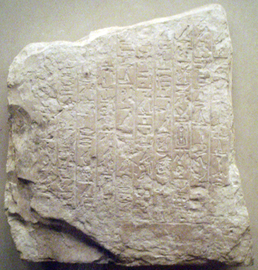

The pyramid of Iput II is located southwest of the Neith pyramid and is slightly smaller than this. The chamber system and the mortuary temple have the same structure as the Neith pyramid, there is also a small cult pyramid. After Pepi's death, Anchenespepi IV was buried in one of the storage rooms, for whom a queen pyramid was no longer erected. Its sarcophagus lid, which was a converted annals stone, is of particular importance .

The Wedjebten Pyramid is located south of the King's Pyramid. The heavily destroyed building has two enclosing walls, its own mortuary temple and a small cult pyramid. Fragments of pyramid texts that originally adorned the burial chamber and perhaps also the corridors were found in the underground chamber system.

Above all to the north and east, and to a lesser extent south and west of the Pepi II pyramid, numerous private graves were also built. These cemeteries were used until the beginning of the First Intermediate Period and to a lesser extent in the Middle Kingdom .

Construction outside of Sakkaras

Little is known about Pepi's building activity outside of Sakkaras. A procession of 117 domains (agricultural goods) and Ka houses, which were responsible for the supply of the royal sacrificial cult, is depicted on the walls of the pathway to his pyramid complex. In addition, the transport of two obelisks from Lower Nubia to Heliopolis is recorded in Sabni's autobiography . Pepi's building activity from Koptos is documented by two relief blocks (today in the Petrie Museum , London , inv.no. UC 14281 and in the Manchester Museum ) and by several decrees.

Statues

Only two statues that can be safely assigned to Pepi II have been preserved. The first is of unknown origin and is now in the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York (inv.no.39.119). It is made of alabaster and has a height of 38.9 cm, a width of 17.8 cm and a depth of 25.2 cm. This piece, which is unique for the Egyptian royal sculpture, shows the queen mother Anchenespepi II sitting on a throne. She is identified by a name inscription at her feet. According to her rank, Anchenespepi wears a vulture hood over her wig . The head of the vulture was originally made separately from stone or metal and pegged into the forehead of the statue, but is now lost. Her son Pepi II sits on Anchenespepi's lap. Although this is obviously a representation of the child king, he is shown in the typical posture and in full regalia of an adult ruler. He wears an apron and a Nemes headscarf . He has clenched his right hand on his thigh and holds a folded cloth in it. His mother protects him with her hands on his back and on his knees. The block under the king's feet gives Pepi's name with the addition "loved by Khnum ", which could be an indication that the statue originally came from Elephantine , the main place of worship of the Khnum.

The second statue was found by Gustave Jéquier in the mortuary temple of the Pepi II pyramid and is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (inv.no. JE 50616). It is also made of alabaster and shows the king as a child. Pepi is shown naked and crouching. He has short hair and a uraeus snake on his forehead. His right hand, which is no longer preserved today, was originally held to his mouth.

In the case of a third piece, the assignment to Pepi II is not certain, but based on stylistic comparisons it is quite probable. It is the head of a statue made of alabaster, which also shows a child king and is very similar to the piece from Cairo. The piece is of unknown origin and is now in the Petrie Museum in London .

Even the head of a fourth statue can only be classified stylistically in the reign of Pepi II. It was acquired in the art trade in 1966 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City . The head is made of black stone and shows a king with a Nemes headscarf.

In addition, it is known from a decree from Koptos that Pepi II had a king statue made from copper and placed in the Min Temple. The statue itself has not survived, however.

Other finds

From Byblos come two small, incompletely preserved anointing oil vessels made of alabaster in the form of female monkeys holding a young to the breast. Very similar, completely preserved pieces of unknown origin are also known from the reigns of Pepi I and Merenre.

A vase-shaped vessel with a lid made of alabaster, which is now in the Louvre in Paris (Inv.No. N 648a, b) and was originally made to commemorate a Sed festival by Pepis II, is of unknown origin. It has a height of 15 cm and a diameter of 19.9 cm. Similar, incompletely preserved vessels from Pepi's reign were also found in Byblos, where this type of vessel has been regularly traded since Neferirkare ( 5th dynasty ).

Also of unknown origin is a headrest with Pepi's signature, which is now in the Louvre (inv. No. N 646). It is made of ivory (probably from the elephant) and has a height of 21.8 cm, a width of 19.1 cm and a depth of 7.8 cm. It was probably a present from Pepi for the burial equipment of an official.

Pepi II in memory of ancient Egypt

One of the decrees from the Temple of Min in Koptos shows that a sacrificial cult was practiced for the copper statue of Pepi placed there during the reign of Wadjkare in the 8th dynasty .

Pepi II and his pyramid are mentioned in various private inscriptions of the Middle Kingdom. The cult at the pyramid was still in operation in the Middle Kingdom.

In later times Pepi II was mentioned in at least two works of ancient Egyptian literature . The first is The Tale of Hai from the Middle Kingdom . The only surviving text carrier is so badly damaged that only individual fragments of the story can be reconstructed. The setting is probably Memphis , as the pyramid Pepis II is explicitly mentioned. The content of the story appears to center around the murder and funeral of a man named Hai.

The incompletely preserved history of Neferkare and Sasenet originated in the Middle or New Kingdom . It deals with a homosexual relationship between Pepi II (Neferkare) and his General Sasenet. The relatively well-preserved middle section of the story describes how a man wants to bring a lawsuit to the king. But instead of listening to him, Pepi drowns him out with music and singing until he leaves, disappointed. The man then instructs a friend to shadow the king. The friend has already heard rumors that he has now found confirmed: The king secretly goes to his general's house every night and stays there for four hours. Since the beginning of the story is only fragmentary and the end has not been preserved, an interpretation of the story is difficult.

A relief block in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin comes from the New Kingdom and is said to come from a grave in Saqqara . It depicts five enthroned kings of the Old Kingdom: The name of the first is no longer preserved, but it can probably be reconstructed to Snefru on the basis of old photographs ; it is followed by Radjedef , Mykerinos , Menkauhor and Pepi II. (Neferkare). The image section preserved on this block can be reconstructed as a worship scene in which the grave owner stands in front of the kings.

The most recent mention of Pepi is in the Brooklyn Medical Papyrus 47,218.48 / 47,218.85, dating from around 300 BC. BC originated. There, in addition to the behavior of the snake towards humans, a remedy for snake bites is described in section 42c, the discovery of which is dated to the reign of Pepi.

literature

General

- Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Volume I: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, Oakville 2008, ISBN 978-0-9774094-4-0 , pp. 295-297.

- Peter A. Clayton: The Pharaohs. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1995, ISBN 3-8289-0661-3 , pp. 65-67.

- Martin von Falck, Susanne Martinssen-von Falck: The great pharaohs. From the early days to the Middle Kingdom. Marix, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3737409766 , pp. 168-176.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 193-195.

- Joyce Tyldesley : The Pharaohs. Egypt's most important ruler in 30 dynasties. National Geographic Germany, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-86690-114-8 , pp. 57-59.

About the name

- Kurt Sethe : Documents of the Old Kingdom. Volume 1 (= documents of ancient Egypt. Volume 1,1). Hinrichs, Leipzig 1903, p. 114.

- Kurt Sethe: The ancient Egyptian pyramid texts. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1908, Spruch No. 7, 112, N.

- WMFlinders Petrie : Koptos. Quaritch, London 1896, plate V 7.

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Handbook of the Egyptian king names. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-422-00832-2 , pp. 57, 185.

To the pyramid

- Zahi Hawass : The Treasures of the Pyramids. Weltbildverlag, Augsburg 2004, ISBN 3-8289-0809-8 , pp. 272-275.

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids. Orbis, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-572-01039-X , pp. 161-163.

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , pp. 196-203.

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 399-405.

For further literature on the pyramid see under Pepi-II.-Pyramid

Questions of detail

- Michel Baud: The Relative Chronology of Dynasties 6 and 8. In: Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton (Eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology (= Handbook of Oriental studies. Section One. The Near and Middle East. Volume 83 ). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2006, ISBN 90-04-11385-1 , pp. 144–158 (online)

- Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3 , pp. 70-78 ( PDF file; 67.9 MB ); retrieved from the Internet Archive .

- Naguib Kanawati: Governmental Reforms in Old Kingdom Egypt (= Modern Egyptology series. ). Aris & Phillips, Warminster GB 1980, ISBN 0-85668-168-7 , pp. 62-103.

- Alessandro Roccati: La littérature historique sous l'Ancien Empire Egyptien (= Littératures anciennes du Proche-Orient. Volume 11). Editions du Cerf, Paris 1982, ISBN 2-204-01895-3 , pp. 198-220.

- Nigel Strudwick: The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: the highest titles and their holders (= Studies in Egyptology. ). Kegan Paul International, London / Boston 1985, ISBN 0-7103-0107-3 .

- Laure Pantalacci: Un décret de Pépi II en faveur des gouverneurs de l'oasis de Dakhla [avec 1 planche]. In: Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. (BIFAO) Vol. 85, Cairo 1985, pp. 245-254.

- Renate Müller-Wollermann: Crisis factors in the Egyptian state of the ending Old Kingdom. Dissertation printing, Darmstadt 1986; at the same time dissertation. Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen.

- Hans Goedicke: The Death of Pepi II - Neferkareˁ. In: Studies on ancient Egyptian culture. (SAK) Volume 15, Hamburg 1988, pp. 111-121.

- Hans Goedicke: The Pepi II Decree from Dakhleh [avec 1 planche]. In: Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. Volume 89, Cairo 1989, pp. 203-212.

- E. Schott: The gold house under King Pepi II. In: Göttinger Miszellen . (GM) No. 9, Göttingen 1974, pp. 33-38.

- Benjamin Geiger: Egypt in the government of Pepis II. Investigation of the disintegration of the administrative system of the Old Kingdom. Dissertation. University of Zurich, Zurich 1990.

- James F. Romano: A Sed-Festival Statuette of Pepy II in the Brooklyn Museum. In: Göttinger Miscellen. No. 120, Göttingen 1991, pp. 73-84.

- James F. Romano: Mastabas in Balat. In: Michel Valloggia, Nessim Henry Henein, Jean Vercoutter: Balat. Volume I: Le Mastaba de Medou-Nefer (= Fouilles de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale du Caire. Volume 31). Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale du Caire (IFAO), Le Caire 1986; Volume II: Le Mastaba d'Ima-Pepi (= Fouilles de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale du Caire. Volume 33). IFAO, Le Caire 1992.

- Michel Vallogia: Un groupe statuaire découvert dans le mastaba de Pepi-Jma à Balat (avec 4 planches). In: Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. Volume 89, Cairo 1989, pp. 271-282 with panels 33-35.

- Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronology of the pharaonic Egypt. von Zabern, Mainz 1994, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 , pp. 27, 40, 73, 148-152, 188.

Web links

- The Ancient Egypt Site (English)

- Pepi II. On Digital Egypt (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Year numbers according to Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs . Düsseldorf 2002.

- ^ Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London 2004, pp. 70-78.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: History of ancient Egypt (= Handbook of Oriental Studies. Dept. 1: The Near and Middle East. Volume 1). Brill, Leiden / Cologne 1981, p. 75, ( online version ).

- ^ Anthony Spalinger: Dated Texts from the Old Kingdom. In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture. Volume 21, 1994, pp. 307-308.

- ↑ Michel Baud: The Relative Chronology of Dynasties 6 and 8. Leiden / Boston 2006, pp. 152-153, 156.

- ↑ Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1994, p. 150.

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 315.

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, pp. 193-194.

- ↑ Petra Andrássy: Investigations on the Egyptian state of the Old Kingdom and its institutions (= Internet contributions on Egyptology and Sudan archeology. Volume XI). Berlin / London 2008 ( PDF; 1.51 MB ), pp. 41–42.

- ↑ James Henry Breasted : Ancient records of Egypt. Historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I: The first to seventeenth dynasties. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1906, §§ 339–343 ( PDF; 12.0 MB ).

- ^ Bertha Porter , Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. VII. Nubia, the Deserts, and Outside Egypt. Griffith Institute, Oxford 1952, Reprint 1975, ISBN 0-900416-23-8 , pp. 388-391 ( PDF; 21.6 MB ).

- ↑ James Henry Breasted: Ancient records of Egypt. Historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I: The first to seventeenth dynasties. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1906, §§ 335–336, 350–354 ( PDF; 12.0 MB ).

- ↑ James Henry Breasted: Ancient records of Egypt. Historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I: The first to seventeenth dynasties. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1906, §§ 355-360 ( PDF; 12.0 MB ).

- ↑ James Henry Breasted: Ancient records of Egypt. Historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I: The first to seventeenth dynasties. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1906, §§ 362–374 ( PDF; 12.0 MB ).

- ↑ Elmar Edel : The excavations on the Qubbet el Hawa 1975. In: Walter F. Reineke (Ed.): First International Congress of Egyptologists, Cairo 2. – 10. October 1976 (= writings on the history and culture of the ancient Orient. Volume 14). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1979, pp. 194–196.

- ↑ James Henry Breasted: Ancient records of Egypt. Historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I: The first to seventeenth dynasties. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1906, §§ 355-360 ( PDF; 12.0 MB ).

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. VII. Nubia, the Deserts, and Outside Egypt. Griffith Institute, Oxford 1952, Reprint 1975, ISBN 0-900416-23-8 , p. 341 ( PDF; 21.6 MB ).

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. VII. Nubia, the Deserts, and Outside Egypt. Griffith Institute, Oxford 1952, Reprint 1975, ISBN 0-900416-23-8 , pp. 387-392 ( PDF; 21.6 MB ).

- ↑ Kenneth Anderson Kitchen : Punt. In: Wolfgang Helck , Eberhard Otto (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie. Volume IV. Megiddo pyramids. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1982, Sp. 1199.

- ↑ Steffen Wenig : Nubia. In: Wolfgang Helck, Eberhard Otto (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie. Volume IV. Megiddo pyramids. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1982, Sp. 529.

- ↑ James Henry Breasted: History of Egypt. Parkland, Cologne 2001 (reprint of the 1957 edition), ISBN 3-89340-008-7 , p. 102.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: History of ancient Egypt (= Handbook of Oriental Studies. Dept. 1: The Near and Middle East. Volume 1). Brill, Leiden / Cologne, 1st edition. 1968, pp. 76-78, ( online version, 1981 edition ).

- ↑ Petra Andrássy: Investigations on the Egyptian state of the Old Kingdom and its institutions (= Internet contributions on Egyptology and Sudan archeology. Volume XI). Berlin / London 2008 ( PDF; 1.51 MB ), p. 137.

- ↑ Petra Andrássy: Investigations on the Egyptian state of the Old Kingdom and its institutions (= Internet contributions on Egyptology and Sudan archeology. Volume XI). Berlin / London 2008 ( PDF; 1.51 MB ), pp. 137–140.

- ^ Eva Martin-Pardey: Investigations into the Egyptian provincial administration up to the end of the Old Kingdom. Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1976, p. 150.

- ^ Jaromir Malek: The Old Kingdom (c.2686-2160 BC). In: Ian Shaw (Ed.): The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, ISBN 0-19-280458-8 , p. 107.

- ↑ Karl Jansen-Winkeln: The fall of the Old Empire. In: Orientalia. Nova Series. (Or) Volume 79, Rome 2010, pp. 302-303.

- ^ Donald Redford: City of the Ram-Man: The story of ancient Mendes. Princeton University Press, Princeton 2010, ISBN 978-0-691-14226-5 , pp. 46-50.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 399-400.

- ↑ Mark Lehner: Secret of the pyramids. ECON, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-572-01039-X , p. 161.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 400-401.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 404-405.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 401-403.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 405-407.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 407-408.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 408-409.

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. III 2 . Memphis. Part 2. Ṣaqqara to Dahshûr. 2nd Edition. University Press, Oxford 1981, ISBN 0-900416-23-8 , pp. 676-687 ( PDF; 33.5 MB ).

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 194.

- ↑ Dorothea Arnold: Relief Fragment from Coptos. In: Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, ISBN 0-87099-906-0 , pp. 444-445.

- ↑ Catharine H. Roehrig: Pair Statue of Queen Ankh-nes-meryre II and Her Son Pepi II Seated. In: Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, ISBN 0-87099-906-0 , pp. 437-439.

- ↑ Audran Labrousse: The pyramids from the time of the 6th Dynasty. In: Zahi A. Hawass (ed.): The treasures of the pyramids. Weltbild, Augsburg 2004, ISBN 3-8289-0809-8 , p. 272.

- ^ UCL Petrie Collection Online Catalog .

- ↑ metmuseum.org: Royal head from a small statue

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Schenkel: Memphis · Herakleopolis · Thebes. The epigraphic evidence of the 7th – 11th centuries Dynasty of Egypt (= Egyptological treatises. Volume 12). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1965, pp. 12-14.

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. VII. Nubia, the Deserts, and Outside Egypt. Griffith Institute, Oxford 1952, Reprint 1975, ISBN 0-900416-23-8 , p. 391 ( PDF; 21.6 MB ).

- ^ Dorothea Arnold: Three Vases in the Shape of Mother Monkeys and their Young. In: Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, ISBN 0-87099-906-0 , pp. 446-447.

- ↑ Christiane Ziegler: Jubilee Jar Inscribed with the Name of Pepi II. In: Metropolitan Museum of Art (ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, ISBN 0-87099-906-0 , p. 449.

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. VII. Nubia, the Deserts, and Outside Egypt. Griffith Institute, Oxford 1952, Reprint 1975, ISBN 0-900416-23-8 , pp. 390-391 ( PDF; 21.6 MB ).

- ↑ Christiane Ziegler: Headrest Inscribed with the name of Pepi II. In: (ed.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, ISBN 0-87099-906-0 , pp. 452-453.

- ↑ Farouk Gomaa: The colonization of Egypt during the Middle Kingdom, II Lower Egypt and the adjacent areas.. Wiesbaden 1987, ISBN 3-88226-280-X , pp. 28-29.

- ^ Günter Burkard , Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history. Volume 1: Günter Burkard: Old and Middle Kingdom (= introductions and source texts on Egyptology. Volume 1). LIT, Berlin et al. 2003, ISBN 3-8258-6132-5 , p. 201.

- ^ Günter Burkard , Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history. Volume 1: Günter Burkard: Old and Middle Kingdom (= introductions and source texts on Egyptology. Volume 1). LIT, Berlin et al. 2003, ISBN 3-8258-6132-5 , pp. 187-191.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Part I. Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties (= Munich Egyptological Studies. (MÄS) Volume 17). Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1969, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Kamal Sabri Kolta: Papyri, medical. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 1096-1099; here: p. 1098.

- ↑ John F. Nunn: Ancient Egyptian Medicine. The British Museum Press, London 1996, ISBN 0-7141-1906-7 , p. 183.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Merenre |

King of Egypt 6th Dynasty |

Nemtiemsaef II. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pepi II. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Nefer-ka-re; Neteri-Chau; Phiops II |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | 5th King of Egypt in the 6th Dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | before 2245 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 2180 BC Chr. |