Merenre

| Name of Merenre | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horus name |

Ankh -chau ˁnḫ-ḫˁw With living appearances |

||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Ankh -chau-nebti ˁnḫ-ḫˁw-nbtj With living appearances of the two mistresses |

||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Nbwj-nbw Gold of the two falcons

Bjkwj-nbw The one with the two golden hawks ? |

||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Mrj-n-Rˁ Who is loved by Re |

||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

Nmtj m s3 = f Nemti is his protection |

||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Abydos (Seti I) (No.37) |

Mrj-n-Rˁ |

||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Saqqara (No.35) |

Mrj-n-Rˁ |

||||||||||||||

|

Greek for Manetho |

Menthesuphis Menthesuphis |

||||||||||||||

Merenre ( Meri-en-Re , also Merenre I. , Nemtiemsaef I. or Antiemsaef I. ) was the fourth king ( pharaoh ) of the ancient Egyptian 6th dynasty in the Old Kingdom . He ruled approximately within the period from 2250 to 2245 BC. He succeeded his father Pepi I to the throne and probably only ruled for a few years. Rock inscriptions and written testimonies from the graves of high officials are important sources for his rule. On the one hand, they indicate a continuation of the ever increasing decentralization of the state administration in the late Old Kingdom. Another focus of his reign were intensive contacts to Nubia, with the Weni quarry expeditions and the Harchuf's trade and discovery trips in particular, which are described in detail in the autobiographies of the two officials. The most important building project in Merenre is its pyramid complex in the south of Saqqara , which however remained unfinished. A relatively well-preserved mummy was found in the burial chamber of the pyramid in the 19th century, but it is unclear whether it is actually Merenre's body or a subsequent burial from the 18th dynasty .

Name and numbering

The king had the proper name Nemtiemsaef or in another reading Antiemsaef ("(The God) Nemti (or Anti) is his protection") and the throne name Merenre (" Who is loved by Re "). He is out in the literature mostly under his throne name, but occasionally under its own name or under that of Manetho traditional Hellenised name form Menthesuphis .

It is often numbered Merenre I./Nemtiemsaef I. to distinguish it from Nemtiemsaef II . However, this is only correct for the proper name, since there is no contemporary evidence that Nemtiemsaef II also carried the throne name Merenre and that the naming in the list of kings of Abydos created under Seti I is probably a copy error by a clerk.

Origin and family

Merenre was a son of Pharaoh Pepi I and his wife Anchenespepi I (also called Anchenesmerire I). Half- brothers were his successor to the throne Pepi II. , Tetianch and Hornetjerichet , a half-sister was Neith , a later wife of Pepi II. Merenre's only known wife is Anchenespepi II. (Anchenesmerire II.), The sister of his mother and widow of his father Pepi I. Das Merenre's only known child is a daughter named Anchenespepi III. , another later wife of his half-brother Pepi II.

Domination

Term of office

Although Merenre's reign cannot have been very long, there is great uncertainty about its exact duration. In the Royal Papyrus Turin from the New Kingdom , the year of its entry is very poorly preserved. Only four lines, which can be read as “4”, are clearly visible. There are several characters in front of them that have been read by different researchers as “10”, “40” or as a word mark for “month”. So there are three possible readings: 44 years, 14 years and x years and 4 months. While the first option is unanimously seen as unrealistic, the other two are discussed controversially. Wolfgang Helck suggested a reading as "[6] years and 4 months", which corresponds to the information about the 3rd century BC. BC living Egyptian priest Manetho , who indicates 7 years of reign for Merenre. The contemporary dates do not provide clarity here, as only four have survived. The highest date is a “year after the 5th count”. This refers to the nationwide cattle count, originally introduced as the escort of Horus , for the purpose of tax collection. This census originally took place every two years (that is, an “xth year of counting” was followed by a “year after the xth time of counting”), but later also partly annually (for an “xth year the count ”was followed by the“ yth year of the count ”). Since data from Merenre's government are available for two years of the census and the following years after the census, there is therefore a minimum documented term of government of 7 years and a maximum of 11 or 12 years. Despite these uncertainties, the majority of researchers tend to have short reigns. For example, Helck's suggestion by Thomas Schneider or Jürgen von Beckerath is accepted. The possibility of a 14-year government is represented by William Stevenson Smith , who has to make some problematic additional assumptions: Since Pepi II ascended the throne as a child, Merenre would have had to rule with his father Pepi I for several years. As a result, Anchenespepi I would initially leave as Merenre's mother. On the other hand, such a co-rule, which was quite common in the 12th Dynasty , is completely unproven for the Old Kingdom. Smith only cites a gold pendant on which the names of Pepi I and Merenre appear together.

State administration

Only a few sources are available on the exact extent of the reforms of the state administration initiated under Merenre. It can be seen, however, that the long-lasting trend towards decentralization in Egypt continued. This is made clear by the fact that the princes and rulers of Upper Egypt no longer resided in Memphis , but in the provinces and the latter were buried there for the first time. In addition, new institutions were set up in the royal residence that were specifically responsible for the administration of Upper Egypt.

Relations with Nubia

During Merenre's reign, Nubia became the focus of Egypt's foreign policy interests. Two rock inscriptions near Aswan testify to this , showing the king accepting the submission of the sub-Nubian princes. The first is on the old road between Aswan and Philae . It is not dated, but shows the king standing on a union symbol, which could indicate his first year in reign. The second inscription is located opposite the island of el-Hesseh and dates back to Merenre's 5th year of the count. Another royal inscription can be found in Tômas in Lower Nubia.

Other important evidence are the autobiographical inscriptions of two high officials. The first is Weni buried in Abydos . He already served under Pepi I and at that time waged war against Bedouins on the Sinai Peninsula five times by means of soldiers recruited in Nubia . Under Merenre he was appointed "Chief of Upper Egypt" and at an advanced age he carried out two expeditions to Nubian quarries. The first took him to Ibhat , from where he brought the sarcophagus and pyramidion for the king's pyramid and to the granite quarries of Elephantine , where he had a false door and a sacrificial tablet made. The second expedition took him to an unspecified location in Nubia. From there he again brought building materials for the royal pyramid. In order to avoid the rapids on the first cataract of the Nile , Weni had five canals dug and local Nubians built transport ships.

Another important official was Harchuf , who after Weni also rose to the position of "Chief of Upper Egypt". As can be seen from the autobiography in his grave on the Qubbet el-Hawa near Aswan, he undertook a total of three expeditions under Merenre that took him deep into Nubia and the Libyan desert to explore the countries there and to do business. Harchuf made the first trip together with his father Iri. It lasted seven months and led to the Land Jam, which had not yet been safely located . Further details have not been handed down. The second trip, led by Harchuf alone, lasted eight months and took him through several Nubian countries. The third trip is the most detailed and took place under difficult conditions. Harchuf met the ruler of Jam while he was on a campaign against Libyans. After a barter trade, the ruler of Jam provided him with soldiers that Harchuf needed in order to be able to safely pass the countries of Irtjet and Satju on the way back , whose rulers had in the meantime also conquered the neighboring country of Wawat .

Other events

In addition to the Nubia expeditions, only a few events from Merenre's reign are known. Weni mentions another expedition in his autobiography that took him to the alabaster quarries of Hatnub in Middle Egypt , where he had a sacrificial tablet made. Another quarry expedition commissioned by Merenre is documented in Wadi Hammamat . In Giza , fragments of a decree that favored the local priesthood were found in the mortuary temple of the Mykerinos pyramid.

Construction activity

The Merenre pyramid in Saqqara

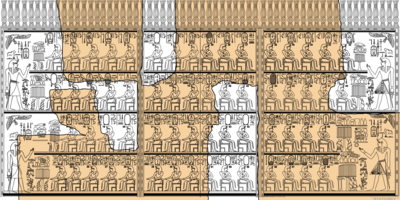

The only major construction project known with certainty from Merenre's reign is his pyramid complex in Saqqara- South. The building, which was first examined more closely in 1881, remained unfinished and is in a very poor condition due to stone robbery in later times. As the site of his grave conditioning Merenre chose a place southwest of the grave conditioning his father and west of Djedkare pyramid from the end of the 5th Dynasty . Architecturally, the pyramid follows a standard program that has been established since Djedkare and is therefore largely identical to the other pyramids of the late 5th and 6th dynasties. It has an edge length of 78.60 m and a planned height of 52.40 m. On the north side of a chapel a corridor leads downwards at an angle, which initially leads into a chamber. From there, a horizontal corridor blocked by falling stones leads to the antechamber, which is located under the center of the pyramid. From here a storage room branches off to the east and the burial chamber to the west. The vestibule and burial chamber have a gable roof that is painted with stars. The walls of the corridors and chambers are also decorated, including with pyramid texts . In addition to the sarcophagus , which still contained a mummy (see below), a canopic box and modest remains of the burial equipment were found in the burial chamber . The pyramid complex also remained unfinished. As early as the 1830s, John Shae Perring identified an enclosure wall made of adobe bricks and an access path that makes a kink to bypass the Djedkare pyramid and connects a presumed port facility in Wadi Tafla with the mortuary temple. Of the latter, only the limestone pavement and some remains of the wall are preserved. Since some reliefs are only available as preliminary drawings, work on the temple seems to have been prematurely stopped after Merenre's early death.

Other possible construction projects

There are also indications that Merenre had work done on the Osiris temple in Kom el-Sultan near Abydos . Only fragments of several private steles that were found in the foundations of the temple, which was completely renovated in the 12th dynasty, bear witness to this. The nature and extent of the work during Merenre's reign cannot be determined from this. Merenre is also attested on Elefantine, but only by a naos .

Possible mummy of Merenre

In January 1881 the brothers Emil and Heinrich Brugsch found in the sarcophagus chamber of the Merenre pyramid the 1.66 m tall mummy of a man who apparently had died young and who was still wearing the lock . However, it was not in the sarcophagus, but next to it. The condition of the mummy was poor as it had already been damaged by grave robbers who had partially torn off the mummy bandages. Emil and Heinrich Brugsch decided at short notice to transport the mummy to Cairo to show it to the dying Auguste Mariette. However, the mummy suffered further serious damage during the transport. A rail damage prevented the mummy from being brought to Cairo by train. So the Brugschs carried them the rest of the way on foot. After the wooden sarcophagus became too heavy, they took out the mummy, breaking it in two. The mummy finally ended up in the Egyptian Museum , at that time still in Bulaq , later in its current location in Cairo . Since 2006 it has been exhibited in the Imhotep Museum in Sakkara . Skeletal remains of the collarbone, cervical vertebrae and a rib were donated by Emil Brugsch to the Egyptian Museum in Berlin (Inv.-No. 8059). However, they were lost during the relocation in World War II without an investigation ever taking place.

The parts of the mummy remaining in Egypt have not yet been examined in detail. The identity of the deceased is therefore not clearly established. While Emil and Heinrich Brugsch and Gaston Maspero still assumed that it was the remains of King Merenre, Grafton Elliot Smith expressed doubts about this as early as the beginning of the 20th century . Due to the bandaging technique, he assumed a reburial from the 18th dynasty. In current research, the find is valued differently. While Renate Germer agrees with Smith's judgment, she was still viewed by Dennis Forbes in 1997 as Merenre's mummy. Other researchers such as Mark Lehner and Rainer Stadelmann consider only a detailed examination of the mummy suitable to clarify the question of identity.

Statues

The only known round sculptural images that can be safely assigned to Merenre are two small sphinxes of unknown origin. The first is now in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh (Inv.-No. 1984.405). The piece is made of slate and measures only 5.7 cm × 1.8 cm × 3.2 cm. The king wears a ceremonial beard and a Nemes headscarf with a uraeus snake on his forehead. Instead of lion's paws, the front legs run out into human hands in which Merenre holds two spherical pots in front of him. The name Merenres is noted on the underside of the base of the Sphinx.

The second sphinx is in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow (inv.no. I.1.a.4951). According to contradicting statements, it consists either of red stone or of slate.

However, the assignment of a statue that was discovered by James Edward Quibell in Hierakonpolis at the end of the 19th century is doubtful . The standing figure is made of chased copper and is 65 cm high. It was located inside a larger copper statue, which is assigned to Pepi I by an inscription. Since the smaller statue has no inscription, there are different views of who it represents. One hypothesis assumes that it represents Merenre, who was appointed heir to the throne at the celebrations of the Sedfest Pepis I. According to another hypothesis, it is a tapered representation of Pepi I.

Other finds

A small make-up vessel that is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (inv.no. 30.8.134) is of unknown origin . It is made of alabaster and has a height of 18.5 cm. The vessel was used to store anointing oils and has the shape of a crouching female monkey that a cub is holding in front of its chest. The name Merenres is attached to the right. Two very similar pieces come from the reign of his father Pepi I.

A box kept in the Louvre in Paris (Inv.No. N 794) may come from Thebes . It consists of hippopotamus - Ivory and bears on the cover and on a narrow side the name and title of the king. The piece could be a grave gift from a dignitary buried in Thebes.

The National Archaeological Museum in Florence houses an alabaster vase (Inv.-No. 3252) bearing Merenre's name. A very similar piece comes from Elephantine and is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (inv. No. CG 18694).

Merenre in the memory of ancient Egypt

During the New Kingdom was in the 18th Dynasty under Thutmose III. In the Karnak Temple in Thebes the so-called King List of Karnak is attached, in which the name of Merenre is mentioned. In contrast to other ancient Egyptian king lists, this is not a complete listing of all rulers, but a shortlist that only names those kings for whom during the reign of Thutmose III. Sacrifices were made. So there was still a sacrificial cult for Merenre 800 years after his death.

literature

General

- Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Volume I: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, Oakville 2008, ISBN 978-0-9774094-4-0 , pp. 209-211.

- Peter A. Clayton : The Pharaohs. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1995, ISBN 3-8289-0661-3 , p. 66.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 77-79.

About the name

- Kurt Sethe : Documents of the Old Kingdom. Volume I: Documents of Egyptian antiquity; Department 1. second, greatly increased edition, Hinrichs, Leipzig 1932–33, p. 111.

- Kurth Sethe: The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1908, saying no.8.

- Friedrich Wilhelm von Bissing : Catalog Général des Antiquités Egyptienennes du Musée du Caire. Nos. 18065-18793. Stone vessels. Vienna 1904 S, 147, No. 18694.

- Jules Couyat, Pierre Montet : Les inscriptions hiéroglyphiques et hiératiques du Ouâdi Hammâmât (= Mémoires publiés par les membres de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire. Vol. 34). Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Le Caire 1912, plate 6.

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Handbook of the Egyptian king names. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-422-00832-2 , pp. 57, 185.

To the pyramid

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 398-399.

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids. ECON, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-572-01039-X , pp. 160-161.

- Zahi Hawass : The Treasures of the Pyramids. Weltbild, Augsburg 2004, ISBN 3-8289-0809-8 , p. 270.

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , p. 270.

For further literature on the pyramid see under Merenre pyramid

Questions of detail

- Michel Baud: The Relative Chronology of Dynasties 6 and 8. In: Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton (Eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology (= Handbook of Oriental studies. Section One. The Near and Middle East. Volume 83 ). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2006, ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5 , pp. 144-158 ( online ).

- Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronology of the pharaonic Egypt. von Zabern, Mainz 1994, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 , pp. 27, 40, 148-152, 188.

- Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton : The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press, London 2004, ISBN 977-424-878-3 , pp. 70-78.

- Hans Goedicke : Royal documents from the Old Kingdom. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1967, pp. 78-80.

- Werner Kaiser : City and Temple of Elephantine: Fifth excavation report. In: Communication from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK) Vol. 31, von Zabern, Mainz 1975, p. 56.

- Werner Kaiser: City and Temple of Elephantine: Sixth excavation report In: MDAIK 32, von Zabern, Mainz 1976, p. 67–112.

- Naguib Kanawati: Governmental Reforms in Old Kingdom Egypt. Aris & Phillips, Warminster (GB) 1980, pp. 44-61.

- Hans Goedicke: Harkhuf's Travels. In: Journal for Near Eastern Studies. No. 40, 1981, pp. 1-20.

- Hans Goedicke: Ya'am - more. In: Göttinger Miscellen . (GM) Vol. 101, Göttingen 1988, pp. 35-42 (Jam).

- Alessandro Roccati: La Littérature historique sous l'ancien Empire égyptien (= Littératures anciennes du Proche-Orient. Vol. 11). Éditions du Cerf, Paris 1982, ISBN 2-204-01895-3 , pp. 187-207.

- Anni Gasse: Decouvertes récentes au Ouadi Hammamat. In: Göttinger Miscellen. Vol. 101, Göttingen 1988, p. 89.

- Nigel Strudwick: The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom. KPI, London 1985, ISBN 0-7103-0107-3 .

- David O'Connor: The Location of Yam and Kush and thier historical implications. In: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. No. 23, 1986, pp. 27-50.

- David O'Connor: The Location of Irem in the New Kingdom. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology. (JEA) No. 73, 1987, pp. 99-136 (Jam).

Web links

- The Ancient Egypt Site

- Merenre I. on Digital Egypt (English)

- Phouka.com (English)

- eGlyphica - pharaohs

- Nemo.nu (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Year numbers according to T. Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Düsseldorf 2002.

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 77.

- ^ Jürgen von Beckerath: Handbook of the Egyptian king names. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1984, pp. 57, 185.

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Aidan Dodson, Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press, London 2004, pp. 70-78.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Investigations into Manetho and the Egyptian king lists (= Investigations into the history and antiquity of Egypt. Volume 18). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1956, p. 58.

- ↑ Michel Baud: The Relative Chronology of Dynasties 6 and 8. Leiden / Boston 2006, pp. 151–152, 156.

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 78.

- ↑ Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1994, p. 150.

- ^ William Stevenson Smith: The Old Kingdom in Egypt and the Beginning of the First Intermediate Period. In: IES Edwards, CJ Gadd and NGL Hammond (Eds.): The Cambridge Ancient History. Volume 1, Part 2: Early History of the Middle East. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1971, ISBN 978-0-521-07791-0 , p. 195 ( restricted online version ).

- ↑ Petra Andrassy: Investigations into the Egyptian state of the Old Kingdom and its institutions (= Internet contributions to Egyptology and Sudan archeology. Volume XI). Berlin / London 2008 ( PDF; 1.51 MB ), p. 136.

- ↑ Karl Richard Lepsius: Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia. 2nd section, volume 3, plate 116b ( online version ).

- ^ Archibald Henry Sayce: Gleanings from the land of Egypt. In: Recueil de travaux relatifs à la philologie et à l'archéologie égyptiennes et assyriennes: pour servir de bulletin à la Mission Française du Caire. Tape. 15, 1893, p. 147 ( online version ).

- ↑ Kurt Sethe (ed.): Documents of the Egyptian antiquity. Volume 1. Documents of the old empire. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1933, p. 111 ( PDF; 10.6 MB ).

- ↑ James Henry Breasted : Ancient records of Egypt. Historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I: The first to seventeenth dynasties. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1906, §§ 319-324, ( PDF; 12.0 MB ).

- ↑ James Henry Breasted: Ancient records of Egypt. Historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I, Chicago 1906, §§ 325–336, ( PDF; 12.0 MB ).

- ↑ James Henry Breasted : Ancient records of Egypt. Historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Volume I, Chicago 1906, § 323, ( PDF; 12.0 MB ).

- ↑ Rudolf Anthes: The rock inscriptions from Hatnub (= studies of the history and antiquity of Egypt. (UGAÄ) Volume 9). Hinrichs, Leipzig 1928, plate 5 VII.

- ↑ Jules Couyat, Pierre Montet: Les Inscriptions hiéroglyphiques et hiératiques du Ouadi Hammamat (= Mémoires publiés par les membres de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire. Volume 34). L'Institut Français d'Archeologie Orientale, Cairo 1912, p. 59, no. 60 ( online version ).

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 78.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 398-399; Mark Lehner: Secret of the Pyramids. ECON, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-572-01039-X , pp. 160-161.

- ^ William Matthew Flinders Petrie: Abydos. Part I. The Egypt Exploration Fund, London 1902, pp. 27, 41, pl. LIV.

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Renate Germer: Mummies. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-491-96153-X , pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Christine Mende: On the mummy find in the pyramid Merenre I. In: Sokar. Volume 17, 2008, pp. 40-43.

- ↑ Renate Germer: Remains of royal mummies from pyramids of the Old Kingdom - do they really exist? In: Sokar. Volume 7, 2003, pp. 36-41.

- ^ Dennis Forbes: The Oldest Royal Mummy in Cairo. In: KMT. Volume 8, No. 4, 1997, pp. 83-85.

- ↑ M. Lehner: Secret of the pyramids. Düsseldorf 1997, p. 160.

- ↑ R. Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world. Mainz 1991, p. 195.

- ^ Marsha Hill: Sphinx of Merenre I. In: Metropolitan Museum of Art (ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, ISBN 0-87099-906-0 , pp. 436-437.

- ↑ Jaromír Málek, Diana Magee, Elizabeth Miles: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings. Volume VIII: Objects of provenance not known. Indices to parts 1 and 2. Statues. Griffith Institute, Oxford 1999, ISBN 978-0-900416-70-5 , p. 7 ( full text as PDF file ).

- ↑ Alessandro Bongioanni, Maria Sole Croce (Ed.): Illustrated guide to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. White Star, Vercelli 2001, ISBN 88-8095-703-1 , pp. 84-85.

- ^ Dorothea Arnold: Three Vases in the Shape of Mother Monkeys and their Young. In: Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, ISBN 0-87099-906-0 , pp. 446-447.

- ^ Christiane Ziegler: Box inscribed with the Name of King Merenre I. In: Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, ISBN 0-87099-906-0 , p. 450.

- ^ Italian Touring Club: Firenze e provincia. Touring Editore, Milano 1993, ISBN 978-88-365-0533-3 , p. 352 ( limited online version ).

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm von Bissing: Catalog Général des Antiquités Egyptienennes du Musée du Caire. Nos. 18065-18793. Stone vessels. Vienna 1904, p. 147, no.18694.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung : The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Part I. Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties (= Munich Egyptological Studies. (MÄS) Vol. 17). Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin, 1969, pp. 60–63.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Pepi I. |

Pharaoh of Egypt 6th Dynasty |

Pepi II. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Merenre |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Meri-en-Re (throne name); Merenre I. (throne name); Nemtiemsaef (proper name); Antiemsaef (proper name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Egyptian king of the 6th dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | before 2250 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 2245 BC Chr. |