Wadi Hammamat

| Wadi Hammamat in hieroglyphics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New kingdom |

Ra-henu R3-hnw Wadi Hammamat |

||||

The Wadi Hammamat is one of many wadis or dry canyons in the Rocky Mountains of the Arabian desert . It forms the central part of one of the main routes between the Nile and the Red Sea .

geography

The wadi extends from the Roman way station at Bir Hammamat to the natural passage in the mountains at Bir Umm Fawakhir and is about sixty kilometers from Koptos and al-Qusair ( Myos Hormos ). It lies on one of the shortest routes between the Nile and the Red Sea and has been used accordingly over the millennia. Many ancient ruins , storage areas, hundreds of rock inscriptions and graffiti as well as ancient mining sites and quarries bear witness to this . In ancient times , mainly green breccia verde antica and bechen stone were mined here.

Inscriptions

Most of the inscriptions found are hieroglyphic and were carved on the smooth southeast rock near the main quarries for bechen . They are often dedicated to Min - the god of Coptus and the desert - or the divine triad of Coptus ( Isis , Horus and Harpocrates ). Occasionally the texts also include sacrificial scenes or images of the gods. The frequency of the depicted deities differs from epoch to epoch. In the New Kingdom , Amun-Re was increasingly worshiped, in Roman times Isis and Hathor , as well as Horus / Harpokrates and Amun / Pan .

Other inscriptions bear the names and titles of expedition leaders , often together with the names of pharaohs . Sometimes there are also details about the expeditions, such as B. the number of people taking part or the main goal of the expedition. Such inscriptions have for historical research great importance, as they are historical records of royal activities for a given year.

history

Predynastics

The oldest remains found are petroglyphs from the late Predynastic period, which were discovered immediately northeast of the bechen quarries. They show hunters , animal traps , ostriches , gazelles and other game . They are very similar to depictions on pottery from Gerzeh and are dated back to the fourth millennium BC. Chr. Dated . The diversity of the fauna and flora shown indicates that the eastern desert was a wetland in late prehistory and was inhabited by more animals and plants than it is today.

Old empire

The first hieroglyphic inscriptions come from quarry expeditions in the Old Kingdom . They name the kings Chephren , Mykerinos , Radjedef , Sahure and Unas . Pepi I from the 6th dynasty is represented particularly frequently with eight graffiti.

There are also graffiti from the First Intermediate Period , the chronology of which has not yet been clarified.

Middle realm

Most of the most significant inscriptions come from the Middle Kingdom. From the 11th dynasty are Mentuhotep II , Mentuhotep III. and Mentuhotep IV. represented with a total of thirty texts. Mentuhotep III. sent an expedition of 3,000 men to send a ship to Punt for incense and other exotic goods. The team used the return to mine bechen stone for royal statues at the same time .

There are very detailed inscriptions of Mentuhotep IV, which are considered to be the most important records of his short reign. They report a deployment of 10,000 men who were supposed to bring back a sarcophagus and lid. The expedition became famous for the "Gazelle Miracle", in which a fleeing gazelle exhausted itself and gave birth to its young on the exact block that was intended for the king. Another miracle of the expedition was the so-called "Brunnenwunder" (or "Regenwunder"), in which a rare sudden flood of rain revealed a well with clean water. The leader of the expedition was the vizier Amenemhet , who probably later ascended the throne as Amenemhet I.

Under Sesostris I there was another expedition in which 17,000 men were sent to break stones for sixty sphinxes and 150 statues.

The kings Sobekhotep IV and Sobekemsaf I are attested from the Second Intermediate Period .

New kingdom

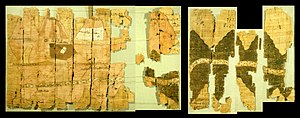

From the beginning of the New Kingdom up to the Ramesside period there are only names and titles of Ahmose I , Amenhotep II , Amenhotep IV , Sethos I , Ramses II and Sethos II. It is assumed that the famous Punt expedition of the Queen Hatshepsut took place further north through Wadi Gasus . The most obvious reference to Wadi Hammamat in the New Kingdom, the Turin deposits papyrus from the time of Ramses IV. Is It is a card that the way to the familiar. Bechen -Steinbrüchen, as well as the gold - and silver mines continue shows east.

Third intermediate and late period

Inscriptions from Shabaka , Amenirdis I , Taharqa , Psammetich I , Psammetich II , Necho II , Amasis , Cambyses II , Dareios I , Xerxes I and Artaxerxes I date from the Third Intermediate Period and the Late Period . The last hieroglyphic Inscriptions mention Nectanebo II from the 30th dynasty . Further recordings were made in demotic and can be found in the nearby Paneion .

Ptolemies

Under the Ptolemies , interest in the desert routes to the Red Sea and East Africa rose again and was partly driven by the increased need for war elephants , which were needed for clashes with the kings of the Seleucid Empire in Syria . The quarrying of stones was reduced, but the desert routes including the Wadi Hammamat and the Berenike routes were expanded and equipped with new wells or cisterns and way stations.

Roman time

The Roman rulers built on the Ptolemaic infrastructure and further expanded the desert trade. The fortified Hydreuma near Bir Hammamat , the well-preserved, partially rebuilt, circular fountain and visual signal towers on the mountain peaks along the Hammamat route belonged to the Roman road system . With the help of camel caravans , large research vessels, and recently acquired knowledge of monsoons , they sailed to Africa , possibly as far as Dar-es-Salaam , Aden and the Spice Coast , on a regular basis.

The extraction of bechen stone was no longer very intensive in Roman times , but breccia verde antica was mined all the more frequently , as can be seen in large, roughly hewn, but abandoned blocks. However, a carefully built temple with a few side rooms was built near the bechen quarries, which, thanks to an inscribed naos , could be dated to the time of Tiberius . There were also graffiti records by Augustus , Nero , Titus , Domitian , Antonius, Maximus and perhaps Hadrian .

At the end of the second century, the records became increasingly sparse, presumably because of many internal difficulties arose in the Roman Empire. The costly and distant trade in the Red Sea and the desert routes were difficult to maintain. The quarries were abandoned, as were the associated houses, temples and shrines.

Byzantine and Middle Ages

In the Byzantine period , some cities and fortresses were built at Abu Sha'ar , Berenike and Bir Umm Fawakhir. The medieval trade and pilgrimage routes leading either north through Wadi Qina or through Wadi Qash in the south. In the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries, the Mamelukes built a port at Quseir al-Qadim.

literature

- André Bernand: De Koptos à Kosseir. Brill, Leiden 1972.

- J. Couyat, P. Montet : Les Inscriptions hiéroglyphiques et hiératiques du Ouadi Hammamat. L'Institut Français d'Archeologie Orientale, Cairo 1912 ( Mémoires publiés par les membres de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire 34), online .

- Georges Goyon: Nouvelles Inscriptions Rupestres du Wadi Hammamat. Maisonneuve, Paris 1957.

- Rolf Gundlach : Wadi Hammamat. In: Wolfgang Helck , Eberhard Otto : Lexicon of Egyptology. Edited by Wolfgang Helck and Wolfhart Westendorf . Volume 6: Stele - Cypress. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1986, ISBN 3-447-02663-4 , pp. 1099-1113.

- Rainer Hannig : Large concise dictionary of Egyptian-German. (2800-950 BC) . von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9 , p. 1161.

- Thomas Hikade: Expeditions to the Wadi Hammamat during the New Kingdom. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology. 92, 2006, ISSN 0075-4234 , pp. 153-168.

- Carol Meyer: Wadi Hammamat. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London et al. 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 868-871.

- G. Posener : La première domination Perse en Égypte. Recueil d'inscriptions hiéroglyphiques. Institut française d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1936 (= Bibliothèque d'Étude. Vol. 11, Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, ISSN 0259-3823 ).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Carol Meyer: Wadi Hammamat. In: Bard: Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. 1999, pp. 868-869.

- ↑ a b c d e f Carol Meyer: Wadi Hammamat. In: Bard: Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. 1999, p. 869.

- ↑ a b c d e Carol Meyer: Wadi Hammamat. In: Bard: Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. 1999, p. 870.

- ↑ Demotic Graffiti from the Wadi Hammamat (English).

- ^ Carol Meyer: Wadi Hammamat. In: Bard: Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. 1999, p. 870., see also: Indo-Roman trade and relations .

Coordinates: 25 ° 57 ′ 51.9 ″ N , 33 ° 30 ′ 14.6 ″ E