African ostrich

| African ostrich | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pair of ostriches at Cape Point |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Struthio camelus | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

The African ostrich ( Struthio camelus ) is a species of bird in the ostrich family and is the largest living bird on earth after the closely related Somali ostrich . While only in today Africa of the south Sahara is home, he was based in former times also in West Asia. The ostrich has always been of interest to humans because of its feathers , its flesh and its leather, which led to the extinction of the bird in many regions.

features

The males of the ostrich are up to 250 centimeters high and weigh up to 135 kilograms. Females are smaller: they are 175 to 190 centimeters high and 90 to 110 kilograms in weight. The males, called roosters, have black plumage. The feathers of the wings and the tail are white. The females, called hens, on the other hand, have earth-brown plumage ; Their wings and tail are lighter and have a whitish-gray color. The youth dress resembles the appearance of the female, without the characteristic separation of wings and tail. Newly hatched chicks, on the other hand, are fawn-brown and their downy dress has dark spots. The down of the back plumage is set up like a hedgehog bristly. The bare legs and the neck are gray, gray-blue or pink, depending on the subspecies. In the male, the skin glows particularly intensely during the breeding season.

The ostrich has a long, mostly bare neck. The head is small in relation to the body. The eyes are of a diameter of 5 centimeters, the largest of all land vertebrates. The pool of ostriches is anteriorly by the symphysis pubis ( pubic symphysis closed). This is only the case with ostrich-like birds. It is formed by the three clasp-like pelvic bones ( iliac bone , ischium , pubic bone ), between which there are large openings that are closed by connective tissue and muscles . The ostrich has very long legs with strong running muscles. Its top speed is around 70 km / h; The ostrich can hold a speed of 50 km / h for about half an hour. In order to adapt to the high running speed, the foot , unique in birds, has only two toes ( didactyly ). The legs can also be used as effective weapons: both toes have claws , of which the one on the larger, inner toe is up to 10 cm long.

skeleton

The sternum is not wearing a sternum crest as with all ostrich-like. This makes it look flat and flat like a raft (Latin: Ratis ), which is why this group of birds is also known as Ratites . Like all birds, the ostrich has a full shoulder girdle . A special feature is the strong fusion of the raven bone ( os coracoideum ) and collarbone ( clavicula ), between which only an oval hole remains open. The wings are quite large for ratites, but like all ratites not suitable for flying . The own weight of an ostrich is far more than what it would allow a bird to soar into the air. Instead, the wings are used for courtship , shade, and balance while running fast. The ostrich is the only recent bird to have claws on all three fingers .

voice

One of the most typical vocalizations of the ostrich is a call from the male that resembles the roar of a lion . A deep “bu bu buuuuu huuu” is repeated several times. The sound is emitted during courtship and when disputes over rank are held. In addition, ostriches of both sexes are able to whistle, snort and growl. Only young ostrich chicks give more melodic calls, which are used to attract the mother's attention.

distribution and habitat

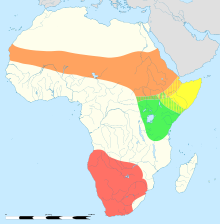

The natural distribution area of the ostrich is Africa , especially East and South Africa . It became extinct on the Arabian Peninsula , in Western Asia and in Africa north of the Sahara.

Ostriches live in open landscapes such as savannahs and deserts . They prefer habitats with short grass and not too tall trees; where the grass grows higher than a meter, ostriches are absent. Occasionally they advance into the scrubland, but do not stay there long because they are prevented from moving quickly and cannot see far there. Pure deserts without vegetation are not suitable as permanent habitat, but are crossed on hikes. Because ostriches get all of their hydration needs from food, they do not need access to water and long dry spells are not a problem for them either.

African ostriches were first introduced to Australia in 1869, with further imports following in the 1880s. With the imported ostriches, farms were to be built in Australia to supply the fashion industry with feathers. Already before the turn of the century there were overgrown ostriches, the settlement of which was specifically promoted on some farms. In 1890 there were 626 ostriches near Port Augusta and the city of Meningie , in 1912 the number was 1,345 individuals. After the demand for ostrich feathers collapsed after the end of World War I , there were further releases, but the number of ostriches released is unknown. In the Australian state of Western Australia , ostriches could not establish themselves in the wild, in New South Wales these ostriches reproduced in the regions in which they were released into the wild in the first years, the population then remained stable for some time and then steadily decreased. In many regions where ostriches lived for several years, they disappeared again by the middle of the 20th century. North of Port Augusta there were still 150 to 200 ostriches in the 1970s. Most of these birds died during the prolonged drought from 1980 to 1982. After 1982 only 25 to 30 ostriches were counted there.

Way of life

Ostriches are diurnal birds that are particularly active in the twilight hours. At times when food is scarce, they have to undertake long hikes and are able to hike in the midday sun. They rest at night, usually with their necks erect and eyes closed. Only for short, deep sleep phases, the neck and head are placed on the back plumage or on the floor.

Outside the breeding season, ostriches usually live in loose associations, which can include two to five, but in some areas a hundred or more animals. In desert areas, up to 680 animals gather around water holes. The cohesion of the ostrich associations is loose, because the members of the group come and go as they please. Often you can also see individual ostriches. Nevertheless, there are clear hierarchies within the groups. Disputes over rank are mostly regulated by threatening sounds and threatening gestures ; wings and tail feathers are raised and the neck is held upright. The lower-ranking bird shows its submission by bending its neck into a U-shape and holding its head down; wings and tail also point downwards. A dispute over rank can rarely lead to a short fight.

At the time of reproduction, the loose associations dissolve and sexually mature males begin gathering a harem .

nutrition

Ostriches are primarily herbivores , but occasionally also eat insects and other small animals. They mainly eat grains, grasses, herbs, leaves, flowers and fruits. Insects, like caterpillars and grasshoppers, are only complementary foods. Preference is given to food that can be picked from the ground. Only in exceptional cases are leaves or fruits read from bushes or trees. Ostriches can use their food optimally, which is ensured by a 14 meter long intestine . The gizzard can absorb up to 1300 grams of food. To help break up food, ostriches swallow sand and stones ( gastroliths ) and have a tendency to pick up all sorts of small objects that might serve similar purposes. Coins, nails and similar objects have therefore already been found in ostrich stomachs. Materials swallowed as a digestive aid can make up up to 45 percent of the gizzard content.

Enemies

The main enemies of the ostrich are lions and leopards . As ostriches usually stay in groups, they protect themselves from the danger by observing them together. This reduces the risk of the individual bird being chosen as prey; in addition, each group member has more time to eat. In the savannahs, ostriches often join herds of zebras and gazelles as these animals are vigilant on the lookout for the same predators.

"Head in the sand"

An old saying goes that when threatened by enemies, the ostrich "bears its head in the sand". In fact, the ostrich, which can run very quickly, usually saves itself by running away. But he is also able to defend himself with a targeted kick that can kill a lion or a person. However, brooding ostriches in particular often lie on the ground when danger is approaching, keeping their neck and head straight. Since the neck lying flat on the ground can no longer be seen from a distance, this behavior could have led to the legend. It is also conceivable that when observing ostriches from a distance, one succumbs to an optical illusion due to the shimmering air over the hot steppe floor. With this effect, the head of grazing ostriches optically "disappears" for the distant observer.

Reproduction

Territory, courtship, copulation and clutch

The mating season is very different in different regions of Africa. In the savannahs of Africa it falls in the dry season between June and October. In drier areas, for example in the Namib desert , the breeding season lasts all year round. The roosters become territorial during the mating season. You then defend an area between 2 and 15 square kilometers. The size of the area depends on the food supply. The more fertile the area in which the district is located, the smaller it is. The area defense includes calls indicating the area and patrolling the area. Other males are driven out of the territory by the territorial rooster with threatening gestures, but females are received with a courtship ritual. Although there are also monogamous couples, a rooster usually has an entire harem. One of the females can be clearly identified as the main hen. It often stays with the rooster for several years and, like the territorial rooster, has its own territory, up to 26 square kilometers in size. In addition, there are several mostly quite young, low-ranking females, the so-called side hens.

Ostriches have a penis that is everted for copulation, but is also always visible when the cock relieves itself. Because the penis, which usually rests in the channel of the cloaca, is disturbing . Many bird species only press the cloacal openings together when mating; but ducks, geese and also the ostrich relatives have an evertable penis.

The rooster mates first with the main hen, then with the side hens. The pairing is preceded by a courtship ritual in which the rooster presents its wings and swings them up and down alternately. At the same time, it inflates its colored neck and also lets it swing alternately to the left and right. In this position, the rooster walks towards the hen with his feet stamping. The female shows her willingness to mate with a "gesture of humility" in which she lets her head and wings hang down. After mating, the main hen chooses one of the nest pits that the rooster has previously created. These are hollows about three meters in diameter, scratched into the ground with their feet. The side hens lay their eggs in the same nest and are driven away by the main hen after they have been laid. Often afterwards they go to the territory of another ostrich, with which they also mate.

The main hen lays an average of eight, rarely up to twelve eggs. In addition, there are two to five eggs per neighbor hen. In the large community nests there are up to 80 eggs at the end. The eggs are shiny white, weigh up to 1,900 grams and have a diameter of 15 centimeters, and their content corresponds to that of 24 chicken eggs. The egg shell is 2 to 3 mm thick. This makes them one of the largest eggs in the world in absolute terms, but they are the smallest in relation to the size of the adult animal. The unfertilized egg initially consists of a single cell .

Brood care and rearing of the young birds

Only the actual pair ultimately remains on the nest and jointly takes care of the brood. Since a bird can only cover a maximum of 20 eggs with its body, the main hen removes the excess eggs from the co-hens that have since been driven out. In the middle of the nest, their own eggs are placed, which the main hen obviously recognizes by size and weight. So although own eggs are preferred, there is still room for ten to fifteen eggs from side hens that are also hatched. But not only the co-hens benefit from this behavior: If the clutch is attacked by egg robbers, the outer eggs of the co-hens are more likely to be affected, which also protects the eggs of the main hen. Usually the eggs are incubated by the hen during the day and by the rooster at night. Numerous predators, especially jackals , hyenas and Egyptian vultures , try again and again to lure the breeding birds away from the nest in order to get to the eggs. Only ten percent of all clutches are hatched successfully.

The chicks hatch after six weeks. They are already wearing a light brown down dress and are fleeing from the nest. The parent birds continue to care for the brood by spreading their wings over the young to protect them from sun and rain. The chicks leave the nest for the first time when they are only three days old and follow their parents everywhere. Occasionally two pairs of ostriches meet. This leads to threatening gestures and often to fights, in which a couple is victorious and then the boys of the losing couple take over. In this way, a strong couple can gather a number of young from other couples around them. In one case, an ostrich pair with 380 chicks was observed. This behavior, like the hatching of the eggs of the co-hens, in turn means that in the event of an attack by predators, it is more likely that the chicks are strangers and not your own. Even so, only around 15 percent of chicks complete their first year of life.

At the age of three months, the boys switch from down to youth clothing. After a year they are as big as the parent birds. Female ostriches reach sexual maturity at the age of two. Male ostriches already wear the plumage of adult roosters when they are two years old. However, they are only able to reproduce when they are three to four years old. African ostriches have a life expectancy of around 30 to 40 years; in zoos they can live to be over 50 years old.

Tribal history and systematics

The African ostrich is the only living species of the ostrich (Struthionidae), of which only fossil species are otherwise known. Which other family of ratites can be identified as sister groups of the ostrich is controversial. The recently extinct elephant birds of Madagascar and the rhea are discussed ; in the latter, many zoologists are convinced that they have acquired their similarity to the ostrich in convergent evolution . A recently re-discussed hypothesis sees the ostrich's sister group as a common taxon of rheas and cockroaches . Often the ostrich is classified as a basal taxon at the root of ratites; There are, however, numerous other approaches (see ratites for details ).

Five subspecies are usually distinguished:

- The North African ostrich ( Struthio camelus camelus ) lives in the savannahs of West Africa and is distributed across the Sahel region to western Ethiopia ; north of the Sahara it is extinct.

- The Somali ostrich ( Struthio molybdophanes ) colonizes Somalia and eastern Ethiopia and is now mostly regarded as a separate species since 2014.

- The Maasai ostrich ( Struthio camelus massaicus ) lives in Kenya and Tanzania .

- The South African ostrich ( Struthio camelus australis ), on the other hand, is found in southern Africa.

- The now extinct Arabian ostrich ( Struthio camelus syriacus ) once lived in Western Asia.

- First knowledge about the occurrence of ostriches in India goes back to the 1880s. Back then, bones were found in the Siwaliks on the southern slopes of the Himalayas . In 1958, Dr. Sali the first eggshells. The British Museum in London has confirmed the accuracy of the find.

- For some years now, fragments of ostrich eggshells from China have also been identified. Further north there are images of ostriches in the rock art of Inner Mongolia. As a result of the change from a dry climate to a humid monsoon climate at the end of the Ice Age, the Asian ostriches lost their livelihood.

Populations of the Western Sahara have sometimes been separated as the sixth subspecies called the dwarf ostrich ( Struthio camelus spatzi ). They are smaller on average, and their eggshells have a different structure. This subspecies is largely rejected by experts. The separation of the Somali ostrich as an independent species ( Struthio molybdophanes ) , which is occasionally carried out on the basis of DNA analyzes, is also questioned ( see above )

The main differences between the individual subspecies are the colors of the skin areas of the cocks' neck and legs. The hens of the subspecies, on the other hand, can hardly be distinguished from one another. The neck and legs of the North African ostrich, the Masai ostrich and the South African ostrich are pink, and the Somali ostrich blue-gray. The intensity of the pink shade is different for each subspecies. The North African ostrich also has a neck ring made of white feathers, which is somewhat less pronounced in the Maasai ostrich; it is absent in the Somali ostrich and the South African ostrich.

Fossil history

The origin of the ostrich family has not yet been clarified. Some experts consider the genus Palaeotis to be the oldest representative , whose fossils from the Middle Eocene were found in the Messel pit and in the Geiseltal . According to other editors, however, these representatives of larger ratites show more similarities with the rheas and could be classified as their sister group. According to recent studies, however, Palaeotis is at the base of the development of the ratites and is therefore a distant ancestor of the African ostrich.

Birds, which undoubtedly belong to the ostrich, have been documented since the Miocene . This makes Struthio a very old genus of birds. Struthio orlovi from the Miocene of Moldova is the oldest known species. During the Pliocene , several species lived in Asia, for example in Mongolia and in East Asia ( Struthio chersonensis , Struthio mongolicus , Struthio wimani ). The Asian ostrich ( Struthio asiaticus ) lived in the Pleistocene in the steppes of Central Asia. The African ostrich, which lives today, appeared in the Pleistocene, and its distribution area also included Spain and India during the last Ice Age . At the Dmanissi site , where the oldest human fossils were found outside of Africa, a thighbone of the giant ostrich ( Struthio dmanisensis ) was discovered in 1983 and 2012 .

History, mythological and magical aspects

In the so-called Apollo 11 cave in Namibia , archaeologists found artificial pearls made from ostrich egg, which date from the ninth millennium BC. During archaeological excavations in Caspia , engraved ostrich eggs were found, which are one of the first artifacts of this time. There are also fragments of decorated ostrich eggs from the Epipalaeolithic in the northern Sahara . These are adorned with geometric patterns, as they also give naturalistic representations of nature. On these, as well as on stone plaques from the same period, ostriches are depicted, among other things. In India over 40 sites with fragments of ostrich eggshells have been discovered. They are located in the western and central states of Uttar Pradesh, Maharastra, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. Radiocarbon studies show that some were engraved 25,000 to 40,000 years ago. A stone industry of the Upper Paleolithic (Paleolithic) was found together with the eggshells.

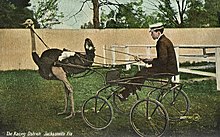

In ancient Egypt , ostriches were important breeding and hunting animals, which were of great importance as suppliers of eggs, meat and feathers. The hunt for ostriches was a special social pleasure until the New Kingdom . The large, white decorative feathers were considered to be a symbol of light and justice due to their even and symmetrical cilia and elegant shape and adorned royal standards and pompous fronds. From ancient Greece and Syria, ostriches are documented as draft animals and even as mounts.

Ostrich eggs served as grave decorations with a cultic function: The oldest finds come from the ancient Egyptian city of Abydos and are around 1800 BC. Dated BC, Punic graves near Carthage and graves in Fessan were also decorated with ostrich eggs. In 1771 ostrich eggs on a Muslim grave near Palmyra were reported. In Europe, ostrich eggs were found as grave goods in Mycenae and several times in ancient times in Italy.

In many regions of Black Africa ostriches have found their way into rituals, fairy tales and fables. The eggs have a practical use for the Khoisan , who use them as drinking vessels or make collars and bracelets from the shells.

On the Arabian Peninsula , archaeologists found painted ostrich egg shells from the 2nd and 1st millennium BC in numerous places. That were used as containers. There was probably a ban on hunting the birds in areas where they were considered deities. In contrast to ancient Mesopotamia , their meat was obviously not eaten. In the Islamic period, the eggshells were used as oil lamps, especially in mosques. Richard Francis Burton described them as a popular souvenir of Mecca pilgrims in the mid-19th century . The fact that there was a ban on breaking ostrich eggs during the pilgrimage can be interpreted as an indication of a certain veneration of the bird.

In the Islamic popular belief of North Africa , the magical aspect of the ostrich has been preserved in some places. Five ostrich eggshells (compare the number with Hamsa ) crown the minaret of Chinguetti in Mauritania.

Ostrich eggs, which are very often attached to the rooftops of Ethiopian Orthodox church buildings or hang over the doors to the chancel, are supposed to have the same protective function . Analogous to how the ostrich always guards its eggs, these now protect the house of God. Another reference to the ostrich refers to its role model function: just as the bird does not lose sight of its eggs buried in the sand, may the believer give God his undivided attention during prayer.

In the Christian European Middle Ages, the same picture could be interpreted in the opposite way, in that the ostrich forgets its buried eggs and thus becomes a sinner who neglects his duties to God. The ostrich that sticks its head in the sand is also a proverbial negative idea.

In Christianity, like the unicorn , the ostrich was a symbol of virginity. Concepts of the Physiologus from the 2nd century AD were taken up, according to which the bird allows its eggs to hatch in the sun or only needs to look at the eggs so that they are hatched. From the 16th century the bouquet became one of the attributes of justice ( Iustitia ). Magnificent, richly decorated drinking vessels and cups were made from the shells of ostrich eggs.

In Iran , the ostrich, Persian shotor-morgh ( shotor "camel", morgh "bird"), is a symbol of a slacker: if you ask him to fly, he claims to be a camel, but if you want to load him up, he gives to be a bird. Hence the Persian proverb: Either be a bird and fly, or be a camel and carry! that means “make up your mind” or “take responsibility!”.

use

When ostrich feathers became fashionable as hat ornaments for the wealthy European ladies in the 18th century, the hunt for birds began to take on such proportions that it threatened the existence of the species. In West Asia, North Africa and South Africa the ostrich was completely wiped out. In the 19th century, ostriches began to be farmed as wild ostriches had become extremely rare. The first of these farms was established in South Africa in 1838. In the second half of the 20th century, more and more ostrich farms were opened in Europe and North America. Ostrich farming has been booming in parts of South America for several years. In Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia in particular, farms are seen as a lucrative alternative source of income.

Today the feathers hardly play a role in ostrich farming. Ostriches are now primarily bred for their meat and the gray-blue skin from which leather is made. The meat of the ostrich has its very own taste, which can best be compared to beef or that of bison . Lampshades and ornaments are made from the shells of the eggs.

In South Africa (world market share: 75%) 45% of the income from ostrich farming is generated from meat and skin, 10% from feathers. In Europe, meat is 75% and skin is 25%.

As riding and draft animals , ostriches have only recently been used as a tourist attraction. However, this has no cultural tradition anywhere.

Dealing with ostriches is not without its dangers. The roosters in particular are aggressive during the breeding season. Intruders are kicked. The force and especially the sharp claws can lead to serious injuries or even death.

The Arabian ostrich was eradicated at the beginning of the 20th century. This subspecies was quite common in Palestine and Syria up until World War I, but was then destroyed by motorized hunts with firearms. The last wild animal died in Jordan in 1966 . In 1973, ostriches were released in the Negev desert in Israel , which means that they are now home there again. However, it is a North African ostrich, another subspecies.

The species as a whole is not endangered as it is still common, especially in East Africa. Regionally, however, the ostrich is rare, for example in West Africa.

etymology

The word ostrich comes from the ancient Greek strouthiōn (στρουθίον), which means something like 'big sparrow'. The Greeks also referred to the ostrich as' camel sparrow '(στρουθοκάμηλος strouthokamēlos ), which explains the species' scientific name, Struthio camelus .

It is noticeable that the bouquet bears the clarifying addition of bird in various languages . The Dutch struisvogel and the Swedish fågeln struts correspond to the German ostrich . The English name ostrich, the French autruche and the Portuguese and Spanish avestruz all go back equally to the Latin avis struthio - avis also means nothing other than 'bird'.

literature

- Josep del Hoyo : Ostrich to Ducks. Lynx, Barcelona 1992, ISBN 84-87334-10-5 ( Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 1.)

- Stephen J. Davies: Ratites and Tinamous. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-19-854996-2 .

- Egon Friedell : Cultural history of Egypt and the ancient Orient. Beck, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-58465-7 .

- Caesar Rudolf Boettger : The domestic animals of Africa. Your origin, importance and prospects for the further economic development of the continent. Fischer, Michigan 1958.

- Burchard Brentjes: The becoming a pet in the Orient - An archaeological contribution to zoology . Ziemsen, Trier 1965

Web links

- Struthio camelus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on December 18 of 2008.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings for Struthio camelus in the Internet Bird Collection

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Christopher M. Perrins (Ed.): The BLV encyclopedia birds of the world. Translated from the English by Einhard Bezzel. BLV, Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-405-16682-9 , p. 35 (title of the original English edition: The New Encyclopedia Of Birds. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2003).

- ↑ 1: pubic bone 2: ischium 3: iliac bone 4: symphysis 5: synsacrum 6: renal pits 7: femur 8: pygostyle

- ↑ 1: Sternum 2: Ravenbone 3: Clavicle 4: Shoulder blade 5: Upper arm 6: Ribs 7: Thigh 8: Shin 9: Fibula

- ↑ a b P. J. Higgins (Ed.): Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 1, Ratites to Ducks, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1990, ISBN 0-19-553068-3 , p. 68.

- ^ PJ Higgins (Ed.): Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 1, Ratites to Ducks, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1990, ISBN 0-19-553068-3 , p. 69.

- ↑ a b Elke Brüser: astonishment at the bouquet. In: www.fluegelschlag-birding.de. Elke Brüser, accessed on February 19, 2020 .

- ↑ Christopher Perrins (ed.): BLV encyclopedia birds. BLV, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-405-16682-9 , p. 36.

- ↑ G. Kreutzer: Ostrich egg shells with engravings in India. In: Hagengerg prehistoric times; Hornberg issue 2/1989, ISSN 0170-5725 p. 16.

- ↑ Peter Houde, Hartmut Haubold: Palaeotis weigelti restudied: a small Middle Eocene ostrich (Aves: Struthioniformes). In: Palaeovertebrata. Volume 17, 1987, pp. 27-42.

- ↑ Dieter Stefan Peters: A complete skeleton of Palaeotis weigelti (Aves, Palaeognathae). In: Courier Research Institute Senckenberg. Volume 107, 1988, pp. 223-233.

- ↑ Gareth J. Dyke, Marcel van Tuinen: The evolutionary radiation of modern birds (Neornithes): reconciling molecules, morphology and the fossil record. In: Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. Volume 141, 2004, pp. 153-177.

- ↑ Abesalom Vekua: Giant Ostrich in Dmanisi Fauna. In: Bulletin of the Georgian National Academy of Sciences 7, 2013, pp. 143-148 ( online , PDF).

- ^ JD Fage et al .: The Cambridge history of Africa Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press 1982, ISBN 0-521-22215-X , p. 457.

- ^ JD Fage et al .: The Cambridge history of Africa Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press 1982, ISBN 0-521-22215-X , p. 398.

- ^ JD Fage et al .: The Cambridge history of Africa Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press 1982, ISBN 0-521-22215-X , p. 608.

- ↑ Egon Friedell: Cultural history of Egypt and the ancient Orient. Pp. 135, 228.

- ↑ Caesar Rudolf Boettger: The domestic animals of Africa. P. 153 f.

- ↑ Burchard Brentjes: The pet development in the Orient. P. 77.

- ↑ Ernst Schüz: The egg of the ostrich (Struthio camelus) as a utility and cult object. In: Tribus No. 19, Lindenmuseum Stuttgart, November 1970, pp. 79–90, here pp. 82 f.

- ^ DT Potts: Ostrich distribution and exploitation in the Arabian Peninsula. Antiquity, Volume 75, No. 287, 2001, pp. 182–190 ( Memento from November 29, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 2.1 MB)

- ^ Wolfgang Creyaufmüller: Nomad culture in the Western Sahara. The material culture of the Moors, their handicraft techniques and basic ornamental structures. Burgfried-Verlag, Hallein (Austria) 1983, p. 457.

- ^ Geoffrey Wainwright, Karen Westerfield Tucker: The Oxford History of Christian Worship. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, ISBN 978-0-19-513886-3 , p. 136.

- ↑ Gerd Heinz-Mohr: Lexicon of symbols. Images and signs of Christian art. Herder, Freiburg a. a. 1991, ISBN 3-451-04008-5 , p. 302.

- ^ Wilhelm Molsdorf: Christian symbolism of medieval art. Karl W. Hiersemann, Leipzig 1926, pp. 141, 217.

- ^ The Green Vault Dresden : Ostriches as drinking vessels by Elias Geyer (before 1610), Staußeneipokale German, South German (around 1600) .

- ^ Republic of South Africa, Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries: A Profile of the South African Ostrich Market Value Chain