Ostriches (genus)

| Ostriches | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

African ostrich ( Struthio camelus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the order | ||||||||||||

| Struthioniformes | ||||||||||||

| Latham , 1790 | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the family | ||||||||||||

| Struthionidae | ||||||||||||

| Vigors , 1825 | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the genus | ||||||||||||

| Struthio | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

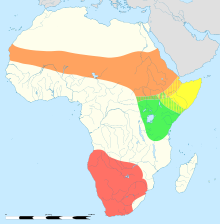

The ostriches ( Struthio ) are a genus of large, flightless birds found in relatively arid areas in Africa. It includes two recent species, the African ostrich ( Struthio camelus ) and the Somali ostrich ( Struthio molybdophanes ). In addition, there are a number of fossil and subfossil finds from Asia and Europe that are assigned to the genus.

features

The males of the ostrich are up to 275 centimeters high and weigh up to 156 kilograms. Females are smaller: they are 175 to 190 centimeters high and 90 to 110 kilograms in weight. This makes ostriches the largest birds in the world. They have an oval, horizontally aligned, heavy trunk and long, featherless legs with two forward-facing, thick toes on the feet. The head is small and feathered, the neck long and only minimally feathered. The eyes are relatively large; the beak is short, flat and broad. The plumage of the males is mostly black, that of the females is gray-brown.

Way of life

Ostriches are found in steppes, savannahs, open, dry forests and semi-deserts in Africa. They are omnivores, but prefer green plants. Small plants are pulled out of the ground and eaten along with their roots. Ostriches spend a large part of the day foraging for food and obtain a large part of the moisture they need from their food.

Reproduction

Ostriches are polygamous . Both males and females mate with multiple sexual partners. As a “nest”, the male scratches a recess in the ground in which several (up to 18) females lay their eggs. First, the main female usually lays seven to ten eggs in the nest, then several secondary females lay further eggs, so that the entire clutch size can comprise 20 to 25 eggs. A location is chosen as the location of the nest, which gives the brooding ostrich a good overview of the surroundings. Both the male and the main female incubate the clutch over a period of about six weeks. Three days after hatching, the young ostriches leave the nest and are then led and protected by the male and the main female. They are self-employed when they are around one year old.

species

- † Asiatic ostrich ( Struthio asiaticus )

- † Struthio brachydactylus

-

African ostrich ( Struthio camelus )

- † Arabian ostrich ( Struthio camelus syriacus )

- † Struthio coppensi

- † Struthio karatheodoris

- Somali bouquet ( Struthio molybdophanes )

- † Struthio novorossicus

- † Struthio orlovi

Individual bone finds of an extinct giant flightless bird from the old Pleistocene site of Dmanissi in Georgia were originally also assigned to the ostriches and carried under the scientific name Struthio dmanisensis . A 2019 study referred the species to the possibly related genus Pachystruthio . Palaeotis turn, one from the Geisel and the Messel Pit occupied flightless bird of the Middle Eocene , long considered the ostrich was closely connected and thus was within the family of Struthonidae. Here he formed his own subfamily of the Palaeotidinae. More recent revisions see these now as an independent family of the Palaeotididae. Depending on the view this is as a sister group of rheas ( Rheidae considered) or as Schwestertaxon all other ratites.

swell

- ↑ a b Sonal Jain, Niraj Rai, Giriraj Kumar, Parul Aggarwal Pruthi, Kumarasamy Thangaraj, Sunil Bajpai, Vikas Pruthi: Ancient DNA Reveals Late Pleistocene Existence of Ostriches in Indian Sub-Continent. In: PLoS ONE Volume 12 (3), 2017, p. E0164823, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0164823 .

- ↑ a b c David W. Winkler, Shawn M. Billerman, Irby J. Lovette: Bird Families of the World: A Guide to the Spectacular Diversity of Birds. Lynx Edicions (2015), ISBN 978-8494189203 . Page 36.

- ↑ Zlatozar Boev, Nikolai Spassov: First record of ostriches (Aves, Struthioniformes, Struthionidae) from the late Miocene of Bulgaria with taxonomic and zoogeographic discussion. In: Geodiversitas. Volume 31 (3), 2009, pp. 493-507.

- ↑ Nikita V. Zelenkov, Alexander V. Lavrov, Dmitry B. Startsev, Innessa A. Vislobokova, Alexey V. Lopatin: A giant early Pleistocene bird from eastern Europe: unexpected component of terrestrial faunas at the time of early Homo arrival. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology , 2019, p. E1605521, doi: 10.1080 / 02724634.2019.1605521 .

- ↑ Peter Houde, Hartmut Haubold: Palaeotis weigelti restudied: a small Middle Eocene ostrich (Aves: Struthioniformes). In: Palaeovertebrata. Volume 17, 1987, pp. 27-42.

- ↑ Dieter Stefan Peters: A complete skeleton of Palaeotis weigelti (Aves, Palaeognathae). In: Courier Research Institute Senckenberg Volume 107, 1988, pp. 223-233.

- ↑ Gareth J. Dyke, Marcel van Tuinen: The evolutionary radiation of modern birds (Neornithes): reconciling molecules, morphology and the fossil record. In: Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society Volume 141, 2004, pp. 153-177.

- ↑ Gerald Mayr: Hindlimb morphology of Palaeotissuggests palaeognathous affinities of the Geranoididae and other “crane-like” birds from the Eocene of the Northern Hemisphere. In: Acta Palaeontologica Polonica Volume 64 (4), 2019, pp. 669-678, doi: 10.4202 / app.00650.2019 .